Introduction to the Study

The amount of funding that libraries receive, affects the quality of services they can offer. In the United States of America, federal, state, and local i.e., municipal and government funding are the main sources of money for public libraries (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010; Research Information Network, 2010). However, to be precise, state and local government funding are the main sources of money for these institutions (American Library Association, 2014); federal funding only complements these sources of revenue (American Library Association, 2014; Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010). Legislatively, the Library Services and Technology Act lobbies for funds from Washington for these public institutions. Some public libraries receive extra financial support from concerned citizens, who may give private donations or support the activities of a special-purpose district by voting for and paying specifically levied taxes (American Library Association, 2014). Such efforts highlight a wider source of funding for public libraries (i.e., private philanthropy), which has often played an instrumental role in expanding public library facilities and renovating them (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010). These institutions have also taken recourse to such funding sources to improve their services. Another critical source of public funding is the endowment fund (Sullivan, 2007). Some innovative library administrators have gone a step further and sought additional funding through private-public partnerships with private companies and civic groups.

In the last few years, the United States government has been criticized for being tightfisted with respect to public libraries (American Library Association, 2014). This is part of a wider set of concerns regarding the funding of public libraries at the expense of other economic projects (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010). Based on these pressures, Lumos Research (2011) and Lemons and Thatchenkery (2012) noted that it is now common to see public libraries collaborating with profit-making organizations to supplement their income. This is why public-private partnerships are becoming a common feature of the funding model of public libraries (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2013). Overall, these factors show the immense pressures that public libraries are experiencing in today’s uncertain economic times.

Statement of the Problem

Since the 19th century, United States public libraries have played a crucial role in the social and economic development of communities (Rubin, 2010, p. 7). For instance, they have supported literacy of the homeless, acted as social gathering places, allowed for personal and professional development and acted as centers for cultural engagement (American Library Association, 2013a). As Obadare (2014) and the Research Information Network (2010) observed, these institutions came under threat from social and economic changes on two fronts: First, the growing prominence of the digital era diluted the relevance of libraries in today’s society by increasing access to information and eliminating the monopoly that most libraries used to enjoy in this regard (Basri, Yusof, & Zin, 2012; Düren, 2013). Second, libraries are under threat from poor economic conditions, which have limited state and federal funding to such institutions (Bowman, 2011; Coffman, 2013). The American Library Association (2013b) stated that, today, American libraries are experiencing the greatest threat to their financial stability in their history.

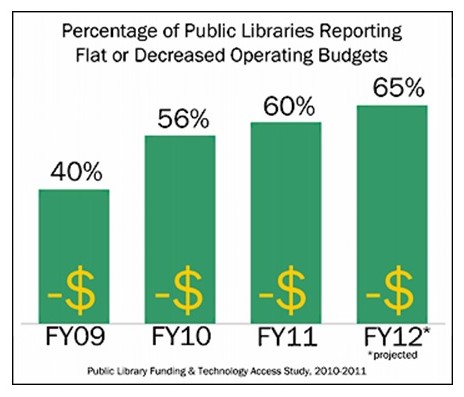

During the recent global recession of 2007/2008, public libraries in 44 states around the United States reported a 30% decline in state funding (Lumos Research, 2011). Europe reported a similar trend because reduced funding caused the closure of several public libraries in Western Europe (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2013). Furthermore, data gathered in the United Kingdom from senior library managers, in 2009, showed that most libraries were experiencing sustained periods of financial cuts (Research Information Network, 2010). Based on the scale of financial cuts experienced by most of these institutions, the network also showed that many library administrators were reviewing the scale of services offered to their patrons (Research Information Network, 2010). Indeed, to cope with the financial challenges, some public libraries stopped operating, others downsized their operations, and a few reduced their working hours (Bakar & Putri, 2013; Klentzin, 2010). Such adjustments have curtailed the effectiveness of these public institutions in fulfilling their social and educational goals, thereby reducing their relevance in modern society even more (Egunjobi & Awoyemi, 2012).

Policymakers have contributed to the decline of public libraries by reducing public funds that have traditionally financed such institutions (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010). Instead, legislators and county administrators believe that there are other important institutions, such as schools, security agencies, and health care facilities, that need public financing besides libraries (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010). Consequently, many of these institutions have shut down their operations, imposed levies for accessing their services, or ventured into other types of business (Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010). For example, the oldest public library, Darby Free Library, located in Delaware County, is facing closure because of severe budget cuts (Chang, 2014). Similarly, the Friern Barnet Community Library, in London, closed down after Barnet County was unable to finance its operations (Webb, 2014).

Based on the unprecedented scale of financial challenges that constrain the operations of modern libraries, different researchers and organizations have undertaken comprehensive research studies to assess the scope of the problem (Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011; Goodman, 2008; Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2010; Webb, 2014). For example, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (2010) and the Research Information Network (2010) have gathered information regarding the scale and scope of financial troubles that plague the American library sector. Other institutions that have participated in similar research studies include the Society of College, National, and University Libraries (DeAlmeida, 1997; Goodman, 2008). Goodman (2008) added that some small focus groups produced vital information regarding the scope and magnitude of the financial troubles that characterized the library sector. In line with the same goal, many library directors acknowledged the financial problems they experienced when managing the operations of public libraries (American Library Association, 2014; Mapulanga, 2013). Consequently, they have introduced new services to support their organizational goals. However, limited financial resources constrained their strategies. Furthermore, public libraries operate as legal non-profit institutions. Adopting a financial diversification strategy means that these institutions would make profits. This approach contradicts the operational model of such institutions because they are not supposed to make profits (Bakar & Putri, 2013; Klentzin, 2010). This challenge highlights the need to understand the legal ramifications of adopting a financial diversification strategy. The operational dynamics of public libraries, which have steered it on the path of non-profit business, would also conflict with a financial diversification strategy because they would not support profit-making ventures (Bakar & Putri, 2013; Klentzin, 2010). This challenge forms the second basis of analysis for this study.

Financial diversification is a strategy advanced by many economic experts to manage economic challenges. While many research studies have been devoted to this topic in the context of private enterprises (Agosto, 2008; Brands & Elam, 2013), the scholarly literature is silent on financial diversification in the public library sector. The few authors who have addressed the financial straits in the public sector suggested that public libraries should be seeking alternative sources of funding (Goodman, 2008). For example, Mapulanga (2013) advocated that Malawian public libraries should try to find extra money through fundraising efforts. In addition, the author encouraged these institutions to focus on and start income-generating activities to supplement their income. In the American context, some researchers have suggested different strategies of financial diversification. Cuillier and Stoffle (2011), for example, suggested, in their study on Arizona libraries, that these institutions should consider charging library fees and creating award ceremonies as alternative sources of funding.

Many researchers have explored how financial diversification could work in various enterprises; however, they mostly considered profit-making enterprises (Bakar & Putri, 2013; Brands & Elam, 2013; Klentzin, 2010). Some common recommendations emerged from such studies; one of them was, for example, to encourage companies to venture into new businesses – engage in horizontal and vertical diversification (Agosto, 2008; Brands & Elam, 2013). Many privately owned companies have embraced such recommendations successfully (Bakar & Putri, 2013; Brands & Elam, 2013; Klentzin, 2010). These strategies have, indeed, helped them to overcome some financial challenges and cope with uncertain economic conditions. While success stories abound about private enterprises who took some hurdles and overcame their financial limitations, information regarding what public institutions might do, likewise, is wholly inadequate (Agosto, 2008).

