Abstract

Most management theories are based on certain ground rules about organizational structure. The importance of strategy in business cannot be overemphasized; an organization needs clear objectives, both in the short-term and long-term, to remain competitive. In this paper, the constructs and variables of Ansoff’s strategic management theory are analyzed. Also, the criteria for comparing and evaluating strategic management theories is given.

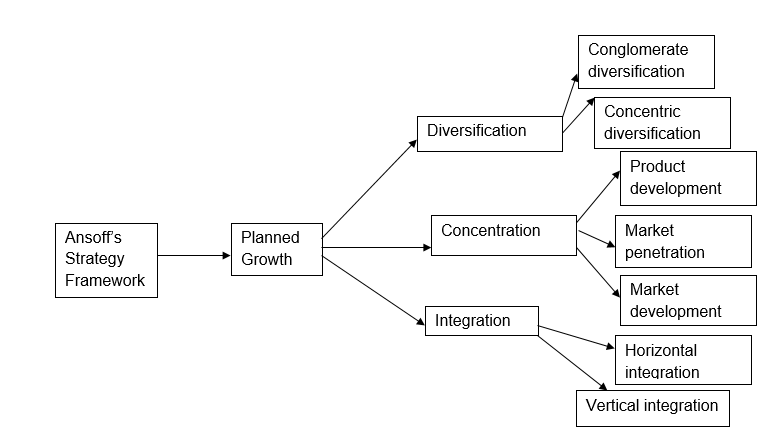

Many efforts have been put into identifying and defining the variables and constructs of the strategic management theory as well as the relationships between them. Ansoff proposes a matrix for defining strategy in an organization; it describes how concentration, integration and diversification fit together to give a strategic management framework that is specific to each organization. Ansoff’s theory meets the evaluation criteria (falsification and utility) adopted in this paper.

Introduction

Strategy is important in the modern business environment. Unlike general management, strategic management focuses on clear, strategic objectives that reflect long-term organizational goals (Bacharach, 1989). The concept of strategic planning was first developed by Igor Ansoff, a business manager who served both in the military and academia. The strategic military operations formed the underpinnings for this theory, which, in the business context, Ansoff called strategic management. Strategic management focuses on choices, purposes, performance and governance in the business, economic, political and social contexts (Buchanan & Bryman, 2009).

This paper critiques the elements of Ansoff’s framework/matrix on strategic management theory, its formulation and the efficacy of its application at the corporate level. It also provides the criteria for comparing and evaluating strategic management theories.

Putting the Theory in Context

Ansoff’s conceptual framework provides managers with an instrument for evaluating and exploiting the profit potential of an organization in a way that enhances an organization’s competitive advantage. It balances “external features of the product-market strategy and internal fit between strategy and business resources” (Ansoff, 1979). Ansoff’s framework allows the management to evaluate historical and current data in a way that facilitates the alignment of organizational goals with the external environment.

Often, managerial decisions do not reflect current market trends; instead, managers rely on historical data to make decisions. Ansoff, based on empirical data, proved that by combining both current and historical data and aligning organizational plans to match future and present business environments, top managers can develop a method for optimizing a firm’s future success (Popper, 1999).

Thus, based on Ansoff’s approach, top managers formulate plans that are passed down the corporate ladder for implementation. The building of future scenarios based on environmental indicators and the planning for future discontinuous environments underpin the Ansoff’s approach. Ansoff is credited for his contribution to the concept of synergy in strategic planning (Snow & Thomas, 1994). His work adds to the growing body of literature by providing a prescriptive, multidisciplinary approach for managing change process within an organization.

Evaluation Criteria

No theory can be termed recommended for application in organizations unless it has criterion for its evaluation. Whetten (1989) identifies two criteria for theory evaluation:

- utility and

- falsifiability.

Utility is defined as the usefulness of the framework while falsifiability refers to empirical validation of the theory systems. With an understanding of the variables of a theory, the two criteria can be applied to Ansoff’s strategic management theory.

