Abstract

Globally, the recession has had a negative impact on most businesses and governments. Consequently, the recession has forced many companies to downsize their operations by laying-off workers and reducing the scope of their investment programs. The recession has equally forced governments to reduce “unnecessary” spending and bail out struggling businesses. Likewise, the recession forced consumers to contend with high unemployment rates, inability to pay debts and a reduction of social welfare support. Social enterprises have however surprised many people by registering a positive outcome during the crisis. Indeed, unlike many profit-making businesses, social enterprises have weathered the effects of the financial crisis relatively better than most ordinary businesses. During the recession, these organisations have sustained their incomes and grown in equal regard. This paper explores the factors that have led to the positive performance of these social enterprises by analysing five social enterprises in the UK – Co-operative bank, John Lewis partnership, and Cafe Direct.

Notably, this paper establishes that social enterprises operate through a powerful model of governance and capital structure, which informs much of its success. The member-owned business model especially creates several benefits that such enterprises exploited to survive in the recession. Despite the positive performance of social enterprises, this paper proposes that the government should provide a supportive environment for social enterprise so that they may continue to succeed and support its vision of a “big society.” To this extent, social enterprises will continue to provide an admirable business model that other organisations may emulate.

Introduction

News about the effects of the economic recession has dominated mainstream media for most parts of the years 2008, 2009, and 2010. Today, the focus has been on how economies in the developed world may recover from the effects of the economic downturn. Indeed, many observers are waiting to see how developed economies will emerge from bad economic situations, like, “rising unemployment, decreased consumer spending, low gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates and other macroeconomic indicators” (Clara 2010, p. 1). These bleak macroeconomic indicators explain the lack of public faith in the running of macro-economic institutions. For example, Clara (2010) says the 2008 financial crisis caused the loss of faith in the management practices of chief executive officers (CEOs). Indeed, many people hold a firm belief that corporate greed explains the collapse of the 2008 global economy. The poor performance of the global economy had far-reaching implications on the global economy. In fact, many people would expect the recession to have far-reaching implications for the non-profit sector, which mainly depends on donations and charities to survive. In detail, many people would expect the poorly performing economy to have caused a significant strain on the flow of donations and government grants to non-profit enterprises as companies and governments struggle to mitigate the effects of the global economic downturn. However, this was not the case.

One notable group of organisations (social enterprises) proved that they could withstand the effects of the economic downturn. According to UK’s classification of social enterprises, social enterprises are organisations that operate with the primary goal of meeting social objectives (Nyssens 2006). The UK government also regards businesses that also reinvest their profits to fulfill social goals as social enterprises (Nyssens 2006). Morley (1968) expounds this definition by saying that social enterprises are not organisations, but activities. Therefore, organisations that decide to engage in such social activities are social organisations. These activities make them unique to other organisations because social enterprises have unique characteristics that include a high degree of autonomy, an explicit quest to promote community well-being, and a decision-making power that hinges on capital ownership, which distinguishes them from other organisations (Urs 2010).

Certainly, interesting twists of events show that social enterprises did not experience the same misfortune that hit profit-making entities in the UK. To understand how this group of organisations managed to do so, it is crucial to mention that social enterprises are non-profit entities that operate in different sectors of the UK economy, including the housing sector, health sector, education sector, and the renewable energy sector (Allinson, 2011, p. 14). There are more than 62,000 social enterprises in the UK (Allinson, 2011). Datamonitor (2011) posits that these enterprises receive revenues of about 32 billion Euros (yearly). Although a small representative sample of social enterprises in the UK, “Traidcraft, the Eden Project, Big Issue and Jamie Oliver’s 15 restaurants” (Allinson, 2011, p. 14) represent some of the most common social enterprises in the UK.

Regardless of the economic recession, more than half of all social enterprises in the UK posted improved turnovers during the recession (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). Conversely, only about 20% of the total social enterprises in the country posted reduced turnovers (Datamonitor 2011). Interestingly, while many people may expect profit-making businesses to have a higher turnover than social enterprises, only about 28% of such businesses posted increased turnovers during the recession (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). Besides increased turnovers, many social enterprises registered growth and sustained business activities throughout the recession. A study by Akhtar (2011), to investigate the effects of the recession on businesses in Bradford, showed that, compared to small businesses, social enterprises were more resilient throughout the recession than ordinary businesses. Moreover, he explained that about four in every ten social enterprises recorded improved economic fortunes throughout the recession, while only about two out of every ten small businesses reported the same economic outcome (Akhtar, 2011). Relative to this view, a 2010 article by Martin (2010) reported that, “According to Society Media’s SE100 index, the top 100 social enterprises – companies which put all, or part, of their profits into a social or environmental cause – grew by almost 79% in the year to March 2010” (Martin, 2010, p. 1). The positive performance of social enterprises show that they have registered improved growth even as the recession prevailed.

Compared to small businesses, a study sponsored by the Cooperative Bank (UK) showed that social enterprises outstripped the performance of small businesses during the recession (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). For example, Villeneuve-Smith (2011) affirmed that the growth of social enterprises was bigger than small and medium enterprises (SMEs), during the recession, because the art of social enterprise growth outstripped SMEs by 58% to 28%. The level of business confidence in social enterprises also outstripped the level of business confidence among SMEs when Villeneuve-Smith (2011) reported that the level of business confidence among social enterprises was 57%, while the business confidence in SMEs was only 41%. A key indicator of the positively performing social enterprise sector was the level of innovation within the sector. Villeneuve-Smith (2011) says that about 55% of social enterprises produced new products in the market, while only about 47% of SME’s were innovative. Datamonitor (2011) explains that the positive progress of social enterprises (compared to profit-making enterprises) show that social enterprises project a more secure future than ordinary businesses. The above developments also show that there was increased investment in social enterprises, even as investors remained pessimistic regarding the global economic outlook (in the recession).

This paper aims to explain the resilience of social enterprises in the wake of economic recession. In detail, this paper seeks to understand what factors informed the resilience of social enterprises during the uncertain economic times. This analysis will also show the aspects of social enterprises that make them highly successful. Similarly, this paper seeks to understand why social enterprises still attract customers even in the middle of an economic crisis, and what measurable extent did the recession impact social enterprises. Lastly, in a more general sense, this paper explains if social enterprises are more competitive in their industries by virtue of containing superior aspects of business governance.

Purpose of Study

Social enterprises play a vital role in sustaining the economy of the UK. Foale (2013) affirms this statement by saying that, in the UK, social enterprises account for more than 99% of the country’s businesses (Foale 2013). Moreover, social enterprises are responsible for close to 50% of the turnover witnessed in the private sector (Foale 2013). Considering the importance of social enterprises to the country’s economy, undoubtedly, businesses and governments need to provide the right support for these enterprises to continue to thrive even in poor economic times.

Amid the economic uncertainties caused by the weak global economy, Clara (2010) says that the nature of business for social enterprises place them in a special position to weather the effects of a poorly performing global economy. In the same lens of analysis, Foale (2013) adds that the focus on social enterprises could be the key to uncovering the solution to economic recovery. The ability of social enterprises to make profits and promote social development informs the special focus on social enterprising. According to Clara (2010), these abilities place social enterprises in a strategic position where they can exploit opportunities that arise from the economic downturn. Therefore, by demystifying the factors that caused social enterprises to be resilient during the crisis, it is easy to achieve a clearer picture of how other organisations may improve their internal resilience in economic crises.