Based on the current literature, it appears that researchers have, indeed, suggested various alternatives for improving the financial positions of libraries in their vicinity. However, their suggestions are broad (Brands & Elam, 2013; Kostagiolas, Papadaki, Kanlis, & Papavlasopoulos, 2013). Based on this background, few of them have explored the implications of these strategies on the current operational structure of public libraries, which limits their mandate to providing free social services. What did emerge, however, from these writings was the growing awareness that dependence on state and federal funding to finance the libraries’ operations was not sustainable (Brands & Elam, 2013; Kostagiolas et al., 2013). It appears that various institutions will have to seek different sources of funding to suit their particular circumstances and financial needs. This dawning understanding informs my choice of the case study design, which takes into account the contextual nature of the problem and, thus, of the search for financial options available to Clayton County Library System, Georgia.

It is unknown how financial diversification could improve the economic fortunes of public libraries. According to Basri, Yusof, and Zin, (2012), researchers who did focus on the financial troubles affecting public libraries have explored only how to improve library efficiency, but not its financial sustainability. Others have explained the reasons for budget deficits in the library sector (Bedford & Gracy, 2012). Because private organizations have different operational needs and requirements, one cannot apply these findings indiscriminately both to public and private enterprises. Insufficient information exists about public libraries and how they could improve their financial lot through diversification. In this regard, there is a need for public libraries, such as Clayton County Library System, to explore alternative financial investment strategies that could improve the situation.

Purpose of Study

Based on the many financial challenges that modern libraries are currently experiencing, the Research Information Network (2010) observed that library directors are willing to use this economic challenge to do things differently. However, few of them have come up with concrete proposals that would effectively transform library management services so as to produce large-scale savings and improve the financial position of these organizations (Cummings & Worley, 2009). These failures have made library administrators eager to look for innovative ways of solving the financial problems that are plaguing their organizations (Wang, Chu, & Chen, 2013). However, there is only scant information regarding how nonprofit organizations might achieve financial sustainability without adopting financial diversification strategies that have been predominantly associated with the corporate sector (Humphery-Jenner, 2013).

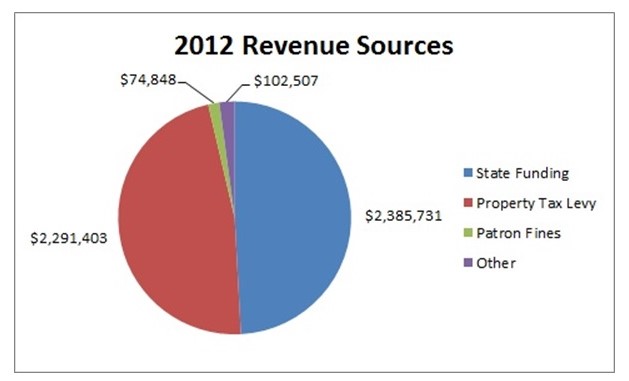

The purpose of this study is to provide a thorough understanding of the unique structural, legal, and operational dynamics associated with adopting a financial diversification strategy in Clayton County Library System and explore what would support or, conversely, hinder this strategy. Based on this line of reasoning, this study strives to paint a clear picture of the unique administrative, legal, and operational dynamics associated with public libraries by investigating the financial problems of one public library in Georgia – Clayton County Library System (CCLS). Indeed, CCLS is among many other public libraries in 44 states of the United States that are suffering from financial challenges. This view aligns with the assertions of Collins (2012), who maintained that 44 of the 50 states of the union have state-funded public libraries that continually experience financial challenges. The Clayton County Library System (2014), Georgia, serves more than 1 million users annually. The organization also supports local businesses, which, in turn, support the library by providing business information such as directories and databases, literacy programs, and similar supportive goods and services. Some of the organization’s financial troubles stem from a wider problem facing public libraries in the United States, namely, relying on public funds to sustain their operations (American Library Association, 2014). This observation supports the assertions of Coffman (2013) who wrote that approximately 90% of all public library funds come from the government. Library fees and direct taxes account for other sources of revenue for such institutions (American Library Association, 2014). Relying almost exclusively on public funds to run their operations, public libraries such as the Clayton County Library System are vulnerable to economic uncertainties.

Financial constraints and the digitization of information, which formerly was nearly the exclusive domain of libraries, have reduced the bargaining power of the Clayton County Library System as it seeks more financial allocations from state and federal authorities (Egunjobi & Awoyemi, 2012). Furthermore, with a diminished relevance in today’s society, the institution is receiving less public support, compared to years past (Bedford & Gracy, 2012; Cooperrider & Whitney, 2009). Collectively, these challenges threaten the organization’s existence. It is to these severe challenges that this study will address financial diversification concerns with the hope of finding answers to enhance the financial sustainability of the Clayton County Library System. In doing so, ways and strategies will be sought that can benefit other public libraries in Georgia (and the greater United States) that share a common predicament in these uncertain economic times. Comprehensively, Clayton County Library System is a prime example of a non-corporate entity that needs these financial diversification strategies. Furthermore, today’s digital growth has created more pressure on public libraries to maintain their relevance in a fast-paced world (Basri et al., 2012). What this means for Clayton County Library System is that it needs to find answers to its financial problems, or it could face closure, and what Clayton County Library System experiences seem to be felt across the library sector in general. Because there are no models or frameworks that could predict how a financial diversification strategy might promote the financial stability of these important social institutions (Kostagiolas et al., 2013; Christoffersen & Langlois, 2013), it is both crucial and timely that a qualitative case study be focused on Clayton County Library System.

Research Questions

Main Research Question

How can Clayton County Library System diversify its funding sources to become financially sustainable?

Subquestions

- What are the structural implications of adopting a financial diversification strategy at CCLS?

- What are the legal considerations for the adoption of a financial diversification strategy at Clayton County Library System?

- What are the operational implications of adopting a financial diversification strategy at CCLS?

Theoretical Framework

The modern portfolio theory is the main theoretical framework for this study. This theory seeks innovative ways for maximizing returns within a given variety of investments owned by an individual or an organization (Cross, 2011; Okojie, 2010). The main preposition of the modern portfolio theory is risk minimization through portfolio diversification. This theory has shaped how investors perceive risk and returns. Okojie (2010) also says it has affected how investors understand portfolio management. In the same way, it seeks creative ways of minimizing risks by evaluating current assets. Early adopters of the theory emerged in the early 1950s and again in the 1970s (Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). They mainly presented the theory as a mathematical model of finance. The theory is based on the work of Harry Markowitz, who developed the model to help investors make prudent decisions regarding their investments (Tu & Zhou, 2010). Soon after its development, people termed the theory the Markowitz theory (Omisore, Yusuf, & Christopher, 2012). However, its name was later changed to the modern portfolio theory. Omisore, Yusuf, and Christopher (2012) considered it among the first theories that helped investors to maximize their portfolio returns by allowing them to choose the proportions of different investment assets. Unger (2014) explained that the modern portfolio theory divides financial risks into two parts. The first part is the unsystematic asset-specific risk, which investors could mitigate through diversification (Tu & Zhou, 2010). The second part is the covariance, or market risk, which always remains with the investor. These risks underscore the importance of investing through portfolios, as opposed to holding on to individual assets, or sources of funds (Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). When developing the modern portfolio theory, Unger (2014) outlined four assumptions. First, he maintained, most investors are preoccupied with the mean and standard deviation of their assets, when making investment decisions. He further assumed that most investors are risk averse as they prefer to make investment decisions that present fewer risks, for equal returns.

