Introduction

Managing risk has become a central concept in all organizations. It is worth noting that there is a guarantee that there will be no risks as a company or industry goes about its daily activities. In the construction industry, it is important to ensure that the project goes smoothly since if it does not, than various interested stakeholders will be disappointed. Ideally, it is of a paramount significance for the construction industry to identify risks, understand them and draw a plan that is aimed at minimizing the identified risks1. Managing risks entails a systematic process which helps professional in the construction industry to manage and comprehend uncertainties. Various scholars have defined risk differently, for the purposes of this task, risk will be defined as all events, occurrences, as well as actions that prevent or hinder successful attainment of goals, as well as plans in the construction industry. There are those who believe that it is a waste to invest time and resource in developing risk management models, however, if the project faces risks, then the consequences will be too harsh to deal with and it is only rational to have a model in place that can help the industry successfully implement its plans and attain its preset goals.

Scholars have noted that the majority of projects, including those in the construction industry, take place in an environment characterized by ever changing environment having several pitfalls which might negatively impact the project’s outcomes. Additionally, it has been established that high rate of project failure is attributed to the fact that the responsible parties are not taking into account measures that may help in evaluating and handling risks.

The objective of risk management is to point out all possible risks to a project. Issues included are frequency of risk occurrence, degree of impact among others. This ultimately helps in reducing losses. The main task of this paper is to develop a risk model for the execution of construction in public housing projects in Trinidad and Tobago. There is a need to have in place a model that will help the primary stakeholders in these sector to minimize risk and ensure proper constructions of houses2 3 4.

Literature review

All these models have divided risk management into phases. In most cases these phases are risk identification, risk evaluation, risk control and risk monitoring. It is important to point out that risk identification is where the construction team or the leader of any project takes time and identifies all the threats facing the project at hand5. These risks can be categorized as follows, strategic, operational, legal, regulatory and financial risks. At the second stage (evaluation) the list of all the possible threats based on their probability and severity is produced. This is followed by risk control which encompasses the best option to be executed in order to control the identified risks. Among the steps that can be taken at this stage are avoiding, reducing or transferring the risk. The last phase entails the review of the industry’s capabilities to successfully address any interruption that might occur when implementing the project, among other things pertaining to managing risk6.

Another model divides risk management into six phases beginning with risk identification, risk recognition, analysis phase which entails converting risk data into suitable information, planning phase where the information is made acted upon, tracking phase where the risk is monitored, as well as actions being executed to curb the identified risks. The fifth phase is control which is aimed at correcting any sort of deviation from the initial plan, and lastly risk communication where the project team stresses on issues related to the project risks7.

Another model classifies the risk management phases into four categories. The first is risk identification where the team seek to locate and point out possible risks, risk analysis then follows this and involves consolidating and classifying the identified risks. The third phase (risk control planning) encompasses the activity of selecting the most sever risks to be dealt with. The last phase is where the team observes the situation after the risks has been addressed. There are those who have developed a three step risk management model8. The steps include risk identification where a list of all possible risks is developed attained when members brainstorm, followed by risk analysis where the team will eventually decide if certain risks are worth migrating to or not and the last step is to prioritize and map risks to determine the severity of the risks identified and analyzed based on their impact by coming up with strategies to prevent occurrence of the risks 9 10.

From all the covered models, it is evident that risk management entails a series of steps that should be strictly followed. There have been recent proposals that goal setting and education should be incorporated in risk management. This will form a part of the model to be developed.

