Introduction

“The art of reframing is to maintain the conflict in all its richness but to help people look at it in a more open-minded and hopeful way” – Bernard Mayer in The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution, p.139

It is the normal tendency of the people to enter into processes of conflict resolution with their own interpretations of the problems. The interpretations relate to the background of the issues in dispute, the causes for the problems and the best ways to resolve the problems. The term ‘framing’ denotes how a party to the conflict or issue states the conflict or issue. While mediating a conflict, first the mediator allows the parties to state their perspectives of the issue that needs to be resolved. This step enables the mediator as well as the parties to perceive how each one is framing the conflict. In many of the instances, framing being the first viewpoint about the problem would bring out varied views of the dispute. For example, parties tend to use adversarial language in making the opening statements. Each party will point out the mistake of the other party and will state the negative points about the personal qualities of the opponents and require the compliance of the other party to meet their claims in entirety. Such conflicting framing of the parties would only lead to antagonism and would deter the parties from reaching an amicable and effective agreement to resolve the problem on hand.

What is Reframing?

“Framing refers to the way a conflict is described or a proposal is worded; reframing is the process of changing the way a thought is presented so that it maintains its fundamental meaning but is more likely to support resolution efforts.” To reframe a conflict means to change the way parties look at a conflict facilitating the emergence of behaviors that allow for the resumption or a significant change in the pace of negotiations. A successful reframing does not necessarily lead to the resolution of a conflict, but to a transformation of the relationship among parties from a phase of conflict to one of co-operation. Conflicts arise among other things from differences in disputants’ perceptions about the issue at hand, its importance and the actions that need to be taken. How the conflict is understood by the different parties depends strongly on the way the conflict is perceived, constructed and narrated, in other words on how it is framed.

Under normal circumstances, parties can perform the process of reframing on their own. However, the guidance of the process of reframing by a third party (a facilitator or mediator) would strengthen the process. In such cases, where a facilitator or mediator is involved in the process of reframing, it is the responsibility of the facilitator or mediator, to reframe the statements/accusations of the parties in such a way that the restatement of the issues less antagonism to each side to the conflict. In other words, it is the job of the mediator, to help the parties to communicate and redefine the ways, how the parties perceive the dispute. This is done, with the hope of establishing cooperation between the parties opposing each other. Therefore, the objective of reframing can be stated as to state the problem in the most acceptable way, so that both the parties to a dispute understand and look at the problem from the same angle and they accept the definition evolved, which leads to increase the potential for more collaboration among the parties to reach integrative and acceptable solutions.

It is possible that a process of reframing can take place quicker, if the parties to the dispute are receptive to the process. In case the parties are hostile to the process of reframing, it will involve more time to perform reframing. In many of the instances, the parties to the conflict lack the knowledge about the true nature of the conflict. The parties may realize that they are angry, that they were subjected to some wrong by each other, and that they want justice. However, they may not be in a position to identify the problem clearly and approach the resolution with an open mind. With the help of a mediator, and with the process of reframing, the parties get an opportunity to examine the true ideas behind the issue over a period. The process of reframing enables them to explore the causes that lead to the conflict. Once the parties are in a position to understand the problem from each other’s perspective, it implies that they would be able to arrive at solutions that work for the benefit of both the parties easily.

Techniques of Reframing

The scope of the problem, which is under review, determines the ways in which a mediator deals with the ways reframing proceeds. “Generally speaking, it is easier to help reframe interest disputes than reframing value conflicts over issues such as guilt, rights, or facts.” Nevertheless, in each case of dispute the objective is to develop a solution that is mutually acceptable based on the definition of the problem, which is understood by both the parties clearly, irrespective of the nature of the dispute. Therefore, it calls for the inclusion of all essential interests of both parties in reframing the interest-related issues. One of the most common ways the mediators to adopt in such cases is to move the issue based on whether the issue is general or specific. For instance, the mediator may enlarge the scope of issue by increasing the number of issues that need to be considered, instead of just revolving around the narrow conceptions of the issue, as seen and perceived by the parties. For accomplishing the expansion of the number of issues, the mediator would listen carefully to the explanations of the parties so that he can understand the basic interest relating to the assumed positions. “By shifting from specific interests, such as a pay increase, to more general interests such as overall employment benefits, mediators can help generate more feasible options for settlement.” Reframing value conflicts are more complicated and they are therefore difficult to accomplish. The reason for such difficulty is that in the value disputes, the parties become polarized. In such situations, the mediator has to apply certain specialized techniques for practicing reframing process. These tactics might help the mediator to make the issues more ripe and amenable to solution, when the disputants are holding different perspectives, which consider the values involved. The foremost technique the mediator adopts is to transform the values into interests. For example when there is a conflict based on the value of backwoods as opposed to values based on occupations, it would be difficult to decide the importance of both the elements. This issue needs to be resolved in favor of either of the parties, which involves deciding the relative importance of wilderness and job, as for some people the wilderness is important and for some other people, getting jobs becomes the priority. When a specific conflict is reframed taking into account the interest of both the groups as one group wants to retain the piece of land for preserving as backwoods, while the other group wants to develop the land for creating job opportunities. A feasible solution may be found by providing jobs serving people connected with the wilderness or by allowing the people to have the wilderness preserved in some other piece of land in return for the disputed piece of land. By trading off interests instead of values, it might become possible to reach long-lasting solutions to problems.

Identifying extendable “superordinate” goals, which would be accepted by the parties to a conflict, can be used as a strategy for dealing with value satisfaction in the process of reframing. For example on the abortion issue in the United States it may not possible to bring both the opposing sides in to an agreement on a value basis to decide whether getting aborted is within the moral standards. However, it may be possible to make both sides accept to the idea of helping women to avoid having unwanted pregnancies. Both sides may be made to work on programs for preventing undesirable childbirths and for providing other opportunities like adoption for women who still are confronted with the problem of unwanted pregnancy.

“People often explain their circumstances, emotions, and ideas through the use of metaphors, analogies, proverbs and other imagery.” Using new metaphors to describe existing situation is another technique used in reframing. Use of metaphors increases the possibility of the parties to the disputes to talk with each other freely and to have a better appreciation of the conflict. “Using metaphors that both parties relate to can help open up communication and increase understanding of the conflict and possibilities for resolution.” Avoidance is another technique normally employed for reframing. This technique implies that the mediator avoids either indentifying or responding to directly the differences in the values as possessed by the disputants. Alternatively, the mediator may reframe the differences to make the parties agree to disagree on certain points relating to the issue.

