Abstract

Nigeria has witnessed endless periods of volatile exchange rates. To date, the country has still not been able to stabilise its exchange rates, despite the growing importance of the Nigerian economy in Africa’s growth potential. Exchange rate fluctuations remain a very important macroeconomic concern among many economists in Nigeria because it largely explains how the Nigerian economy trades with other countries around the world. From this importance, this paper explores the causes of exchange rate fluctuations in the Nigerian economy. In this analysis, this paper highlights inflation, interest rates, current account balances, political instability, and terms of trade, as the main causes of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria. This paper also makes a special emphasis to investigate how the oil industry affects the Nigerian exchange rate and an insight into the scope (influence of the oil sector in the Nigeria economy) shows that this sector also affects exchange rates in Nigeria as well. This paper identifies these findings by undertaking multiple regression analyses. Inflation, interest rates, and current account deficits emerged as the main independent variables in the analyses, while exchange rate fluctuations emerged as the dependent variable. In sum, this paper proposes that the Nigerian economy should diversify from the overdependence on the oil sector to avoid the over-reliance on the oil sector as the main foreign exchange earner. Using oil revenue, this paper also proposes that the government should strive to invest more in other export sectors such as agriculture. This way, the Naira would be less dependent on the vulnerabilities of the oil sector and the rampant inflation that arises thereafter.

Introduction

Since the fall of the Bretton Woods system, economies have witnessed significant changes in their exchange rate regimes. The Bretton-Woods system was highly popular in the seventies, as it strived to stabilise international exchange rates through a negotiated agreement for the harmonisation of international monetary currencies (Bordo & Eichengreen 2007). The baseline currency for the system was the American dollar, but when the American government stopped the conversion of the dollar to Gold, the Bretton-Woods system lost its relevance in the international monetary system (Steil 2013). Nonetheless, the Bretton-Woods System had a significant impact on exchange rate volatilities in many countries, as it affected their exchange rates. Before divulging further into the details of the impact of this system, first, it is important to understand what exchange rates are.

Papaioannou (2006) defines exchange rates as the value that one currency would change to another. Since exchange rates are subject to different market forces, they change often. When people need more money to buy another currency, it is correct to say that the exchange rate is unfavourable, or has depreciated. The opposite is also true because if people require less money to buy another currency, the currency would be strong. When both situations prevail for too long, several macroeconomic problems may arise. For example, the rapid strengthening of a domestic currency may lead to current account problems. Such problems may arise because the currency may be overvalued. An overvalued currency may create an unfavourable balance of payments for a country because it makes it cheaper to import products, but expensive to export domestic products. This means that a very strong domestic currency would lead to more imports and less exports (unfavourable balance of payment).

Importers and exporters are therefore subject to exchange rate volatilities because a fluctuation in exchange rates directly affects their bottom-line operations. This situation is especially profound if the importers or exporters trade in huge volumes of goods or services. For instance, a local business that intends to set up a new plant in a country that does not produce the required machinery would budget for the importation of equipments from abroad. Through this activity, the new business would project its future expenditure in this regard. However, when there is a high rate of volatility in the exchange rate, the projected expenditure may increase, thereby affecting the projected expenditure of the business (Mordi 2006). A depreciation of the domestic currency, for example, would mean that the business has to import the equipments expensively. A distortion of these estimates would mean that the business’s profitability would decline because it would have experienced a higher cost of production (naturally, the business would pass the extra cost of importation to the customer, thereby increasing the cost of production). Based on the factors that affect exchange rates, exchange rate volatility emerges when the value of a currency fluctuates over a specified period. Exchange rate volatility may also symbolise the rate of deviation from a specified currency value (Mordi 2006). Here, when there are many parallel markets in an economy, the likelihood of exchange rate misalignment occurring is high (Dubas 2009).

Around the world, exchange rate volatilities have significantly affected the macroeconomic health of developing and developed economies alike. Its influence mainly stems from the ability of exchange rate volatilities to affect the realisation of macroeconomic objectives and goals. Economies with highly volatile exchange rates normally report unstable prices of goods and services and an intense uncertainty regarding macroeconomic outcomes (Bordo & Eichengreen 2007). Through such reports, economists have conducted several studies to investigate the impact of exchange rates on macroeconomic policies. They have found that exchange rates have a significant impact on a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the level of economic growth. In line with this view, many economists support the view that a misalignment of exchange rate policies may affect a country’s production (Dubas 2009). This distortion of the market is likely to have a significant impact on a country’s export in the short term and an equally strong impact on the overall economy in the end.

Exchange rates are therefore very important for predicting the economic health of a country because they are a critical component of the monetary policy framework (Bordo & Eichengreen 2007). However, more specifically, in today’s globalised society, exchange rates are also important in informing global investment strategies. Certainly, by studying exchange rate patterns, investors understand how to trade with their business partners. Such evaluations may inform their decision regarding whether to invest globally or domestically. In line with this discussion, the liberalisation of different markets and the expansion of the global market place (where different countries with different currencies trade among one another) compound the focus on exchange rates.

Based on the importance of exchange rates on the monetary policy framework of different countries, many developing countries desire a favourable exchange rate that would equate to low inflation and better terms of trade for local and foreign investors (Nnanna 2002). In this quest, many developing countries have strived to understand the causes of exchange rate fluctuations so that they can correctly align their economies to meet their fiscal and monetary objectives. In this analysis, it is crucial to mention that many factors determine exchange rates. The identification of these factors would easily help policymakers to adjust monetary and fiscal policies to achieve a favourable balance of payment (Ahamefule & Simbowale 2005). Through the adjustment of interest rates, policy makers would also have a significant impact on macroeconomic and microeconomic factors that affect their economies, such as, “inflation, price incentives, fiscal viability, competitiveness of exports, efficiency in resource allocation, international confidence and balance of payments equilibrium” (Ahamefule & Simbowale 2005, p. 1).

The efforts of such policymakers would exclusively try to predict future trends in exchange rate fluctuations. Despite the existence of several literatures regarding exchange rate causes, this area of study remains of great interest to many researchers because of the new global market and the different economic and political dynamics surrounding different regions of the world. Through this argument, Broadbent & Gill (2003) say that exchange rates do not simply denote the exchange value of one currency for another, but also the competitiveness of a country’s economy in the global market. Moreover, exchange rates stand out as reliable pillars for the sustenance of long-term macroeconomic policies of different economies. Through this analysis, it is correct to say that there is no single measure for establishing the causes of exchange rate fluctuations. Therefore, fluctuations in exchange rates and the exchange rate misalignments persist to be a serious economic and financial problem in a globalised society (Dubas 2009). Based on the realisation that exchange rate causes may be region-specific, this paper undertakes an ambitious study to investigate the causes of real exchange fluctuations in Nigeria.

Statement of the Problem

Unlike most economies in the eighties, the Nigerian government adopted a fixed exchange rate policy (Obi & Gobna 2010). Indeed, initially, the government of Nigeria evaluated its currency with the British pound. However, the central bank of Nigeria changed this measure and fixed the Naira (Nigerian currency) against the American dollar. In 1986, the fixed exchange rate policy was abolished and the Naira was allowed to fluctuate (subject to the forces of demand and supply) (Nnanna 2002). Albeit the government abolished the fixed exchange rate policy and adopted the fluctuating exchange rate, it adopted different measures to ensure the currency would be stable, even as it was subject to the forces of demand and supply. Obi & Gobna (2010) describes some of these policies as “Second-Tier Foreign Exchange Market (SFEM), Autonomous Foreign Exchange Market (AFEM), Inter-bank Foreign Exchange Market (IFEM), the enlarged Foreign Exchange Market (FEM), and the Dutch Auction System (DAS)” (p. 175).