Chapter 2, will elaborate in greater detail on the theoretical propositions and major hypotheses of the modern portfolio theory, but suffice it to say for now that many pundits have questioned some of its major assumptions (Omisore et al., 2012). Although these criticisms must be taken into account, Han, Yang, and Zhou (2013) argued that the theory presents an improvement over the traditional models of wealth development. Furthermore, it marked an important advancement in the mathematical modeling of investment decisions. This fact stems from the theory’s mathematical formula for making investment choices (Han et al., 2013). The purpose of developing this formula was to highlight the fact that investment portfolios have fewer risks associated with them than an individual asset would carry. It is possible to see the intuitive value of this contribution because different assets have varying values (Han et al., 2013). Thus, the modern portfolio theory advocates for diversification to lower the risk of investment, regardless of the nature of correlation that most assets share with returns (Omisore et al., 2012).

Researchers have used the modern portfolio theory to encourage investors to pursue asset diversification as a strategy for insulating their investments against market risks and organization-specific risks. In this regard, Omisore et al. (2012) wrote, “The theory is a sophisticated investment decision approach that aids an investor to classify, estimate, and control both the kind and the amount of expected risk and return” (p. 21). Based on these dynamics, an essential component of the modern portfolio theory is the central relationship between risk and return (Elton, Gruber,& Blake, 2011). The assumption that all investors need to receive risk compensation also emerges as a critical tenet of the theoretical framework. The modern portfolio theory shifted the emphasis of investment strategies from focusing on the characteristics of specific investments to focusing on the statistical relationships that underscores every investment decision (Edlinger, Merli,& Parent, 2013). Here, researchers used the modern portfolio theory as a framework for guiding investors on how to allocate capital across an asset group (Edlinger et al., 2013). Investors measure investments based on their expected value of the random portfolio return (Elton et al., 2011). The risk quantification process also occurs by analyzing the variance of the portfolio return, mean variance framework. The portfolio allocation process should consider the conflicting goals of investments and the quest for investors to minimize their risks and maximize their returns (Bhattacharya & Galpin, 2011).

Overall, Markowitz was among the first scholars to observe the diversification effect by encouraging investors to diversify their financial options across different assets. At this point, Bhattacharya and Galpin (2011) explained that, when applying the modern portfolio theory, it is important to understand the returns, variances, and correlations that characterize the mean variance approach that investors use to choose the right portfolios for their investments. Again, this process helps investors to maximize their returns, while minimizing their risks when making investment decisions (Bhattacharya & Galpin, 2011). Since the modern portfolio theory hails from a financial background, it provided the framework for comprehending the financial alternatives of Clayton County Library System.

Nature of the Study

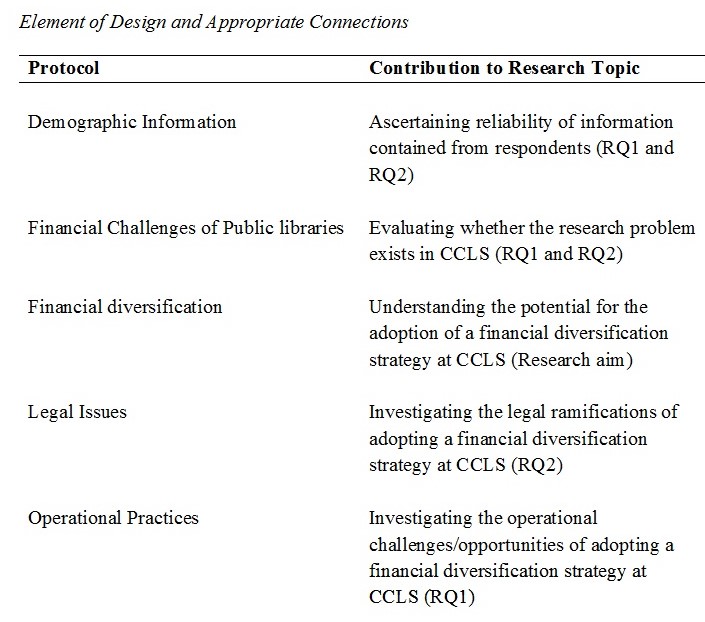

This research study uses a qualitative approach to address the research questions. This approach allows for the exploration of the research phenomenon in-depth (Thatchenkery, 2005; Maxwell, 2013). The qualitative research approach was appropriate for the study because of its exploratory nature. Since library managers rarely use financial diversification in public library financial management, we did not know what to expect. The qualitative research design is mostly applicable in such situations (when we do not know what to expect from a study). The research design also helped to delve deeper into the nuances of the research questions (legal, operational, and structural issues that relate to the adoption of a financial diversification strategy). The research questions accommodate these nuances and therefore, align with the qualitative research approach. Furthermore, it accommodates the case study design, which gives room to explore the financial practices of Clayton County Library System through dual data collection techniques – interviews, and document reviews. Marketing researchers have mainly used the qualitative research approach because of its open-ended nature (Qualitative Research Consultants Association, 2015). For example, they have used it to develop hypotheses for further testing, understand people’s feelings, values and perceptions, generate new project ideas, and undertake similar actions in marketing development (Qualitative Research Consultants Association, 2015). These competencies of the qualitative research design show the inappropriateness of the quantitative research approach because it has a conclusive nature. Stated differently, the quantitative research approach could not accommodate the exploratory nature of this study because the information used in this paper lays the groundwork for further research into the field of financial diversification in the public library sector.

The data collection process includes in-depth interviews of 20 respondents. Seven respondents would be current and former members of CCLS’s top management team. They will be existing and former library directors of CCLS. Three members would be grant writers, while six branch managers and four assistant directors will take part in the study. The second part of the data collection process would be the document review stage, which will garner information from books, journals and credible websites. The purpose of this data collection method is to fill knowledge gaps that would emerge from analyzing primary data obtained from the interviews. This way, there would be a coherent research design for answering the research questions. Once the data is collected, content analysis method will be used as the main data analysis technique for the document review process. This method will allow categorization of the data into relevant themes for answering the research questions (Weick, 1982). Likewise, it will help in categorizing and summarizing the results for the document review. In essence, themes from the interviews will be used to organize materials gleaned in the document reviews. This method will be applicable at two levels: The first level will provide a descriptive account of the information obtained; the second level, or the latent level of analysis, will interpret the findings gained from implied meanings in the responses, and from the inferences made.

Definition of Terms

Following are the definitions of terms as used in this study:

- Digital age: The digital age is the current era, characterized by the transition from an industrialized to a computer-reliant global economy. Technically, this period started in the 1970swith the introduction of personal computers. Technological advancements have helped to redefine this period by making it easy for computer users to transfer information. Besides the heavy reliance on personal computers, the increased use of the Internet as a global platform for information and knowledge sharing also characterizes the digital age. Other names used to capture the concept of the digital age are synonyms such as computer age, information age, and new media age (Pavlik, 2013).