To achieve this purpose, this paper embarks on detailed literature review that explores what other researchers have found regarding the resilience of social enterprises in the 2008 financial crisis. Key parts of the literature review include an understanding of social enterprises in the UK, how the recession affected these social enterprises, and an understanding of the structural differences between social enterprises and for-profit businesses. To further understand these structural differences, the literature review further indulges into financial structure differences, business sector differences, legal structure differences, and business model differences that distinguish social enterprises from other types of businesses. These differences also partly explain why the 2007/2008 financial crisis minimally affected social enterprises. Lastly, the literature review explores the main factors that may have contributed to the success of social enterprises through an understanding of the shift in investor psychology, increased demand for social enterprise services, and the positive image that social enterprises enjoy. The structure of the literature review seeks to answer the following research questions.

Research Questions

- How do social enterprises compare to their for-profit rivals during the recession?

- Using profit as the measurement of success, what aspects of the management of social enterprises have made them more successful?

- How have they continued to attract customers to their shops despite falling numbers of patrons during the recession?

- To what measurable extent did the recession affect social enterprise activities?

- In a broader sense, are social enterprises more competitive in their sector/industry by virtue of containing positive aspects falling into one of the questions above?

- What theoretical bases and models inform the business practices of social enterprises?

- To find out the lessons that social enterprises may provide to for-profit businesses in overcoming the effects of financial crises

Literature Review

This chapter explores the underpinnings of the resilient social enterprise model as a cycle diagram that explains why social enterprises have been resilient in the wake of the financial crisis. In detail, this literature review explores the unique structural differences between social enterprises and for-profit businesses and the factors that may have contributed to the success of social enterprises (shift of investor psychology, increased demand for social enterprise services, and positive image of social enterprises) as the main reasons why social enterprises have remained resilient throughout the financial crisis. The cycle diagram below explains the interconnection of these factors

The above cycle diagram explains the interconnection of different components of this literature review and the role of these components in explaining the resilience of the social enterprise model that most social enterprises have used to run their operations. In part, this relationship provides a theoretical understanding of how social enterprises weathered the financial crisis.

How the Recession Affected Social Enterprises

As mentioned in this paper, most social enterprises in the UK have posted increased turnovers during recessions. About 56% of such enterprises have witnessed increased turnovers (Hudson 2012). According to Fight back Britain (cited in Villeneuve-Smith 2011), the rate of turnover of social enterprises increased throughout the recession because in 2009, the median turnover of social enterprises was £175,000, but by the end of 2011, this figure increased to £240,000 (traditionally, the turnover for social enterprises has been significantly lower than profit-making enterprises). However, throughout the recession, most social enterprises reported a higher turnover rate than most profit-making enterprises. For example, Nicole (2009) says social enterprises reported a higher turnover rate of 33%, compared to 23% for SMEs. The Social Enterprise Barometer (cited in Nicole 2009) also confirms this high turnover by saying that, “the mean annual turnover of SEs was £471,000 – substantially lower and two-thirds of the average for SMEs (twice as large a proportion of SEs as SMEs earned less than £99,000 – 30 per cent and 15 per cent respectively)” (p. 15).

Social enterprises also posted a higher rate of employee growth within their human resource departments, during the crisis (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). During the recession period, social enterprises also recorded a higher level of expansion in employment opportunities, compared to civil society organisations and profit-oriented businesses. Part of the reason for the difference in the performance for social enterprises and profit-making enterprises during the recession is the labour-intensive nature of social enterprises. It is also crucial to mention that most social enterprises are different from other profit-making organisations because they often pursue several goals (at the same time), as opposed to the single goal of increasing their baseline operations. Nonetheless, it is also crucial to mention that not all social enterprises work in one way. Moreover, their patterns of operations are often changing.

Even though social enterprises seem to perform better than profit-making enterprises and civil society organisations, Athanasia (2012) cautions against generalising such findings across all sectors of social enterprising. In detail, he attributes the differences in performance of social enterprises and other businesses to the economic sectors, and not necessarily the social enterprises (Athanasia 2012). By extension, this caveat means that the recession hit some economic sectors harder than others were.

A research study published by Villeneuve-Smith (2011), which showed that social enterprises had a 20% higher likelihood of surviving in the next five years, as opposed to SMEs, also affirms the resilience of social enterprises during the recession. The same study also established that social enterprises posted a higher growth rate of about 17% more than ordinary businesses in the UK (social enterprises managed to sustain this high rate of growth during the recession) (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). Athanasia (2012) has reported similar levels of growth through a social enterprise coalition study. In fact, the social enterprise coalition study showed that in 2009, social enterprises posted a high rate of turnover than other types of businesses in the UK (Athanasia 2012). For example, the study showed that more than 50% of social enterprises reported increased turnovers during the recession, while more than 60% of charities reported a reduction in their turnover rate (Athanasia 2012).

The above statistics do not imply that all social enterprises were unaffected by the recession – about 20% of social enterprises reported reduced turnovers (Hudson 2012). However, compared to profit-making enterprises, about 40% of such businesses realised reduced turnovers because of the recession. Similarly, only about 28% of such organisations posted increased turnovers (Hudson 2012). Nonetheless, the rate at which the recession has affected social enterprises and small businesses depend on the industry in focus. For example, Hudson (2012) says that the construction industry was the most affected by the recession and therefore, SMEs and social enterprises (affiliated to this sector) posted the worst economic outcomes.

Structural differences between Social Enterprises and For-profit Businesses

There is a common belief that social enterprises are antecedents of religious foundations or public sector organisations. However, very few social enterprises belong to these organisations. Nicole (2009) says that while many social enterprises have remained true to their goal – social enterprising, some social enterprises started as philanthropic institutions (about one in every five social enterprises started as charities). Although the origins of social enterprises provide few pieces of information about their resilience in the financial crisis, it largely explains the business model that such organisations use to run their operations. To understand the main factors that influence the success of social enterprises in the recession, it is important to understand why social enterprises are unique to other enterprises. More specifically, it is crucial to understand how social enterprises are different from SMEs and other profit-making organisations.

Social enterprises do not differ much from profit making enterprises in the sense that both enterprises compete for the provision of goods and services to the people (Nyssens 2007). However, social enterprises are unique to SMEs because they normally reinvest their profits to service environmental and community interests (Chell 2007). The following diagram shows the difference between social enterprises and profit-making enterprises on a pendulum of factors that differentiate the two groups of enterprises.

On one side of the divide, social enterprises differentiate themselves from profit-making enterprises because most of their actions are charitable and aim to have a social impact. On the other side of the divide, enterprises that operate with a financial motive, in the end, fulfil a financial motive. Some of their actions may however still be socially responsible (like giving profits to charity). Profit-making organisations therefore reinvest their profits to serve the interests of their owners and shareholders. Social enterprises also have a keen interest in the way they do their businesses because, besides their earnings, these enterprises are highly concerned about their social and environmental performance (Chell 2007).

Researchers have used the above understandings of social enterprises to explain why they weathered the economic effects of a poorly performing global economy (Martin & Thompson 2010). Many of the reasons proposed by researchers focus on the structural differences that social enterprises have with profit-making entities (Martin & Thompson 2010). Indeed, the structural differences between social enterprises are for-profit businesses partly explain why social enterprises have been resilient during the recession. This section of the dissertation focuses on the distinguishing features of social enterprises by promoting their unique financial structures, legal structures, sector concentration, and business models as the main structural differences that inform their uniqueness.