The proposed model

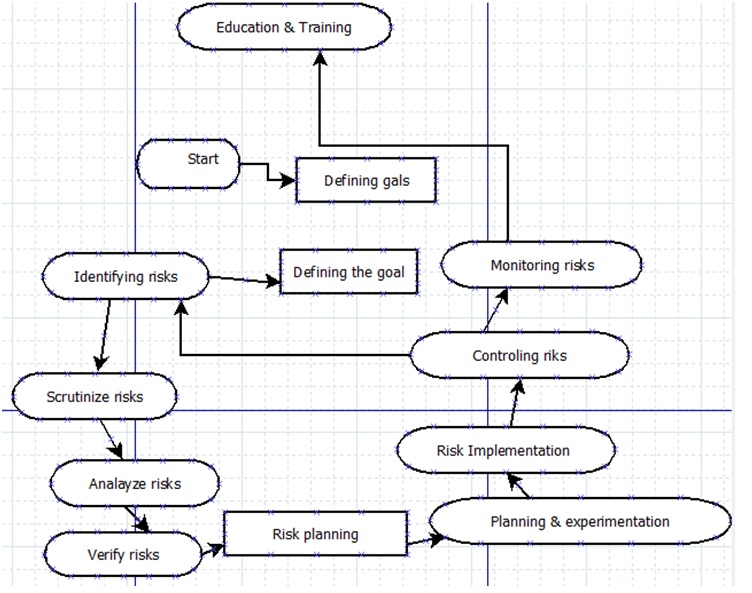

It is worth noting that the construction industry has projects that are very complex. This calls for a risk management model. Building from the previously studied model, a unique risk management which entails the need for having risk management, defining goals, identifying the risks, scrutinizing the risks, analyzing the risk, verifying the risks, planning for the risks, planning experiment, implementing the risks, controlling the risks, monitoring the risks and finally carrying out education and training11 12 13.

For the construction industry, it is necessary to have a risk management model which will help reduce the risk which leads to serious losses. The first step that the industry in the country should implement is to clearly define the significance of risk management to the various interested parties in order to successfully identify possible risks associated with the construction industry14. At this point, it is very important to include all the relevant and primary stakeholders so that not only the risks are identified but also better mitigation strategies are developed. It is worth noting that this will help the industry if construction to be in a better position in identifying goals for implementing the model15 16.

The next step is to define and review the goals. This entails the mission and vision of the sector. Additionally, issues related to challenges, as well as goals are explicitly developed. This is followed by defining the strategy so that it would be possible to come up with clear objectives, expected outcomes and challenges.

In order to manage risks, it is paramount to identify them. The process entails all the activities, including brain storming, that identify the potential risk to the construction of houses in the country. When identifying risks, there is a need to have a base from where one can benchmark the probability of risk occurrence. At this point, there is a need to develop a list of all the identified risks. It has also been suggested that there is a need to continuously implement this phase throughout the project life cycle so that those risks not earlier identified could be documented and dealt with accordingly. The methods to be used include brainstorming, interviewing stakeholders, use customer complaints, questionnaires etc.17 18.

Scrutinizing the risk is the fourth phase. This is where all those risks identified in the previous phases, the purpose is to critically evaluate each of them and do away with those that are not linked to the project or do not have any impact during construction19.

The next step is the analysis of the risks. The collected data should facilitate decision making. During this stage the following should be done; describing the probability of risk occurring, documenting the impact of the risks if they occur, displaying the extent of loss in order to establish the risks disclosure so that it is possible to list all risks as well as threats20 21 22. Those risks which have higher probability of occurrence and high impact must be dealt with as soon as possible. Ideally, the issue here is to prioritize the identified risks.

As suggested by Molenaar, 2005; O’Connor, et al., 1993 and Pennock & Haimes, 2001 verifying the risk entails efforts directed towards establishing the relevance of the risks and threats identified23 24 25. The main objective is to do away with the risks that do not threaten the attainment of the project objectives and goals. Risk planning is where the risk information is converted into action aimed at coming up with actions to address every risk, prioritizing on the measures to be taken and coming up with a master plan on how to deal with the issue. All these will help the industry to reduce the likelihood of risk occurrence and the loss associated with it. The team needs to follow simple rules, process control, testing, modeling and inheritance26.

Planning and experimenting entails efforts directed towards testing if the strategies adopted in the previous phase were accurate and effective. Additionally, this stage tries to evaluate if all the risks are directly linked to the project and whether they are correctly classified on the basis of their effects and probability of occurrence. The objective of this phase is to ensure that resources are used effectively.

