Introduction

The merger between Westpac Corporation and St. George Bank came when the two firms were performing very well. Westpac Corporation was considered one of the best financial institutions in Australia, while St. George Bank had built its special niche as a family bank. The merger of the two firms, therefore, resulted in a huge firm with a massive capacity to meet the demands of the market in various segments of the finance industry. According to Barney (2010, p. 57), when two large firms merge, there are numerous issues that have to be addressed. This scholar says that one of the issues that the management has to consider is how the employees will be managed under the bigger umbrella. At Westpac Corporation, this was an issue that had to be addressed. The two firms had their own employees working under the terms and conditions set by the two firms separately. In this new management approach, the new management unit had to come up with new strategies in order to ensure that the firm operated successfully.

According to Jensen (2011, p. 650), when two large firms are merging, the first issue that has to be addressed when it comes to human resource issues is how the management will be structured after incorporating the two managements into one unit. Hedlund (2004, p. 33) says that mergers are different from acquisition and takeovers. In acquisition, the purchasing firm will always take over all the management issues and will solely be responsible for the appointment of all the employees at all levels of management. This is always not the case when it comes to mergers.

In mergers, the two firms will operate as partners, each having a specific role to play. In this case, therefore, it was a little challenging to come up with a management structure that would help in the smooth running of this new firm. Given the fact that Westpac was a much larger firm with a larger asset base as compared to St. George Bank, its management took the overall management of the new firm. As Stahla (2005, p. 78) observes, in cases where two firms are merging, and one happens to have a larger asset base than the other, the one with the larger asset base would be allowed to take the overall management authority of the new firms. This is because they have a larger share, hence, larger interest in the new arrangement. The chief executive officer of Westpac Corporation, Mr. Gail Kelly, became the overall chief executive and managing director of the new unit created after the merger.

In this arrangement, however, there were some intrigues. For instance, Mr. Gail Kelly, who was the chief executive of Westpac Corporation and finally the newly created firm, had been a long-serving loyal employee of St. George Bank. He had risen in the ranks at St. George Bank and became the chief executive of this firm. In his tenure at the helm of this Bank, he saw it rise from a middle-sized financial institution into a fully-fledged bank. He left the firm as the chief executive to become the chief executive of Westpac a few months before the merger. Therefore, it may be possible that he was the one who steered the merger between the two firms when he was still the chief executive of this firm. Again, it was intriguing when Mr. Paul Fegan, the chief executive who had replaced Gail Kelly, announced his resignation upon the announcement that the two firms will be merging. His place was instead, taken over by Greg Bartlett. Even with some of these intrigues rocking the top management, this new firm, under the leadership of Gail Kelly as the chief executive, had to move to ensure that the objectives of the firm are achieved.

The management had to face the issue of harmonizing the workforce based on the new structure that was developed. One set of the employees were working under terms of contract set by Westpac Corporation, while the other was working under the regulations of St. George Bank. Some of the issues that the management had to address urgently included the issues of staffing after this merger, dumpsizing or rightsizing, survival syndrome, and cultural issues after the merger. According to Dowling (2008, p. 114), after merging two firms into one unit, there are some issues that the management have to address about the human resource before operations can officially begin. The staffing issue is important because the newly created firm would always need to hire new employees. It would be important to understand how this would be done in this new arrangement. Another issue that had to be addressed was rightsizing. When the employees of the two firms are brought into one unit, there may be a need to ensure that the new firm has the right size of employees. For instance, if each of the banks had hired a consultant in a similar field, there might be a need to drop one of the consultants after some time. Similarly, when each of the firms had lawyers, there might be a need to drop one (Regis 2008, p. 89). Another issue that will have to be addressed in this new system is survival syndrome. Lastly, the management will have to address cultural issues when merging. These four issues are discussed in detail below.