Business Model Differences

Social enterprises differ from SMEs and other profit-making organisations because commercial concerns do not primarily motivate them. Indeed, as this study shows in later sections of this dissertation, social enterprises always strive to remain true to their cause – promotion of social and environmental goals. The commitment to these goals always affects the way these enterprises make their decisions and how they conduct their businesses. For example, through the commitment to uphold their social and environmental goals, some social enterprises become highly dependent on grants, while others adopt a more market-oriented model for conducting their operations (Nicole 2009).

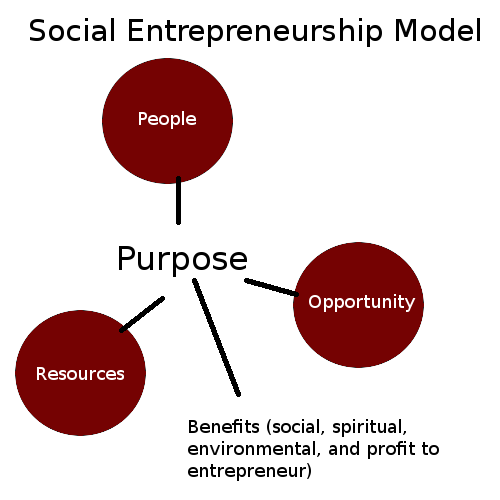

There is no standard operating model that social enterprises use to operate. Instead, different social enterprises use different business models that depend on different motivations for funding. However, the common social entrepreneurship model comprises of three main pillars as described below – people, opportunity, and resources.

The purpose of social enterprising is at the centre of these three pillars. In other words, by using organisational resources to exploit market opportunities, social enterprises create value for the community by providing immense social, spiritual, environmental, and financial benefits to their stakeholders (as described above). The provision of these benefits always conforms to the purpose of the enterprise. Uniquely, social enterprises also have a special drive to make a change in the society by achieving different social missions and upholding different social values. In addition, unlike profit-making organisations, the objectives of social enterprises are more relaxed and clear. For example, unlike profit-making companies that strive to grow even during recessions, social enterprises have a more flexible plan that allows them to shelve their growth plans when the time is not right (Kolasa, Rubaszek & Taglioni 2010).

The business models adopted by social enterprises therefore do not make much sense for profit-making companies, especially because the design of a social enterprise intends to realise community improvements, while profit-making enterprises want to make a profit. Therefore, unlike profit-making enterprises, which prefer to reinvest their profits in activities that would generate more profits, social enterprises invest their profits in activities that promote social goals. For example, Urban Works, a social enterprise in the US, has strived to promote social goals at the expense of economic goals (Kolasa, Rubaszek & Taglioni 2010). The enterprise mainly focuses on highlighting the plight of disadvantaged workers by employing them in the organisation. This strategy has increased the number of economically disadvantaged workers in the organisation to more than 70% in 2001 (most of these workers were drug and alcohol addicts) (Kolasa, Rubaszek & Taglioni 2010). Similarly, 5% of the workforce comprises of people who were initially homeless (Kolasa, Rubaszek & Taglioni 2010).

Urban Work provides computer skills to this group of people so that they may use the same skills to get better jobs (Kolasa, Rubaszek & Taglioni 2010). However, like profit-making entities, Urban Work generates profits internally and does not depend on external parties to give them donations, or grants. Nonetheless, the hiring and recruitment model adopted by the organisation makes no sense for organisations that work for a profit. In detail, the company helps to nurture the skills of its employees in job descriptions that it does not require. Therefore, the organisation is undisturbed by its high turnover of employees (a model that would not be supported by organisations that work for a profit).

The commitment by social enterprises to promote social goals at the expense of profit-oriented goals has received some backlash from observers who believe that social enterprises exist because of their role in solving some of the problems that profit-making enterprises cannot explicitly solve (Jennifer 2009). Therefore, in their view, both types of organisations should not operate in overlapping realms of operation. Similar to this view is the opinion that the corporate goals of profit maximisation do not coagulate with the corporate goal of charity giving. To some people, the ability of social enterprises to be in-between (profit-making and non-profit making) informs its ability to withstand the pressures of recessions (Jennifer 2009).

From the unique business model that underpins the activities of social enterprises, the analysis on the social enterprise model shows that most social enterprises strive to promote a business model that primarily works to promote community-centred goals, at the expense of profit-maximisation goals. This is why this section of the dissertation outlines that the purpose of social enterprises mainly stems from the focus on people, resources, and opportunities. This unique business model differs from the business models that for-profit businesses adopt because social enterprises promote a greater social cause, as opposed to a profit-maximisation cause. From these differences, social enterprises boast of a special financial structure that rivals most successful financial structure models for successful for-profit businesses.

Financial Structure Differences

One area of structural difference between a social enterprise and a profit-making enterprise is the mode of financing. Unlike profit-making enterprises, which depend on profit margins for sustaining their finances, social enterprises derive their profits from governments, charities, and philanthropic bodies (Martin & Thompson 2010). In fact, small enterprises have various options for sourcing their finances. A common option for social enterprises to source finances during a recession is bootstrapping. Bootstrapping simply involves the acquisition of vital resources that are essential to the survival of the enterprise (Moizer & Tracey 2010). Through a different perspective, people may understand bootstrapping as a social response to an economic problem (only happens when enterprises feel seriously constrained). Several researchers, including Aldrich & Martinez (2001) and Ebben (2009) say that many social enterprises use bootstrapping (among a series of other options) to get financed.

The sheer diversities of social enterprise investors mean that social enterprises have a reliable pool of investors where they draw their capital and labour. Relative to this assertion, Ruth (2008) claims that social enterprises rarely lack money to undertake their operations. This does not however mean that financial problems are not part of their daily challenges because they are. Interestingly, this problem does not derail them from undertaking highly ambitious projects. However, if this problem persists in the end, it may be difficult for such enterprises to sustain their activities (Ruth 2008). The bottom-line understanding of this situation therefore premises on the fact that social enterprises require adequate resources to sustain their activities (Moizer & Tracey 2010). In times of recession, it is therefore advisable that such businesses adjust their operations to stay afloat.

From this analysis, social enterprises enjoy a wider pool of financing from institutions and organisations that do not necessarily invest to derive a profit. Such institutions are charities, governments, and philanthropic bodies. This pool of investors is also more reliable than investors who derive their influence from market dynamics. Therefore, when social enterprises receive funding from this group of investors and conventional investors (who are primarily motivated to make a profit), they enjoy a greater diversity of financial structure than for-profit businesses. The diversity of their financial pool however comes from the business sector differences that distinguish social enterprises from for-profit businesses.

Business Sector Differences

The sector differences between social enterprises and SMEs stem from the differences in their main functions. Since social enterprises are community-oriented, they are more concerned with community development and the promotion of social welfare programs (unlike for-profit organisations). Even though this paper establishes that social enterprises are found in different sectors of the economy, most social enterprises are found in primary industries (such as agriculture), while there are few social enterprises in some “technical” industries (such as manufacturing) (Nicole 2009). Mainly, people-oriented businesses tend to have a higher concentration of social enterprises. In fact, in certain industries, like the hospitality industry, the number of social enterprises usually matches the number of SMEs. However, in some people-oriented sectors, such as health and education, the number of social enterprises almost triples the number of SMES. Albeit social enterprises tend to be community-oriented, they are highly unlikely to be involved in international development and faith-based activities (Nicole 2009).

