Abstract

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) is equity or equity-linked investments in young privately held companies where the investor is a financial intermediary of a non-financial corporation. While many entities offer finance for entrepreneurs, such as banks, venture capital, IPO, and others, CVC differs from them in the sense that its involvement is deeper and closer. The CVC may invest in a venture not only for financial prospects but also for many other reasons like education and training and to achieve strategic objectives.

Differing from other funding entities, CVC attempts to add value to the acquisition by using a variety of means. A research question has been framed “How do corporate venture capital back and acquisition create value for the acquiring company?” The paper has conducted research to create an understanding of the methods used by CVC to create value by using a balanced financial structure with joint control and cash flow.

The paper would point out that while finance is very important to a venture if the CVC imposes very rigid controls over the finance, the entrepreneur would feel threatened and consequently lose interest. On the other hand, if there is no accountability expected from the venture on how the funds are being used, this would lead to a very unhealthy situation. The paper has examined the issue of joint control and cash flow in detail.

Introduction

The CVC involvement in ventures extends to more than just providing capital and finance. They get involved at a much more intense level than other funding entities. The paper has framed a research question and proposed six hypotheses that explain the question. These hypotheses have been supported by literature review and research. The paper has examined the role of CVC and has provided a conceptual framework for the study. The paper has examined the financial investment pattern of CVC to understand how finance is disbursed at various stages of the project. From the wide reasons as to how CVC infuses value to the venture, the paper has shown how joint control and cash flow best help to add value to an enterprise.

The paper would help students and researchers to obtain an integrated view of CVC and how it adds value. Previous literature has focused on specific areas such as finance, sales, and marketing, productions, etc., but this paper provides a unique and integrated encapsulation for different theories and provides a definitive view on how CVC adds value to a venture.

About CVC

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) is defined as the “purchase of mostly minority equity positions in independently managed start-ups or growth companies by an established corporation.” CVC study is considered important since CVC is widely used in different industries; it has had its share of success and failures in leveraging enhanced productivity and benefits. In 2000, in the US, the absolute level of CVC investments was at 21 billion USD, out of which 17.4 billion USD was invested in start-ups, and the remaining 3.4 billion USD was invested indirectly by non-financial corporations and committed to VC funds as limited partners.

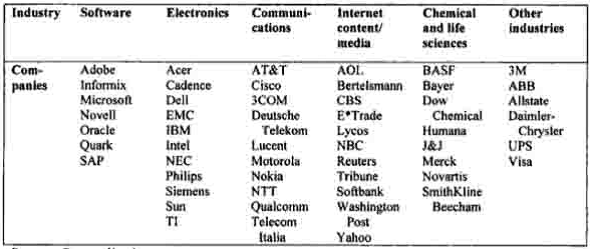

Some prominent companies such as Dow, DuPont, Ford, General Motors, Exxon, and others started CVC activity in the late 1960s. There are more than 240 CVC companies across the world, and there is a strong pitch towards funding Internet-enabled services and technology companies, software, and communications (Poser, 2003).

Research Question

Corporate Venture Capitalists (CVCs) provide finance to upcoming and unknown companies and provide them with the required finance and support to get them started (Dushnitsky, 2005). Maula (2001) has defined CVC as “equity or equity-linked investments in young privately held companies” where the investor is a financial intermediary of a non-financial corporation. The main difference between venture capital and corporate venture capital is the fund sponsor.

In CVC, the only limited partner is a corporation or a subsidiary of a corporation. While seed money is one of the key driving forces and the means to get a business rolling, the involvement of CVCs is not limited to only providing finance and then taking a backseat like a silent partner and wait for results to come in. CVCs, on the other hand, take an active interest in the company they have invested in and add value to it.

The research question that term paper will attempt to answer the question of “how do corporate venture capital back acquisition create value for acquiring company?” While ample literature is available on the manner that CVCs function and the benefits that they provide, a single published work that provides empirical evidence on how they add value has not been published. This paper will conduct an extensive literature review to explore the extent of involvement of the CVCs in managing the affairs of the company they have invested in and investigate the expertise that they bring in that adds to the competitive advantage of the companies.