According to Skorupka, 2008; Wallbaum, Sabrina, Rolf, 2011; HyunSeok, KyuMan, TaeHoon, & ChangTaek, 2011 and Kumaraswamy, 1997 , risk implementation is where the plans developed are put into action27 28 29 30. The time line and responsibility of members to oversee each task is made available and documented. The three options that can be followed include avoiding, reducing or transferring the risks. The stage of risk control gives an update on the entire project phase. A report about the entire execution process is developed. Monitoring the risk encompasses observing the risk status as well as the action and providing a real time monitoring to change the risk execution process so that it is possible to have an update on the process. This phase ensures that there is an effective implementation of action plan developed. The last stage is education and training. It is later used to educate and train other workers in the related industry. This is important as it equips the stakeholders with prior knowledge on the risk in the construction industry.

Bibliography

Alnuaimi, A. et al. “Causes, Effects, Benefits, and Remedies of Change Orders on Public Construction Projects in Oman.” Journal Of Construction Engineering & Management 136 no. 5 (2010): 615-622.

Ashuri, Baabak & L. Jian. “Time Series Analysis of ENR Construction Cost Index.” Journal Of Construction Engineering & Management 136 no. 11 (2010): 1227-1237.

Beach, R. et al. “An evaluation of partnership development in the construction industry”, International journal of project management, no. 23 (2005): 611.

Chapaman, Chris & Stephen Wards. “Why risk efficiency is key aspect of best practice project,” International Journal of Project Management, 22, no. 8 (2004): 619-632.

Chapaman, Chris. Managing project risks and uncertainty. Chester: John Wiley & Sons, 2002.

Chapman, R. “The controlling influences on effective risk identification and assessment for construction design management”, International Journal of Project management, 19 no. (3) (2001): 147-160.

Cohen, M. & G. Palmer. Project risk identification and management, AACE International Transaction, 2004.

Del Cano, A.D. & M.P.De la Cruz. “Integrated Methodology for Project Risk Management”, Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 128 no. 6 (2002): 473-485.

Diekmann, J. et al. Procedural and Computational Studies for Cost Risk Analysis of DOE Hazardous Waste Remediation Project. Technical Report to Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL, 1995.

Diekmann, J. Procedure for Cost Risk Analysis. Technical Manual, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Office of the Chief Engineer, Washington, DC. 1994.

Dubois, Anna & Lars-Erik Gaddle. The construction industry as loosely coupled system: Implication for productivity and innovatively. Paper for the 17th IMP Conference, 9th-11th September 2001, Oslo, Norway, 2001.

Eom, S. et al. “Risk Index Model for Minimizing Environmental Disputes in Construction.” Journal Of Construction Engineering & Management, 135 no. 1 (2009): 34-41.

Erikssom, P. Procurement and governance of construction project: A theoretical model based on transaction cost economies. Lulea Univeristy of Technology, 2003a.

Eriksson, P. Long-term relationship between parties in constriction project: A way to increase competitive advantage, Lulea University of Technology, 2003b.

Fenelle, Cheryl. “Partnership: Mirage or reality?” Risk management, 43 no. 5 (1996): 55.

Floricel, Serghei & Roger Miller. “Strategizing for anticipated risk and turbulence in large-scale engineering projects”, International journal of Project Management, 19 (2001): 445-455.

Ford, D. et al. “Aeal option to valuing strategic flexibility in uncertain construction projects”, Construction Management and Economics,, 20 (2002): 343-351.

Grey, S. Practical Risk Assessment for Project Managers. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons, (1995).

Haimes, Yacov Y. “Principles and Guidelines for Project Risk Management,” Systems Engineering, 5 no. 2 (2001): 89-108.

Haimes, Yacov Y.. “Principles and Guidelines for Project Risk Management,” Systems Engineering, 5 no. 2 (2001): 89-108.

Hallikas, J., et al. “Risk management process in supplier networks”, International Journal of Production Economics, 90 (2004): 47-58.

Hartman, F. & Snelgrove, P. “Risk Allocation in Lump-sum Contracts-Concept of Latent Dispute”, ASCE Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 122 no.3 (1996): 291-296.