While social enterprises mainly focus on community-centred business sectors, for-profit businesses are mainly concerned with the provision of goods and the development of exclusive services. For example, this paper already shows that there are very few social enterprises operating in manufacturing industries because such business sectors are relatively unrelated with the goal of service delivery (which is at the core of community development). Comprehensively, because social enterprises have a wider social objective of promoting community development and social welfare programs, they receive a different type of attention from investors who are primarily motivated with the same concerns (community concerns) – hence the dynamic funding structure. Their unique business sector differences also attract governments in the same manner because governments are also concerned with the goal of improving the wider “public good.” Since these social enterprises operate in the same market as profit-making enterprises, their vulnerability to market factors and unfair competitive practices has forced the government to develop special legal structures where these social enterprises operate.

Legal Structure Differences

According to Clara (2010), social enterprises have been resilient in overcoming the adverse effects of the recession by benefitting from government support. This is why she says, “Beyond entrepreneurial skills and business strategies, the long-term success of social enterprises hinges on the will of governments to enact policies that encourage the growth of innovative social ventures” (Clara 2010, p. 5). The UK government strongly champions the goals of social enterprises because it perceives them as a key pillar to the recovery of the national economy (Clara 2010). The government also considers social enterprises as a key pillar of social reform in the UK. Legally, the UK has transformed its economic policies to promote the development of social enterprises in several ways. For example, the UK government launched the Office of the Third Sector to support the activities of social enterprises (Defourny 2004; Pete 2012). In addition, existing legal structures uphold the principle of transparency in the management of social enterprises, to mean that there are minimal possibilities of corruption to thrive in social enterprises (Armstrong 2010).

Social enterprises have clearly outperformed the private sector in convincing the government to promote its activities as the better alternative to the provision of public goods and services. One area that has elevated social enterprises as the better alternative to private sector intervention is the fact that they have demonstrated a long-term commitment to community well-being, as opposed to private sector enterprises, which promote financial gain (Roake 2009). Moreover, social enterprises have demonstrated to the government that selecting private enterprises to support community initiatives mean they will incur a higher cost of doing business, as opposed to seeking their services, which are cheap (Armstrong 2010). However, the fact that social enterprises are mainly future-oriented has dented the prospects of gaining full political support because politicians are mainly concerned about their re-election. Therefore, if they give their support to organisations that intend to undertake future projects that will benefit future generations, there is no guarantee that they will benefit from such initiatives. They are therefore likely to be hesitant to provide their full support to such enterprises. Nonetheless, this challenge has offered minimal obstacles to prevent the growth of social enterprises.

Allinson (2011) partly explains why social enterprises receive immense government support by stating that the mission and vision of social enterprises closely resemble the vision and mission of the government. In other words, both groups are interested in promoting public good – the “big society” vision. Similarly, both enterprises serve an instrumental role in controlling public spending and reducing the national budget deficit (Allinson 2011). Since the government and social enterprises share a common purpose, many legal documents that consolidate their operations have been forthcoming. For example, “social enterprise – a strategy for success,” and “social enterprise action plan – scaling new heights” are examples of two documents that have emerged from the efforts by legislators to increase the symmetry between social enterprises and the government (Allinson 2011). These two documents have so far managed to set out a series of objectives that include, “creating the appropriate regulatory and legal environment; delivering support for business improvement, and raising awareness and the visibility of the SE sector” (Allinson, 2011, p. 14). Analysts derived these objectives from the “social enterprise – a strategy for success” document (Allinson 2011). The 2006 Action plan, which introduced later, only added to the objectives of the first document by encouraging more elaborate actions from the government to the private sector including,

“The promotion of higher level training in the sector; specific funding to improve the provision of SE business support; an investment fund; training to promote improved access to finance generally, and a cross-departmental Third Sector plan, to encourage closer working between government and Civil Society Organisations (CSOs)” (Allinson 2011, p. 14).

The above legal foundations created the right environment for the formulation of the Open Public Service Paper, in 2011, which provided social enterprises with better terms of relations than those outlined by previous governments (Allinson 2011). The paper provided an opportunity for social enterprises to seek opportunities for providing goods and services that the central government was supposed to provide. Notably, public service workers were encouraged to join (or start) social enterprises and use their skills for the betterment of the society. The government was in its part supposed to support the entrepreneurs by reducing bureaucracy, thereby helping the enterprises to be more efficient and responsive.

These government-SE initiatives bore more fruits through the Localism Bill 2011, which provided new community rights for members of social enterprises to own property and use them for the betterment of the wider society (Allinson 2011). Under the same legal provision, the government mandated local Councils to help community establishments that faced prospects of closure, while social enterprises were also empowered to question “dangerous” decisions made by the councils, which could affect community well-being (Allinson 2011). These initiatives stem from the paradigm shift in the provision of goods and services in the community, especially because more people are convincingly coming to accept that the era of “big government” is not working because the government cannot be able to cater for the well-being of everybody (especially vulnerable groups).

Government support to social enterprises has also eloped into seeking financial support for these enterprises. Allinson (2011) observes that financial support is a key factor for the development of social enterprises and governments have played an instrumental role in ensuring that such enterprises enjoy some financial security. Through this commitment, the government established the Enterprise Finance Guarantee fund to support social enterprises (Allinson 2011). This guarantee also roped in several high street banks in the UK, which also offer financial support to social enterprises. Relative to this initiative, Allinson (2011) says, “The intended increased role for SEs is to be supported, at least in part, by raising the levels of finance earmarked for CSOs, as announced in Growing the Social Investment Market: A vision and strategy for 2011” (p. 15). Additionally, Allinson (2011) said, “This includes the new big societal capital, bringing together £400 million from dormant accounts and £200 million from Project Merlin banks, to make more investment capital – including leveraged private sector investment – available to the SE sector” (p. 15). Other initiatives that the government has introduced to support social enterprises include the use of charitable assets to foster the expansion of capacity and growth for social enterprises.

The policy-making processes for supporting social enterprises have generally occurred outside the periphery of the conventional policy-making process for profit-oriented businesses. Through this distinct policy framework, the government has committed itself to redefine the way businesses access information and undertake their daily activities. Through certain initiatives, such as the introduction of the regional growth fund, the government has committed itself to support social enterprises because their goals align with the government’s vision of a “big society,” where uneven distribution of public services and goods do not sideline vulnerable communities (Allinson 2011). This commitment creates a situation where there is little over-reliance on government programs for the sustainability of the community.

The US government has also followed in the footsteps of the UK government by renewing its commitment to support small social enterprises to achieve their goals. For example, in 2009, the American government established the Social Innovation Fund to support small social enterprises that have a high impact on the community (Allinson 2011). Most of these social enterprises have participated in several community-building activities that span through different sectors, including education and health. These enterprises have also created economic opportunities for local communities. Through the commitment of these governments (UK and US) to support social enterprises, they have both demonstrated that they are dedicated to finding innovative solutions to solving most social problems that plague the society. Comprehensively, the legal structure differences between social enterprises and for-profit enterprises show that the commitment by western governments to support social enterprise activities largely come from their commitment to formulate supportive policies that assist such organisations to flourish in a competitive business environment. These legal frameworks have contributed to the development of a vibrant social enterprise sector.

