Introduction

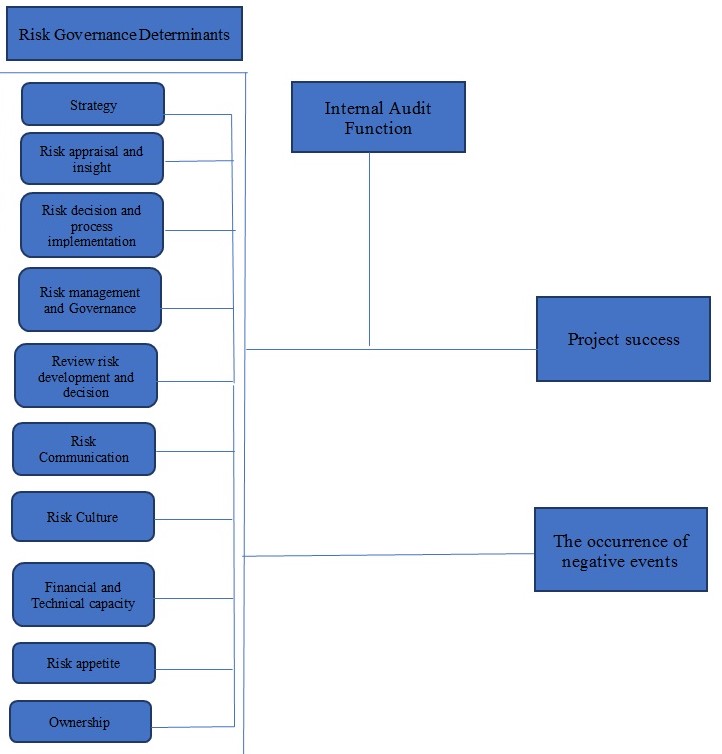

Research aim: The aim of the research is to determine and assess the most important risk governance determinants that contribute to the project success.

Objectives of the research:

- To review the existing risk governance frameworks and develop/adopt relevant risk governance framework for Dubai public sector context.

- To review and extract the most risk governance determinants.

- To seek opinion of Auditors and Risk Managers on the importance of the extracted risk governance determinants.

- To use statistical methods to determine the importance of risk governance determinants and to confirm the association between risk governance and project success.

Research questions:

- What are the existing determinants of risks governance in public sector?

- What are determinants of project success?

- What are the audit function task in managing the risks in the public organisations?

- What is the association between risk governance and project success?

Research hypotheses:

There is no significant difference in rating the importance of the determinants of risk governance:

- Determinants of risk governance are positively related to projects success

- Determinants of risk governance are negatively related to occurrence of negative events of projects

The relationship between the determinants of risk governance and project success are moderated by the Internal Audit Function.

Literature review I: Risk Governance

Introduction

This chapter critically reviews existing literature in the area of risk governance and related frameworks in the private and public sectors. It presents various views and perspectives on risk governance definitions and frameworks, culminating in the development of a maturity model for risk governance in public investment projects. It concludes with a summary of the main issues and research gaps identified from the literature and the emerging research questions that will guide the present research.

Risk has invariably existed in society for a long time; however, its growing complexity has led to the evolution of risk management strategies to control its effects. The capacity to understand the development of risk and manage risk is a critical ingredient for the success of organizations and society. In recent years, the government’s role and efforts in risk regulation and management have intensified. Public sector organizations manage and control risks at multiple integrated levels through policy, legislation, regulatory tools/regimes, feedback loops, and rules (van Asselt & Renn 2011). The different levels represent dynamic subsystems in the public sector that provide interfaces for interaction between the public and state actors. Therefore, effective management of risks relies on the interactions, learning processes, and communication among the various stakeholders acting at the federal or local level.

Risk can be difficult to frame in definitive terms. Its definition is marked by a diversity of perspectives and principles for its detection, evaluation, and management (van Asselt & Renn 2011). In spite of the diverse definitions, the risk remains a key consideration in public and public-sector projects. van Asselt and Renn (2011) distinguish between simple and systemic risk. While simple risks have clear causes or effects and involve minimal uncertainty levels, systemic risks are complex and are shrouded in uncertainty/ambiguity. In fact, one of the risk definitions often used is the one given by the International Organisation for Standardisation, i.e., the risk is “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” (ISO 2015, p. 13).

Therefore, uncertainty is a key component of risk. Uncertainty often results from complexity. The complex social issues and multiplicity of stakeholders in the public-sector context increase uncertainty. The concept of uncertainty means that risk does not conform to the known principles of causation. Firm-specific uncertainties may be related to R&D, employee/managerial behavior (strikes), or operations – labor and input supply (Hopkin 2012). In the public sector, uncertainty may come from state policies related to expropriation and nationalization as well as conflicting stakeholder values and interests. Social and economic policies can also increase uncertainty and risk levels in a country.

The introduction of the concept of risk governance in organizations was meant to support structures for predicting and managing systemic risks that are characterized by high-level complexity, ambiguity, and uncertainty. In the private and public sectors, a myriad of regulatory, social, and organizational pressures influences risks. Risk governance frameworks give a blueprint on how to identify, assess, and manage risks to realize organizational objectives. This literature review involves a synthesis of the existing risk governance frameworks in a bid to develop a maturity model applicable to public sector organizations or projects. It begins with a review of risk and uncertainty definition followed by risk governance definitions and a descriptive analysis of various frameworks. A summative assessment of the main issues and research gaps identified from the literature is provided in the summary section.

Risk and Uncertainty and project risk managment

Theorists have attempted to define risk and to develop working models for risk management since the 1950s (Prpic, 2016). Economist Frank Knight, the founder of the Chicago School is often credited with this effort (Besner & Hobbs, 2012).

However, defining risk and what it really entails has been a challenging task. For example, Holton (2010) points out that risk theorists such as Knight and Markowitz have not provided a clear definition of risk, and this ambiguity has continued since the 1950s. Besner and Hobbs (2012) for example, point out that Knight considered a risk to be an event that could have an impact that can be quantified and measured, whereas uncertainty itself is the source of the risk, reflecting an objective interpretation of risk. On the other hand, Holton (2010) argues that Markowitz focused on the subjective aspect of interpreting risk by basing it on the judgment of decision-makers in assessing the likelihood of risk and the resulting variation in expected outcomes.

Alternatively, Sciotte and Bougault (2008) define risk as an identifiable event with negative consequences, while Hubbard (2009) defines it as the chance of an unfortunate event multiplied by the cost that results if such an event occurred, which effectively means that risk is equivalent to the expected loss arising from an event, but such a definition is clearly focused on the financial cost of the outcomes that arise in the event that the risk materializes.

The risk may also be defined as the chance of the occurrence of an uncertain event that is associated with outcomes that could be either positive or negative (Reding, 2013). Traditionally, the risk was limited to negative outcomes whereas positive outcomes or opportunities were not treated within the context of risk management (Ward & Champan, 2013).

Although risk assessment is often biased toward negative outcomes, the fact is that events with negative outcomes can impose a loss on a project and events with positive outcomes, if missed, can also result in lost opportunities (Wieczorerk-Kosmala, 2014). Additionally, the perception and measurement of risk are often based on perceptions and some degree of judgment, which makes it subjective, but it may also be quantified in objective ways (Simona-Iulia, 2014).

Dealing with risk is inevitable in any project, regardless of its size, and any attempt to manage risks requires understanding how risks are perceived and measured before they can be controlled or mitigated (Aaron, Clemons & Reddi, 2005). Hence, regardless of the context or the nature of a project or its size, risk management is a process that involves the identification, assessment, evaluation, and mitigation, and/or prevention of risks (Mazareanu, 2011).

Moreover, although it is not unusual for certain risks to receive more attention than others, it is generally agreed that risk management should be based on a holistic approach, a complex approach that involves understanding the interrelatedness between risks and their various impacts, but so far, the majority of approaches have focused on identifying risks separately and addressing their outcomes individually (Wu & Seco, 2009).

A project is often a complex undertaking that involves multiple stakeholders, numerous interrelated and unrelated processes, and different goals and objectives. It also requires the use of various inputs in these processes to accomplish a set of desired goals and objectives within a specific period of time (Hartono et.al., 2014). A project may also be defined as “a clear-cut investment activity with an explicit purpose and distinct beginning, duration, and end” (Charette, 1996, pp.112-113). The EC also defines a project as “a group of activities that must be realized in a logical sequence, in order to achieve a set of pre-established objectives, formulated by the client” (Zecheru, 2013, p.450). From economic and financial perspectives, moreover, Charette (1996) argues that a project in the course of doing business that involves the lowest opportunity cost and the most efficient way to achieve organizational goals and benefits while utilizing scarce resources.

