Introduction

Efficient organizations are vigilant in finding ways to improve their efficiency as a group. For example, too frequent meetings are considered a major source of conflict and discontent among employees (Crowe, Cresswell, Robertson, Huby, Avery, & Sheikh, 2011). Hosley (2010) discovered that the productivity of a firm largely depends on the degree of responsiveness within the company structure. The entire leadership structure is responsible for making decisions in the firm. The different decision-making stakeholders want to ensure a higher degree of accuracy on the solutions provided, which is possible through enhancing cohesiveness within the organization (Cahalane et al., 2010).

Recent developments in addressing team ineffectiveness involve the use of technology to meet the growing needs and responsibilities of organizational members. One revolutionary strategy that many organizations have adopted is the Group Support System (GSS).

Group Support System (GSS) is a set of approaches, technology and software whose primary function lies in utilizing techniques that focus on improving communication and decision making (Crowe et al.). In this respect, introducing GSS settings can contribute significantly to value management and develop a new powerful network within which shape ethical and moral codes (Chen & Kyaw-Phyo, 2012). Because little connection has been revealed between GSS approaches and organizational efficiency in terms of value creations, specific emphasis should be placed on examining the related researches supporting this assumption.

The development of computer-based group support can provide new opportunities for organizational development and team building (Hayward, 2012). It is important to deliberate on the strategic issues that will prevail in terms of the needs of the organizational development. Such a perspective allows managers to identify the pertinent information that is important for choosing the appropriate systems for sustainable development of an organization. In addition, such knowledge creates further assistance in improving a GSSs Group Support System to ensure efficient measures (Niederman et al., 2008). Using a consistent organizational network within an organization improves the overall structure of an organization and establishes fixed norms, values, and standards of behavior. By combing the Internet, emerging technologies, and the findings in social behavior as they relate to group work, with the exploding growth currently being experienced in communication, the results and the rate of introduction of new ways of collaborating will be absolutely amazing (Lu, Wang, Xing, Yao, & 2010). Chapter 1 discusses the problem, purpose, and method of this proposed qualitatative, research case study is to explore the consequences of the integration of GSSs on the efficiency of organizational meetings.

Background of the Study

Group Support Systems create benefits for a number of organizations because the introduce significant improvements at different levels of management ( Chandra et al., 2010). In a globalized setting, new decision-making models have been invented to adjust to a virtual environment (Turban et al., 2011). While evaluating the efficiency of group meetings beyond the virtual environment, inattentiveness, lack of focus, and unawareness of the topic of discussion can lead to inadequate decisions. This lack of attention to details is of particular concern to the action planning approaches (Bakker et al., 2011).

Most organizations spend considerable amounts of time on meetings rather than the actual tasks and goals needed to be achieved (Crowe et al., 2011). Inefficient distribution of time and resources lead to decrease in organizational effectiveness. Hence, meetings should be kept short so that workers can concentrate more on action instead of discussion (Bessiere et al., 2009).

The integration of technology supported systems into a collaboration model of an organization can facilitate the prediction of performance and productivity outcomes (Eschenbrenner, et al. (2008). In fact, the collaborative use of technology closely relates to the theory of acceptance and closure theory, which identifies the degree of the interaction between social environment and technology (Brown et al., 2010). In addition, the development of technologically advanced settings can allow organizations to sustain a competitive advantage of over other organizations which are less concerned with innovation and change (Owens et al., 2011). However, despite the fact that introducing powerful computer-based approach to group work is beneficial, little research has been conducted on the role of GSSs in value creation and development of new standards, norms, and ethics contributing to the efficiency of an organization. This is of particular concern to such aspects as leadership, team building, employee engagement, and organizational learning (Huang et al., 2010).

Problem Statement

Traditional conduct of meeting, conferences, and projects has been premised on face-to-face communication and constant interaction between group members. Indeed, the presence of all the participants facilitates the generation of ideas and develops a powerful framework for further discussion (Andres, 2002). Introduction of technology, therefore, widens the opportunities for alternative measures in exchanging ideas in case face-to-face meetings are impossible (Richey et al., 2012). Constant communication and possibility of instant messaging is a step forward to an advanced and efficient development of ideas and decisions.

The problem to be addressed by the study is that most of the meetings held by boards of directors are not efficient in terms of time and task orientation. Within the context of human resource management, the meetings tend to take place more regularly, consuming time and money (Richey et al., 2012). Ineffective teamwork and communication in such cases further waste company time and effort. In this respect, Niederman et al (2008) state that the information technology domain of such organizations, specifically GSS, may not be maximized in creating a useful, predictable or even reputable improvement of meeting the outcomes of the organization. Hence, this study explores the wide possibilities of GSS in terms of optimizing efficiency in organizational meetings as well as the constraints in its implementation. It will also investigate GSS’s advantages and disadvantages at various directorates level of the DHHQ’s in Falls Church, Virginia.

The significance of the study addresses the re-evaluation of approaches to holding a meeting, including devices and media platforms for information transmission, the structure of group projects, and sequence of settled tasks. Normally, GSS develops improved cohesiveness within the organizational group. It also helps to create ideas and agendas that are consistent with normal organizational traditions through the decision-making process. On the other hand, the accessibility of GSS may minimize employees’ engagement and willingness to participate in online meetings because virtual collaboration can lead to decreased awareness of the importance of the event (Bose, 2003). The success of virtual collaboration depends on the employees’ position. It is purposeful to define the major challenges of technology integration, as well as outline how leadership, employees’ engagement, team building, and organization learning can be redeveloped to fit in the requirements of GSS settings.

Briefly, the main research question posed by this study is “What are the consequences of the integration of GSSs on the efficiency of organizational meetings in various directorate levels of the DHHQ, Falls Church, VA.?”

Purpose of the Study

The major purpose of this proposed qualitative case study is to explore the consequences of the integration of GSSs on the efficiency of organizational meetings in various directorate levels of the DHHQ, Falls Church, VA. Specifically, the purposes of the study are enumerated as follows:

- To define the degree of organization’s readiness to implement GGSs to a traditionally structured environment;

- To assess whether the application of GSSs will be a factor on the prevention of negative effects meetings may pose to productivity;

- To understand how GSS application will contribute to better levels of motivation, satisfaction, communication amongst members of the organization

Significance of the Study

As noted by Webne-Behrman (2008), the term group process refers to the procedures implemented by closely working member of an organization, in order to come up with viable solutions to common organizational problems. Kim (2006) stated that group processes enables leaders to develop interventional measures that can be applied to change the less desirable attributes showcased by different members of an organization. Organization theory views an organization as a group of people who work together to accomplish set goals and objectives (Cusella, 2009). From this description, it can be argued that groups play a pivotal role towards the success of any organization (Hoffman & Parker, 2006). Research will set out to further our understanding of this theory and the applicability of GSSs in an organizational setting.

The concept of GSSs is relatively new. GSS are a promising vehicle for better managing groups (Wilson, et al., 2010). The study of GSS as an aid to group decision-making in organizations is important to organizational researchers for practical and scientific reasons (DeSanctis and Gallupe, 1987, Huber et al., 1993, Wilson, et al., 2010). Elfvengreen (2008) asserted that GSSs provide an avenue through which meetings can be held without necessarily wasting valuable time and employees’ productivity. A gap exists between the significance of GSSs and their applicability in resolving productivity issues that stem from ineffective meetings (Kilgour, 2010).

