Introduction

Although it is not an indigenous crop, maize is a very important staple food in Kenya. Kenyans consume large quantities of maize either as whole or sifted. Whole maize may be roasted, boiled, or may even be used to make common relishes. (Kamau, 2002) On the other hand sifted maize is mainly used to make Ugali, a very common meal found on the table of every Kenyan. It can therefore be seen easily that maize has a high demand in this country. This is especially true with an increasing population that has been maintaining the tradition of retaining maize as an important staple food. Most of the maize that is consumed in Kenya comes from domestic farmers. However, faced with diverse difficulties, domestic production of maize has been dwindling amid an increasing demand hence creating a need for occasional importations to supplement domestic production. (Kamau, 2002)

A common trend that has been emerging not only in Kenya but in other countries as well as the increasing value and importance of services associated with agricultural goods. These take a larger share of revenues earned from consumers denying farmers a considerable proportion of earnings. This even applies more in the case of sifted maize which undergoes several stages of preparation including processing before finding itself in the retail chain for buying. While both sifted maize and whole maize require marketing services, sifted maize is considerably marketed through common brands available to consumers. Some consumers may however seek milling services from local milling centers where they pay some money to obtain milling services. Whole maize on the other hand is mostly available in open-air markets where it is ferried from farms to these markets for buying. No companies are offering this kind of service, it is mainly done by thousands of local entrepreneurs. (Mukumbu & Jayne, 1994)

Generally the following are important agents in the maize value chain network in Kenya. First, we have producers who include both small and large-scale farmers in Kenya spread over different regions. Most of the supply however comes from the northern region of Rift valley province in the country. Assemblers on the other hand mainly work to collect maize from farmers for distribution to millers. Assemblers may consist of individuals or even organizations, some of which have special means of storage for durability. While assemblers are mainly found in high production areas, we also have another category of actors that can be referred to as dis-assemblers who are mainly found in scarce producing regions. The function of these disassemblers is mainly to collect maize from assemblers and supply it to millers or even retailers. The function of the millers on the other hand is to provide milling services, packaging services and marketing services through their brand name. Wholesalers come between millers and retailers to store and supply sifted maize products to retailers. The maize flour product can now go to the retail chain for sale to consumers. (Mukumbu, 1995)

This study intends to find out the marketing margins accruing to various actors in the Kenyan maize value chain and how these have been changing over time (1995-2009). It is important to note that this is a period after which the maize sector in Kenya had been liberated. (Jayne, 1995) The main motive behind liberation of the maize sector in Kenya was to encourage investment and create competition something that would in the end benefit both the consumer and the producer. Ironically, the result of liberation has almost been contrary to expectations. Investment especially by millers has been done by a few players who have been accused of collaborating to control the market and even blackmail other actors including the government. Although prices have been considerably increasing damaging the pocket of consumers, farmers’ earnings have been dropping at an increasing rate. The current trend that has evolved in the exploitation of farmers by assemblers, who offer ready but little money to farmers after harvesting and the exploitation of consumers by millers and other actors on the other hand who sell their products at inflated prices. (Thomas & Pinckney, 1999)

Problem Statement

There are unfair discrepancies in earnings among various actors in the maize chain value in Kenya something that is leading to exploitation of some players including farmers who are forced to accept inadequate payments for their products and consumers who have to pay inflated prices for maize products highly damaging the maize sub-sector in the process. There is therefore a need to minimize the gap of these discrepancies through any possible remedies that can be developed through the cooperation of farmers, government support and support from other relevant parties to salvage the important but ailing maize sub-sector in Kenya.

Research Objectives

- To find out existing discrepancies in earnings by various actors in the Kenyan maize value chain

- To find out how these discrepancies have been evolving and changing in the Kenyan maize value chain in the period from 1995-2009.

- To find out the causes of these discrepancies by various actors in the Kenyan maize value chain.

- To find out possible solutions that can be applied to reduce marketing margins accruing to various actors in the Kenyan maize value chain

Hypothesis

Minimizing unfair discrepancies in marketing margins by various actors in the Kenyan maize chain value will salvage the ailing but important maize sector in Kenya.

Research Questions

The first research question will be used to determine the profit margin accrued by various actors in the Kenyan maize chain value. This research question will target farmers, wholesalers, assemblers and other actors in the Kenyan maize chain vale.