Conceptual Framework

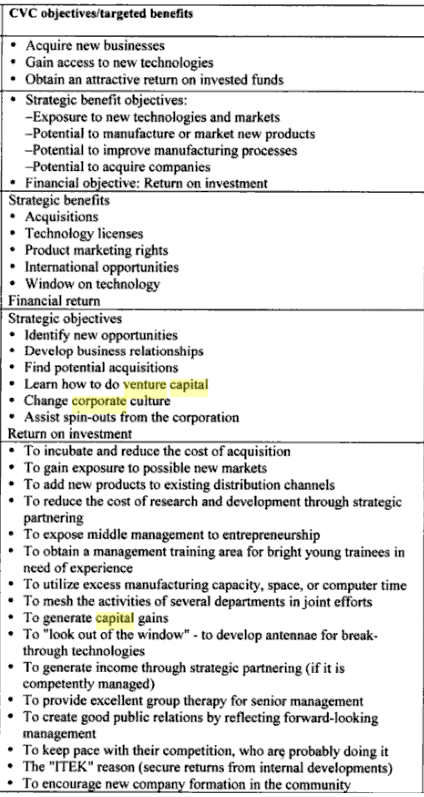

Established companies focus on strategic and financial objectives with CVC. Strategic objectives are generally considered most important for corporations, and some of them identify new opportunities, develop business relationships, find potential acquisitions, and learn how to do venture capital, change corporate culture, and assist spinouts from the corporations. Factors that are identified as important for the success of CVC include: formulating clear objectives with a financial and strategic focus, commitment from top management, staffing skilled CVC managers with appropriate compensation, frequent contact, and working relations with the funded start-ups, etc. (McNally, 1997).

To discuss the research question, some key terms will be studied. They include understanding different frameworks, analyzing different models, and discussing sustainable competitive advantage. The paper then frames six hypotheses that would state how CVC adds value to the question. Further chapters would undertake an extensive literature review to prove the hypothesis.

Analysis of different Frameworks

Maula (2001) has analyzed seven different frameworks that form the basis of organization development and growth. The seven frameworks are resource-based view of the firm, knowledge-based view of the firm, social capital theory, resource dependence perspective; asymmetric information and signaling theory; agency theory, and transaction cost economics. The following table compares the theoretical approaches in research in inter-organizational relationships and the conceptualization and behavioral assumptions. The following table provides a summary of the frameworks.

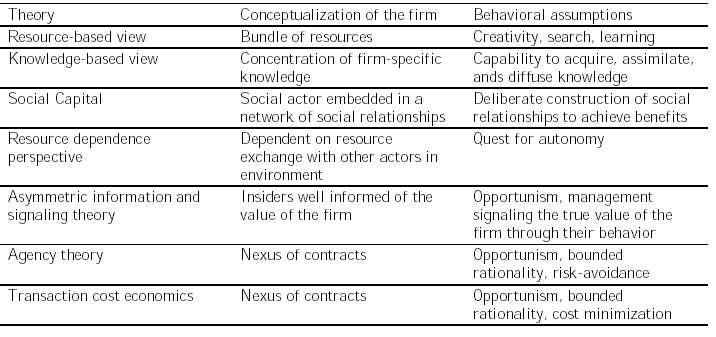

The following table provides the comparison of the theoretical approaches in research in inter-organization relationships and provides the notion of inter-organizational relationships and main motives.

Theory Development

The paper would build up more on the concept of sustainable competitive advantage and how CVC helps in achieving it. The theory would examine the importance of sustainable competitive advantage and develops an understanding of CVC.

Theory

To explore and analyze the research question, a theory will be developed to explain the concept of sustainable competitive advantage and how CVC. After explaining the key terms, a theory and hypothesis would be framed.

CVC: Investing or Diversification

There is a general difference in understanding the concept of CVC investment, and arguments have been offered that CVC invests or seeks diversification, and the section suggests another means to know how CVC adds value to a company (McGrath, 1995, 1994)). Kazanjian (1987) has argued that generating ideas is necessary but that “they are not a sufficient condition for successful internal diversification.” CVC firms tend to review the progress of the structurally differentiated group and screen ventures for further development and testing. A misjudgment can lead to danger is when CVC may prematurely reject ventures for diversification.

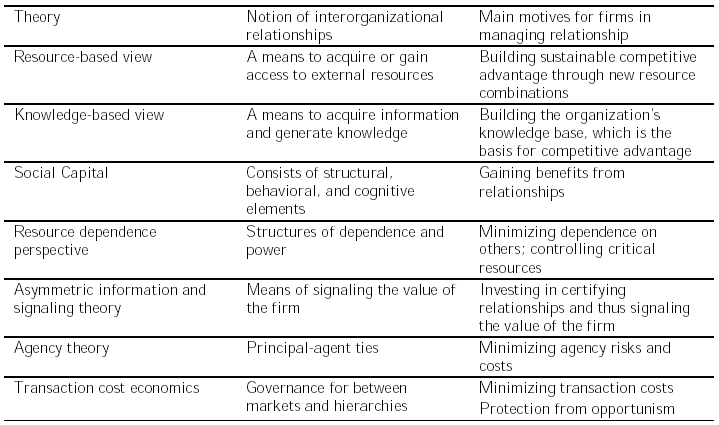

Dushnitsky (2005, 2006, 2004) speaks of “integrating issues” as one of the causes of new venture failures, and by applying bureaucratic principles of review and control resulted in power conflicts between managers and senior executives, and product managers. CVCs ensure that excessive corporate control over-funded ventures is reduced. Please refer to the following figure that illustrates the diversification process used by CVC.