Much of the GSSs research published to date does not report the configuration specifics of GSS: the exact instructions given to the group, the guidelines, constraints, and ground rules by which they worked; and the step-by-step mechanics of how their work proceeded (Briggs, Vreede, and Nunamaker, 2003; Santanen, 2005; Niederman, 2008). Though there are lots of documented literatures regarding teamwork and group dynamics, but there is little information on the effects of GSSs in improving meetings and group efficiency. In this study, GSSs and group dynamics will first be explored. Secondly, the structure of the GSS will be explored where its framework in an organizational context will be discussed. Further, the usefulness and significance of GSS to an organization will be focused where its advantages and limitations will be explored.

This study will mainly focus on the role of leader in facilitating meetings and group activities through the inegration of GSS in an organizational context where this research will enable leaders in organizational settings understand: (i) the objective of Group Support Systems, (ii) how meetings should be designed to support the organizational strategic objectives, (iii) how to increase meetings effectiveness through GSS and, (iv) understand the dynamics of comprehensive Group Support System and how it promotes teamwork, commitment and motivation among employees.

Nature of the Study

This study will adopt qualitative research methods. Specifically, it is a case study on Defense Health Agency (DHA), formerly known as Tricare Management Activity (TMA) with headquarters located in Falls Church, VA. This organization is a federal defense agency serving medical needs to the country and worldwide USA Military personnel who are commissioned and non-commisioned on active duty, reservist and retired professionals. Primary information would come from the leaders and employees of the organization. The study will first seek to explore Group Support Systems as well as group dynamics within an organizational context. In addition, the importance and usefulness of GSS to the organization will be a point of focus by exploring the limitations and the strengths of the system.

Research Questions

The main purpose of the study is:

- to define the degree of organization’s readiness to implement GSSs to a traditionally structured environment,

- to assess whether the application of GSSs will be a factor on the prevention of negative effects meetings may pose to productivity;

- to understand how GSS application will contribute to better levels of motivation, satisfaction, communication amongst members of the organization. In order to understand these dimensions, the questions presented below should be answered:

- What skills and abilities should employees possess to adjust to the new e-collaboration tools integrated by GSS environment?

- What are the main challenges of adjusting to computer-based environment?How can such dimensions as leadership, employees’ engagement, organizational learning and team building benefit from the integration of GSSs?

When it comes to the analysis of data, survey and study results are crucial in accurate measuring of the contribute to the group dynamics, commitment, motivation, and trust

Research Design

The case study will employ the use of focus group discussions with the organizational leaders and survey questionnaires with the employees.

Focus Group Discussions

Focus Group Discussion shall be conducted with the leaders (directors, supervisors, etc.) regarding their use of GSS in arriving at organizational decisions. The focus group discussion will tackle the following questions:

- To what degree e-collaboration tools are used as a primary means of communication within a virtually-supported team environment?;

- What training programs should be implemented to promote employee-engagement, team building, and leadership?;

- How do GSSs overcome the spatial and temporal dimensions?;

- How do GSSs contribute to the group dynamics, commitment, motivation, and trust?

Survey Questionnaires

Survey Questionnaires shall be disseminated to the employees via email about their views and insights of GSS use. Such questionnaires will find out the following:

- What skills and abilities should employees possess to adjust to the new e-collaboration tools proposed by GSS environment?

- What are the main challenges of adjusting to computer-based environment?

- How can such dimensions as leadership, employees’ engagement, organizational learning and team building benefit from the introduction of GSSs?

Secondary sources of information would be a thorough literature review covering all elements related to Group Support Systems.

Company Profile of Defense Health Agency (DHA), formerly known as Tricare Management Activity (TMA)

The Defense Health Agency, formerly known as Tricare Management Activity (TMA) was established on October 1, 2013. It is central to the governance reforms of the Military Health system (MHS) with the mission of achieving greater integration of direct and purchased health care delivery systems in order to accomplish the 4 aims of the Department, namely:

- achieve medical readiness,

- improve the health of people,

- enhance the experience of care and

- lower healthcare costs.

Conceptual Framework

According to the organizational theory, a company is presented as a group of individuals connected by specific objectives, mission, and statement (Cusella, 2009). This theory can also be applied to understand the aspects of efficient decision-making and problem solving processes (Koan, 2011). The framework also relates to the execution of the organization’s tasks, improving the satisfaction of all stakeholders and enhancing productivity. This is the study of the organizational processes (Cusella, 2009).

To enhance the understanding of how technology can promote organizational welfare, specific attention should also be given to the unified theory of acceptance (Brown et al., 2010). According to this theory, the role of GSS is confined to integration of technology acceptance and group collaboration. As soon as individuals adjust to a new environment, they will be able to understand what steps could be taken to transfer from a traditional communication model to a virtually-based environment. Readiness to change and accept novelties, therefore, is a priority. Appropriate tools and training programs are important for manipulating employee’s motivation (Pittinsky, 2009).

The acceptance theories is pertinent for understanding what stages employees should undergo to make a successful transition from traditional to a modern way of communication and collaboration. Along with organizational theories, the acceptance theory can allow manager to understand how technological gap can be fulfilled, as well as what potential benefits they can receive from this adoption.

The theory of organization shows that an organization is a group of people working together in a bid to accomplish certain set objectives and goals (Cusella, 2009). With this description, it is possible to argue that groups are vital as far as organization’s success is concerned. The given research will be instrumental in understanding the organization theory and how the GSSs are applicable within an organizational setting.

Definitions

GSSs stand for Group Support Systems. These tools support group processes that include brainstorming, voting, and group writing. GSSs are information systems that aim to make group meetings more productive and enhance the communication, deliberations and decision-making of groups by offering electronic support for a variety of meeting activities (Vreede & Muller, 1997). GSSs helps people to generate new ideas (brainstorming), to define concepts, to organize ideas into categories, and to evaluate ideas using various criteria and voting techniques. Groups can use a GSSs to perform activities such as project evaluations, strategic planning, work process analysis and design, crisis management, budgeting, and group training.

Assumptions

- Group challenges can be associated with leadership approaches to enhance collaborative group.

- Any leadership approaches can have both advantages and disadvantages.

- The negativity is the biggest challenge that needs to be addressed by the staff members who are eligible for these collaborative events.

- The theory of intergroup leadership is meant to address leadership in any collaborative organization.

- The role of a manager in an organization lies in developing new frameworks that can simplify the process of accommodation to a computer-based system.

Scope of the Study

This study will explore the consequences of the integration of GSSs on the efficiency of organizational meetings in various directorate levels of the DHA, Falls Church, VA. The study also aims to provide better understanding of how a new collaboration setting can contribute to the productivity and performance of an organizational team. In addition, the study will evaluate whether the GSSs application can compensate the challenges of virtual communication. Concepts such as leadership, organizational learning, and employees’ engagement shall be reassessed to suit new dimensions of success for motivating and increasing job satisfaction among the employees.

Limitations

Because the integration of technological systems is a relatively new phenomenon, estimation of its successful adaptation to the employed environment can be ambiguous. In addition, the case study of only one organization does not provide a full picture of challenges. Information gathered from the respondents of the focus group discussion and the survey questionnaires are delimited to their views and although they may represent the views of their own unit, the conclusion will not be generalized to the whole population of organizations that adopted GSSs.

