Entry Vignette

Should not doing business with the federal government follow the same paradigm as applying for a job position? The need is identified, advertised and those interested apply. The company that best meets the criteria gets the contract, provides the supplies or services and the government pays the bill. Is this, not the ideal we expect? Is this not what we as Americans would call a fair chance? This is my idea of a fair chance. What would I have to do to become a federal contractor or subcontractor?

What about the assistance programs for the small business person? How do these affect my idea of a ‘fair chance’? Didn’t the government create these programs to help put us all on an even playing field?

What about the global small business person who is looking for that fair chance outside of the United States boundaries and territories? It is common knowledge that the US government does business afar, globally. Are those who are global US Citizens with a product or service to sell the government afforded the same opportunities as those in the states? What difference does it make if my store front is located in California, New Jersey or Portugal? I am still a US Citizen and paying taxes to the US Government. Why couldn’t I be a US Small business owner living globally?

In this case I will examine how these questions effect developing a course of action that might allow me to become a federal contractor or subcontractor. Furthermore, I will further explain why these questions stand apart, what makes these ‘key’ questions in my particular case.

Issue identification, purpose and method of study

- Project Title

- Becoming a Federal Subcontractor: A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA)

- Project Description

- Using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) strategies, develop and choose the best course of action that will allow me to become a federal subcontractor.

- Project Rationale

This project represents a personal entrepreneurial interest. I am ready to make a career decision and feel federal subcontracting could be an option given my work experience, observations, formal education, and goals.

During my 13 years as a federal employee in the information technology area, I observed the work of approximately 20 contractors and subcontractors over eight years. These individuals represented small, less publicly known companies, as well as large publicly known companies such as Oracle, Bay Networks, Unisys, and Microsoft. Approximately 35% of the personnel served as weeklong instructors, teaching topics such as operating systems, data communications, design patterns, and programming languages. In addition, approximately 3% performed consulting services and 62% performed software and hardware installations.

In 90% of the cases observed, on the scheduled workday, the individuals showed up in our department, we provided them the access to the resources necessary for the task, and they remained alone to complete the job. After the task was completed, the individuals left the facility. In most of the cases, my colleagues and I did not feel the final product met our expectations; however, we did not pursue action to rectify the situation through our procurement office. I asked the last Microsoft subcontractor for his thoughts on this matter. He indicated the contract specifications were vague, hence, making it difficult to indicate what part of the contract was not complete. Is this a common occurrence in government proposals? Are vague specifications something companies look for when determining which solicitations to answer?

The lifestyle of a subcontractor seems like the perfect scenario to me. They are self-employed, they only bid for jobs in which they are interested, and each job has a definite ending. These few examples comprise a subset of my vision of success and, subsequently, my goals (Bacon & Mears, 2008).

I completed my Computer Science degree in 1995. Between 1995 and 2005, I attended more than 18 technical courses taught by companies such as Oracle, Sun Microsystems, Apple, and Industrial Logic. In one year alone, the federal entity for which I worked invested over $34,000 in education expenses. I am striving to keep up my education by pursuing a master’s degree in Information Systems through Aspen University. Besides working in the United States, I have lived and worked in a multi-national environment. I have had the opportunity to observe and use some of the technology available in East Timor, Laos, Cambodia, India, Thailand, and Kosovo. I found that the Internet access was expensive, unreliable, and not readily available. This experience has given me the tools to evaluate what is required if I would like to bid on federal contracting jobs in a developing countries.

Personal / Professional Expectations

At the conclusion of the project, I will select a course of action that will allow me to feel confident towards entering the workforce as a federal subcontractor while maintaining the quality of life and a sense of economic security.

Project Goals

The main goal is to choose the best course of action from at least three possible options. This project requires research (or the gathering of facts), validating assumptions, and documenting definitions, as well as developing and evaluating a set of alternatives. Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) is a methodology designed to assist in choosing the best method.

The first multi-facetted question that requires an answer is: “How does a small business owner find out about, and apply for, subcontracting opportunities in the Internet Technology area?” The result of this question will form the collection of facts, assumptions, and definitions applicable in the MCDM process.

Subsequent questions are introspective. These are: “How can I make this a viable career option for me?” and “What sacrifices am I willing to make?” Bacon and Mears (2008, p. 14) present questions and exercises designed to assist in this process.

Research

I attribute my initial interest in this topic to my past observations while in service with the federal government. Interpersonal communication and circumstance have further peaked my interest. I lived in Kosovo for one year and then for one and a half years in East Timor. Through conversations with other people, I believe the possibility for federal contracting opportunities are worldwide. In East Timor, I met a Land of Lakes contractor, who was awarded a contract from U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). While serving in Kosovo at the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Joint Headquarters, I spoke with a U.S. Air Force Lieutenant Colonel about opportunities in the Azores. When not deployed, he was stationed at the U.S. Air Force base on Terceira Island in the medical procurement detachment. In his experience and understanding of federal procurement rules, if a small, minority-owned business responded to a solicitation request and even if its offer was not the lowest bid, that business often had the best chance to obtain the contract. If this person accurately translated federal procurement regulations at the contractor level, then I won’t know if there are any such federal procurement guidelines specifically addressing federal subcontractors. Is there rules to help stimulate business for the small, minority, veteran, business subcontractor, too? Also, while I was in Kosovo, I visited Camp Bondsteel, the U.S. Army controlled, multinational brigade base in the south of Kosovo. Kellogg, Brown, and Root (KBR) held the federal contract for the maintenance, security, and food services. Is it possible that KBR employed subcontractors in Kosovo? Assuming federal contracting opportunities exist, then are there overseas opportunities for the federal subcontractor also? Proving or disproving these questions will help me understand the scope of the situation. Furthermore, the answers will provide input into the MCDM criterion development process. Worldwide federal subcontracting opportunities may be an advantage in my situation; my spouse is a Portuguese military officer and not a permanent U.S. resident. I do not know what our next location will be, once his current assignment is complete. The degree to which I may consider worldwide federal subcontracting opportunities will depend upon his next assignment.

Federal procurement rules offering opportunities for the veteran-owned, small, minority business might play a significant factor in choosing a course of action, as I will be in this category. On August 21, 2008, and Internet posting was titled “The Veterans Affairs Department wants to put companies owned by veterans at the top of the pecking order for agency contracting opportunities” (Brodsky, 2008) caught my attention. Could this be an advantage in my situation, or does this only apply to contractors? Does the possibility exist for a business to classify itself as both a federal contractor and federal subcontractor? What is the difference between the opportunities available to a federal contractor versus a federal subcontractor in Internet Technology? Answers to these questions will help to document the facts, assumptions, definitions, and criterion development of my MCDM analysis.

Non-profit organizations such as the Small Business Administration (SBA), SCORE, the Association of Procurement Technical Assistance Center (APTAC), and the Center for Veterans Enterprise (CVE) advertise assistance for the small businessperson on the Internet. The CVE Web site indicates the organization “maintains a set of robust Outreach programs for veterans.” I intend to investigate what these programs have to offer, and solicit advice and assistance from these non-profit organizations. If possible, I would like to attend a scheduled seminar or conference hosted by one of these organizations. Furthermore, I would hope to discover more organizations like these during my research.

Companies such as Onvia promise help to individuals to find contracts. Is this information applicable to the subcontractor? What is other profit-making companies offer the same services? Are these companies selling information that is provided free of cost from another provider? What do these services cost? In The Boss of You, Bacon and Mears (2008, pp. 17-18) provide helpful information for the new, small businessperson when he or she is starting a business. One of these items is that some tasks might be worth identifying and delegating to someone else (Bacon & Mears, 2008, pp. 17-18). I intend to use the advice and other information in the book when I develop the introspective questions.

