Abstract

With an increase in competition in the global marketplace, companies begin to seek new ways in order to gain a competitive edge over their competitors. This was the time when the organizations identified the need for adopting a new approach for supply chain management. The result was the emergence of a new concept of supply chain management, which was based on the concept of integrating the overall organizational processes, establishing communication channels at all levels of the organization and increase cooperation among all the departments which are involved in the supply chain process, whether they be external or internal. This manuscript explores the importance of both technological readiness and technological complementarity in the management of suppliers, logistics, service, quality and performance. From a resource based perspective, the results support the importance of technological readiness and technological complementarity as significant capabilities for supply chain firms in attaining superior logistics service quality. Additionally, the long standing belief that logistics service quality is a core competency that impacts superior performance is upheld. Ultimately, this manuscript gives managers insight into the dynamics of managing technology across partnerships.

Introduction

The supply process acts as the bridge between core competencies and markets. The ability to manage this process along with the strategic core is crucial to market success. There is a need to contemplate the scope of strategic thinking and action at two sections. The first is the strategic role of SCM, and the second is the benefit achieved from SCM. (Hackman, 2005, pp.309-42) In the present era of extremely competitive markets, increased level of globalization and expansion of organization’s operations to a global scale, it has become increasingly significant for the firms to fully integrate their overall operations so that they can develop a competitive edge over their competitors in terms of timely delivery, efficient customer service and improved performance. Supply chain management has been one of the major issues of concern for businesses for several years. Advancement in technology, development of innovative information systems and their successful implementation on different business enterprises has made the task of supply chain management more effective and easier to mange. While there is undoubtedly great potential in the RFID technology, there are also many implications that need to be addressed. Firstly, as already known, RFID utilizes radio frequencies to transmit its information.

The problem arises as different countries use different radio frequencies that are relatively stable and cannot be modified to suit the needs of electrical equipment. As a result, the RFID system itself has to be geared to accommodate for these different frequencies so all devices can communicate effectively. Secondly, the violation of privacy stands out again as another one of its implications. (Sitkin, 2004, pp.537-68) In this area are grouped together procurement, factory/warehouse management and logistics. These areas can all be greatly assisted by modern improvements in communications and software. A great deal of time and money is wasted by companies still relying on the use of the telephone, fax or post to communicate between these departments and with external sources. Once a company has rationalised its data storage it becomes possible to automate many inter-departmental processes. It need not stop there either, systems are available to transfer information between various trading partners; systems such as these are known as inter-organisational information systems (IOIS). The virtual corporate integration that results when such systems are adopted can lead to a reduction in what has been termed supply chain uncertainty. All companies within the IOIS will have a greater awareness of the state of play at any given time resulting in increased operational efficiency. The company that has access to this information is also going to be able to offer value added services to its customer such as order tracking. (Hackman, 2005, pp.309-42)

By implementing RFID on an international level, there is also a greater chance that privacy can also be invaded on an international level. With the aid of very sophisticated and powerful tag readers, people can access the information of others from several feet away. And depending on the data stored on the tags, it can potentially be disastrous to its owner, who is completely unaware that he or she has been scanned. The RFID tags contain various metallic substances that are very difficult to recycle. This poses a potential cost processing obstacle as the WEEE (Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment) regulation disallows this kind of material from being discarded like garbage. As a result, the material used in the creation of RFID tags may have to be modified in order to ease the recycling process. With all the advantages of this technology, why has it not become popular in the economy yet? RFID tags are used in many industries currently; however, they are not used to the extent of their optimal capabilities.

There are a few reasons behind this, including costs, internal inconsistent technology, as well as ROI, which is not always so apparent. The implementation of RFID remains fairly expensive as discussed earlier. In applications such as supermarkets moving to a fully integrated RFID system, it is often seen as being far too pricy relative to the existing bar coding system. Within the industry itself, the manufactures of these RFID tags have yet to establish a standardized system. The industry needs to focus on a team effort between integrators, end users, and manufacturers in order to have producers buy into the technology. Although there have been many business proposals regarding RFID, most management teams are too focused on short-term goals to realize the full benefits of using RFID. Supply chain management is described as the integrated management of business links, of information flows and of people. Attention is given to the whole chain from raw material supply, manufacture, assembly and distribution to the end customer. For manufacturers, operations are the heart of the supply process, and supply is not the sole criterion of competitive advantage, but it performs a crucial role in support of other strategies. Investments and longer-term developments in manufacturing are examined in relation to changes in business strategy.

The second major trend facing organizations is the demand for ever-greater levels of responsiveness and shorter defined cycle times for deliveries of high-quality goods and services. All functions have a part to play in the development of strategy and manufacturing should be involved as well. Manufacturing is seen as a strategic resource and development of capabilities is important. This may open new market opportunities. As a result, in manufacturing companies, SCM seeks to play one of two distinct roles:

- To establish competitive advantage through unique logistic performance

- To achieve higher efficiency through cost leadership

Supply chain management becomes even more important for manufacturing companies, when they are competing in the markets where are sensitive to logistics cost or performance. And the management must balance supply chain effectiveness (the quality of the products) against efficiency (low cost). Another important trend in supply chain management is the recovery, recycling, or reuse of products from the end user after they have reached the end of their useful life. Organizations are now extending their distribution channels beyond the end customer to include the acceptance and ‘disassembly’ of final products for reuse in new products. (Eskigun, et.al, 2005, pp.182-206)

Purpose of the study

In this paper we will go through today’s modern technologies such as RFID been frequently used in supply chain management. After studying two case studies one on Unilever and another one on English biscuits, in which we will analyze how these two organizations uses the technology in their supply chain management system. In section two we will discuss theories of supply chain and what already has been written on the subject. After doing that we will turn towards the methodology chapter in which we will explain the method of collecting data, and than showing the result and analysis of the findings. However, it is significant to note that these newly developed information systems just functions as the facilitators in managing the supply chain management activities and it is still the responsibility of the management of any given organizations to plan and manage the overall supply chain and inventory management activities. The impact of the challenge posed by supply chain management issues can be huge on the firms, especially for the retailing organizations. For retailers as well as the manufacturers, supply chain management can serve as one of the most significant areas of differentiation. It can help the organization to gain an edge over its competitors if they manage their supply chain management systems well.

On the other hand, if the organization fails to realize the importance of supply chain and ignores this crucial aspect of business, it can prove to be a considerable burden for the organization. Realizing the importance of supply chain, in enabling an organization to successfully compete in the market, researchers and management experts have been working out to identify strategies and practices which may enable the companies to improve its capabilities in terms of matching supply and demand for its products. It is also interesting to note that in case of retail businesses, effective supply chain management has become an essential aspect of business as the life cycles of the majority of the products have shortened because of an increase in competition. With a rise in competition among the organizations, one can observe an increase in the breadth of product offerings in the market, which leads to a shorter product life cycle. With the introduction of a new product in the market, the life cycle of some other products, offered in the same product category, tends to reduce. It has therefore become essential for the retail firms to effectively manage their supply chains so that they can efficiently manage the supply and demand aspects of a certain products according to its changing life cycle stages. It requires a clearly defined and reliable forecast, with respect to the future demands of products. It should however be noted that presently the majority of the forecasting techniques and tools employed by retailing firms are focused towards products having long life cycles.