Delimitations Rubric

Despite the emerged contingencies and limitation, the given research will provide a systematic evaluation of existing studies dedicated to the analysis of various skills, experiences, and models that are necessary for enhancing efficiency and reliability of collaboration, organizational learning and employees’ participation (Smith & McKeen, 2011). In this respect, specific emphasis should be placed on the role of information technologies into sustaining and developing new collaboration models.

Summary

In this chapter, and overview of GSSs is provided and how it may affect the effectiveness of an organization. It also presented the research problem that this paper will study and the methodology that will be employed for this qualitative research. The subsequent chapter Chapter 2 will discuss a thorough review of the literature on GSS and organizational efficiency. Chapter 3 will focus on the methodology that this study will employ including how data will be analyzed. The fourth chapter will present the findings of the study derived from the focus group discussions and survey questionnaires and interpret it. Finally, the fifth and last chapter will provide the conclusions and recommendations of the study.

Literature Review

The successful development of an organization depends on a plethora of factors that are specifically connected with structure, culture, and management mechanisms. The brief analysis of Group Support Systems (GGSs) has created implications for their further research to define how they influence the efficiency and overall performance. Integrating technology into an organization requires total reconstruction of business management. In order to accomplish the research, specific emphasis should be placed on several aspects. First, is necessary to examine various definitions of GSSs, as well as how they are applied in diverse fields. Second, it is purposeful to consider how GSSs can contribute to decision-making and conflict resolution in a global setting. Third, the paper seeks to assess the research studies dedicated to the analysis of the connection between technology and social environment to highlight the pitfalls of current management. Fourth, the examination of theories related to the group support system concept should be discussed. This is of particular concern to theory of acceptance and task closure theory that focus to the degree of interaction between a computer-based environment and social medium. Finally, the research will also refer to the connection between integration of support system and its influence on value creation, norms, and ethics. All these approaches are also premised on the constant interaction between virtual tools and collaborative environment ensuring support and flexibility to teamwork.

Due to the incessant competition, organizations are trying their best to curtail expenditures, augment the quality of their products, provide better customer service, and concentrate on their research and development (Akkirman & Harris, 2005). Important decisions are made in the organizations not individually, but in groups. This is followed in both the sectors; private as well as public (Matsatsinis et al., 2005). Healthy communications between team members can prove to be beneficial for the company because such communications increase the knowledge base of the employees and important information is shared (Woltmann, 2009). However, sometimes, due to the geographical locations of team members, such communication is not possible. Another problem with face-to-face communication is that each individual has very less amount of time to express his/her ideas and thoughts. This particular drawback is termed as air fragmentation (Bredl, 2009). Then, there is a possibility of supremacy by a single person. In addition, people are afraid to express their views because they are afraid that in case their ideas or thoughts are not up to the mark, other people will laugh and make a mockery (Wigert et al., 2012). Another reason for not expressing ideas is that individuals are of the opinion that if their ideas or thoughts are not liked by their superiors, they may be reprimanded and/or demoted. Earlier researches in this field show that in face-to-face meetings, almost 50% of the time is wasted. At this stage, the role of Group Support System becomes inevitable (Hayen et al., 2007). Group Support Systems can be explained as the tool that facilitates the communication between geographically distant team members or people through computer system (Kim, 2006; Pendergast & Hayne, 1995; Mennecke et al., 1992). Group Support Systems provide the organizations with various functions such as discussions, communications, data transfer, etc. (Ready et al., 2004). Such kind of a system permits individuals and organizations to categorize, assess, arrive at conclusions, and prepare for action (Vreede et al., 2003; Lewis & Shakun, 1996).

Title Searches

An array of information in the field of Group Support Systems was available. A review of available information contributed to the development of a historical overview of GSSs. This research focused on investgating how ready business organisaitons are for GSSs. The literature indicated different areas where GSSs is utilized. The evolving features of GSSs affects its variables. To identify GSSs variables, it was necessary to consider its evolving characteristics and to perform a historical review of the subject.

To derive the necessary literature, it was necessary to include various possible sources of information. This comprised peer reviewed journals from the school database. Google searches were also used to identify articles concerned with GSSs. Google Books was also contributed to the identification of necessary resources. Results from more than 300 peer reviewed journals and 22 books about GSS systems were generated. Articles were also collected from different company websites where real life application of GSSs is ontainable.

Group Support Systems

A brief evaluation of the GSSs has presented the term in the context of technological support that enhances project collaboration through integration of digital communication by means of various resources and tools (Brown et al., 2010; Hayward, 2010). However, there are many other alternative views on the scope and role of GSSs in an organizational setting. In particular, the studies by Ackermann and Eden (2011) have discovered that GSSs could be regarded as a representation of a cognitive theory due to their influence at all levels of organizational activities. In addition, GSSs have been employed to enhance negotiation of strategy making groups through an agreed direction. The scholars also insist, “…a GSS may particularly facilitate psychological negotiation within groups, supporting groups in reaching agreements about strategic direction” (Ackermann & Eden, 2011, p. 294). In order to understand the context within which GSSs are used, the focus should be made on a set of strategic interventions within a multi-national organization. This particular use of technology-based support system can allow group leaders to examine cognitive dynamics, namely how participants contribute to the agreement and information sharing between group members. Ackermann and Eden (2011) insisted that individual cognition shapes the underpinning for group negotiation as compared to the collective cognition. Although individual cognition prevents from understanding the role of GSSs in a group working, it is still vital to discuss them within the context of changing cognitions.

The importance of individual thinking is indispensable to evaluating how negotiation changes in the course of introduction of separate ideas and strategies. In this respect, GSSs build the means by which these changes are reflected. Jongsawat and Premchaiswadi (2011) also discuss the changing awareness in the research studies. Due to the fact that the group cognition is premised on the information the members operate during decision-making, group awareness indicates the readiness and availability of team while working on a particular project. In this respect, GSSs can be considered as tools by which the degree of group awareness is identified (Kolfschoten et al., 2012). Additionally, the system also serves as “an integrated computer-based system to facilitate the solution of unstructured of semistructured tasks by a group that has joint responsibility for performing the specific task” (Jongsawat & Premchaiswadi, 2011, p. 232). The main objective of GGSs; therefore, lies in achieving a final group decision with an effective agreement of needs and high quality of solutions.

Aside from the focus on computer-based environment, specific attention requires the role of social networks and face-to-face communication in changing attitudes of group members who enter a virtual space. In this respect, Smith and McKeen (2011) asserted that information technology system shape the basis of collaboration between team members that cannot access face-to-face communication. In this respect, GSSs can be presented as an ideal synergy of IT environment with the participants’ readiness to employ software for enhancing decision-making and communication. Such a perspective is also supported in Istudor and Duţă (2010) who refer to a GSS as to:

“…an interactive software-based system meant to help decision-makers to compile useful information from raw data, documents, personal knowledge, and/or business models and artificial intelligence-based tools to identify, model and solve decision problems” (p. 191).

Therefore, group decision support system requires a specific combination of software, hardware, people, and procedures.

With regard to the above-presented terms, GSSs embrace a range of important components, issues, and conditions under which people could effectively interact. Computer-based systems therefore, seek to support activities through interactive communication. Their quality is identified by the degree to which solutions are provided. Importantly, human factor contributes to the effectiveness of online communication in terms of the competence and experience of the team members in applying technological tools (Young et al, 2010).