Staffing after Merger

According to Kotter (1990, p. 45), when firms are merging, it is always important to have clear information regarding the approach that should be taken in staffing the new firm. In most cases, firms would come together as a way of increasing their market coverage and capacity. As Rees (2003, p. 57) says, this means that through such mergers, a firm would experience considerable growth in its operations. This would mean that the firm would need to hire more employees to help in various duties. When these two firms came together, it appeared that Westpac Corporation took over most of the management policies. However, there was a twist that posed a challenge to the management. Even in this merger, the brand St. Georges Bank was still in existence. In fact, Yukl (2010, p. 96) reports that part of the agreement was that St. George Bank would operate in the suburbs of Sydney city as an independent firm. This meant that the management of this firm will be responsible for all the operational activities of such branches.

This arouses the question of who is actually in control, and how the two firms come to meet in issues related to the overall management of the firm. Pielstick (1998, p. 56) says that management is an important issue within a firm and that there should be a clear approach that should be taken when hiring new employees. There should be a single center of power where all the employees shall be drawing their authority. This would help in ensuring that the objectives of the organization are achieved as enshrined in their vision statement.

The case of a merger between the two firms posed a challenge on how the staffing was to be done. However, given the structure adopted by the firm, it was certain that the management of St. George Bank was subordinate to that of Westpac Corporation. However, St. George Bank had specific responsibilities and roles to play within this merger. It was a case of St. George being ruled by Westpac, but given authority to exercise to a given percentage within a defined jurisdiction. That is why even after the merger, St. George Bank still had its own chief executive. In the memorandum that was signed by the two firms, there were some selected branches of St. George Bank that were to operate exclusively under the management of St. George Bank. Other branches of St. George Bank were to operate under the new union. This was the clause that had to define how the union shall operate Aswathappa (2005, p. 93). According to Wilson (2005, p. 83), in such arrangements, the lead firm would have an exclusive control on issues that relates to the units under the union. In this case, the chief executive of Westpac Corporation will be responsible for all the activities taking place within the union. As such, he will have the authority to determine the right staff to higher within this new setting.

Then there are the units that remained fully under St. George Bank. These units would be managed by employees appointed by the chief executive of St. George. This chief executive will ensure that employees working within this place have the right qualification. He has the power to hire and fire these employees at any time and no authority will question this other than the board of directors of St. George Bank. It is important to note that while this chief executive will have all the executive powers in these selected branches, he shall remain answerable to the chief executive of Westpac Corporation for any action taken in the new firm. Another challenge that arises during the merger is on the issues of seniority when the two sets of employees get together (Pikula, 1999). After solving the issue of the top management, other managerial duties always pose a challenge. For instance, the deputy managing director at Westpac would want to retain the position in the new setting. On the other hand, the chief executive of St. George Bank would feel that after ceding ground on the top job, it would be obvious that the position would be left for him. This issue must be resolved in an amicable way where all the involved partners would feel that there is justice.

According to Huy (2002, p. 55), there are a number of approaches that can be used to solve this issue. One of the approaches would be to shake the entire management unit and hire them in positions they shall apply for based on merit. Buono (2003, p. 119) says that this may seem to be the most appropriate approach, but it is one that employees would try to avoid. For this matter, it is rarely applied, unless there is need to come up with radical changes within the firm. Another approach would be to redeploy the management, as would be appropriate, based on their rank and the number of employees commanded before the merger (Jacksona1992, p. 115). This strategy would have been appropriate for this firm. However, it did not employ it. Another strategy would be to employ the ‘status quo’ strategy. In this strategy, the management of the two firms will not be shaken up. The two merging units will operate under the command of the overall chief executive, but other operational duties shall be done by the management of the respective units (Kouzes & Posner 2002, p. 89). This is the approach that this merger has adopted. Each of the two firms operates semi-autonomously, only brought together by the top management. This explains the reason why the name St. George Bank was retained.