Objectives

In the world of advancement and global village, gradually it is becoming nearly impossible to not pursue certain technologies particularly in the field of supply chain management that enables you to drive the business in a flourishing way. As mentioned above the objective of this paper will be demonstrating the significance of RFID in the field of supply chain management. We will glance through the lenses of two companies the one is Unilever and another one is united biscuits, what impact they had when they switch over their traditional supply system into modern RFID system. Through questions we will examine the significance and changes these organizations demonstrate today.

Supply chain and RFID?

RFID is a system that uses an electronic product code, or EPC, or similar numbering scheme that relies on the storage and retrieval of data using devices called RFID tags or transponders. An RFID tag can be connected to a product, animal, or person to recognize or follow that object by radio waves. The tag reader may be able to pull data that identifies the object’s location; reports specifics about the product, such as the date of purchase, colour, or size; or relates the price. The first notable application of RFID was in 1939 by the British. The application, called IFF for “identify friend or foe,” was a transponder routinely used by the Allies during WWII to identify friendly or enemy aircraft. IFF transponders are still used by military and commercial aircraft today. (Deschner et. all 2000 283-92)

In a typical commercial system, a tag is attached to an object. These tags contain a transponder with a digital memory chip that carries a unique electronic product code. A signal emitted from a device called an interrogator activates the RFID tag so data can be read from or written to the tag. When the tag goes through an electromagnetic region, it finds the opening signal emitted from the reader. The reader then decodes the data on the tag, and the data is transmitted to a host computer. Specific application software contained on the host computer then processes and sorts the data into prescribed reporting and storage formats for the end users. There are three types of RFID tags: passive, semi-passive, and active. Passive and active tags will be discussed in this article. Passive RFID tags, which are silicon-based, have no internal power supply. There is, however, enough electrical current generated by the antenna via the incoming radio frequency signal to transmit a response back to the interrogator. Since the passive tags have no internal power supply, they are very small. There are tags commercially available that can be imbedded under the skin.

Today, the smallest passive RFID tags measure 0.15 mm x 0.11S mm and are thinner than a sheet of paper, which is approximately 7.5 micrometers. The cheapest tags, typically purchased by mass merchandisers such as Wal-Mart and Target, cost $0.05 each, and have a read range of between 4 inches to a few feet, depending on the radio frequency and antenna design and size. (Bond, et. all 2000 17-26) Several companies, including Philips of The Netherlands and PolyIC of Germany, are working to produce non-silicon-based tags from polymer semiconductors. This will let the tags to be “roll printable,” similar to a magazine, and consequently will be a great deal less expensive to manufacture. Over the next few decades, experts expect these RFID tags to be printed like barcodes are today, and are virtually free to produce. (Anand, 1997, pp.1609-1627) An early benefit of supply chain improvement efforts included project work by teams that reduced purchasing costs, inventories, logistical costs, and freight costs. As the focus is placed on specific supply chain projects such as mainly clerical, order-pacing activities and in which personnel tend to adopt only a short-term, hand-to-mouth approach, merely reacting to contingencies as they arise.

Supply chain objectives are usually described by two opposing goals: satisfying customers (effectiveness) and achieving the highest possible efficiency, and the way in which balance is achieved is the fundamental benefit of supply chain strategy. Supply chain effectiveness indicates how well it is oriented to the customer. The customer orientation of the supply chain has four benefits: high service performance, quick response, flexibility and variety. The benefit of SCM for manufacturers is the quick change in supply chain and introduces new products to meet the turbulent conditions of the market. Inventory becomes obsolete. In the long run, there seems to be general support for the view that in rapid changing world markets, product innovation is an essential ingredient in the capability of firms to sustain a competitive advantage. Linkage with suppliers and the relationships that are forged with them can help to stimulate technological changes that can benefit both parties. The alternative is to emphasize flexibility and time-based cycle. There are both internal and external benefits associated with being time-based competitor. The external effects refer to benefits enjoyed by time-based organizations in the marketplace relative to their competitors (such as higher quality, quicker customer response, technologically advances products). The internal benefits are found within and between the different functional areas in the firm including simplified organizations, shorter planning loops, increased responsiveness, better communication, coordination and cooperation between functions. (Hackman, 2005, pp.309-42)

Active tags have their own battery-operated internal power source. They are much more reliable than passive tags, transmitting signals to the reader at a higher power level and having ranges of up to 300 feet. These batteries can last tip to 10 years. (Ellram, 2006, pp.13-22) In addition, because their power source is stronger, they are reliable when imbedded in products containing mostly water, such as human’s and cattle, and metal, such as containers and vehicles. More sophisticated versions of active tags could include sensors that measure temperature, humidity, shock and vibration, light, and radiation. Whereas the passive tags are approximately $0.05 each and 0.15 mm in length, active tags are about the size of a comb and cost a few dollars each, significantly more expensive than their passive counterpart. (Edgeman, 2005, pp.75-79)

Traditional strategies for supply chain management

Establish supplier relationships

It is important to establish strategic partnerships with suppliers for a successful supply chain. Corporations have started to limit the number of suppliers they do business with by implementing vendor review programs. These programs strive to find suppliers with operational excellence so the customer can determine which supplier is serving it better. The ability to have a closer customer/supplier relationship is very important because these suppliers are easier to work with. With the evolution toward a sole supplier relationship, firms need full disclosure of information such as financial performance, gain-sharing strategies, and plans for jointly designed work. They may establish a comparable culture and also implement compatible forecasting and information technology systems. This is because their suppliers must be able to link electronically into the customer’s system to obtain shipping details, production schedules and any other needed information. (Edgeman, 2005, pp.75-79)

Manage inventory investment in the chain

Each constituent of the supply chain desires to hold no more than its fair share of inventory. For instance, the distributor desires fewer inventories and would like to see inventory held by the manufacturer. As a result, the concept of vendor-managed inventory has become a trend in inventory management. This system allows the inventory to be pushed back to the vendor and as a result lowers the investment and risk for the other chain members. As product life cycles are shortening, lower inventory investment in the chain has become important. Cycle times are being reduced as a result of the quick response inventory system. The quick response system improves customer service because the customer gets the right amount of product, when and where it is needed. Quick response also serves to increase manufacturing inventory turns.

Build a competitive advantage for the channel

Achieving and maintaining competitive advantage in an industry is not an easy undertaking for a firm. Many competitive pressures force a firm to remain efficient. Supply chain management is seen by some as a competitive advantage for firms that employ the resources to implement the process. It also serves to increase the clout in the channel because these firms are recognized as leading edge and are treated with respect. Attaining competitive advantage in the channel comes with top management support for decreased costs, waste management, and enhanced profits. Many firms want to push costs back to their supplier and take labour costs out of the system. These cost reducing tactics tend to increase the competitive efficiency of the entire supply chain. Firms have become more market channel focused. They are observing how the entire channel’s activities affect the system operation. In recent times, the channel power has shifted to the retailer. Retailer channel power in the distribution channel is driven by the shift to some large retail firms, such as Wal-Mart, Kmart, and Target. The large size of these retailers allows them the power to dictate exactly how they want their suppliers to do business with them. The use of point of sales data and increased efficiency of distribution also has been instrumental in improving channel power and competitive advantage. (Sitkin, 2004, pp.537-68)

Increase customer responsiveness

To remain competitive, firms focus on improved supply chain efforts to enhance customer service through increased frequency of reliable product deliveries, increasing demands on customer service levels is driving partnerships between customers and suppliers. The ability to serve their customers with higher levels of quality service, including speedier delivery of products, is vital to partnering efforts. Having a successful relationship with a supplier results in trust and the ability to be customer driven, customer intimate and customer focused.