- Financial diversification: Financial diversification is an economic strategy used to manage risks. Financial experts have used diversification to manage risk portfolios by reducing the risk of one security by spreading it across different investments (International Monetary Fund, 2013). Experts may do so by investing in different types of assets or by mixing different types of investments (International Monetary Fund, 2013). In the context of this study, financial diversification refers to the process of seeking new ways of generating revenue to supplement the operational expenses of a public library. This strategy could help such organizations to terminate or, at least, reduce their reliance on public funding.

- Financial mitigation: Financial mitigation is a process whereby the severity of an adverse effect is lessened (International Monetary Fund, 2013). In this study, the term is used to describe the reduction of financial exposure of public libraries.

- Financial sustainability: Financial sustainability is the economic state of a country, person, company, or institution that is resistant to economic instabilities; thus, financially sustainable entities are able to fulfill their basic functions easily (International Monetary Fund, 2013). This study uses the concept of sustainability to denote a state in which the Clayton County Library is immune to economic shocks that cause an unstable financial cash flow. Therefore, by adopting a financial diversification strategy, this researcher predicts, that the organization’s financial intermediation process would have a smooth functionality. This way, people could have renewed confidence in how the public library system manages its operations.

- Generalizability: Generalizability means that the findings of a study can be applied to a wider population beyond the sample studied. Here, it means that the views detailed in the study may also reflect the views of a wider population that shares similar characteristics with the sample(Patton, 2002). In the context of this study, the term also refers to the ability to generalize the financial strategies of the Clayton County Library System to other public libraries that share similar characteristics.

- Public-Private partnership: Public-Private partnership refers to collaborative efforts between government enterprises and private enterprises to complete a project (International Monetary Fund, 2013). In this study, the concept refers to a potential relationship that would emerge if public entities (i.e., public libraries) collaborated with other stakeholders in the library sector to promote financial stability in the sector.

- Replication logic: Replication logic in qualitative research means that two or more cases support the same theory either by predicting similar results or producing contradictory results, but for predictable reasons. This process improves the generalizability of the findings obtained (Maxwell, 2013).

Assumptions and Limitations

This section will present the assumptions and limitations in the study.

Limitations

This study will focus on Clayton County, Georgia, with a special emphasis on understanding how Clayton County Library System could improve its financial sustainability by adopting a financial diversification strategy. Within this scope of analysis, the study will promote a deeper understanding of public policies and administrative practices that underscore the financial problems of the library system and, by extension, of public libraries that share similar characteristics. Thus, participation will be limited to individuals who understand the financial practices of public libraries and are presently working or have worked in CCLS. Furthermore, a special bias exists for collecting the views of professionals who occupy positions within the administrative structure of CCLS because they are familiar with the financial practices of the library system.

One limitation of the study may be the limited number of respondents that will be available for interviews, considering their busy schedules. When developing the interview protocol, the busy schedules of top library administrators and their potential unavailability during the time span scheduled for data collection will be considered. Furthermore, based on the time frame of this study, the possibility that some of the library personnel i.e., the potential respondents may have retired, move to other positions in other library systems, or leave the service for other reasons will be put into consideration. Despite these limitations, strong efforts will be made to reach an adequate number of uniquely qualified respondents.

Methodological limitations of this study will also be considered. For example, the case study design could limit generalizability (Maxwell, 2013). Similarly, because a case study often involves only one researcher, as does a study conducted for the purpose of gaining an academic degree, the possibility of researcher bias will be considered. Other methodological weaknesses of the study could arise during content analysis, a method that will be outlined in the Data Analysis section of Chapter 3. The availability of research materials could affect its credibility. In this regard, observed trends may not necessarily reflect the true picture regarding the adoption of a financial diversification strategy at Clayton County Library System.

To address these limitations, the findings of this study will be subjected to an independent review committee. The committee will identify areas of commission or omission that may require correction. Similarly, should the availability or unavailability of research data limit the application of the content analysis method, efforts will be made to ensure that sufficient objective materials are available when applying the theoretical framework.

Threats to quality could also be considered as limitations of the study. Such threats could affect the theoretical validity, construct validity, or internal validity of the research. Patton (2002) noted that threats to theoretical validity may arise from unnecessary duplication of research information and theoretical isolation. He added that threats to construct validity emerges mainly from respondents’ providing nonfactual information to either challenge or please the interviewer. To guard against such problems, established theories and concepts developed from earlier findings to support the research outcomes and answer to the research questions posed in the study will be used. Efforts to relate, but not duplicate, earlier findings to those of the current study will be made. In addition, to ensure validity and guard against bias, biased responses will not be included in the final report.

Assumptions

First, the study will assume that library administrators understand the financial situations of their library. In this regard, it will also be assumed that the administrators desire to change this situation by making libraries more financially sustainable. This assumption implies that the library administrators are desirous of understanding the nature of the financial woes besetting public libraries and of course, possible strategies that might mitigate existing conditions.

The second assumption in this study is that respondents will be knowledgeable about the financial practices of public libraries because they are holding administrative positions in the hierarchical structure of the organizations. The research design will address this concern and outline a framework for ensuring that the findings are valid.

Last, an assumption will be made that the qualitative research design would the best methodological approach for understanding the operations of public libraries and the possibility of realizing financial sustainability by adopting a financial diversification strategy. In this sense, it will be assumed that a qualitative research design could gather the most useful views and profit from the experience of key interviewees. While the methods section will indicate that the results of the study will be rendered as descriptive findings, nevertheless it will be assumed that the inclusion of expert opinions with the qualitative approach of the case study would provide a more focused understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Scope and Delimitations

Scope

The scope of the study pertains to the Clayton County Library System, Georgia. The feasibility of adopting a financial diversification strategy in a public library will be instigated first, by gaining a thorough understanding of the financial practices of this case in point and, then, by examining the possibility of improving its financial standing through the adoption of an economic diversification strategy. Clayton County Library System has approximately 30 supervisory staff and caters to the needs of everyone in the community (Clayton County Library System, 2014). Based on this dynamic, the study may lack randomness, but the research design will, nevertheless, allow for the generalizability of the results to other public libraries that share similar characteristics. It will do so by investigating the financial practices of other public libraries, or cases, as explained earlier with the concept of replication logic.

Delimitations

Strong (2014) defined delimitations of a study as unforeseen factors that characterize a research process. Delimitations could also be self-imposed conditions on the study that limit it (Strong, 2014). This study will have only two delimitations. The first delimitation will be imposed by the limited access to some respondents. The research design is aimed at garnering the views of library administrators who have very busy schedules. The limited time available for conducting this study may also affect the quality of information obtained from key informants. Library policies regarding employee conduct may impose other delimitations, as the responses given by employees of the library are subject to the limitations set by the organizational code of conduct. Thus, some employees may not be able to give responses that would be highly germane to the study and contravene their policy frameworks. Given the fact that the information regarding the financial practices of CCLS will be sought, some employees may feel that discussing their financial practices could cause security issues for their organization. To mitigate this concern, the researcher will seek managerial consent before interviewing employees. This way, the employees will be aware that management approves their participation in the study. Furthermore, the employees will be informed that the information obtained would mainly be for academic purposes. Their confidentiality in the process will also be guaranteed. A choice to broaden the analysis beyond CCLS is not considered because the research design only focuses on CCLS.