What is the profit margin accrued by various actors in the Kenyan maize chain value?

The second research question will be built on the first research question. Addressed to the same audience, it will seek to find out how the trend of earning on the part of farmers and other actors has been changing while that of spending on the part of consumers on the other hand has also been changing.

How have profit margins by various actors in the Kenyan maize value chain been changing since 1995-2009?

The third research question will seek to find out why farmers are selling their produce at low prices,

Do farmers sell their produce at low prices because they have not been helped to access the market effectively?

The fourth research question will intend to find out solutions that can be implemented to minimize unfair discrepancies in Kenyan maize chain value:

Which solutions can be applied to shield the consumer and the farmer from exploitation while promoting the Kenyan maize sector?

Justification of the study

While maize remains an important staple food in Kenya, the sector is increasingly facing several challenges. The main threat to this sector is the continued exploitation of the Kenyan maize farmer who is forced to sell their produce at a considerably low price and the Kenyan consumer who is forced to buy maize products at an inflated price. On the other hand many small retailers are making very little earnings from the sale of maize products. It is the middlemen and millers who take a lion’s share of earnings from the maize chain value although their input can arguably be considered low as compared to farmers and even small retailers. This scenario is creating several problems not only in the maize sector but to the Kenyan economy itself. First, there is an increasing shortage of maize in the Kenyan market which is a direct result discouragement of farmers who can not show for their work in terms of earnings. This is likely to compromise food security in the country as it increasingly moves from self-reliance on maize to importation. This problem is even compounded further considering that Kenya is a developing country with several inherent problems that can easily interfere with maize importations. For example, the government does not have an effective network of determining the stocks of available maize in the country something that has created imminent shortages and scares that have led to skyrocketing prices.

Even when arrangements are made for quick importation, there is normally an element of considerable poor planning and preparation. The situation has been quite grave considering that in some cases, imported maize has been found out to be unfit for human consumption. With elements of corruption quite active in Kenya, this maize has even found its way to customer shelves greatly compromising the health of Kenyan citizens. Moreover, there is the concern of increasing piracy from neighboring Somali pirates. These have at times taken hostage ships that contain grains including maize which may be imported for local consumption. All these emphasize the need for Kenya to be self-reliant on maize something that can only be guaranteed if the farmer and other important players are allowed to benefit. Besides, by denying the farmer a fair share of earnings and by exploiting the consumer and other actors in the Kenyan maize value chain, poor economic distribution is even enhanced perpetuating poverty in Kenya even further. Moreover, I think that the interests of actors like millers and even middlemen are in danger in the long run. This may especially happen with a dwindling production from farmers and a diversification of meals by consumers as an approach to dealing with increasing prices of maize products. (Owuor, 2009)

This research is intended to provide data that would help in addressing the various issues that I have raised to salvage the maize sector which is important to the Kenyan economy and its people. The Kenyan government and interested parties would find my recommendations that would be based on strong support from my findings useful and will therefore help them to implement appropriate reactions and policies. Careful consideration of issues that have led to unfair distribution of market margins in the Kenyan maize chain value will show that when this problem is solved, all players in the value chain are bound to benefit. The economy is even likely to benefit from such actions expanding the Kenyan maize market as the spending powers of Kenyans that are reaping the benefits of an expanding economy expand.

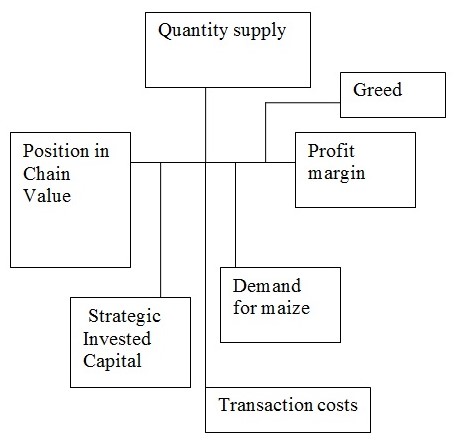

Theoretical framework model

The above model will be used in the study. It contains different variables that determine profit margins in the Kenyan maize value chain obtained by various actors. One of these variables is the position of an actor in the Kenyan maize chain value. By virtue of their position in the chain value, some actors are bound to make more profit margins than others. Millers and middlemen for example make more profits considered to farmers and retailers. Another parameter that determines profit margins by actors in the Kenyan chain value includes the amount of capital that has been strategically invested. This may apply when a farmer for example may invest a considerable amount of money in storage enabling him to store his/her produce for considerable time after harvest and thus sell at a higher price when the supply has decreased and demand has increased.