5. Information is vital to effectively operating the supply chain. The communication capability of an enterprise is enhanced by an information technology system. However, information system compatibility among trading partners can limit the capability to exchange information. An improved information technology system that is user friendly, where partners in the channel have access to common databases that are updated in real-time, is needed. (Edgeman, 2005, pp.75-79)

Background

Supply chain management as a concept has been evolved to address a number of issues that effect modern companies as follows. The number of suppliers that companies use has tended to increase greatly, for example Sun Microsystems has three factories of its own but uses its supply base to increase its productivity by a factor of a hundred. (Ellram, 2006, pp.13-22) Sourcing from such a large supplier base allows a company to choose the best value components available from the world market giving added value to the customer; the downside is the obvious extra management burden that comes as a result. Economic factors such as global recessions and increased global competition have forced companies to focus not just on their product but also on streamlining every process across the value chain from the component suppliers to the end vendor. As supply chains grow in size and complexity it can become apparent that there are dependencies between companies in the supply chain. For instance a smaller size supplier may maintain a line purely to service a larger company. When this happens it makes sense to share information between the companies and maybe even to go as far as integrating systems for mutual benefit.

In the 1970s procurement professionals played a key role in cutting costs to help companies compete during the energy crisis, in the 1980s procurement had to again find ways to cut costs to fight against the competitive advantage of high quality and low priced Japanese products. From the mid 1990s to present, procurement professionals are combining best practices with technology to streamline processes, control costs, achieve operational efficiency and deploy strategic procurement initiatives across the enterprise. (Kanji, 1998, pp. 633-48)

As can be seen from the above statistic there is huge scope for clawing back lost potential revenue in this area. If, for example, at the end of a supply chain, company A is supplying vendor B; it is quite possible that both companies might keep a reserve surplus stock or worse still, they may both run out of stock. The solution here, as I hinted at earlier, is to share information between the companies or even to integrate systems. This has been implemented in a number of different ways; we shall examine VMI (Vendor Managed Inventory) and CRP (Continuous Replenishment Program). With VMI: Company A is able to access B’s inventory records and when they fall below a level, set by B, send more stock and raise the appropriate purchase orders. With CRP: Data from the whole of the supply chain is analysed with the goal being that when an item is purchased from the vendor (B) a message travels back through the supply chain requesting the production of a new replacement item.

So far this would seem to be similar in effect with VMI; CRP however, makes use of the extra data it has, to make a prediction of the likely sales on a given day and sets the recommended level of stock. This is known as demand forecasting. Depending on the complexity of the implementation CRP may be able to take into account general trends, seasonal trends or other known patterns specific to a given product. One of the basic tenets of supply chain management practices is that a company opens up its computational resources and business processes to its customers and trading partners. These partners will use these computer networks to gather information, place and receive orders, initiate and manage payment cycles, and handle fulfilment. In opening up their computational systems to trading partners, however, companies magnify the chance of unwanted intrusions into their networks. In addition, a wider range of employees now has access to these computational networks than when traditional, paper-based processes were prevalent.

There are numerous current and planned uses of RFID technology. RFID tags are currently being imbedded in passports, enabling the recording of travel history, including time, date, and place of entry and exit from a country. Exact figures on the use of RFID technology in approximately 13 million new U.S. passports are unknown, but the technology was introduced in the U.S. in 2006. In the transportation industry, the use of RFID technology is widespread and growing. Common uses of RFID tags in East Coast transportation include the EZ Pass, FasTrak, I-Pass, Pikepass, Fast Lane, and SunPass systems, among others. Many metropolitan transportation systems are using or testing new and improved RFID methods, including the New York City subway, the Moscow Metro – the first system in Europe to introduce RFID smartcards in 1998 – as well as the London, Taipei, Paris, and Hong Kong transportation systems, among others. In addition, transportation distribution centres are increasingly using RFID to track trailers and trucks to ensure specific trucks are hauling the correct trailer to a desired location. (Melchiors, 1998, pp.111-22)

In product tracking, RFID technology is growing, and includes the tracking of manufactured inventory, books from libraries and bookstores, building access, and airline baggage. The automotive industry recently started using RFID in car keys as theft protection. Toyota is implementing a Smart Key/Smart Start system, whereby car doors can be opened and the car can be started using a wireless and keyless system of entry, as long as the key’s presence is registered via RFID within 3 tact of the sensor. Prison systems in Michigan, California, and Illinois have RFID-based tracking systems that enable the movements of prisoners to be tracked via the use of wrist-watch-sized transmitters. If inmates try to remove the transmitters, the prison’s computer system alerts prison guards. Mass sporting events – such as marathon races, triathlons, and the like – provide for the tracking of the competitors’ progress throughout the race using RFID chips embedded in the identification numbers worn on the racers’ shirts or shorts.

Sometimes, RFID use is mandatory, as stipulated by government or industry regulators. For example, the FDA recently announced new anti-counterfeiting guidelines for life sciences firms, including a requirement for attaching RFID tags with EPC codes to all primary items in the supply chain. Also, the Transportation Safety Administration has several initiatives under way, including the Container Security Initiative (CSI) and Operation Safe Commerce, and the U.S. Department of Defence is in the process of requiring all of its suppliers to adopt RFID. These initiatives are designed to identify high-risk containers and enhance import security on commercial shipments entering U.S. ports from foreign sources. The use of RFID tags is one part of the overall container security plan a firm may employ in the process of adhering to the CSI. The RFID industry is expanding substantially. Per the IDC, companies in all industries spent $92 million on RFID in 2003. This spending level is expected to increase to $1.3 billion by 2008. If these projections hold true, RFID technology will be here to stay. (Daskin et all 2002 83-106)

Literature Review

In recent years, several studies (Forker et al., 1997; Tan et al., 1998, 1999; Choi & Rungtusanatham, 1999; Kanji & Wong, 1999; Romano & Vinelli, 2001 1681-1701) have addressed quality as a key strategic variable that should be considered and managed not only within the single firm, but also across the supply chain of which the firm is part. In fact, the quality level delivered to the final customer is the result of quality management practices of each link in the supply chain, thus, each actor is responsible for the final result. This has meant a shift in the managerial approach to quality, from a perspective focused on the single firm and its internal quality system, to a broader view that also considers customers and suppliers or, in other words, the supply chain in which the firm operates. Beamon & Ware (1998 281-94) maintain that improving the quality of all supply chain processes leads to cost reductions, precise resource utilization, high process efficiency, and eventually superior quality levels incorporated in products delivered to final consumers. Capabilities of core inter-organizational processes, such as customer relationship management, supply chain management, and contract manufacturing, are suggested as critical to firm performance (Hagel and Singer 1999; Rayport and Sviokla 1995; Sambamurthy et al. 2003).