In the context of project management, a project risk may be defined as any factor that affects the normal progress of the project or its feasibility (Teller, Kock & Gemunden, 2014). Likewise, a project risk may be defined as any predictable factor that may affect the project at any of its different stages of development (Sarker, 2013), and whether positively or negatively (Carvalho & Junior, 2013). Other definitions by project management associations define risk as “an uncertain event or act of circumstances which, should it occur, will have an effect on the achievement of objectives” or “a combination of the probability or frequency of occurrence of a defined threat or opportunity and the magnitude of the consequences of the occurrence” (Hubbard, 2009, pp.89-90).

Even in the simplest and smallest projects, controlling risks is often a complex task given the interrelatedness of inputs, processes, and outputs, whereas, in much larger projects, the prediction of risk is extremely complex to the point that it may be as reliable as “fortune-telling” (Charette, 1996, p.111). Accordingly, controlling project risks is in itself a complex process that requires robust management procedures (Gheroghe, 2012). These procedures fall under the concept of project risk management, that is, the process of identifying, evaluating, and analyzing risks, in addition to formulating measures that aim at mitigating and controlling risks surrounding a project. The process of risk management is not only limited to the design phase, but it is also required while the project is in progress and where it may face numerous uncertainties related to time limits and deadlines, financial shortages, and many other factors (Arias & Stern, 2011).

Another model for risk management that is relevant to project management is the Enterprise Risk Management Model which involves identifying risks, identifying causes, identifying controls, predicting likelihood and the magnitude of consequences, setting quantifiable ratings for each risk, making decisions to avoid or mitigate risks, and finally monitoring and reviewing execution to ensure that risk remains under control (Nocco & Stulz, 2006).

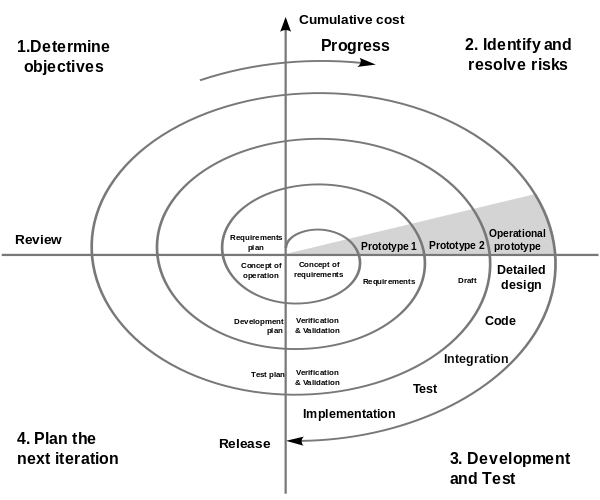

Boehm (1988) also proposed a risk management model for extremely large and complex software projects for government and defense industries. The model constitutes of four stages; determining project objectives and constraints; identifying risks, evaluating alternative courses of action, and resolving risk by taking the necessary decisions; implementing and verifying completion of steps with risk under control; and finally determining if risks remain at an acceptable level before proceeding to the next decision stage (Figure 1).

In implementing project risk management, managers have a variety of options to resort to in addressing potential risks. These may include risk mitigation decisions which involve either the reduction and/or elimination of risk; risk retention decisions which involve accepting the risk if the cost of its impact is tolerable or if the cost of retention or prevention is too high; risk transfer which involves the transfer of risk to other parties; and risk allocation which involves distributing the risk, possibly by sharing it with other partners such as entering into a joint venture (Berk, 2012).

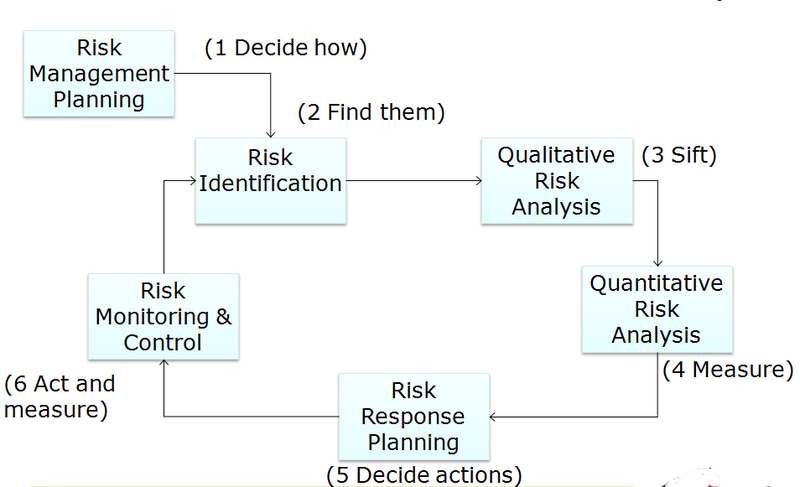

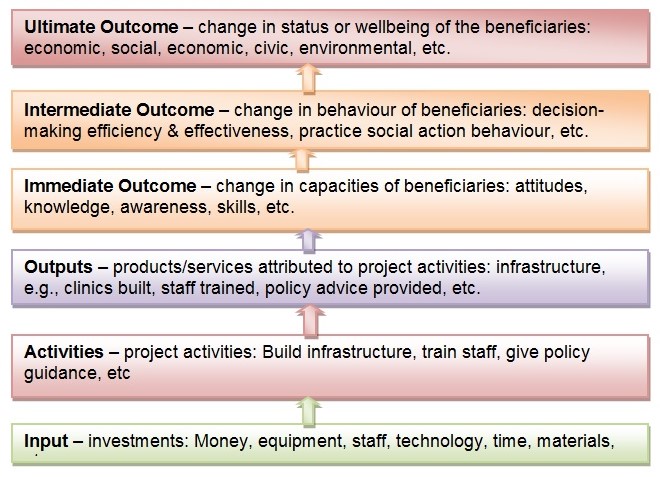

The concept of project risk management, therefore, is about developing a framework that entails measures to mitigate and/or prevent any possible threats that may obstruct project progress (Podean, Benta & Mirceana, 2010). Progressive definitions, however, perceive project risk management as the framework that provides management with the ability to avoid or mitigate negative risks and to take advantage of positive risks (Thamhain (2013). This concept is expressed in the standard project risk management process illustrated in Figure 2 (Prpic, 2016).

Project risk management has attracted significant attention from risk management scholars. However, with the growing complexity of projects, scholars have also increasingly paid attention to specific types of risk, especially those with substantial or detrimental impacts on projects (Powell, 2010). In the context of the massively growing size of projects all over the world and also in light of the global financial crisis, financial risk has specifically attracted unprecedented attention (Kerzner, 2013).

Governance and Risk Governance Definitions

The Standards of IIA define governance as “the combination of processes and structures implemented by the board to inform, direct, manage, and monitor the activities of the organization toward the achievement of its objectives.” (IIA, 2011)

OECD has introduced another definition which is “Corporate governance involves a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders. Corporate governance provides the structure through which the objectives of the company are set and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performances are determined.”(OECD, 2004) while OCEG defines governance as: “Governance is the culture, values, mission, structure, and layers of policies, processes, and measures by which organizations are directed and controlled. Governance, in this context, includes but is not limited to the activities of the board, for governance bodies at various levels throughout the organization also play a critical role. The tone that is set, followed, and communicated at the top is critical to success.”

A risk, in general terms, connotes the uncertainty or unexpected ‘adverse’ outcome of a situation or activity. The scholarly literature on risk governance explains the processes and frameworks for managing risks based on diverse definitions of risk governance. Klinke and Renn (2012) define risk governance as a comprehensive risk-handling process for addressing the “complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity” aspects of risk (p. 274). It entails an evaluation of the totality of regulations, processes, and systems involved in the risk data collection, analysis, and risk-based decision-making. Therefore, it extends beyond the traditional risk analysis to include normative principles on how public and private actors can manage risks.

Renn, Klinke, and van Asselt’s (2011) definition of risk governance follows a technocratic approach. They define it as the organizational structure and policymaking process that guide or control the regulation or mitigation of risks at the group, societal, national, or global level (Renn, Klinke & van Asselt 2011). This definition is based on the shift from centralized decision-making to multi-level public administration that characterizes modern governments. In another article, van Asselt and Renn (2011), extending on the International Risk Governance Council’s [IRGC] definition, describe risk governance as the application of core principles/concepts of governance in risk-based decision-making extending beyond formal (probabilistic and regulatory models) to include informal processes. The definition is informed by the inadequacies of risk probability models in managing public risks. It includes formal and informal systems for dealing with complex, uncertain, and ambiguous risks. In this article, the concept of governance primarily relates to policy development by government actors. However, since various stakeholders are involved in the management of society, including non-governmental organizations and the private sector, the definition has been expanded to include a diversity of actors/roles.