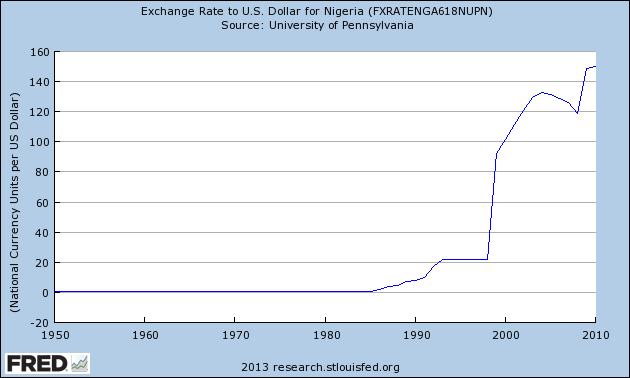

Before the introduction of the flexible exchange rate management strategy, the Nigerian government adopted the one-policy-at-a-time strategy to manage its exchange rate, but the ineffectiveness of this strategy led to the adoption of multiple policies to stabilise the Naira. Unfortunately, despite the adoption of these multiple policies, the Nigerian currency failed to stabilise. Instead, the Naira significantly depreciated against the US dollar. The diagram below shows the effect of the fixed Naira and its subsequent slide after the adoption of a flexible exchange rate policy.

According to the diagram above, before the Naira depreciated, its relative strength against the dollar was relatively admirable in the late seventies and early eighties. To explain this situation, Obi & Gobna (2010) say in the sixties, seventies, and early eighties, the Naira was very stable against the US dollar because of the fixed exchange rate. Contrary to the opinions of many analysts, the adoption of the flexible exchange rate regime saw the Naira significantly depreciate against the dollar. In fact, as described in the diagram above, the depreciation of the Naira has been ongoing, even in the last decade. To explain the progress of this depreciation trend, Obi & Gobna (2010) say, the depreciation continued for most parts of the nineties (although relatively slow). The last decade has also seen the Naira significantly depreciate against the dollar. For example, Obi & Gobna (2010) say, “the Naira depreciated further to N102.1052, N120.9702, and N133.5004 in 2002, 2003, 2004; respectively” (p. 178). In 2009, the same trend continued as the Naira further depreciated to N170 against the US dollar.

The depreciating Naira and the unstable exchange rates in Nigeria create a lot of instability in the Nigerian economy. More specifically, the sliding value of the Nigerian currency creates an unstable economic environment for new and existing businesses to operate. A favourable exchange rate would therefore be more desirable for importers and exporters alike. However, the creation of this favourable business environment largely lies in understanding the causes of exchange rate fluctuations in the oil-rich nation. In this regard, Nigeria is an interesting economy to study because the country’s economy is different from other types of economies in Africa. For instance, unlike other African countries that are import-oriented, Nigeria is export-oriented. The export-oriented nature of the economy also holds unique dynamics that differentiate Nigeria from other export-oriented countries in the west (and in Asia) because the Nigerian economy is mainly monolithic (Ogbechie & Koufopoulos 2009). In other words, the country’s exports mainly concentrate on the energy sector (oil). Another interesting dynamic about the Nigerian economy is that, while the country is dependent on its oil exports, most other aspects of the country’s economic dynamics resemble other developing nations. For example, by virtue of being a developing nation, other sectors of the Nigerian economy rely on imports. At the same time, according to 2012 economic findings, Nigeria remains among Africa’s bustling economies, with an impressive growth rate of about 6% (yearly average) (Steil 2013). Lastly, unlike western countries, Nigeria is unique because its economy is vulnerable to political instability. For example, the latest wave of terrorism activities in the West African country has affected the Nigerian economy in a negative way (the most notable effect being the negative international press that the attacks have brought). Indeed, many investors are wary of investing in the region because of political unrests and religious conflicts, mostly in the Northern part of the country (fuelling the terrorist activities). The influence of extremist movements, the over-dependence on oil, the positive economic forecast, and the import-oriented non-oil sector of the Nigerian economy make it an interesting country to analyse.

In the formulation of the research objectives of this paper, this study acknowledges that many researchers have explored the causes of exchange rate fluctuations in modern economies. Key findings of their analysis have shown that Inflation, current-account deficits, and interest rates emerge as common causes of exchange rate fluctuations. However, most of these researchers have mentioned these factors in unrelated economic contexts. Therefore, this study sought to focus on these common economic factors in the Nigerian context and understand how they interplay with the unique macroeconomic factors of the Nigerian economy (as mentioned above) in affecting the exchange rates of the oil-based economy.

Research Aim

- To establish the causes of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria

Research Objectives

- To explore the extent that political instability affects the Nigerian exchange rate

- To establish the impact of the Nigerian oil industry on the exchange rate regime of the country

- To investigate if current-account deficits determine exchange rates in Nigeria

- To find out if inflation determines Nigeria’s exchange rates

- To establish the extents that interest rates affect the volatility of the Nigerian exchange rates

Structure of the Paper

The structure of this paper outlines six chapters. The first chapter is the introductory chapter, which explains the research topic and expounds on the direction of the research. The second chapter is the literature review, which explores and evaluates what other researchers have said about this research topic. The third chapter is the methodology chapter, which explains how I conducted the research. The outcome of the methodology section appears in the fourth chapter – findings. However, discussions of the same contents outline the fifth chapter. The last chapter is the conclusion and recommendations chapter, which summarises the main points of the study and possible areas of future research.

Literature Review

The first chapter of this dissertation already shows that the impact of exchange rate volatilities and misalignments are very important in understanding the macroeconomic health of any given economy. However, recent advancements in theory and practice regarding exchange rate volatilities have created new attention on the subject (Horne 2004). For example, advancements in econometric studies have increased the volume of reliable data regarding the causes of exchange rate fluctuations. Many researchers have therefore used such developments to improve their findings (Ogbechie & Koufopoulos 2009). More specifically, advancements in Econometrics and associated areas of studies have helped to expound on country-specific details about exchange rate volatility.

Nigeria is one such country that commands a lot of attention in this regard because the West African country has been able to use its exchange rates to determine how it trades with other countries (within Africa and the rest of the world). Some economists have advanced several reasons for the depreciation of Nigeria’s currency, but most of them attribute this trend to the decline of foreign exchange reserves in Nigeria (Ogbechie & Koufopoulos 2009; Abeysinghe & Yeok 1998; Omojimite & Oriavwote 2012). A small section of analysts say the fall of the Naira largely traces to speculative activities by major economic players like banks (Horne 2004; Quang 2008). For example, some analysts have criticised some banks for having an abnormal quest to make profits during the recent global financial downturn. These analysts have accused such banks of round tripping (Quang 2008). Round tripping involves an illegal action by Nigerian commercial banks to buy foreign exchange from the country’s central bank and sell them to parallel market operators at different prices (from the purchase price) to make a quick profit. The boom in the parallel exchange rate market started when there was a huge demand for foreign currencies (through a high demand for dollars by importers) and the overregulation of official foreign exchange agencies (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). This situation forced many importers to look for foreign exchange through the existing parallel markets. Some analysts view such operations to have exacerbated the problem of exchange rate fluctuation in the West African state (Omojimite & Oriavwote 2012).