There are certain essential points that must be kept in mind while indulging in the reframing process. It must be remembered that the reframing process deals with “changing the verbal presentation of an idea, concern, proposal, or question so that the party’s essential interest is still expressed but unproductive language, emotion, position taking, and accusations are removed.” Therefore, it becomes vitally important that the mediator is careful and use appropriate language while reframing the issues. Based on the expertise and skill of the mediator, he should be able to restate the conflict in terms of an amount expressed in money or another medium of exchange that is thought to be a fair exchange for something and the expectations and claims of the parties. “The challenge is to convert polarizing language into neutral terms, removing bias and judgment, without diluting the intensity of the message or favouring either side.”Last but not the least is the nature of the parties to be explicit about the issues on which they stand divided. Only with the explicitness of the parties, the mediator would be able to reframe the problem in simpler and acceptable terms to reach an amicable settlement. The process of conflict resolution involves different phases of dialogues between the adversaries and the facilitator. In the cycle, once the adversaries have accustomed to the process of resolving the conflict, they will start talking more openly about expressing their sides on the problem. Finally, accepting the reframing of an issue depends on the time at which the resolution was attempted and the willingness of the parties to accept the redefined version of the problem. In this context, this study evaluates the conditions that allow for a successful use of reframing in conflict transformation. In order to lend a theoretical support to the discussion on the findings, the study undertakes the case study of Oslo accords entered into in dealing with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Problem Statement

There are a number of conflicts in the eastern and southern neighborhoods of the European Union and they remain unsettled despite negotiations conducted by top-level actors. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of nationalist movements in the new independent states were mainly responsible for the occurrence of these conflicts. Violence, large-scale population displacements and unsettled status are the repercussions of these conflicts. For example in the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, repeated attempts have been made to arrive at an amicable solution involving two states that might lead to the establishing a separate land for Palestine to exist alongside Israel. Government of Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) are the direct negotiating factors, while there are a number of other domestic and international actors involved in the conflict. Governments of United States, Russia, European Union and the United Nations are keen in arriving at a long-lasting solution to the satisfaction of both Israel and Palestine. Top-level actors have predominantly conducted various rounds of Negotiations and peace talks, with no possibility of reaching any tangible solution so far. In this context, this study explores the role of reframing in conflict resolution and the conditions that allow successful reframing in the conflict transformation. The findings of the study are expected to add to the existing knowledge on the reframing process and its impact on conflict transformation and the resultant resolution. To this extent, this study assumes significance.

Aims and Objectives

This thesis aims at exploring the potential and limits of reframing as a technique to approach a conflict and facilitate its resolution. Revolving around the central focus the study makes an in-depth study of the process of reframing, various techniques involved in the process and their relative characteristics and limitations. The study examines in detail the necessary conditions that need to be met for a successful transformation of the conflict if not a resolution. In order to lend theoretical support to the central aim, the study undertakes the case study of the conflict between Israel and Palestine and study the possibility of reframing the conflict with the intention to transform the conflict that might lead to an ultimate resolution of the conflict. Making few recommendations for future research in the area of conflict resolution also forms part of the agenda of the current research. In effect, this research seeks to analyze:

- What is the objective of reframing and how the process is performed?

- What are the techniques involved in reframing the issues in a conflict?

- What are the possible impediments that would prevent reframing from arriving at a solution for the conflict?

- What are the underlying conditions that would allow a successful reframing for conflict transformation?

Method

The study involves an exploratory research into the available resources and follows the research design of a qualitative case study to accomplish the research objectives. Based on the review of the relevant research, a theoretical framework covering the reframing process is evolved for a clear understanding of the process and the necessary conditions for allowing a successful conflict transformation.

This thesis attempts to address the basic question of how reframing of conflict can be undertaken, how the meaning of conflict may change and contribute to the transformation of the conflict. There are three analytical concepts, which constitute the core of the research problem. They are:

- meaning,

- reframing of conflict

- conflict transformation.

Meaning of the conflict forms the base of reframing and conflict transformation. The question that needs to be answered in respect of meaning of conflict is the ways in which conflict is interpreted and defined in the theory. The meaning of conflict also includes the ways in which a conflict is constructed in the interaction of the agent and structure relating to the conflict. It also deals with the ways in which the interaction between adversaries is conducted in a conflict. In the case of Israeli-Palestinian conflict among the Israeli and Palestinian political elites and the domestic and internationals structures of the conflict form the predominant frames of the conflict.

The transition from conflict to cooperation is the core focus of this thesis. Therefore, it considers the important question of how change and continuity in the conflict are understood in theory. The study also covers the ways in which the adversaries act to change the meaning of the conflict and the linkage of meaning of the conflict and negotiation, in which reframing has a major role to play. The scope of the study includes the context of domestic and international arenas in preceding, facilitating and influencing the negotiation process in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Conflict transformation is a process distinct from conflict resolution and conflict settlement. The process of conflict transformation includes strategies that are outcome-process and structure-oriented strategies. They are embedded with long-term peace building efforts. The aim of conflict transformation is to ensure that any direct, cultural and structural violence are settled completely. Even though conflict transformation differs from conflict settlement and conflict resolution, it includes many ides and strategies used in conflict resolution for resolving the conflict. The process of resolving conflict includes several strategies and interactions among the parties to a conflict. The thesis covers the problems concerning the interplay of actor, strategy, structure and transformation of the conflict. The study extends to the ways in which the negotiations are linked to transformation of the conflict. In respect of the case of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the study extends to the Israeli and Palestinian frames of negotiation as well as the ways in which the actions of the political actors influence the process of transformation.

Organization of the Thesis

The remainder of the thesis is structured to have different chapters, with chapter 2 presenting a review of the relevant literature on conflict resolution and the role of reframing process in conflict resolution. The objective of this chapter is to enrich the existing knowledge on the subject of study. Chapter 3 provides a brief outline of the research methodology used for conducting this study leading to chapter 4, which presents the case study of the “Oslo Accords”. This chapter also presents an analysis of the findings from the review of the literature and the case study. Chapter 5 presents the concluding remarks that summarize the salient findings of this study along with few recommendations for future research in this field.

Literature Review

Introduction

Conflict management denotes the process of control of disputes that have been in existence for a long-time and which is rooted deeply. Conflict is viewed as an inseparable consequence of differences in values and interests that may occur within and in between communities. Existing institutions, historical relationships and the distribution of power may give rise to violence and resulting conflicts. Skill of suitable intervening agents in the matter of achieving political settlement is the core of conflict management. The objective of conflict management is to try to offer many interventions, which will make the continuing dispute resulting in more benefits and less damages to all the parties concerned. Framing and reframing result from the interplay between structural conditions i.e. external objective political realities and the subjective interpretations that different political actors give of them. Conflict settlement, conflict resolution and conflict transformation are the three paths identified as part of conflict management. Study of conditions that allow reframing in conflict transformation requires a thorough understanding of these basic elements in conflict management.

Conflict Settlement, Conflict Resolution and Conflict Transformation

Conflict settlement includes all outcome-oriented strategies aimed at achieving sustainable win-win solutions. It also encompasses the process of putting an end to direct violence. However, these strategies are under no obligation to address the underlying causes of the conflict. Most of the conflict settlement researchers use the ideology of management to define conflict as a problem of the political order. It can also be defined as the problem of status quo. Incompatible interests and/or competition for scarce power resources always give rise to violent and protracted conflict. Most research in the conflict settlement approach concentrate on identifying third-party strategies, which help in the transformation of the zero-sum conflict with the objective of ending the violence and enabling some form of political arrangement. Conflict settlement measures may be coercive or non-coercive in nature and the focus on direct violence is mostly outcome-oriented. While coercive measures signify the involvement by a third party for a short term, non- coercive measures are applied with long-term objectives in view. All conflict settlement strategies are aimed to put an end to violent conflict through implementing ceasefires or cessation of hostilities and the actions may lead to a more permanent political agreement.

