Introduction

A banking system can be defined as an institutional network or group that is focused on providing financial services to people. Such an institution or group is responsible for providing individuals with investment assistance, as well as taking deposits and offering loans (Soskic 2015). Basically, a banking system controls the payment system in a given region. With the growing need to ensure the safety of banking activities within different markets, it has become important for countries to adopt a common trading currency, one that is acceptable in almost all countries in a given region (Eichler & Sobański 2012; Garrod & Mackay 2011). Such a system ensures that there is uniformity within the market as far as trading terms and rates are concerned (Hardin III & Wu 2010). According to Matsuoka (2011), a strong banking system depends on the strength of the banking structure adopted in a given market.

The Eurozone refers to a group of countries within the European Union that make use of the euro as their trading currency (Schäfer 2013; Tatarenko 2006). About 19 countries from the European Union make up the Eurozone. All of the members of the Eurozone have agreed to various regulations and supervision terms of the banking system (Schäfer 2013; Petrini 2011). On the other hand, in Switzerland—a country that is not a member of the Eurozone—the Swiss franc is the primary currency.

Following the global financial shock of 2008, decline in banking activities in Switzerland and the European Union was witnessed though the Switzerland’s recovery efforts were easy when compared to the case in the Eurozone (Soskic 2015). This was attributed to a number of factors such as Switzerland’s focus on domestic banking activities alone and hence, it did not face a credit crunch. Secondly, there has been a strong domestic demand in the midst of developments in housing markets in Switzerland unlike in the Eurozone. In addition, during this period exports showed a significant resilience to international headwinds. Lastly, effects on the massive appreciation of the Swiss franc were countered effectively by the monetary policy in Switzerland.

Therefore, it is worth analyzing the main reasons behind Eurozone’s profound crisis that was stronger than in Switzerland. For this reason, there is a need to examine whether or not there are any differences between the Eurozone and Swiss banking systems (Eichler & Sobański 2012). Such differences can be analyzed in terms of the regulation and supervision carried out for both banking systems. The rationale for carrying out this study is based on the need to establish whether the supervision and regulation of banking systems is dependent on a system’s structure or coverage. The choice of the two systems was informed by the fact that Swiss banking systems use the Swiss franc as the primary currency while all banks within the Eurozone use the euro. Switzerland is not a member of the Eurozone and hence, it was considered a perfect choice for comparison purposes.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the banking structure of the two systems, section 3 presents the leading banks while section 4 highlights the future of Eurozone and Swiss banking systems. Lastly, section 5 is a comprehensive conclusion of the paper and analyzes the differences in the two banking systems and presents a few recommendations.

Banking Structure

Banking structure refers to the format that is followed in a given banking system as far as order of activities and rank is concerned (Apergis, Miller & Alevizopoulou 2014). Different countries have different banking systems, implying that their banking structures are also different. For this reason, it is important to study the banking systems and structures of different markets so as to understand their general operations, which include the regulation and supervision of banking activities. In this section, a lot of emphasis is placed on the banking structures of Switzerland and the Eurozone in an attempt to compare the two for the purposes of establishing whether or not there is any significant difference.

Eurozone banking structure

The 2008 financial crisis had enormous effects on banking sectors worldwide, the Eurozone included. Since then, a rationalization process in the Eurozone area has reduced the operating credit institutions in the area (Garrod & Mackay 2011). A lot of pressure has been put on the credit institutions to ensure that they achieve the goals of restructuring and deleveraging the banking system in the area, as well as containing the increasing cost of banking (Apergis, Miller & Alevizopoulou 2014). For example, only 6,018 credit institutions were available in the Eurozone area towards the end of 2012 (Masciantonio 2015). In fact, there was a reduction of 592 credit institutions between 2008 and 2012. Only two member states of the region, Malta and Luxembourg, did not see reductions in their overall number of credit institutions (Garrod & Mackay 2011). On the other hand, Portugal, Greece, and Spain are on record as the countries with the highest decreases in the number of credit institutions (Igan & Tamirisa 2008).

A review of the resizing process in the Eurozone shows that in 2012, the banking sector held a total of 29.5 trillion euros, which represented a yearly decline from 2008 (Garrod & Mackay 2011). In spite of this, the Eurozone experienced a tremendous adjustment in 2009, which was based on the need to develop large banks in the area following the inception of the financial crisis (Apergis, Miller & Alevizopoulou 2014). With respect to gross domestic product, a wide difference is notable in the sizes of the banking sector assets among the members of the Eurozone (Masciantonio 2015). Most countries in the Eurozone have predominantly domestic assets as opposed to foreign asset control (Mody 2009). In spite of this, there is a substantial foreign presence in the area, which is characterized by bank subsidiaries that are under the supervision of the local authorities.