The phrase risk governance is utilized in a prescriptive and a descriptive context. Decisions about risks involve diverse players, regulations, political systems, and organizational structures – aspects pertaining to governance. Risk decisions are the outcome of the interaction between many players. From a governance perspective, the societal factors that precipitate outcomes characterized as risks need to be analyzed for effective mitigation. For Flemig, Osborne, and Kinder (2015), risk governance is both a normative and prescriptive process. They define it as a hybrid of “an analytical frame and a normative model” that guides risk decisions (Flemig, Osborne & Kinder 2015, p. 16). This decision-based risk governance differs from the technocratic approach in the sense that it assigns the decision-making role entirely to politicians.

Brown and Osborne’s (2013) definition of risk governance follows a different approach. They define risk governance as transparent engagement with the “nature, perceptions, and contested benefits of a risk” in complex situations (Brown & Osborne 2013, p. 199). This means that all relevant stakeholders in the public service are involved in the decision-making process. This transparent approach has been adopted in the modern public sector to enhance accountability. In addition to the inclusive decision-making process, the risk environment is characterized by regulations and best practices to enhance accountability in the public sector. Therefore, Brown and Osborne’s (2013) definition fits within the transparent risk management approach adopted in democratic systems.

Clearly, an appropriate conceptualization of the concept of risk governance should encompass a global view of risks that emerge in public investment projects. It should go beyond the traditional concepts of risk management or analysis to include decision-making processes related to a particular project. In this regard, Brown and Osborne’s (2013) definition fits well within this description, as it points to decision-making processes in a complex environment, such as the public sector. From a descriptive perspective, an appropriate definition must capture the totality of stakeholders, standards, procedures, and processes involved in making risk decisions. Considering the fact that risk governance goes beyond simple descriptive management of public risks, a satisfactory definition should include the normative elements or rules on how to manage risks in the public sector. It should involve all actors working in a transparent decision-making process. The adopted definition for this paper is that of Brown and Osborne (2013) who define risk governance as genuine engagement with the “nature, perceptions, and contested benefits of a risk” in complex situations (p. 199). The authors point out that this definition fits well with the characteristics of the public-sector risks, i.e., complexity, ambiguity, and uncertainty.

Risk Governance Frameworks

Various epistemological premises and ideas contributed to the development of risk governance as a concept. While the positivistic/realist view relies on the assumption that risk is assessed based on some ‘real’ standard, while the social constructivist approach considers risk a “social process”, not as a distinct entity (Renn 2011, p. 71). These ideas helped advance the principles and frameworks for managing contemporary risks. The conceptual use of the term ‘risk governance’ emerged in recent literature exploring policy development in the public/private sectors (van Asselt & Renn 2011). It is used within the context of public/private governance or development that has roots in the political science field. In this context, ‘governance’ stresses the role of non-state actors in the management and organization of societal issues (van Asselt & Renn 2011). This approach challenges the classical policy perspectives that followed a hierarchical power model centered on the government.

In the governance view, collective binding decisions are produced in “complex multi-actor networks and processes” (Jonsson 2011, p. 126). This means that multiple social actors are involved in governance. Besides the state, the other social actors include nongovernmental organizations, private institutions, expert groups, etc. In this regard, the power/capacity to organize and manage society is shared among the different actors. Governance can be considered a descriptive and prescriptive term. The descriptive sense of governance relates to the complex interplays between various social actors, structures, and processes (Jonsson 2011). In contrast, the prescriptive definition relates to the model/framework for the management of societal issues. The normative use of governance emphasizes transparency, involvement, and accountability.

The normative-descriptive ideas also apply to risk governance. The word ‘governance’ is utilized in “a normative and descriptive sense” (van Asselt & Renn 2011). The argument here is that while the regulation/management of simple or systemic risk problems follows the governance framework, risk decisions emanate from interactions between stakeholder groups. The ‘governance’ view gives a framework for examining and describing the factors precipitating risks. However, the unpredictable nature of risks calls for multi-stakeholder collaboration to adequately address and manage them. In the collaborative frameworks, new risk management principles and approaches are proposed in line with the prescriptive/normative perspective (Renn 2011). Therefore, risk governance is a blend of an analytical framework and prescriptive exemplars.

The usage of the term ‘risk governance’ has its roots in the lessons learned from the TRUST NET undertaking, which developed a model that included collaborative processes in decision-making (Renn 2011). TRUSTNET was a European Union interdisciplinary network established to develop the criteria for determining best practices in the governance of hazards. It comprised 80 experts drawn from regulatory agencies in industrial and medical fields across Europe. The network developed the concept of risk governance and the first model. Later, this notion was used in literature as an alternative paradigm to the traditional concepts of risk analysis and management by advocating for multi-stakeholder roles, processes, and systems (van Asselt & Renn 2011). However, risk governance was originally used to mean an all-encompassing system of “risk identification, assessment, management, and communication” (van Asselt & Renn 2011, p. 433). This view is consistent with the IRGC’s definition of the notion of risk governance. The IRGC (2015) incorporates the governance principles of “transparency, effectiveness, accountability, equity, and fairness” into its definition of governance framework (p. 12). The aim is to create effective collective actions to mitigate the effects of emerging risks.

The purpose of sound risk governance is to reduce the unequal risk distribution between different public/private institutions or social groups through multi-actor processes. A risk governance practice also creates consistent and uniform approaches for similar risk assessment and management (Renn 2011). Unlike the traditional approach of risk analysis that focused on high-profile risks, risk governance gives adequate consideration of high-probability risks irrespective of their profiles. It also involves risk trade-offs through effective regulations and policies. The approach also takes into account public perceptions, resulting in high public trust in the system.

Brown and Osborn’s (2013) Framework

The risk governance frameworks provide an approach for the analysis and management of risks within the public service or the private sector. Brown and Osborne (2013) suggest a risk governance model for managing risks related to innovation in the public sector. The framework links three management approaches and three innovation types (Figure 1). The first type is evolutionary innovation, whereby institutions utilize new “skills or capacities” to meet specific user needs (Bernado 2016, p. 14). The second type is expansionary innovation, whereby the current skills/capabilities are used to meet expanding user needs. The last one is total innovation, in which new capabilities/skills are developed to address new user needs (Brown & Osborne 2013). The authors offer three risk governance approaches, namely, technocratic, decisionism, and transparent methodologies. The technocratic model is only applicable in evolutionary innovation. In contrast, the decisionism model provides a framework for evolutionary and expansionary innovation. The transparent risk governance model can accommodate all the three types of innovation.

Figure 1: Risk Governance Framework for Public Service Innovation

The IRGC’s Framework

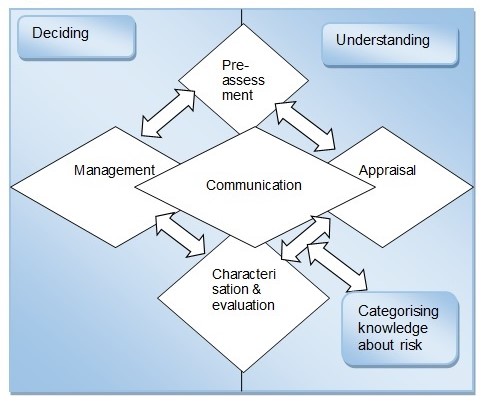

Another risk governance framework is the IRGC’s model that consists of five related phases. The phases include pre-assessment, appraisal, characterization and evaluation, management, and communication (Figure 2).

The model separates risk analysis from the understanding of risks. Risk appraisal is essential in understanding the nature of risks. In contrast, the implementation of risk decisions requires risk management. The framework begins with pre-assessment, whereby the risk is defined to facilitate its appraisal. The pre-assessment phase involves a set of questions that give the baseline data for risk assessment and mitigation.

More importantly, it reveals the factors that precipitate the risk and the associated opportunities (Bernado 2016). It also brings out the risk indicators and patterns that help inform the risk management approach. The governance shortfalls that occur during this phase include failure to detect risk signals, perceive their scope, and frame it appropriately.

The risk appraisal phase is where facts and assumptions are developed to make a determination if a situation portends a risk and how it should be handled. The appraisal involves scientific approaches, including estimating the probability of occurrence, and risk-benefit analysis based on stakeholder concerns (Bernado 2016). The process ensures that policymakers consider stakeholder concerns and interests when making decisions.

The next phase – characterization and evaluation – involves the consideration of societal values in decisions related to the acceptability or tolerability of the risk. At this stage, risk mitigation measures are identified for risks considered acceptable or tolerable (van Asselt & Renn 2011). However, if the risk is intolerable, the initiative is halted. The failure to address the issue of inclusivity, transparency, and societal values/needs, and timeframes precipitates risk governance problems.

The fourth phase is risk management. It entails the development and adoption of strategies or activities that help mitigate, avoid, or tolerate the identified risk. In this stage, multiple options are developed and the best one is selected for implementation. The risk management process entails the “generation, evaluation, and selection” of the best risk mitigation strategy (van Asselt & Renn 2011, p. 445).

It also entails evaluating the potential impacts of the selected risk mitigation option. The final phase of the IRGC framework is the communication of the risk management decision. Effective communication helps create awareness among stakeholders. It also enables them to understand the stakeholder role in risk governance (van Asselt & Renn 2011). The communication should inform the stakeholders/actors about their specific roles in managing the risk.