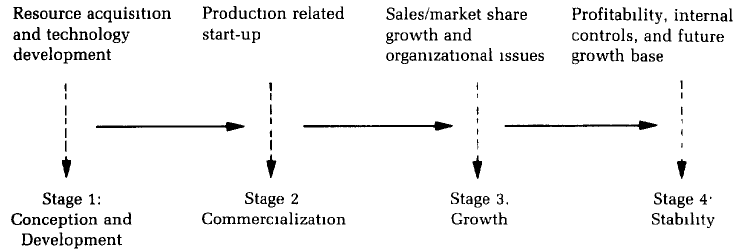

Kazanjian (1988) has pointed out that CVCs tend to use a “stage development pattern” in investing and adding value to a company. The authors point out that a certain amount of handholding is done by the CVC in the initial stages when new ventures face strategic and operational problems from the time of product conceptualization through organizational maturity. Some of the problems seem to be more dominant than others at times, and a sequential pattern of dominance seems to exist. The particular problems faced at a given time appear to be strongly associated with a venture’s position in a particular stage of growth. As soon as the dominant problems change, organizational design variables changes in response.

The above figure depicts the conception and the development stage. It relates to the stage of which formal creation is signified by incorporation or gaining a major source of financial backing. The latter is beyond the initial seed grants, in which companies go through a period during which the primary focus of the entrepreneur is on the invention and development of a product or a technology. CVC often steps in when structure and formality during this stage and all activity is focused on technical issues as defined and directed by the founders.

An early association with the founders helps the CVC to understand the ground realities, understand the progress, and know where the success is heading. CVCs often provide funding at this stage to pay salaries, develop basic infrastructure, and develop prototypes and so on (Kazanjian (1988).

Framing the theory and hypothesis

Based on the previous discussion, the following hypothesis is proposed for the research question, which is “How do corporate venture capital back acquisition create value for the acquiring company?”

- CVC adopts allocation of formal and joint control and cash-flow rights in venture capital deals to remove the feeling of excessive controls so that entrepreneurs do not feel threatened

The next sections would provide an extensive discussion of how the hypothesis can be tested to understand how CVC adds value.

Methodology

The paper proposes to use extensive literature to provide quantitative and qualitative evidence that would attempt to prove the hypotheses. The literature review would start with investing patterns of CVC and study different theories, models, and empirical evidence.

A number of peer-reviewed journals have been used along with other publications to develop an understanding of the factors that make CVC involvement in ventures successful. The review has focused on literature that gives a divergent view about the various hypotheses that have been used.

Literature Review

The literature review will attempt to discuss the various aspects of CVC, then link the various aspects of CVC to how it adds value to a company. The literature review would also attempt to prove the different hypotheses that have been framed.

Investing Strategy of CVC Fund

Hippel (1977) suggests that a “compelling investment strategy is an important resource that significantly impacts the competitive advantage of venture capitalists.” The investment strategy is based on qualifications like industry expertise, analysis capabilities of VC experience. An investment strategy has different elements: management approaches for accessing deal flow, performing due diligence, and monitoring/ supporting start-ups, as well as possibly a specific investment focus. The investment focus is an important element of an investment strategy since it predetermines what types of investments a fund intends to make.

McGrath (1994) comments that “in order to create a compelling investment strategy, venture capitalists typically focus on funding certain fields of expertise or a primary access to deal flow,” the CVC has specific expectations about technological development, the IPO market may be receptive to certain groups of start-ups, certain fields may lack a supply of venture capital, etc. Three criteria are often used to focus on investment strategy: the investment stage, the sector, and the geographic region.

McGrath (1995) further suggests that “an investment focus may be on a specific investment stage: seed, start-up, expansion, etc.” Explaining further, the authors point out that investment stages include acquisition financing, management/ leveraged buy-out financing, management buy-in, or turn-around financing. Acquisition financing provides funds for the acquisition of another company.