The banking system of the Eurozone depends on the European Central Bank, which carries out all of the region’s regulation and supervisory roles. However, members also have their own major banks that control banking activities at the national level. As noted earlier, there have been rationalization and resizing efforts in the Eurozone’s banking structure. Over the years between 2008 and 2012, a considerable evidence of enhancement concerning the efficiency of the banking system in the Eurozone can be traced, despite the fact that some countries depict cross-country heterogeneity (Igan & Tamirisa 2008). In addition, between 2008 and 2012, a notable decline of 8.7% was recorded within the Eurozone as far as the available local bank units were concerned (Garrod & Mackay 2011).

The central banks of all the Eurozone members are responsible for the European Central Bank’s capital stock. The activities of the European Central Bank are carried out in accordance with European law, although the structure of the bank has a close resemblance to a corporation’s structure. This assertion is based on the fact that the European Central Bank has the capacity of having stock capital, as well as shareholders. In addition, Eurozone banks adopted the Basel framework that provides regulations on minimum capital levels.

Switzerland banking structure

The financial sector of Switzerland is very large in comparison to financial sectors of many other countries of the world in terms of gross domestic product (Mody 2009). This sector is very important to the country’s overall economy and comprises a number of bank groups that have an extensive contribution to the overall position of the financial sector in the country (Fink 2013). The seven bank groups in Switzerland include the private bankers, the cantonal banks, the big banks, the foreign banks, the Raiffeisen banks, regional and savings banks, and “other banks,” all of which are controlled by the central bank in Switzerland, the Swiss National Bank (SNB). As such, the country’s financial structure originates from the Swiss National Bank, which has the mandate of the central bank. This bank has the capacity to declare other banks as systematically relevant based on their market capitalization value.

The Swiss National Bank started its operations in 1907 and currently has major offices in Zurich and Bern. Following the National Bank Act of 2003, the status of the SNB witnessed a tremendous change, as the act gave it a special independence status and allowed it to report directly to the public, the parliament, and the Federal Council (Fink 2013). Due to its position within the banking system of Switzerland, the SNB has the responsibility of designing as well as implementing the monetary policies of Switzerland. However, the primary duty of the Swiss National Bank is to ensure that prices within the market are stable at all times. As such, the bank plays a significant role in controlling the exchange rates in the area as well as taking care of gold reserves. For this reason, most of the activities undertaken by the SNB are geared towards the promotion of financial stability in Switzerland.

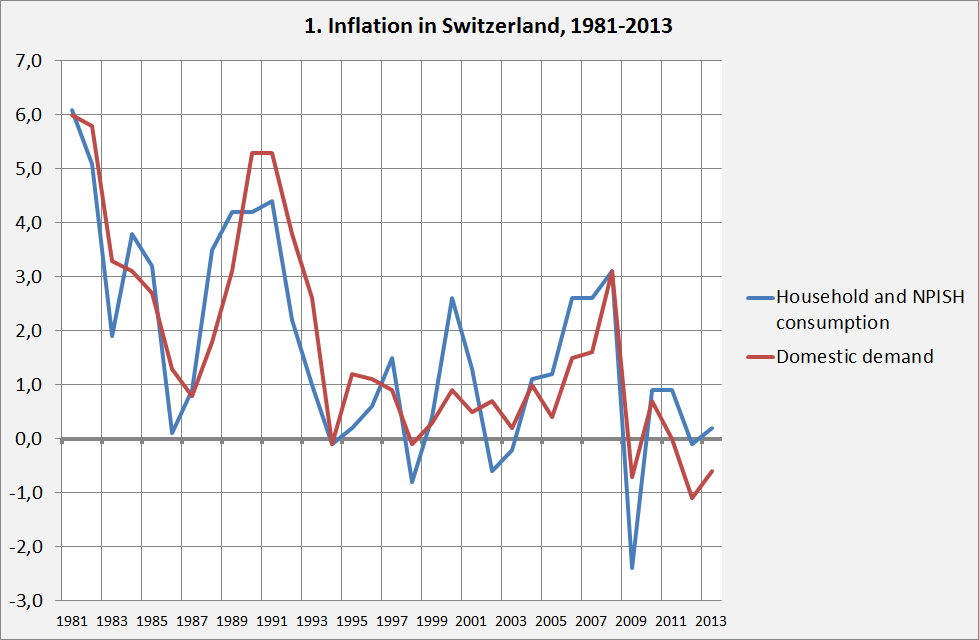

The monetary policy adopted by the SNB is designed to ensure that the country has stable prices at all times and that there is no inflation or deflation of price shocks. As such, the bank works on maintaining the inflation rate in the country at a margin of 2% each year. However, the country experienced a rate of inflation between 1981 and 2013 that had adverse effects, as shown below.