Group Decision-Making and Conflict Resolution

With regard to the proposed decisions, the main role of GSSs lies in improving decision-making and conflict management in a team (Goh & Wasko, 2010). Such a function is especially important as far as the global setting is concerned because more and more organizations operate in a culturally diverse environment. Indeed, a virtual decision-making process gains momentum in the globalization process. The tendency also leads to collective problem management by employees whose mobility can be increased through web-based collaborative tools (Kerr & Hiltz, 1993).

Rapid and interactive decision-making are facilitators to the development of virtual team software and support systems as well as the promotion of efficient conflict management and improved problem solving (Huang et al., 2010). What is more important is that the integration of IT grounds contributes to proliferation of much faster and practical solutions proposed in an online setting through social networking platforms, micro blogs, and discussion forums (Hayward, 2010). In this respect, Turban et al. (2011) referred to a fit-viability models that assist in evaluating whether social software is suitable to a decision task orientation, as well as organizational development. The scholars find it vital to take organizational culture and structure into consideration because they affect greatly the readiness of employees to accept changes. Similar to Turban et al. (2012), Lee and Dennis (2012) have examined the connection between a decision-making process and GSS. In particular, the researchers have focused on the analysis of the various schemes and measures that should integrated in a software-regulated environment to ensure successful decision-making. In the course of the study, Lee and Dennis have concluded, “the participants in an IT-enabled group decision-making meeting can import from the already existing socially constructed world” (p. 21). Hence, the virtual reality can be identified with the face-to-face communication because it also implies interaction of individuals for the purpose of providing viable solutions.

Group Support Systems, as important sources of enhancing communication, provide a solid ground for reconstructing decisions. In fact, teamwork existing in a real life focuses on the decision-making as a prior action that any team should integrate (Goh & Wasko, 2010). However, traditional decision making in life setting implies a number of elements, including employed environment, cultural backgrounds, and employees’ needs. In the course of years, the evolution of group support into a technologically enabled network creates more challenges for sustainable operation. In this respect, Antunes and Costa (2010) support the idea that, “group support systems…are seen not only as a communication support, but also as a “decision-enabling technology, supporting debate, organization of ideas, simulation and analysis of consequences, and ultimately, enabler of decisions” (p. 198). Additionally, they are also recognized as media that enhance knowledge acquisition, quality of decisions, and employees’ motivation to participate in negotiation.

Certainly, working in traditional team environments has a positive influence on instant negotiation for various urgent issues. However, globalized approach to management implies developing new mechanisms that can solve the problem of geographical location. The growth of collaborative team has become a regular process in business organizations (Chandra et al., 2010). However, the introduction of GSSs has provided new alternatives for cooperating and group decision-making. Aside from enhanced communication, GSSs positively contribute to human resource management. In particular, Yao et al. (2010) emphasized, “GSS is able to facilitate HR groups to gauge users’ opinions, readiness, satisfaction, etc., increase HRM activity quality, and generate better group collaborations and decision makings with current of planned HRIS services” (p. 401). Hence, while introducing a technology-supported environment, the focus on employees’ needs and welfare remains a crucial point.

Recent trends in developing business organizations are predetermined by a globally driven realm that dictates new, software-oriented settings. The proposed research studies have concluded that GSSs are not only regarded as periphery systems enhancing communications, but as the main tools for establishing relationships between geographically alienated areas. In addition, the integration of GSSs into a business setting promotes human resource management and develops new strategies for decision-making and conflict management.

Advantages and Disadvantages of GSS

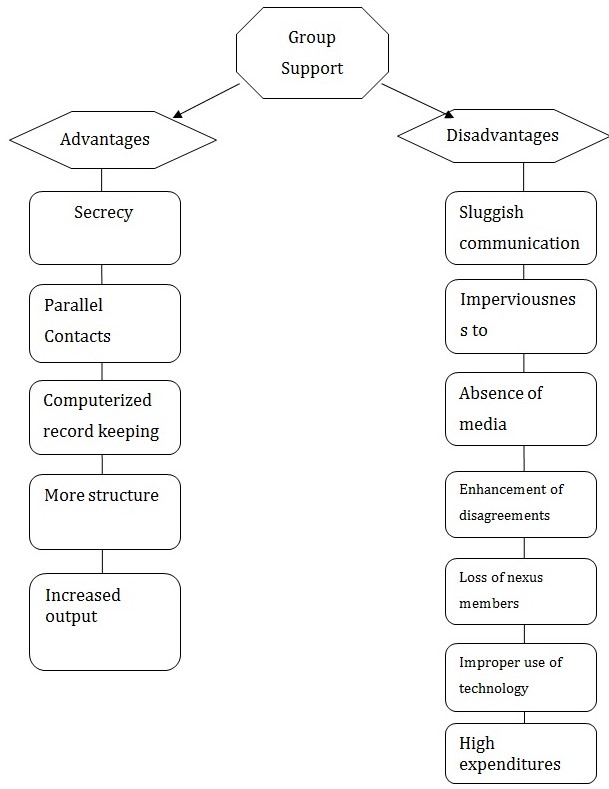

Group Support Systems are proving to be more and more famous because of the frameworks capability to improve group benefits and interface. GSS offer a plausible and engaging option to the customary face-to-face conferences and the management finds them to be beneficial, in light of the fact that conferences can frequently squander time or are inefficient (Aiken et al., 1995). Nonetheless, there are several benefits and drawbacks of group support system.. Figure 1 enlists such advantages and disadvantages of Group Support System.

Advantages

Group Support Systems have numerous advantages. Such advantages include secrecy, parallel contacts, computerized record keeping, more structure and increased output (Vreede & Brujin, 1999). Secrecy permits thoughts to be shared anonymously, which in turn boosts the level of confidence among people to participate in the process (Aiken et al., 1995). As a result of this provision of secrecy the members of the team do not have any inhibitions such as mockery by other team members. Another advantage is that the team members can give their opinions free from any fear of not following the manager’s opinion. It was found that over 80% of errands that included secrecy were about thought creation and it empowers the support of the team in the presentation of unpredictable thoughts (Pissarra & Jesuino, 2005).

In face to face gatherings, individuals should lend ears to what others talk and do not have time to ponder, however a Group Support System permits everybody to express their opinion simultaneously (Dennis et al., 2008). In conventional gatherings, each individual has just a couple of minutes to express thoughts, whereas Group Support System permits communication all through the conference. There is an augmented partaking and the conference is lively and fruitful. The conference is lively and fruitful due to the fact that the team members are allowed to use their thoughts in an unexpected approach. This is also crucial because each individual has his/her own level of intelligence and as such, various new thoughts can be generated (Aiken et al., 1995).

A Group Support System immediately records remarks, voting status, and other important data given by a group. Since there is automatic record keeping facility in GSS, the obtained records are automatically saved in an e-file (Aiken et al., 1995). The plus point in this kind of facility is that the team members or the managers need not carry hard copies of the records whenever and wherever required. They do not have to keep mental track of the proceedings (Bredl, 2009). In conventional aggregation settings members frequently neglect to fathom the narration of the speaker or on the other hand may be unable to process the information rapidly enough to contribute efficiently (Aiken et al., 1995).