Management/ leveraged buy-out financing enables an operating management group to acquire a product line or business from either a public or private company. Management buy-in financing enables managers from outside the company to acquire a product line or business. Turn-around financing is provided to companies at a time of operational or financial difficulty with the intention of turning around or improving a company’s performance.

According to McNally (1997), “financial success can be considered as a prerequisite for strategic success.” Strategic benefits such as successful business relations with the funded start-up do increase the likelihood that the start-up will be successful and generate financial returns for its investors. Financial objectives are easily specified as return on investment, and this is typically expressed as an internal rate of return or IRR. Strategic objectives may be different from financial, and the following table provides a list of financial and strategic benefits that form part of the CVC objective.

Besides financial objectives, strategic objectives are listed, containing various targeted strategic benefits. The financial return is not sufficient to guarantee strategic returns firm CVC. In some cases, successful start-ups may not automatically deliver strategic value. Start-ups may become successful without any contact with the investing company. Contact, however, is a prerequisite for achieving strategic success. “Apple achieved an internal rate of return of approximately 90% over five years, but it had little success in improving the position of Macintosh, its strategic objective.” A company needs to determine what level of IRR it wants to target (Li. 2006).

Chesbrough (2002) has argued, “CVC programs that invest in activities that are unrelated to their strategy and their capabilities are wasting their shareholders’ money.” He argues that “Just as corporations add no value to their shareholders by diversifying their businesses, so two shareholders can invest in private equity opportunities without the help of the corporation.” Only CVC investments that relate to the strategy or capabilities of the corporation warrant the use of shareholders’ funds.

Joint Control and Cash Flow in CVC

While cash flow is very crucial in a CVC, the issue of control can make or break the start-up. CVCs realize that if they put in maximum controls over an organization, there is the danger of choking off innovation and creativity and antagonizing the venture founders who may feel threatened (Cestone, 2001). The authors point out that those investors “control rights are allocated independently of cash-flow rights, through different sets of covenants.” One notable example is the widespread use, in venture capital deals, of several classes of common stock to which are attached very different voting, board and liquidation rights.

Hence, the complex set of rights attributed to investors cannot be exhaustively described by standard securities like common stock, debt, or preferred stock. This suggests that venture capital contracting theory focuses on the allocation of different rights through contractual covenants rather than on the use of a particular security. Further analysis of the author’s research suggests that CVCs’ control is “positively correlated to the performance sensitivity of the entrepreneur’s cash-flow rights.” In addition, when VCs have voting control, their cash-flow rights are more likely to take the form of preferred stock. More generally, contractual terms increasingly adopted in the corporate world display similar characteristics.

Cestone (2001) points out that in corporate venturing deals and sophisticated partnership deals between biotech start-ups and big drug companies, the corporate investor typically takes a majority equity stake in the emerging start-up but few or no seats on the board of directors. The authors have argued, “Two non-contractible factors are crucial for the start-up’s success.” First, at the seed stage, the entrepreneur must exert enough effort in pursuing research and analyzing the different projects available.

At a later stage, after research has been carried out and the controlling party has selected a project, the venture capitalist must give professional advice in formulating the firm’s strategy, provide introductions to potential customers and suppliers, help recruit key employees. The authors contend that venture capitalist’s real control over project selection discourages entrepreneurial initiative.

Aghion and Tirole (1997) have pointed out that “the central trade-off is one between the entrepreneur’s early incentives and the venture capitalist’s late incentives.” To induce VC support, one would like to sell the venture capitalist a very risky claim.

However – if CVC is granted formal control over project selection – a risky claim induces excessive VC interference, which in turn kills entrepreneur initiative. In other words, when a venture capitalist holds a risky claim, the cost of the formal control in terms of entrepreneurial initiative may become too high. This trade-off formalizes a typical entrepreneurial attitude towards venture capitalists: on the one hand, entrepreneurs like VC investors support their firms with professional advice and connections. On the other hand, entrepreneurs are unhappy with VCs who exercise too much control over the firm.

Hippel (1997) argues that an appropriate design of “financial claims and control rights enable entrepreneurs to induce CVC support which is the bright side of venture capital, while limiting VC interference which is the dark side of venture capital.” When the need for CVC support calls for very high-powered incentives to the investor, the entrepreneur retains control, thus avoiding any risk of interference.