For the SNB to achieve its objectives in regards to the stability of prices, the bank sets out control measures aimed at maintaining balanced interest rates as far as short-term loans are concerned (Fink 2013). In addition, the Swiss National Bank takes care of the balance of the financial markets by monitoring and analyzing all financial situations to streamline conditions within the system that may have a negative impact on the integrity of the entire banking system. However, the Swiss banking system adopted the Basel framework that provides regulations on minimum capital levels. In spite of this, the central bank of Switzerland has a very important role in supervising the payment system of the country and its settlement systems (Fink 2013). In addition, the SNB is very instrumental in cases involving liquidity issues of other banks in the country whereby it offers lending services. On the other hand, the Swiss National Bank is also solely responsible for the issuance of Switzerland’s banknotes.

The chart below graphically illustrates the banking structure of Switzerland.

The private banking system in Switzerland is very important and focuses on universal banking, in which strong efforts are put on the provision of financial analysis, deposit business, credit and lending activities, and asset management services (Fink 2013). The significance of the Swiss banking system is that it works towards spreading risk across several businesses as well as customers in different economies. The presence of specialized banks in the country makes the entire banking system more suitable for a variety of customers since such an approach ensures that there are different options for people with different needs. For example, the big banks such as UBS and Credit Suisse are very significant in wealth creation and in the provision of expert services, innovation products, and various corporate services.

Eurozone versus Switzerland banking structures

The banking structure of the Eurozone and that of Switzerland are significantly different. Switzerland has the Swiss National Bank as the central bank, implying that it is responsible for most of the regulation and supervision activities (Fink 2013). On the other hand, while members of the Eurozone have their individual banks, they are actively monitored by the union through the European Central Bank (ECB). As such, the ECB is responsible for all regulation and supervision of the Eurozone banks (Tatarenko 2006). In addition, the introduction of the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) by the ECB was aimed at ensuring that the banks in the Eurozone experienced a change in the application of prudential supervision by providing supervisory standards and practices that are more harmonized and consistent.

While the Swiss National Bank is responsible for the monitoring practices of banks within the country’s borders, the European Central Bank is responsible for all the banks that are in the Eurozone. This shows that the banking structure of the Eurozone banking system is quite complex when compared to the Swiss banking system. In Switzerland, the numerous banks in the country have the freedom to make independent decisions regarding their trading activities. On the other hand, the banks under the management of the supervision of the European Central Bank lack such freedom. This explains why the member countries of the Eurozone have a lot of challenges whenever they face any financial crisis, since their devaluation decisions are determined by the Union. For this reason, the only way to save banks from such countries would be through internal devaluation, because devaluation of the euro is not an option for members of the Eurozone.

The SNB, which is the Switzerland’s central bank, holds the capital stock in the country, while in the case of the Eurozone, the independent members’ central banks are tasked with the responsibility of the capital stock of the European Central Bank.

Leading banks

Leading banks in Eurozone

The Eurozone area comprises of several member countries that each have individual banks. As such, the Eurozone has numerous banks that are very significant in the financial sectors of their individual countries as well as in the Eurozone as a whole (Zielińska 2016). Due to numerous challenges within the areas of operations, banks within the Eurozone have made substantial efforts to strengthen the banking system for the purpose of achieving reasonable recovery from the impacts of the financial crisis of 2008 (Garrod & Mackay 2011; Igan & Tamirisa 2008). Such an approach is based on the need to revitalize the credit base of the banks and attain a healthier economy (Mody & Sandri 2012).

A sizeable number of banks in the Eurozone have been very instrumental in the general performance of the economy of the Eurozone. For example, according to a review of the banking sector of the Eurozone, Banco Santander in Spain was considered the top bank in terms of market capitalization, valued at 114.9 billion USD (Statista 2016). This bank was followed by BNP Paribas bank from France, which had a market capitalization value of 93.4 billion USD. In third place was Allied Irish Banks (AIB) from Ireland, with a market capitalization value of 87.48 billion USD, followed by Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentarua (BBVA) bank from Spain with a market capitalization value of 72.22 billion USD (Statista 2016). Table 1 below shows a comprehensive summary of the top ten leading banks in the Eurozone according to statistics from 2014.

Table 1: Leading banks in Eurozone. Source: (Statista 2016).

From Table 1, it is evident that a considerable number of banks in the Eurozone have a market capitalization value of more than 50 billion USD, with only an insignificant number of the banks having a value lower than that threshold. Secondly, the table shows that the banks are spread across different countries in the Eurozone (Statista 2016). However, France, Italy, and Spain have the highest concentrations of leading banks in the Eurozone; indeed, two of the top ten banks in the Eurozone come from Spain, two from Italy, and three from France. On the other hand, Germany, Ireland, and Netherlands each have a single bank in the list of the leading banks (Statista 2016). Figure 2 below displays this same data in the form of a graph.