Nonetheless, studies that investigate the causes of real exchange fluctuations in Nigeria trace back to the late seventies and early eighties when many researchers advanced different models for predicting exchange rate fluctuations (Omojimite & Oriavwote 2012). Some researchers concentrated on developing a reliable model for establishing the causes of real exchange fluctuations for developing countries. For example, Obadan (1994) used a sample of about 12 developing countries to come up with the random walk model. In his analysis, he showed that real exchange rate is a function of the “terms of trade, government consumption, capital controls, exchange controls, technical progress, domestic credit, real growth, nominal devaluation” (p. 151). The study also established that, in the end, only real exchange rate variations have the ability of affecting the real exchange variables of a country. Although this finding applied to most developing economies like Nigeria, Obadan (1994) formulated a more specific model that would explain the causes of real exchange rate fluctuations in Nigeria. Obadan (1994) also used the random walk model for predicting the real exchange rate to come up with a more comprehensive model for predicting real exchange variables by introducing a two-stage least square regression analysis into his model. Unlike other studies that emphasised on the long-term real exchange variables, as the main influences of real exchange variables, Obadan (1994) found that, in the Nigerian context, structural and short-term factors played an instrumental role in adjusting the country’s real exchange rates.

Similar to the studies undertaken by Obadan (1994), Udousung & Umoh (2012) conducted a similar study in Zambia to investigate the real causes of exchange rate fluctuations in the South African country. They conducted this study in reference to the causes of real exchange rates as a function of “terms of trade, capital inflow, the closeness of the economy, and excess supply of domestic credit” (Udousung & Umoh 2012, pp. 22). After using the co-integration technique, as an analytical tool in their analysis, Udousung & Umoh (2012) established an equilibrium relationship between Zambia’s real exchange rate and the causes of exchange rate volatilities.

These findings are parallel to similar studies conducted by Obadan (1994), which aimed to investigate the impact of the real exchange rate in the non-oil sector of the West African economy. Specifically, his findings aimed to explore how real exchange rate misalignment and volatility affected this sector. In this analysis, Obadan (1994) also used the purchasing power parity model to understand this relationship. Here, Obadan (1994) found out that exchange rate misalignment and volatility significantly affected the growth of the country’s non-energy sector.

Studies that have significantly worked to explore the causes of real exchange rate fluctuations in Nigeria have done so in oblivion of the long-term effect of the macroeconomic data used (Omotoye & Sharma 2006; Obadan 1994). These studies also differ from recent studies that investigate the same phenomenon because they relied on traditional models of real exchange determination, such as the two-stage least square method. Few researchers who conducted such studies also rarely incorporated the macroeconomic intrigues that prevailed after the introduction of the structural adjustment program (SAP). From these flaws, researchers who have conducted more studies (that are recent) have tried to incorporate the co-integration technique to address some of these oversights (Udousung & Umoh 2012). Their studies have therefore analysed the causes of exchange rate fluctuations across a long time, such as four decades, in total. One significant area of great differential, between past and present researchers, is the inclusion of price levels in the analysis of causes of exchange rate fluctuations (in recent studies) (Udousung & Umoh 2012).

Exchange Rate Policy in Nigeria

The Nigerian government has been proactive in trying to stabilise the country’s exchange rates. To this extent, the government has adopted both fixed and flexible tools for stabilising the exchange rates. These efforts have however been undermined by significant social-political instabilities such as the Nigerian civil war that occurred in the sixties and seventies and fluctuations in oil price. However, studies that have investigated the causes of exchange rate volatility in Nigeria have focused largely on the macroeconomic factors that affect movements in exchange rates (Dubas 2009; Abeysinghe & Yeok 1998). Most of the studies conducted by previous researchers largely divide into two main categories. One category of researchers focused on the balance of payment overvaluations, while another group of researchers support the devaluation of the exchange rate (Dubas 2009; Abeysinghe & Yeok 1998). Researchers who support overvaluation of exchange rates include Dubas (2009) and Abeysinghe & Yeok (1998) (among others). Researchers who support the depreciation of currency include Sanni (2006) and Obaseki (1991) (among others). Sanni (2006) and Obaseki (1991) have especially done parallel studies, which show that there are common factors that affect exchange rate fluctuations in developing countries. Some of these factors include unfavourable terms of trade and poor balance of payments. The over-valuation of currencies is also a primary reason for the high exchange rate fluctuations in Nigeria and other developing countries (Cheung & Chinn 2007). Cheung & Chinn (2007) especially says that the overvaluation of the currency (which was a common feature of Nigeria’s economic history) further exacerbates the problem of unfavourable balance of payments because it distorts current and capital accounts.

Through the above lens of analysis, Umoru & Odjegba (2013) say that the flexing of exchange rate controls therefore emerges as an important control for creating a favourable balance of payment because of its effect on current and capital accounts. Stated differently, the flexing of exchange control is an effective method for controlling economic disequilibrium (especially concerning imports and exports). For example, the devaluation of the Naira is an effective way of increasing the country’s level of exports, thereby creating a favourable balance of payment. This logic informs why some of the researchers mentioned above favoured the devaluation of the Naira to support exports. Dufrenot & Yehoue (2005) have also supported this opinion by asserting that currency devaluation helps to remedy finance deficits. Umoru & Odjegba (2013) add, “Devaluation results suggest improvements in the reserve position of the devaluing countries. Here, reserve position improvements amount to an improvement on the balance of payment position” (p. 265).

The adoption of the fixed exchange rate stems from several control factors, but these controls largely aimed to adopt strict controls and regulations in the exchange rate regime. The adoption of these strict regulations however did a lot of damage to the Nigerian economy as it promoted the importation of finished goods, thereby killing domestic industries that were supposed to produce the same goods. Moreover, Okike (2004) says the adoption of the fixed exchange rate policy led to the overvaluation of the Naira. This situation led to imbalances in external reserves, thereby creating an unfavourable balance of payment.

The shift from the fixed exchange rate policy changed in the eighties when Nigeria witnessed a change in the fortunes of the Naira, as it appreciated considerably because of its oil exports. This situation only prevailed for a short while, before the end of the oil boom, which heralded the introduction of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) -recommended structural adjustment program (SAP), which required the Nigerian government to allow market forces to determine the exchange rates (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). Despite the introduction of this market-oriented exchange rate system, the Naira depreciated further in the eighties. This depreciation led to a lot of concern among economists and policymakers regarding the high volatility of the Naira (Okike 2004). The table below shows the fluctuations of exchange rates in Nigeria over the past three decades.

The diagram above highlights different issues that help in understanding the volatility of the Nigerian currency including the period, nominal exchange rate, nominal effective exchange rate, nominal exchange rate premium, the effective exchange rate, and the parallel market exchange rate. Noticeably, what manifests from the above evaluation is the huge difference between the official and market exchange rates. This disparity shows many market distortions and regime influences that explain the wide disparities in official and real exchange rates. For example, Mayowa & Olushola (2013) explain that during 1994-1998, there was a lot of government influence in fixing the country’s exchange rates. The activities of the Abacha (former president of Nigeria) regime largely fuelled most of these artificial influences on exchange rate determination (Mayowa & Olushola 2013).

The influence of the Abacha regime in artificially influencing the exchange rate highlights a common finding by most researchers that regime policies have largely influenced the Nigerian exchange rate (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). For example, in the late sixties and early seventies, the real exchange rate fluctuations were only about 4% (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). Surprisingly, this figure sharply rose to about 35% in the late nineties and early 2000s. This high real exchange volatility showed that Nigeria reported among the highest real exchange volatilities in the developing world. Mayowa & Olushola (2013) explain that the wide deviation in real exchange rates started to occur when there were numerous government interventions to stabilise the exchange rate. Other factors that played a role in fuelling these phenomena were the inflow of oil revenues into the Nigerian economy, high inflation rates, and real exchange rate uncertainty (which prevented the inflow of foreign money through limited foreign investments).