The IRGC’s framework has been adopted across multiple industries. In this model, an iterative process of communication cuts across the four phases. The IRGC framework is criticized for being one-dimensional. The model depicts risk governance as an additive process with distinct phases. However, researchers argue that the process is rather iterative, with steps like risk assessment and management not clearly delineated (Flemig, Osborne & Kinder 2015). Moreover, since various actors interact and influence each other, risk governance cannot follow a logical sequence.

In the IRGC framework, risk communication remains the unifying factor of the five phases of the model. The IRGC expanded the new framework by introducing deliberation and engagement, suggesting a bipartisan process between the actors. Another significant aspect of the revised model is the emphasis on institutional capacity and resources. The organizational resources/capacities considered in the new model include finances, social capital, human resources, and technological capabilities (Flemig, Osborne & Kinder 2015). It also includes the consideration of the actor-network, political and regulatory culture, and the social climate.

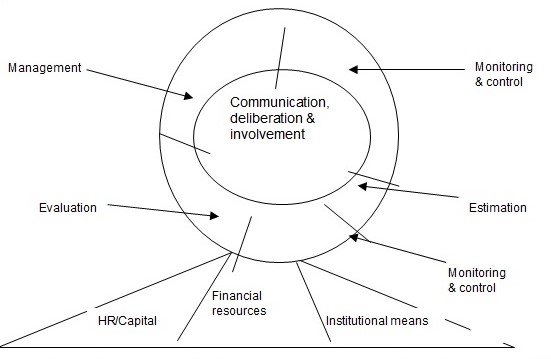

The Modified IRGC Framework

Renn, Klinke, and van Asselt (2011) propose a modified IRGC framework that includes the normative and descriptive aspects of risk governance. The proposed model comprises five stages, i.e., “pre-estimation, interdisciplinary risk estimation, risk characterization, risk evaluation, and risk management” (p. 237). The modified framework is illustrated in Figure 3 below. The pre-estimation stage involves the testing of multiple problems as possible risks. It entails an exploration of societal/community and political agencies and the public to identify factors ‘framed’ as risks. The screening also explores the culturally constructed risk candidates. Therefore, the pre-estimation stage is a multi-stakeholder process that brings together government agencies, industry actors, consumers, and various interest groups.

The second stage, risk estimation, entails the scientific evaluation of risks through risk assessment and concern (societal issues) assessment (Renn 2011). Various approaches can be used in risk estimation. Examples include the probability of occurrence, the extent of damage, ubiquity, reversibility, etc. The third step, risk evaluation, involves the quantification of the societal effects of risk and its probability of occurrence. The risk profiles are evaluated based on their level of acceptability (Renn 2011). Low-risk situations or activities are considered highly acceptable. Risk management is applied to risks considered tolerable. It entails a suite of mitigation measures to reduce the adverse consequences of a risk. Risk communication/participation entails educating the masses through interactions to disseminate information related to the risks (Renn 2011). The aim is to build trust relationships in risk management through multi-actor inclusion.

The cyclic process of risk governance occurs in a logical sequence of five phases: pre-assessment, appraisal, characterization and evaluation, risk management, and communication (Roeser et al. 2012). The individual phases and their specific components are described below.

Pre-assessment Phase

The pre-assessment phase is the screening stage of the risk governance process. Here, the actors consider diverse issues related to a specific risk. In addition, the different stakeholders review the risk indicators and practices at this stage. The main components of the pre-assessment phase include “problem framing, early warning, pre-screening, and the determination of scientific conventions” (Roeser et al. 2012, p. 51). The purpose of risk framing is to explore the multi-actor perspectives and establish a common understanding of the risk issues. Based on an agreed risk frame, the signals or indicators of the risk/problem can be monitored.

Early warning helps identify indicators that confirm the existence of a risk. It entails an exploration of institutional capabilities for monitoring early warning signs of risk within an organization (Rossignol, Delvenne & Turcanu 2015). Pre-screening encompasses preliminary analysis of risk candidates and prioritizing them based on probabilistic models. It also entails identifying the appropriate evaluation and management route for each risk candidate. It is followed by a determination of the main “assumptions, conventions, and procedural rules” required for the assessment of the risk (Rossignol, Delvenne & Turcanu 2015, p. 137). The stakeholder emotions related to the risk issues are also considered in this step.

Risk Appraisal Phase

The purpose of risk appraisal is to create societal standards or scientific thresholds for risk. It also gives a knowledge base for identifying appropriate risk mitigation or containment approach. Its main components include risk assessment and concern assessment (Roeser et al. 2012). A risk assessment identifies the cause-effect relationship of risk as well as its probability of happening. It may involve risk identification and evaluation to estimate its severity. The objective of concern assessment is to explore the stakeholder’s anxieties and fears related to the risk (Roeser et al. 2012). It also illuminates the socioeconomic impacts of a risk-based on stakeholder perceptions.

Risk Characterisation/Evaluation Phase

This phase involves estimating how acceptable or tolerable a risk is to the stakeholders. Therefore, the two components of this phase are risk acceptability and tolerability. A risk problem considered acceptable has lower adverse impacts on health/environment than a highly unacceptable one (Karlsson, Gilek & Udovyk 2011). This means that the risk does not require mitigation efforts. On the other hand, a tolerable risk has significant trade-offs between benefits and adverse effects. As a result, specific mitigation measures are adopted to reduce the negative effects. Characterization helps generate an evidence base from the outcome of the risk appraisal phase. In contrast, evaluation involves consideration of extraneous factors relevant to the risk.

Risk Management Phase

The risk management phase involves the development and application of mitigation actions geared towards averting, diminishing, or retaining risks. It proceeds through a six-step process that culminates in an optimal option for risk management. The first component involves the formulation of an array of options for addressing the risk (Roeser et al. 2012). This initial step relies on the acceptability-reliability considerations relevant to the specific risk. The next step involves the evaluation of the options based on specified criteria, e.g., sustainability or cost-effectiveness (Karlsson, Gilek & Udovyk 2011). Thirdly, a value judgment based on the weights assigned to each criterion is applied to the options. Subsequently, the best option(s) is chosen for further consideration in the fourth step. The fourth and fifth steps cover the execution of the best risk management strategy and monitoring and evaluation of its impact on the reversibility of the risk.

Communication Phase

Risk communication is an ongoing activity during the risk governance process. Its aim is to enlighten non-participating stakeholders regarding the risk decisions emanating from the preceding phases (Roeser et al. 2012). Additionally, risk communication helps support informed choices by stakeholders based on the consideration of societal/individual interests, fears, values, and resources (Roeser et al. 2012). As a result, conflicting perspectives are managed to arrive at a consensus risk management strategy for the institution. Effective communication is also required between policymakers and experts/assessors to avoid bottlenecks related to communication lapses.

The OCC’s Risk Governance Framework

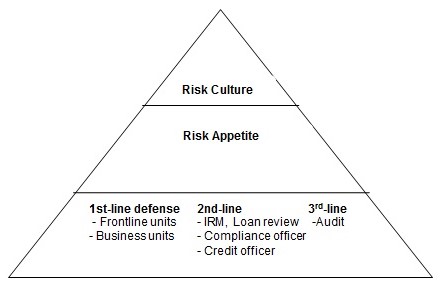

Another existing framework is the one proposed by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency [OCC] for risk governance in the financial industry (Figure 4). This model is intended to help the board/management of banks to establish an institutional risk culture, promote compliance with the risk appetite, and create a risk management system for the identification, measurement, and control of risks (IFC 2012). The OCC’s framework comprises three additive steps – risk management system, risk appetite, and risk culture. It takes into consideration the various risk categories common in the financial sector. Examples include interest rate and price, which portend a significant risk to an institution’s financial performance.

Banks use different risk governance models depending on the nature of their operations and corporate strategies. In banks, the board/management oversees the formulation, execution, and evaluation of a risk governance model through independent assessments. Subsequently, based on the outcomes of the assessment, some or all of the elements of the model are reviewed to enhance its efficacy. In this structure, the institution’s senior management does the role of maintaining the framework and managing factors related to the defined risk appetite (Polk 2014). It also regularly informs the board about the institution’s risk profile and potential risks. The specific components of this framework are described below.

Risk Culture

In the OCC’s framework, risk culture covers the institutional “values, attitudes, competencies, and behaviors” that define the bank’s risk governance practices and decisions (Polk 2014, p. 14). It is, therefore, a subset of the organizational culture. The board plays a critical role in creating a sound risk culture through enhanced risk awareness and communication of the acceptable risk levels to the staff. This ensures that the employees make decisions that conform to the defined risk appetite or acceptable risk thresholds. Besides the board, the bank’s senior management promotes a positive risk culture through staff incentives and sanctions for unacceptable behavior (Polk 2014). The management is required to identify and address risk-taking behavior or actions that go beyond the minimum thresholds.