Through my work experience, I am vaguely familiar with the term “Request for Proposal” (RFP). This term and process deserve further investigation. Some companies offer help to develop responses to an RFP, along with sales of templates. Do I need to know this as a subcontractor or does it only applies to contractors? Is it necessary to use these companies or are there other methods to answer an RFP?

A U.S. citizen must file taxes regardless of where that person resides. What are the tax implications of being self-employed? The Website advertises technology vacancies. The advanced search criteria include the following “employment type”:

- Contract – Corp to Corp

- Contract – Independent

- Contract – W2

- Contract to Hire – Corp to Corp

- Contract to Hire – Independent

- Contract to Hire – W2

The selection list contains the term “contract,” but what exactly does this mean and is this relevant in this instance? If it is relevant, then these categories may be added to the MCDM criterion. During my research, I expect to find the answers to these questions.

The preceding paragraphs represent a sampling of the questions the proposed project will raise, indicate my preliminary research sources used to formulate the questions and describe potential criterion for the MCDM analysis. The actual use of the answers is dependent upon the content of the questions and relevance to the main research question.

I spent a total of twelve years working for the federal government and twenty three years as a member of the Army National Guard. The conditions of employment entailed a regulatory symbiotic relationship. In my particular instance in order to keep my federal job I was required to maintain my membership in the Army National Guard. Every day I would wear my uniform to work even though I was paid as a civil servant. One weekend out of the month and two weeks out of the year, I would wear the uniform and be paid as a military member. Precisely why this requirement exists I still do not know.

After my first nine years I felt I hit what some might call “the glass ceiling”. In my case two glass ceilings existed. The first was the reluctance of senior non-commissioned (NCO) military male members to promote females to the same levels as I observed year after year. The second, on the weekday side, was the reluctance of the officers to promote any NCO to the civil service grades that are typically held in parallel for commissioned officers. For example at this time a GS-8 normally was associated with the military rank of first lieutenant. To see an individual wearing the rank of a Staff sergeant and yet, paid as a GS-8 was fairly unusual in 1988. This was my precise case in 1989. Having many years left I felt my only option was to obtain a degree and become a commissioned officer. In 1995 I graduated with a degree in Computer Science and obtained my commission.

Shortly, after I went back to work for the same organization but this time as a GS-11 and with the glass ceilings removed from in my perception of the situation. I enjoyed my work and was very eager to help the organization advance. We were moving away from the 1970’s mainframes and toward newer technology. The organization rewarded my efforts and encouraged those efforts by sending me to many technical courses instructed by top companies such as Oracle, Sun, Apple and HP. What I was unaware of, is that the organization was about to changing in respect to technological plans and policies. Those changes had just not filtered down yet. I did not understand the delicate balance between the civilian world and the government world when it comes to occupations.. The government should not try to replicate occupations that can be done by civilians. This philosophy helps businesses because the government is a huge buyer of goods and services. Unfortuntely, in my case this philosophy and reflected changes in IT policy and my position almost overnight changed from one who implements new technology into project management.

I watched, sat next to and assisted many of contractors and subcontractors over the next five years. I felt envious that they were given the opportunity to do the tasks I felt I should be doing. In many cases I felt that I knew more about the technology the contractors and subcontractors were attempting to implement then they did. I made a mistake by not asking more questions geared toward the process they went through to get their jobs. At the time I felt it was rude to ask such questions. Today, we call this networking and it is an important part of one’s career.

As the second Gulf Conflict came about the Army National Guard began to deploy more and more troops. Eventually the slogan around the office became “Everyone is going to go sooner or later.” Most people did not want to go and leave their homes for a year or more. Particularly, those who thought they were only ‘part-time’ soldiers. In my case and those in the same situation the weekend job began to overshadow our weekday job. The threat of being mobilized grew closer each week and I helped the contractors and subcontractors mine through the personnel data looking for candidates. Together, we developed a local system that could forecast years in advance those who would be eligible for subsequent mobilization rotations. Working on and employing the web services technology brought back that job satisfaction I thought I had lost. Along with the satisfaction came the realization that I had just help to establish a system that would take soldiers away from their families. Many of these soldiers were once under my command. I knew their names and their families. Had I just helped to rip apart other people’s families? In my desire for technology had I just crossed an ethical line? I doubt any of the contractors or subcontractors felt the same sense of guilt.

Could government contracting or subcontracting be the prefect solution? I would no longer have the requirement to maintain a membership in the Army National Guard. Maybe, through contracting or subcontracting I might be allowed to focus on a specific job without regard the worry of how the organizations policies toward IT might be changing. I had always heard there were supposed to be breaks for small businesses owned by women. Maybe, there is some truth in this or some other programs that could help someone like me to find out about, apply for and possibly win some of these government contracts.

Before I could investigate the possibility further I would first take “my turn” and serve one year at the NATO HQ in Kosovo as part of the efforts to stop war on terrorism. After returning I found many people who were unaware of exactly where the US has soldiers located as part of these efforts. I did return and still I have the same pending question, “What course of action would I have to take to become a federal contractor and/or subcontractor?”

The investigation and development such courses of action would get a little more complicated then when I initially posed the question to myself. My world changed that year I was away in ways I never could have imagined. This was the first time I ever worked with people from different countries on a daily basis. I came to appreciate working in such an environment. If I thought it was realistic I would make working in a multicultural environment part of my decision criterion.

I also met a Portuguese Officer named Jorge. Two years later Jorge and I would marry. He is not nor at this time does he intend to become a US citizen. Further, he still has a commitment with the Portuguese Army. I wonder what implications this will this have the development of my course action? Do the same rules apply to federal contractor and subcontractor work performed overseas?

It was six months after returning from Kosovo and I joined Jorge, in the country of East Timor. Jorge had the opportunity to take a position as a military observer in a United Nations (UN) mission, UNMIT. This is the second UN mission in this country. Jorge participated in the first mission, knew about the history of the country and convinced me this could be a once in a life time adventure. I agreed and I was eager for the adventure. I brought to a conclusion my career in the Army National Guard and with it my federal job. At the same time I saw this as an opportunity to further advance my formal education and enrolled in a distance learning program.

I soon found myself taking a trip back ward in time. I had to recall all of the tips and tricks of the 48kbs dial-up days. The good aspect of a modem is that it does not rely on electricity. Many days I sat sweating and hoping my battery operated fan and laptop would hold out a few more hours. I also came to realize generalizations made in my text books did not apply in an undeveloped country. It seems those in developed countries have forgotten that not every country has the bandwidth required to stream video or even files over 3 megabytes. Even the commercials on the BBC boast about how the Internet has changed the world. Doesn’t East Timor count as part of the world?

Despite the lack of electricity, technology infrastructure and sense of security both Jorge and I found plenty of other differences to enjoy. In fact returning to a developing country is not an option out of the question. Is it possible to work as a federal contractor or subcontractor in a developing country? The country does have the presence of two US government organizations. One is a US embassy and the other is US Aid. As these are government organizations do they follow the same procurement rules as those located in the US?

Just as Jorge’s tour in East Timor was ending he was offered a two year secondment position in New York working for the United Nations. I am finally positioned with enough availability to resources that should allow me to find an answer to my initial question “What do I have to do to become a federal contractor or subcontractor?”

Method of Study

My research strategy is two fold and hence, a combination of two methods, a case study and multi criteria decision analysis. Further, my research topic will concentrate heavily on marketing, an aspect usually found in a business plan, precisely selling to the federal government. The marketing portion of a business plan is considered the core as it identifies the market and size of the market (Skloff, 2008).