Significance of the Study

Academic Contributions

Public libraries provide important support services to social and economic institutions. However, poor economic conditions and increased public access to knowledge and information through the Internet have threatened their relevance and even their continued existence (Mapulanga, 2012). This study will add information to the debate surrounding the adoption of a financial diversification strategy in public libraries, by exploring alternative strategies that such institutions might adopt to achieve financial stability. This goal aligns with past reports that showed people’s appreciation for the value of public libraries in the social and economic development of many communities (American Library Association, 2014; Mapulanga, 2013). For instance, the American Library Association (2014) quoted a recent public agenda survey that showed more than 80% of the population stating that public libraries should still provide free public services to the community. It further stated that such a requirement should be a top priority of such institutions. This survey showed that most people believed that the services offered by public libraries were more important than other services offered, for example by the police or public parks (American Library Association, 2014). These statistics reveal that many individuals supported increased funding of public libraries. This outcome further reinforced the findings of the Pew Research Center (cited in Glen, 2013), which showed that more than 91% of Americans, 16 years and older, believed that the closure of public libraries affected the communities where the patrons hailed from. In fact, 63% of these respondents believed that such closures would have a “major” impact on communities (Glen, 2013). The proposed study would advance scientific knowledge regarding how public libraries would sustain their usefulness by showing how they could improve their financial positions through financial diversification. To do that, this study will highlight the structural, operational, and legal issues to consider when adopting the financial diversification strategy. By sorting out these issues, public libraries would be in a better place to continue providing their social services. Furthermore, future researchers would know what to consider when recommending new financial strategies for improving the financial stability of public libraries.

Policy Contributions

Exploring strategies for improving the financial sustainability of public libraries could promote policy development by changing management cultures (Albertini, 2013). Such changes would redefine the administrative policies of public institutions and improve public-private partnerships in the community (Mapulanga, 2012). The latter development could come from recommendations that explore different strategies for promoting the financial sustainability of public organizations through private-public partnerships (Reid, 2010).

Because this case study focuses on evaluating the possibility of adopting a financial diversification strategy of one institution, Clayton County Library System in Georgia, its findings and subsequent recommendations may introduce policy changes in the region by promoting financial literacy and proper financial management. Such developments may increase financial prudence in public and private spheres (Coffman, 2013). Furthermore, they may create increased awareness about financial challenges experienced by public libraries in the region. This measure would encourage policy makers to create local solutions for managing such problems (Bailey, 2011). Providing a proper legislative framework for financial innovation would be one way of doing so. Experts may further apply possible strategies that may emerge from such developments in the wider Georgia state.

Implications for Positive Social Change

The findings of this study would contribute immensely to the lack of adequate knowledge regarding the adoption of a financial diversification strategy in public libraries. By promoting financial sustainability at Clayton County Library System, this study will also contribute to the educational and cultural development of Clayton County because the public library plays an important role in providing educational and cultural resources to the residents (Massis, 2011). Therefore, if Clayton County Library System could meet its financial obligations, it could improve its services to the community and offer more educational resources to the residents. For example, it could increase its working hours and improve access to library services by adding new materials to its collections (Cottrell, 2011, 2012). Furthermore, by improving its financial situation, the library could employ more residents of Clayton County and support several families with the salaries earned at the organization (Ghosh, 2011).

Last, Clayton County Library System would support many local businesses that complement its operations. For instance, local publishers may supply reading materials to the library. Similarly, other vendors who supply educational materials to the library system may support the organization’s activities in different ways. In this way, a number of people who run businesses in Clayton County could depend on the library for earning a living. Indeed, due to these uncertain economic times and reduced public funding, such businesses also run the risk of closure (McMullen, 2011). Thus, Clayton County Library System could play a greater supportive role by promoting community development within its reach. Improving its financial position, would allow Clayton County Library System to reciprocally assist in improving local businesses. As a committee of library and information community members will review the findings of the study, in addition to further subjecting them to an independent review by the university’s doctoral research supervisors, the findings will have high reliability and validity. The results of the study could, therefore, be useful to library administrators and policymakers who influence funding decisions of such organizations and prove beneficial for the community of Clayton County, Georgia, and beyond.

Summary

The purpose of this research study is to provide a thorough understanding of the unique structural, legal, and operational dynamics associated with adopting a financial diversification strategy in Clayton County Library System and explore what would support or, conversely, hinder this strategy. The research questions align with this purpose because they explore the structural implications of adopting a financial diversification strategy at CCLS, investigate the legal considerations for the adoption of a financial diversification strategy at Clayton County Library System and find out the operational implications of adopting a financial diversification strategy at CCLS. These research questions would provide the missing knowledge of financial diversification in the public library sector. Evidence would come from a qualitative assessment of the views of library staff and past research studies that have investigated the same issue. These processes align with the modern portfolio theory, which is the main theoretical framework because it explains how organizations could achieve financial stability through financial diversification. Using this framework, the findings of this study would promote positive social change by improving the financial stability of libraries and helping them to continue providing their social responsibilities of information access. Similarly, they would expound the boundaries of the theory by explaining the legal, operational, and structural issues surrounding financial diversification in the public library sector. The next chapter is a literature review of past studies that have investigated the research phenomenon. It will review pertinent literature to broaden the understanding of the current financial status of public libraries and the difficulties they are facing in these uncertain economic times. A description of the literature search strategy and key search words used will be examined. In addition, the chapter presents the theoretical foundations of alternative funding through financial diversification strategies. Chapter 3 will present the research methods, including the case study approach and the rationale for selecting this method. In addition, the chapter explains complementing the case study by adding a sample of knowledgeable interviewees holding administrative positions in the hierarchy of library administration as well as some experienced grant writers from the library sector. The results of the study will be presented in a future chapter. Conclusions will be drawn based on the findings, and recommendations will be offered for practical application and future research on the topic.

Literature Review

Introduction

Financial diversification is a strategy used by many organizations to improve their financial positions. However, few studies explain how this strategy could work in the public library sector (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Coad & Guenther, 2014; Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). Based on this background, scholarly literature on financial diversification and its potential application in the public-library sector will be reviewed. This chapter will document three main issues:(a) the background of U.S. public library funding, (b) current financial challenges for U.S. public libraries, and (c) alternative strategies for public library funding. This information would help to fill the research gap concerning lack of sufficient information about the application of a financial diversification strategy in public libraries, especially in CCLS. The information contained in this chapter would help to meet the research purpose, which is to explore how CCLS can diversify its funding sources to become financially sustainable. The theoretical framework of the modern portfolio theory will undergird the exploration of how to bring financial diversification strategies to the public library sector. The chapter begins with an explanation of the literature search strategy, followed by a presentation of the theoretical basis for the analysis and the inherent definitions and organizational structures of public libraries in America. These analytical areas provide the context for evaluating the three aforementioned areas of the topic under study.

Literature Search Strategy

Literature search strategy was used to retrieve information mainly from peer-reviewed journals that have investigated financing issues in the American library sector. Supplementary research materials came from institutional websites and classic scholarly papers that investigated the same issue. Key words used in the search included: library funding, Clayton County Library System, library closures, modern portfolio theory, library trends, alternative strategies for funding, and public library management. I conducted the search with different search engines including Political Science Complete, Business Source Complete, SAGE Premier, Google Scholar, Emerald Insight database, Google books, and other Walden University research databases. For the initial research, key words were typed and words such as public libraries in America were added. This search strategy produced over 187 articles. To find the most relevant articles, research papers that were more than five years old and those that were not peer-reviewed were excluded. This process left over 114 articles that appear in the reference section of this document. When faced with challenges regarding the unavailability of research information, findings from other parts of the world were used and compared to those of the United States. However, deliberate efforts were made to use developed countries that have similar social, political, and economic characteristics as the Unites States of America.