Factors that May have Contributed to the success of Social Enterprises

Shift of Investor Psychology

In an article designed to promote increased investments in social enterprises during recessions, Clara (2010) said that many recessions cause a significant shift in the psychology of investors. For example, the 2007/2008 economic crisis showed how investors could abruptly develop mistrust to organisations that seem “profit-hungry.” These poor perceptions of such enterprises stem from poor leadership among corporate managers whom, “actively traded innovative and packaged assets while passing the risk to unassuming parties” (Clara 2010, p. 3). Such poor corporate practices have caused many investors to doubt obscured financial products that these managers sell to them. However, as Clara (2010) observes, the poor perception of profit-making enterprises transcends financial products alone. To support this claim, Clara (2010) says that at the height of the recession, the huge bonus payout that AIG paid to its employees bothered many Americans. Similar sentiments exist in the UK, where Clara (2010) reports that more than 70% of UK citizens lost faith in the management of profit-making organisations. The sudden change of attitude regarding the management of profit-making enterprises means that many companies are looking to invest their money in alternative investments – social enterprises. Again, to support this claim, Clara (2010) says, “In the current period of economic gloom, social enterprise offers a haven for investors who are overwhelmingly dissatisfied with the traditional private sector” (p. 3).

The shift of investor psychology during recessions therefore provides an opportunity for social enterprises to market their financial benefits to investors who may be more than willing to entrust their money with them. The shift in investor psychology therefore creates a great opportunity for social enterprises to grow and expand their activities. An analysis of Cooperative bank shows that social enterprises can effectively exploit the opportunity created by social enterprises to expand their operations. Indeed, the bank reported a 70% hike in its profits and a 40% increase in deposits throughout the years 2008/2009 (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). Cooperative bank has been able to sustain this positive financial reporting, although it follows strict ethical investment policies and differentiates itself from profit-making enterprises by focusing on the goal of promoting financial stability. This way, the bank believes that it will help investors and community groups to derive social benefits from their investments. Through its financial reporting, the bank credits its growth and expansion projects to the economic crisis by saying that the recession helped to improve investor confidence in the bank’s activities. To explain the relationship that most recessions have on social enterprises, Clara (2010) argues,

“While the correlation between the economic downturn and social investment is not necessarily indicative of a causal relationship, the unexpected results of impressive financial growth amid recession suggest that the poor economy may be indirectly benefiting social enterprise by changing investors’ attitudes” (p. 3).

Increased Demand for Social Enterprise Services

In times of economic recession, there is always an increased demand for the services of social enterprises. This increased demand for social services mostly stems from the increased demand for social services among vulnerable groups (Gary 2009). For example, recessions increase unemployment levels and reduce government-funded social benefits. Therefore, many people turn to social enterprises to support them through recessions. This leads to a greater demand for social services (Borzaga 2001).

In the same manner that most recessions weaken a section of the population, recessions also weaken profit-making enterprises and non-profit enterprises alike, and thereby adding to the pressures that social enterprises get during such bad economic times (Gary 2009). Indeed, the 2008 recession forced many profit-making organisations to cut back. “As a result, many private companies scaled down their commitments to socially responsible initiatives, as evidenced by firms’ withdrawal from affordable housing projects, inner-city healthcare provision, social care services, and related areas where margins are tight” (p. 4). Even though private enterprises ordinarily addressed most of the issues that profit-making enterprises could not address, the recession did not spare the private enterprises either. A study by PwC affirms this fact by reporting that most charity organisations projected they would realise reduced incomes in the recession, as they feared a reduction in donations and grants throughout the crisis (Gary 2009).

History also shows that many social enterprises receive increased requests from people who cannot pay for their bills or sustain other household expenses to help them (Yang 2012). Unfortunately, many non-profit organisations have trouble when trying to help the needy because they have their financial problems as well. Since social enterprises manifest as a hybrid entity of profit-making and non-profit making institutions, they are often in a better position to meet the social and financial needs of vulnerable populations. This situation offers social enterprises with an opportunity for expanding their roles in the society, as they had to solve issues, which were not in their scope of duty. According to the Cooperative Bank, some of these additional tasks include, “the needs for job creation, economic development, and financial stability in underprivileged communities” (Villeneuve-Smith 2011, p. 4). More affirmatively, Gary (2009) says, “70% of social enterprises expected the social and environmental need that their firms addressed to increase, with 41.4% of firms expecting these needs to increase a lot in a foreseeable future” (p. 4). Gary (2009) also says that empirical evidences about social enterprises show that these enterprises are exploiting the opportunities created by the recession. A recent economic survey showed that many social enterprises perceived the economic crisis as an opportunity, as opposed to a threat (Gary 2009). The proportion of people who perceive the recession as an opportunity is about 36%, while the people who perceive the recession as a threat is a paltry 21% (Gary 2009).

Albeit there are many evidences that show how the recession provided an opportunity for existing social enterprises to expand their scope of operations, it is also crucial to highlight the fact that a regressing economy also provides increased opportunities for new social enterprises to come up. Indeed, as is the situation in most recessions, poor economic conditions create the right conditions for the development of the entrepreneurial spirit. Consequently, many social enterprises develop through recessions. For example, in a regressed economy, social enterprises are able to attract new labour from individuals who are unable to get job opportunities in other firms by settling for jobs that pay less, but add value to the society. Since the economic downturn hit the UK, there have been an increased number of applications for social enterprise start-ups (Gary 2009).

Globally, the link between increased entrepreneurship and a regressed economy is common. The Wall street Journal (cited in Gary 2009) explains that increased entrepreneurship activities mainly stems from a quest by unemployed workers to find something to do. Indeed, in late 2008, the Wall Street Journal predicted that in 2009, there would be an increased number of new enterprises in developed economies, which were most affected by the recession (Gary 2009). This happened. This trend also informs the increased need for social enterprises during recessions. Furthermore, some professionals who are also unable to get well-paying jobs during recessions decide to start new social enterprises as a personal contribution to the society. The influx of experienced and new talents from prospective employees who are unable to secure employment opportunities in the private sector provides a good addition to the operations of social enterprises as they bring new skills and expertise that would contribute to increasing the efficiency of such enterprises.

One significant advantage that these professionals enjoy by starting new social enterprises during times of recession is the relatively low capital needed to start such enterprises (compared to profit-making enterprises). This advantage only adds to the increased investor confidence that these entrepreneurs also enjoy. Even though a limited access to credit during recessions daunt the prospects of starting new enterprises during recessions, it is important to say that starting social enterprises during recessions is more promising than starting other types of ventures during the same period.

Positive Image

Understanding the public perception of a social enterprise is not a new area of study for researchers. Simon & Mayo (2010) argue that, “The associations of fairness and trust attached to a business being a social enterprise is high; compared with shareholder companies, social enterprises are viewed far more positively by the public” (Simon & Mayo 2010, p. 3). The positive image that social enterprises enjoy among the public is a key factor that contributed to their success (Worth 2012). Indeed, the mere fact that some people brand social enterprises as charitable organisations means that they may easily get a favourable public image. The positive image enjoyed by social enterprises partly explains why such enterprises continue to attract customers even during recessions. In other words, the fact that buying goods from a social enterprise advances a larger social cause of promoting the well-being of the community motivates many people. Therefore, humanitarian concerns, which override economic concerns, motivate many people to support social enterprises during recessions. The positive image that social enterprises enjoy also ensures they have committed partners that may support the organisation even during bad economic times. This positive image therefore ensures that the enterprises have a steady flow of funding throughout almost all economic times (Worth 2012). Similarly, such enterprises may enjoy free labour from volunteer organisations that may want to contribute to their activities. This public goodwill ensures that social enterprises enjoy significant discounts and contributions from highly qualified personnel. These advantages create a very attractive model of production where customers can get high quality services and products from social enterprises, at cheap costs. Social enterprises sustain this outcome because they are not motivated to make huge profits (Worth 2012).