Secondly, the use a formal method specific to decision making. The US Army employs such process in the preparation of any decision brief or staff study. In the past I have also used the US Army’s MCDA process. I find two aspects of the development process particularly interesting. First, is the strict adherence to developing the artifacts necessary to document the situation, criteria and alternatives. Secondly, the use of mathematical tools, to quantify feelings, values or morals that inheritably influence our decisions represents to me a simplistic and harmonic relationship that can exist between science and humanity. I believe a decision representative of both science and humanity represents one of the purest decisions possible. It is interesting to note that the complimentary aspect of science and humanities is the embodiment of the New Humanities Initiative in development at Binghamton University in New York (Angier, 2008). Additionally, the final artifacts derived from the MCDA serve as a repository to assist in answer the question, “Why did I make that decision?” if the question should arise.

Extensive Narrative Description To Further Define Case And Contents

I tend to solve problems by looking at attributes that might make up some form of an alternatives back toward the problem. This is also known as a bottoms up approach (xxxxxxxxx). I tend to separate the possible attributes into three categories, possibilities I cannot apply to my situation, possibilities that I can certainly apply to my situation and possibilities that with the right manipulation or interpretation might apply to my situation. My view toward this problem is no different.

Being a federal contractor or subcontractor entails starting a business and all of the responsibilities that go along with that. There are many books written on the topic of starting a new business and plenty of advice freely available on the Internet. This study is not about the obvious nor is it my objective to regurgitate known regulatory requirements. What would be the point of stepping through the obvious only to find you have no clients or market for your business? Maybe, the market is not even open for competition?

I will be providing custom computer programming services. All supplies and services are categorized and further classified using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). The corresponding code associated with custom computer programming services is 541511 (US Census Bureau The Economic Classifications Development Branch, 2007). The first two digits provide a broad category and in the case of

Development Of Issues

Main contractors opt to sublet their work for various compelling reasons not least financial benefits, workload pressures, human or plant resource constraints, and better efficiency [10], [13] and [45]. While majority of the work in a project is carried out by a group of non-repeated subcontractors, meeting the client requirements and achieving project success depend heavily on their performance [3] and [12]. Unfortunately, many contracting firms have underestimated the risk of employing incapable subcontractors. Subcontractors are particularly vulnerable to market fluctuations and extreme economic conditions resulting in a prevalence of high bankruptcy rate, poor business practices and/or non-performance [37], [39], [40] and [46].

Descriptive Detail, Documents, Quotations, Triangulating Data

Identification of critical success factors (CSFs) from the business function perspective as well as their relationships with the project level functions should help enhance organizational performance and project success [7], [8] and [38]. With little attention being attributed to this important issue, this research seeks to identify and classify subcontractor CSFs from the perspective of the principal stakeholders in the construction industry of Hong Kong. For this purpose, subcontractors are broadly classified into two types viz. (i) equipment-intensive subcontractors (i.e. those who are predominantly hired as a result of their specialized plant and equipments) and (ii) labor-intensive subcontractors (i.e. those who are mainly hired on the basis of their specialized labor resources).

In this paper, the key findings from a recent survey on the CSFs for equipment-intensive subcontractors are presented. The paper begins by examining the concept of CSF and its application in the subcontractor domain. The findings of descriptive statistics are then reported. Finally, a factor analysis is employed to classify the CSFs into different factor groups. The results shall provide main contractors a solid basis for the selection and/or evaluation of equipment-intensive subcontractors, while facilitating subcontractors to achieve their organizational success.

Assertions

The SBA manages several socio-economic programs designed to assist the small business owner. They are outlined on their web page. They look straight forward but oh no there are some catches. First, you would think that the SBA goaling categories would match with the socio-economic programs. Well, they don’t. This is a crock. For instance the category of veteran isn’t even a statutory requirement. It’s some sort of ‘token’ category. Sure it shows up on the goaling category but if it is not a statutory requirement then what is it if not a ‘token’ category. Additionally, if a business fits more than on goaling category a single contract for that company might count in more than one category. Therefore, it is only to the benefit of those monitoring agency goaling plans to attempt to award contracts to companies they know will fulfill more than one category.

Many of the SBA goaling categories that I intended to use as alternatives in my course of action development fit the definition of phantom alternatives in this case (Belton & Stewart, 2002, p. 55). There are numerous published that initially have one believe women owned but reading later on it reveals 8(a). The category of veteran isn’t even a statutory requirement. Its some sort of ‘token’ category.

Could it be that I have asked myself the wrong initial question? Maybe, I have trapped myself into a decision pitfall by focusing not on my objectives but instead explored one possible solution to a larger problem (Hammond, Keeney, & Raiffa, 1999, p. 32). While I do not doubt the exploration was worthwhile I also wonder if it is now time to “pause and reexamine the problem definition” (Hammond et al., 1999, p. 23). Maybe, the question should not be “What course of action can I develop to become a federal contractor or subcontractor?” Maybe, the question should be even broader. Possibly, my further investigative question might be more directed toward, “What categories of work would allow me to work as an individual and not be tied down to one company or corporation?”

Construction project management is a difficult task, when one takes into account the complexity, uncertainties and large number of activities involved. The increasing complexity and uncertainty of construction projects have led to many significant losses for the construction industry. Problems related to the management of projects are addressed in many studies. Sambasivan and Wen Soon [1] present several causes for losses in construction project management, such as a contractor’s faulty planning, inadequate contractor experience, problems with subcontractors, shortage of material, non-availability of and failures in equipment, lack of communication between parties and mistakes during the construction stage. Hameri [2] visualises other problems: lack of discipline in controlling design change, diverse views on what the objectives of the project are and poor reactivity to sudden changes in the project environment.

Some considerations on construction project management at the building site need to be emphasized such as the high degree of current uncertainty about the construction process, the predominance of excessively informal decision aid coming from the project manager and the exaggerated over-emphasis given by project managers to controlling time and costs [3]. According to Cooke-Davies [4] there have been several past studies on the success of projects and which factors lead to project success. Despite this, a project may still under-perform and an understanding of project success factors alone is not sufficient for the success of a project [5].

The role of the project manager and his/her leadership style have been addressed as important aspects for the success of a project [5], although most of the literature ignores this [6]. The project manager’s monitoring of tasks and his/her relationship with subordinates seems to be direct related to the performance of the project.

Greek and Pullin [7] also assert that many construction project management teams do not focus on those critical issues of projects. Project management, according to these authors, is an activity characterised by failure and these failures happen for two basic reasons: technical uncertainty and misjudgement of a project’s urgency.

In the context of construction projects, the basic question to be considered is how the project manager can control and monitor the large number of tasks contained in the project schedule, since long term planning hardly ever occurs without any changes. In practice, project managers apply different managerial practices to each type of project task, as they cannot give the same attention to all tasks. Hua Chen and Tau Lee [8] assert that a project manager’s performance is directly related to his/her managerial practices. In their study, a performance evaluation model for project managers was constructed considering leadership behaviours that lead to managerial practices which contain some essential factors that may affect them.

Thus, this paper presents a more structured model for supporting the project manager so as to focus his/her attention on the main tasks of the project network. The identification of these main tasks is attended to by using multiple criteria decision aid methods (MCDA), in order to evaluate simultaneously the several aspects related to the performance of projects such as: deadlines, costs, contractors’ experience and so forth. A case study on the construction of an electricity sub-station was carried out to demonstrate the structured model proposed.

Characterization Of Problem

Projects need to be divided into parts that admit to being manageable. This means defining a set of activities or tasks that are very often inter-related. In construction projects, any given set of activities is usually very large and complex.