Theoretical Foundation

The theoretical foundation of this study will be based chiefly on the modern portfolio theory. The theory emerged from the concept of diversification and from the need to improve financial stability. Corporate diversification is a common strategy in the corporate, or for-profit, sector. Essentially, the concept hailed from the common adage: “Never put all your eggs in one basket” (Cross, 2011, p. 140). This theory emerged from the seminal works of Harry Markowitz titled, “Portfolio Selection.” Albeit introduced more than 60 years ago, this work has evolved through the works of other researchers such as James Tobin and Bill Sharpe, who have won Nobel prizes because of their contribution to the understanding of portfolio diversification (Francis & Kim, 2013). Today, such works have influenced different people in different sectors, including portfolio management, individual investment decision-making and economics (Francis & Kim, 2013). Metaphorically, proponents of the theory hold that betting on one stock as the only financial strategy amounts to lack of diversification (Okojie, 2010). Diversification involves betting on different stocks. In the context of this study, investing in one stock would amount to depending on one funding source to finance library operations. Therefore, changing this status, or diversifying, means seeking alternative sources of funding. Alqudsi-Ghabra and Al-Muomen (2012) noted that one common benefit of doing so is to reduce the risk associated with relying on a single source of funding. The same principle that applies to the financial markets also applies here. For example, Cuillier and Stoffle (2011) wrote that it is common for one stock to lose its value by more than 50%; however, it is uncommon for a portfolio that has different stocks to lose its value by a similar margin. The modern portfolio theory, or the theoretical framework of this study, builds its concepts on this premise as it strives to maximize returns and reduce portfolio risk.

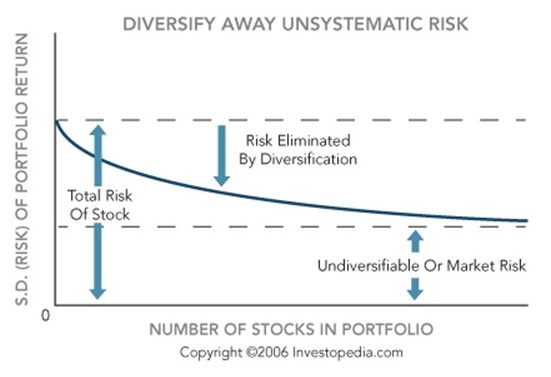

One important contribution of the modern portfolio theory in the financial field is its exhortation to investors to think about and compare the riskiness of a portfolio to that of a single security (Quantitative Solutions, 2012). Its contributions have mainly applied to the financial markets by encouraging investors to invest in different stocks, as opposed to one stock. Based on this analysis, the modern portfolio theory highlights two types of risk: systematic risk and unsystematic risk (Quantitative Solutions, 2012). Systematic risks are not industry-specific. Furthermore, avoiding systematic risks is difficult to achieve; therefore, they are also called unavoidable risks (Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). For example, the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center was a systematic risk. Unsystematic risks are industry-specific and are, therefore, diversifiable (Quantitative Solutions, 2012). The modern portfolio theory bases its principles on the unsystematic risk category because managers can diversify risks in this category. Figure 1 shows how the modern portfolio theory encourages the diversification of unsystematic risks.

When using the stock market analogy, it is crucial to point out that the more stocks one person holds, the lower the investment risk (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012). For an investor or an institution looking to invest, it is important to point out that one should select a broad-based portfolio. In applying this principle in the current study, it means that the modern portfolio theory encourages library administrators to seek a broad funding portfolio. Comprehensively applied, the modern portfolio theory strives to minimize risk within a given portfolio. In the context of this study, minimizing risks means seeking alternative funding sources for the Clayton County Library System and refraining from depending on state and municipal funding as the sole funding source. Financial analysts perceive diversification mainly in two ways: horizontal diversification and vertical diversification (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). Horizontal diversification entails increasing the portfolio with the same type of investments; vertical diversification involves increasing the portfolio with different types of investments (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012). In this chapter, both types of diversification will be reviewed in the literature.

The Link between Modern Portfolio Theory and the Diversification Concept

Revenue diversification is a relatively recent practice outside the financial sector (Deborah & Jones, 2009). According to the portfolio theory, revenue diversification has far-reaching implications for a not-for-profit firm because it will affect its revenue stability (Deborah & Jones, 2009). This effect has been a critical policy concern in not-for-profit firms and institutions (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012). One reason for adopting diversification is the benefits associated with it. Diversification is an old concept in corporate and institutional research (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Paliwal, 2013). Product diversification, geographic diversification, and portfolio diversification are the main concept divisions reflected in the literature (Deborah & Jones, 2009). Revenue diversification in particular bases its ideas on the modern portfolio theory. Here, the modern portfolio theory shows that different types of revenue sources have different variations. Diversification often reduces this variability. To explain this concept in detail, Kang (2013) explained that diversification encourages increased investment among different firms, thereby reducing revenue and profit volatility. In the same breadth of analysis, Paliwal (2013) stated that most firms could lower their financial risks by mixing different security holdings. Doing so, often reduces the financial risk of one security and allows the overall growth of the broad portfolio over time. The same explanation applies to the revenue structure of nonprofit organizations. Stated differently, a balance of different revenue sources could increase the financial stability of the institution, thereby reducing its overall financial risk in the long-term (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Deborah & Jones, 2009). Developing multiple and imperfectly coordinated sources of revenue is the best way of realizing the described advantages (Paliwal, 2013). Here, it is important to point out that the diversification theory strives to eliminate unique and unsystematic risks.

Nonetheless, even diversified portfolios are to some extent subject to market risks that affect other businesses as well (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Deborah & Jones, 2009). This fact closely aligns with the views of proponents of the dependency theory. Based on this theory, its advocates maintain that there is no need for diversification when resources are abundant because external dependency is not a problem (Tkachenko, 2012). However, during times of limited resources, organizations have to come up with innovative strategies to safeguard their dependency. This is precisely the situation that many public libraries around the world are currently experiencing. The resource dependency theory holds that organizations frequently put themselves into precarious situations by relying on only one institution or organization to supply vital resources or funds (Hood River County Libraries, 2010). This argument is borne out by the precarious financial position of American public libraries as the contractual relationships they share with other organizations encourage a dependent relationship in which the library relies on state resources for funding (Tkachenko, 2012). This relationship also affects the policies libraries are adopting. Using several measures to explore the impact of diversification on nonprofit institutions, Arawomo, Oyelade, and Tella (2014) found that organizations that have diversified their sources of revenue generally enjoy a better financial position than those that depend on only one source of income.