The benefits of social branding on an organisation’s corporate image is however disputed by some researchers who believe that social branding contains both negative and positive ramifications (Worth 2012). For example, as explained in this paper, some businesses prefer to do business with social enterprises because they believe by doing so they contribute to charitable causes. Worth (2012) expresses some pessimism with this view, by saying that having a charitable drive does not necessarily mean that a social enterprise will attract new customers. He explains that some customers perceive social enterprises to have poor and inefficient services, thereby derailing their abilities to attract customers who may be attracted by such factors. For example, some businesses in the UK employ handicapped people as a social venture, but some people see the services and goods offered by the disabled to be poor quality and inefficient. A minority group of researchers however hold this view.

Comprehensively, Martin (2001) believes that social enterprises strive to survive in recessions by embracing social cohesion. Meyskens et al. (2010) have proposed that the resource-based framework and the resource dependency theory should explain the way social enterprises interact with other social factors in the society. Through these frameworks, the researchers proposed that an effective interaction between social enterprises and social factors promote the realisation of economic values (Meyskens et al. 2010). The main point that the researchers tried to put across is the fact that external factors have little effect on social enterprises because recessions do not necessarily affect the relationship between social enterprises and the society. The way social enterprises conduct themselves when interacting with social institutions therefore determines their success during recessions (Meyskens et al. 2010).

Methodology

Research Design

The research design for this paper hinges on the qualitative methodology as the main research approach. This study adopts this approach because of its ability to capture people’s experiences and explain the underlying factors that inform different social situations (Johnson & Christensen 2010). This paper also used a case study design alongside this qualitative methodology. In detail, this study used three social enterprises in the UK as case studies for this research. Since there are only a few organisations that have undergone a scrutiny on their resilience in the recession, this paper only selects case studies of organisations that are available in the Brookes University library. These firms came from different sectors of the economy so that we have a broader picture of the main issues that influence the resilience of these firms during economic crises. To have a workable sample of firms, this paper evaluated three social enterprise firms from UK – Co-operative bank, John Lewis Partnership, and Cafe Direct. The research question informed the main philosophy that this study used to guide the research paper. However, the research philosophy was mainly interpretive.

Data Collection

The main data source for this study was secondary resources. This dissertation used research sources that are available through the online library for Brookes University Library. As noted in this study, case studies formed a critical part of the research paper. This study sampled the social enterprises because they met a few acceptable criteria, including the generation of more than 25% of revenue from the trade of goods and services, the derivation of less than 75% of turnover from grants and donations. This paper also selected the chosen enterprises because of their commitment to support social and environmental aims, their commitment to limit the amount of money they pay to shareholders (to less than 50% of trading profits), and their commitment to reinvest surpluses to the business and community.

Validity of Findings

Since the research questions for the paper comprehensively cover the focus of study, this paper contains solid findings (O’Donnell 2004; Karnac 2008; Stewart & Kamins 1993). Therefore, the synthesis of the findings derived from this paper should be useful to researchers who may want to undertake further research on a similar topic. Since, there is a high expectation to have highly transparent information in this paper; there was little interference from biased views about the companies sampled. Through such an approach, the credibility of the research process was therefore high (Everard, Morris & Wilson 2004; Remenyi 1998; Brown & Remenyi 2004; Ketchen & Bergh 2004).

Data Analysis

This paper used the interpretive approach to analyse the hidden meanings behind the different facts touted in this paper. The interpretive approach was beneficial to this study because it helped to position the meaning of actions pursued by social enterprises at the centre of the research topic. Broadly, the interpretive approach provided a platform to generate observable outcomes by understanding the practices of social enterprises during the recession. This approach therefore formed the main framework for contrasting different pieces of information regarding different sub-topics proposed in this study (Remenyi et al. 1998).

Limitations of Study

The main limitation for this research is that it provides an indicative assessment of the factors that inform the resilience of social enterprises in the financial crisis, as opposed to a representative assessment of the same. This type of research is therefore suggestive or expressive about the factors that inform the resilience of social enterprises in overcoming the adverse effect of the financial crisis. Therefore, at most, the findings of this study illustrate the dynamics that surround the resilience of social enterprises in the financial crisis. The lack of interviews to back up the research findings also outlines another limitation for this study. In part, the failure to include interviews in the research stemmed from the lack of adequate access to individuals who are knowledgeable about the research topic. The failure to conduct interviews also had significant ramifications for ethical considerations as outlined below.

Ethical Considerations

The lack of interviews minimised the ethical considerations that would be associated with this paper. Since this research aimed to promote neutrality in the research process by avoiding biased sources of information, like press releases, the main ethical challenge was the formulation of a neutral and transparent research (Corey, Corey & Callanan 2007; Corey, Corey & Callanan 2011; Lo, O’Connell & National Research Council (U.S.) 2006).

Discussion

Cafe Direct

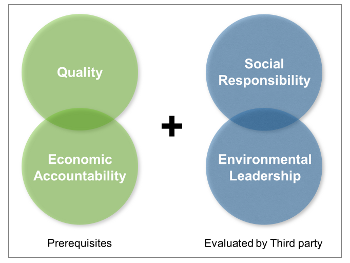

A group of philanthropic organisations (Oxfam and Traidcraft) started Café Direct (2009) as a social enterprise. The founders of the social enterprise started the organisation when global coffee prices were extremely high and exploitation of farmers and consumers was on the rise, globally. The vision of the founders was therefore to establish a fair-trade social enterprise that would counter some of these problems. Café Direct (2009) therefore became the first fair-trade drinks company in the UK with a strong ethical accreditation. The organisation has received this positive acclamation for being a leader in championing environmental concerns, human concerns, and animal concerns. The enterprise has especially championed these concerns by adhering to a strict ethical guideline for sourcing its raw materials. In detail, the enterprise adheres to the principles of ethical sourcing by ensuring that the practices involved in sourcing their raw materials are ethical. The diagram below represents a snapshot of the main pillars of the company’s ethical sourcing framework.

Quality and economic accountability outline the main prerequisites that inform the sourcing policy of the company. Later, the company ensures that they promote environmental leadership and social responsibility in the activities that they undertake, within and outside the organisation. To maintain high ethical standards, the company allows a third party to evaluate its social responsibility and environmental pillars, as described above.

Similar to most social enterprises that have nurtured long-lasting relationships with their trading partners, Café Direct (2009) enjoys respectful relationships with over 280,000 coffee and tea growers. The company also enjoys mutually beneficial relationships with close to 40 organisations that also engage in fair-trade business. These relationships span more than ten countries and affect close to 2,000,000 people around the world (Thorpe 2011).