Concerning the high volatility of the Naira, Mayowa & Olushola (2013) say the main arguments that arise in the analysis of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria is the overvaluation of the Naira and the monopoly of the Nigerian government in holding foreign exchange reserves. From such concerns, the stability of the Nigerian exchange rate has been a key goal of the government because the central bank of Nigeria is committed to creating a positive public perception of the economy (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). Stated differently, if people see that the exchange rate is weakening, they develop the opinion that the economy is generally weak.

The prevention of real exchange over-evaluation has dogged many policymakers in Nigeria because the government is the main source of foreign exchange reserves in the country (Nnanna 2002). The central bank is one government institution that has also tried to weigh in on this issue by managing foreign exchange rates through the management of foreign exchange floats. For example, in the late nineties, the central bank embarked on an ambitious effort to sell foreign exchange reserves through the inter-bank market (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). In this market, the banks freely traded foreign exchange through negotiated rates. Bureau de Change and parallel markets for foreign exchange also formed part of this market. The effort by the central bank to stabilise the exchange rate however flopped as the exchange rate significantly depreciated to about N101.65 to the US dollar (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). A high demand for foreign exchange by importers (a high government spending occasioned this) contributed to this inflation. For example, in 2000, the demand for foreign exchange rose from about $5 billion to about $7 billion (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). Parallel foreign exchange markets also depreciated in similar fashion, thereby causing a foreign exchange crisis in April 2001. During the crisis, the government offloaded most of its foreign exchange reserves into the market to stabilise the Naira. This move helped to improve the value of the Naira by moving it from a low of N140 to N133 (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). The introduction of excess foreign exchange reserves into the market was further followed by the introduction of the Dutch Auction System (DAS) which further appreciated the value of the Naira to about N128, in the year 2006 (Mayowa & Olushola 2013). After the introduction of these measures, the Naira was relatively stable for the next two years. In the year 2008, the Nigerian economy received a significant increase in foreign exchange reserves, thereby improving the government’s reserve level of foreign exchange. Overall, the exchange volatilities show that the exchange rate regime may continue to be important for the overall well-being of the Nigerian economy. Economists have used different models and hypotheses to explain the volatilities of the Nigerian exchange rate by investigating the underlying macroeconomic conditions and theories that inform this relationship. The Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis, fundamental equilibrium exchange rate (FEER) model, and purchasing power parity models are examples of commonly used frameworks for explaining the causes of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria.

Purchasing Power Parity

Economists have not only used the model of purchasing power parity to explain exchange rate fluctuations, but also to explain other macroeconomic issues as well (Quang 2008). This model outlines that adjusting the prices of local and foreign products should offset imbalances and sporadic shifts in exchange rates (Horne 2004). This understanding therefore suggests that even though the purchasing power parity of an economy may remain the same, shifts in domestic and international prices should offset any volatility in the exchange rate. Few empirical studies have affirmed this model and the few that do, show minimal adjustments in exchange rate values (Sjölander 2007). Some researchers have advanced several issues, like sticky labour prices and market hurdles, to explain the little convergence of exchange rates (to normal levels). Since these market rigidities are difficult to eliminate, Li & Lin (2008) suggest that market innovations are the best way for economies to achieve a favourable outcome, regarding purchasing power parity. Such kinds of analyses are often common when there is a high inflation in the economy because such conditions normally lead to severe price uncertainty (deviation from purchasing power parity).

Albeit inflation is a key factor to consider in this analysis, it is among many factors that affect exchange rate volatilities. For example, other factors that affect exchange rate volatilities include movements in interest rates, flow of foreign money, and inflation (among other factors) (Quang 2008). The economic condition of any given country determines the influence of these factors on the volatility of its exchange rates. These factors are likely to affect developing economies like Nigeria because such economies are usually transiting to become developed and stable. Since deviations from the purchasing power parity stand at the centre of understanding interest rate fluctuations, many researchers have conducted parallel studies to test purchasing power parity deviations (as an attempt to use the model as a permanent fixture for predicting exchange rate volatilities). Hyrina & Serletis (2010) say the effectiveness of this model largely depends on the influence of the exchange rate factors on monetary policies. Researchers like Balasa (1994) and Obstfeld (1993) have investigated economic factors that affect productivity differentials and found out that these factors have a significant impact on the ability of the purchasing power parity model to predict future exchange rate volatilities. Chinn & Johnston (1996) have also led a team of other researchers to evaluate the impact of real interest rates on exchange rate volatilities and said, just like productivity differentials; real interest rates also affect exchange rate volatilities. Exogenous factors, like the volumes of imports and exports also have the same impact on exchange rate volatilities. Nonetheless, based on the macroeconomic factors that affect exchange rate fluctuations, there is a consensus among several researchers that macroeconomic fundamentals largely affect long-term and medium term exchange rates (Balasa 1994; Obstfeld 1993; Chinn & Johnston 1996). Through this view, the fundamental equilibrium exchange rate (FEER) model emerged.

Fundamental Equilibrium Exchange Rate (FEER) Model

Many economists have used the FEER model to establish fundamental equilibrium real exchange rates (Omotoye & Sharma 2006; Obstfeld 1993; Chinn & Johnston 1996). They have done so by evaluating the impact of internal and external macroeconomic factors of exchange rate fluctuations (Omotoye & Sharma 2006). An internal balance manifests when there is little or no unemployment, or inflation, levels. An external balance manifests when a country experiences a favourable balance of payment and very minimal (or no) national debts (Omotoye & Sharma 2006). The fundamental equilibrium exchange rate model therefore seeks to evaluate the impact of these market forces (sometimes speculative) and assessing how they affect the overall balance of exchange rates.

Balassa-Samuelson Hypothesis

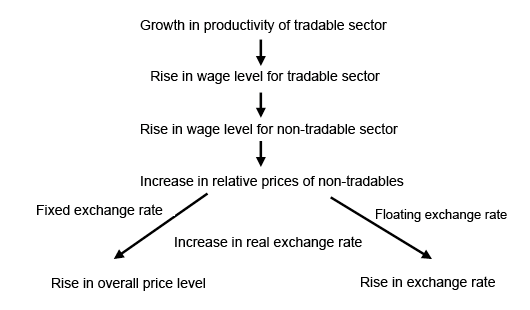

To understand the factors that determine real exchange fluctuations in Nigeria, Omojimite & Oriavwote (2012) explored the impact of Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis in the Nigerian context. The Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis stipulates that wealthy countries have a higher price index because of their high per capita income, while the opposite is true for poor countries because the model outlines that poor countries tend to have a low price index because of their low per capita income. For example, Johnstone (2011) says that emerging economies tend to have a high inflation rate compared to developed economies. This fact has emerged in several economic debates that strive to predict when the economy of China may surpass the US economy, as the largest economy in the world. Within, this debate, experts have established that there is a high inflation rate in China (4%) compared to the US (2%) because China is a developing economy (Johnstone 2011). This finding only reinforces the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis, which outlines that emerging economies tend to have a higher rate of inflation than developed economies. Some analysts have explained this relationship by analysing growth in the tradable and non-tradable sectors (Johnstone 2011). The model below explains this relationship

According to the figure above, there is a high emphasis on the tradable sector as the most defining factor for real exchange fluctuations. The diagram above shows that a high growth in the productivity of the tradable sector is likely to have a ripple effect of a rise in the wage labour for the tradable and non-tradable sectors. This process is likely to have a significant impact on the non-tradable sector as well (by increasing the relative price of goods in this sector). This eventuality will likely have an impact on the exchange rates (both floating and fixed exchange rates) by increasing it as well. Consequently, there would be a rise in the overall price level and real exchange rate as the Balassa-Samuelson Effect dictates.