Therefore, conflict settlement strategies have the limited scope of success and peace, in which a sustained win-win situation is considered as success. Peace is often seen in negative terms with no long-term objective of positive peace set as target. In other words ending of violent objective is the goal of conflict settlement and not achieving an enduring peace. The keeping of recognized social norms irrespective of whether they are right or wrong, which is the central focus of conflict settlement is aimed resolving the conflict. Thus, conflict settlement does not deal with the underlying causes of a conflict. This leads to a situation that a certain conflict might be settled permanently; but the possibility of a similar or related conflict arising later because of the same underlying causes of the earlier conflict is not permanently ruled out.

It is important to understand the relationship between the two ideologies of conflict resolution and conflict transformation. There has always been tension in the way in which the authors compare these two phenomena. It has been a subject of dissention and debate, whether conflict resolution is an inclusive term that includes conflict transformation; or whether conflict transformation is a broad term that includes the process of conflict resolution or whether the two terms can be considered synonymous, related or they describe different things.

As against conflict settlement, strategies relating to conflict resolution cover all process-oriented activities aimed at addressing the underlying causes of direct, cultural and structural violence. It follows the practice of reframing the conflict as a shared problem with mutually acceptable solutions. Conflict resolution strategies are mostly process and relation-ship oriented hosting non-coercive and unofficial activities like facilitation and consultation. Normally conflict resolution involves the inclusion of more number of actors such as civil society organizations. While most of the conflict resolution strategies are of medium term nature, the process of sustaining or developing dialogue involves a short-term involvement. The objective of conflict resolution is to discover the deeper common interests and share needs. This objective is expected to be achieved through increased cooperation and improved communication and the strategies are expected to result in a successful outcome of conflict management. The outcome in this case is defined to include the meeting of minimum requirements of satisfaction of the needs of both the parties.

In contrast to the approach adopted by conflict settlement, conflict resolution process starts with defining protracted conflicts as the natural outcome of unsatisfied human needs. Conflict resolution is based on the belief that conflict arises because of the underlying needs of participants. There are varying needs such as “security, identity, recognition, food, shelter, safety, participation, distributive justice and development.” Deepening and broadening of the understanding of the conflict is the central focus of conflict resolution. Conflict resolution strives to achieve the understanding levels by concentrating on negotiable interests and adopt measures that can go beyond the conflict settlement strategies, which are merely outcome-oriented.

“To end or resolve a long-term conflict, a relatively stable solution that identifies and deals with the underlying sources of the conflict must be found.” Conflict resolution extends to areas beyond mere negotiation of interests to satisfy all the basic needs of the opponents. In the process of resolving the conflict, conflict resolution tries to respect the underlying values and identities associated with the conflict. Conflict resolution is based on an analytical and problem solving approach, which is not the case with conflict settlement. While the conflict settlement strategies aim at ending violence swiftly and in the process leaves the underlying factors untouched. Conflict resolution, on the other hand, includes strategies encompass social, political and economic changes that are aimed at implementing major reforms in the institutional structure of the society attempted in a more just and inclusive way.

Conflict transformation strategies are outcome-process and structure-oriented strategies embedded with long-term peace building efforts. The objective of conflict transformation is to overcome any direct, cultural and structural violence completely. Thus, conflict transformation differs from both conflict settlement and conflict resolution, although it is inclusive of many ides of conflict resolution. Conflict prevention is also an integral part of conflict transformation. Conflict prevention is “deducing from an adequate explanation of the phenomenon of conflict, including its human dimensions, not merely the conditions that create the environment of conflict and structural changes required to remove it, but more importantly the promotion of conditions that create cooperative relationship.” Therefore, unequal and suppressive socio-political structures can be considered as instrumental for the creation of protracted violent conflicts and it is essential that the marginalized groups are empowered to deal with the conflict effectively. The basic distinction between conflict resolution and transformation lies in their respective approaches. Conflict resolution approach lacks focus on dialogue and cooperation between actors having unequal status. It is a fact, that the necessity to fulfill ‘basic needs’ result in the generation of deep-rooted violence and hatred as the starting point. The focus of conflict resolution is to find solutions applicable during immediate and short-term basis and it sees conflict as a phenomenon that is bad and needs to be ended at the soonest. On the other hand, transformation approach keeps the after effects of the conflict completely in focus. Transformation approach recognizes conflict and tries to use in a positive to the advantage of the parties involved.

The work of Lederach is the foremost in the area of conflict transformation approach. He identified that there are three fundamental discrepancies or gaps of interdependence, justice and the process structure in the traditional framework of conflict. According to Lederach (1995) the goals of peacemaking under transformative approach are:

- Maintaining a broad conceptual idea of conflict and peace

- Promoting justice, reducing violence and restoring relationships

- Developing personal and systematic transformation opportunities

- Promoting a holistic view of the transformation process as restoration that covers justice, forgiveness and reconciliation

- Pursuing social empowerment

- Understanding the process more as a way of life rather than a technique and the outcome as a commitment to the truth and sustained restoration or relationships rather than agreements or results

Miall, Ramsbotham and Woodhouse define conflict transformation as a deepest level of conflict resolution. They acknowledge that other practitioners treat this term as one beyond the realm of conflict resolution , they have assigned the place for conflict transformation within conflict resolution. According to Miall et al transformation implies change and the change takes place in the deepest level of pattern that are responsible for the creation of violence in such things as institutions, relationships, structure and culture.

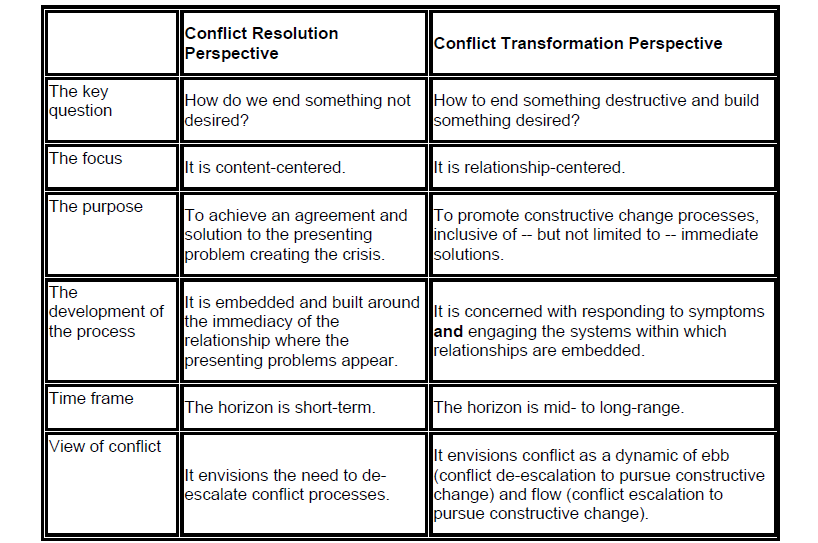

Table: Comparison of Resolution and Transformation Perspectives

The table above exhibits the difference between conflict resolution perspective and conflict transformation perspective.