Similar to other social enterprises sampled in this study, Café Direct (2009) invests most of its returns to promoting social initiatives in the community. For example, Thorpe (2011) says that in 2006, the social enterprise invested close to £13 million in welfare programs to benefit local communities and affiliate organisations that cater for the interests of its farmers. Comparatively, the company only invested about £4 million in sustaining the activities of the organisation (Thorpe 2011). Through this fund distribution, Café Direct (2009) channels most of its resources towards improving the welfare of the community and its partner organisations. This model is in tandem with the company’s mission, which strives to, “change lives and build communities through inspirational, sustainable business. We focus our social and economic impact in the developing world” (Café Direct 2009, p. 2).

Throughout the recession, Café Direct (2009) proved most of its critics wrong when they thought the financial crisis would severely affect the organisation. To their surprise, the company managed to increase its market share to about 35% (in 2007) (Thorpe 2011). Throughout the recession and the recovery period, the organisation has been able to maintain this market dominance and elevate its position of being the seventh largest brand of tea in Britain (Thorpe 2011). The enterprise also holds the fifth position among the largest coffee brands in Western Europe. The positive performance of the Café Direct (2009) traces to a research study conducted by (Thorpe 2011) which shows that most people continued to shop ethically throughout the recession. To expound on this finding, Café Direct (2009) said, “By an overwhelming majority, 77% are still shopping ethically, 21% do sometimes and only 2% have stopped shopping ethically in the downturn” (p. 1).

Part of the organisation’s success also stems from the findings of a study by IGD (cited in Thorpe 2011) which showed that, globally, there was an increasing appeal for companies that embraced fair-trade policies. Interestingly, Café Direct (2009) started adopting the fair-trade policy before the UK launched the fair trade mark. Since the enterprise was a leader in this regard, it used many resources and local mobilisation to convince people that they should buy their products. This success led the company’s executive director to say:

“We are now delighted to see our pioneering way of doing business has been a great example. In the past eight years, sales of Fair-trade have seen a 24x rise to £700 million in 2008, and it just seems to keep on growing” (Café Direct 2009, p. 5).

The resilience of Café Direct (2009) throughout the recession firmly stems from its ethical conduct, which has attracted many customers to its stores. The mere willingness of the organisation to give its producers a voice and to refrain from engaging in unfair trade policies inform why many customers keep trooping to the company, even when the recession hit hard. Similar to the way its customers remained loyal to the organisation, Café Direct (2009) also remained loyal to its producers by maintaining its share of investments to its partners. Thorpe (2011) says that the company invested more than half of its profits to support its partners even at the height of the crisis. The company also reaffirmed its commitment to its partners that it will sustain its support despite the economic condition of the time. Thorpe (2011) says, “This commitment also reflects the company’s holistic view of sustainability, which goes well beyond environmental issues to face its economic and social impact head on” (p. 10). For a long time, the company’s ethical conduct has informed many of its policies and strategies. Through the positive impact that the company has had on the community, it is therefore prudent to say that the key success factors for Café Direct (2009) has been its ethical philosophies that sustained its sales throughout the recession.

John Lewis

John Lewis partnership is a known social enterprise in the UK. The company has a significant presence in the retail and non-retail food market. In light of this market focus, John Lewis runs several departmental stores in the UK, including the John Lewis Department Stores and the Waitrose Supermarkets (among other stores in the country). Since the company is mainly owned by a group of employees (about 84,700), the company’s decisions are mainly informed by the opinions of the employees (also known as partners) (JLP 2013). A trust normally runs the affairs of the company.

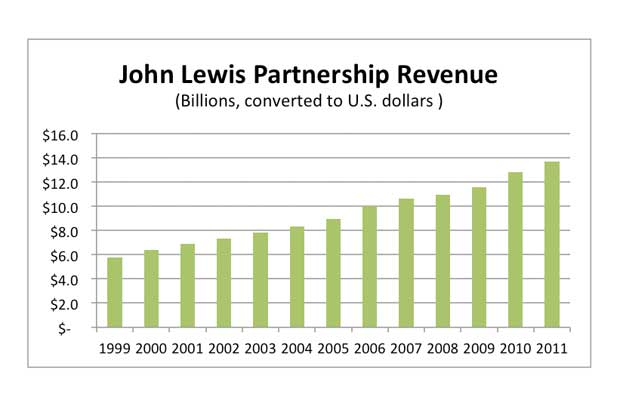

In terms of size, people consider John Lewis to be among the largest private companies in the UK, with an annual turnover that rivals among the most successful companies in the country (JLP 2013). Throughout the recession, John Lewis posted increased turnovers, and high profits, just like most other social enterprises sampled in this paper. For example, from 2007 to 2010 (at the height of the recession), John Lewis increased its annual turnover from £6.8 billion to £8.2 billion (JLP 2013). During the same period, its profit before tax increased from £379.8 million to £431 million. Still, at the height of the recession, the company’s partners received bonuses that averaged about 17% to 18% of their earnings (JLP 2013). The following table shows how John Lewis reported increased revenues for its partners, not only during the recession but for the past decade.

Analysts who have analysed the above financial records have commended the positive financial performance of John Lewis during the recession because the company managed to sustain its growth despite giving its members a strong control over the operations of the company and promoting fair compensation, even when the recession was still strong. Such financial reports show that the company registered significant growth in its bottom-line operations throughout the recession. Stated differently, the company has been extremely resilient throughout the recession. This performance arouses a lot of curiosity regarding the main factors that inform its success in the recession.

A careful scrutiny of the activities of John Lewis shows that much of the company’s success during the recession stems from the company’s strength in self-support. Many employees in the organisation agree with this sentiment by saying that the mutual dependence at the organisation is part of the key to understanding company’s success (JLP 2013). Certainly, one employee says, “The partnership was founded on the doctrine that mutual dependence is necessary to social wellbeing” (Nicholas 2011, p. 5). Mutualism is a great driving force behind the success of companies that share John Lewis’s business model as it fosters a sense of togetherness and shared responsibility (Nicholas 2011). The mutual ambassador at John Lewis Company says that “mutualism” is a key ingredient in understanding the company’s success after affirming that even though the concept does not automatically guarantee the company’s success, it has offered several advantages to the operations of the company (Nicholas 2011). Referring to the company’s success, one researcher who has extensively studied the success factors of John Lewis says, “What we have discovered at John Lewis is that co-ownership leads to increased levels of productivity, low absenteeism, low staff turnover, higher levels of commitment, and higher levels of well-being” (JLP 2013, p. 3). Also informing the company’s success is a high level of satisfaction that most employees of John Lewis enjoy. In fact, the company does not hesitate to say that its employees enjoy a higher level of well-being compared to other employees in similar organisations (JLP 2013, p. 3). For example, “mutualism” positively affects the productivity of front office staff members who think that they do not have the presence, or the power, to influence most of the decisions that affect how managers run the company. In other words, “mutualism” makes them realise that nobody is in a better position to know how the organisation could improve productivity at the front office (through either seeking solutions or sharing their experiences). The advantages of “mutualism” seem to be rubbing off on other social enterprises and entrepreneurs who are beginning to explore the advantages of “mutualism.”

The main issue that emerges here is the understanding the advantages and disadvantages of “mutualism.” One area where the mutual ambassador of John Lewis agrees to be beneficial for enterprises that embrace “mutualism” is the provision of solutions to some social and organisational problems (JLP 2013). However, he cautions that “mutualism” may not be very appropriate for some organisations that offer certain public services. For example, he says, “mutualism” is not necessarily appropriate for social enterprises that spend a lot of money on research and development because they have a higher risk of failure than ordinary organisations (JLP 2013). He also cautions social enterprises that require their employees to take high risks in their activities by saying, “mutualism” may be disadvantageous to their operations (JLP 2013). In the same breadth of analysis, Valerie (2001) cautions social enterprises that require a lot of capital to undertake infrastructure projects against adopting “mutualism” as an operational concept. The main reason advanced for this caution is the fact that, “Mutual enterprises secure their investment capital from profits or borrowing and in many models cannot distribute equity stakes” (JLP 2013, p. 4).