Rightsizing after Merger

Rightsizing is one of the factors that organizations cannot avoid. According to Grobler (2006, p. 37), in the current competitive market, firms are under intense pressure to cut costs of operation as it improves their efficiency. As such, many firms are currently automating their systems, and this means that they will always be forced to downsize their workforce. This is especially so after adopting the emerging technologies that many firms in the financial sector have embraced. After the merger of Westpac Corporation and St. George Bank, issues of rightsizing had to arise. These were two entities that were run separately but now had to operate as a unit. Given the fact that this was in the same industry, the possibility of duplication of duties and overlaps would be common. The management of this new firm had to find a way of rightsizing the human resource in order to increase efficiency and cut down costs of operations. It had to determine if there was a need for downsizing the number of employees or increasing it.

As Guest (2009, p. 276) says, the process of rightsizing in cases of the merger is a very delicate process that needs a lot of intelligence from the management. This is because of the two sets of employees, with each side trying to prove superior to the other (Kandula 2009, p. 17). In case the two merging firms have one of them being a major stakeholder, Rollinson (2005, p. 110) says that great care should be taken when undertaking the rightsizing process. While the employees would feel intimidated and, therefore, would need protection, employees from the larger firm would feel superior and would demand favors. The management must find a way of balancing the two divides in a way that after downsizing, the remaining employees will feel cared for and valued within the firm.

Despite the need to have the two merging firms operate in a semi-autonomous manner, it is important to appreciate that the semi-autonomy may be appropriate to a given level. In some cases, the top management may need to come up with human resource policies that affect all the employees in the firm irrespective of their area of operations. According to Fey (2012, p. 72), once there is a merger, rightsizing is a process that cannot be avoided. The management would have to determine duties that are duplicated after the merger of the two firms. The firm will have no otherwise but to retrench some employees in areas where there is duplication of work. When downsizing, the management will base the decision on the merit of all the employees. Employees with a track record of good performance within the firm would be retained in their respective position within the firm, or redeployed to other departments where they can perform better. Those whose capacity is below the expectation will have to be relieved of their duties from the firm.

According to Guesa (2001, p. 512), it is important to take into consideration what the law says about retrenchment when downsizing. The Australian government is very clear on issues regarding retrenchment. According to the law that governs the relationship of employee and employer, when a firm is acquired or merged with another, the responsibility of the employees is transferred to the new management (Klein 2003, p. 58). The government requires that when retrenching, the employer should give the employee some form of compensation as an appreciation. This is especially so when this comes before the written date (Hacker & Tammy 2004, 89). The chief executive will have the responsibility of ensuring that all those who are to be laid off are psychologically prepared so that they do not get trauma for the loss of their jobs. As Marchington (2012, p. 250) says, before retrenching employees, the management should confirm that there are no areas that these employees can fit when redeployed. In case such opportunities exist, the management should consider redeployment of these employees to ensure that there is motivation amongst the employees. It would be a kind gesture to the employees from the management that, although their fields have been rendered irrelevant within the firm, the management still appreciates their presence and would do everything within its powers to retain them in the firm. Gail Kelly should be clear on this.

Survival Syndrome

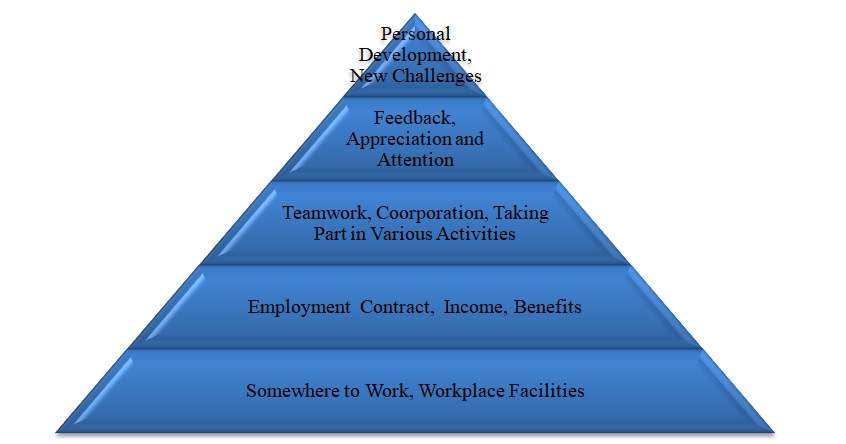

When a firm retrenches some of its employees, Halel (2000, p. 40) says that the remaining employees will develop some form of fear. They will feel that they lack job security, and this will have negative consequences on their performance within the firm. Hong and Faedda (1996, p. 500) say that this is what is referred to as survival syndrome. It is the feeling that employees who are retained after retrenchment develop. Staha (2006) explains that within a firm, there is always a hierarchy of needs of the employees. The pyramid below shows the hierarchy of needs for employees.