Risk Appetite

In the OCC’s framework, risk appetite is considered an important element of sound risk governance. It entails the “aggregate level and types of risk”, which the board and the senior managers can assume to realize the institution’s strategic goals or objectives (Polk 2014, p. 13). However, a bank’s risk appetite must not exceed its capital or liquidity level. The establishment of a risk appetite involves concerted efforts from the board, senior managers, supervisors, and front-line staff. Furthermore, its execution requires effective interactions between the various stakeholders involved in the management system. Information about the bank’s risk appetite should be conveyed throughout the institution to ensure that risk decisions are aligned with the acceptable risk thresholds. The risk management and front-line units should track, evaluate, and report the risks based on the risk appetite policy.

Risk Management System

The third component of the OCC framework is the risk management system. It encompasses policies, processes, and staff involved in the identification, measurement, tracking, and management of risks (Polk 2014). The nature of a bank’s risk management system depends on the economic conditions that the organization operates in and the complexity of its organizational structure. It entails three defensive structures. The first defensive structure involves “the frontline units or business units that create risk” (p. 46). The frontline/business units are the primary risk-takers, and therefore, they must operate within the accepted risk appetite thresholds. The second defensive structure is the internal risk management (IRM) unit, which oversees the risk-taking activities of the frontline units (IIA 2013). The IRM also recognizes, measures, and tracks emerging risks and participates in risk decision-making in the bank (IIA 2013). Ordinarily, the IRM comprises the credit officer and/or credit review manager. The final defensive structure in this framework is the audit unit, which facilitates external validation. It implements internal controls to ensure effective risk governance within the institution.

The International Finance Corporation (2012) extends the OCC’s risk governance framework by including the concept of conflict of interest. The elimination of possible conflict of interest situations is essential for effective risk governance in the financial sector (IFC 2012). It entails separation of duties, independent management of activities, and adequate revenue control systems in the bank. Effective communication is also required in staff education, deliberations, and reporting of risks in financial institutions.

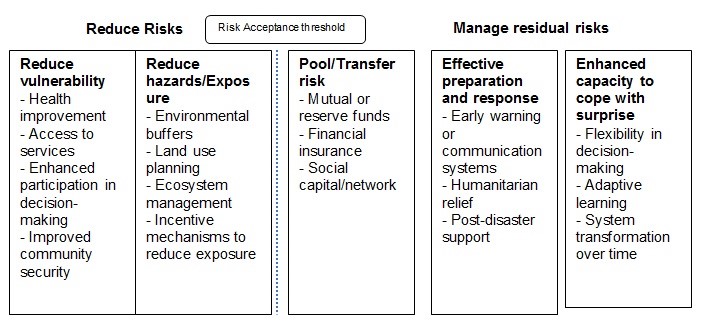

IPCC Risk Governance Model

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s [IPCC] (2012) developed a model for managing risks related to natural disasters. The key components of this model include methods for reducing risks and for managing the residual risk related to environmental hazards. The reduction of risks focuses on minimizing vulnerability, hazards, and exposure (IPCC 2012). It also entails sharing or transferring the risk through mutual/reserve funds, financial insurance, and social capital.

In the public sector, risk vulnerability is reduced through society-level actions such as access to essential services, improvement in community security, and increased participation in decision-making. On the other hand, the reduction of the exposure levels to natural risks can be achieved through land use planning, incentive mechanisms, and ecosystem management, among others (IPCC 2012). The risk reduction phase of the IPCC framework also entails the pooling or transferring of risks. This requires interventions like reserve funds, insurance cover, and social networks.

The second phase of this framework comprises the management of residual risks/uncertainties. The natural risks are managed through effective preparation and response and the enhancement of the capacity to deal with surprises (Hooper 2014). In this regard, the government can manage residual risks by implementing early warning systems, post-disaster support, flexible decision-making systems, and adaptive learning, among others. The IPCC model is illustrated in figure 5 below.

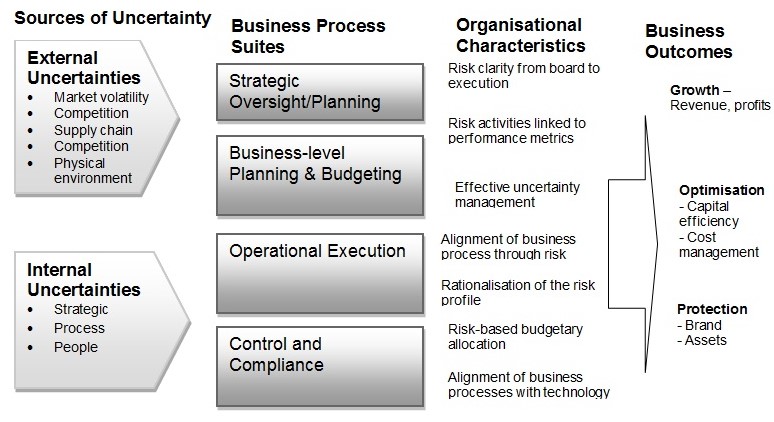

Risk-enabled performance management (REPM) Framework

Private sector organizations are shifting to a performance-based approach to the management of risks. Risk-enabled performance management (REPM) focuses on value creation by supporting robust decision-making and the identification of business opportunities while minimizing uncertainties or risks (Palermo 2011). Therefore, using the REPM framework (Figure 6), organizations can achieve risk-enabled performance as opposed to simple identification and measurement of risks. In this way, the firm can obtain additional value from its risk management initiatives – a benefit that may not possible when the focus is on risk avoidance or minimization alone. In the REPM framework, multiple business processes and components interact to create value for the organization. The main components of this framework include strategic oversight/planning, business-level planning, operational execution, and monitoring and compliance.

Strategic Oversight/Planning

This component focuses on a range of board or senior management-level activities that trigger the development of a risk-enabled organization. The strategic oversight function entails establishing risk governance “structure, roles, and responsibilities” of each individual within the organization (Palermo 2011, p. 9). This role is achieved through delegation and performance evaluation. It is also incumbent upon the executive leadership to specify the appropriate risk appetite for the organization. In this way, the capital allocation and investment decisions can be aligned with the acceptable risk thresholds. The oversight role also entails the identification of emerging risks and performance management to realize the value of the risks.

Business-level Planning

It encompasses the conversion of business strategies into plans and budgeting. The organization can use planning tools to analyze the “types and levels” of each risk inherent in a given investment (Palermo 2014, p. 328). In this way, the organization will create a basis for risk-based investment and budgeting.

Operational Execution

This step covers the implementation of strategic plans from the previous stage. The operational reviews should consider the identified risk limits and appetite in evaluating performance (Palermo 2014). The risk tolerances indicate how well the firm’s operations are aligned with the established risk appetite. Another dimension of operational execution is the re-evaluation of risks linked to operational activities. The aim is to minimize possible ‘surprises’ or uncontrollable events in organizational operations.

Monitoring and Compliance

This phase entails audit and compliance measures. It involves the alignment of the “monitoring processes with the risk profile” to detect redundancies and inadequacies in the monitoring function (Palermo 2014, p. 331). An in-depth evaluation of the risk profile and the deployed monitoring measures can reveal issues or problems that could precipitate costly risks. Thus, the approach reduces costs and improves the efficacy of risk surveillance. The REPM framework was shown to give a clear risk profile of a power plant and facilitate more efficient budgeting for risk mitigation programs.

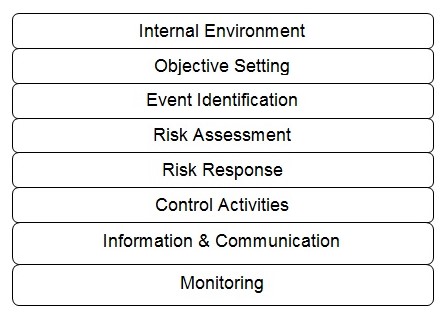

Enterprise Risk Management Framework

Enterprise risk management (ERM) supports the effective management of uncertainty in organizations. It entails a comprehensive model for the identification, measurement, prioritization, and management of risks that threaten business activities or operations (PWC 2015). The ERM framework involves the development of a portfolio view of risks based on organizational operations at all levels, including enterprise-level, division/subsidiary, and business-level processes. The senior management first explores the interrelationships among risks before formulating a portfolio view from a business unit level and entity level (PWC 2015). The ERM framework comprises eight interrelated components. They include internal environment, objective setting, event identification, risk assessment, risk response, control activities, information and communication, and monitoring (PWC 2015).

Internal Environment

A focus on the internal environment creates a risk management philosophy that leads to an increased recognition that both anticipated and unanticipated events may happen (Karim 2011). An internal environment focus also helps define the organizational risk culture and the actions that affect it.

Objective Setting

The formulation of business objectives should involve a risk strategy. Such an approach establishes an organization’s risk appetite, i.e., the board- and management-level view of the acceptable risk levels. Through objective setting, the management can align risk tolerance with the established risk appetite.

