Introduction

Today’s economic services corporations perform countless contracts and business functions through public and confidential computer systems that create new and compound risks, comprising computer security contravenes, information theft, extortion and business interruption due to a virus, worm, malicious code or hacker attack. Regardless of the level of IT security in place, today more than ever financial services companies are under constant threat of network security breaches and exposed both legally and financially. Network security risks can significantly affect a company’s shareholder value, corporate stability, credibility, reputation and financial performance. As such, it’s important for boards to play an active role and take direct responsibility in building comprehensive security measures to safeguard their valuable digital assets. As affirmed by a well-respected task force report entitled “Information Security Governance: A Call to Action”, information security should not be treated solely as a technical issue; but instead, be elevated “from a CIO-level issue to one managed by the CEO and the board of directors.”

Identification of risks

The first option available to financial institutions that wish to transfer personal data from the European Union to the United States is to submit individual contracts to European data protection authorities for review and approval, However, this process can be difficult, if not impossible, to comply with on an ongoing basis and raises issues of business confidentiality. Ambassador Aaron has stated that one U.S. multinational told him “that if they took that route, they would have to negotiate over thousands of such contracts.” Nevertheless, some firms are using this approach, while others “piggyback” on these firms’ efforts by using contracts similar to those already approved.

Recognizing the cumbersome nature of individual contract review, the European Union has promulgated two “model contracts” under the terms of which data may be lawfully transferred out of the European Union to ah organization located in a country that does not provide an adequate level of privacy protection–one covers pure transfers of data to third countries, while the other governs arrangements in which a company subcontracts data processing operations to a firm located abroad. The second model contract provides for less stringent safeguards because transfer to a processor entails less risk in that a processor acts exclusively on behalf of the controller and has no independent rights or interest in the information. The banking industry considers these model contracts to be the “only… streamlined option” currently available. However, the provisions of the contracts are extremely problematic.

Under the first model contract, the data exporter agrees:

- to handle the data in accordance with the relevant data protection law of the exporter’s EU Member State;

- to inform the data subject of the potential transfer if the transfer involves special categories of data;

- to make a copy of the contract available to the data subject; and

- to respond to inquiries from the relevant supervisory or from the data subject.

In turn the data importer agrees and warrants:

- that he has no reason to believe that any law prevents him from fulfilling the contract;

- to process the data in accordance with stated principles;

- to deal promptly with all reasonable inquiries from the data exporter or data subject;

- to submit to an audit at the request of the data exporter;

- to make a copy of the contract available to the data subject and indicate the office that handles complaints.

The parties to the model contract agree to be jointly and severally liable to a data subject for any violation that causes harm to the data subject; the data subject may bring suit in either the jurisdiction of the data exporter or that of the data importer. A data subject can also invoke the contractual clauses as a third party beneficiary In that event, the parties must agree to abide by the decision of the data subject to resolve the dispute either through mediation or by reference to the courts of the data exporter’s Member State.

The second model contract offers similar liability and jurisdiction provisions, allowing an aggrieved data subject to elect resolution of the dispute either by mediation or before the courts in the Member State of the data exporter. Among other provisions (generally similar to those of the first model contract), the foreign data processor must agree to process the data only on behalf of the data processor and to implement mutually-agreed upon technical and organizational security measures.

Risk is a measure of the degree of uncertainty associated with the return on one asset relative to an alternative asset. This four day intensive module will focus on understanding all aspects of risk associated with interest rate from both an investors’ point of view and the MFIs, including the real cost of capitalization.

Through lectures, case studies and examples we will examine the opportunity cost of alternative capitalization strategies to international donor agencies, and to private and public sector entities that are actively engaged in funding microfinance institutions (MFIs). We will also focus on the currency risk exposure faced by foreign investors and MFIs when the original investment or capital originated in a hard currency. We will take a look, for example, at the risk associated with the $106m USD bond backed by loans to 22 MFIs, issued in early 2006 by BlueOrchard, a Geneva-based specialist company.

Other topics will include inflation and its impact on capitalization (nominal vs. real interest rates), liquidity risk management (the ease and speed with which an asset can be turned into cash), the impact of a local government’s budget deficit on the interest rate equilibrium, and the risk of default and associated risk-related premium. We will conclude the session by calculating the risk premium and the real cost that MFIs face in financing loans to their clients.