In the optimal arrangement, the venture capitalist will hold cash-flow rights that resemble either common or preferred stock. When CVC support matters, the venture capitalist holds a class of common stock with no formal control, whereas the entrepreneur holds preferred stock and retains control. When the CVC support is not very costly or un-essential, the CVC holds preferred stock, but it is given formal control. This result challenges the widespread idea that common stock should always be associated with more control rights with respect to preferred stock and is in line with the use – in real-world CVC contracts – of classes of common stock with very limited control rights attached.

Holding Patterns and Controls

The contract between an entrepreneur and a CVC is inherently incomplete because it is neither feasible nor credible to describe all possible future actions and contingencies in the contract. Therefore, the contract places special emphasis on the allocation of control rights, which gives the controlling party the right to make decisions not specified in the contract. In practice, contracts between CVC and entrepreneurs separately allocate board rights, voting rights, and other control rights; moreover, these rights are often contingent on future measures of firm performance. Two common features of these contracts are particularly noteworthy (Kaplan and Stromberg, 2000).

First, in most CVC firms, neither the entrepreneur nor the CVC has exclusive authority over some of the key corporate decisions, like choosing the manner of the CVCs exit from the firm, and such decisions can only be taken by the approval of both the agents. In other words, the control allocation resembles the so-called “joint control.” For instance, in their study of US venture capital contracts, Kaplan and Stromberg (2000) find that in 61% of CVC firms in their sample, neither the venture capitalist nor the founder manager controls a majority of the board seats.

Since the other members of the board are chosen by the mutual consent of the entrepreneur and the venture capitalist, this means that neither of the agents has exclusive authority to make crucial decisions. Cumming (2002), in his study of European venture capital contracts, also points out that CVC commonly holds veto rights over decisions involving asset purchases, asset sales, issuance of equity, etc. As I explain later, the prevalence of joint control in venture capital contracts is puzzling because it contradicts theoretical predictions that joint control is suboptimal except under limited circumstances that do not match the characteristics of venture capital financed firms.

Second, CVC commonly holds a redemption right, which gives the CVC a right to demand that the firm redeem its liquidation claim, failing which the CVC might get board control and/ or right to sell the company.

Kaplan and Stromberg (2000) report that redemption rights are present in 79% of all CVC contracts they survey, with a typical maturity of five years. Previous explanations of redemption rights have appealed to the abandonment option associated with debt financing. But as Kaplan and Stromberg (2000) note, “the abandonment option argument does not apply well to redemption rights that apply so far into the future.” This is because poorly performing firms are generally liquidated in under four years.

A firm’s “financial slack,” or the difference between its expected cash flows and its required investments and monitoring costs and the severity of the conflict of interest between the entrepreneur and the CVC, has to be considered in equal measure. When there is a conflict of interest between the entrepreneur and the venture surrounding future decisions, the cash flow rights of the agents must be assigned in such a way that the agent in control of the firm has incentives to take the efficient decision.

This may prove to be infeasible when the conflict of interest is very severe and when the expected cash flows of the firm are not high enough, i.e., when the firm’s financial slack is low. Under such circumstances, assigning control to both the entrepreneur and the venture capitalist and specifying a harsh penalty such as termination of the relationship or “liquidation” if they fail to reach an agreement is better than assigning control exclusively to either of the agents. A redemption right makes the threat of inefficient liquidation credible, thus preventing a costly stalemate, and also enhances the bargaining power of the CVC in future negotiations (Berglof, E, 1994).

Joint and Individual Control Arguments

The start-up firm will be faced with some important decisions, the nature and timing of which cannot be described in the contract. The decision that determines the manner of the venture capitalist’s exit from the firm: should the firm undertake an IPO or be acquired by a larger rival? The preferences of the entrepreneur and the CVC are likely to differ significantly over this decision. The entrepreneur values control rents in addition to financial returns and may choose the IPO route to safeguard control rents even when the financial returns from an acquisition are higher.

On the other hand, the CVC may prefer an exit route that yields financial returns quickly and requires less effort to monitor and manage the firm. So the CVC may choose the acquisition route prematurely, especially when its liquidity constraints and cost of continuing to monitor and manage the firm are high (Dessein, W. 2005).

Since the contract cannot resolve this potential conflict of interest, it assigns control over the decision either to one of the agents (individual control) or to both the agents simultaneously (joint control). Under joint control, a decision is made only if both agents agree to it; the agents face the threat that if they fail to reach an agreement, the relationship between them would be terminated (“liquidation”). As will become apparent, this threat of inefficient liquidation under joint control is instrumental in getting the agents to agree to the efficient exit decision.