In general, different forms of management are applied subjectively to each set of activities (or tasks), without prior assessment of the activities or a study being made of the problem, such decisions being based only on the manager’s experience. An analysis of this decision problem can help tackle each of these activities by using appropriate management methods, as a function of the specific instances of the activities and thus permitting better use of the manager’s knowledge, acquired from his or her experience on previous projects.

Different classes of managerial practices should be defined and used when executing and controlling project activities. These practices are different because the possible associated consequences do require so, for instance:

– A group of activities may require a tighter form of managerial practice, for example, tasks involving subcontractors where the probability of delay is high. This could represent the possibility of a very undesirable consequence for the project. In such cases, the manager would perform the activities himself.

– On the other hand, another group of activities could require a standard form of managerial practice. They might be delegated to a subordinate, in order to keep the project operational as scheduled.

– The project manager could also delegate another group of activities to a subordinate, but in this instance with very close monitoring by him/her. This close monitoring could be necessary with regard to the possibility of a medium undesirable consequence.

Classifying tasks into types of managerial practice are dependent on the context of the problem and should be driven by the project’s objectives. Therefore, several criteria are considered for this purpose.

Research Approach

Despite structured interview, focus group and the Delphi technique can be used to determine the CSFs, a questionnaire survey was considered more appropriate for this research as it can reach a broader group of respondents. Through an extensive literature review (e.g. [1], [9], [24], [28], [32], [34] and [40]) and the discussions with three domain experts who included a senior engineer of a consultancy practice; a project manager of a main contractor; and the owner of a sub-contractor, a preliminary questionnaire consisting of 29 success factors pertinent to ‘equipment-intensive’ subcontractors was designed. The questionnaire was then piloted by the managerial staff of five main contractors and subcontractors specializing in steel-fixing, formwork/falsework, drainage and road pavement, and curtain walling systems. Based on their suggestions, the questionnaire was improved with two other success factors being incorporated in the finalized version. The first section of the questionnaire focuses on general information of the respondents, and the second section consists of 31 success factors relevant to the external and internal issues (Table 1). A 5-point scale with 5 being ‘extremely important’ and 1 being ‘not important’ was adopted to solicit the perceptions on the degree of importance for the set of identified CSFs in relation to the success of equipment-intensive subcontractors.

Table 1. Success factors for equipment-intensive subcontractors

External factors are those impacting on a business which is beyond the control of a company’s management. In general, they are independent of subcontractor’s performance, but could directly affect the success of a subcontractor or even their survival. Since some of these external factors could be triggered by the society, their influence may vary from time to time depending upon the change in public interests, market fluctuations, policy changes, etc. In contrast, the internal factors are those within the control of an organization’s management. Such factors reflect the organization’s present status and performance capability on a project.

Two hundred questionnaires were distributed to various professionals in the Hong Kong construction industries who have ample experience in subcontracting. The target groups include the clients (8%), consultants (11%), main contractors (15%), and subcontractors (66%). The inclusion of the clients and consultants in the sample was because their requirements are usually regarded as the prevalent conditions governing and ‘benchmarking’ the performance of subcontractors at all tiers, while main contractors were sampled as they are the one who select and hire the subcontractors. However, as subcontractors are the main target of this research, the sample size of this group is indeed higher than the other groups.

The survey was launched in different modes such as through email, by hand and also direct meetings. A total of 73 valid questionnaires representing a response rate of 36.5% were received which include 11 clients, 21 main contractors, 26 consultants and 15 subcontractors. Among them, 75% of the respondents were project managers, 3% were top management (e.g. company owners/directors), 11% were chartered professionals, and the rest were frontline workers. All the respondents have considerable experience, e.g. 23% respondents have more than 20 years of experience in the construction industry.

The methods of data analyses mainly consist of the: (i) arithmetic means and rank orders for the identified success factors; (ii) ANOVA tests to confirm whether or not perceptions between different respondents’ group on the success factors were the same; and (iii) factor analysis to unveil the underlying relationships (if any) among the CSFs.

Ranking And Means Of Success Factors

The first part of the analysis aims at identifying the most important success factors for equipment-intensive subcontractors. The arithmetic means and rank orders of the identified success factors were, therefore, derived from the total sample to determine the level of importance. Since all the success factors should have a mean which is different from zero, a one sample t-test was conducted at a 5% level of significance with a test value of zero in order to evaluate the significant level of each of the 31 identified success factors statistically.

Table 2 summarizes the mean ratings along with their respective rankings of the 31 success factors according to the total sample. Should two or more factors be having the same mean scores, the one with the lower standard deviation is deemed more important. The significance levels derived from the one sample t-test are also included in Table 2. The results confirm that the significance levels of all the success factors in the one sample t-test are less than 0.05 indicating that they are all statistically significant. Factors with means exceeding or equal to 4 are recognized as the CSFs. Seventeen success factors in the total sample receive a mean score of 4 or above, with “timely completion”, “relationship with main contractor/client/consultant”, “profit” “cash flow” and “adoption of new technologies/methodologies” being the top five CSFs for equipment-extensive subcontractors despite they are all internal success factors (Table 2). Only three external factors are regarded as CSFs, and they are “machine/plant/equipment price” (ranked 7th), “political situation” (ranked 13th), and “market condition” (ranked 16th). The identified CSFs indicate that although some factors which are beyond the control of a company’s management they contribute to the success of equipment-intensive subcontractors. This type of subcontractors primarily depends on their management skills, experienced manpower and financial strength, and the findings are consistent with those of Shaikh [40] which summarized the major reasons for subcontractor failure.

Table 2. Comparison of means of success factors for equipment-intensive subcontractor

Notes: Sig.1 = significance obtained from one sample t-test; sig.2 = significance obtained from one way ANOVA test; * = significance < adjusted α level (0.05/3 = 0.0167).Notes: Sig.1 = significance obtained from one sample t-test; sig.2 = significance obtained from one way ANOVA test; * = significance < adjusted α level (0.05/3 = 0.0167).

As this research focuses on the equipment-intensive subcontractors, as expected, two specific factors viz. “machine/plant/equipment performance” and “machine/plant/equipment price” with a ranking of 7th and 15th respectively were classified as CSFs. More discussions on these CSFs are given in the factor analysis section.

One-way ANOVA test

Since the respondents were composed of four groups namely the “clients”, “consultants”, “main contractors” and “subcontractors”, a one-way ANOVA test at a 5% level of significance was conducted to explore the existence of any divergence in opinion between the different respondents’ groups. The significance levels derived from the one-way ANOVA test for this study are also indicated in Table 2. Except the factor “program/planning”, most of the factors have the significance levels obtained from the one-way ANOVA test being higher than the adjusted α level of 0.167 (i.e. 0.05/3 = 0.167). This indicates that there is a consistent opinion among the groups for the importance of most success factors examined. As for the factor of “program/planning”, since it has a significance level of 0.015 (i.e. <0.0167) the opinion of the four groups are not in-line with each other. Hence, the a priori and post hoc comparisons were carried to examine which groups were different.

Table 3 shows the results of the a priori test, and the significance level obtained from the test of homogeneity of variances is 0.581 which is higher than 0.05 representing an equal variation within each of the groups. Therefore, the LSD post hoc test, i.e. an equal-variance t-test, was chosen to evaluate the difference among the groups. In Table 3, two statistically significant between-group difference occurrences including the “consultant vs. main contractor” groups and “main contractor vs. subcontractor” groups respectively are found, and both of them have a significance level of less than 0.05. When re-examining the group means in Table 2, it shows that the main contractor has a higher mean than the other two groups indicating that “program/planning” is more important factor to the main contractor than the other groups. An accurate program submitted by each subcontractor is obviously important to the main contractor as their role in a project is to manage and coordinate the schedule of a large number of subcontractors [18].