Their digitization across the extended enterprise is being enabled by Web technologies, workflow tools, and portals for customers, suppliers, and employees, and information technology innovations targeted at supply chains and customer relationships. Firms are investing in these technologies and related partnerships to develop their extended enterprise capabilities. Supply chain management (SCM) is a digitally enabled inters firm process capability that has been receiving significant attention. Practitioner forums such as the Supply Chain Management Council have been established and special issues of Decision Sciences and Journal of Operations Management have been recently published on the topic. However, in spite of the key role of RFID in the SCM phenomenon, thus far limited scholarly investigation has been undertaken by the Information Systems community. Our objective is to present a theoretical viewpoint, supported by empirical evidence, on how RFID enables supply chain integration capability to yield performance gains for firms. Supply chain strategies focus on improvement and innovation of end-to-end processes between firms and their customers and suppliers (Lee 2000; Tyndall et al. 1998). Case studies document problems caused by supply chain fragmentation across different industries and best practice reports profile the potential of RFID to address them (Enslow 2000; Rai and Sambamurthy 2002; Simchi-Levi et al. 2000).

These descriptions suggest that supply chain integration (1) requires partners to share information and develop globally optimal plans (Ho et al. 2002; Simchi-Levi et al. 2000), (2) optimizes the staging and flow of materials by leveraging the visibility of resources (Lee 2000), and (3) streamlines financial operations such as billing and payments that are interdependent on other activities such as ordering and delivery (Mabert and Venkatraman 1998). In summary, supply chain integration encompasses the integration of information flows, physical flows, and financial flows between a firm and its supply chain partners. Supply chain integration can be hampered by fragmented RFID infrastructures that constrain information flows and activity coordination (Barua et al. 2004; Sambamurthy et al. 2003). In contrast, integrated RFID infrastructures that are characterized by common data standards and integrated applications enable flows of information and coordination of activities across functional units, geographic regions, and value network partners (Broadbent et al. 1999). As illustrated below, such integrated RFID infrastructures for SCM are being exploited by best-practice firms for superior performance. Traditionally, SCM issues have been investigated by operations management researchers with a focus on functional problems, such as facilities location and transportation (Geoffrion and Powers 1995), inventory management (Cohen and Lee 1998; Mabert and Venkatraman 1998), materials management, purchasing, and distribution (Scott and Westbrook 1991; Turner 1993).

Similarly, RFID impacts in the context of SCM have been mostly investigated with a focus on specific technologies and innovations, such as EDI (Srinivasan and Kekre 1994), cellular manufacturing (Black 1991), and vendor-managed inventory (Ellinger et al. 1999). Recent recommendations encourage researchers to focus investigations on the inter-organizational capabilities that integrate a firm with its network of suppliers and customers to create value for firms (Ho et al. 2002; Narsimhan and Jayram 1998). Extending on the resource-based view of the firm (Barney 1991), higher-order organizational capabilities are suggested as a source of firm performance in the strategic management literature (Grant 1996; Teece et al. 1997) and, more recently, in the IS literature (Barua et al. 2004; Mithas et al. 2004; Sambamurthy et al. 2003). According to this perspective, a firm must develop capabilities to acquire, integrate, reconfigure, and release resources that are embedded in their social, structural, and cultural context. Developing these capabilities is a long-term process that requires firms to make a series of linked strategic decisions and moves related to RFID resources so as to blend them with organizational processes and knowledge resources (Barua et al. 2004).

Viewed from the perspective of organizational capabilities and resource-based theory, commonly available RFID resources cannot by themselves create sustained performance gains for a firm (Floyd and Wooldridge 1990; Powell and Dent- Micallef 1997; Zahra and Covin 1993). Accordingly, conceptual distinctions have been made between RFID components broadly available in the marketplace, integrated RFID platforms that require significant time and expertise for development (Weill and Broadbent 1998), and RFID-enabled processes that deeply embed capabilities of RFID platforms into organizational processes (Bharadwaj 2000). A well-integrated RFID platform is much more than individual physical components. RFID requires standards for the integration of data, applications, and processes to be negotiated and implemented in order for real-time connectivity between distributed applications to be achieved (Ross 2003; Weill and Broadbent 1998). From our perspective, an integrated RFID infrastructure enables consistent and real-time transfer of information between SCM-related applications and functions that are distributed across partners. Such integrated RFID infrastructures for SCM can be blended with inter-organizational processes to develop higher-order capabilities for demand sensing, operations and workflow coordination, and global optimization of resources.

These capabilities require firms to unbundle the three complementary flows of materials (Stevens 1990), information (Lee et al. 1997), and finances (Mabert and Venkatraman 1998), and integrate each of them with supply chain partners. Accordingly, we consider information, physical, and financial flows in our framing of a focal firm’s supply chain integration capability. The literature identifies important flows across the supply chain to include materials (Stevens 1990), information (Lee et al. 1997), and finances (Mabert and Venkatraman 1998). Accordingly, supply chain process integration is defined as the degree to which a focal firm has integrated the flow of information, materials, and finances with its supply chain partners. Although knowledge flows are discussed in the literature (Carlile 2002), they are sometimes overlapped in their definition to include information flows, and we do not consider them as a distinct flow in our investigation. Accordingly, supply chain process integration is conceptualized as a formative construct with three sub-constructs: information flow integration, physical flow integration, and financial flow integration. Information flow integration is defined as the extent to which operational, tactical, and strategic information are shared between a focal firm and its supply chain partners. Specifically, we consider the sharing of demand-related information, inventory and sales positions, production and delivery schedules, and performance metrics as indicators of information flow integration. Seidmann and Sundarajan (1997) note that operational information sharing can leverage the economies of scale and expertise across organizations, inventory holding information, when shared, can reduce total inventory in the supply chain (Lee et al. 1997).

Similarly, production and delivery schedules can be shared to enhance operational efficiencies through improved coordination of allocated resources, activities, and roles across the supply chain (Lee et al. 2000). Tactical information sharing can encompass performance metrics associated with execution of tasks and their outcomes. Finally, strategic information sharing occurs when the information possessed by a firm generates little value by itself, but creates strategic value when shared (Seidmann and Sundarajan 1997). For instance, sharing of sales information by buyers with sellers creates value through improved demand planning, forecasting, and replenishment. RFID has been shown that lack of sharing of actual sales information substantially distorts the demand signal as RFID travels upstream across the supply chain. The phenomenon of upstream amplification of error in the demand signal is called the bullwhip effect4 (Lee et al. 1997) and causes problems such as excessive or inadequate inventory, poor production and capacity planning, cash flow utilization, and customer service. Information sharing allows retailers, manufacturers, and suppliers to improve forecasts, synchronize production and delivery, coordinate inventory-related decisions, and develop a shared understanding of performance bottlenecks (Lee and Whang 1998; Simchi-Levi et al. 2000).

By substituting information for inventory holdings (Milgrom and Roberts 1988), information flow integration can improve operational performance by reducing inventory costs, enhancing capital and cash flow utilization, and improving cycle times. By improving the precision of demand estimation through collaborative forecasting, and facilitating supply and demand alignment, information sharing can strengthen bonds with customers and generate increased revenues from existing products and new products and markets (Anderson et al. 1994; Mohr and Nevin 1990). Past framings of RFID infrastructure identify reach and range as important business functionalities enabled by RFID infrastructure platforms (Broadbent et al. 1999; Keen 1991). Reach refers to the connectivity of the RFID infrastructure, while range refers to the variety of information resources that can be exchanged by the RFID infrastructure. In the context of SCM, cross functional applications integration enables near real-time connectivity across a range of complementary applications focused on planning and execution, and their connectivity with applications for enterprise resource planning and customer relationship management. Having common data definitions and data consistency not only enables connectivity across the supply chain, but also enables the exchange of complementary information between a firm and its supply chain partners.