Limits of the Diversification Theory

Although many of the studies reviewed showed the advantages of diversification, some scholars observed that diversification can also have negative consequences (Arawomo et al., 2014). For example, while firms may improve their financial positions by seeking external funders, they also have to contend with the possibility of meeting the demands of each financier. In an independent study of 172 nonprofit organizations, Tkachenko (2012) observed that financial uncertainties could exist even when diversification entails seeking self-generated revenues. In line with this concern, Lin, Chang, Hou, and Chou (2014) showed that diversification could cause mission displacement because many organizations would be preoccupied with meeting their diversification objectives, as opposed to fulfilling their organizational goals. The possibility of professional elites controlling the organization is also high if firms pursue a diversification strategy (Lin et al., 2014). Overall, many scholars agreed that an organization’s leadership composition, mandate of organization, size of organization, and age of the organization affect the quest to adopt a diversification strategy (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Deborah & Jones, 2009).In fact, with respect to diversification, Alqudsi-Ghabra and Al-Muomen (2012) wrote, “Examining nonprofit revenue diversification is important not only in understanding nonprofit financial management dynamics but also in informing nonprofit financial sustainability” (p. 214). Using data from more than 500 organizations, Deborah and Jones (2009) also revealed that management, investment, and environmental measures affected firm diversification strategies. In a study seeking to find out if revenue diversification improves the financial stability of nonprofit organizations, Paliwal (2013) stated, “Nonprofits can indeed reduce their revenue volatility through diversification, particularly by equalizing their reliance on earned income, investments, and contributions” (p. 6). The positive impact of diversification on financial stability also shows that the modern portfolio theory, which encourages firms to diversify their portfolios, encourages revenue stability and greater organizational longevity.

Organizational complexities and crowding out may impede an organization’s quest to improve its financial stability. Antonios, Olasupo, and Krishna (2010) encouraged the managers of nonprofits to seek additional revenue streams to improve their financial positions. Research conducted by Gholamreza, Ramadili, and Taufiq (2010) showed that older organizations were in a better position to adopt a financial diversification strategy because they had a stronger profile and credibility, compared to younger organizations. Therefore, younger organizations were bound to experience a more difficult time when they seek to attract funders, as they have a weaker legitimacy than their older counterparts have (Gholamreza et al., 2010). The implication of this assessment is that, before new organizations seek alternative sources of funding, they need to build a strong reputation to improve their image in the eyes of potential investors. Then, when potential investors view them as stable and credible organizations, they could get additional funding. Small organizations suffer from similar problems as those that affect young organizations; they also are bound to have a difficult time increasing their revenue streams compared to medium-sized or large organizations (Gholamreza et al., 2010). Large organizations are in a better position to benefit in this regard because their high capacities enable them to pursue alternative strategies for improving their financial stability. Their high recognition within the community also improves their appeal to donors because they are more attractive to investors than small organizations (Gholamreza et al., 2010). In line with this assessment, Paliwal (2013) stated, “Organizations with a broad appeal, that is, those whose mandate resonates with many segments of the population, are more successful in implementing a revenue diversification strategy than are those with narrower mandates” (pp. 8-9). In line with this statement, Deborah and Jones (2009) highlighted the importance of organizations to adopt a revenue diversification strategy that is in sync with their organizational dynamics. In this regard, organizations should consider how and when to choose a revenue diversification strategy that aligns with their size and characteristics. Based on the organizational dynamics highlighted in this document, public libraries need to consider how a diversification strategy would work considering their age, size, history, record of accomplishment, and organizational mandate.

How the Theories Relate to Public Policy and Administration

Public policy and administration spans a wide scope of issues. Coad and Guenther (2014) wrote that key tenets of public policy include “human resources, organizational, theory, policy analysis, statistics, budgeting, and ethics” (p. 857). For a long time, researchers have associated public management with the promotion of the public good. However, the recent public-management dogma has been more concerned with new and market-driven government operations (Coad & Guenther, 2014). Some researchers referred to this view as the “new public management” (Deborah & Jones, 2009. p. 948; Gholamreza et al., 2010, p. 4173). This new view aims to reform government practices by reforming the professional nature of government services. Based on this understanding, public administration theory underscores the focus of this study, which highlights the meaning and purpose of government through its institutions. Here, issues of governance, budgets, and public affairs take center stage (Deborah & Jones, 2009; Gholamreza et al., 2010).

The content of this study appeals mainly to public management dogma, which borrows administrative and functional areas, from the private sector and applies them to public management concepts (Coad & Guenther, 2014). Particularly, this discipline aims to borrow important management tools from the private sector and apply them to the public sector to improve its efficiency and effectiveness. Here, it is easy to show the contrast with the public administration structure, which highlights the social and cultural attributes of the public sector that set it apart from the private sector (Coad & Guenther, 2014). Because the public policy structure is broad, the content of this study will underscore three tenets of the public policy structure: organizational theory, policy analysis, and budgeting. From a budgetary point of view, one might assume that financial stability is the function of a steady and dependable revenue structure, and because public libraries are public institutions, these revenues should benefit the public (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Coad & Guenther, 2014). However, from an administrative perspective, these revenues should also be available to cover administrative expenses such as automation upgrades and revenue shortfalls. By adopting a diversified financial structure, one may assume that no major changes in the library governing structure would occur.

This study will highlight in a comprehensive manner financial management issues that affect public libraries in America. Therefore, the financial management theories reviewed in this study may be useful in supporting these libraries as they conduct their operations in a fiscally responsible way. From a policy perspective, American public libraries should invest library funds in a way that does not infringe on existing statutes, which outline public funds management (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012; Coad & Guenther, 2014). This goal aligns with the objectives of public administration, which focuses on implementing government policies. As a field of inquiry, finding alternative sources of funds to improve the financial stability of public libraries would be useful in improving the functions and goals of public libraries through the improvement of government functions. At the core of this assessment is the study of government decision-making and policy-analysis processes (Alqudsi-Ghabra & Al-Muomen, 2012). The inputs that outline these processes and the work necessary to produce alternative policies would also be useful in understanding this output.

Rationale for Choosing the Theoretical Framework

Francis and Kim (2013) defined a theoretical framework as an analytical tool for understanding a research phenomenon. Effective theoretical frameworks analyze a real phenomenon and analyze it in an easy-to-understand manner, noted the authors. The modern portfolio theory is appropriate for this study because it focuses on social economics. As other chapters of this document will show, this theory is applicable to institutions and companies that suffer from financial problems stemming from undiversified risk (Okojie, 2010). Such is the problem that has plagued public libraries in the United States for some time. Libraries have suffered from budget cuts that have constrained the financial flow from the main, and often the only, source of income: public funding (Hood River County Libraries, 2010). Therefore, the modern portfolio theory provides a framework that could help these institutions to solve their financial predicament. Furthermore, other researchers have applied the theory in similar contexts quite successfully (Alqudsi-Ghabra and Al-Muomen, 2012). For example, financial experts have applied the theory in different project portfolios (Okojie, 2010). Its application has also stretched to nonfinancial disciplines, including regional science and social economics as applied in this study (Cross, 2011). Some researchers have used the portfolio theory to explain labor movements in America (Cross, 2011). Some of Cross’s (2011) work has also applied the theory to explain the relationship between economic growth and economic instability. Recent applications of the modern portfolio theory have stretched into psychology and the modeling of correlations between documents when retrieving information (Okojie, 2010). The purpose of doing this was to increase the relevance of a document, while reducing the associated uncertainty of getting irrelevant information. Overall, these applications showed that the theoretical framework is reliable in many social and economic contexts. This justifies its use in this study.