Additionally, more composition and concentration is enforced into a conference that makes it tough, rather impossible, for the members to veer away from the concerned topic or problem. It is understood that the Group Support Systems minimize the distractions prevailing between teams that are functioning towards a common aim of completing any particular venture or assignment (Agres et al., 2005). This helps in avoiding rushed and imperfect assessments. This system also ensures more output due to the fact that the meeting concentrates only on a particular problem and as such, the time consumed is less – no deviations. It is a proven fact that the IT giant IBM was able to halve the time consumed in meetings. The aviation giant Boeing was able to decrease the total time consumed in various ventures by 90% (Aiken et al., 1995).

Disadvantages

Despite the fact that there are certain advantages of GSS, there are also certain disadvantages. Disadvantages consist of sluggish communication, imperviousness to transformation, absence of media sumptuousness, enhancement of disagreements, loss of nexus members, improper use of technology, and high expenditures (Elfvengreen, 2008; Hayen et al., 2007; Huber, 1980).

Individuals have distinctive studying styles and some take ideas or strategies at a relatively sluggish speed as compared to others. It is understood that there are certain individuals who cannot match their typing speeds with their verbal communication. There are also certain individuals who have insignificant keyboard abilities. Even though this particular disadvantage is gradually diminishing, it is still a hindrance during some specific meetings (Kerr & Hiltz, 1993). It is always advisable to employ a group support system for meetings of bigger magnitude. The point when the magnitude of the group is more than eight, the point of interest of analogous correspondence has a tendency to overshadow the detriments of constrained keyboarding abilities (Wigert et al., 2012).

People are usually extremely impervious to transformation, particularly pertaining to technology. Individuals are regularly threatened by workstations and feel debilitated when interacting with new individuals (Dennis et al, 2008). Employing a Group Support System includes preparing to utilize the programming and some individuals may be impervious to study how to utilize the framework. Managers at higher posts, who are most certainly not workstation proficient, are more inclined towards having a predisposition against utilizing the system while being more inclined towards using the conventional system (Aiken et al., 1995).

The Group Support System greatly depends on hard copies of information, and subsequently different types of correspondence are diminished. In conventional conferences, non-verbal communication and facial statements can assist other team members to have an idea about the reaction of any particular comment (Parker, 2011). Team members always favor face-to-face correspondence and as such the Group Support System can prove to be detrimental in making the conferences unfriendly and only related to the concerning problem (Ready et al., 2004).

Likewise there could be an enhancement in disagreements because of obscurity in the conference, since the comments of certain individuals might be critical. Members might abuse the system in light of the fact that the remarks are secret and one member could submit different remarks fortifying different members. This might make it appear that more individuals concur with a remark when they might be incorrect (Spiro, 2010). Additionally, individuals who want to command a verbal gathering might be less intrigued by contributing to GSS in light of the fact that they are unable to utilize their verbal aptitudes (Aiken et al., 1995). Be that as it may, bashful members are more probable to take an interest in the system and this inclination augments their participation (Spiro, 2010).

One of the main apprehensions with Group Support System programming devices is the expense which usually fluctuates between US $15,000 and US $50,000. This is particularly the scenario with Group Support System that is intended for utilization in a decision-room background (Kim, 2006). Hence, a substantial amount of money might be involved that might not be cost effective until and unless it is adopted on a regular basis by an organization. It is estimated that specifically crafted Group Support System cabins at the University of Mississippi had huge expenses – US $250,000. A smaller version of such a cabin could cost around US $90,000 (Aiken et al., 1995). Nonetheless, further improvements and upgrades in freely accessible e-collaboration have made numerous Group Support System aspects easy to access that involves no expenses or if at all there are any expenses, they are negligible (Pearlman & Gates, 2010).

Understanding the Gaps between Technology and Social Environment

Rapid integration of technological support in social environments has provided a new framework for operating within a business organization. In particular, the development of GSSs requires acquisition of new skills, experiences, and competences among the employees, which influence the effectiveness of their performance (Bredl, 2009). In fact, virtual teams do not cede the teams to negotiating in a real environment, except for a few issues. In particular, the employees communicating in a virtual space can be less encouraged to achieve trustful and motivated relationships (Cahalane, et al., 2010). The created gap can negatively contribute to further advancement of IT-enabled group support and management. In order to understand the problem, analysis of research studies should be introduced (Dennis et al., 2008).

The emergence of digital community is not a novel issue since the adoption of first technology-based models of collaboration date back to the second half of the past century (Mattison, 2011). In addition, Short (2012) introduced studies in which the focus is on the development and acquisition of new, alternative skills that expand experience in communicating at various levels. In fact, GSS technology substitutes a social context for brainstorming, problem solving, negotiation, and communication by means of an electronic environment (Chen & Kyaw-Phyo, 2012). In this respect, the assumption that virtual environment can create communication gaps is false. Rather, the scholars insist, “the main objective of GDSS is to enhance the process of the group decision-making by eliminating communication barriers, offering techniques for alternative’s decision analysis” (p. 32). At this point, GSS technology is advanced at information-processing dimension that largely depends on such characteristics as place, time, and synchronicity.

Collaborating technology and group-decision making is vital for entering a culturally diverse setting. In order to integrate this environment, employees must be provided with new tools and skills for collaboration (Chandra et al., 2010). However, the above-mentioned challenges have provided a number of limitations to integrating and developing IT-enabled communities in the workplace. In order to eliminate this gap, Kolfschoten et al. (2012) advised to consider two types of support: technology support and process support, both of which involve design task, application task, and management tasks. These three dimensions rely on associated roles and responsibilities imposed on the members of a business organization. In addition, Kolfschoten et al. (2012) introduced a framework for collaboration and technology-based support, group members should focus on such roles as development, application, and management of design administration. In particular, there should be a process designer, or a collaboration engineer, whose primary responsibility is confined to preparing the meeting process. Second, process application is another dimension that should introduced to collaborative activities. In this respect, a facilitator provides instructions monitoring the group members and assisting them in achieving the established objectives. At this stage, the facilitator should take responsibility for preparing and operating software, including the technical tools assembling the meeting facilities. Finally, management process should focus both on e-collaborative tools and on human resources involvement into the collaborative process.

With regard to the reviewed research studies, it can be concluded that, in order to fulfill the gap between technology and social environments, it is necessary to create a new alternative setting in which employees can improve their communication and develop new skills replacing and improving traditional means of group interaction. A specific framework proposed for this solution refers to three dimensions, including design, application, and management that should engage third parties ensuring successful communication and fruitful outcomes.

GSS Technologies

It is beyond any doubt that Group Support Systems are being employed by various organizations throughout the world. The organizations opt for the Group Support System because the GSS decreases the travelling costs, augments the adequacy of decision making and develops a working atmosphere where ideas are generated fast and there is innovation all around the work process (Bose, 2003). Organizations prefer such Group Support Systems that are economical, adaptable and can reconcile with their current information system (Bose, 2003). There are numerous aspects of computer aided interactions that influence the output of organizations pertaining to team attempts – a specific mention of e-coordination is eminent. The main aim of the Group Support System is to augment the adequacy and effectiveness of group collaboration by expediting the distribution of data between the team members (Goh & Wasco, 2010). PC interceded communication needs social habitations and influences the discernment and understanding of the significance of messages shared which makes the sharing of data around scattered teams somewhat troublesome (Kim, 2006). Because of the level of promptness of communication and absence of enough socio-zealous signs displayed in computer-intervened communication in contrast to face to face meetings, the time required for coming to conclusions is amplified and there is a disagreement between members that results in not reaching to any conclusion within the stipulated time (Andres, 2002). The inefficiency of PC-intervened communication to transfer socio-zealous matter in messages is discovered to incite lower fulfillment with the issue comprehending procedure (Andres, 2002).