Gap between literature and reality

Drawing on the resource-based view of the firm, Bharadwaj (2000) expanded our conceptualization of RFID-based resources to include RFID infrastructure, human RFID resources, and IT enabled intangible processes. She notes the limitations to conceptualizing RFID infrastructure as a lower-level tangible physical resource, which, by definition, is more likely to be mimicked by competition. Instead, an integrated RFID infrastructure represents a capability that is not easily mimicked as RFID is established through a combination of lower-level tangible resources and complementary intangible and human RFID resources. Our results provide evidence that RFID infrastructure integration targeted at SCM enables the transformation of fragmented, functional, silo-oriented supply chain processes to integrated, cross-functional, inter firm supply chain processes. The latter are characterized by synergies derived from integrating resource flows between a firm and its supply chain partners. An inspection of the weights associated with the two formative indicators (i.e., data consistency and cross-functional SCM application integration) suggests that both are critical elements of RFID infrastructure integration in this context.

However, data consistency is relatively more important, in comparison to cross-functional application integration, suggesting the high degree of importance of data quality and standards as facilitators of process integration. Certain technology areas such as container security, the use of REID tags, and container screening have become more established, with coalescing standards and multiple vendors, and a history of user experiences. Firms can draw on this history to assess competing technologies and make decisions about deployment. In other areas, technology solutions may be in an emergent phase, performance will improve and uniform standards are likely to emerge, and preserving technological flexibility will allow firms to take advantage of emerging developments and implement desirable technology upgrades. Firms can participate as lead users to help influence technology direction and improvement, functionality, and standards. Since information gathering and sharing is a central part of security measures, inter-operability is critical, and industry bodies such as EPC global have been setting and improving standards (for REID and electronic product tags). The firm’s role is to ensure that standards are commercially viable, and that these technologies work well with complementary resources such as software and other installed hardware. Technology- based solutions are not the only way to enhance security, nor are they fool-proof, and they should be complemented with overall supply chain redesign and with collaboration across the supply chain and with industry, governments, and multilateral organizations.

Benefits and Cost from Supply Chain Security

Supply chain security systems are costly, with upfront investments and ongoing operating costs. At a minimum, systems such as container security or RFID tags will include the costs of system installation, monitoring, responding to system alerts and information, and maintenance. Other lifecycle costs could include technology upgrades, software development, database maintenance, and smart container retrieval. DHS launched the Operation Safe Commerce program, in partnership with commercial users, to test security options and develop information on the costs and benefits of operating such systems. This gives users a voice in setting standards and testing prototypes, and allows them to weigh in on alternative approaches and solutions and their cost implications. Containership charter rates have been on the rise, so the added cost of security related activities affects competitiveness. CTPAT membership and discussions allow members to influence security mandates and procedures so as to balance costs and benefits. The principal intent of supply chain security innovation is to avoid and minimize disruptions, which, if achieved, would be the overarching benefit. Such investments can have corollary and simultaneously positive impacts in lowering total supply chain system cost, through greater in-transit visibility of cycle time and material flow, and timely and accurate shipment data and transportation status.

Better, accurate, and timely supply chain information allows for managing the supply chain with lower buffer stock and pipeline inventories, with greater confidence about supply chain performance. Supply chain operators can detect where the delays are occurring so that the supply chain can be improved and made more efficient. The increased visibility of containers, their location and progress through the supply chain, and detailed knowledge of container contents and expected arrival allows for savings in inventory levels, reduced lead time variance, increased manufacturing uptime, reduced out-of-stocks, reduced theft, and better service to the importer, as well as better relations with customers and suppliers (Bhatnagar and Viswanathan 2000; A T Kearney 2004, 9; Sheffi 2001; Sheffi and Rice 2005). Supply-chain-focused security initiatives can also yield market benefits. For example, RFID tags can continuously monitor demand and thus allow the firm to adjust production quantities, order components, and route finished goods to end-user markets with the greatest unfulfilled demand. This can enhance customer satisfaction, result in repeat business and customer retention, and ultimately enhance overall profitability. Additionally, integration of supply chain information with the broader manufacturing operations and marketing databases can help automate customer receipt of goods and promote faster payment of receivables, lowering working capital needs.

Table 2 summarizes the costs and benefits of security oriented supply chain enhancements, considering their impact on both supply chain efficiency and effectiveness. Some security costs are likely to be unavoidable. Governments may mandate threshold levels of cargo security, and governmental agencies in charge of security, such as DHS, might promulgate new fees to pay for security costs. Regulations from entities such as CBP could increase the adoption of container sealing and motivate increased participation in CSI and C-TPAT initiatives. For example, passive container seals could become mandatory on all maritime containers. Passive tags would be relatively inexpensive, costing about $0.40 to $0.50 each, while the active tag system might cost $70 to $100 per unit, depending on features such as memory, communication capabilities, ability to read and receive and transmit data from different sources and sensors, and multi-band and multi-standard transmission. When containers are selected for physical screening or universal screening as proposed by the port of Hong Kong, there are costs of unloading and inspection of these selected containers. Damage to containers from such screening is another expense that might burden carriers and importers.

Moreover, containers with security problems might go unclaimed, leading to fines and disputes over responsibility for such fees: Would the onus be on the exporter, shipper, or importer? Keeping in the mind the example of the airline industry, where much of the incremental security costs have been passed on to the consumer in the form of ticket price surcharges, RFID is likely that supply chain security costs would be charged eventually as user fees or built into port tariffs. Many importers rely on third-party logistics providers (3PLs). In such a framework, 3PLs would be expected to provide the security solution, and perhaps bear liability. If supply chain activities are outsourced through 3PLs, security- related costs are likely to be passed on to the 3PL’s clients, through a transaction pricing or a subscription model. Even if the (importer) firm is managing its logistics, and purchasing services directly from shippers, RFID might still choose to buy security-related services as a stand-alone service from security specialists. Thus, the supply chain network might further specialize, with the emergent new role of security specialist firms, and the consequent evolution of supply chain integrators who can work to include such security specialists in the overall supply chain management.