Table 3.Test results from a priori and post hoc comparisons on factor program/planning

Proposed Model Structure For Assigning Priorities To Activities In Project Management

The structured model proposed aims to assign project tasks into three classes of managerial practice, based on their characteristics in relation to a set of criteria. The application of the model requires two procedures with the aim of obtaining a general view of the problem and to regularly reassess the model.

The initial procedure consist of five steps presented below, and analyses all project activities without considering their inter-relationship only as an important basis for thinking through the problem.

- Building activity networks

- Managerial classes: definition

- Set of criteria: definition

- Assessment of activities for each criterion

- Applying a multiple criteria method in order to classify activities.

The activity networks are used as a way of producing information for the proposed model. The use of the program evaluation review technique (PERT) allows the network to be determined making use of probabilistic judgments about the duration of the project. Methods like PERT and CPM are widely advocated techniques [9], [10] and [11]. However, others network models, such as critical path method (CPM) could be applied.

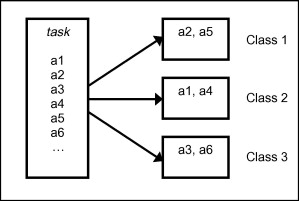

Using project information at hand, the manager should define the classes of managerial practices. This definition is context dependent. For instance, three classes of managerial practices can be considered such as those presented in the previous section. Fig. 1 shows this classification problem.

/var/www/blog-sandbox.itp/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/193153_3.jpg 299×201 24bit N JFIF [OK] 10946 –> 10945 bytes (0.01%), optimized.

The structure of the problem also involves the requirements for defining each class of managerial practice. It is related to the set of criteria to be considered in the evaluation process and configures one of the most important parts of the analysis. This set of criteria will be related, in some way, to the project manager’s view about the objectives of the project. For instance, one can consider criteria such as: task cost, resource mobilization (supply contractor), duration (length), slack, security, variability (measured by the deviation and used when a probabilistic time estimate is used), number of successor activities based on the inter-relation dependence.

Various methodologies can be used to support compiling the set of criteria of the decision problem. Examples are: post-it sessions, constructing cause and effect diagrams, use of cognitive maps, constructing value trees, and so forth (details about these techniques can be found in Belton and Stewart [12]).

The multiple criteria decision aid method is then applied to assign each activity (or task) into a specific class of managerial practices. A central aspect of this proposed structured model is the process of choosing the MCDA method to be used. This choice should involve analysing the context of the problem, the actors and their preference relation structure. The context of this problem is a classification of tasks, as presented in Fig. 1. The decision-maker’s preference (his/her rationality and sensitivity to the imprecision of data) is an important aspect that should be taken into consideration when choosing a method.

The application of this initial procedure will provide a better understanding of the problem and some insights from the model. The model must be reassessed so as to consider the dynamic and changing environment.

Reassessments of the model

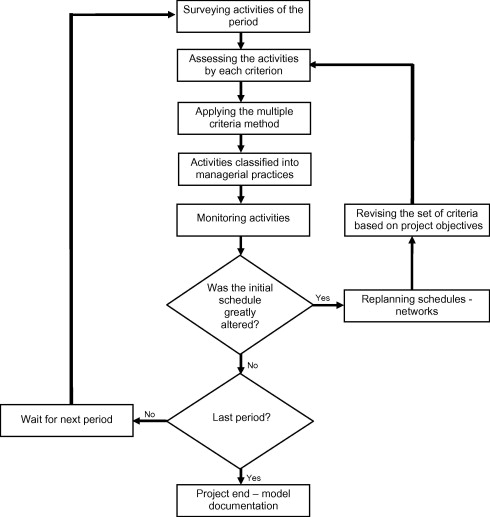

The proposed model must be applied at regular intervals (weekly, monthly, other) and the only activities analysed are those of that specific period. In other words, the model must be used periodically, in accordance with the length of the project.

It is understood that the model must be re-assessed periodically because changes may take place when carrying out project activities. Due to the uncertainties of the planning process, it may be necessary to reprogram all or part of the set of project activities, that is, to re-plan. In this case, it may well be necessary to re-think the objectives and to put forward a new schedule of activities. This is an interactive feature of planning and controlling projects. The structure proposed can be visualized in Fig. 2.

For each period of evaluation, a new set of tasks (or activities) is assembled and the data should be updated. The evaluation of the activity over a specific period (pi, i = 1 to p) is used to account for the changes which occurred in the previous period (pi−1). As an example, these changes can occur if some activity is delayed or new information and/or constraints are added in the process of carrying it out. In addition, some adjustments to the multiple criteria decision making method may be necessary, such as changes to parameters. When significant changes occur it may be necessary to re-plan.

The application of the proposed structure should be continuous until the conduct of the project ends. In other words, a new period is started after monitoring the conduct of the previous period and the process is repeated until all periods are finished.

As a result, the manager will make better use of his or her time through sound managerial practice for each type of task and thus be able to focus on the most relevant activities which need greatest attention.

Factor Analysis

The main purpose of the factor analysis is to reduce the number of variables with a minimum loss of information and to detect the structure in the relationships between variables [11]. A principal component method of extraction was applied for the factor analysis, while the varimax with Kaiser normalization of rotation was used. The principal components analysis aims to mathematically derive a relatively small number of variables to convey as much of the information in the seventeen CSFs as possible. Variables related as a group, or that are answered most similarly by the participants will be identified.

Table 4 shows the results of the factor analysis. A factor loading with an absolute value of less than 0.4 is suppressed. Factor loadings with an absolute value of greater than or equal to 0.4 have generally been suggested [42], which therefore shares at least 15% of variance with the factors and are considered to be able to reflect an important association between the measured CSFs and a component. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity, a statistical test to examine the presence of correlations among the variable, is 347.191 and the associated significance level is 0.000 suggesting that the population correlation matrix is not an identity matrix. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy is 0.522 which is higher than 0.5 and is considered acceptable. Six components with eigenvalue of greater than 1 were extracted. Together they accounted for over 65% of the total explained variations. The meanings of the six components are interpreted as follows:

Table 4.Tabular presentation of a six-component solution from principle component analysis

Notes: Extraction method: principal component analysis.

Rotation method: varimax with Kaiser normalization.

Rotation converged in seven iterations.

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = 0.522.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity χ = 347.191; df = 136; sig. = 0.000.

Factor loadings of an absolute value <0.4 were suppressed.

- Component 1: market position The “market position” component consists of the “market condition”, “reputation”, and “company history”, which is indeed one of the key business problems for small construction companies [34]. Market condition can be related to the analysis of the marketplace in which an organization operates or has interest in developing its position [1]. For the subcontractors, to understand which market position they own shall enhance their chance of success in securing new jobs. To maintain a good market position depends on the ability to correctly analyzing the market condition, building up good reputation, and establishing a sound company history. Good market condition gives adequate job opportunities to even weak subcontractors and can help foster some potential subcontractors. Adversely, a poor market would knock out some subcontractors with relatively poor performance or poor financial status through vigorous competition. While facing severe competition and reduced demand, reputation and company history are the key performance evaluation criteria for subcontractors to win any jobs. Subcontractors who own a good reputation and sound company history are considered more capable of maintaining a high quality performance or improving inadequate performance [29], [33] and [43], and hence they will gain a greater chance of success.