Leading banks in Switzerland

The banking sector in Switzerland plays an important role for the economy of Switzerland and is responsible for more than 5% of the total economic performance of Switzerland. In 2013, the sector recorded about 280 banking institutions, which represents an estimated decrease of about 4 institutions based on previous years’ records. This decrease was attributed to mergers, acquisitions, closures, and loss of bank status among some of the credit institutions in the country. There has been a lot of effort aimed at consolidating the banking system of Switzerland, with many of the same efforts continuing a few years after the financial crisis of 2008. During the following years, several acquisitions and mergers were witnessed that changed the structure of the banking system of Switzerland. In spite of this, there are several banks in Switzerland based on various groups that contribute to the financial stability of the country. Switzerland has several leading groups of banks that are designated by the Swiss National Bank based on a number of features. These bank groups include the private banks, foreign banks, Raiffeisen banks, regional and savings banks, big banks, cantonal banks, and “other banks.”

Cantonal Banks

Switzerland has about 24 banks that fall in the group of cantonal banks. The operations of the cantonal banks are primarily given to their assigned cantons even though there are cases when such banks open branches in areas that are away from their respective cantons. ZurcherKantonal Bank (ZKB) is one of the largest cantonal banks in Switzerland. Presently, the ZurcherKantonal Bank faces regulations and supervisions that are highly strict in comparison to other cantonal banks in the country due to the fact that ZKB is considered a significant financial group in Switzerland. The classification of cantonal banks as systematically relevant gives such banks the mandate to carry out organizational strategies and other necessary measures to guarantee all payment transactions in the event of insolvency threats.

The “Big Banks”

Switzerland has many banks, but only two are considered “big banks”: Credit Suisse and the Union Bank of Switzerland (UBS). These two banks are responsible for more than half of the total deposits made in Switzerland, a position that they have been able to achieve based on the fact that they have opened numerous branches in various parts of the country as well as in international centers. The Swiss National Bank considers UBS and Credit Suisse as systematically relevant. These banks have significant impact on the global business arena by offering various types of banking services to customers in different parts of the country and the world.

Regional and Savings Banks

In Switzerland, there are other banks referred to as regional and savings banks. As opposed to the operations of the other types of banks, the savings and regional banks in Switzerland have their emphasis on banking activities that involve savings and mortgage loans. Just as their name suggests, these types of banks cover relatively small geographical areas. In 2013, the country had a record of more than 60 banks under this category.

Raiffeisen Banks

Another category of banks in Switzerland is the Raiffeisen group of banks, which are operated based on a cooperative system of administration. These banks have branches in various parts of the country. According to 2013 records, Switzerland had more than 300 Raiffeisen banks, which in turn had more than 1,000 branches throughout the country. Of the seven groups of banks in the country, the Raiffeisen bank group is considered third in terms of size. This group has a lot of impact in classic retail businesses. For this reason, the Raiffeisen group is considered to be of systematic importance in Switzerland, a move that has led to stricter regulations and supervision as far as the group’s liquidity and capital issues are concerned. Additionally, a lot of pressure has been put on the organization of these types of banks for the purposes of maintaining the systematic importance of the banks in the event of impending bankruptcy cases.

Foreign Banks

The other category of leading banks in Switzerland is the group of foreign banks, which consist of banks having operations in Switzerland even though they are not primarily based in Switzerland. In addition, this category includes foreign banks that have full control of banks in Switzerland. Such banks have a lot of focus on the provision of services to foreign customers. However, the branches of foreign banks differ from foreign-controlled banks in that they lack the right to own legal entities since their control is based on the economic and legal frameworks of the parent company. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the organization of foreign banks is based on Swiss law even though they enjoy foreign controlling interest.

Private Banks

The private banking group is yet another category that contributes extensively to the financial sector of the country. Banks in this group carry out activities both inside and outside Switzerland with a lot of emphasis on asset management. These types of banks differ from the other categories of banks in Switzerland in that their legal structure is quite special and is based on limited partnership. This approach gives one of the partners the liability of his or her assets.

“Other Banks”

The other bank” group is comprised of banks that are in retail operations and are common in the country. For example, PostFinance is in this category, and it operates under a restricted banking license. Other examples of banks in this group are those involved in financial activities according to customers’ needs as well as those that do not have specific shared features.