Of course, maize demand determines the profit margins that are obtained by various players in the Kenyan maize value chain. When there is a high demand for maize as it is currently the situation especially with an increasing population, the prices of maize tend to go high increasing profit margins for some players. However, there have been complaints that these increased earnings are not passed on to other actors like farmers or even retailers. This brings us to another very important parameter that applies in the Kenyan maize value chain-greed. There has been visible greed on the part of some players in the Kenyan maize value chain most notably by millers and middlemen. These have been accused of exploiting farmers and consumers. Although their profit margins are very high, the same does not apply to other important players like farmers and small retailers.

Supply also affects profit margins by several actors in the Kenyan maize supply value chain. Consumer end prices have been significantly affected by supply. Low supply leads to high consumer prices and high supply leads to low consumer prices. Once again, the power of millers and middlemen is seen at play here. They have the capacity of creating artificial shortages to exploit consumers and even import maize to create artificial high supplies to exploit farmers.

Another important parameter that determines profit margins accrued by various players in the maize chain value in Kenya is transaction costs. These include costs incurred in market research, in making deals and also in making and maintaining contracts among similar costs. These are mostly incurred on a large scale by big actors in the chain value like millers, middlemen (assemblers) and wholesalers.

Literature Review

The issue of differences in profits margins has been of interest to many groups and individuals. This is especially true considering the impact of the current scenario in the maize sector on farmers, consumers, food security and other important areas. Several studies relating to the issue of differences in profit margins accrued by various stakeholders in the Kenyan maize value chain have been carried out by various researchers.

Nyongesa, Lutta and Muriithi carried out a study on the determinants of maize seed pricing in Kenya using a value chain approach. (2004) The objective of their study was to find out how the price of seeds has affected the use of certified seeds by Kenyan farmers. Data obtained for this study was mainly primary data obtained from at least thirteen different district areas in Kenya. During the study, the analysis of value chain was used to find out the costs involved in the production of maize at various stages where production is conducted. At each stage of production, chain actors were identified and their roles and relationships were noted.

Following their study, they came up with the following results. First, that there are both formal as well as informal channels that supply seeds. These channels consist of both individuals as well as organizations. It is from these channels whereby maize seeds move from one chain to the next chain. Secondly, they noted the following areas to be the major producers of maize crop in Kenya namely Baringo, Uasin Gishu and Nakuru Districts. (Nyongesa, Muriithi & Lutta, 2004) They also discovered that on average, every farmer in these regions tills about forty-two acres of land. According to their study, fertilizers and pesticides formed the largest component of costs at about 25% followed closely by the cost of preparing land at about 11%.

Research by the above group was centered on finding out the following. First, whether cost charges by various players in the maize chain value marketing systems are in a consistent manner. Secondly, whether there are enough players to ensure that there is sufficient competition would in turn assume that costs will automatically spiral to lowest levels. To carry-outs their study in this fashion, they used an (SCP) typical structure performance analysis to evaluate the market in terms of the above two conditions that I have mentioned. According to this structure, as a market shifts further from the idea of a perfect competition, competitiveness in the market is bound to decrease something that would prevent market efficiency. (Scarborough & Kydd, 1992)

During their study they considered some factors at play that would influence their results. One of these factors was the realization that as much as marketing margins can be used to obtain the approximate value of costs; these costs tend to be quite high and may also be unstable such that they may discourage investment in the system of marketing something that would fail to promote farm productivity. These limit assessing the performance of markets basing on whether costs can be used to give an approximate marketing margin. This is because long-term issues on how incentives can be incorporated into the rules of economic exchange with an aim of reducing incurred costs at diverse stages in the marketing system are ignored. (Jayne,1997)

Another challenge that was considered is that of finding out whether there is perfect competition in the Kenyan maize marker considering economics of scale. In this specific market, economics of scale are likely to be seen from the presence of very small markets and also from the use of technology. A good example of this is seen whereby due to the high costs of transport, maize products are likely to be more expensive at targeted markets due to transportation costs as compared to regions where production occurs. A result of this scenario is a limited number of assemblers in production areas due to limited surplus quantities available in production regions as a result of low prices. This is especially true with scale economies involved in marketing like transportation costs for example. In this scenario, the presence of a limited number of assemblers can not be used to verify the existence of a non-competitive market.