Under individual control, the agent who has control needs to be provided incentives to choose the efficient decision. Moreover, since the entrepreneur has no personal wealth and since the CVC is constrained for funds, these incentives must come from the firm’s cash flows. So when the entrepreneur is in control, they need to be rewarded for choosing the acquisition route, in the form of compensation for the control rents forgone. Similarly, when the CVC is in control, it needs to be punished for choosing the acquisition route in order to dissuade it from choosing such a route prematurely. So under both forms of individual control, the CVC payout under the acquisition route must be low if the optimal exit route is to be chosen.

But at the same time, the expected payout to the CVC must be high enough to persuade it to invest in the firm in the first place. These two conflicting objectives may be difficult to reconcile when the firm’s “financial slack” is low, entrepreneur control rents are high, the CVC liquidity constraints are high, and the firm is costly to manage and monitor. For such firms, both entrepreneur control and venture capitalist control may be sub-optimal (Dessein, 2005).

Joint control doesn’t require punishing the CVC when the firm chooses the acquisition route. The reasons are as follows: First, faced with the threat of inefficient liquidation, the entrepreneur will not insist on obtaining compensation for control rents before agreeing to the choice of the acquisition route when it is optimal. Second, since control is jointly held, the CVC cannot force an acquisition on the firm prematurely. So joint control results in the optimal decision being made. The only remaining issue is whether the expected payout to the CVC is high enough to persuade it to invest in the firm or not. This depends on the payout that the CVC can extract in future negotiations, which in turn depends on its ex-post bargaining power and the liquidation value of the firm that it can threaten to seize (Hellmann, T. 1998).

The optimality of joint cash control

Cai (2003) and Hauswald and Hege (2002) derive the optimality of joint cash control in a setting where two agents make relationship-specific investments that are non-contractible. Cai (2003) argues that when agents face a trade-off between relationship-specific investments and general investments to promote their outside options, joint ownership acts as a mutual hostage and promotes cooperation by committing the agents to the relationship.

However, this does not explain the prevalence of joint control in CVC firms because contracts between CVC and entrepreneurs generally include mechanisms like non-compete clauses, time vesting of stock options, etc., to restrict the entrepreneurs’ outside options and to commit them to the relationship. Hauswald and Hege (2002) show that when agents face a trade-off between investment and control rent-seeking activities, a 50-50 ownership may be optimal because it offers protection against rent-seeking activities.

The optimal ownership in their model is determined by the relative resource costs of the two agents; joint 50-50 ownership is optimal when the scope for value diversion is high or when the resource costs of the two agents are similar. Hence joint control serves as a mutual hostage and ensures that both parties are kept in line and value is given to the venture.

The hypothesis “CVC adopts allocation of formal control and cash-flow rights in venture capital deal to remove the feeling of excessive controls so that entrepreneurs do not feel threatened” has been proved.

Findings and Discussions

]The previous sections have brought to light some salient facts about CVC and how they add value to a funded company. A hypothesis has been framed that “CVC adopts allocation of formal control and cash-flow rights in venture capital deal to remove the feeling of excessive controls so that entrepreneurs do not feel threatened.” This hypothesis has been tested by reviewing different literature and proved.

The study has shown the importance of joint cash controls for both the CVC and the entrepreneur. Such a mechanism ensures that while cash is available for the business, no single entity can dominate over the venture. The entrepreneur who usually needs funding is fully dependant on the CVC for finance, and in the initial stages of the project, when seed money is very important to get a project started, cash control is very crucial.

At this stage, a venture has only ideas and maybe a working demo model or a viable business model but nothing concrete. To show quick results, finance is very important, and money needs to be spent on hiring people, machinery, equipment, and other infrastructure. At this stage, the entrepreneur should be able to spend money as he sees fit and without excessive controls from the CVC.

Sufficient leeway in the form of spending money helps in getting the project off the ground and gives the entrepreneur ample freedom, and this feeling encourages creativity, brings out initiative and feelings of trust. At the same time, the CVC, which has invested money, needs some assurance that the money is being spent wisely and there is some accountability. Joint controls help to assuage feelings of insecurity for both parties, bring transparency into financial dealings, and, more important, removes any feelings of dependency for both parties.

Anticipated results and analysis of findings

The hypotheses that have been proved help us to define a broad framework that shows how CVC creates value for a company. It needs to be understood that there are many other factors that make the difference between success and failure, and the reasons for success are not limited to these factors.