The above model hinges on the premise that production tends to vary more in the trade sector because productivity is among the greatest determinant of real exchange rate. The Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis also outlines that most industries, which tend to export more goods (compared to other sectors of the economy) attract most investments (thereby attracting more foreign funds). When Omojimite & Oriavwote (2012) established the effect of this model in the Nigerian analysis, they established that the Balassa-Samuelson Effect is true in the determination of the Nigerian real exchange rate. Similarly, through the adoption of the Johansen Co-integration Test, the researchers also suggested the existence of a long run relationship among “technological productivity, foreign private investment, the ratio of government expenditure to GDP and the effective exchange rate” (Omojimite & Oriavwote 2012, p. 127). Despite the accuracy of the above models and theories in explaining the causes of exchange rate in Nigeria, unconventional factors, like the reliance on oil industry and political instabilities, have rarely featured on the empirical analyses of exchange rate fluctuations in Nigeria. These factors outline below

Political Stability and Exchange Rates in Nigeria

Many researchers have shown that political risk is a key determinant of exchange rates (Guièze 2012; Online Forex 2013). For example, the political risk may significantly affect investor perception of a country, especially how safe it is to invest in such a country. When there is a significant political risk, investors are likely to perceive the host country as an unstable economy, thereby creating a depreciation pressure on the domestic currency. One key factor that influences investor perception of a country is political unrest because it causes a lot of uncertainty in the economy, especially regarding the future of investments. For instance, political uncertainty makes it very difficult for analysts to estimate the value of foreign investments in the end. The main logic here stems from the difficulty in estimating the future of investments in a country that has an unstable future. This uncertainty also closely relates to a bigger problem of failing to understand how future macroeconomic policies may look like in the future. Countries that have such types of concern normally pay for such uncertainties through fluctuations in exchange rates (Guièze 2012).

Nigeria has witnessed several periods of political instability. As a result, some people see the country as a politically risky nation, more specifically because its political problems associate with poor infrastructure, and mismanagement of the economy. Rampant corruption has also been a key concern among many investors (Guièze 2012). The tide only changed in 2008 when the Nigerian government embarked on ambitious efforts to restore the image of the country in this regard. A significant task for recent regimes has been to shift the economy from being overly dependent on the oil sector (an issue that past military rulers failed to address). At this point, it is important to say that the oil sector accounted for more than 90% of the government’s foreign exchange sources (Usman 2009). Oil revenue also accounted for about 80% of the government’s revenue source (Usman 2009).

Some observers also accuse the Nigerian government of having no political will to improve the business climate (by eliminating political issues that affect the global perception of the economy, such as rampant corruption) (Guièze 2012). A 2013 report by the World Bank has said rampant corruption is the greatest cause of the poor global perception of Nigeria as an attractive investment hub because Nigeria ranks 131/185 in the global corruption index (Online Forex 2013). Although this ranking elevates Nigeria above the average corruption level of sub-Saharan Africa, this poor ranking has done a lot of damage to the country’s global perception as an attractive investment destination. More damage has occurred through a downward pressure on the exchange rate value.

Besides the level of corruption in the West African country, recent rankings of governance and political risk in Nigeria show that the country is not faring well, in terms of governance and political risk management (Guièze 2012). In fact, Guièze (2012) says, “Nigeria ranks among the worst in the world in the World Bank’s governance survey” (p. 27). This poor ranking has largely been characteristic of the Nigerian economy for a long time because Guièze (2012) says that only marginal improvements in the level of governance have occurred in the late nineties. Therefore, for a long time, poor governance standards in Nigeria have largely remained the same over the past decades. A survey to evaluate the political stability of 213 countries around the world showed that Nigeria was among the most politically unstable economies in the world (Guièze 2012). In fact, in the study, only 4% of all the countries sampled presented a worse political risk than Nigeria (Guièze 2012). For example, many religious and ethnic tensions have characterized the oil-based economy in the past few years. The increase in religious attacks by the extremist movement, Boko Haram, only highlights a tip of the iceberg regarding the political risk in Nigeria (the years 2011 and 2012 registered the highest number of attacks by this group). Other extremist movements are active in Niger, thereby causing further political instability in the country. These issues have been a source of political risk for the country. Consequently, their effects have drastically affected the economy and the exchange rate of the Naira, viz-a-viz other currencies. For example, activities of rebel groups in Niger have affected oil production in Nigeria, thereby disrupting the export of oil from Nigeria. This situation has led to a decline in oil revenue (a key foreign exchange earner in the oil-based economy).

Political risk therefore emerges as an undesirable force that negatively affects the value of the domestic currency. In this analysis, ideal situations emerge when currencies are neutral to political intrigues. When countries achieve this desired level of neutrality, investors deem their currencies as “safe havens.” The US dollar and the Swiss Franc are perfect examples of “safe” currencies. This is why they are widely used across the globe. In fact, Online Forex (2013) says that the US dollar (for example) has withstood a lot of political and military turmoil, such that it even appreciates when there is a high political risk in the economy. The stability of such currencies therefore emerges as a desirable quality for most investors. However, people should understand that the “safety” of such currencies do not stem from the strength of the currencies, but rather, from their neutrality to political forces. Nigeria should borrow a leaf from the stability of such currencies, not by making the Naira neutral to political forces, but by avoiding political turmoil altogether. The vulnerability of the Nigerian currency to political turmoil is however not unique to the West African state because other countries also share the same fortune. For example, Online Forex (2013) says, Zimbabwe, Israel, Thailand, Pakistan, and Russia (among other countries) also exhibit a high level of vulnerability to political risk. Comparatively, besides the Swiss franc and the US dollar (as mentioned above), the Australian dollar, Japanese yen, and the European Euro (among others) are also stable currencies (Forex 2013).

Oil Sector

It is difficult to ignore the impact of the oil sector in determining the exchange rates of the Nigerian economy because analysts estimate that Nigeria’s oil production is the greatest in Africa and the 10th greatest in the world (Al-mulali & Normee 2012). Indeed, with a production capacity that transcends 2,000,000 barrels a day, it is naive to assume that the intrigues of the oil sector do not affect the exchange rate volatility of the West African country (Al-mulali & Normee 2012). A key concern for the intrigues of the oil sector in the Nigerian economy is its heavy influence on the country’s balance of payment and GDP growth.

The diagram below shows how Nigeria’s GDP growth tightly pegs to the movements in the oil sector:

According to the diagram above, since the discovery of oil in Nigeria, its GDP growth has been heavily dependent on the intrigues of the oil sector. For close to four decades now, this trend has prevailed. Ironically, although the huge exports of oil from Nigeria aim to improve the country’s balance of payments, the same oil sector works against this outcome by increasing the country’s import bill through the importation of refined oil. The domestic consumption of refined oil occurs because Nigeria lacks stable refineries that would meet the domestic demand for refined oil. The impact of the oil sector in affecting the country’s balance of payments therefore has a significant impact on the country’s exchange rates.