Now, world financial community faces various regulatory requirements and movements that require more agile, efficient accountability. Although it’s often specific regulations that are triggering the improved agility, accountability and efficiency, companies find benefits – such as improved ability to manage customers – that extend far beyond meeting those regulatory requirements. There definitely is more complexity to how we do business today, such as a wide variety of customer communication channels, which forces companies to seek a 360-degree view of their customers. If companies don’t tie those channels to a holistic view of their customers, then they’re unduly exposing their organization to risk. Of course, there are many anecdotal stories about how a financial institution’s most profitable customer wasn’t handled properly in one branch of the business because that branch didn’t know the customer’s full spectrum of interactions with the institution, and thus didn’t know the customer’s true value – for example, not knowing that the customer is a highly valued investor at the institution, the loan area might not handle the customer properly and thus lose the customer. To add a historical perspective to this discussion, the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s was a wakeup call that weak governance, poor systems, and poor risk assessment practices in financial institutions could no longer be tolerated. If I may quote from a report by the International Monetary Fund: The crisis unfolded against the backdrop of several decades of outstanding economic performance in Asia, and the difficulties that the East Asian countries face are not primarily the result of macroeconomic imbalances. Rather, they stemmed from weaknesses in financial systems and, to a lesser extent, governance. A combination of inadequate financial sector supervision, poor assessment and management of financial risk, and the maintenance of relatively fixed exchange rates led banks and corporations to borrow large amounts of international capital, much of it short-term, denominated in foreign currency, and unheeded. As time went on, this inflow of foreign capital tended to be used to finance poorer-quality investments.

The biggest risk in the regulatory area, of course, is the failure to comply. Financial institutions must have systems in place to manage credit and operational risk to the satisfaction of regulators, or they won’t be around for long. The quasi-public nature of financial institutions demands this. As to customer interaction, there are, as I mentioned when we started talking at the beginning of the interview, many add-on benefits from mitigating regulatory compliance risk, including greater agility in meeting customer needs as well as greater ability to have a 360-degree view of customers, both of which drive up customer satisfaction.

Interest rate risk

It is the risk that the relative value of an interest-bearing asset, such as a loan or a bond, will worsen due to an interest rate increase. In general, as rates rise, the price of a fixed rate bond will fall, and vice versa. Interest rate risk is commonly measured by the bond’s duration, the oldest of the many techniques now used to manage interest rate risk. Asset liability management is a common name for the complete set of techniques used to manage risk within a general enterprise risk management framework.

Senior management is responsible for ensuring that the bank has adequate policies and procedures for managing interest rate risk on both a long-term and day-to-day basis and that it maintains clear lines of authority and responsibility for managing and controlling this risk. Management is also responsible for maintaining:

- appropriate limits on risk taking;

- adequate systems and standards for measuring risk;

- standards for valuing positions and measuring performance;

- a comprehensive interest rate risk reporting and interest rate risk management review process;

- effective internal controls.

Companies carry credit risk when, for example, they do not demand up-front cash payment for products or services. By delivering the product or service first and billing the customer later – if it’s a business customer the terms may be quoted as net 30 – the company is carrying a risk between the delivery and payment.

Significant resources and sophisticated programs are used to analyze and manage risk. Some companies run a credit risk department whose job is to assess the financial health of their customers, and extend credit (or not) accordingly. They may use in house programs to advise on avoiding, reducing and transferring risk. They also use third party provided intelligence. Companies like Moody’s and Dun and Bradstreet provide such information for a fee.

For example, a distributor selling its products to a troubled retailer may attempt to lessen credit risk by tightening payment terms to “net 15”, or by actually selling fewer products on credit to the retailer, or even cutting off credit entirely, and demanding payment in advance. Such strategies impact sales volume but reduce exposure to credit risk and subsequent payment defaults.

Credit risk is not really manageable for very small companies (i.e., those with only one or two customers). This makes these companies very vulnerable to defaults, or even payment delays by their customers.

The use of a collection agency is not really a tool to manage credit risk; rather, it is an extreme measure closer to a write down in that the creditor expects a below-agreed return after the collection agency takes its share (if it is able to get anything at all).

Calculating risk scenario

Once the inputs have been entered and selections made in the Risk Management Toolbox, harvest-time “What if?” scenarios can be conducted. The two levers at this stage are the harvest futures price and the harvest yield. Any value for both may be selected and the calculator determines gains or losses from the chosen strategies. The result on the bottom line is revenue net of risk management costs. That revenue level can then be compared to the enterprise budget for the crop.

The first item in the scenario is “Cash”, computed as the sum of harvest futures price and basis times the harvest yield. Cash is intended to match the price at a local elevator. Next are the gains or losses from insurance tools. For both product types indemnity payments are computed based on harvest yields, then the cost of the insurance is subtracted, leaving the indemnity net of the premium.

The net gains from marketing tools are then computed. “Hedge” refers to futures results. Note that basis is constant, so it does not influence gains and losses here. “Puts” and “Calls” refer to the net gains from buying the respective tools. If harvest futures price result in intrinsic value in the options, the gains are computed and the initial premium is subtracted. Hence, only in-the-money options at harvest have value.