The constructs, variables and their relationships must show clear relationships and concept development (Krosnick, 1999). On the other hand, a falsifiable theory must the variables must be coherent and reliable. This requires the theorist to time and place the constructs were measured. Falsefiability can also be evaluated based on empirical adequacy (Miner, 1984). This simply means that the hypotheses must be set in a way that makes them subject to rejection or disconfirmation. This paper uses falsefiability and utility criteria to evaluate Ansofff’s strategic management theory.

The Theorist’s Methodology

Ansoff’s strategic paradigm derives from Chandler’s (1962) framework, which proposed a dynamic association between an organization’s strategy, the environment and the internal changes taking place within an organization. Chandler’s paradigm combined six management concepts. These included; the systems theory (organizational culture, values); sociotechnical systems (technical capacity); microeconomic theory (capital budgeting, survival); individual behavior (risk aversion, individual aspirations); strategic planning; and decision-making (organizational change, duties and responsibilities) (Behling, 1978).

Based on these concepts, Ansoff (1979) identified “strategic budgeting, urgency, change type, change frequency and predictability” (p. 62) as the key variables for his theory. He postulated that effective strategic behavior requires a dynamic balance between technological ability and organizational culture. Here, Ansoff postulated a clear relationship between the constructs of his theory.

Ansoff used peer-reviewed primary studies to generate three key constructs for his framework: diversification, concentration and integration. Based on the falsefiability criterion, Ansoff enhanced the credibility of his paradigm by illustrating the relationship between these three constructs. He also identified the specific variables and relates them to the constructs. On the other hand, the time and place or organization where he measured these variables is not provided.

Three assumptions underlie Ansoff’s theory on strategic management; consistency, predetermined purpose and rationality (Denyer & Transfield, 2009). Ansoff made the assumption that the outcomes of strategic planning are consistent across all sectors including military and political spheres. Also, the assumption of rationality overlooked basic elements of management behavior; tradition and intuition (Fisher, 2011).

These elements shape the business values within an organization and should be included in the strategic planning process. Using Ansoff’s theory and the Optimal Strategic Performance Position (OSSP) tool, managers of small and medium enterprises can ascertain the organization’s capability and optimize business performance. This implies that Ansoff’s theory meets the criterion of utility.

Support for the Theory

Ansoff’s theory was criticized by Mintzberg who argued that Ansoff’s methodology is not scientific and as such, his research is not prescriptive (Mintzberg, 1990). Mintzberg implied that Ansoff’s methodology is descriptive. Mintzberg also argued that Ansoff’s sources were not valid or reliable and therefore could not meet the premises of a prescriptive model. Nevertheless, his attempt to discredit Ansoff’s concepts was not successful as Ansoff’s framework can adapt over time and thus a valid strategic management theory.

Strategy makers acquire strategic decision-making skills without the use of intuition (Bartunek, Rynes & Ireland, 2006); they focus on the strategy making process rather than the outcomes. This view is consistent with Ansoff’s theory, which overlooked the role of intuition in strategy formulation. Also, in most organizations, strategy formulation process entails preparation of programs and plans by top executives, and implemented by the employees (Daft, 1983). Strategies are implemented according to set goals, programs and budgets derived from market analysis. This approach is consistent with Ansoff’s characteristic of strategic management that encompasses a strategic budget for an organization.

Credibility of Ansoff’s Theory

Ansoff’s matrix provides a model for determining opportunities for expansion of a firm in the modern business environment. The matrix provides some of the strategies an organization can use to expand its business. These include diversification, penetration into existing markets, expansion into new markets and product development (Ansoff, 1979).

Based on the Ansoff’s matrix, the aspects of product differentiation and market development are considered. This forms part of the strategic decisions of most companies and thus, the strategic management theory meets the criterion of utility. With regard to differentiation, a common strategic option for most firms is to offer products that meet customer needs (Campion, 1993). The theory built on Chandler’s (1962) framework for strategic planning. However, Ansoff added two elements that are important in the development of the strategic management discourse. He postulated a synergy between internal and external environment as represented in the matrix by the market and product dimensions.