Although there are in fact seven bank categories in Switzerland as highlighted above, UBS and Credit Suisse are the leading banks in the country. UBS was started in 1998 following a merger between the Swiss Bank Corporation and the Union Bank of Switzerland and is primarily operated from Basel and Zurich. In addition, the bank has several offices in major parts of the world such as London, as well as single offices in cities including Hong Kong and Tokyo. The other four offices are located in the United States of America. UBS is considered the largest, as well as the leading, Swiss bank. The second leading bank in Switzerland is Credit Suisse, which is based in Zurich and was founded in 1856. This bank plays a significant role in the economy of the country. For example, in 2007, the market capitalization of Credit Suisse was 95.2 billion USD. In addition, Credit Suisse has employed over 40,000 individuals. The major operations of the bank are on services in asset management, investment banking, and private banking. The Credit Suisse bank has had several successful mergers, such as the merger of 1988 when it engaged in the successful acquisition of The First Boston Corporation. In addition, in 1997, the bank entered into another merger with Winterthur insurance company.

On the other hand, the Swiss National Bank is very significant in the financial sector of Switzerland in that it has the mandate of the central bank of Switzerland. The SNB was founded under the Federal Act of 1906, with shares that are publicly traded as well as shares that rest in the possession of personal investors, cantonal banks, and the cantons themselves. It is illegal for the federal government of Switzerland to have any shares in the central bank.

The table below shows the number of Swiss banks.

Table 2: Leading Swiss Banks.

Eurozone versus Switzerland leading banks

The section above provided an in-depth analysis of the leading banks in the Eurozone and Swiss banking systems. The analysis was instrumental in highlighting the extent of the banking systems with respect to the major banks in the two regions. As evident from above discussion, each of the banking systems has its own leading banks based on the market capitalization value. First, it is evident that Switzerland has several bank groups that have a lot of impact on the financial stability and general state of the Swiss financial system (International Monetary Fund 2014). The Swiss banking system operates on a universal banking model. The implication for this is that the banks provide different banking services. The key services include lending, deposits, management of assets and advice on investment, stock exchange, underwriting, financial analysis, and payment of transactions. As outlined, the Swiss banks are divided into the categories of Big banks, Cantonal banks, Private banks, Regional and Saving banks, Raiffeisen banks, and Foreign banks. The groupings are according to the activities of the banks; thus, there is more specialization in Swiss banks, compared to those in Eurozone. The various categories are important in that they provide customers with a wide range of banking choices. In addition to the banks operating under the universal model, there is also a group of Swiss banks that specialize in stock exchange, securities, and asset management.

On the other hand, the banking system in the Eurozone is quite different from that in Switzerland for the reason that the banks are not based on groupings as in Switzerland. The banking system is based on the Eurosystem which is the monetary authority of the Eurozone. The principle role of the Eurosystem is to ensure monetary stability. The leading banks in the Eurozone have a market capitalization value of more than 50 billion USD. The banks are in different countries. This implies that centrality of services is offered by the banks to members of different countries. It ensures banking stability in the zone and that there are minimal differences in pricing of services. This varies from the Swiss banks, in that the price of services is influenced by the grouping criteria, i.e., services may differ, depending on the categorization of the banks (Tatarenko 2006). This is due to independent decision-making which the Swiss banks enjoy; hence, customers may experience huge differences in service provision. Despite the differences in services, it is worth noting that there are points of similarities between the Eurozone system and the leading banks in Switzerland, because market capitalization value and the level of strength is applied in the two systems.

The European Central Bank ensures that the banks within the Eurozone follow the required procedures, in terms of banking activities, according to the requirement of the European law (Zielińska 2016). On the other hand, even though the banks in Switzerland are independent in decision making, they are equally bound by the Swiss law and SNB’s monetary policies. The implication is that the two banking systems are very strict as far as the operations of the banks are concerned (Zielińska 2016; Tatarenko 2006). In spite of this, the Eurozone and Switzerland’s banking systems operate under different laws.

The Future of Eurozone and Switzerland banking systems

There have been numerous efforts and concerns as far as the banking systems of the world are concerned, many of which have been based on the need for stricter rules and regulations for the purpose of ensuring stability in the global financial system (International Monetary Fund 2014). For this reason, several proposals have been made towards a brighter future for the major banking systems in the world. A lot of focus has been placed on the Eurozone area given that it comprises many members, and therefore, the stability of the Eurozone economy is very important in the economy of numerous countries (Zielińska 2016). In addition, there have been concerns regarding the future of Switzerland’s banking system due to its location. For this reason, it is important to carry out an analysis of the banking systems of the Eurozone and Switzerland in order to determine their futures.

Future of banking in the Eurozone

There is a particular need for stable banking activities within the Eurozone given its importance among many countries. In spite of this, most of the largest banks of the world are experiencing market, regulatory, and political pressures that tend to have adverse effects on the stability of the banks in terms of capital and liquidity (Tatarenko 2006). For example, a number of banks within the Eurozone are facing the challenge of changing their business models based on the changing business environment witnessed nowadays in the banking sector. This is heightened by the fact that the European Union has been established; ensuring that strong and effective regulations are in place to govern the operations of banks from member states (Zielińska 2016). On the other hand, there is a lot of pressure from other players regarding the adoption of suitable banking structures that can be very supportive to the growth of the Eurozone economy.