The U.S. Army has been a major proponent of using RFID tags to “provide a common, integrated structure for logistics identification smart containers, and tracking, locating, and monitoring of commodities and assets throughout the Defense Department.” The Defense Department issued a Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), which mandated the use of passive RFID tags on certain classes of defense procurement such as operational rations, clothing, individual equipment, tools, and weapon system repair parts (GCN 2005). In the private sector, Wal-Mart has been an early mover in requiring a growing number of its suppliers to equip their product shipments to Wal-Mart with RFID tags. Acer uses RFID to monitor and efficiently operate both incoming supplies into Taiwan and China and then the reverse flow of final products to international markets. Levi Strauss has used RFID in item-level tagging, giving them more precise information about on-shelf availability of their vast assortment of clothing and accessories, by details such as size, style, and color. Pfizer has used RFID to fight counterfeiting of drugs such as Viagra, while San Francisco Airport has used RFID to track baggage during handling. (Edgeman, 2005, pp.75-79)

The RFID tag stores data, and when attached to a sealed container and activated, wirelessly communicates on a given radio frequency with the logistics network. Active tags allow constant updating of information, such as where the container stopped, who had access to RFID, and whether contents had changed. Active tags can process information relayed by sensors that detect changes in pressure, radiation, chemical signatures, etc. This continuously updated information can be constantly communicated en route. At the container’s final destination, the tag can be completely read, the data analyzed and archived, and the tag deactivated and ready for re-use if possible (A T Kearney 2004, 7). The RFID tag data provide an audit trail of the container’s journey, and help keep track of its location and contents, meeting the needs of supply chain efficiency and security (Tirschwell 2005c; Wall Street Journal 2005a; Edmonson 2004). Since active RFID tags can be reused and rewritten, they have to be protected against unauthorized intrusion and hacking (Weis 2003; Juels 2005). Reusable active tags cost more than passive tags. An active tag system would require larger investments to support repeated use over the multi-year container life (Molar 2004).

A Defense Department study derived an estimate of $70 to $100 per reusable tag (Department of Defense 2005, 18), though, as early adopters, they paid premium prices. The costs of reusable tags are likely to come down with growing volumes of use. Nonetheless, equipping all of a shipping company’s containers with active tags and related communication infrastructure could be an expensive investment. The relevant cost is the total system cost of antennas, readers, tags, software, installation, service, and maintenance. RFID usage and efficiency is affected by a number of factors: cost and read reliability of the tags, the range from which tags can be read, the speed with which tags can be read, tag durability, the ability of tags to store and provide rich information, and the extent to which tag usage can be relatively free of the need for human intervention. RFID tags can vary in their performance dimensions, as not all users have the same need for rich data, longer range, and higher-speed communication. RFID readers also vary in their capabilities, with some readers better able to perform in high noise situations, with greater range, better security features, and lower error rates. RFID solutions also vary in their ability to interface with enterprise databases and software. RFID has several advantages over barcodes: no line of sight is required as in reading barcodes, the tags can withstand harsh conditions, as in ocean travel, and multiple products can be scanned at once.

RFID Standards Development in literature

The development of RFID standards provides insight into the role that industry efforts can play in developing standards that can help supply chain security, as opposed to accepting government derived and -mandated standards. The current second generation standard, EPC Gen 2 Electronic Product Code, was originally developed by the Auto-ID Center to complement barcodes, and provide information to help identify manufacturer, product category, and the individual item. Auto-ID Center is a non-profit collaboration between private companies and academia that pioneered the development of an Internet-like infrastructure for tracking goods globally through the use of RFID tags carrying Electronic Product Codes. The Gen 2 standard uses a single UHF specification, allows different communication speeds depending on background noise, is better at reading distant tags at the edge of the reader’s range, improves the operations of multiple readers in close proximity, and allows tags to communicate with multiple readers in parallel sessions.

In September 2003, the Auto-ID Center passed on its work to university-based Auto- ID Labs, located principally at MIT. Another organization, EPC global, was created to diffuse and expand the standards being developed. EPC global is a non-profit organization jointly set up by the Uniform Code Council (the organization that oversees the UPC barcode standard) and EAN International (the barcode standards body in Europe) to develop global standards for RFID use, to promote EPC technology, and to stimulate global adoption of the EPC global Network, which facilitates the seamless use of EPC and RFID across global supply chains. RFID tag fraud. The expanding use of RFID and its growing role in safeguarding supply chain security means that the system must be able to guard against RFID tag fraud. For example, the Exxon Speed Pass has an embedded an RFID tag with user information so that a motorist can wave a Speed Pass at the gas pump and have payment charged to the account of the person whose information is stored on the Speed Pass. If this information could be altered or copied, billing errors could occur and the wrong account could be charged. Juels (2005) has shown how an encryption code in Exxon’s Speed Pass could be uncovered, allowing fraudulent alteration.

This problem is more significant in reusable and read-write tags. EPC Gen 2 standards have attempted to prevent such fraudulent alteration by embedding lock codes; if the RFID reader tries to keep feeding different lock codes, in order to enable the rewrite capability, the tags could be deactivated for a certain period. Weis (2003) outlines several security proposals to combat such security weaknesses, such as limiting access to RFID tags through hash locks (a hash being a value computed from a randomly selected cryptographic key), and the use of low-cost hash functions such as cellular automata-based hashes. Weis also outlines proposals to prevent eavesdropping on a tag’s content when broadcast to the reader. Longer lock codes and encryption can help guard against such “hacks.” If attempts are made to change the product identification, that is, it’s EPC, software could check to see if a duplicate EPC exists anywhere in the world (though this assumes real-time access to a global EPC database and complete interoperability). Beyond security applications, RFID has immense value for supply chain management in tracking quantities and the movement of goods across geographically distant points in the supply chain network. ‘ ‘RFID provides incredible transparency and clarity in the supply chain,” noted Robert Turk, who serves as national director for supply chain at Siemens and played a central role in Siemens’ RFID efforts. Thus, the costs of an RFID system installation can be balanced against the benefits from greater supply chain efficiency and effectiveness, as well as impacts such as lower pipeline and buffer stock inventories and greater customer satisfaction from receiving accurate shipment information and on-time delivery of orders. (Edgeman, 2005, pp.75-79)

Prospective uses of RFID in Supply chain management

As the technology advances, the potential uses and acceptance of RFID will grow steadily. Some potential uses of RFID technology include tagging poultry in order to track their movements, which can enhance worldwide efforts in controlling a future bird flu epidemic; implanting RFID tags in humans, incorporating personal medical information on the tags thereby potentially saving lives and limiting injuries from errors in medical treatments; and using RFID tags on all food stored in a refrigerator that will be equipped to read the tags and notify the homeowner of pending expiration dates. In terms of a learning curve, as mentioned above, RFID is still very much at the beginning of its potential for exploration and use. While the technology has seen some momentum, widespread industry implementation is still years away. Still, those who have implemented pilots have seen positive results in supply-chain efficiencies, customer service and more. “There has been a dramatic increase in the level of interest and general knowledge about RFID technology within the last two years,” says Andrew McGrath of Manhattan Associates. “As evidenced by the success of retailers and select suppliers with their RFID initiatives, there are real benefits from the technology. But the full impact will likely not be realized until EPCs are on every pallet, carton and item within a global supply chain and this is unlikely to happen before 2010. The adoption rate is rapidly increasing and we view RFID technology as critical for organizations as they continue to globalize their supply chains.” (Graves, 2000, pp.68-83)

As the major hurdles to implementation erode, look for smaller retailers and brands to find ways to use RFID creatively, as well as larger retailers and brands using it in more in-depth ways for broader efficiencies. PRISYMID’s Richard DiNatale believes that the technology is proven in logistics, and most companies will adopt once ROI is in line with goals, as one of the biggest issues is the expense is often not worth the investment for smaller companies at this early stage. “RFID technology will be integrated into business processes as retailers continue their roll-outs,” explains McGrath. “Critical factors that will influence the continued adoption of the technology include decreasing tag prices and ratification of EPCglobal standards. Companies have been pragmatic in their methods of deployment, and now is the time for the early adopters to evaluate their ‘tipping point’ – the time when it becomes cost-effective to tag at their manufacturing source instead of at the DC just prior to shipment. Privacy concerns still top the list of must-do’s before retailers and brands will be able to fully embrace the technology’s possibilities.