Event Identification

The event identification step helps distinguish risks from opportunities. Risks involve events that impede the attainment of the business objectives, while those with a positive effect constitute the opportunities for strategic action (PWC 2015). Event identification is critical in each decision level, when implementing a process or system changes, and for new projects. The initial risk identification process helps identify a risk profile for the organization. Thereafter, more risks are identified for inclusion in the risk profile, as the event identification step becomes a part of the organization’s culture.

Risk identification entails the identification of the incidents, whether internal or external, which could impede strategy. It also addresses the internal and external factors that affect an organization’s risk profile. The risks are grouped based on their sources for easier root-cause analysis and assignment of mitigation responses (Ng 2015). The major sources of risk include political influences, decision-making, human capital, natural events, and regulatory issues. The other sources of risk may be fraud, supplier factors, technology, and competitive pressures.

Risk Assessment

The assessment of the identified risks is the second step of the ERM framework. The assessment allows the management to formulate appropriate risk responses based on the likelihood/probability of occurrence and anticipated impact – using a risk rating scale (Ng 2015). The likelihood rating ranges from highly certain to unlikely to occur. In contrast, the risk impact rating focuses on the effects of each risk, including financial costs, missed operational milestones, regulatory breaches, failure to meet strategic objectives, and managerial staff turnover. A risk map is constructed from the results of the assessment.

Risk assessment gives a comprehensive picture of how potential risks may influence objectives. Therefore, the assessment focuses on the likelihood and impact and involves both qualitative and quantitative techniques. The risk is measured on an “inherent and residual basis”, taking into account the predefined time and objective horizons (Ng 2015, p. 14). The aim is to inform future actions or risk responses.

Risk Response

In this step, the entity identifies and develops responses to each identified risk. In this regard, the organization considers multiple options based on its “risk appetite, cost-benefit analysis of the risk, and the degree to which a response will reduce the risk impact or likelihood” (Domokos et al. 2015, p. 8). After an analysis of a suite of risk/response options, the organization selects and implements an optimal response to mitigate the risks. In this case, the organization’s inherent and residual risks are measured during the execution of the risk response to achieve the desired risk level. Inherent risks differ from residual ones in the sense that they occur prior to the execution of any risk control or response.

The response options include the portfolio of management actions aimed at controlling or preventing the risk. The management can choose to mitigate, exploit, accept, transfer, or avoid a risk. Risk mitigation encompasses actions taken to minimize the likelihood of occurrence or impact of a particular risk (PWC 2015). Mitigation activities may include budget controls, forecasts, enhancing accountability, staff motivation programs, and building appropriate skill sets (Andreeva, Ansell & Harrison 2014). Risk exploitation allows an entity to leverage on opportunities presented to grow through activities such as strategic alliances, business portfolio expansion, innovative product development, and organizational restructuring.

The management can also choose to accept the risk impact and probability of occurrence. Risk transfer, as a response option, involves activities meant to shift the loss/impact to other parties. It can be achieved through outsourcing, insurance coverage, and hedging (Andreeva, Ansell & Harrison 2014). Risk avoidance involves activities meant to prevent hazards from occurring. They may include ceasing operations, divestiture, or reducing the scale of operations.

Control Activities

This step involves an ongoing process of tracking and reviewing the risk profile and responses (Mathews & Kompas 2015). The aim is to ensure that the management of risks occurs as planned, determine the relevance of the risk responses being executed, and track the impact of the activities on the risk profile. In addition, the control activities can inform new response plans for emerging risks. Risk monitoring comprises diverse methodologies for review, assurance, and auditing risks. The assurance techniques involve post-implementation reviews, performance appraisals, and quality reviews, among others.

The measurement of a response option should involve its efficiency and effectiveness (Walker, Tweed & Whittle 2014). In this case, efficiency indicates the execution costs related to finance/budget and time. In contrast, effectiveness indicates the extent to which the responses minimize the risk impact or probability of occurrence (Walker, Tweed & Whittle 2014). To achieve a higher level of response efficiency and effectiveness, the control activities should be incorporated into the current business processes at all levels of the organization.

Information and Communication

This step involves reporting the risk in terms of its status and related responses. Various employees play different roles in the ERM process. The board plays a role in policy design and ERM framework development while the management oversees the implementation process. Having a risk reporting structure helps address issues that affect the response plan being executed. It helps staff responsible for various ERM activities to obtain pertinent information to effectively carry out their roles. The internal reporting process involves the operational staff, management team, senior leadership, and the board. In contrast, external reporting involves the communication of the risk profile and responses to the stakeholders.

Monitoring

The efficacy of the ERM elements is monitored regularly to determine the impact on the risk profile. The ERM monitoring may involve ongoing control activities or independent evaluations, such as audits and reviews.

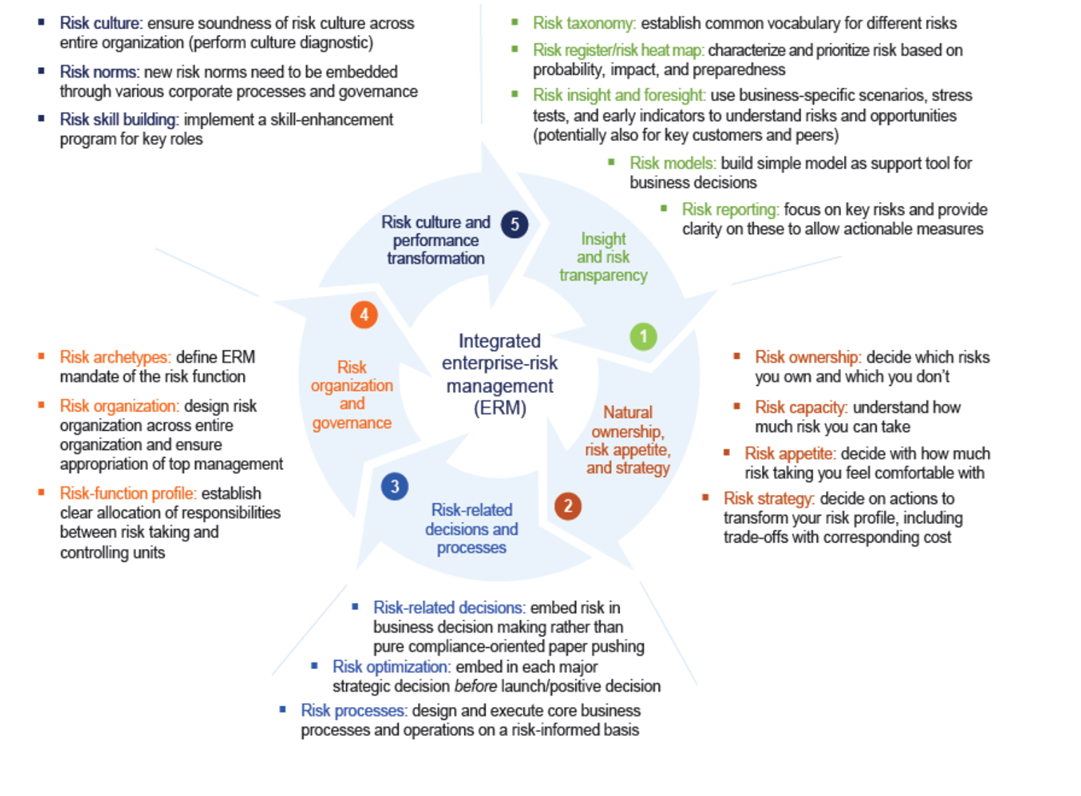

Integrated Enterprise-Risk Management Framework

The banking sector faces unique challenges that pose a threat to growth. The integrated enterprise-risk management (ERM) framework provides a new approach to risk in the banking industry, which is structured around five dimensions. It places the responsibility of developing the ERM capabilities at the hands of a firm’s board. The five core dimensions of the integrated ERM framework include “risk transparency and insight, risk appetite and strategy, risk-related business processes and decisions, risk organization and governance, and risk culture” (Brodeur et al. 2010, p. 1). The recommended actions in each of the five steps are described below.

Risk Transparency and Insight

Most firms have adopted risk identification processes for the early detection and prioritization of risk events. The companies produce annual risk reports cataloging the most significant risks and their likelihood of occurrence and impact. The only downside to this approach is that they omit company-wide risks, fail to reveal the causes of the risks and overlook the multiplicity aspect of risks (Lamarre & Pergler 2009). A robust risk identification mechanism should uncover the root causes. The main components of risk transparency and insight proposed under the integrated ERM framework are risk taxonomy, a prioritized risk heat map, risk insight and foresight, risk models, and risk reporting.