The findings highlight how joint cash control allows proper flow of cash, removes hoarding tendencies for both parties, and brings accountability into the transactions without excessive feelings of repression or control over the entrepreneur by the CVC. The findings also show when agents face a trade-off between relationship-specific investments and general investments to promote their outside options, joint ownership acts as a mutual hostage and promotes cooperation by committing the agents to the relationship. Since contractual obligations are not strongly enforced in such ventures, accountability is taken care of since both parties must act in concurrence. So joint cash controls induce more cooperation, more patience, and trust in a venture.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The paper has researched some of the factors that help CVC to add value to a venture. Six hypotheses have been framed and proved with the literature review that offers strong arguments in favor of adopting the right approach. One of the important points is that the entrepreneurs should not see CVC help as undue interference. The study has also discussed how cash flows can be made to the venture without making the entrepreneur feel threatened or frustrated. Some CVCs adopt funding at different stages of the project and after certain predefined milestones have been achieved.

Recommendations

The industry has many different drivers, where technology keeps changing very fast. Hence, the issue of core competence of the CVC is very important. A CVC that is active in the automobile industry cannot be expected to offer expert guidance and handholding to a venture in the telecommunication domain. Thus, further studies should be more case studies oriented, with the intention of deep focusing on specific industries and companies.

It is recommended that studies that show the actual cash flows be taken up as such a study will highlight the impact of phase-wise disbursing of funds. Ideally, a CVC would disburse funds based on the development of different milestones achieved. A study that shows how milestone achievement is impacted both positively and negatively is required to understand the impact. The role of CFOs in the CVC needs to be understood, and the modalities of contracts adopted to effect joint cash control flows are required. Such a study would help in developing a framework and a model that could be used for implementing a venture.

It is also recommended to study the balance sheets and statement of accounts of both the CVC and the venture since such a study would show how much of the adverse financial impacts during the initial stages of a venture are being passed on the CVC. Such a study would also reveal the accounting heads, such as business expenses, that the CVC may adopt to keep the accounts in line with the government regulations. Such a study would also reveal the financial adjustments that CVC makes to balance their accounts and the tax write-offs that CVC may claim.

It is also recommended that suitable case studies should be taken of the project life cycle with special reference to the funding strategies adopted by CVC ventures. Such evaluations of case studies would show the manner in which ventures become successful.

References

Aghion, P. and P. Bolton. 1992. An Incomplete Contracts Approach to Financial Contracting. Review of Economic Studies. Volume 77. pp: 338-401.

Berglof, E. 1994. A control theory of venture capital finance. Journal of Law, Economics and Organizations. Volume 10. Issue 2. pp: 247–267.

Burgelman Robert A. 1983. A process model of Internal Corporate Venturing in the Diversified major firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, Volume 28. pp: 223-244.

Burgelman Robert A. 1985. Managing the new Venture Division: Research findings and implications for strategic management. Strategic Management Journal. Volume 6. pp: 39-54.

Burgelman Robert A. 1988. Strategy making as a social learning process: The case of Internal Corporate Venturing. Strategy Organizational Studies Decision making. Interfaces. Volume 18. pp: 74-85.

Cai, H. 2003. A theory of joint ownership. Rand Journal of Economics. Volume 34. pp: 63–77.

Cestone Giacinta. 2001. Venture Capital Meets Contract Theory: Risky Claims or Formal Control.

Chesbrough Henry, Tucci Christopher. 5 February 2004. Corporate Venture Capital In The Context Of Corporate Innovation. Paper presented at the DRUID Summer Conference.

Chesbrough, Henry, and Socolof, Stephen, 2000. Commercializing New Ventures from Bell Labs Technology: The Design and Experience of Lucent’s New Ventures Group. Research-Technology Management. pp: 1-11.

Collis D. 1991. A resource based analysis of global competition. Strategic Management Journal. Volume 12, Special Issue. pp: 49-68.

Cohen, W. M., D. A. Levinthal. 1990. Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly. Volume 35. Issue: 1. pp: 128-163.

Cumming, D. 2002. Contracts and exits in venture capital finance. Working Paper.

Dessein, W. 2005. Information and control in ventures and alliances. Journal of Finance. Volume 60. Issue 5. pp: 2513–2549.

Dougherty Deborah. 1995. Managing your core incompetence’s for Corporate Venturing. Journal of Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. pp: 113-135.

Dushnitsky, G. and M.J. Lenox. 2005. “When Do Firms Undertake R&D by Investing in New Ventures? Strategic Management Journal, 26(10):947-965.

Dushnitsky, G. and M.J. Lenox. 2005. “Corporate Venture Capital and Incumbent Firm Innovation Rates” Research Policy, 34(5):615-639.

Dushnitsky, G. and M.J. Lenox. 2006. “When Does Corporate Venture Capital Investment Create Firm Value?” Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6): 753-772.