Addressing privacy concerns and consumer control over killing tags is key, especially for apparel because it’s such a personal thing to consumers – it’s more intimate than the shampoo that sits in their bathroom because it goes where consumers go. All of these issues will likely be addressed as more pilot programmes are initiated and more brand marketers and retailers gain expertise and experience with the technology. And with any technology, time only leads to the evolution of benefits, better/smarter functionalities, streamlined efficiencies, cost savings, etc. Wisdom can only be acquired with time, and I think all the experimentation that we have done so far has shown us that there are still a lot of things to watch out for – unintended consequences, unforeseen implications. No matter what the benefits, or how compelling, it doesn’t make sense to rush into this headlong. (Dekker, et.al, 1998, pp. 69-77) And although RFID is in a testing and experimentation phase, experts have a strong belief that for those who invest, the payoff stands to be great. For consumers, they will also see a benefit in the levels of service that are provided by their favourite brand or retailer. It definitely has potential anything that can collapse the length of the supply chain will help apparel. So many decisions in apparel are one-shot deals – you get one buy, unless it is basics – so increasing the visibility into supply-chain status of any order, and increasing the ability to change that order before it is completely committed, in response to demand signals, is enormously valuable to the apparel industry.

In terms of the next few years, look for many new and exciting evolutions to come down the pipeline, particularly as vendors and apparel companies work together to tailor solutions to specific apparel needs. McGrath anticipates that the use of the technology for receiving at the distribution centre level will rise as more products are tagged. Because most EPC tagging in DCs is done through what he calls the “slap and ship” approach, little efficiency is actually reached at the DC level, but rather at the store level. By tagging further upstream, product will arrive into the DCs already tagged,” he explains. Once product is truly tagged at the source of the supply chain, the benefits of EPC reads will be realized at each node, instead of just the terminus as today. Most FtFID readers deployed today are fixed – either positioned at a dock door, warehouse doorway or other operational ‘choke-point’. Mobile readers are the next step and will allow us to get EPC reads while product is moved or picked to a fork truck. (Holmberg, 1999, pp.127-40)

It is says that while most implementations of RFID today centre on items are shipped, already tagged, to retailers, this will change as the next big step will be to tag at the source, not the distribution centre. This will have large ramifications for the industry and lead to huge cost savings, including in labour, as well as improved receiving and order accuracy. Other initiatives coming down the pipeline include reusable tags to lower costs for vendors, and anti-theft possibilities by integrating RFID with electronic article surveillance (EAS) for luxury type items. But at the end of the day, one of the key ingredients in seeing that RFID meets its potential is getting the apparel industry to join together and share its learning’s, identify opportunities and outline guidelines for other companies. Forums like EPCglobal have made industry participants more comfortable with exchanging information, and have confirmed that these opportunities are the most cost-effective, least risky methods of educating themselves.

“It gives people confidence and prevents everyone from reinventing the processes and implementations for themselves,” he says. “These arenas help companies avoid relearning and redoing what someone else has already discovered. The fear is that you share propriety information but more people will realize that the top five or seven opportunities all make the ‘talk list’ and they won’t be much different to anyone else’s. The broader value chain only exists on effective data sharing and the associated standards and systems that can only happen through interactions between organizations. Although companies believe they will lose their competitive advantage, the opposite is actually true. The distinction does not come in identifying opportunities, challenges or benefits, but rather in how you implement your own proprietary, customized solutions. Once the resistance and concern diminishes, the market for RFID will accelerate. Otherwise it will only stay in place. (Cavinato, 2001, pp.10-15)

Methodology

Due to the highly perceptual nature of data related to firm technological readiness, complementarity, and some aspects of logistics service quality, a survey method of collecting data was considered most appropriate. Also, the research design in case 2 required a survey of paired dyads. Thus, a mail survey-based methodology matching manufacturers to their retail partners was utilized (Anderson and Weitz 1989).

Survey method and Questionnaire

For this questionnaire we have chosen the managers in supply chain management working in Unilever and united biscuits. Questionnaire was made mainly through phone calls and few live meetings with the managers of these companies. When supply chain executives were asked about their perception of supply chain challenges, they ranked “assuring container security” as the most important challenge, over managerial considerations such as reducing inventory, reducing lead time variance, and reducing stock-outs

- What is the background of your company’s supply chain system?

- What were the main reasons of changing your supply chain system?

- What you think about RFID?

- Difference between traditional supply chain system and today’s modern RFID system

- What facilities your company is enjoying after implementing the RFID?

- Are there any flaws of security in the present RFID system?

This kind of grouping and cross-case analysis was performed for the different uses of RFID that is transaction processing with customers / suppliers, supply chain planning and collaboration with customers, suppliers, and order tracking and delivery coordination with customers and suppliers.

Interview patterns

Each interview was analyzed using the QSR NVivo 1.3 software package. The software package allowed the researcher to do open, axial, and selective coding, as is recommended by Strauss and Corbin (1998) in qualitative research studies. Themes and concepts that emerged during the analysis were compared, analyzed in detail, and combined into categories to form constructs and a theoretical framework. In addition, the principal researcher took notes on observations of a number of business discussions between the primary interview participant and his or her co-workers from various positions within the firm, toured facilities, and reviewed corporate documents (e.g., coordination mechanism process map, vendor relations manual, or contractual document), when available. The literature was also used as a secondary source during the data collection and analysis phases such that the study involved a continual referral between interview transcripts and literature findings.

Data Collection

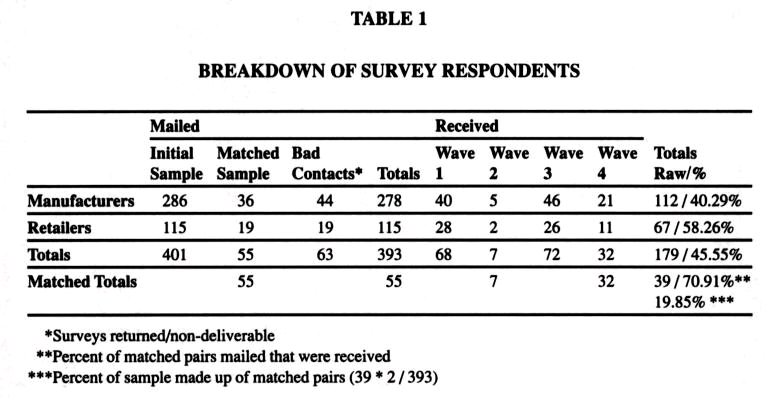

Over 50 different industries were included in the study to increase generalizability1 (Shadish, Cook, and Campbell 2007). Following sample selection, the survey was administered to targeting executives responsible for technological implementation. Names were selected from a Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals database. Surveys were mailed to senior level management responsible for managing firm to firm relationships involving technology and by electronic communication systems. If the manager was not able to answer the questions about inter-organizational technology, he/she was asked to pass the survey on to the appropriate person. Supply chain partners were matched using a snowballing technique2. Data collection started in December of 2002 and lasted approximately eight weeks ending in January of 2007. Table 1 presents a multi-wave breakdown of responses. All respondents surveyed were subject to a wave analysis employing MANOVA to check for non-response bias (examining selected scale items from each construct) (Armstrong and Overton, 2007). Each of the major survey waves was counted as a separate wave, for a total of three waves (wave two was collapsed into wave one due it its small size). Wave analysis was performed covering all relevant variables and no significant differences were found that would indicate non-response bias. Finally, we telephoned 20 non-respondents – ten retailers and ten manufacturers – and ran an ANOVA analysis of the ֺTR and LSQ items. Again, no significant differences were found. Below table obtained from (Armstrong and Overton, 2007)

Findings

Unilever

What is the background of your company’s supply chain system?