Numerous collaborative tools are presently accessible with a wide array of characteristics and costs. Various GSSs are available in the global market like, Netscape’s Collabra Share, Novell’s Groupwise, Microsoft’s Exchange and Group Systems (Siau, 2004). It is necessary for business groups and people to identify their actual need and budget before opting for any GSS. These options now incorporate team underpin for the normal web client and could be connected to additional individual utilizations, for example family picture collections and family tree learning. Then again, organizations now have a wide assortment of choices for supporting group collaborations with PC-interceded devices for additional successful team actions and communications (Dennis et al., 2008).

Group Support Systems are amazingly favourable to business conglomerations, scholastic conglomerations, and other people. They are picking up acknowledgement as a viable PC based interaction instrument. Cooperation and decisions made by teams are a critical methodology inside associations and are promoted in scholastic settings (Bessiere et al., 2009). Teams that are topographically scattered can interact as though they were together at the same place concurrently. The conglomerations that at present utilize these frameworks are diminishing travelling expenses while augmenting output. New innovations and enhanced characteristics will lure conglomerations that presently do not utilize GSS networks so they can distinguish the plus points of this system. Since conglomerations have a global competition, Group Support Systems expedite correspondence (Schouten et al., 2010). This is a successful utilization of Group Support Systems.

The scholarly environment every now and again has scholars partaking in team ventures and identified communication. Alternatives are accessible to meet these cooperation ventures. They may be directed through message, inside a course administration framework, or with other considerably accessible, economical instruments (Young et al, 2010). The instrument that provides unsurpassed support is considered to be the superior one. In this way, scholars are presently confronted with numerous of the identical options in selecting that synthesis of characteristics which best furnishes collaboration for a specific learning atmosphere. Taking into account the pattern of a ceaselessly growing Group Support System instrument is tried and tested in this research, the hindrances to e-cooperation have been eradicated by several upgrades in the innovation. The true test now is the way to most effectively utilize such innovations (Wigert et al., 2012; Schouten et al., 2010).

There are several collaborative tools on the market such as WebDemo, Sametime, eRoom, Microsoft NetMeeting, Interwise, Groove, PlaceWare, WebEx, and GroupSystems (Hayen et al., 2007). All such programming devices offer numerous characteristics and advantages that may be convenient to a conglomeration hinging upon their necessities. The e-collaboration feature is accessible to any web consumer through websites such as Google (Google, 2013), MSN (Microsoft, 2013a), and Yahoo (Yahoo, 2013). Some of the plus points of a few major collaborative tools are examined in the ensuing paragraphs.

- Group Systems. Group Systems offer conceptualizing purpose and is particularly important in scenarios where obscurity, positioning, and voting are important. It permits all members to think and express outside the standard face to face frontiers and permits all people to participate in inventive or issue explaining targets instead of just a couple of features (GroupSystems, 2006). GroupSystems give structure and incorporate the extra feature of secrecy, when needed. Conglomerations utilizing Group Support System programming have saved almost half to three fourth of their expenditure and time as compared to the traditional face to face meetings. (GroupSystems, 2006). Undoubtedly, GroupSystems has some peculiar and vigorous features that make the use of Group Support Systems very easy and uncomplicated. Such features are not available in many of the other collaborative tools.

- Microsoft’s NetMeeting. Microsoft’s NetMeeting offers videoconferencing, remote desktop sharing, and added security (Hayen et al., 2007). Information encryption, client validation and password security are offered in order to guarantee security (Microsoft, 2013b). Sound and movie upgrades permit members to view other individuals and exchange thoughts and discussions. The whiteboard characteristic permits members to work together continuously with others utilizing realistic qualified data and the remote desktop imparting alternatives allows clients call a remote PC to enter its imparted desktop and provisions (Microsoft, 2013b).

- Groove. Groove is yet another Group Support System programming from Microsoft. Groove facilitates the convening of meetings and ventures and keeps a record of all the details pertaining to them (Microsoft, 2013c). Important qualified information for example statistics, records, messages, conferences, and forms are united in one place for everybody in the group to view. Allies inside the conglomeration and outside the conglomeration might be united and team members can dependably know the virtual area, or online vicinity of other team members which facilitates speedy discussion and coordinated efforts (Microsoft, 2013c). Additionally, every living soul can work with the same informative content if they are on the web, logged off or on a low frequency connection. Virtual teams cut across national, organizational, and functional boundaries, often resulting in diversity in team composition (Paul et al., 2005).

- Google’s Groups and Docs & Spreadsheets. The services expedite Group Support System e-coordinated effort for the normal Internet client, since this facility is furnished free of cost. In Groups, users develop a discussion board where other users can post their ideas. Clients post their comments, read others’ comments and enter into a discussion board if required. It is possible to make a discussion group open to all or limited to certain people only. In an open group anyone can participate in the discussion and post his/her comments. In a closed group, only the requested people have the authority to read and post comments. There are various categories available and each category has several groups. With Docs & Spreadsheets, clients have an imparted work region for their e-coordinated effort. They can upload files or other documents so that people in the group can see these files and documents and make any amendments if required. It is noteworthy that the required amendments in files and other documents can only be made if both the persons – one who has uploaded the files and/or documents and the other who is supposed to make the amendments – are online at the same time. This means that the files and/or the documents can be shared concurrently. This e-coordinated effort is conveyed without utilizing a web program. Google’s Groups and Docs & Spreadsheets are examples of Group Support System tools that can be accessed from anywhere via the internet.

Group Support Systems that give e-coordinated efforts have come to be standardized in the previous decade. This system is not accessible to only the bigger conglomerates. It is promptly accessible and extensively utilized by the normal web associated independent people as well. Nevertheless, this has additionally energized the development of Group Support Systems e-coordinated effort all through the organizations and today’s community. In the event that an organizational member is not utilizing Group Support System with any group related functions in the workplace or school setting, the group’s coordinated efforts may need to be re-evaluated (Google, 2013).

Interaction Between Computer-Based and Social Environments

The success of GGSs integration depends largely on the psychological and cultural factors. In particular, technology acceptance and recognition is the step toward successful penetration to e-collaborative dimension (Bakker et al., 2011). In this respect, specific emphasis should be placed on theory of acceptance and task closure theory that provide key steps toward gradual acquisition of necessary knowledge, experience, and skills (Owens et al., 2011).

In studies provided by Brown et al. (2010), attention is paid to technology acceptance as the starting point for developing mature group support systems. The concept of maturity implies the presence of models and frameworks that can be employed to a decision-making process. In particular, the researchers introduce the technology acceptance model that seeks to define “…specific classes of technologies that capture the nuances of the class of technologies and/or business processes” (Brown et al., 2010, p. 2). A set of issues constructs the technology acceptance model, including social presence theory and the task closure theory. The latter implies that the social presence and recipient availability constitute the key underpinnings for choosing a communication medium. The model also suggests that the above-presented qualities are significant for selecting a specialized tool for interaction because individuals express the need to bring closure to message sequences. Choosing an appropriate communication device will allow people to feel that they can efficiently achieve results while negotiating.