Much effort is being put on ensuring a stable system in the region by focusing on measures that bring members together through the consolidation of the banking system and the establishment of effective regulation and supervision policies. As such, the Eurozone requires a banking system that is sound and safe (Zielińska 2016). Such a system can be achieved through the establishment of a banking union to take care of the needs of its members in terms of capital and liquidity.

The Eurozone banking system requires systematic reforms to achieve the intended level of safety and stability. One of the major problems affecting the banking system of the Eurozone is the currency union and its functionality (Tatarenko 2006). Numerous concerns have been raised over the use of the euro, primarily based on the diverse economic levels of the countries forming the Eurozone. In addition, there is a need for reform based on the insufficiency of economic development among several member countries (Zielińska 2016). This issue is often made worse by the fact that member countries have limited responses to economic shocks since they are not allowed to devalue their currencies (Zielińska 2016). Also, the Eurozone banking system currently suffers from the problem of intergovernmental governance due to the fact that the core state powers are affected by the Economic and Monetary Union. For this reason and to avoid a possible collapse of the entire system, there is a need for a system whose governance does not have negative effects on the core functions of the member states.

The Eurozone is still recovering from the effects of the financial crisis of 2008. The fact that the euro area comprises numerous states makes such effects especially significant in regards to the overall position of the entire banking system (Schäfer 2013). There have been many instances of crashes in the prices of bank shares, as well as increased bond yields, low growth rates, persistently high debt in the private and public sectors, and expansionary fiscal policies (Tatarenko 2006). Even though there had been promises of effective measures aimed at protecting the Eurozone members from speculative attacks, such promises have not been achieved, especially considering that the end of the initial stage of the crisis within the Eurozone was accomplished at the cost of several Eurozone members. As such, the area has been faced with the urgent need to find and implement a lasting solution to the structural problems affecting the regional banking system.

In recent years, the Eurozone has suffered enormously due to pressures from the Economic and Monetary Union regarding the welfare and national labor markets of members. Such a challenge affects regional fiscal policy, leading to reduction in social expenditures, which in turn significantly increases pressure on the members’ welfare (Tatarenko 2006). The future of the Eurozone banking system comprises of lasting reforms in the banking sector that focus on the formation of social and political foundations based on the common currency. For this reason, the future of the banking system in the euro area ought to emphasize the creation of a Eurozone budget as well as an automatic stabilizer. This is instigated by the need for an increase in the Eurozone’s level of flexibility toward member countries should there be a lack of adjustment based on the national monetary policy (Zielińska 2016). Secondly, the introduction of insurance-based mechanisms can be very instrumental in serving as automatic stabilizers alongside suitable fiscal policy. The adoption of such a strategy is based on the fact that Eurozone insurance often balances the economies of different members.

Future of banking in Switzerland

The banking system of Switzerland has undergone tremendous transformation following the financial crisis of 2008. In spite of the fact that there were numerous challenges during the years immediately after the financial crisis, Switzerland has made noticeable improvements in its banking system in terms of stability (International Monetary Fund 2014). The income collected from services and other commissions were responsible for more than 40% of the total net income. In addition, the banking system in Switzerland also received an increase in the interest-earning business. Overall, there was a significant increase in the net profit from major banking services in Switzerland in 2013 as compared to previous years.

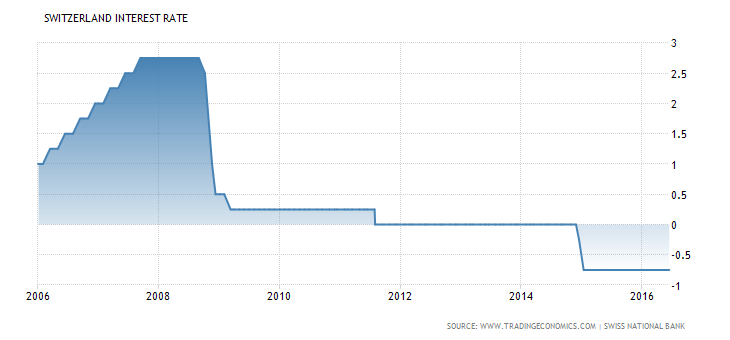

In spite of the rise of net income in 2013, there were low expectations that similar cases would occur in 2014 and the following years. Partly, this attitude was attributed to the fact that there was a continuous stream of low-interest margins (Zielińska 2016). Nevertheless, there was an increase in the transaction volume of the Swiss stock market in 2013. In addition, a high securities value was noticed in customer custody accounts, although there was a decline in structured products in 2014 (Tatarenko 2006). Based on these observations, concerns have been raised regarding the possibility of low interest rates remaining the same for a considerable number of years, especially in the case of interest-earning business (Tradingeconomics 2016). Given that the interest-earning business aspect is a significant contributor to the net income of banking systems, there is a high possibility of constant low interest rates for several years in the future, as shown in the figure below.