The main advantage that emerges here, despite the constraints of “mutualism,” is the fact that most of the capital invested through the “mutualism” concept tend to have a long-term (positive) impact on the organisation’s sustainability record. Indeed, when the limitations of “mutualism,” on short-term basis, are conceptualised, the advantages of the model begin to be more apparent for organisations. These advantages are very clear for organisations that adopt the mutualism concept. For example, JLP (2013) affirms that most organisations, which are employee-owned (like John Lewis), performed better than other companies during the recession because they positioned themselves to enjoy the opportunities created by “mutualism.” The mutual ambassador of the company affirms that, “At John Lewis, we have consciously increased our capital investment in the downturn, as others have been cutting theirs, because the opportunities are there” (JLP 2013, p. 4). Through the above analogy, in my view, it is almost inevitable to agree that “mutualism” forms a critical component of the company’s success.

In an unrelated context, the idea that a company’s staff can partly own the company also contributes to the success of John Lewis because there is an increased sense of commitment of the employees to work harder as they feel they own part of the company’s success. Having committed employees in the organisation especially works best in service organisations (Valerie 2001). The director of partnership services at John Lewis affirms this view by saying that service-centred organisations tend to enjoy a greater deal of success by adopting employee-owned models because the quality of service is usually proportional to the devotion of the company’s activities to their work (JLP 2013). Some people say that the success of such organisations firmly point towards self-interest, but the director of partnership services at John Lewis disagrees with this opinion by saying,

“Within John Lewis, for example, the employee owned model encourages us to employ partners who are motivated, committed, and passionate about the business. Each of us gets involved in the difficult decisions, and this is the anchor for much of our success” (JLP 2013, p. 5).

The “catch” in the above understanding is the need for all partners to demonstrate much commitment to the organisation’s activities, and at the same time demonstrating the patience to achieve their goals. Indeed, through the success of John Lewis, which has outlived many recessions (since its inception in the 1800s), there is little doubt regarding the belief that its success depends on the consistency of leadership, which informs its steady growth. The focus on long-term benefits is therefore vital to understand the company’s success and resilience throughout the recession, because as JLP (2013) says, “If the target is solely short term results, it is very hard to build the culture of shared ownership that then becomes the engine of future success” (p. 6). Since the seeds for long-term success exist in all the partners of the organisation, the partners are undeterred by short-term challenges, as they remain focused on building a strong mutual sector in the public service. The company also strives to build and maintain long-term relationships with their partners and customers because they believe this is the best way to secure support for the company, even when the economy is not performing well. This commitment to nurture long-term relationships has proved to be beneficial for the company, mostly because it has enabled it to remain relevant when there has been immense competition from other companies and social enterprises (Bennie 2013).

Encouragement and consistency are constant virtues that the founders of John Lewis inculcated among all the partners of the company because they inform the consistency of leadership in the organisation (Bennie 2013). Concerning this understanding, the director of partnership in the company says,

“I am convinced that if we promote encouragement and consistency, we will have many shining examples of independent organisations providing public services that provide both a market leading service and working experience and would sit comfortably against the best in any other country” (JLP 2013, p. 7).

The provision for employees to enjoy part-ownership of the company outlines the business model for John Lewis. This business model keeps employees more invested in the company’s activities. Increased investments in work activities improve the productivity and profits of the organisation. However, underscoring the deep employee commitment to the organisation is a more engrained sense of ethics and value adherence to promote social cohesion and social cohesion.

Many social enterprises today have a relatively new sense of ethos that defines their businesses, but John Lewis has been in the business for a long time and therefore, its ethical principles are more long-standing and deeper than most businesses. Moreover, because of the sheer size of the company’s operations, some people believe the company has a greater impact on the society than most organisations (JLP 2013). The fact that John Lewis has been in the market for a long time humbles the idea that social enterprising is a relatively new concept. The ideals of the company’s founders therefore manifest in most aspects of the company’s operations. Being a good corporate citizen is a notable ideal that the founders of the company have passed on through successive generations in the company. John Lewis has also thrived on promoting values that border on respect, honesty, and fairness, especially regarding the way it interacts with its partners and customers (JLP 2013). These values have enabled the company to earn the reputation of an employer with distinction, thereby enabling it to attract the best human capital, even when the economy has not been performing well. Therefore, unlike many profit-making businesses, John Lewis has gained the trust and respect of many investors because it acts with integrity and courtesy (Bennie 2013).

Co-operative Bank

Like John Lewis, Cooperative bank has posted increased growth throughout the recession period. Indeed, since 2009, the bank has increased its reputation as an economic powerhouse. In the same manner, the company has gained significant political support throughout the recession. Since the Co-operative bank is a member-owned bank and engaged in the business of social enterprising, the bank has committed its earnings to support community programs and initiatives (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). Over the years, the bank has strived to distinguish itself from other banks in the UK by proving to its stakeholders that its motivations do not focus on profit making, but social enterprising. One way that the bank has tried to prove to its stakeholders that it focuses on social enterprising is proving that its ethical policies are mainly customer-led. One initiative that has re-affirmed the company’s commitment to social responsibility is “join the revolution” program that the company has used to prove that its main purpose stretches beyond making a profit from its activities (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). Villeneuve-Smith (2011) says this program has encompassed the aspirations of the bank as a social enterprise. Through its commitment to remain true to its ethical branding philosophy, Cooperative bank has managed to increase its profile and post a positive financial performance throughout the financial crisis. For example, the International Labour Office (2013) says, “At The Co-operative Bank, we have seen a 79% increase in new customers, since 2009, in the wake of the banking crisis, as more and more consumers decide to do their banking with a trusted and ethical brand” (p. 3).

The international monetary fund has joined the group of independent researchers who support cooperative banks as the most stable financial institutions. A 2004 report by the international body sampled more than 16,000 banks in Europe and affirmed that cooperative banks were more stable than investor-owned banks (the report measured the stability of banks based on their ability to be insolvent) (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). The international body also argued that cooperative banks were more resilient during the financial crisis because they did not have a strong need to make profits for their shareholders when the market was not performing (Clara 2010). Therefore, they could use their surplus money as the first line of defence in an economic crisis. Indeed, unlike investor-owned banks, which are highly diversified and have an obligation to maximise their shareholder values, cooperative banks have the privilege of using their profits to build their reserves. The International Labour Office (2013) supports this view by saying, “Cooperative banks in normal times pass on most of their returns to customers, but are able to recoup that surplus in weaker periods” (p. 20). Comparatively, investor-owned banks have a strong need to please their shareholders by making profits, even when the market is not doing well. When the economic crisis hit hard, they were therefore more vulnerable to the crisis than the cooperative banks. The cooperative bank (UK) therefore entered the crisis with a relatively stronger capital base than most investor-owned banks in the country. Therefore, before and after the crisis, the cooperative bank managed to maintain its credit rating (at ‘A’ upwards) (Villeneuve-Smith 2011). This splendid performance was expected, considering the cooperative banking model does not necessarily obligate the bank to maximise its equity.