Hastak, M. & Baim, E. “Risk Factors Affecting Management and Maintenance Cost of Urban Infrastructure”, Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 7 no. 2 (2001): 67-76.

Hecht, H. & Niemeier, D. “Too Cautious? Avoiding Risk in Transportation Project Development”, Journal of Infrastructure Systems, 8 no. 1 (2002): 20-28.

Hyun Seok, Moon. “Selection Model for Delivery Methods for Multifamily-Housing Construction Projects.” Journal Of Management In Engineering, 27 no. 2 (2011): 106-115.

HyunSeok, Moon, KyuMan Cho, TaeHoon Hong, ChangTaek Hyun. “Selection Model for Delivery Methods for Multifamily-Housing Construction Projects”. Journal Of Management In Engineering, 27 no. 2 (2011): 106-115.

Kumaraswamy, M. “Appropriate Appraisal and Apportionment of Megaproject Risks”, Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 123 no. 2 (1997): 51-56.

Leslie, Edwards. Practical Risk Management in the Construction Industry, New York: Thomas Telford, 1995.

Love, Peter E. D. et al. “Divergence or Congruence? A Path Model of Rework for Building and Civil Engineering Projects.” Journal Of Performance Of Constructed Facilities 23 no. 6 (2009): 480-488.

Mehndiratta, Shomik Raj, Daniel Brand, Thomas E. “Parody How Transportation Planners and Decision Makers Address Risk and Uncertainty”, Transportation Research Board, 17 (2000): 46-53.

Molenaar, Keith R. “Programmatic Cost Risk Analysis for Highway Mega-Projects,” ASCE Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 131 no. 3 (2005): 343-353.

O’Connor, et al. “Analysis of Highway Project Construction Claims,” Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 7 no. 3 (1993): 170-180.

Project Management Institute. A Guide to Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2004.

Robert, E. Introduction to Risk Analysis, London: Penn Well Publishing Company, 1984.

Sae-Hyun, J., Moonseo, P. & Hyun-Soo, L. “Cost estimation model for building projects using case-based reasoning”, Canadian Journal Of Civil Engineering 38 no. 5 (2011): 570-581.

Skorupka, Dariusz. “Identification and Initial Risk Assessment of Construction Projects in Poland.” Journal Of Management In Engineering, 24 no. 3 (2008): 120-127.

Smith, R. “Risk Identification and Allocation: Saving Money by Improving Contracting and Contracting Practices”, The International Construction Law Review, (1995): 40-71.

Thal, E. Jason J. & White, D. “Estimation of Cost Contingency for Air Force Construction Projects.” Journal Of Construction Engineering & Management, 136 no. 11 (2010): 1181-1188.

Vijay, Kanabara. Project Risk Management: A Step-by-Step Guide to Reducing Project Risk, Copley Publishing Group, 1997.

Wallbaum, Holger, Sabrina Krank, Rolf Teloh. “Prioritizing Sustainability Criteria in Urban Planning Processes: Methodology Application,” Journal Of Urban Planning & Development 137, no1 (2011): 20-28.

Wideman, R. Max. Project and Program Risk Management: A Guide to Managing Project Risks and Opportunities. Newton Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 1992.

Footnotes

- Kanabara Vijay. Project Risk Management: A Step-by-Step Guide to Reducing Project Risk, (Copley Publishing Group, 1997).

- R. Beach. et al. “An evaluation of partnership development in the construction industry”, International journal of project management, no. 23 (2005): 611.

- Chris Chapaman & Stephen Wards. “Why risk efficiency is key aspect of best practice project,” International Journal of Project Management, 22, no. 8 (2004): 619-632.

- Holger Wallbaum, Sabrina Krank, Rolf Teloh. “Prioritizing Sustainability Criteria in Urban Planning Processes: Methodology Application,” Journal Of Urban Planning & Development 137, no1 (2011): 20-28.

- Project Management Institute. A Guide to Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). (Newton Square, PA: Project Management Institute, 2004)

- E. Robert. Introduction to Risk Analysis, (London: Penn Well Publishing Company, 1984).