Aside from developing virtual collaboration, the basic function of GSSs lies in developing a social construction of meaning. Based on task closure theory, Chou and Min (2009) focus on the influence of media environment and group members on the relationship among breadth and depth of information sharing. The researchers also adhere to the idea that, “task closure theory is appropriate for explaining why a low social presence medium (such as electronic information sharing) paradoxically leads to high performance when dealing with fuzzy task” (Chou and Min, 2009, p. 428). Technology acceptance is largely premised on successful knowledge management and corporate software support system that facilitate strategic decision-making and enhance the competitiveness of an organization (Kimble et al., 2010). In fact, within the context of knowledge management, group support system can be regarded as consultation systems the employ artificial intelligent techniques to organize knowledge and make it available for decision-making frameworks. In addition, Trivedi and Sharma, (2012) represent Group Support System in a larger conceptual framework, along with Software Support System and Technology Acceptance Model to emphasize its significance for an organization. In particular, the researchers believe that successful implementation of GGSs is possible through consideration of psychological factors that make individuals accept various types of group support systems.

The awareness of reminiscent models of support systems, as well as technology frameworks for adopting theses systems, is another means for successful integration of IT-enabled technological environment. In fact, GSSs cannot exist separately from such dimensions as information sharing and exchange, knowledge management, and human factor (Koan, 2011). What is more important is that GSSs should correlate with other technology models, such as Software Support System, Decision Support System and Technology Acceptance Model (Richey et al., 2012). Finally, task closure theory is also indispensible to sustaining GSSs and creating a new social construct within an organization (Short, 2012).

Adaptive structuration theory

Another important theoretical aspect to consider in the study of GSSs is the Adaptive Structuration Theory (AST). The theory is developed from the hypothesis that group organisation is a function of social and task-based practices (Naik & Kim, 2010). Also, since Group Decision Support Systems may be analysed by focusing on the way groups utilise them, GSS based decision making is analysed within these contexts. The influence of GSSs on decision making can be analysed by identifying the systems that conform to GSS technology. These systems offer guidelines that groups can apply for structuring (Ghiyoung, 2014). Thus, while testable GSS based decision-making could be relevant, it is important to analyse the different structures to discern GSS based decision-making.

In their research, Gupta and Bostrom (2013) differentiate between aspects of technological systems. They identify ‘life’, which refers to the overall objectives and approaches that the system endorses (egalitarian decision systems), and the ‘specifics’, which refer to the systematic integration of structures into the organisational core (unidentified contribution of concepts) (Gupta & Bostrom, 2013). These GSS based decision making procedures are usually intertwined but frequently seem to oppose one another. Decision making systems that are GSS based have features that are based on the structuration theory. Structuration is a system development and redevelopment method, that is based on users’ conformity to rules, and application of available resources (Darshana & Gable, 2010).

A major aspect of the theory of adaptive structuration is group interaction, since it is the different social interactive procedures that recreate the applicable structural system (Jollean & Clinton, 2011). GSS based decision-making may be affected by any relative factor that influences member collaboration (such as organised creativity, task features, and deadlines). The appropriate application of GSS in decision-making may be identified through an in-depth analysis of group activities. The focus on the ways by which these groups employ and recreate technical and social systems will result in a clear understanding of the most effective approach for GSS based decision making (Jollean & Clinton, 2011).

It is possible to investigate appropriation from small group collaborations at a particular instance, when the GSS decision systems involved span long periods, and when they concern organisational and societal technology values (Sora, Kai, Min, & Hee-Dong, 2012).

In their research, Sora, et al. (2012) offer a viewpoint on GSS based decision making whereby both social elements and technology influence the group results, however only via influence on the structuring processes of the members. Most research studies on AST focus on how social elements and technology influence group appropriation procedures. For instance, Jollean and Clinton (2011) explained that social and technology GSS based decision making was less appropriate for conflict management when compared to the groups that were not exposed to the examined GSS based decision making procedure (Sora, et al., 2012).

Other research studies have identified variations in the effectiveness of conflict management between GSS based and manual decision-making procedures. Since individuals react differently when exposed to stimuli, it is obvious that GSS systems will influence groups differently (Sora, et al., 2012). In a similar conclusion, (Ghiyoung, 2014) explained that groups exposed to GSS based decision making procedures had a considerably higher level of agreement than other groups exposed to only instruction systems. Thus, adaptive structuration is a theoretical indicator of the significance of GSS based decision-making systems for organisational productivity.

Research Questions and Variables

The main purpose of the study is:

- to define the degree of organisation’s readiness to implement GSSs to a traditionally structured environment,

- to assess whether the application of GSSs will be a factor on the prevention of negative effects meetings may pose to productivity,

- to understand how GSS application will contribute to better levels of motivation, satisfaction, communication amongst members of the organisation.

GSSs are currently employed in almost every field. A review of historical, current, and future trends in GSS research will highlight the relationship between GSSs and the above mentioned variables.

Historical Development of GSS Systems

Decision-making remains the most significant element in management (Schacter, Gilbert & Wegner, 2011). Literature on GSS based decision making has frequently related the process to the intelligent design choice paradigm. The theory comprises of confined rationality (which insinuates that although it is possible to achieve a rational process of decision making, there are restrictions in individual intellectual processing skill under complex situations) and ―satisficing (indicating that even when the best decision is aimed at, confined rationality and restricted evidence could lead to endorsing solutions that are considerably feasible) (Javad, Ribeiroa & Varelac, 2014). Various studies on GSS based decision-making have been performed to eliminate these restrictions of fabricated complexity resolvers.

A considerable increase in processor-based computers was notable in the sixties (Hosack, Hall, Paradice & Courtney, 2012). The major application of this form of computing in business operations was the automation of repetitive business handling (Hosack, et al., 2012). At this time, computers were massive, costly, and had different specialized requirements for effective upkeep and utilization (Ghrabab, Saadbc, Gargouria, & Kasselb, 2014). It was complicated to create computer models and a person would require special programming knowledge to develop software that could accept data, and it was necessary for the programming to be performed on tape and created through a rigid collection of commands (Alkhuraijia, Liua, Oderantia, Annansingha & Pana, 2014). It was impossible for users to make any modifications to the process without the assistance of programming professionals (Alkhuraijia, et al. 2014). The implementation of these changes was time-consuming as a single modification could take weeks to accomplish. Although new functionalities were achievable after such modifications, the time and complexity associated with the modifications were rather annoying (Alkhuraijia, et al. 2014).

The emergence of minicomputers in during the seventies would result in an improvement in technology based management (Hosack, et al., 2012). The new computers were not as large and costly as mainframes, and required less upkeep. This made it possible for even small departments within firms to purchase computers, resulting in webbed computing systems and eventually to a group based decision-making procedure.

As companies began to utilise these shared computing technologies, other aspects of computer-based systems for decision-making research emerged in literature (Hosack, et al., 2012). Research studies focused more on user friendly and cheaper systems, than they did on monotonous systems. These ideas were the key premise the influenced the first research where DSSs was separated from organisational information structures (Hosack, et al., 2012).

Early descriptions indicated that DSSs focused on unregulated and semi-regulated issues, while information systems focused on less critical, organised issues including those backed by business handling structures. As history unfolds, it is apparent that GSS based decision-making systems still supports decisions that could initially have been unregulated and currently, due to a growth in in knowledge, are now more organised. During the seventies, focus on GSS based decision making emerged from the need to improve business decisions as complex unregulated and semi-regulated management decisions emerged as a major focus area of studies related to information systems (Hosack, et al., 2012).