Finally, another challenge that was considered is the fact that market size limits the capacity of maize in specialization as well as from commercialization. Costs incurred during transactions limit market size. Among the costs that are involved here include costs used to negotiate a deal, costs that are used to collect data which would then determine if it is profitable to engage in business, contractual costs among others. Noting that the costs of transactions in this market are considerably high, it is important to put these into consideration when determining profit margins and not just the value of exchange from one actor in the chain value to another.

Data that was used in this study includes primary data that was obtained from visits to 1540 households in rural areas which were carried out in the month of April 1997 (Argwings, 1998) as well as primary data from some actors in the maize chain value market in Kenya. Among actors that were interviewed in this study include assemblers, retailers, millers and wholesalers. Data was also collected from Nairobi region, a major market of maize products in Kenya.

Their study showed that in general, market margins have been reducing since the liberation of the maize sector in Kenya especially between surplus and deficit areas in the country. Thus, buying prices for consumers found in deficit areas have almost equaled buying prices for consumers in surplus areas. Another finding of this study was that in general, the trend was an increase in the margins for miller retailer margins. As of 1998, the miller retailer margin was found to be about 9.30 Kenyan shillings per one kilogram. This margin includes costs of distribution from millers to retailers and also considers the marked selling price by retailers. On the other hand, profit margins accrued by farmers were shown to be on a downward trend in general while milling margins for large-scale milling had not changed considerably as at 1998. Besides, the study was able to show that as of 1998, there was a general decrease in the amount of maize production by farmers. Most farmers were shifting to other farming activities including dairy farming that was more profitable.

Owuor carried out a study in Kenya in 2009 on the problems troubling the maize sector in Kenya. This was a study that was used to follow up on one that had been conducted earlier on who exactly was getting the money from high food prices by Heinrich Bill Foundation. This study was relevant at a time when maize prices were increasing at unexplainable rates in the country. The purpose of this study was to consider the Kenyan government’s reaction to the maize crisis including subsidies and waivers on maize duty intended to bring down costs as well as consider proposals for the maize sector including the Kenyan national cereals and produce board.

This study found out that the costs of seeds and fertilizers were considerably high for farmers that even when the government moved into subsidy costs, the process delayed so much such that most farmers obtained these supplies quite late when planting had already progressed. Moreover Owuor found out that due to the failure of crops it was likely that the prices of maize would continue to be high for a considerable time to come as a result of decreased supplies. (KARI, 1995) Another finding was that most Kenyans had a feeling that the policy of duty waiver imports by the government was not bearing any fruits to reduce prices and that there was an elaborate network of corruption at play to even exploit the consumers further through these imports. (KEPHIS, 2003)

Moreover, Owuor showed that there is a general inefficiency by maize farmers in Kenya. According to his analysis, he showed that in Kenya, an inefficient farmer will use about 1,684 Kenyan shillings to produce one bag of maize while an efficient farmer on the other hand will use about 1, 312 shillings to produce one bag of maize. Considering that South African farmers use as much as twice the amount of fertilizer used by an efficient farmer in Kenya to produce an average of 55 bags of maize per acre compared to 20 bags per acre produced by an efficient farmer in Kenya, the average cost of production by the south African farmer per bag is significantly low. This explains why maize produced in Kenya is considerably expensive.

Kodhek and Jayne carried out a study on how Kenyan maize consumers in urban areas have responded to the liberalization of the maize market. Their research relied heavily on data obtained from two random sample surveys that were conducted in Nairobi on two different occasions. To carry out reliable analysis for the purposes of the study, two changes in the price of maize were considered. One, changes in the price of whole maize in grain form were considered. Secondly, changes in milling/ retailer margins were also considered. In their study they defined milling margins as the difference in the price of maize grain bought by millers and retail price of sifted maize putting into consideration the removal of processing rates and value addition among other costs by millers. (Scott, 1995)

According to their findings, they showed that following the liberalization of the maize sub-sector in Kenya, low-income earners’ consumption of sifted maize decreased considerably. A trend that was observed was that while high-income families spent a lot on sifted maize, low-income families preferred whole maize to minimize costs. This is especially true with the increasing investments in local small milling centers. These have tremendously increased in number since the liberalization of the maize sub-sector. (Bagachwa 1992; Tschirley and Santos 1994; Mukumbu 1995; Rubey 1995).