According to Stahl (2012, p. 72), employees’ needs differ as they develop in their careers and as they take time within the organization. The more they get established within the firm, the more their needs will rise as per the hierarchy given above. When an employee is jobless, he or she aspires to be in the first pyramid. At this stage, an employee just needs a place to work. They may not mind the working environment much, or the pay they are to earn. Once the employee gets this job, the needs will rise higher on the ladder. Such an employee would need a contract with the firm. He or she would start demanding higher pays (Price 2011, p. 29). When this is achieved, the next need will be teamwork, cooperation, and taking part in various activities within the firm. As one moves up, the need changes to the need for attention, appreciation and feedback.

Lastly, the need would move to personal development and new challenges.

Each level in the pyramid will define an employee. The first two levels are not always desirable in an organization. This is because these are individuals who do not have a clear focus in life, except for the need for a stable income. Their actions are, therefore, defined by the need to stay on job in order to continue earning. Most organizations desire to have employees in the third category and above (Pritchett 1985, p. 118). In the third category, the focus moves from personal needs to the need to ensure that the firm succeeds. Such employees are of great benefit to the organization as they will always commit themselves to achieve good results for the organization. The last two sections are always desirable for employees in managerial positions. Gail Kelly, the chief executive of Westpac Corporation should have the need to face new challenges. This will enable this firm to try new strategies that can help the firm reach its goals within a shorter time.

Survival syndrome always attacks this pyramid in the mind of the employee. During rightsizing, some of the employees who are believed to be invaluable to the firm are always retained. According to Cutcher (2007, p. 421), it would be expected that those employees who remain after a retrenchment process would be proud of themselves having been chosen amongst others. However, this is not always the case. Downsizing always affects these employees psychologically as they try to imagine what their fate would be in the future. They start thinking of how they would survive when their turn to be retrenched comes knocking. They get withdrawn as they turn for the inward consolation in case they get retrenched. This would lower their needs in the hierarchy from their current levels.

According to Evana (2011, p. 92), employees who are in need of teamwork and cooperation within the workplace will have their needs dropped to the last ladder in the pyramid. When they form groups within the organization, the focus of their discussion will no longer be on how they can work as a team to achieve the best benefits for the firm. Budhwar (2006, p. 512) says that their discussion will be on how they can get employed elsewhere so that they can resign from their current jobs before retrenchment. They look for survival mechanisms that will put them in a position where they have a fall-back plan.

This would seriously affect the operations of a firm. Upon merging Westpac Corporation and St. George Bank, the new firm was forced to conduct a rightsizing process before the firm could start operations. Some of the employees were retrenched as they became redundant to the firm. For the human resource manager of this new firm, the focus will not be on the compensation that the firm may need to pay the retrenched employees. As Hamill (2006, p. 33) says, the concern would be how to manage survival syndrome among the employees. Given that this is a merger, all the employees, irrespective of the firm they were working for before the merger, will feel insecure. They will develop the feeling that they can lose their jobs at any minute. Their needs within the firm will start dropping. In some cases, valuable employees would resign and get employed by competitors simply because they feel insecure.

Survival syndrome, if left unchecked, may have serious negative consequences for the firm. As Guthrie (2002, p. 188) says, it may result in a scenario where employees get completely disillusioned. When they watch their friends and workmates laid off, they feel that the firm has stopped caring for them. They will withdraw their dedication to the firm, partly because they try to be in solidarity with the retrenched employees, and partly because they feel that anything can happen, and their jobs can be lost. Brewster (2008, p. 40) advises that survival syndrome should be dealt with as soon as it arises. The human resource management of this new firm should ensure that employees’ needs are not lowered to undesirable levels after rightsizing.