- Component 2: Equipment-Related Factors. The “machine/plant/equipment price”, “machine/plant/equipment performance”, “payment method”, and “program/planning” constitute the second component. Most of the subcontractors compete based on their price and performance [21], [33] and [45]. For equipment-intensive subcontractors, the “machine/plant/equipment price” and “machine/plant/equipment performance” are directly related to the overall cost and performance. As to the other two factors, delay in payment by main contractors has become more and more frequent in this industry and subcontractors without having a good payment monitoring mechanism could easily lose control over cash flow and fall into trap of high interest loans which may subsequently lead to company collapse [39] and [40]. Meanwhile, to manage time and resources effectively, accurate “program/planning” is a must to ensure the smooth implementation of works [14] and [25]. A good “program/planning” requires the critical path be precisely derived, resources be appropriate allocated, and an elastic contingency be allowed to cover any unforeseeable incidents. Usually experienced project coordinators and planners are required to propose, monitor and adjust the program to achieve success. Moreover, since payments may be linked with certain milestones, the plan to achieve milestones would also be important to cash flow and financial control.

- Component 3: Human Resources. The human resources component comprises “staff team spirit/morale” and “staff performance”. Rockart [35] identified company morale as one of the CSFs for organizations. Munro and Wheeler [28] stated that the CSF for the success of each business unit was “human resources” as identified by all managers in their field study. A company consists of a team of different expertise who are playing different roles. It needs cooperation within the team to achieve the objectives. Cooperation cannot be established if staffs are working individually or without any team spirit. Morale will also affect the performance and cooperation among staff. Staff with a high level of morale can complete the works at or even above the normal standard, and such ideal working condition is good to both the staff and company in the long-term pursuance of business goals. As staff performance directly affects the quality and timely performance of a project, the availability of sufficient qualified staff is critical to the success of any organizations [28].

- Component 4: Earnings. Earnings are widely recognized as important success determinants for any organizations and projects. “Profit” and “growth in revenue” are the two major indicators of earnings. Profit basically is the difference between the incomes and expenditures, and could therefore reflect both the abilities of money-making and cost saving. As the fundamental goal of a company is to make money, this factor was always one of the major cores when assessing success of any businesses. Growth in revenue actually represents an increase in scale, improvement in financial management, and good business or market strategy. While subcontractors are among the highest in bankruptcy rate within the construction industry [39], earnings indubitably become a CSF for subcontracting organizations.

- Component 5: Managerial Ability To Adapt To Changes. Olsson [31] reiterated the importance of subcontractor coordination aspects. The managerial ability to adapt to the change component consists of “political situation”, “adoption of new technologies/methodologies”, and “management level leadership”. Political situation influences project decisions, community development and fiscal policy [1]. A stable political situation guarantees a predictable investment by the government in the construction field that can help subcontractors control their budget and cash flow. On the other hand, an unstable political situation could lead to unpredictable changes of business environment and this may make the subcontractors commercially and financially out of control or even collapse. The ability of the management to recognize the political environment is a key factor for the construction industry and project success [1], [4] and [8]. Equipment-intensive subcontractors rely immensely on the technology or methodology used. Experience from industrial revolution reveals that an exploration in advance technology would bring back much reward, especially in the developed countries. Any new technology can improve quality and efficiency and shall reduce wastage, cost and not to mention about the time. Companies which are eager to adopt new technologies/methodologies can always run in the forefront of their competitors in the industry and have more rooms to further develop their business [34]. Companies always spend much money to hire outstanding management expertise to look after their business. Schaufelberger [39] believes that a lack of managerial maturity contributes to subcontractor business failure. Furthermore, in an increasingly competitive environment, the managerial skills of potential subcontractors often become one of the key criteria measured by the main contractor [2].

- COMPONENT 6: PROJECT SUCCESS RELATED FACTORS. The project performance component includes “cash flow”, “relationship with main contractor/client/consultant”, and “timely completion”. One of the major determinants for subcontractor’s success is how successful the projects being handled. For subcontractors, while completing the tasks for the main contractor but failing to bill the main contractors promptly may result in unexpected cash flow shortfall [39] and [40]. For equipment-intensive subcontractors, the cost of owning and operating equipment is a significant part of their business. Investing too much financial resources in equipments may degrade the firm’s ability to finance its cash flow requirements [39]. Maintaining a healthy cash flow can undoubtedly allow the subcontractors to be more flexible in running their business especially at times of uncertainty. A positive cash flow record can reflect high creditability to bankers so that higher limit of loan and longer repayment period can be provided. It would also help any future bidding due to its stability in providing continuous services.

Under the current practice subcontractors are selected by the main contractors or directly nominated by the clients, and consultants can also give suggestions to the clients especially when involving some special design tasks that necessitate special technologies or skills. Good relationship is a predominant factor when selecting subcontractors [40]. Kumaraswamy and Matthews [21] pointed out the importance of relationships between the main contractor and subcontractor; the subcontractor and sub-subcontractor; as well as subcontractor and consultants if we were to ensure project success and reduce cost. For any project, success can primarily be broken down into budget success, schedule success, and quality success [9] and [25]. Timely completion is no doubt a CSF for subcontractors.

Multiple Criteria Decision Aid Methods

The MCDA area has a large set of tools the purpose of which is to help the decision-maker solve a decision problem by taking into account several, often contradictory, points of view. In general, multi-criteria decision-aid methods are divided into three large families [13]: unique synthesis criterion, consisting of aggregating different points of view into a unique function which must subsequently be optimised; the outranking synthesis approach, using methods which aim first to build a relation, called an outranking relation, which represents the decision-maker’s strongly established preferences, given the information at hand; and the interactive local judgment approach, proposing methods which alternate calculation steps and dialogue steps.

The outranking synthesis approach has been applied to build the proposed model. The elimination and choice translating algorithm (ELECTRE) method is widely examined in the literature [12], [13] and [14]. The choice of the method is an important issue discussed in the topic choosing the multicriteria method.

Multiple criteria decision aid methods (MCDA) have been applied to a variety of problems, such as maintenance outsourcing [15], maintenance strategy [16], water supply management [17], project risk assessment [18], multi-criteria risk analysis [19], service outsourcing contracts [20] and construction bidding [21]. Mian and Dai [22] show the main decision problems related to project management to be resource allocation, prioritising the project portfolio, selection of managers, budget evaluation and selection of salespersons.

Closing Vignette

Throughout the process of conducting the project, the activities classified in class 3 merit greatest attention from the project manager, as these are the ones that meet the norms specified for that category, and can cause negative impacts in terms of the project’s objectives.

This study also allows the manager to be more effective in managing projects in a dynamic environment, as he/she can use the managerial practice appropriate to each type of task and thus focus efforts on aspects that really matter. In this case study, the project manager will not be involved in performing tasks related to purchase reports. The use of the model is also very important when the project manager is involved in a multiple project environment. So, having applied the proposed decision structure and considering all the periodic re-assessments of the model, the project manager has the option to anticipate the problems that may occur and draw up contingency plans at the time when the preceding tasks are still being carried out.

The model developed requires the involvement of the whole project team in order to keep information up-to-date and to carry out the constant reassessments of the model. Therefore, the use of a decision support systems DSS and an integration system to facilitate communication between teams is very helpful for applying these techniques.

Finally, the greatest benefit to be derived from applying the multiple criteria decision structure to construction projects is in order to analyse the problem better and to provide a well-structured model that can consider several criteria simultaneously. This model prompts project managers into thinking about the trade-offs among project objectives.

Contribution of multicriteria method on project management practices has been shown to be a very useful. Several other models in this contexts may be developed in order to insure a formal approach for the project management practice. Future work may be conducted regarding exploring other different methods and their particular requirements associated with the projects demands. Also, different kind of problems may be analysed, such as: decision problems related to risk management could be conducted taking into account multiple objectives.