Interactivity played a significant role in the development of GSS based decision making systems as it enabled instantaneous data analysis (Hosack, et al., 2012). The introduction of this method eased conflict resolution as it allowed the interactive troubleshooting and real time decision making (Eisa, 2013). This process therefore successfully eliminated unnecessary delays in the decision making process as. It was important to integrate data into GSS based decision making systems because group members required tangible data to effectively analyse and proffer solutions to the problems. Nevertheless, there was continuous evolution in the database systems and this led to new approaches for better database management. Research studies shifted focus to investigating the best methods of integrating database systems into GSSs to enable more tangible decision-making (Hosack, et al., 2012).

A review of different research studies within this period indicated that interpersonal communication was an issue most studies inadvertently focused on (Hosack, et al., 2012). The results of the research studies performed during this period showed that most GSS based systems were used to persuade or negotiate. The persuasion element of the GSS based decision-making process used data to indicate that an activity was either advantageous or disadvantageous. The negotiation element provided the opportunity for decision makers to begin by cutting down discrepancies or misinterpretations. Although these functions are considerable normal currently, it is important to note that GSS based decision making examination during the time was for aiding management decisions, and not for analysing data (Hosack, et al., 2012). It is obvious that users understood the opportunities availed by the presence of data, and harnessed these opportunities to suit their requirements.

Thus, it is possible to conclude that the idea of GSS based decision making was a result of the presence of communication and interactive technology, which was useful for managers facing ambiguous issues. Research studies on GSS based decision making combined technological advancement via database models and interactive technology with respect to the ambiguity problems.

Research studies in GSSs during the eighties integrated both technological development and an increased knowledge of decision-making. New hardware and software (such as the IBM PC and Electronic Spreadsheets) enabled interactive decision making amongst even group members without programming skills. Research studies at this point examined the internal processes used for developing the decision-making models. It was at this point that research studies focused on what is referred as group support systems. While the integration of these systems was advantageous, it allowed all users to come up with potential solutions to the problem at hand. This resulted in conflicts during corporate meetings. There was a need for new research studies to focus on possible ways of regulating GSS based decision-making procedures.

Historical research studies on GSS based decision making procedures principally focused on assisting decision makers by offering computer based aid during conventional corporate gatherings (Ghrabab, et al., 2014). The evolution of technology eliminated the need for participants to be in the same location during meetings, as video conferencing technology was developed and implemented. At this period, various research studies investigated the influence of information technology of GSS based decision-making procedures (Hosack et al., 2012). Research studies also focused on the group procedure, investigating variables, including leadership styles, and employee satisfaction (Ghrabab, et al., 2014). Intranet technologies were also developed in the same period as the wide spread of microcomputers. This led to another technological development and improvement in the knowledge of effective group decision making.

Group Support Systems and Group Decision Support Systems, are two phenomena that are rather complex to differentiate. For instance, Lindena (2014) refers to GDSS as GSS. However, GSSs are explained to include other variables such as design, interaction, intervention, dialoguing, and other responsibilities required for effective decision making within groups (Turban, Sharda, and Delen, 2011). In their research, Tow, Dell and Venable (2010) link the progress of individual to group support systems, which resulted in a system that was grounded on negotiation. The outcome of the investigation indicated that, executive ISs were a result of Group Decision Support Systems and resulted in data storage and internet based investigative processes, data sourcing, and for organisational intelligence systems.

The outcomes of Decision Support Systems are not always successful in spite of their application for the past forty years. Most of these letdowns are caused by inadequate planning, communication, and execution (Hosack et al., 2012). Although these systems are designed to aid the decision making process, it is important to note that the ability of the management to make informed decisions will also have an influence on DSS success or failure. Thus, GSS based decision making processes that are characterised by incompetent analysts will not be successful.

Poor implementation DSSs may also result in economic instability. The crash of the stock market in the eighties can be attributed to computerised systems that used the index as an indicator for trade automation (Yahiaa, Saoudab & Ghezalaa, 2014). However, it is important to note that humans permitted the computerised systems to control the trades and failed to place limitations on these systems or allow for human control.

The evolution of GSS based decision-making processes, in line with IT, is obvious from this historical review. However, these systems have not only enabled, but also restrict human activities. Technology only permits humans to perform possible gestures. This means it was not feasible to develop GSS based decision-making processes when humans could not easily communicate with computer systems. It was impossible for IT systems to support groups without the availability of network systems. With the continuous expansion and development of technology, it is obvious that more opportunities for GSS based decision-making will be continually increasing.

Present and Future Trends in GSS Research

The evolution process has seen decision support systems shift from a merely technological viewpoint to one that integrates data and knowledge (O’Learya, 2014). Apart from acknowledging the importance of data and knowledge in any system, it is important to understand their application. Different researchers have offered models that integrate DSS concepts beyond technological considerations (Pommeranz, Broekens, Wiggers, Brinkman, & Jonker, 2012; Wongsuphasawat, Plaisant, Taieb-Maimon, & Shneiderman, 2012).

There is a plethora of current research studies on GSS, and it will be a complex process trying to identify each research. However, it is important to note that these studies mostly investigate the significance of applying GSS systems in poorly organised decision-making procedures. Even though current technology is more efficient and accurate than historical technology, there has been a notable increase in the data availabity. The abundance of data means that organisations must ensure fast decision-making by responding to all evidence available. This makes it necessary for research to continue investigating the best ways to manage data for decision-making.

Research studies on information systems in the last three decades evolved through six paths: inter-organisational system study, Information Systems tactics, online software, Information Systems thematic studies, qualitative technique studies, and, most significantly from the viewpoint of this research, group support system studies (Dillon and Van Wingen, 2010).

It is important to consider the potential trends in the area of GSS based decision-making research studies. On a general note, future trends in the field are characterised by the integration of innovative approaches to data management.

Knowledge Management Decision Support Systems and Data Storage

We predict that the research streams of KMDSSs and data warehousing will merge, and the focus will incorporate better ways to allow organisational members to interact with available information, wherever and whenever it is available. It is likely that future research studies will focus on Knowledge Management Decision Support Systems and data storage will integrate, and the research will seek to include improved methods to facilitate remote interaction between group members, in real time.

This trend is obviously underway because a growth in decision making complexity and information accessibility will result in the need to align more logically based data systems with technologies that support the decision making process. This trend is already underway and is currently utilised by organisations such as Google and Amazon, hoping to improve their income through customer services that leverages data to assist clients make logical decisions.

Integrating KMDSS with data storage is an indication of organisations’ intention to focus on customer satisfaction. Previously, it took years to develop and integrate database storage systems with business operations. Current applications allow businesses to gather knowledge in a matter of seconds. This customer-based perception of organisational decision-making is closely related to the application of social networks and the way it influences individual decisions. People now consider the number of likes and followers a product has on Facebook and Twitter respectively, before deciding on whether to purchase the product. Mobile systems also influence the decision of consumers regarding a product or service. Some companies provide consumers with mobile shopping experience to enable them perform reviews of substitute products.

Data storing and KMDSS will always be a major area of research. Considering that majority of the research in this area will be technically inclined, it will be possible to examine improved processes for data recovery/categorization/operation, classification, and other procedural inventions to increase the optimal operation of storage systems, and the collaboration of the storage systems with other systems including Knowledge Management and Decision Support Systems.

Social Media Based Group Support Systems Based