From the above intrigues, many economists and researchers have been preoccupied with understanding the effect of the oil sector in influencing the exchange rate of the West African economy because they acknowledge that the oil sector is an important export for Nigeria (Al-mulali & Normee 2012; Usman 2009). The support of a depreciated Naira on the export sector is the basic principle that guides such studies. Through the same lens of analysis, the appreciation of the Naira would easily discourage exports and encourage the growth of the import sector. To support this claim, Usman (2009) says, “exchange rate depreciation leads to income transfer from importing countries to exporting countries through a shift in the terms of trade, and this affects the economic growth of both importing and exporting nations” (p. 1). Nonetheless, Usman (2009) provides a very comprehensive understanding of the impact of the oil sector on the Nigerian exchange rate by saying that the influence of the oil sector on the country’s exchange rate is indirect (contrary to the opinions of many people). Specifically, Usman (2009) says that the impact of the oil sector on the country’s exchange rate would not be as direct as the impact of macroeconomic policies on exchange rates. One notable finding about Usman (2009) is the understanding that most spikes in the oil industry harm the economy.

McKillop (2004) supports this view by saying that “higher oil prices reduce economic growth, generate stock exchange panics, and produce inflation, which eventually lead to monetary and financial instability” (p. 2). The same outcome would manifest in economies that have a high interest rate, thereby causing further real exchange volatility, or in worst-case scenarios, recessions. Similar findings have emerged in the works of Jin (2008), which show that an increase in oil prices would cause a lot of exchange rate volatility, thereby leading to slow economic growths.

The effect of the oil sector on the Nigeria economy manifests best in the last decade when the global prices of oil sharply increased. Relative to this assertion, Al-mulali & Normee (2012) explain, “From the year 2003 to 2010, oil prices began to increase rapidly reaching phenomenal levels of US$140/b in 2008 and reduced to US$41/b in 2009 because of the global financial crisis, and starting to increase again to US$91/b in 2010” (p. 375). The fluctuations of oil prices had a significant impact on the GDP of Nigeria, but more specifically, these fluctuations tested the ability of the Naira in absorbing the movements of oil prices (McGuirk 1983). The effect of movements in the oil price is not only a special issue in Nigeria because other researchers have found out that similar oil-producing countries have experienced a similar fate. For example, Amano and Norden (1995) said that the movements in oil prices always affect the stability of the US dollar. Abdelaziz & Chortareas (2008) also express similar views when they said that the movements in global oil prices also affect the real exchange rate stability of oil-based economies in the Middle East, such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. Similar movements in global oil prices have also significantly affected the real exchange rate stability of the Russian currency (although the diversification of the Russian economy has helped to counter this effect) (Abdelaziz & Chortareas 2008). The exception to this rule has been the Chinese economy, which did not report significant fluctuations in its exchange rates, despite the volatile movements of global oil prices. Al-mulali & Normee (2012) say, mainly, the versatility of the Chinese currency depends on its minimal dependency on oil exports. Similarly, the Chinese currency pegs its strength to the performance of other currencies. Al-mulali & Normee (2012) add,

“In the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries, which are under the flexible exchange rate regime, oil prices cause depreciation of their real exchange rate in the short run. On the other hand, the countries that are under a fixed exchange rate regime do not only experience an appreciation of their real exchange rate but also suffer from higher inflation than the countries with flexible exchange rates” (p. 376).

The Dominican Republic also provides another classic example of how movements in oil prices affect real exchange movements because an increase in the oil prices caused a depreciation of its real exchange currency (the government had to buy many dollars to buy oil, thereby causing a devaluation of its local currency) (Al-mulali & Normee 2012). Besides, then Dominican republic, Tsen (2011) found that, “oil prices comprise the main causes of real exchange rate movements in Japan, South Korea, and Hong Kong” (p. 800) as well. Some oil-producing nations do not identify movements in oil prices as the main causes of real exchange rate volatilities, but rather, the inconsistencies in oil production as the causes of real exchange rate movements (Al-mulali & Normee 2012). Saudi Arabia is one such economy where production shocks affect the country’s real exchange rate, more than movements in oil prices.

In related studies, Tsen (2011) investigated the impact of oil price fluctuations across 12 oil-based economies (including Nigeria) and established that there is a long-term relationship between fluctuations in oil prices and real exchange volatility. In this analysis, the independent variable was oil prices, while the dependent variable was real exchange rates. In the same analysis, Tsen (2011) also included the effects of inflation and government spending in assessing the impact of oil prices on exchange rates. Here, he established a commonly cited finding, which shows that high inflation rates cause a depreciation of the exchange rate (Al-mulali & Normee 2012). He also established that a country’s GDP (based on the purchasing power parity) has a significant effect on the exchange rate (a positive effect) (Tsen 2011). Lastly, Tsen (2011) identified a negative correlation between government spending and current account deficits on real exchange rates. Nonetheless, through the impact of oil price fluctuations on exchange rates, Tsen (2011) proposed that oil-based economies, like Nigeria, should use flexible exchange rate regimes to manage their exchange rates better. The flexible exchange rate regimes would therefore provide a better shock absorber for fluctuations in exchange rates, thereby stabilising the economy (by extension). From these analyses, the impact of the oil sector is a significant determinant of real exchange In Nigeria, as is the case in many G7 countries (Chen & Chen, 2007).

Methodology

Research Design

The main research design of this paper is the quantitative research design. The quantitative research design is appropriate for this paper because the study mainly uses macroeconomic data to answer the research findings. The adoption of this technique was appropriate for this paper because it gave room for measuring and analysing data. This advantage was especially important because of its ability to provide a more reliable basis for studying all the independent and dependent variables in better detail. This provision helped to introduce a sense of objectivity in conducting the research. Moreover, this advantage made it more possible for the researcher to test the hypothesis (easily), as the quantitative research design provided an opportunity to test the available statistics in better detail. The main drawback to using the quantitative research is its failure to provide a more contextual understanding of the research findings, as it fails to provide the meanings behind the statistics as touted in this paper (as the qualitative research design would).

Data Collection

The main data collection method for this paper was secondary research sources. In other words, this paper largely relied on the findings of other researchers, government statistics, and economic data. Journals, books, and national economic data were the main sources of secondary research. The data collection process sufficed in this regard because of the lack of reliable connections to conduct a primary research. Stated differently, no reliable research sources or connections to individuals, who were adequately knowledgeable about the Nigerian economy and the causes of real exchange rate volatilities, existed. To this extent of the analysis, the findings of this paper provide a deduction of economic statistics.

Data Analysis

The data analysis process for this paper stemmed from a collection of different regression analyses and the application of the grounded theory. The grounded theory outlines that the research findings should stem from the collection of information that would be gathered by adhering to four critical stages of data analysis – coding, conceptualising, categorising, and developing the theory (Glaser 2009). Through the grounded data analysis method, the data analysis process started from the collection of research information and ended in the production of the research findings. Proper data collection, transcription, and indexing of the research data outlined the progression through the different stages of the data analysis process. The initial step of the data collection process started with the sourcing and collection of research information. The initial data collection process included piecing together information that appeared relevant for the research (for easy referencing). This process happened after sieving through numerous volumes of data and picking the researches that were interesting, relevant, and important to the research topic. Subsequently, a series of data, which bore different codes, emerged. The codes symbolised the relevance to a specific subject area of interest. Since the grounded data analysis process is a very dynamic process, the data analysis process continued throughout the collection of secondary sources (Glaser 2009). Throughout this process, some codes and concepts were added and subtracted during the formulation of relevant themes, depending on how the research shaped up and how I understood the research topics. The main themes of the data analysis process aimed to explain the research topic by focusing on the five most important areas of analysis – interest rates, inflation, current account deficits, oil industry dynamics, and political stability.