Cultural Issues in Merger

According to Boselie (2005, p. 80), cultural issues will always arise in cases of mergers of two firms. Westpac Corporation was an independent firm whose operations were not in any way related to the operations of St. George Bank. In every firm, there is always organizational behavior that would define the culture of that organization. This means that the organizational culture that existed at Westpac Corporation will be different from that of St. George Bank. The organizational beliefs that defined the operations of Westpac Corporation will be unique to the employees of St. George Bank. However, the two units have been brought together, and the issue, in this case, is how to merge the two cultures.

Merging two cultures within a new organization can be very challenging (Huczynsky & Buchanan 2007, p. 98). This is despite the possibility of the two firms being in the same industry. For instance, Westpac Corporation and St. George Bank are both in the financial industry. However, the mission, vision, and values statements that always form the basis of a culture within an organization differ. While Westpac Corporation is a well-established bank, considered second in customer base and the volume of the assets, St. George Bank has just been elevated to the position of a bank. This means that while St. George Bank is aspiring to reach the levels that Westpac Corporation is, Westpac is striving to be the regional giant in this industry. Each of the banks’ visions defines its culture, a culture that employees must learn and embrace in all the activities they undertake. However, the new management has to come up with a strategy of developing a new culture within the new setting. When Westpac Corporation and St. George Bank merged to form a larger financial unit, both firms’ vision, mission, and values had to change. This is because they were experiencing a sudden increase in asset base and market coverage that they had not anticipated in a near future. Changing these statements will help change the overall culture of the organization (Biswas 2011, p. 99).

According to Baruch (2008, p. 430), changing the overall culture of the organization helps the firm in the smooth implementation of policies. First, it creates an equal platform where all the employees would need to learn the new culture. The former employees of Westpac Corporation and St. George Bank Will have to embrace an environment with a new culture, unknown to any of them. This would make them believe that this is a new environment, new to everyone, and one that needs all to adjust. This is better than having the culture of either of the firms implemented in the new firm. This is because there might be some discontent on one side, and content that nears laziness combined with pride on the other side (Cardel 1998, p. 39). The group whose culture shall be retained will feel superior and would lack the urge to know beyond their current knowledge. This will massively reduce their performance within this new firm. On the other hand, the group whose culture was ignored will feel despised. Instead of learning the new culture presented to them, they will develop hatred towards it, always associating it to the other firm before the merger took place. Such cases may also worsen to an extent that they lead to rifts within the organization. In such instances, instead of employees working together in a culture set to help the firm achieve its goals, employees will be using this culture as the basis of their disagreements (Arthur 2008, p. 680).

Developing a completely new culture will help this firm achieve its objectives as it will bring the employees together. It will make them feel that they share the same goals, and will share the same challenge in learning the new culture. As they struggle to learn this new culture presented to them, they will help each other and this will unify them (Okumu 2013, p. 117). They will forget the fact that they were employees of different organizations. This will have a positive impact on the new firm created out of the merger of the two firms

List of References

Arthur, J 2008, Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover, The academy of management journal, vol. 37, no. 3, p. 670-687.

Aswathappa, K 2005, Human resource and personnel management: Text and cases, Tata McGraw-Hill, New Delhi.

Barney, J 2010, Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage, Journal of management, vol. 17, no.1, pp. 99.

Baruch, Y 2008, Response rate in academic studies-A comparative analysis, Human relations, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 421-438.

Biswas, S 2011, Commitment, involvement, and satisfaction as predictors of employee performance, South Asian Journal of Management, vol. 18 no. 2, pp. 92-107.

Boselie, P 2005, Commonalities and contradictions in HRM and performance research, Human Resource Management Journal, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 67-94.

Brewster, C 2008, A continent of diversity, Personnel management London, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 36-40.

Budhwar, P 2006, Rethinking comparative and cross-national human resource management research, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 497-515.

Buono, A 2003, The human side of mergers and acquisitions: Managing collisions between people, cultures, and organizations, Beard Books, Washington.