Types of Conflict Transformation: According to Miall et al transformation happens in five different levels:

- context transformation,

- structural transformation,

- actor transformation,

- issue transformation

- personal and group transformation.

This list includes the various factors that affect the conflict. Aspects from a broad range of social, regional and international backgrounds constitute the context of conflict. According to Miall et al “local conflicts which are fuelled by global forces may not be resolvable at the local level without changing the structures or policies which have produced them.” Making changes in the structure implies bringing changes in the root causes of the conflict. For example, a structural transformation would imply changing the power relationship between a dominant and weaker party. Actor transformation involves the redefinition of direction or goals. It also involves changes in the perspectives of parties involved in the conflict. Issue transformation is the process, which is tied with the art of reframing the positions of the parties involved. It also depends on the changes in the direction or goals as envisaged by actor transformation. Personal and group transformation is the center of all other transformation processes.

Definition of Frames and Reframing

Framing and reframing are particularly significant in the case of political elites as they recognize that the representations they give of their perception and understanding of political events will have important consequences on the mobilization of large groups in support of their political agenda. For this reasons the conditions for a successful reframing of a conflict will have to be searched both in the subjective dimension comprising identities, perceptions, narratives and motivations of the political elites and in the objective reality of domestic and international political structures and strategic developments that can cause and then facilitate or restrain the actions of political actors.

Once identified the main pre-conditions that allow for a successful reframing of a conflict, they will be applied to the case study of the Oslo Accords to determine to which extent reframing proved to be effective in changing the way parties looked at the conflict and managed to change their relationship significantly.

The widespread use of the concepts of frames, framing and reframing in different disciplines such as psychology, sociology, communication, management, negotiations and conflict resolutions, has both underlined the importance of these concepts as well as created some confusion about what they really mean and to which issues they are applied. There seems to be two main approaches to framing: in the first one, frames are considered as knowledge structures or cognitive representations while in the second one they are considered as interactional co-construction where “interactional alignments are negotiated and produced in the ongoing interaction through meta-communication that indicates how the situation should be understood. Through non-verbal cues or indirect messages, participants signal each other as to how interaction is to be interpreted.”

This thesis will consider frames and framing as the way people “experience, interpret, process or represent issues or relationships and interactions in conflict settings”

People create and use frames to make sense of a situation in order to identify and interpret specific aspects that seem important in understanding the situation, and to communicate that interpretation to others. Entman (1993) expands this definition saying that framing is “to select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation.” In his definition, the frames can also include an evaluation of the situation, an assessment about the actions needed on the problem discussed and potentially a “manipulation” of the public opinion. This need not necessarily to be seen as a negative aspect of framing, but is to be seen in as much as an inevitable one. There is no such thing as a neutral or objective representation of reality, any representation is bound to be subjective by definition and therefore biased. A common denominator in different approaches to framing can be therefore found in the notion that the same issue, problem or conflict can be understood, constructed or narrated in different ways. A frame can therefore be considered a sense-making device, providing meaning to a previously ambiguous situation. In general, it can be said that the way people look at a conflict is not a given, but a constructed reality. This construction of reality can evolve over time, as the economic, social and cultural environment changes, when new parties get involved or when mediators or media become engaged. A conflict is a dynamic process potentially going through a series of different escalation and de-escalation phases that range from latent tension to overt fight from constructive engagement, conflict management and resolution to eventually conflict transformation.. Over time both, the structure of the conflict and its framing change. This is a reciprocal and recurrent process since the framing of the conflict can have an impact on the development of the conflict as well: how parties perceive a conflict may strongly affect the actions people take, influencing the intensity and character of the conflict.

Based on this definition of framing, reframing can then be defined as a change of the cognitive representation of the conflict itself, a cognitive reorientation or a new way to look at the conflict. This change can result either from the acquisition of new data generated by new political and strategic developments or from a different selection or rearrangement of existing data that result in a new narrative i.e. in a new way to make sense of a collective experience. In this process, the political elites of a country play an important role, as they are often the ones that initiate and lead this process of change as they have the means to both acquire a new understanding of current events or past history and the power to create consensus around their new visions.. At all levels, this kind of reframing can “guide us toward developing alternative understandings of ourselves experiencing the conflict; how we view the other person with whom we are in conflict; and the conflict or situation itself.” The way the involved parties or outsiders reframe a conflict can trigger a process of escalation or de-escalation, the continuation or termination of a conflict. Re-framing a conflict can therefore contribute to enhance the ripeness of a conflict and bring about the start of negotiations.

Different Uses of Reframing

A typical use of reframing is the one found in mediation where the mediator simply restates the phrases of the parties using neutral words and eliminating expression that could easily be perceived as aggressive and it could lead to an escalation of the conflict. In the context of negotiations, William Ury had defined reframing as “redirecting the other side’s attention away from positions and toward the task of identifying interests, inventing creative options, and discussing fair standards for the selection of option.” In this perspective reframing goes beyond a minimalistic approach aimed at neutralizing aggressive language and potential escalation to become an active process that can create the necessary space to generate new options based on shared understanding of the issues at stake and the respective interests and needs. It is in this perspective that reframing can unlock its potential providing a different understanding of a conflict and helping bringing about a change in the conflict itself and eventually promoting negotiations.

There are at least six reasons to use verbal reframing:

- Neutralize the language;

- Achieve understanding and/or clarify a statement;

- Help the author of the statement and/or the other participants to achieve a different perspective;

- Identifying the joint or common problem;

- Create a new relationship paradigm;

- Move the resolution process into a more focused phase.

As Neutralizing language: This is probably the most common and frequent use of reframing that is to reword a statement in order to neutralize the language by eliminating aggressive, inflammatory language. During a conflict parties are often locked in verbal exchanges that are marked by harsh judgmental language often based on generalizations and stereotypes that do not leave any space to negotiations and on the contrary end up hardening the positional stance of the parties. A statement might need reframing for a variety of reasons that can be quite evident or more subtle; it can be insulting on a personal basis or using group stereotypes. In any case, the role of the mediator is to translate the offending statement into “neutral terms to remove bias, position and judgment”. This kind of intervention on behalf of the mediator generally allows the parties to address the issues in a more neutral and positive manner. Bernard Mayer calls reframing with this purpose in mind “detoxification” as the unproductive language is removed while the “essential interests” of what is expressed are retained. One of the challenges in cases like this one is to make sure that the rewording preserves both the essence of the underlying concerns and the intensity with which the parties feel them.

To achieve understanding and/or clarify a statement: The image often used in this case is “peeling back the layers of the onion”. Reframing can in fact be used to help the parties appreciate different aspects of the dispute and the parties’ values and beliefs. This happens gradually as a process of trial and error, with the mediator asking questions to the parties and then restating their answers to acknowledge their positions and make sure the underlying interests are uncovered. Through question-induced reframing, the parties may develop a new or varied perspective, which may give them greater insight into the issues. It can give rise to a new paradigm in thinking and to new opportunities for constructive engagement and resolution.