Through the adoption of the constant comparison analysis, the codes and concepts were refined in three stages, which involved evaluating the indexing system, writing memos (to jot down important points), and the integration of related themes. The product of this process was the emergence of critical themes of analysis (interest rates, inflation, current account deficits, oil industry dynamics, and political stability) that resonated with the research objectives. Similarly, the production of a list of memos, the production of numerous theoretical memos, suggestions of possible linkages, and the production of relevant models that would frame the pieces of information into understandable texts are some of the issues that emerged here. In sum, the grounded theory helped to ease the data analysis process by outlining different stages of analysing researcher, including the evaluation of theoretical sensitivity, adhering to three steps of analysis (open coding, axial coding, and selective coding), theoretical saturation, and the development of a workable theory that summed up the research findings. The adherence to these stages paved the way for the adoption of regression analyses.

Since the aim of this paper was simplistic in evaluating the causes of exchange rate fluctuations in Nigeria, this paper used a single-equation model in the regression analyses. This model comprised of four independent variables (interest rates, inflation, capital account balances, and terms of trade). The dependent variable was the exchange rate. The paper used multiple regression analysis to understand the relationships between the explanatory variables (independent variables) and the exchange rate (dependent variable) through two methods of estimating coefficients of this economic relationship – single equation method and simultaneous equation method.

The single equation and simultaneous equation methods differ from one another because the latter applies to several equations at the same time, while the single equation method only applies to one analysis at a time. Classic examples of single equation techniques include ordinary least squares technique, and classical least square techniques (Udousung & Umoh 2012). Examples of simultaneous equation methods include three-stage least squares and full information maximum techniques (Udousung & Umoh 2012). The ordinary least square technique was appropriate for this paper because the research question aimed to study a simple phenomenon. The ordinary least square technique was also appropriate for this paper because it denotes a single equation technique that was appropriate for the evaluation of a simple phenomenon (Bolaji 2012). The simplicity of the ordinary least square method in computation also made it more attractive for this paper. For example, the ordinary least square method does not require many data when computing. It is also cheaper and less time consuming to use. Furthermore, it is easy to understand the mechanics of this technique, thereby posing a high applicability level in econometric research. Besides, the ordinary least square technique is a key technique in econometric studies. For example, many econometric techniques use this method in their applications (Udousung & Umoh 2012). Its applicability in many research studies has affirmed the view of researchers who believe its findings are very reliable (Udousung & Umoh 2012).

Ethical Considerations

Since this paper did not rely on primary research, there were minimal ethical implications for the project. Nonetheless, the main ethical consideration of the research was the proper citation of secondary materials to avoid any instances of passing off the works other researchers as authentic work. To this extent of the analysis, this research explicitly states that most of the findings deduced in this paper relied on previous research conducted by other researchers.

Limitations of the Study

The main limitation of this study is its indicative nature, as opposed to its pragmatic nature. In other words, the research findings are only indicative of the causes of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria. There may therefore be slight deviations between the findings of this paper and the findings of more pragmatic researches.

Findings

Despite the categorisation of the data analysis techniques, the data analysis process showed that one econometric technique would have easily addressed the research topic (the unavailability of reliable research information hindered the application of multiple data analysis methods). Sometimes, when the research information was available, it was defective. Given this limitation, the research had to rely on less-suitable techniques, thereby introducing a new caution in the interpretation of the research findings (since the less suitable techniques would possibly introduce new defects in the findings). Nonetheless, the findings of the multiple regression analyses mentioned in chapter four of this dissertation show that the independent variables accounted for about 96% of the fluctuations of exchange rates in Nigeria. This finding emerged from a high explanation of the exchange rate through the co-efficient of multiple regression (R2) which stood out as R2 = 0.96 (the 0.96 variation explains why the independent variables explained about 96% of the total exchange rate variations). When the co-efficient of multiple regressions adjusted to accommodate these independent variables, it only slightly changed to 94%. This minimal deviation showed that the regression analysis provided an acceptable fit of analysis.

In this analysis, the Durbin Watson statistic was used to investigate the presence of serial correlation and it showed that there was no serial correlation in this regard (there was only a 1% significance level, thereby denoting an insignificant serial correlation). This finding emerged with a consideration of the fact that the Durbin Watson statistic method measured the presence of serial correlation, not just by evaluating the number of observations, or the number of independent variables, but also by considering the time-effect of the independent variables on the relationship under analysis. Through the understanding of the adoption of the Durbin Watson statistic, time emerged as an important variable in the research as well. Many researchers concur with this view, but they often express some sense of helplessness with the process of measuring this time (Udousung & Umoh 2012). For example, issues like changes in demand patterns and technological advancements occur as important time functions that may significantly affect the outcome of such findings. The inclusion of time patterns in this analysis therefore captures the technological changes and other time functions during the period of the research. The overall results of the multiple regressions occurring in this study manifested as b1, b2, b3, and b4. These estimates occur from the association of the independent variables (inflation, terms of trade, interest rates, and current capital account deficits) and the dependent variable (exchange rates). Inflation and interest rate data came from the central bank of Nigeria financial records. Data for capital account deficits and terms of trade were proxies. Auxiliary data incorporated in the paper however came from the information bulletin of the federal ministry of Statistics.

An analysis of the long-term dynamic models for evaluating the causes of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria show that the Nigerian exchange rate is highly responsive to domestic prices and the interest rates charged on foreign money. This finding emerges from an analysis of several empirical studies, which showed that the exchange rate responded to domestic prices negatively, while it showed a positive response to interest rates charged on foreign funds. However, the country’s capital accounts also affect the domestic price level, thereby drawing an inferred relationship between the country’s capital accounts as a determinant of real exchange rate.

Further tests to ascertain the causes of real exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria showed that in the long-term, money circulation, and domestic interest rates significantly affected the rate of exchange rate volatility in the market. More specifically, the rate of interest charged on domestic money emerged to be among the most influential factors that affected the level of money supply in the economy.

The level of government spending also emerged as a significant determinant of exchange rate volatility because it affected the national capital accounts and possibly, the money supply in the economy. A greater percentage of analyses made to ascertain the impact of government spending on real exchange rate show that government spending and exchange rates share an inverse relationship, in reference to trade and the level of output (mainly) (Bolaji 2012). Other ways that government spending impacts exchange rate volatility is through its depletion of foreign reserves. This finding resonates with similar findings by Bolaji (2012) which show, “the level of monetary balance in the monetary sector (M2=RMB) is predominantly determined by the level of capital account balance, real gross domestic product, domestic and external reserves” (p. 677).

An analysis of this finding, through the regression model, shows that the status of the country’s capital account has a significant impact on the domestic interest rates and the bank reserve rate. This influence is highly responsive to the nominal exchange rate (through the influence of trade). This paper also established that the openness to trade and the real output of the economy did not have any significant impact on the real exchange rate. However, since they had a significant impact on the country’s capital account, they indirectly affected the exchange rates by indirectly affecting the current account balances of the government.

Discussion

From the findings of this paper, the identification of inflation and interest rate as two of the greatest causes of real exchange rate volatilities affirm previous research which have identified the same factors as some of the greatest causes of exchange rate volatility in not only Nigeria, but other countries as well (Abdelaziz & Chortareas 2008; Al-molly & Norma 2012). The causes of exchange rate volatilities have a critical role to play in defining the economic health of Nigeria because they outline among the most important macroeconomic indicators of the economy. It is therefore unsurprising that the Nigerian government tried severally to stabilise the country’s exchange rates. This attempt by the Nigerian government is similar to other governments because Van Bergen (2010) says exchange rate is among the most watched economic measures of modern economies (especially in a globalised society where different countries trade with one another).