Methodology

Introduction

Development of a research topic and objectives was the first stage in carrying out this research. Once this was done, I developed a detailed research proposal that allowed me to consider related research that has been done by other parties. This equipped me with necessary knowledge that would then guide me in my research. Collection of data would then be the next important stage in my study. Care has been given to ensure that obtained information is as accurate as possible. Once this has been done, I will use statistical techniques to analyze obtained data so that I can represent it in the desired format where I can establish relationships between profit margins accrued in the maize chain value by different actors in the period 1995-2009. The final step would represent my findings in a report format for use by relevant parties.

Research design

For purposes of this study, I would use a quantitative research design. I will establish the relationship of varying parameters in my sample population with the dependent variable which in this case is amount of accrued profit margins in the maize sub-sector by an actor in the Kenyan maize chain value. These actors will include assemblers, dis-assemblers, maize farmers, wholesalers and retailers. All of these would then be given attributes/ variables described in my model which would then be used to determine the dependent variable (proportion/quantity of accrued profit in relation to other actors in the Kenyan chain value). Variable parameters that would be included include those that I have described in my model. I will try to establish how the variables/attributes for various actors have been changing from 1995-2004. This will enable me to come up with a final model that will be used to determine how my dependent variable (proportion/quantity of accrued profit about other actors in the Kenyan chain value) has been changing with time from 1995-2004. My design approach will be descriptive since I will only make observations on my variables.

In order to obtain more accurate data, I will use a random sampling method to obtain data. This is because the method will minimize errors or bias that can be included while obtaining information considering that part of my samples will be considerably large. Moreover, the type of random sampling technique that I find appropriate to use will be stratified sampling to ensure that different groups in terms of various disparities that exist like sex and income levels are represented.

Target population

Targeted population in this study consists of various actors in the Kenyan maize chain value. They include the following: farmers, assemblers, dis-assemblers, small and large scale millers, wholesalers, retailers and consumers. Farmers that will be targeted in this study include both maize farmers in high production areas like Nakuru and Trans Nzoia district in Kenya as well as those in low production areas like Kitui areas. The rest of the groups will be distributed in rural areas as well as Nairobi area. While the population in Nairobi is very much easily accessible, that in rural areas is scarcely distributed and will also need the use of Kiswahili questionnaires for ease of communication. The targeted population in rural areas is however very important for our study since it includes some of the most important actors in the Kenyan maize chain value notably farmers and therefore requires to be equally represented in this study.

Targeted populations consist of different attributes that can be easily recognized for purposes of this study. For example, provided one is in the group of farmers, then it can immediately be recognized on what position is held by this individual in the maize chain value. Some of the variables in this study are null for some actors, for example, consumers are not expected to invest any capital in the maize chain value but remain as buyers. Moreover, some variables will be established indirectly after analysis of obtained data. This includes the issue of greed for example. In general, I expect the targeted population to provide me with all required information for analysis without much difficulty.

Sample design

Considering that this study is specific to profit margins accrued by various actors in the Kenyan maize chain value, this study will be conducted as a case study.

Sample size

The sample size will consist of at least three thousand actors in the targeted population.

Sampling techniques

I will use probability random sampling method to obtain my sample. This method would increase accuracy since every member of the targeted population is assumed to be represented in such a sample. The sample will be stratified to ensure that different groups are represented.

Data sources

Sources of data that will be used in this study will consist of targeted respondents. It will also include recorded information obtainable from relevant government records as well as records from other relevant parties.

Data collection

Data collection for this study is intended to establish the relationship between the dependent variable (quantity/ proportion of accrued profits) and independent variables which have been described in the model. The place where data will be collected will consist of rural areas in Kenya as well as Nairobi. The data that will be collected will consist of variables that will be used to develop the required model. For the collected data to be more accurate, use will be made of local people with a capacity of obtaining needed information efficiently. This will especially apply in rural areas to eliminate the problem of language barrier. Care will however be taken to ensure that data collectors are well trained. Use will be made of qualified personnel who will undergo short training to prepare them for the process. For actors in the maize chain value who are likely to have a busy schedule like millers and middlemen. For example, early arrangements will be made through telephone conversations to ensure that they are available for interviews. Since the data that will be collected will be considered as variable, data collectors will be trained on how to rate information obtained from respondents on a specific scale that will be used. For example, while consumers will be given the lowest scale about their position in the value chain, millers will be given the highest scale. This is to ensure that analysis of obtained data is simplified. Moreover, data collectors will be trained in a mock environment so that they can have a feel of what is expected on the ground before going out to collect data.