Unilever utilizes the Texas Instruments RFID technology to sustain its smart pallet system designed to progress, hold, and find its customer products in its warehouses. Transponders have been installed at the cove doors of the warehouse to find pallets that goes by through them. Subsequently, an additional transponder sends that data about the transitory transport vehicle to the computer tool. This data on the individual pallet weights stored in the computer record is utilized in matching the weight of the full load of a truck. Consequently of the RFID system, the figure of pallets handled every day has increased and the data on the movements of the bodily loads has turn out to be more reliable. In the drive for automation, today’s supply chains must provide safe and secure integration of customers, business partners, employees and suppliers into the core business processes and identity data used by a firm, all of which can be merged into new java-, HTML- and XML-based applications.

It is essential that access to automated processes and data be actively managed to prevent incidences of fraud and abuse, and to ensure compliance with privacy requirements related to use of personal data. By applying security measures to application system software and data, access to information and data repositories can be controlled and unauthorized access detected. Multiple entry points to the systems and the information required increase the headaches associated with password and access control. Users faced with the need to remember multiple passwords will be inclined to keep hard copies of the passwords near their workstations, compromising security. Additionally, lost or revoked passwords take up a considerable amount of time for operators of IT help desks, taking staff away from more value-added tasks.

What were the main reasons of changing your supply chain system?

The main reason for changing the traditional supply chain system into RFID was data that is inaccurate, redundant or inconsistent – from being held in multiple databases – greatly increases the risk of unauthorized access, or of legitimate users being denied access to business-critical data. Security measures must be applied to all linkages with existing systems to ensure that there are no breaches possible from within existing applications. This is especially significant in cases where part of the technology infrastructure is outsourced to a third party for development or maintenance. For example, where there is a transfer of any personal data among remote business partners, that data must be secured en route to ensure that it is not tampered with and that privacy requirements are upheld. An age old risk in business is the risk of not getting paid owing to disputed sales.

In addition, firms need to maintain the integrity of their supply chain communications to ensure that no contract terms are breached or data is misused, such as credit card details being compromised. This is a particular issue in supply chain interactions, which involve high levels of communication among business partners, including exchange of purchase orders and payment details. In addition, operations that rely on banks of servers and multiple instances of applications are open to vulnerabilities that include software defects, back doors and improper configurations. Any of these, if not continuously guarded against, leave a firm’s supply chain operations vulnerable to attack. (Cooper, 2003, pp. 13-24) Threats to physical security of systems involved in the supply chain include unauthorized access to premises. In addition, interruptions to business caused by failure of service can be problematic: reliance on automated systems is dependent upon those systems being up 100 percent of the time, with data fully backed up to maintain the integrity of communications. Companies need to ensure that they have comprehensive emergency procedures in place.

What you think about RFID?

RFID will play a vital role in the performance of our organization. Vendors of supply chain technology are increasingly adding RFID access capabilities to their offerings to allow efficiencies enabled by automation of business processes to be extended to all users regardless of location, including those on the factory floor and to logistics carriers. This trend has been increased by the movement towards Internet-enabled applications, where no more than a browser or WAP-enabled interface is required to access supply chain applications. To facilitate these developments, companies are increasingly using Wi-Fi-enabled (Wireless Fidelity) open-access networks. With such networks, security is an issue. A recent survey by Computerworld magazine indicated that 30 percent of American companies have identified rogue access points to their wireless networks. These can provide back doors past firewalls into companies’ networks. Further problems with wireless device connectivity include the physical security of such devices.

Handheld computers containing password and other access information can be lost; alternatively, when plugged directly into a computer, they can bypass firewalls and anti-virus software, leaving the network vulnerable to attack. (Svoronos 2004 57-72) A new container security initiative activated by the US Customs Service concerns security from another angle: the need for companies to comply with new regulations for electronic filing of cargo manifests so as not to breach US homeland security requirements. Whereas previously import documentation was not checked until shipments arrived at US ports, under the new container security initiative, shippers and carriers must electronically transfer full line-item detail in their manifests to US customs officials 24 hours before the cargo is loaded at its point of origin. Failure to do can lead to widespread delays and increased shipping costs. Since logistics and fulfilment generally account for 10 to 20 percent of the end cost of a product, these new security requirements can place a large burden on the overall performance of a company’s supply chain and its efficient management.

Difference between traditional supply chain system and today’s modern RFID system

The major difference we have come to know is the privacy and speed of work. Enhancing security in supply chain operations revolve around planning, policy and procedures. While technology is an essential tool for increasing security, its use should be closely aligned with comprehensive security policies that should be developed by every organization and which should be communicated effectively to all parties involved. Ideally, a chief security officer should be designated to centrally control all security issues and to ensure that measures taken are effective. (Jia, et.al, 2005, pp.48-61) Identity management systems can be used for authentication of users – especially de-provisioning when employees leave the company. The use of certificates for authentication establishes the identity and trustworthiness of any party willing to connect with you; this is especially significant as online identities can be faked. To be effective, identity management software should be employed to align security procedures with business processes.

Some of the main features of identity management technologies are that they control access to systems through administration of passwords, user names and credentials, function-related access levels and authorization, and user authentication. The use of single sign-on mitigates many of the problems involved with storing and remembering multiple passwords. It use has been shown to lead to a 33 percent reduction in help desk call volume and a 32 percent increase in overall security. Encryption and certification should be used to validate all users and to ensure the integrity of all messages sent through the supply chain. Security policies should be put in place so that an administrator can validate all certificates and prevent misuse, and a protocol should be developed for revoking and communicating compromised certificates. Different levels of certification should be used for different levels of authorization. In addition, centralized security policies should be put in place for use of encryption keys by personnel and a secure back-up storage facility should be designated for maintaining encryption keys. (Sitkin, 2004, pp.537-68)

What facilities your company is enjoying after implementing the RFID?

As all data involved in the running of the supply chain should be integrated into back-end systems and databases. A recent survey indicates that consolidation can lead to a 44 percent increase in consistency, a 36 percent increase in accuracy, and a 33 percent increase in actual security. Synchronization software can also be used for maintaining consistency of data – one database can be designated as the master source of all data, or different databases can be made responsible for different tasks and the synchronization of the resulting data. Provision of self-service capabilities for users can also mitigate this problem as they can maintain their own accounts and are responsible for ensuring that all data is up to date. (Houlihan, 2005, pp.22-38) At the very least, secure socket layer technology should be employed to ensure that all data is physically secure as it is communicated across the supply chain. When supply chain partners are tightly integrated into a firm’s supply chain – for example, when they have access to stock level data in order to manage replenishment themselves – virtual private network technology should be used to ensure that the network is private and secure.

Are there any flaws of security in the present RFID system?