- Kanabar Vijay. Project Risk Management: A Step-by-Step Guide to Reducing Project Risk, (Copley Publishing Group, 1997).

- ibid.

- Chris Chapman & Stephen Ward. Managing project risks and uncertainty. (Chester: John Wiley & Sons, 2002).

- Robert J. Chapman. “The controlling influences on effective risk identification and assessment for construction design management”, International Journal of Project Management, 19 no. 3, (2001): 147-160.

- M. Cohen & G. Palmer. Project risk identification and management, AACE International Transaction, 2004).

- J. Diekmann. Procedure for Cost Risk Analysis. Technical Manual, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Office of the Chief Engineer, Washington, DC. 1994.

- Anna Dubois & Lars-Erik Gaddle. The construction industry as loosely coupled system: Implication for productivity and innovatively. Paper for the 17th IMP Conference, 9th-11th September 2001, Oslo, Norway, 2001.

- P. Erikssom. Procurement and governance of construction project: A theoretical model based on transaction cost economies. (Lulea Univeristy of Technology, 2003a).

- Cheryl Fenelle. “Partnership: Mirage or reality?” Risk management, 43 no. 5 (1996): 55.

- Serghei Floricel & Roger Miller. “Strategizing for anticipated risk and turbulence in large-scale engineering projects”, International journal of Project Management, 19 (2001): 445-455.

- Moon Hyun Seok. “Selection Model for Delivery Methods for Multifamily-Housing Construction Projects.” Journal Of Management In Engineering, 27 no. 2 (2011): 106-115.

- Alfred E. Thal, Jr., Jason J. Cook, and Edward D. White. “Estimation of Cost Contingency for Air Force Construction Projects.” Journal Of Construction Engineering & Management, 136 no. 11 (2010): 1181-1188.

- Edwards Leslie. Practical Risk Management in the Construction Industry, (New York: Thomas Telford, 1995).

- Baabak Ashuri & L. Jian. “Time Series Analysis of ENR Construction Cost Index.” Journal Of Construction Engineering & Management 136 no. 11 (2010): 1227-1237.

- Peter E. D. Love. et al. “Divergence or Congruence? A Path Model of Rework for Building and Civil Engineering Projects.” Journal Of Performance Of Constructed Facilities 23 no. 6 (2009): 480-488.

- Shomik Raj Mehndiratta, Daniel Brand, Thomas E. “Parody How Transportation Planners and Decision Makers Address Risk and Uncertainty”, Transportation Research Board, 17 (2000): 46-53.

- Keith R. Molenaar. “Programmatic Cost Risk Analysis for Highway Mega-Projects,” ASCE Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 131 no. 3 (2005): 343-353.

- O’Connor, et al. “Analysis of Highway Project Construction Claims,” Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 7 no. 3 (1993): 170-180.

- Yacov Y. Haimes. “Principles and Guidelines for Project Risk Management,” Systems Engineering, 5 no. 2 (2001): 89-108.

- R. Max Wideman. Project and Program Risk Management: A Guide to Managing Project Risks and Opportunities. Newton Square, PA.: Project Management Institute, 1992.

- Dariusz Skorupka. “Identification and Initial Risk Assessment of Construction Projects in Poland.” Journal Of Management In Engineering, 24 no. 3 (2008): 120-127.

- Holger Wallbaum, Sabrina Krank, Rolf Teloh. “Prioritizing Sustainability Criteria in Urban Planning Processes: Methodology Application”, Journal Of Urban Planning & Development, 137 no. 1 (2011): 20-28.

- Moon HyunSeok, KyuMan Cho, TaeHoon Hong, ChangTaek Hyun. “Selection Model for Delivery Methods for Multifamily-Housing Construction Projects”. Journal Of Management In Engineering, 27 no. 2 (2011): 106-115.

- M. Kumaraswamy “Appropriate Appraisal and Apportionment of Megaproject Risks”, Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, 123 no. 2 (1997): 51-56.