The resource-based view is an alternative concept that explains the need for corporate diversification (Armstrong, 2010). This view underscores the need to diversify as a strategy for companies and institutions to exploit their core competencies (i.e., resources). Usually, companies that pursue this strategy aim to explore their “excess capacity” by deploying resources that are imperfectly tradable in the market (Armstrong, 2010). Proponents of this view developed it as a concept for explaining the need to seek alternative businesses (Armstrong, 2010). However, scholars started to appreciate its use in the 1980s as an instrumental tool for explaining synergies and economies of scale (Armstrong, 2010). Andissac et al. (2014) argued that for companies to apply the resource-based view, they should have trouble exchanging their resources in the market. This strategy aligns with the assertions of Francis and Kim (2013) and their views on transaction-based economics. Researchers have used this concept to explain horizontal and vertical diversification strategies in the past (Francis & Kim, 2013).

Critique Leveled at the Modern Portfolio Theory

Opponents of the modern portfolio theory advance their criticisms of the theory based mainly on behavioral economics. For example, Alqudsi-Ghabra and Al-Muomen (2012) questioned whether the theory outlines an ideal investment strategy. The authors believed that, although the theory is widely applicable in financial circles, it does not necessarily apply in a real-world setting. The efforts of some statisticians who have tried to translate the theoretical components of the theory into a practical algorithmic formula have affirmed this concern (Okojie, 2010). In the process, they have experienced significant challenges, which stemmed from the technical problems associated with unavailable data (Francis & Kim, 2013). However, proponents of the modern portfolio theory affirmed that including a penalty would solve this problem (Francis & Kim, 2013). Aside from these main criticisms leveled at the modern portfolio theory, people have often criticized the model for its expansive assumptions.

The first assumption of the modern portfolio theory is that all investors are interested in maximizing their returns (Francis & Kim, 2013). However, the theory’s critics argued that, pragmatically, this may be false in that utility function often vary across a given range (Francis & Kim, 2013). In this respect, Okojie (2010) believed that the theory has a flawed assumption on returns. The second assumption of the modern portfolio theory stems from the efficient-markets hypothesis, which states that all investors are rational and risk averse (Francis & Kim, 2013). However, the theory’s critics contended that some investors are irrational when making financial decisions (Cross, 2011). Furthermore, they believed that even rational investors often do not display this behavior (i.e., rationality) consistently (Cross, 2011). Another disputed assumption of the modern portfolio theory is that transactions have no tax consequences or transaction costs (Francis & Kim, 2013). Here, the theory’s critics argued that most real products are taxable and have an associated transaction cost (Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). Furthermore, they asserted that these costs, in fact, change the performance of every portfolio analyzed (Cuillier & Stoffle, 2011). Last, the modern portfolio theory assumes that all investors predetermine the risks and understand them in advance (Francis & Kim, 2013). However, critics of the modern portfolio theory believe that most experts miscalculate these risks, as seen in the recent 2007/2008 global financial crisis and the economic turmoil that affected most European economies over the last decade (Andissac et al., 2014). Here, researchers have used the theoretical framework to make distinctions about supply-and-demand forces and their effect on the behavior of consumers and companies in the market. In this study, the theoretical framework will help to organize different ideas that emerge in the course of the research. Furthermore, its application provides a model for addressing some of the inherent challenges and gaps created by the failure of public institutions to adopt mainstream corporate strategies to improve their financial performance.

This study will contribute to the development of the modern portfolio theory because there are currently no systematic methods for portfolio selection and financial diversification in the public library finance management field. Most of the researchers who have used the modern portfolio theory have mainly shown how it would apply to organizations that are free to diversify. Comparatively, they have paid little attention to those that have poor structural designs to accommodate such a strategy (financial diversification). Public libraries are such institutions because their operation structures do not openly accommodate financial diversification (compared to private entities). Since this study focuses on CCLS, which is a public organization, the findings of this study will contribute to the growing body of knowledge surrounding diversification in the public sector. This is the main contribution of the study to theory development in this sector.

However, to understand the study’s contribution to theory development, it is pertinent to understand the nature of public libraries as the focus of this chapter.

What are Public Libraries?

Public libraries differ from other types of libraries because they offer their services to all types of people in a nondiscriminatory manner. Wells (2014) stated that there are more than 16,000 public libraries in the United States, which depend on state funding to provide their services. These libraries have unique characteristics that set them apart from other types of institutions. For example, an appointed board manages the activities of these libraries and makes sure they serves the public interest before any other concern (Kim, 2011). Another characteristic is open access, that is, anybody can use these libraries. This characteristic closely aligns with the third characteristic of public: the voluntary use of its services (Wells, 2014). In other words, the government does not coerce library users to use these services. Last but not least, these libraries provide free services. Based on these characteristics, public libraries have limited options for getting financial means.

The American Library Association (2013) wrote that public library administration generally occurs at county, state, or local levels. In the United States, many cities have at least one public library, but in outlying areas, county administrations may provide library services. State libraries are often the main repository of the information contained in these public libraries. The 50 states of the United States of America have similar structures for managing public libraries; however, their organizing principles may vary. The next section outlines the different organizational structures that shape their operations.

Organizational Structure of Public Libraries in America

Similar to the structural diversity of modern businesses, public libraries have different administrative structures that define how organizational processes are carried out. Thomas (2010) wrote that the typical organization structure of a public library consists of three elements: public services, technical services, and administration. Public services refer to front office staff that interacts with the customers. The technical level comprises employees or groups of professionals who work behind the scenes to prepare materials for the clients (Dukić & Dukić, 2014). The administration level makes sure that the library’s activities align with the goals or vision of the parent organization (American Library Association, 2013). However, for public libraries, the administrative structure often makes sure that the organization’s activities align with county goals as well. Table 1 summarizes the functions of each of the structural levels of a public library.

Table 1: Functions of the Structural Level of Public Libraries

This chapter concentrates mainly on the roles played by the administrative services division of public libraries. Library administrations usually oversee the financial operations of public libraries. However, before discussing these operations, it is important to understand the background and history of public library funding in America.

Background and History of Public Library Funding in America

The history of public library funding in the United States traces its roots to the first establishments of public libraries, in 1656 (Harris, 1995, p. 182). Historians documented that a Boston merchant, Robert Keayne, was among the first to make his books available to the people for public use (Harris, 1995, p. 182). He used mainly his own money to finance the operation. Other historians believe that Benjamin Franklin started the first public library in America, in 1731 (American Library Association, 2013). The variations in the dates depend on the definition of the term public library and the types of services offered by these institutions. However, the proliferation of public libraries in America stems from the work of the Scottish-American philanthropist, Andrew Carnegie (American Library Association, 2013). He financed more than 2,000 public libraries in the country. His philanthropic work started in 1889 when he built his first public library. Since then, more than 16,000 public libraries have been built in America (American Library Association, 2013).

Although individuals financed public libraries during the 19th century, the church quickly joined this movement and started to make books available to the public (Harris, 1995). Their sources of funding came mainly from well-wishers. Kingdom Chapen Library in Boston, Massachusetts, was among the first establishments funded by donations of well-wishers from Europe (Donnelly, 2014). Between 1695 and 1704, the Catholic Church established more than 70 public libraries in some former colonies in what is now the United States of America and financed them by the same methods: donations and gifts from well-wishers (Harris, 1995). In 1731, a new model of library funding took root in the colonies: subscription funding (Black, 2011). This model of funding charged users a fee for borrowing books. It was started by Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia (Harris, 1995).