Through the credibility of the analysis conducted in this paper, interest rate and inflation emerged as the most notable causes of exchange rate volatilities in Nigeria. This paper also identified several reasons that affect these causes, in no specific order. For example, this paper shows that movements in oil prices may affect inflation rates and interest rates respectively. Notably, increases in oil prices affect the Nigerian economy negatively because it increases interest rates, thereby fuelling the possibility of realising a recession. Nonetheless, it is important to evaluate these factors in more detail

Inflation

Nigeria has reported inflation as a common macroeconomic problem, since the seventies (Enoma 2011). Nigeria however reported moderate inflation rates before the introduction of the IMF-sponsored SAP program (Enoma 2011). After the change of the exchange rate regime, the country has witnessed intolerable inflation levels. Most analysts trace Nigeria’s inflation problems to the discovery and the boom of the oil sector, which significantly increased the government’s public expenditure (Abdelaziz & Chortareas 2008; Al-mulali & Normee 2012). This situation led to a sporadic increase in the public demand for goods and services, while at the same time, the economy could not increase its supply to match this demand. This situation therefore created a huge momentum in the increase of the general price level of goods and services in the Nigerian economy. From this analysis, the Nigerian public spending plan largely depended on oil revenues. As history would have it, this over-reliance on the oil sector caused a lot of vulnerability of the Nigerian economy to the intrigues of the oil sector. Therefore, when global prices of oil collapsed, in the early eighties, the Nigerian government experienced significant budget deficits. The government’s monetary policy was also highly expansionary (in part, explaining why the country’s inflation stood at 40%). Stated differently, the slump in the oil sector led to a significant decline in imported goods, thereby increasing the inflationary pressure in the economy.

The introduction of the SAP in 1986 did not solve Nigeria’s exchange rate problem, as it caused a further decline in the value of the Naira, thereby affirming a relationship between the exchange rate and economy’s inflationary pressures (Omotor 2008). This relationship cements the application of the quantity theory of money, which stipulates the existence of a positive relationship between money supply and inflation. In detail, the theory suggests that a significant increase in the money supply would automatically lead to the same level of increase in the country’s inflation level. Nonetheless, a general rule in economics stipulates that if an economy realises low inflation rates, it is likely to report appreciated exchange rates (Abdelaziz & Chortareas 2008; Al-mulali & Normee 2012). If the inflation rates stabilise, the exchange rate is also likely to stabilise as well.

Most developing economies like Nigeria generally report high inflation rates, thereby fuelling the devaluation of their currencies. Comparatively, most developed economies, like Japan and Germany, report low inflation rates, thereby further stabilising their exchange rates. Some developed economies, like the US and Canada, have only recently started enjoying stable exchange rates because of their low inflation rates. This outcome asserts the findings of the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis, which stipulates that most countries with a high per capita income have low inflation rates (less volatile exchange rates) compared to countries which have a low per capita income (high inflation rates and volatile currencies). Therefore, an analysis of the Naira against the US dollar largely follows this trend because Nigeria is a country with a low per capita income, thereby experiencing a high inflation rate, compared to America (the Naira is compared to the US dollar), which reports a low inflation rate. The high inflation rate of the Naira therefore means that its currency will be mostly depreciated (compared to the dollar). This analogy largely shows how inflation emerges as a strong determinant of exchange rate fluctuations in Nigeria (through the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis).

Interest Rates

Based on the analysis of this paper, it is very difficult to isolate interest rates from the rate of inflation (as described above). Similarly, as Van Bergen (2010) argues, it is difficult to isolate interest rates and inflation from exchange rates. These three factors (interest rates, inflation, and exchange rates) therefore share a high correlation. This correlation manifests through the action of the central bank of Nigeria to influence the exchange rates by manipulating the interest rate and the bank reserve percentage. Certainly, by influencing exchange rates, the government aims to control exchange rates by controlling inflation as well. Low interest rates amount to high inflation in the economy and weaker foreign exchange rates. The opposite is also true because if the central bank (through commercial banks) introduce high interest rates in the economy, there is likely to be a low inflation level and an appreciated currency. In a broader sense, the existence of a high interest rate in the economy shows that most lenders will have a higher payoff for investing money in the economy. This situation is likely to increase investor appetite in the economy because most investors would demand more domestic currencies (for investments), thereby causing an appreciation of the currency. A high inflation rate in the economy would however mitigate this effect because a slight appreciation of the currency would be “swallowed” by the high inflation rate. Other factors may also lead to the same outcome, especially if other countries post low inflation rates.

Through the above analysis, interest rates emerge as the main tool for mobilising resources for economic growth and development. The fluctuation of these interest rates also emerges as an effective tool for the Nigerian government to use in ensuring the proper management of its economic resources. In sum, interest rate fluctuation is an important indicator for macroeconomic performance because on one hand, it affects the consumption of goods and services in the economy, and on the other hand, it defines the appetite for investment. In a more practical perspective, the interest rate largely dictates economic growth in the real sense of the concept. However, at this point, it is important to say that most investments are not necessarily exogenous because they are not exclusively reliant on the level of income alone (since interest rates and business expectations define the level of investments too). Relative to this assertion, Van Bergen (2010) says, “Investors can borrow money at one lending rate because there is a structure of interest rates, due to differences in risks, financial uncertainty, and transaction costs” (p. 5). Since interest rates affect different functions of an economy (including exchange rates), it is important to understand the factors that influence the interest rates, as they are equally bound to influence the level of the exchange rate (by association).

Current-Account Deficits

Current-Account deficit emerged as an important determinant of the exchange rate in Nigeria because it denotes the trade imbalances between Nigeria and other economies. Current-Account deficit mainly denotes the overall payments and receivables that the country makes for the goods and services that it trades with its partners. An unfavourable balance of payment would occur if Nigeria spends more money on imports than it receives through its exports. Stated differently, this situation would lead to current account deficits. Often, in such circumstances, the government would have to borrow money from different sources to counter its deficits. This situation manifests in Nigeria because foreign currency revenues that the government has received through its exports does not meet its foreign reserve requirements. The same situation outlines another unfavourable macroeconomic situation where the government oversupplies the Naira for its domestic products and services, thereby making it cheaper for foreign investors to purchase goods and services in the economy (leading to a devaluation of the Naira). The excessive demand for foreign currency also does not do much to improve this situation.

Egwaikhinde (1997) says that the capital account deficit realised by the Nigerian government largely traces to its expansionary monetary policies, which have seen money generation from the central bank finance the capital deficit. Unfortunately, this outcome has also increased the level of inflation in the West African economy. Another unfortunate situation that has emerged from this analysis is the fact that the expansionary monetary policy adopted by the central bank has largely shown no alignments with the exchange rate policy as outlined by the government.

Statistically, Nigeria’s current account deficit significantly deteriorated throughout most parts of the late seventies and early eighties. In fact, Adedeji (2001) says, since 1985 to the late 2000s, the Nigerian current account performance has always registered significant deficits. Through this analysis, Omotoye & Sharma (2006) say that there has been a significant relationship between Nigeria’s current account deficit and budgetary deficit, especially because budget deficits reflect current account shortfalls. This situation mainly arose from the failure of the country’s supply for goods and services to meet its demand.