For Creating a New or Altered Perspective: Moore notes that disputing parties each have their own individual and subjective understanding of the issues in dispute and the basis for their conflict. Their perceptions are “images of reality”, which are, in fact, simply interpretations of reality. While the number of potential interpretations is large, Moore observes that an individual’s mindset generally allows for only “one possible, reasonable, permitted view,” which suggests only “one possible, reasonable, permitted solution.” As a result, a party to a dispute will need help in seeing any other point of view or other possible solutions. Using reframing a conflict resolution professional can help the parties generate statements that stripped of their positional rhetoric and imagery can finally allow the parties to hear each other’s points of view, sometimes for the first time. Reframing that focuses on the language that the parties themselves use forces the parties to hear their own statements as the mediator or the adversary heard them. As a result, the parties may choose different words less inflammatory, or more directly related to the issues and to their underlying interests to explain themselves. Reframing to change a party’s perspective however becomes problematic when attempted in a dispute involving value-related issues, such as guilt and innocence, the norms that should prevail in a social relationship, the facts that should be considered valid, the beliefs that are correct, and the principles that should guide decision-makers. While partisanship and bias inevitably will pervade value-laden disputes, Moore suggests that reframing can still play a role. One is to transform a value dispute into an interest dispute. A second is to identify “superordinate” goals with which all parties can identify with and toward which they can join in a cooperative effort.

For identifying the joint or common problem: “Verbal reframing can contribute to the resolution of a dispute by focusing the parties’ efforts on the common problem and on identifying the common goal.” As mentioned above “Moore also suggested this when he recommended using reframing to identify “larger superordinate goals” in value related disputes, and when he discussed framing joint statements of the problem that incorporate the parties’ individual and joint interests. Reframing in order to construct a statement of the common issues in dispute requires the interests of all the disputing parties to be included in the comprehensive statement. Once the parties agree on the statement, they can commit to working together on the common problem because they believe their needs will be respected, if not met, by the solutions that will be developed.”

Conditions for Successful Framing

Objective conditions for a successful reframing

On the structural and strategic level, both domestic and international, there can probably be two scenarios:

- A first one where change is obvious: a major transnational event, either in the military or economic-political arena, triggers wide scale domestic and international change at a systemic level. It is widely acknowledged by the majority of observers as a turning point in the way people look at the world and their place in it. Examples of such a major shift in the international arena could be the end of the Cold War, the first Gulf War and more recently 9/11.

- A second scenario where the structural change is on a smaller scale, but read through the political and military beliefs of the parties involved is perceived as significant enough to start reconsidering the meaning hitherto given to the conflict. The Intifada could be an example of a domestic structural change in a conflict, the Israeli-Palestinian one that contributed to reconsideration of the conflict and to the beginning of a new round of negotiations.

Subjective Conditions for a Successful Reframing

This paragraph will look at the subjective conditions that allow for a successful reframing of identities.

The role of Cognitive Beliefs

The likelihood of political elites changing their perception and outlook on a conflict depends largely on the kind of cognitive beliefs they have on their own identity: who they are and how they relate to the enemy. The belief system of political elites on self and the enemy, in addition to organizing perceptions into a meaningful guide to behavior, has the function of establishing political goals and setting preferences among different options. However, “The belief system and its component images are, however, dynamic rather than static; they are in continual interaction with new information. The impact of this information depends upon the degree to which the structure of the belief system is “open” or “closed”.

In an open belief system, new information is filtered, understood and contextualized in a way that can generate a change in the understanding of the conflict and the behaviors of the political elites. An open belief system can encourage reframing as frame changes occur when new information or direct experience overwhelm filters. An open belief system allows for flexibility of behavior and learning: “Without flexibility in behavior, no learning or adaptation can take place, simply the endless repetition of a maladaptive response. Negotiation, as a special form of adaptation, is of its essence, based on movement, or flexibility of behavior.” On the contrary, in a closed belief system, new information is adjusted to the pre-existing system and there is neither a cognitive reorientation nor a behavioral change.

Furthermore, political elites that have cognitive beliefs characterized by a prospective period, have a proactive attitude towards change, they want to facilitate and be part of it, they are more receptive to new developments and more likely to reframe a conflict because of new political events. On the other hand political elites dominated by a retrospective period, characterized by a conservative and passive approach to change, are often countering any new development in the name of conserving the status quo or returning to some sort of “paradise lost”. In this case, cognitive beliefs are more similar to ideological beliefs they become more abstract, rigid, and change-resistant as based on a set of non-negotiable values often intertwined with religious values.

To sum up, the motivation and willingness of political elites to reframe their cognitive beliefs and representations of self and the enemy because of new political events seem to be facilitated by the following subjective conditions:

- An open belief system that lets in new information and uses it to challenge the status quo as opposed to a closed belief system where the new is adjusted to the old;

- A belief system characterized by a prospective time frame (let’s build the future) as opposed to a retrospective time frame (let’s conserve the present or restore the past);

In addition to these two points, the prevalence of problem-solving negotiations frames, i.e. an attitude to look for a mutual understanding of the conflict and of its solutions instead of power-driven competitive negotiations frames focused on maximizing self-interests in a zero-sum game.

Role of Reframing in Enhancing Conflict Ripeness and Negotiation Readiness

Reframing can be one of the tools used by third party mediators to enhance the ripeness of a conflict and bring parties to the table of negotiations. The theory of ripeness, as well as Pruitt’s theory of readiness, is based on the subjective perception of mutually hurting stalemates and the consequent motivation to move out of a painful situation. In both cases reframing can be effectively used by third parties to increase the motivation to de-escalate the conflict and start negotiating for enhancing the attractiveness of the potential outcomes of negotiations.

Aggestam on Enhancing Ripeness

According to Aggstam, conflict management tends to view change from a static and timeless frame because of the assumption that some basic, unalterable and objective laws are the fundamentals for the determination of international politics. Conflict management therefore presupposes continuance in preference to change and if there is a place for change in the conflict management then it is recognized as an adjustment allowed primarily at the intersection level. In contrast to conflict management, conflict resolution takes into account the notion of change, which describes the ways of moving from conflict to cooperation. As observed earlier change includes the recognition among individuals of the human needs on an universal basis. However, there is a time perspective inherent to the entire process of conflict resolution, which is linear in nature and assumes that altered perceptions of conflict lead to resolution. Aggstam argues that the focus of conflict transformation is mainly on dialectical and systemic change over time from a holistic perspective. He views conflict as an ever-present transformative event. “Change therefore concerns transforming destructive conflict to constructive conflict over time by addressing such key notions as justice and positive peace.”

Aggstam comments that in the search for an appropriate metaphor of change in conflict, practitioners and academics have brought the organic notion of ripeness in to practice which term has become increasingly popular in the conflict and conflict resolution literature. Zartman was the first scholar to introduce and develop ‘Ripeness Theory’. Zartman mentions about the right moment which is the state of ‘mutually hurting stalemate’ and this situation is usually characterized by a deadlock. At this point of time, the parties to the conflict are locked into a situation caused by an impending catastrophe and in intolerable situation. This situation results in a state where the disputing parties reach the levels of adopting unilateral strategies and feel that a negotiated settlement is the only available alternative for further escalation (Zartman, 1986:218).