Dushnitsky, G. 2006. “Corporate Venture Capital: Past Evidence and Future Directions,” in Casson, Yeung, Basu & Wadeson (eds.) Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurship, Oxford University Press.

Dushnitsky, G. and M.J. Lenox. 2005. “When Do Firms Undertake R&D by Investing in New Ventures?” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 2005: Proceedings of the 25th Annual Entrepreneurship Research Conference.

Dushnitsky, G. 2004. “Limitations to Inter-Organizational Knowledge Acquisition,” Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings.

Dushnitsky, G. and M.J. Lenox. 2003. “When Do Firms Undertake R&D by Investing in New Ventures? Academy of Management Best Paper Proceedings.

Fisher Brendan P., Erickson, Jon D. 2007. Growth and equity: Dismantling the Kaldor–Kuznets–Solow consensus. Ecological economic theory. pp: 53-72.

Hauswald, R. and U. Hege. 2002. Ownership and control in joint ventures: Theory and evidence. Working Paper.

Hellmann, T. 1998. The allocation of control rights in venture capital contracts. Rand Journal of Economics. Volume 29. Issue 1. pp: 57–76.

Hippel Eric Von. 1977. Successful and Failing Internal Corporate ventures: An Empirical Analysis. Journal of Industrial Marketing Management. Volume 6. pp: 163-174.

Hochberg Yael V. 2003. Venture Capital and Corporate Governance in the Newly Public Firm. Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University.

Hornsby Jeffrey S., Kuratko Donald F., Zahra Shaker A. 2002. Middle managers’ perception of the internal environment for corporate entrepreneurship: assessing a measurement scale. Journal of Business Venturing. Volume 17. pp: 253-273.

Kaplan, S. and P. Strömberg. 2000. Financial Contracting Theory Meets the Real World: An Empirical Analysis of Corporate Venture Capital Contracts. CEPR Discussion Paper. No. 2421.

Kazanjian Robert R, Drazin Robert. 1987. Implementing Internal Diversification: Contingency Factors for Organization Design Choices. Academy of Management Review. Volume 12. Issue 2. pp: 342-354.

Kazanjian Robert R. 1988. Relation of dominant problems to stages of growth in technology based new ventures. Academy of management journal. Volume 31. Issue 2. pp: 257-269.

Li Yong, Mahoney Joseph T. 26 August, 2006. A Real Options View of Corporate Venture Capital Investment Decisions: An Empirical Examination. Annual Academy of Management Conference (AOM), Atlanta.

McGrath Rita Gunther, Venkataraman S., MacMillan Ian c. 1994. The advantage chain: Antecedents to rents from internal corporate ventures. Journal of Business Venturing. Volume 9. pp: 351-369.

McGrath Rita Gunther. 1995. Advantage from adversity: learning from disappointment in internal corporate Ventures. Journal of Business Venturing. Volume 10. pp: 121-142.

McNally Kevin. 1997. Corporate Venture Capital: Bridging the equity gap in the small business sector. Rutledge Studies in Small Business, London. ISBN: 0415-154677.

Maula Markku VJ. 2001. Corporate Venture Capital and the value added for technology based new firms. PhD Dissertation, Helsinki University of Technology.

Nonaka Ikujiro. 1994. A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science. Volume 5. Issue 1. pp: 14-37.

Porter E Michael, 1988; Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors; Free Press, Ist Edition; ISBN-13 978-0684841489.

Poser Tim. 1 January, 2003. The Impact of Corporate Venture Capital: Potentials of Competitive Advantages for the Investing Company. Publisher: DUV. ISBN-13: 978-3824477760.

Shortell Stephen M, Zajac Edward J. 1988. Internal Corporate Joint Ventures: Development processes and performance outcomes. Strategic Management Journal. Volume 9. pp: 527-542.

Smith Sheryl Winston. September 2007. Strategic Venturing in the Global Medical Device Industry:Corporate Venture Capital and Entrepreneurial Clinician-Researchers. Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota.

Yip George S. 1982. Diversification Entry: Internal development versus acquisition. Strategic Management Journal. Volume 3. pp: 331-345.

Winters Terry E., Burfin Donald l. 1988. Venture Capital Investing For Corporate Development Objectives. Journal of Business Venturing. Volume 3. pp: 207-222.

Zajac Edward J, Golden Brain R. 1991. New organizational forms for enhancing innovation: The case of internal corporate joint ventures. Journal of Management Science. Volume 37. Issue 2. pp: 170-185.