The final adjustment to revenue is any LDP payment computed at harvest. If the sum of the harvest futures price and basis is less than the loan rate, the difference is multiplied by harvest yield to obtain an LDP payment per-acre. The various risk management adjustments are added to the cash price to obtain the “Revenue”.

This approach is very simple and intuitive. However, the capital loss effect that is measured by both the maturity and duration models and not taken into account in the repricing model, assets ad liability values are reported at their historic values or costs. Thus, interest rate changes affect only current interest income or interest expense – that is, net interest income on the financial institution income statement – rather than the market value of assets and liabilities on the balance sheet.

The financial institution manager an also estimate cumulative gaps (CGAP) over various repricing categories or buckets.

Risk calculation ad analysis provides an intuitive, easy-to-use interactive graphical user interface for designing complex Risk scenario models. Models are initialized using analysts’ best guesses about individual Risk factors. Risk calculation ad analysis algorithmic simulations use these initialized models to create a set of what-if scenarios. The results of these what-if scenario simulations can be exported as re-ports to MS Office, for example.

Manually assessing and quantifying interactions of different Risk factors is a laborious and notoriously error prone task. Merge flow‘s risk calculation ad analysis software uses novel inference algorithms to accomplish this task. This allows users to generate more realistic and accurate models in less time.

Risk calculation ad analysis also provides methods for showing differences and similarities between different Risk models. Analysts can compare their models, and immediately identify divergences or commonalities between their models. They can also share models, or incorporate parts of their colleagues’ models in their own models.

It is important to note that the calculation of the vulnerability strongly depends on the stochastic meteorological conditions. Instead of considering only the worst or the most probable condition, we introduce distributions for wind direction, wind velocity and atmospheric stability. Then, the Monte Carlo simulation is used to obtain the concentration distribution for each receptor. Consequently, the total risk involves the whole relevant information about the problem. In fact, the whole set of scenario possibilities is covered for the calculations.

To calculate the risk scenario, it is necessary to apply the following formula:

Yt=f(Zt)+et

where Yt denotes the observation of the dependent variable at time t, the vector Zt comprises the observations of the explanatory variables at time t, and e t is an independently and normally distributed error term with mean 0 and constant, finite variance

Conclusion

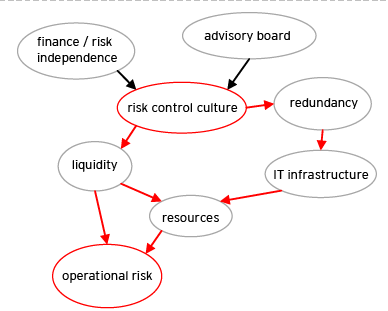

As financial services firms adopt new product lines, enter new markets and lose the protection of traditional industry barriers, managing risk has become a major concern. In today’s financial markets, many firms offer products and services that cross what had once been traditional boundaries. As a result, they must now manage default, interest-rate and market risks as well as risks associated with liquidity and operations.

To address such wide-ranging risks, financial services firms now require new business practices in order to control, transfer and profitably manage the broader risks they now regularly assume. To help identify those practices, the Center has sent faculty researchers and doctoral students into the field to analyze the current risk systems of commercial banks, investment firms and insurance companies.

Financial risks are referring to financial instruments. Alfa Laval has the following instruments: cash and bank, deposits, trade receivables, bank loans, trade payables and a limited number of derivative instruments to hedge primarily currency rates or interests, but also the price of metals. These include currency forward contracts, currency options, interest-rate swaps, interest-forward contracts and metal forward contracts.

In order to control and limit the financial risks, the Board of the Group has established a financial policy. The Group has an aversive attitude toward financial risks. This is expressed in the policy. It establishes the distribution of responsibility between the local companies and the central finance function in Alfa Laval Treasury International AB, what financial risks the Group can accept and how the risks should be limited.

References

- Culp, C. L. (2001). The Risk Management Process: Business Strategy and Tactics. New York: Wiley

- Harwood, A., Litan, R. E., & Pomerleano, M. (Eds.). (1999). Financial Markets and Development: The Crisis in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Jones, C. V. (1991). Financial Risk Analysis of Infrastructure Debt: The Case of Water and Power Investments. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

- Nersesian, R. L. (1991). Computer Simulation in Financial Risk Management: A Guide for Business Planners and Strategists. New York: Quorum Books.

- Tallman, D. A. (2003). Financial Institutions and the Safe Harbor Agreement: Securing Cross-Border Financial Data Flows. Law and Policy in International Business, 34(3), 747