Aggstam states that ripeness theory attempts to depict a particular situation ( a plateau or a crisis) which makes conflict to mature. Using the cost-benefit analysis, Aggstam provides a description of two distinct positions that ripeness can take.

- based on Zartman’s model of a ‘mutually hurting stalemate’ position makes the conflicting parties realize that the advantage of a politically negotiated settlement is better than the sharp change in the cost of pursuing the escalation of the dispute (Zartman 1986: 219)

- based on Mitchell’s model of an ‘enticing opportunity’ enables the parties to consider the possible future gains. At the ripe moment the parties decide in favor of de-escalation of the dispute because they form an opinion that there are distinct possibilities of achieving certain aims with alternative strategies to conflict (Mitchell, 1995:44-45)

The difference between the two models is based on the assumptions of the parties in the respective situations, which act to motivate the parties to decide engage in de-escalation. If one asks whether the negative experiences such as mutually hurting stalemate or whether the positive expectations lead to the ripeness of conflict, the answer of Aggstam is that both the perspectives fail to appreciate the dynamics of intractable conflicts. For instance, the perspectives cannot reason out why adversaries maintain costly strategies of escalation frequently.

Aggstam mentions of two other theories, which address this problem. They are:

- prospect theory

- entrapment theory.

Prospect theory focuses on the importance of loss aversion. This theory states that individuals tend to become risk-averse when it comes to the question of gains and risk acceptors when it comes to accepting losses (Levy 1996; Stein 1993). On a similar ground “entrapment theory argues that costs often transform into ‘investments’ for the parties, which prevents them from engaging in de-escalation despite the ‘unbearable’ costs of pursuing conflict (Mitchell 1995: 42-43). Therefore, these two theories deviate from rational cost-benefit calculations. The theories offer better understanding of the “framing and continuity of conflict.”

However, these theories do not elaborate much on the process of reframing conflict.

Reframing and ripeness

Ripeness being a thought-provoking notion has forced several scholars to postulate theories on the ways in which a ripe moment in conflict may be linked to the process of negotiation. The concept of reframing can be considered to supersede ripeness in providing the practitioners and mediators advance knowledge about processes that may result in negotiations. The objective of the concept of reframing thus is to direct the attention to process of change in perceptions and normative and behavioral structures. “Reframing may enhance the motivation of political actors to negotiate, provide opportunity which facilitates negotiation, and identify focal points between adversaries that coordinate expectations of a negotiation process.” While ripeness theory attempts to diagnose a situation as ripe, it does not strive to explain the process leading to the ripening of a conflict. One shortcoming of the theory is that it does not elaborate on the motivation of agent in an in-depth way. The ripeness theory is more situation-specific. On the other hand, concept of reframing is a process-oriented understanding of the conflict, which utilizes an agent-structure approach for describing the process of conflict resolution.

The basic understanding of the theory of ripeness is that conflict has moved from an unripe to ripe situation. The ripe situation would favor negotiation and conflict settlement. The temporal dimension of ripeness points towards a sequential timeframe, which enables an organic understanding of the conflict. However, the theory appears to be less clear in providing an understanding of the process of transition from an unripe position to a ripe position of the conflict. It also does not specify how a ripe moment is linked to conflict resolution. There is no explanation as to how ripeness can be sustained and enhanced. Therefore, ripeness in effect is situation-specific and not process-oriented.

On the other hand reframing is more analytical in nature. Reframing is defined as:

“A change in the definition of the relationship between adversaries and of their conflict may enable de-escalation to occur. This often means that the conflict is reframed; the interpretative schema that partisans use to organize and understand their conflict changes… Redefinitions or reconceptualizations of the conflict may come about when it is viewed in a new context, as when a new superordinate shared goal is found.” (Kriesberg 1991: 15)

The objective of reframing is to enhance knowledge of how the meaning of conflict may change. It also aims to understand how interactions characterized by hostility, violence and denial of the enemy will make the conflict move towards cooperation and the resultant acceptance of a negotiated solution. Thus reframing differs widely from ripeness in that reframing is process oriented. It is involved in the reconstructing the reasoning of the conflict before, during and after the incidence of a political event with the objective of how such events may lead to alteration in the meaning of the conflict.

Role of Reframing in Dealing with Intractable Conflicts

Many scholars and practitioners use the term ‘intractable conflicts’ to denote conflicts, which could not be solved or could not be managed effectively. However, one can view these conflicts to resemble closely to the dictionary meaning of the term ‘intractable’ which imply that these conflicts are stubborn or difficult but not impossible to manage. The difference between intractable and other conflicts may be inferred from the difference in the willingness or susceptibility of parties to entertain political options other than violence. In a conflict parties would look for a political settlement at a situation where the costs of continuing to fight starts to outweigh the potential benefits. There are a number of factors, which contribute to the development of this situation like changes in circumstances, elites change, or the public growing weary of the violence and this situation marks the status quo. However, the intractable conflict situations do not recognize these cost-benefit calculations and their impact on the continuance of the conflict. Elites involved in the conflict are not keen in considering negotiated alternatives, because of the fact that the conflict does not harm them any way and there may be a large number of people getting benefits out of the continuance of the conflict. Similarly, there may be a number of “entangled and entrenched” interests which might deter the evolution of a negotiated resolution to the conflict.

Definition of intractable conflicts

There are a number of elements, which characterize intractable conflicts. The first characteristic is that intractable conflicts are typically long-standing in nature and most of them would have existed for years and some even for decades. Some of the intractable conflicts remain unsolved for a prolonged period, despite the taking of many attempts to resolve them. The resolution to such intractable conflicts would not have arrived either through the outright victory of one side or by adopting direct or mediated negotiations. There are instances of some other conflicts, which remain unresolved simply for the reason that no one including the parties to the conflicts ever took any attempt to resolve. “Intractable conflicts are also characterized either by frequent instances of violence or, if there is a temporary cessation of the violence, by a failure by the parties to leave the danger zone of potential renewal of violence.” However, there may be no uniformity in the level of violence across many intractable cases. In some cases, prolonged wars characterized by ongoing military hostilities between parties lead to intractability of the conflicts. In some other cases episodic but recurring violence lead to intractable conflicts. There are some other conflicts which are frozen implying that the violence has ended abruptly; but no permanent solution or resolution has been reached by the parties to the conflict. In few other cases of intractable conflicts, they continue to remain intractable because of the reason that nobody has seriously come forward to assist the parties end their differences through negotiations in appropriate forum.

There is no simple answer to the question as to what makes a conflict intractable. There is no way to identify the factors and forces that give rise to barriers to negotiating to end an intractable dispute. Leadership may be cited as one of the important factors that contributes to intractability. In many cases leaders may have their political careers and personal wealth intertwined with the continuance of the fight and therefore this vested interest makes them take no serious efforts to end a conflict making it intractable. Similarly, the commitment of the individual leaders to the ideals and goals of the struggle and their strong personal identification with such ideals may also prevent them from attempting genuinely end the conflict. The fear of the leaders that permanent peach may harm their personal safety may be another reason for the inactivity on the part of the leaders to take steps to end the violence. Any one of these three reasons may prevent the leadership from looking at a negotiated solution to the violence as an acceptable alternative.