The FAR specifies the acquisition rules government agencies are to follow. In short it governs the rules associated with different contracting vehicles, dollar cut offs, how to use small and large businesses in regards to procurement.

After two years she finally established advertising of her services on the GSA schedule. The amount of paperwork and time was enormous. In addition one has to be in business for three years before applying. Altogether, it could take five years to get on the GSA schedule.

Subcontractors undertake considerable proportion of works awarded to the main contractors, and hence the overall project success relies heavily dependent upon the successfulness of the subcontracting organizations which more volatile to market fluctuations and changes. Since most of the performance indicators and related initiatives of clients and/or main contractors mainly target on achieving the ultimate project results, the underlying CSFs of subcontracting organizations are often ignored by those principal stakeholders. Realizing the significance, this paper has reported the findings of a related research initiative, which mainly covered the CSFs of a subgroup of contractors known as equipment-intensive subcontractors who are predominantly considered for their rich plant and equipment resources in addition to their other capacities.

In this research, 31 success factors were initially identified and rank ordered, and the top five CSFs identified are “timely completion”, “relationship with main contractor/client/consultant”, “profit”, “cash flow”, and “adoption of new technologies/methodologies”. The identified CSFs can be used to assist equipment-intensive subcontractors to formulate organizational strategies to improve their chance of success and avoid business failure. The CSFs for equipment-intensive subcontractors can help main contractors to benchmark the performance of subcontractors under this specialized category and to determine whether an equipment-intensive subcontractor is capable of successfully completing a project before any company is commissioned to do the work.

Through the factor analysis, the 17 CSFs are grouped into six components namely: (i) market position, (ii) equipment-related factors, (iii) human resources, (iv) earnings, (v) managerial ability to adapt to changes and (vi) project success related factors. The findings should enable managers of construction companies to determine the essential determinants of success to an equipment-intensive subcontractor so that effort can be channeled to those critical components when managing the equipment-intensive subcontractors. By focusing on the above six broad areas and linking the identified CSFs to performance measurements as well as setting performance standards for the construction industry, the performance of equipment-intensive subcontractors can eventually be improved.

References

- Angier, N. (2008). Curriculum Designed to Unite Art and Science. The New York Times. Web.

- Belton, V., & Stewart, T. J. (2002). Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis (p. 372).

- Emery, G. (2004). Let’s get serious. Washington Technology, 19(12).

- Hammond, J. S., Keeney, R. L., & Raiffa, H. (1999). Smart Choices (p. 244).

- How 25 Small Federal Contractors Beat the Odds – IT Channel – IT Channel News by CRN and VARBusiness. (n.d.).

- Skloff, A. (2008). Starting a New Business: Realizing Your Dream [Lecture]. Summit, NJ.

- US Census Bureau The Economic Classifications Development Branch. (2007). NAICS – North American Industry Classification System Main Page. North American Industry Classification System.

- USWCC-Report-to-Congress.pdf (application/pdf Object). (n.d.). Web.

- Billions in Set-Asides. (n.d.).. Web.

- Ensuring Small Business Access to Federal Marketplace: hearing before the Subcommittee on Contracting and Technology of the Committee on Small Business of the House of Representatives. (2008).. Longworth HOB.

- Seven of 24 federal agencies meet small business contracting goals, says SBA. (2007). Hudson Valley Business Journal, 18(35), 25-26. doi: Article.

- USWCC-Report-to-Congress.pdf (application/pdf Object). (n.d.). Web.

- Ruling on minority contracts worries contracting officials – Federal news, government operations, agency management, pay & benefits – FederalTimes.com. (n.d.).

- Weigelt, M. (2008). Court ruling could affect future small-business set-asides. Federal Computer Week.

Bibliography

- M. Sambasivan and Y. Wen Soon, Causes and effects of delays in Malaysian construction industry, Int J Project Manage 25 (5) (2006), pp. 517–526.

- Ari-Pekka Hameri, Project management in a long-term and global one-of-a-kind project, Int J Project Manage 15 (3) (1997), pp. 151–157.

- A. Laufer and G. Howell, Construction planning: revising the paradigm, Project Manage J 24 (3) (1993), pp. 23–33.

- T. Cooke-Davies, The “real” success factors on projects, Int J Project Manage 20 (3) (2002), pp. 185–190.

- L.S. Pheng and Q.T. Chuan, Environmental factors and work performance of project managers in the construction industry, Int J Project Manage 24 (2006), pp. 24–37.

- J.R. Turner and R. Muller, The project manager’s leadership style as a success factor on projects: a literature review, Project Manage J 36 (1) (2005), pp. 49–61.

- D. Greek and J. Pullin, Overrun, overspent, overlooked, Prof Eng 12 (3) (1999), pp. 27–28 Bury St. Edmunds.

- S. Hua Chen and H. Tau Lee, Performance evaluation model for project managers using managerial practices, Int J Project Manage 25 (6) (2007), pp. 543–551.

- PMI. A guide to the project management body of knowledge – PMBOK GUIDE: Project Management Institute; 2004.

- Maylor H. Project Management: paperback; 2002.

- J. Turner, The handbook of project based management: improving processes for achieving your strategic objectives, McGraw-Hill, New York (1999).

- V. Belton and J. Stewart, Multiple criteria decision analysis – an integrated approach, Kluwer Academic Publishers, London (2002).

- P. Vincke, Multicriteria decision-aid, Wiley& Sons, Bruxelles (1992).

- B. Roy, Multicriteria methodology for decision aiding, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands (1996).

- A.T. Almeida, Multicriteria modelling of repair contract based on utility and ELECTRE I method with dependability and service quality criteria, Ann Oper Res 138 (2005), pp. 113–126.

- A.T. Almeida and G.A. Bohoris, Decision theory in the maintenance strategy of a standby system with gamma distribution repair time, IEEE T Reliab 45 (2) (1996), pp. 216–219.

- D.C. Morais and A.T. Almeida, Group decision-making for leakage management strategy of water distribution network, Resour Conserv Recy 52 (2) (2007), pp. 441–459.

- J. Zeng, An Min and N.J. Smith, Application of a fuzzy based decision making methodology to construction project risk assessment, Int J Project Manage 25 (6) (2007), pp. 589–600.

- A.J. Brito and A.T. Almeida, Multi-attribute risk assessment for risk ranking of natural gas pipelines, Reliab Eng Syst Safe (2008) 10.1016/j.ress.2008.02.014.

- A.T. Almeida, Multicriteria decision model for outsourcing contracts selection based on utility function and ELECTRE method, Comput Oper Res 34 (12) (2007), pp. 3569–3574.

- J. Seydel and D.I. Olson, Multicriteria support for construction bidding, Math Comput Model 34 (5) (2001), pp. 677–701.

- S.A. Mian and C.X. DAÍ, Decision-making over the project life cycle: an analytical hierarchy approach, Project Manage (1999), pp. 40–52.

- Yu W. Aide multicritere a la decision dans le cadre de la problematique du tri: methodes et applications. PhD thesis, LAMSADE, Universite Paris Dauphine; 1992.

- V. Mousseau and R. Slowinski, Inferring an ELECTRE TRI model from assignment examples, J Global Optim 12 (1998), pp. 157–174.

- L.C. Dias and V. Mousseau, Iris: a DSS for multiple criteria sorting problems, J Multi-Criteria Anal 12 (2003), pp. 285–298.