Additionally, the banking system of Switzerland is likely to face a lot of competition from neighboring systems, which is likely to have adverse effects on the overall income (Tradingeconomics 2016). On the other hand, chances are high that stricter regulation will affect the banking system of Switzerland negatively in terms of cost.

As such, several challenges are in play that will have an adverse effect on the future of the banking system in the country. For example, Zielińska (2016) observed that the presence of uneven global economic development, as well as the unresolved fiscal issues within the Eurozone, has a high possibility of reducing the banks’ profitability in the area.

A comparison between the future of Eurozone and Switzerland banking systems

The review of the two banking systems pointed to some inherent differences and similarities. For instance, the aspect of market capitalization is a key similarity between the banking systems, which influences the stability of the banks. The past occurrences, such as the financial crisis of 2008, adversely affected the banks both in the Eurozone and in Switzerland. For example, the crisis weakened several major banks and led to the closure of others (Zielińska 2016). This shows the need for the systems to be based on stiff banking regulations and strategies that will help them overcome similar challenges. Even though the two banking systems were adversely affected by the crisis, the inherent differences in the banking practices affected the ability of the banks to cope with the crisis. For example, given that the Eurozone includes numerous banks from its member countries, the impact of the financial crisis of 2008 was higher than in Switzerland.

Additionally, the presence of a common currency used by all the members of the euro area has many disadvantages compared to the single currency of Switzerland. This disadvantage stems largely from the fact that a devaluation of the currency is not possible for individual banks or countries within the union. For example, the bankruptcy of major banks in the Eurozone led to instability in the financial sector in their countries and the euro area in general (Petrini 2011). In spite of this, devaluing the euro on a national basis was not an option, since the euro is used by numerous other countries. Devaluation of the euro in one country would have affected the rest of the countries in terms of financial stability and stock capital (Schäfer 2013; Petrini 2011). The implication of such a system is that only the financially stable banks in the Eurozone have the upper hand in case of crisis. On the other hand, the banking system of Switzerland depends on the Swiss franc as the common currency and has little to no external pressure.

However, Switzerland has numerous challenges presently resulting from increased competition from the neighbors, as well as the continuous decline of the country’s interest rates. Such a scenario is likely to affect the stability and general position of the banking system in the future (Petrini 2011). In the case of the Eurozone, there have been a lot of concerns about the rules and regulations that govern the members’ banking activities and decisions. For example, the fact that members of the Eurozone cannot devalue their currency has a negative impact on the future of the Eurozone, since several members are contemplating withdrawing from the Eurozone, such as Greece and Britain. Although the two banking systems were affected by the crisis, the Swiss banking system did better after the crisis. This is attributed to the independence of most of the banks and hence, ability to draw regulations that helped them to mitigate the effects of the crisis faster than the banks in the Eurozone. In addition, it was convenient to effect austerity regulations at country level rather than regional level.

From the above observations, it is evident that the banking system of Switzerland has a brighter future that the Eurozone’s since challenges facing the banking activities can be solved internally, unlike in the case of Eurozone banks.

Conclusion

The focus of this study was on carrying out an analysis of the banking systems of the Eurozone and Switzerland to ascertain whether or not the two systems are different in terms of regulation and supervision. From the analysis, it is evident that there are similarities and differences in the Eurozone and Switzerland banking systems, both of which have a considerable impact on the regulation and supervision of the individual systems. The major differences and similarities in the two systems can be traced from the systems’ banking structures, leading banks, as well as from the future of the banks.

Differences in the two systems in terms of the banking structure are brought about by the fact that in the euro area, there are numerous countries that use the euro as their common currency for all their transactions, while banks in Switzerland use the Swiss franc as their primary currency (Tatarenko 2006). To some extent, the use of a common currency by numerous countries is quite disadvantageous to some members, even though it can also have significant benefits. For example, such a system makes it hard for the member countries to devalue the euro in case of a financial crisis, since devaluing the common currency would affect the competitiveness of the exports and imports of all member countries. The implication in this case is that the decision of one member country regarding the value of the common currency is insignificant. However, the use of the euro as the common currency eliminates the exchange rate costs and fluctuation risks.

Within the Eurozone, regulation is carried out by the Union, while the Swiss banking activities are regulated and supervised by the Swiss National Bank. The union-based regulation is quite disadvantageous in that it assumes a blanket treatment of banking activities for all members hence, adversely affecting some members.