Risk taxonomy entails creating a common vocabulary for the risk types experienced or likely to occur (McNeil 2013). The rationale is to facilitate risk identification and classification for effective management and control. A prioritized risk heat map sorts the risks based on their potential impact, level of preparedness, and likelihood of occurrence (McNeil 2013). One recommended strategy for building a robust heat map is through adequate risk estimation that takes into consideration all the risk drivers. A good heat map can also be generated if a transparent and coherent approach is taken in naming and classifying risks across all the business units. In addition, besides likelihood and impact considerations, other variables – preparedness and lead-time –should be taken into account when constructing a risk heat map.

Another element of the first dimension of this framework is risk insight and foresight. It entails using scenario testing, indicators, and stress tests to explicate high-priority risks at the board level (McKinsey & Company 2013). Firms often use these methods to explore up to five risks that are significant to business operations. Constructing risk models can also provide a basis for business decisions for organizations. The subsequent step entails compiling insightful reports on key risks to illuminate the key actionable measures. Well-designed and integrated risk reports should highlight the board’s assessment of the risks, including the tradeoffs considered and the decisions made to facilitate consistent information flows across the organization (McKinsey & Company 2013).

Natural Ownership, Risk Appetite, and Strategy

This step entails deciding on the risks an organization owns, its risk capacity, risk appetite, and risk strategy. A firm’s risk appetite depends on its risk capacity, which describes a company’s ability to “withstand a risk when it materializes into actuality” while staying clear of undesirable effects or constraints (Brodeur & Pritsch 2008, p. 12). The determination of risk capacity depends on the type of risk and may involve Monte Carlo simulations or discrete scenarios that would then help predict future trends. The risk appetite indicates how many risks a firm will take based on its capacity (McNeil 2013). From its risk appetite, a company can determine the risks it can own. Risk ownership describes the risks a firm has the capacity to control and exploit in order to realize its competitive goals (McNeil 2013).

At the same time, a firm needs to define the risks it wants to mitigate, transfer out, or avoid at this point. Based on the risk appetite and ownership, a risk strategy for the company is formulated. The strategy represents a coherent message or affirmation of the risks that the company has decided to take or transfer. It is normally adopted in the organization’s strategic plan and communicated to the shareholders.

Risk-related Decisions and Processes

This step entails the integration of risk considerations related to strategic planning, resource allocation, and financing in risk-related decisions and processes (Brodeur et al. 2010). A firm’s strategic choices should reflect its risk appetite/capacity. Strategic planning considers the risk assumptions and uncovers the return/risk tradeoffs inherent in a project. Resource allocation gives key personnel the green light to take risks based on the established risk appetite. On the other hand, financing or hedging decisions by the board would depend on the defined risk capacity and potential impacts. In the banking sector, the quality of risk-related decisions/processes depends on how well the liquidity risk is managed in the organization (Brodeur et al. 2010). Therefore, in banks, risk-related decisions are aimed at managing and controlling liquidity risks.

This integrated ERM dimension encompasses three elements: risk-related decisions, risk optimization, and risk processes. Risk-related decisions entail the grounding of risk in all business decisions, as opposed to working to meet regulatory requirements. Similarly, risk optimization must also be embedded in all strategic decisions to achieve favorable return/risk tradeoffs. In addition, the core business operations of the firm must be risk-based to ensure risk-informed responses and actions across all levels of the organization.

Risk Organisation and Governance

The role of risk oversight belongs to a firm’s board. In the risk governance structure, the board collaborates with the line managers and risk officers on risk issues and ensures that the ERM program is optimized for the specific risks that the firm faces. The oversight role also includes the evaluation of risks through the board-risk committee interactions and dialogue (Pergler 2012). The aim is to remove bureaucratic processes that impede effective risk governance. An ERM organizational model may involve a risk officer reporting to the firm’s chief executive officer and leading teams tasked with the management of various risks affecting the organization.

The basic components of an ERM organizational model include risk archetypes, risk organization, and risk-function profile. Risk archetypes entail defining the mandate of an ERM function within the finance unit to introduce risk thinking in managerial processes (Beckers et al. 2013). Risk organization involves the design of enterprise-wide processes, including risk policies/guidelines and resource allocation. Creating a risk-function profile can help the risk team obtain traction in a firm’s business. It entails a clear allocation of duties and obligations of the risk-taking personnel and risk management unit.

Risk Culture and Performance Transformation

The final ERM dimension focuses on risk culture and performance. Risk culture emerges when decision-making behaviors that involve an evaluation of risk/benefit tradeoffs become the norm in the organization. It is defined as the “norms of behavior for individuals and groups within a company that determine the collective willingness to accept or take risks” (Brodeur et al. 2010, p. 5). Appropriate risk norms should be embedded within the organization through corporate-level processes and governance.

A cultural survey or diagnostic can help determine the flaws in a firm’s risk culture, necessitating the need for a change. Mikes (2011) provides four strategies for effecting a sustainable cultural change related to risk in an organization, namely, fostering conviction/understanding among employees through incident reviews, role modeling by supervisors, talent and risk skill development, and establishing formal structures/processes for performance appraisal and compensation. According to Mikes (2011), the process of achieving a high-level risk culture change encompasses four steps: diagnostic risk culture, target-risk norms articulation, development of multilayer initiatives, and ongoing monitoring of risk governance in the organization. Therefore, the risk culture journey culminates in positive risk norms being embedded in all organizational structures and processes.

Risk IT Framework

Public organizations and private enterprises face IT risk in addition to strategic, operational, and market risks, among others. Poor IT security in organizations increases the likelihood of business risks related to cyber threats. The management of such risks is critical to the success of an organization. The adoption of IT brings immense benefits to an entity; however, it also comes with risks.

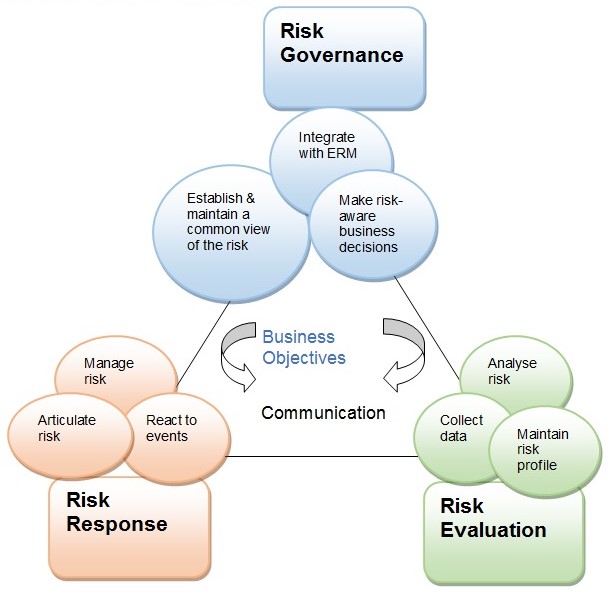

Since IT lies at the heart of operational efficiency, IT risk is regarded like other enterprise risks that impede the achievement of strategic goals (Deloitte 2014). In most organizations, the management team does not handle IT risks but delegate this role to the IT department. The Risk IT framework (Figure 8) helps businesses integrate IT risk governance into the ERM to support risk-based decisions. The framework also highlights the nature of the risk as well as the organization’s risk appetite and tolerance to facilitate appropriate risk responses. Therefore, it supports risk-aware decisions by organizations.

The Risk IT framework is founded on six core principles that support risk governance in organizations. The organization must continuously connect the risk responses to the business objectives, align the management of the risk to its ERM, balance the risk costs and benefits, enhance risk reporting, establish top leadership risk appetite, and incorporate these processes into the day-to-day business activities (Deloitte 2014). The Risk IT framework contains three components or domains, namely, risk governance, risk response, and risk evaluation (Svata & Fleishmann 2011).

Risk Governance

This risk IT domain ensures that risk management practices are integrated with the business processes for enhanced risk-based performance. Risk governance encompasses three processes, namely, integration with ERM, formulation of risk-based decisions, and establishment/maintenance of a common risk view (Svata & Fleishmann 2011). The goals of risk governance are to achieve acceptable risk appetite and tolerance, enhance role clarity in IT risk management, promote risk awareness, and establish a risk culture in the organization.

In the risk IT framework, risk appetite is defined as the “broad-based amount of risk” that an entity can accept in pursuing its mission (Svata & Fleishmann 2011, p. 51). In contrast, risk tolerance means the acceptable variation around organizational objectives (Svata & Fleishmann 2011). These two concepts help an organization establish a coherent view of the risk at all levels. However, they are subject to changes in technology, firm structures, and macro environment factors. Therefore, a firm should continually evaluate its risk portfolio to determine its risk appetite at different times. On the other hand, risk tolerance can be influenced by mitigation costs. Indeed, in some cases, the cost impact of mitigation can go beyond its resources, resulting in a higher risk tolerance (Svata & Fleishmann 2011). Thus, the cost-benefit trade-offs determine the risk levels that an enterprise is willing to tolerate.