Ansoff identified four strategies; market penetration, which focuses on expanding a firm’s market to reach new clients; market development, which involves the introduction of new brands into the market; product development, where the firm provides more products to existing clients; and diversification, where the firm introduces new products into the market. The concept of strategy is largely unclear and does not support concrete actions by the management of a firm (Behling, 1980). In light of this, Ansoff framework offers strategies that can support strategic decision-making for firms across different sectors. Ansoff borrows from an earlier theory by Chandler (1962) that combined various elements of management to develop a framework for strategic planning.

The Researcher’s Credentials

Igor Ansoff was a business manager who worked in academia and in the US Navy. Professionally, Ansoff trained as a mathematician and began his career as consultant at the RAND Corporation before moving to Lockheed Ltd. At Lockheed, Ansoff ascended to the position of a vice president (Hitt, Gimeno & Hoskisson, 1998). Ansoff’s experience at Lockheed influenced his theory of strategic management.

As a vice president at Lockheed, Ansoff witnessed market turbulence of the 1970s in the American industry. It was his experience in managing Lockheed through the turbulent times that elicited his interest in strategic management in his later works (Scandura & Williams, 2000). His theory of strategic management reflects his experiences at Lockheed Corporation. It is clear that Ansoff’s market dimension borrows significantly from his experiences during the turbulent market.

Conclusion

It would be imprudent to assume that any strategic management theory can be applied in organizational settings. Insights and methodologies of some theorists may not apply to a particular situation. As such, theories must be evaluated and tested empirically to provide a basis for prediction. The criteria, falsification and utility, can help to demystify the theoretical underpinnings of Ansoff’s theory and determine its appropriateness in the modern business environment. The evaluation shows that Ansoff’s framework meets both criteria but does not clearly identify the sources of the constructs and variables.

References

Ansoff, I. (1979). Strategic management. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Bacharach, S. (1989). Organizational theories: Some criteria for evaluation. Academy of Management Review, 14(9), 496-515.

Bartunek, J. M., Rynes, S. L., & Ireland, R. D. (2006). What makes interesting research and why does it matter? Academy of Management Journal, 49(1), 9–15.

Behling, O. (1978). Some problems in the philosophy of science of organizations. Academy of Management Review, 3(7) 193-201.

Behling, O. (1980). The case for the natural science model for research in organizational behavior and organization theory. Academy of Management Review, 7(1), 483-491

Buchanan, D., & Bryman, A. (2009). The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Campbell, J. P. (1990). The role of theory in industrial and organizational psychology. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Campion, M.A. (1993). Article review checklist: A criterion checklist for reviewing research articles in applied psychology, Personnel Psychology, 46(3), 705-718.

Daft, R.L. (1983). Learning the craft of organizational research, Academy of Management Review, 8(7), 539-546.

Denyer, D., & Transfield, D. (2009). Producing a Systematic Reviews. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Fisher, A. (2011). Critical Thinking, An Introduction. London : Cambridge University Press.

Hitt, G., Gimeno, A., & Hoskisson, S. (1998). Current and future research methods in strategic management. Organizational Research Methods, 1(6), 43-44.

Krosnick, J.A. (1999). Survey research, Annual Review of Psychology, 50(1), 537-567.

Miner, J. (1984). The validity and usefulness of theories in an emerging organizational science. The Academy of Management Review, 9(3), 296-306.

Mintzberg, H. (1990). The Design School: Reconsidering the Basic Premises of Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 11(6), 171-195.

Popper, K. (1999). The logic of scientific discovery. London: Routledge Classics.

Scandura, T. A. & Williams, E. A. (2000). Research Methodology in Management: Current practices, trends, and implications for future research. Academy of Management Journal, 43(6), 248-264.

Snow, C.C. & Thomas, J.B. (1994). Field research methods in strategic management: Contributions to theory building and testing. Journal of Management Studies, 31(4), 457-480.

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 490-495