Secondly, the study found out that Swiss banking sector is divided in terms of groups, with the leading banks being referred to as the “big banks.” The leadership of the banks in the two systems is dependent on the market capitalization of each of the banks. However, in the case of the Eurozone, leading banks are defined with respect to the performance of other banks from all the members of the Eurozone. The availability of numerous bank groups in Switzerland offers individuals with suitable alternatives for domestic banking.

Thirdly, according to trends, it was evident that the future of the two banking systems is strongly linked to past occurrences and present strategies. For example, the analysis has shown that the Eurozone and Switzerland were hard hit by the financial crisis of 2008 that weakened their individual trading currencies significantly. In spite of this, the two systems adopted various measures to regain their financial position, including bailing out countries that were facing the threat of bankruptcy. However, Switzerland is facing the challenge of low interest rates and competition from other banking systems, while the Eurozone suffers from the challenges to weak members’ economic and financial sectors, as well as members withdrawing from the euro. Basically, the banking system of Switzerland is in a better position, with respect to the numerous challenges affecting the banking activities within the euro area.

From the foregoing, it suffices to say that the banking system of the Eurozone and that of Switzerland are significantly different. Despite the cited differences, there is need for suitable measures that can control and monitor the banking activities in the two systems to ensure favorable interest rates and competitive imports and exports, as well as effective terms of common currency to avoid future conflicts that would necessitate withdrawal of members. In addition, the banking structure of the systems requires improvement to allow for effective regulation and supervision. For example, the laws and regulations governing the operations of the European Central Bank need to be revisited to provide the necessary independence for all banks within the Eurozone, with respect to their position in the Union. Such an approach would ensure honesty and transparency among member countries and banks in relation to their banking activities.

References

Apergis, N, Miller, S & Alevizopoulou, E 2014, ‘The bank lending channel and monetary policy rules for Eurozone banks: further extensions’, The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, vol. 1, no. 1, pp.23-24.

Eichler, S & Sobański, K 2012, ‘What Drives Banking Sector Fragility in the Eurozone? Evidence from Stock Market Data’, Journal of Common Market Studies, vol. 50, no. 4, pp.539-560.

Fink, A 2013, ‘Free banking as an evolving system: The case of Switzerland reconsidered’, The Review of Austrian Economics, vol. 27, no. 1, pp.57-69.

Garrod, D & Mackay, A 2011, ‘Extension of Crisis-Related State Aid Rules for Banks as Eurozone Economies Continue to Lurch’, Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, vol. 2, no. 2, pp.135-137.

Hardin III, W & Wu, Z 2010, ‘Banking Relationships and REIT Capital Structure’, Real Estate Economics, vol. 38, no. 2, pp.257-284.

Igan, D &Tamirisa, N 2008, ‘Are Weak Banks Leading Credit Booms? Evidence From Emerging Europe’, IMF Working Papers, vol. 8, no. 219, p.1.

International Monetary Fund 2014, ‘Switzerland: Technical Note-Stress Testing the Banking System’, IMF Staff Country Reports, vol. 14, no. 267, p.1.

Masciantonio, S 2015, ‘Identifying and Tracking Global, EU, and Eurozone Systemically Important Banks with Public Data’, Applied Economics Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 1, pp.25-64.

Matsuoka, T 2011, ‘Monetary Policy and Banking Structure’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 43, no. 6, pp.1109-1129.

Mody, A 2009, ‘From Bear Stearns to Anglo Irish: How Eurozone Sovereign Spreads Related to Financial Sector Vulnerability’, IMF Working Papers, vol. 09, no. 108, p.1.

Mody, A & Sandri, D 2012, ‘The Eurozone crisis: how banks and sovereigns came to be joined at the hip’, Economic Policy, vol. 27, no. 70, pp.199-230.

Petrini, C 2011, ‘European regulations on cord blood banking: an overview’, Transfusion, vol. 52, no. 3, pp.668-679.

Schäfer, D 2013, ‘Banking Supervision in the Eurozone’, Intereconomics, vol. 48, no. 1, pp.2-3.

Soskic, D 2015, ‘EU Banking Union: Lessons for Non-Eurozone transition countries’, Industrija, vol. 43, no. 2, pp.164-181.

Statista 2016, Euro area banks by market capitalization in 2014, Web.

Tatarenko, A 2006, ‘European Regulations and Their Impact on Tissue Banking’, Cell and Tissue Banking, vol. 7, no. 4, pp.231-235.

Tradingeconomics 2016, Switzerland Interest Rate 2000-2016, Web.

Zielińska, K 2016, ‘Financial Stability in the Eurozone’, Comparative Economic Research, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 25.