The framework also defines the responsibilities of the people involved in IT risk governance. Various individuals are charged with the responsibility of managing IT risks. The board, chief executive officer, and chief risk officer as well as the personnel drawn from the enterprise risk committee play a role in risk governance. In contrast, accountability applies to individuals who allocate resources or authorize specific actions, e.g., the board. Besides establishing responsibilities and accountabilities, risk governance enhances risk awareness and communication in the organization. Risk awareness entails the recognition of risks for specific management action. In contrast, risk communication enhances the discussion around risks to increase the management’s understanding of its effects for appropriate responses. An open risk communication practice enhances risk awareness among stakeholders and increases transparency in risk governance.

Risk Evaluation

The goal of the risk evaluation component of the Risk IT framework is to identify, analyze, and provide “IT-related risks and opportunities” in the organization (Flemig, Osborne & Kinder 2015, p. 6). It entails three processes, namely, analyzing the risk, establishing an institutional risk profile, and collecting data. The goals are to highlight the business impact and develop risk scenarios. The evaluation entails converting IT risks into business risks. It requires the IT and the business teams to develop a mutual understanding of the risks that need management. The stakeholders must have a basic understanding of the risks impacting the business objectives. In this regard, the IT person should know the impact of the identified IT risks on strategic objectives. Similarly, the management should understand the IT-related risks that affect business processes (Fleming, Osborne & Kinder).

Risk evaluation helps define the link between anticipated IT risks and their impact on operations through the expression of such risks in business terms. The methods prescribed in the Risk IT framework for risk evaluation include the balanced scorecard, COSO ERM, and the COBIT information criteria (Potts & Kastelle 2014). Risk scenarios are important in IT risk governance. The scenarios are utilized in risk analysis to determine the likely impact of a risk to the organization. Two complementary methods are used to develop the risk scenarios: a top-down approach and a bottom-up approach. The latter utilizes generic scenarios to develop improved scenarios tailored to the organizational realities, whereas in the former approach scenarios are derived from the business objectives.

Risk Response

The purpose of risk response is to address IT risks in a cost-efficient way and according to the organization’s priorities. The essential processes in this domain of the Risk IT framework include risk management, reaction to risks, and risk articulation (Svata & Fleishmann 2011). This step encompasses the definition of risk response and identification of the key performance indicators (KPIs) based on project objectives. The KPIs indicate whether an organization is likely to face a risk that outstrips the established risk appetite. The choice of the KPIs is dependent on micro and macro environment factors, the size of the organization, and the prevailing regulatory regime (Svata & Fleishmann 2011). The KPI selection process should involve stakeholders to achieve buy-in and support. Further, the selection should involve consideration of the major performance indicators and root causes. The selected KPIs must meet the following criteria: optimal business impact, high sensitivity, and reliability (Claudia, Tehler & Wamsler 2015).

The reason for providing a risk response definition is to align the identified risk with the established risk appetite (Claudia, Tehler & Wamsler 2015). This implies that defining a response will ensure potential residual risk falls within the acceptable tolerance threshold. The possible risk response options include avoidance, reduction/mitigation, sharing/transfer, and acceptance. The choice of the risk response option depends on its cost (capital, wages, and operational costs), the significance of the risk as shown in a risk map, the efficacy and efficiency of the response, and the organization’s capacity to execute the response (Hooper 2014). Therefore, an entity should prioritize the response options based on the above criteria and select the optimal risk response.

Issues learned from Literature

Summary

In this chapter, a systematic review of scholarly literature on risk governance has been done. Although risk governance definitions vary widely, they all feature multi-actor involvement and transparency/accountability principles. It can be conceptualised as multi-stakeholder network/process for evaluating and managing public risks. Risk governance provides a framework for the involvement of all actors in responsible management of risk problems. The major risk governance frameworks reviewed in this research include the Brown and Osborne’s (2013) model for public service innovation, IRGC model, modified IRGC framework. Risk governance is a cyclic process comprising five interconnected phases that culminate in an optimal risk management option for an identified risk. The adopted risk governance approaches in public service organisations in countries such as the UK focus on the institutionalisation of risk analysis tools to support policy/decision rationales and accountability. The identified issues of risk governance in the public/government sector include the communication/inclusion of multiple stakeholders, multidisciplinary knowledge/experience integration, routines, and flexibility of regulatory approaches.

The review has examined eight existing frameworks of risk governance in various sectors. The first one is the Brown and Osborn’s (2013) framework, which is applicable in the public-sector innovation. It links technocratic, decisionistic, and transparency to different possible formulations of innovation, i.e., evolutionary, expansionary, and total innovation. Evidently, this framework is too simplistic to cater for the diverse multi-actor processes involved in public sector risk governance. The second framework reviewed is that provided by the IRGC. Its five phases – pre-assessment, appraisal, characterisation and evaluation, management, and communication – provide a foundational theoretical lens for risk governance across all sectors. However, clearly, the framework is too linear to reflect the iterative and integrated nature of public sector decision-making. Nevertheless, it provides a good starting point for the development of a more integrated framework of risk governance. To avoid the problem seen in the earlier IRGC model (linearity), the modified IRGC framework by Renn, Klinke, and van Asselt (2011) involves a cyclic process. It also introduces the element of multi-actor inclusion in the pre-estimation stage.

The problem seen in the IRGC framework also occurs in the OCC’s framework, which is meant for corporate risk governance in banks. This framework involves additive steps of establishing a risk management system, risk appetite, and risk culture that proceed in a logical sequence. In contrast, the IPCC model highlights a host of activities for reducing natural risks and managing residual risk events. The REPM framework centres on value creation for the organisation through oversight/planning, business-level planning, operational execution, and monitoring and compliance of corporate risks. In contrast, the ERM framework focuses on the unit-level and entity-level business risks that threaten a firm’s operations. The risk IT framework gives integrated activities for risk governance, risk evaluation, and risk response to help organisations make risk-aware decisions.

Four key issues or themes emerge from the literature reviewed. The first one is the diversity of stakeholders and breadth of their interactions in a public risk environment. The appropriate risk appetite for organisations is another issue evident in literature. Effective risk communication/reporting that reflects the diversity of stakeholder backgrounds and interpretations is another key issue in this research. Finally, the challenge of embedding a new risk mind-set or culture comes up as a significant issue in risk governance literature.

Literature review II: The role of Internal Audit Function in governance assurance

Introduction

In today’s business environment that is characterised by rapid economic globalisation and the stricter legal landscape, organisations are forced to review their strategy periodically to manage financial and non-financial risks to thrive. These conditions also demand a redesign of organisational structures, processes, and systems in a project context. Efficient management of risks in organisations is crucial for firms to navigate increasingly complex uncertainties, including natural disasters and fraud risks (Dafikpaku 2011). Corporations control risks as a routine business operation. However, to withstand growing economic globalisation waves, it is essential for both public and private institutions to adopt effective mechanisms for risk identification, assessment, and response.

The internal audit function evolved from risk governance to strengthen a firm’s financial risk management practices (Huibers 2013). Organisational stakeholders would want an efficient internal process for managing uncertainties, as opposed to depending solely on external audit reports. They also require regular information about the performance of the firm to inform their investment decisions. The risk-based audit function is meant to enable organisations to meet stakeholder interests, thrive in a rapidly changing business environment characterised by financial uncertainties, and respond to market and regulatory requirements (Burton et al. 2012). The aim is to enhance enterprise-wide operational efficiency to minimise risk, support financial reporting, and avoid failures (Huibers 2013).

From this background, it is clear that the risk-based approach to internal control influences risk governance. The efficient evaluation of departments or units can uncover control weaknesses that expose the organisation to risk. Results from surveys of auditors as respondents can help strengthen risk management processes, such as error detection and fraud discovery (Ravindran et al. 2015). The process ensures that financial statements are accurate and reliable. Auditing is a standard practice for preventing accounting fraud risk in organisations. Further, a risk-based audit can reveal risks with a considerable impact on financial reports (Ravindran et al. 2015). Subsequently, a significant management focus is directed towards those areas.

Financial uncertainties often arise from organisational records and change management. Businesses face constant pressure to innovate and remain competitive. As a result, they must manage change internally to control new risks. Proactive risk management of an organisation’s financial and nonfinancial information is critical during the transition period. Such an approach will result in an efficient decision-making process in all areas, including records management (Huibers 2013). Therefore, a coherent risk governance policy can ensure that departmental heads cooperate, particularly when implementing mitigation measures to preserve financial/nonfinancial information.

This chapter reviews the relevant literature on risk-based audit processes in public sector projects. The fundamental element examined is the internal audit function in the context of risk governance. The chapter involves a synthesis of existing knowledge in this area. Because of the significance of the internal audit in risk governance, this review begins with a definition of the internal audit function and its role in the public sector, organisational projects, and governance assurance. The analysis clarifies the elements of a maturity model developed in the previous chapter, including strategy, risk appraisal and insights, risk decisions and implementation, etc.

The Internal Audit Function