- G.L. Abraham, Critical success factors for the construction industry. In: K.R. Molenaar and P.S. Chinowsky, Editors, Proceedings: construction research congress, winds of change: integration and innovation in construction, ASCE Press, Honolulu, Hawaii (2003), pp. 521–529.

- V. Albino and A.C. Garavelli, A neural network application in sub-contractor rating in construction firms, Int J Project Manage 16 (1) (1998), pp. 9–14.

- D. Arditi and R. Chotibhongs, Issues in subcontracting practice, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 131 (8) (2005), pp. 866–876.

- D.B. Ashley, C.S. Lurie and E.J. Jaselskis, Determinants of construction project success, Project Manage J 18 (2) (1987), pp. 69–79.

- H.A. Bassioni, A.D.F. Price and T.M. Hassan, Building a conceptual framework for measuring business performance in construction: an empirical evaluation, Constr Manage Econ 23 (5) (2005), pp. 495–507.

- D.J. Bryde and L. Robinson, Client versus contractor perspectives on project success criteria, Int J Project Manage 23 (8) (2005), pp. 622–629.

- C.R. Byers and D. Blume, Tying critical success factors to systems development, Inform Manage 26 (1) (1994), pp. 51–61.

- A.P.C. Chan, D. Scott and A.P.L. Chan, Factors affecting the success of a construction project, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 130 (1) (2004), pp. 153–155.

- D.K.H. Chua, Y.C. Kog and P.K. Loh, Critical success factors for different project objectives, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 125 (3) (1999), pp. 142–150.

- A.M. Elazouni and F.G. Metwally, D-SUB: Decision support system for subcontracting construction works, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 126 (3) (2000), pp. 191–200.

- J.F. Hair, R.E. Anderson, R.L. Tatham and W.C. Black, Multivariate data analysis (3rd ed.), Macmillan, New York (1992).

- J. Hinze and A. Tracey, The contractor–subcontractor relationship: the subcontractor’s view, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 120 (2) (1994), pp. 274–287.

- T.Y. Hsieh, Impact of subcontracting on site productivity: lessons learned in Taiwan, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 124 (2) (1998), pp. 91–100.

- Jaselskis EJ. Achieving construction project success through predictive discrete choice models, Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas; 1988.

- M. Jefferies, R. Gameson and S. Rowlinson, Critical success factors of the boot procurement system: reflection from the Stadium Australia case study, Eng Constr Archit Manage 9 (4) (2002), pp. 352–361.

- S. Kale and D. Arditi, General contractors’ relationships with subcontractors: a strategic asset, Constr Manage Econ 19 (5) (2001), pp. 541–549.

- K. Karim, S. Davis, M. Marosszeky and N. Naik, Designing an effective framework for process performance measurement in safety and quality, Constr Inform Quart 5 (4) (2003), pp. 19–23.

- K. Karim, M. Marosszeky and S. Davis, Managing subcontractor supply chain for quality in construction, Eng Constr Archit Manage 13 (1) (2006), pp. 27–42.

- Khandelwal VK, Ferguson JR. Critical success factors (CSFs) and the growth of IT in selected geographic regions. In: Proceedings of the 32nd Hawaii international conference on system sciences, vol. 7, 1999. p. 7014–26.

- C.H. Ko, M.Y. Cheng and T.K. Wu, Evaluating subcontractors performance using EFNIM, Automat Constr 16 (4) (2007), pp. 525–530.

- M.M. Kumaraswamy and J.D. Matthews, Improved subcontractor selection employing partnering principles, J Manage Eng ASCE 16 (3) (2000), pp. 47–57.

- B. Li, A. Akintoye, P.J. Edwards and C. Hardcastle, Critical success factors for PPP/PFI projects in the UK construction industry, Constr Manage Econ 23 (5) (2005), pp. 459–471.

- R. Martin, Do we practice quality principles in the performance measurement of critical success factors?, Total Qual Manage 8 (6) (1997), pp. 429–444.

- Mbugua LM, Harris P, Holt GD, Olomolaiye P. A framework for determining the critical success factors influencing construction business performance. In: Proceedings: association of researchers in construction management 15th annual conference, vol. 1, Liverpool John Moores University, Liverpool; 1999. p. 255–264.

- C.L. Menches and A.S. Hanna, Quantitative measurement of successful performance from the project manager’s perspective, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 132 (12) (2006), pp. 1284–1293.

- Mendel TG. Subcontractor status reporting. Transactions of the American association of cost engineers annual meeting, Radisson-Denver Hotel, Denver, Colorado, American Association of Cost Engineers; 1985. p. A.5.1–3.

- J. Miller and B.A. Doyle, Measuring the effectiveness of computer-based information systems in the financial systems in the financial services sector, MIS Quart 11 (1) (1987), pp. 107–124.

- C.M. Munro and B.R. Wheeler, Planning, critical success factors, and management’s information requirements, MIS Quart 4 (4) (1980), pp. 27–38.

- S.T. Ng and R.M. Skitmore, Client and consultant perspectives of prequalification criteria, Build Environ 34 (5) (1999), pp. 607–621.

- M.I. Okoroth and W.B. Torrance, A model for subcontractor selection in refurbishment projects, Constr Manage Econ 17 (3) (1999), pp. 315–327.

- R. Olsson, Subcontract coordination in construction, Int J Product Econ 56–57 (1998), pp. 503–509.

- M.K. Parfitt and V.E. Sanvido, Checklist of critical success factors for building projects, J Manage Eng ASCE 9 (3) (1993), pp. 243–249.

- PCICB. Guidelines on subcontracting practice. Provisional Construction Industry Co-ordination Board, HKSAR; 2002b.

- Pullig C, Chawla S. A multinational comparison of critical success factors and perceptions of small business owners over the organizational life cycle, presented at the Academy of International Business, US Southwest Chapter, Dallas, Texas; 1998.

- J.F. Rockart, Chief executives define their own data needs, Harvard Bus Rev 57 (2) (1979), pp. 81–93.

- J.F. Rockart, The changing role of the information systems executive: a critical success factors perspective, Sloan Manage Rev (pre-1986) 24 (1) (1982), pp. 3–13.

- J.S. Russell and M.W. Radtke, Subcontractor failure: case history, AACE T (1991), pp. E.2.1–E.2.6.

- V. Sanvido, F. Grobler, K. Parfitt, M. Guvenis and M. Coyle, Critical success factors for construction projects, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 118 (1) (1992), pp. 94–111.

- J.E. Schaufelberger, Causes of subcontractor business failure and strategies to prevent failure. In: K.R. Molenaar and P.S. Chinowsky, Editors, Proceedings: construction research congress, winds of change: integration and innovation in construction, ASCE Press, Honolulu, Hawaii (2003), pp. 593–599.

- N.M. Shaikh, How to select the proper subcontractor – part 1, Hydrocarb Process 78 (6) (1999), pp. 91–96.

- J. Sommerville and H.W. Robertson, A scorecard approach to benchmarking for total quality construction, Int J Qual Reliab Manag 17 (4/5) (2000), pp. 453–466.

- J. Stevens, Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah, NJ (1996).

- Tang H. Construct for excellence, report of the construction industry review committee. The Printing Department, HKSAR Government, HKSAR; 2001.

- R.L.K. Tiong, CSFs in competitive tendering and negotiation model for BOT projects, J Constr Eng Manage ASCE 122 (3) (1996), pp. 205–211.

- V. Wadhwa and A.R. Ravindran, Vendor selection in outsourcing, Comput Oper Res 34 (12) (2007), pp. 3725–3737.

- Yau HWJ. A study of the subcontracting in the Hong Kong construction industry and its impact on the management of quality. MBA Dissertation, Faculty of Social Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, HKSAR; 1991.