Cardel, G 1998, Cultural dimensions of international mergers and acquisitions, Gruyter, Berlin.

Cutcher, G 2007, Impact on Economic Performance of a Transformation in Workplace Relations, Management Journal, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 241.

Dowling, P 2008, International human resource management: Managing people in a multinational context, Thomson Learning, London.

Drake, A & Salter, S 2007, Empowerment, motivation, and performance: examining the impact of feedback and incentives on non management employees, Behavioral Research in Accounting, vol. 2 no. 3, pp. 1971-1989.

Evana, P 2011, The global challenge: international human resource management, McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York.

Fey, C 2012, The effect of human resource management practices on MNC subsidiary performance in Russia, Journal of International Business Studies, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 59-75.

Grobler, P 2006, Human resource management in South Africa, Thomson Learning, London.

Guesa, E 2001, Human resource management and industrial relations, Journal of management Studies, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 503-521.

Guest, D 2009, Human resource management and performance: a review and research agenda, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 263-276.

Guthrie, J 2002, High-involvement work practices, turnover, and productivity: Evidence from New Zealand The Academy of Management Journal, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 180-190.

Hacker, S & Tammy, R 2004, Transformational Leadership: Creating Organization of Meaning. Milwaukee, Quality Press, Wisconsin.

Halel, W 2000, Facing freedom, Executive Excellence, vol. 17 no. 3, pp. 13-42.

Hamill, J 2006, Labour relations decision making within multinational corporations, Industrial Relations Journal, vol. 15, no. 2, pp. 30-34.

Hedlund, G 2004, The hypermodern MNC—a hierarchy, Human resource management, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 9-35.

Hong, S & Faedda, S 1996, Refinement of the Hong psychological reactance scale, Community College Review, vol. 4 no. 3, pp. 65-138.

Huczynsky, A, & Buchanan, D 2007, Organisational Behaviour: An Introductory Text, Pitman, London.

Huy, Q 2002, Emotional filtering in strategic change, Academy of Management Proceedings, vol. 6 no. 1, pp. 43-78.

Jacksona, S1992, Diversity in the workplace: Human resources initiatives, Guilford Press, New York.

Jensen, T 2011, The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance, Academy of management journal, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 635-672.

Kandula, S 2009, Strategic human resource development, PHI Learning Pvt Ltd, New Delhi.

Klein, J 2003, An HR guide to mergers and acquisitions in Europe, Gower, New York.

Kotter, J 1990, A Force For Change, Free Press, New York.

Kouzes, J & Posner, B 2002, The Leadership Challenge, Jossey-Bass, San Fransico.

Marchington, M 2012, Involvement and participation, Human Resource Management: A Critical Text, vol. 7, no. 67, pp. 280-305.

Okumu, C 2013, Strategic human resource development, Wiley, New Jersey.

Pielstick, D 1998, The Transforming Leader, a Meta-Ethnographic Analysis, The Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 71 no. 1, pp. 500-507.

Pikula, C. 1999, Mergers and acquisitions: Organizational culture & HR issues, IRC Press, Kingston.

Price, A 2011, Human resource management, Cengage Learning EMEA, Andover.

Pritchett, P 1985, After the merger: Managing the shockwaves, Dow Jones-Irwin Homewood.

Rees, C 2003, HR’s Contribution to International Mergers and Acquisitions, Cengage, Wimbledon.

Regis, R 2008, Strategic human resource management and development Excel Books, New Delhi.

Rollinson, D 2005, Organisational Behaviour and Analysis: An Integrated Approach, Prentice Hall, New York.

Staha, G 2006, Handbook of research in international human resource management, Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham.

Stahl, G 2012, Handbook of research in international human resource management, Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham.

Stahla, G 2005, Mergers and acquisitions: Managing culture and human resources, Stanford Business Books, Stanford.

Wilson, J 2005, Human resource development: Learning & training for individuals & organizations, Kogan Page, London.

Yukl, G 2010, Leadership in Organisations, Prentice Hall, New Jersey.