Data collection instruments

I will use two methods to obtain relevant data for my research. One of these methods will include an open-ended questionnaire. Unless it is in cases of exceptional circumstances, where respondents are not easily available, the questionnaire will be actively filled by researchers visiting targeted areas. Questions will be written in both English and Kiswahili for easier use by local respondents. Another technique that will be used to collect data is the use of observation techniques. This will involve securitization of relevant government records, records from the national cereals and produce board, records from previous studies similar to this among other records.

Reliability of data

Accurate methods used to collect primary data as has been described in data collection will go a long way in ensuring the accuracy of data. Secondary data obtained from recorded sources will only be derived from credible sources. Moreover, appropriate statistical techniques used to minimize errors to very low values will be employed. Besides, the fact that related research has already been carried out in this area will be used to guide this study hence a higher possibility of reliable data.

Data analysis

An SPSS computer program will be used to analyze collected data. Data analysis will include minimization of errors as well as coming up with the desired model that will show how the dependent variable of this study has been changing with time from 1995-2009.

Limitations and delimitations of study

Considering the limitations of this study, first, it will be difficult to obtain accurate information from respondents especially that touching on personal issues like income levels. With limited resources, it may also prove quite expensive to collect data especially in rural areas due to the scarce population densities that exist. Besides, the maize sub-sector in Kenya is quite complex with some unseen factors that are not easy to figure out.

On the other hand, carrying out this kind of study may be easier considering it can be guided by related research studies that have been carried out. Besides this study is supported by distinguished professionals who can willingly help at any stage. Moreover, information on some actors in the maize sub-sector chain value in Kenya is easily accessible from relevant records.

Ethical considerations

Some of the information that is needed for this study will touch on personal issues. There is therefore a need to frame the questionnaire in a non-direct way concerning these issues. The issue of maize in Kenya has lately been emotive due to increasing prices, constant shortages and exploitation of consumers.

Reference

Argwings, K. G. (1998). “Monitoring for Improved agricultural policy making,” paper presented at the conference on strategies for raising productivity in agriculture, May 12, 1998, Kenya college of insurance, Nairobi, tegemeo Institute/Egerton university. Web.

Argwings, K.G., & Jayne, T.S. (1996). Relief through development. consumer response to maize market liberalization in urban Kenya. Web.

Jayne, S. T, & Argwings, K. G. (2005). Consumer response to maize market liberalization in Kenya. Maize policy Web.

Jayne, T. S., Robert, J. M., & Nyoro, J. (1997). Effects of government maize marketing and trade policies on maize market prices in Kenya. Draft for review working. Web.

Kamau, M. W. (2002). An overview of the Kenya seed industry in a liberalized environment: A case study of maize seed. Web.

KARI (1995). Seed industry policy. Post liberalization. Web.

Kenya Plant Health Inspectorate Service. (2003). Draft Kenya national variety List. Web.

Mukumbu, M. (1994). Consumer and milling Industry responses to maize market reform in Kenya. Production and food security. Web.

Mukumbu, M., & Jayne. T.S. (1994). Urban Maize Meal Consumption Patterns. Strategies for improving food access to vulnerable groups in Kenya. Web.

Nyongesa, D.J.W, Muriithi, F.M, & Lutta, M. (2000). An economic analysis of the determinants of maize seed pricing in Kenya: A value chain approach. Kenya Agricultural research Foundation. Web.

Nyoro, K.J, Kiiru, W.M., & Jayne, S.T. (1998) Evolution of Kenya’s maize marketing systems in the post-liberalization era. Web.

Owuor, B. (2009). The troubled sector: Is our path worthwhile. Maize. Web.

Pinckney, T. C. (1999) “Is market liberalization Compatible with food Security? Food Policy. Web.

Scarborough, V. & Kydd, J. (1992). Economic analysis of agricultural markets. U.K. Natural resources institute. Web.

Scott, G. (1995) Agricultural transformation in Zambia: Past experience and Future Prospects. Food security in Africa. Web.