Another way to look at intractable conflicts is to view them as conflicts, which are essentially led by spoilers. Individuals or groups may represent spoilers. This group of people considers negotiation as a breathing space that they could get before they start their next campaign. Spoilers are the people who perceive that people can enjoy greater security because of the continuance of the conflict rather than from the uncertainties of peace. Spoilers may also be leaders who believe that nothing can be achieved through negotiation, because for them unconditional victory is the only outcome that is acceptable and conceivable. A scene for an intractable conflict is set when an equally powerful force, which is determined to stay in power, meets the raised fist of revolution. In these kinds of situations, it is for the third parties to identify and separate the spoilers from those individuals and groups who might show interest in exercising the negotiation option.

“There are however many other factors promoting intractability. These include a lack of resource constraints on both the parties; internal fragmentation or weakness of one or both sides, making compromise and risk taking impossible; uneven or absent linkages to external partners, to third parties, or to regional security mechanisms that could support negotiated outcomes through the provision of credible guarantees, confidence-building measures, verification, and monitoring; and the interest of outside actors in keeping conflict alive.”

One of the most common assumptions that is applied to intractable conflicts is that there is no clearly identifiable formula for resolving such conflicts. In other words there is no obvious solution to the conflict that could be beneficial to both the parties. In such an instance, perhaps efforts have already been taken to negotiate and that have failed (even more than once in some cases). It is more difficult to bring the parties to the negotiating table for the second time than doing it for the first time, because the past experience of the parties would make them think that the negotiations would only fail for the second time also. To sum up the interplay of variables at the elite, societal, regional and global levels lead to the creation of conflicts that are intractable.

Role of Reframing in intractable conflicts

Frame divergence has been one of the causes for the conflicts to become intractable. “Disputants differ not only in interests, beliefs, and values, but also in how they perceive the situation at the conscious and preconscious levels.” These differences in values, interests and beliefs engender divergent interpretation of events. They contribute to painting of parties negative characters yielding mutually incompatible issues. As a result, the differences focus attention on specific outcomes, which have the effect of impeding exploration of alternatives to end the conflicts.

Frame differences lead to increased communication difficulties, because of which parties become polarized, which in turn leads to escalation of strife. Polarization influences the frames of parties and makes them feed stakeholders’ sense that their claim is right and there is no need to compromise on issues. “Divergent frames are self-reinforcing both because they filter parties’ subsequent information intake and color interpretation, and because disputants strategically communicate through these frames to strengthen their positions and to persuade opponents.” Framing and reframing become vital to the communications underlying negotiations in view of the fact parties are linked to “information processing, message patterns, linguistic cues and socially constructed meanings.” Reframing is resorted to find a win-win solution in many conflicts. However, since in the case of intractable conflicts, intractability is unlikely to hinge frames alone, reframing may be helpful but is not considered sufficient often. Reframing alone is unlikely to eliminate intractability. The parties to the dispute may have to recognize not only interests relating to each other but also they need to explore the fundamental needs allowing them to know the frames in use thoroughly. Knowledge on the ways in which frames are constructed enables one to understand and influence conflict dynamics. An insight of framing and reframing would help parties evolve new techniques out of impasse. Interveners can make use of expressed frames to gather an understanding of the situations and to design suitable interventions to end the conflict. Knowledge about the frames of others would help not only in mutual understanding but also in reframing of the proposals in terms, which may become more acceptable to others.

Reframing identities

Knowledge gained from the previous research on conflict framing provides the conceptual base for identity frames. Identity frames exemplify the perceptions of the people about themselves in the framework of particular disputes. Identity frames also enlarge the knowledge on the behavior of individuals as the part of a bigger group and the ways in which they are impacted by the fact of their relationship with and sharing in that group. The notion of identity frames becomes significant as they allow the impact of individuals’ identity and group relationship on the perceptions and response of the individuals to the conflict. Since identity explains the individuals as persons, they tend to protect the identities represented by convictions, significances and group relationships, which help create the logic of oneself. When conflicts threaten or challenge the individuals’ identities, they tend to respond in ways that would help them support their commitment to the relationships. “In a nutshell, identity frames “crop” information and perspectives that do not align with or perhaps contradict features of an individual’s core identity.” There are number of ways in which identity frames are created. They are also influenced by multiple factors. The ways in which individuals will respond in a conflict is influenced largely by the understanding of the individuals of their core convictions, values and sense of self-impact. It is the normal tendency of the people to consider themselves as advocates of a particular set of values (e.g environmentalism, conservation, freedom, equality and the like). They structure the conflict based on the ways the substitutes go forward towards one or more of specific set of interests of the individuals.

Definition of identities

The definition of the term identity varies depending on the persons using it and the context in which they use it. In many fields identity differences are found to be the root cause for the creation of the conflicts. Explanations in the field of social psychology field of conflict find ‘social identity theory’ as the best one to explain the reason for disputes. Self-awareness and self-consciousness form the basis for identity in the realm of sociology. These factors lead to cultural norms and group identities. Within the political field, Identity Politics is used as a tool to search in the reconciliation of frameworks of state’s and shared identities. In the religious studies, one’s beliefs form the largest part of one’s identities. Every social science and other disciplines have some ideas on identity of individuals and the ways in which individuality is related to conflict.

When every individual becomes a mature person, he develops a sense of self and each person’s self-conception tends to be a unique combination of many identifications. These identifications are either broad or as narrow as being an associate of a specific family. “Although self-identity may seem to coincide with a particular human being, identities are actually much wider than that.” Identities are also collective in nature. They also extend to countries, religion and ethnic communities so that people feel hurt and humiliated when other individuals sharing their identity are harmed or killed. In some instances individuals are willing to give up their own lives for the purpose of preserving the individuality of the group. Classic example of this type can be found in Palestinian suicide bombers. “People who share the same collective identity think of themselves as having a common interest and a common fate.”

Sources of Identities

Innumerable traits and experiences form the basis for the creation of identities. Several of these individualities subject themselves to different explanations. One of the good examples is the race. In many of the societies, skin color is a significant factor in individuality. In some other societies this factor has only minimal importance. From the perspectives of some other analysts ethnicity is considered as a phenomenon in deciding the identities. Ethnicity is relatively ancient and unchanging over the period. However, “other analysts stress that ethnicity is socially constructed, with people choosing a history and common ancestry and creating, as much as discovering, differences from others.” There are certain attributes of ethnicity, which are not changed simply by social procedures. “For instance, some traits are fixed at birth, such as parental ethnicity and religion, place of birth, and skin color.” There are some other traits, which may be acquired or modified later, like languages spoken, religion adopted, ways people dress or food habits. “Insofar as the traits chosen to define membership in an ethnicity are determined at birth, ethnic status is ascribed; and insofar as they are modified or acquired in later life, ethnic status is achieved.” Many of the identities are not based on ascribed traits. They find their origin in shared values, convictions or apprehensions and these factors are differently open to achievement by individuals of their own option. Identities have several other characteristics also. They may in some cases be personally perceived and in some others’ ascriptions made about other individuals. While some of the identities endure for generations, some others change swiftly with changing situations. Identities may be exclusive or inclusive in nature. Since people have varied individualities, their relative significance and consistency are subject to variations depending on the specific instances and situations.

Ways of Reframing Identities

Even though intractability of conflicts is largely influenced by many features of identity, there are methods in which individualities can be reframed so that the difficulty of dealing with a dispute can be reduced. The reframing can be attempted through adoption of policies within each group, in the relations between the groups and in the social context of the identities. Reframing policies may vary depending on the phase of the conflict intractability. Six distinct phases of conflict intractability have been identified to be of particular significance. “Six phases are particularly significant: conflict emergence, conflict escalation, failed peacemaking efforts, institutionalization of destructive conflict, de-escalation leading to transformation, and termination of the intractable character of the conflict.” These six phases cannot be considered strictly chronological as some of them may happen together making the dispute return to the previous stage. Therefore, it is essential that policies for reframing are identified to avert disputes from becoming intractable, to curtail the continuation and growth of intractable disputes and to alter and settle intractable disputes.

Reframing Narratives

Some of the divisions of the dispute settlement practitioners have dealt with the concept of reframing rather watchfully. Many of the dispute resolution professionals underpin the importance of reframing the interests and needs of the parties. However, there are other people belonging to some profession, who are of the opinion that mediators because of reframing are likely to force their opinions or approaches on the parties either with intention or without any intention. Despite this opinion and encouragement of free communication, conflict professionals adopt the policy of reframing. Many of the practitioners filtered and expanded additional methods of reframing. One of such techniques is “metaphoric reframing”, which “attempts to find a new or altered metaphor to describe a situation or concept.” Metaphoric reframing is an intensely complicated method to acquire and to practice. The technique requires large amount of compassion to incorporate the fundamental meaning, which the metaphor would like to convey to the parties.

Definition of narratives

Webster’s dictionary defines a narrative as “a discourse, or an example of it, designed to connect a succession of happenings.” American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language defines a narrative as “a story or description of actual or fictional events; or the act, technique or process of narrating.” According to these definitions, a narrative or a story merges actual or probable events. In order to become a narrative, these events should connect in such a way that they provide a chain of events to be recounted to others. There are certain essential characteristics of narratives. All stories or narratives should have a “setting” which term denotes a relationship with particular instances or positions. The followers of the narrative or story may get puzzled if the setting is vague. The second element to be present in a narrative is “characters” representing players in action. With the progress of the story one gain much information about the characters, the way they look like and their dreams and wishes. Third, each narrative should have one “plot.” Plot implies actions, which have results and responses to these outcomes by the characters and for the characters. In a narrative, the starting event ends up in an effort cast on the character and the consequence leads to a reaction. As the story progresses, episodes follow one another and gets built on one another. Within the fundamental structure of the story, numerous differences and reunions occur which have the capacity to improve the pressure of the story. With pressure building along incidents, the need or desire to bring an ultimate resolution is met by one or more of characters. This respite in the form of resolution takes place in the peak or decisive moment in the story followed by offense.

“Jerome Bruner has argued that one of the ways in which people understand their world is through the “narrative mode” of thought, which is concerned with human wants, needs, and goals.” “The narrative mode deals with the dynamics of human intentions.” In the narrative mode, people seek to explain events by looking at the ways human actors strive to undertake actions over time. Once these actions are understood people look at and analyze the impediments that they come across and the intentions that were comprehended or could not be achieved.

There are a number of reasons why people are attracted towards hearing stories – the stories can amuse people, help them to become organized in their thinking, fill them with feelings, keep people in expectation and teach them in how to live act. Stories also talk about various predicaments that are concerned with ethical or unethical behavior. Story telling using spoken or written ways has been considered as a key knowledge in the lives of people. This is the case especially with those people who have experienced sever social sufferings. For example, numerous survivors of Holocaust have narrated their experiences in the form of testimonies in institutions around the world. Even though story telling does not purport to provide any healing for those who narrate them, they are able to open up channels of thoughts, feelings and communications, which have remained closed for years. Palestinians have used storytelling to recount the suffering that they have experienced since they were driven away from their lands over the years. These narratives present the knowledge about Palestinians in their struggles and lives in the Jordanian, Syrian and Lebanese camps and the stories talk about the aspirations Palestinians to return to their previous houses.

The role of narratives in Conflict Resolution

“The recounting of personal stories in situations which aim to reduce inter-group conflicts and to enhance peace-building and reconciliation between adversaries has been used within the last decade in a number of contexts around the world.” One of the examples in the context is the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) established in South Africa in the year 1995 for providing relief from some of the deep wounds of Apartheid years. Story telling was the main vehicle used by TRC for this purpose.

“…The objectives of the Commission shall be to promote national unity and reconciliation in a spirit of understanding which transcends the conflicts…of the past by…establishing as complete a picture as possible of the causes, nature and extent of the gross violations of human rights which were committed during the period… including… the perspectives of the victims and the motives and perspectives of the persons responsible for the commission of the violations…the granting of amnesty to persons who make full disclosure of all the relevant facts relating to acts associated with a political objective…and …making known the fate or whereabouts of victims and by restoring the human and civil dignity of such victims by granting them an opportunity to relate their own accounts of the violations of which they are the victims…” (No. 34 of 1995: promotion of national unity and reconciliation act, 1995).

Storytelling and narratives are being used to reduce conflicts even from the year 1990. The role of narratives can be found in the process of reconciliation between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland and between Blacks and Whites in South Africa. Storytelling has been used in reaching a solution for the conflict between Palestinians and Israelis and between descendants of Holocaust survivors and Nazi perpetrators. “Two examples of institutions/groups in which I am involved that use stories and storytelling for these purposes are PRIME – the Peace Research Institute in the Middle East and the TRT – To Reflect and Trust.”

PRIME is a non-governmental organization (NGO) involved in the research relating to Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This organization undertakes cooperative social research studying various issues that have great importance for both Palestinians and Israelis. Research projects are planned with the objective of exploring important aspects of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict form psycho-social perspectives and to utlize the results of the research for peace-making initiatives. PRIME has currently running of two of its projects, based on narratives and storytelling.

“The TRT is an international organization that began in 1992 as an encounter group between descendants of Nazi perpetrators and of Jewish Holocaust survivors.” Meetings are arranged between these two groups of individuals in a self-supporting atmosphere. They tell life experiences to each other with the objective of to gain a better understanding to cope up living with their paste experiences, because of their parents’ encounters while World War II was in progress.

Ways of Reframing Narratives

Political elites communicate their cognitive and ideological beliefs to their electorate through competing cognitive representations or narratives or frames that give meaning to a national identity recounted through a storyline from the origins to the present time, through critical events and trials that are chosen among many for the power they have to crystallize and reinforce either the reasons of old grievances or the unique nature of the national character.