Introduction

During the last couple of years, young innovative entrepreneurs have garnered substantial attention from different sectors of the economy. This attention stems from the view that governments have realised that small businesses account for a significant amount of innovation, economic growth, and a source of job creation. Hence, most economies and policymakers are turning attention to finding either direct or indirect methods of financing such businesses. The lack of finance for innovative young businesses is real and it has a widespread view as an ever-occurring theme.

Lack of finances for small innovative firms stems from the perception that start-up newness in the market and missing records of accomplishment is associated with high risk by most financing entities. Therefore, most financiers are sceptical to provide funding since they perceive these firms as having high default risk. Consequently, most young innovative firms are pushed into financial constraints as opposed to other large firms, thus restraining their development and potential future growth. The area of financing small innovative firms has enjoyed significant interest from scholars as an area of study over the years. These studies mostly deal with start-up financing from the supply side focusing on business angels and venture capital. Therefore, this study aims at exploring start-up financing for small innovative firms by looking at options available and approaches in financing small firms.

Theoretical framework

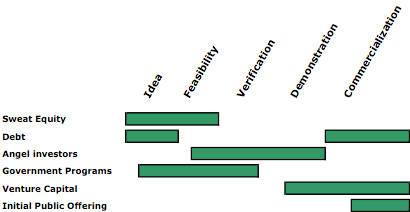

Most studies on financing start-up innovative businesses explore venture capital, business angels, and financial bootstrapping. Investment phases are split into three stages, viz. planning, search, and evaluation and negotiation. The first stage involves small innovative entrepreneurs’ activities related to searching and screening to take due diligence before accepting the financing. Secondly, the investors consider negotiation terms and conditions by evaluating the value of the firm. The third stage involves post-investment activities that take place after an agreement has been accepted including the management of future financing, coaching of young entrepreneurs, and exiting. Angilella and Mazz (2015) explored investment decisions mostly involving women entrepreneurs from the perspective of demand and introduced another perspective. This study split financing start-up innovative business into four parts viz. search, negotiation, planning, and post-investment. Therefore, this literature has incorporated Angilella and Mazz’s (2015) proposal by adding a fourth component, planning.

Planning involves activities undertaken before a decision is made on the mode and ways of external financing. It involves the preference for and approaches used by various funding sources. Most scholars associated venture capital and business angels with the agency theory perspective. Ozioma-Eleodinmuo (2015) posits that in agency theory, the entrepreneur is more informed compared to the investor (principal). Therefore, the principal’s role is to ensure they mitigate risk by seeking innovative ways of overcoming risk. According to Goli (2014), venture capital and business angel differ in their approaches to minimising any possible losses from an investment. Goli (2014) adds that business angels mitigate uncertainty through primary ex-post control. In other words, it is referred to as an incomplete contract approach. Wray (2012) notes that both venture capital and business angels differ in their approaches to investee firms, thus supporting the convergent view from other scholars. Business angels seek to exercise control over investment activities and assistance through information asymmetry.

On the other side, venture capitalists primarily use terms in the shareholders’ agreement such as forming an investment board to control the investee firms. Balzs (2014) interviewed over 100 founders of big companies and fast growing private businesses in the United States to determine the most appropriate way of raising capital for small innovative companies. The results from these interviews revealed that in most business start-ups, bootstrapping is the main financing option used. Bootstrapping is financing start-up businesses through a highly creative acquisition of finance without using external financing. Alperovych and Hbner (2013) argue that bootstrapping involves high reliance on credit cards, second mortgages, customer advances, and retained earnings. About 80 per cent of start-ups are financed through credit cards and personal savings (Balzs 2014). Raising start-up capital has become a pertinent problem that needs to be addressed since entrepreneurs waste a lot of brainpower trying to raise money by courting investors. Some entrepreneurs believe that a business should first raise big money. Politis (2008) argues that if venture capitalists fail to accept a business plan, entrepreneurs switch to business angels. Many young innovative businesses are disappointed when their offer is rejected by venture capitalists as shown in the following graph.

Nienhuis, Cortet, and Lycklama (2013) stress that most young innovative businesses fail to qualify for venture capital not because their business is scrappy, but because they do not meet the criteria for qualifying for venture capital. Venture capital criteria are exacting since they incur a significant amount of financial costs in investigating monitoring and negotiating investment deals (Cressy 2009). Venture capitalists can only finance a few entrepreneurs since they know that some start-ups will yield negative returns.

After many years of seeking venture capital, the ImmuLogic founder learned that the entrepreneurs’ time is wasted trying to court investors in most cases. After one year of seeking venture capital with a well-written business plan, Lutz and other partners contributed $12,500 to finance Gammalink. After a few years after the start-up, it attracted $800,000 unsolicited venture capital (Bhide 1992).

Internal financing and bootstrap financing

Internal sources of finance include retained earnings, savings, credit cards, and second mortgages. While many people would opt for venture capital and angel financing, Vasilescu (2014) believes that start-ups typically lack or cannot meet the standards stipulated by some venture capitalists. In most cases, venture capitalists prefer businesses that they perceive to be highly profitable not only in the short term but also in the long term. Venture capitalists may even reject small start-ups with impressive business growth capacity because sometimes even high return does not cover their investment overheads (Rossiello & Parris 2009). Moreover, they fear that small innovative firms like likely undergo market failure even before making enough profit to pay back their money. They prefer products that attract million-dollar markets. Zinecker and Bolf (2015) rue that venture capitalists might reject businesses likely to change the world. Small start-up businesses start with impressive business ideas to achieve a sustainable competitive edge by introducing a brand name.

Most start-ups venture into sectors that are highly risky even before they gain the capability to evaluate risk and returns effectively. On the other hand, investors prefer businesses that are less risky in a well-defined market. Bootstrapping requires a different mindset as opposed to just relying on basic principles and practice that will not help entrepreneurs. Small businesses can also start operating with limited finance. However, founders require a different approach than just launching a software venture. Managers cannot reap the benefits if the business remains marginalised. Opportunities usually turn up when a business is in operation, which would not have been realised without operation. For instance, the Compaq Computer venture was originally financed through bootstrapping. Canion Harris and Ben Rose contributed $20 million in start-up, which has enabled the company to enter the market effectively like other big players. In the first year, the total sale was more than $100 million (Ramadani 2009). Chemmanur and Fulghieri (2014) argue that to succeed in bootstrapping, financing founders should minimise investment in physical assets during the development and set-up stages. To overcome start-up financial challenges in bootstrapping, the venture must offer high-value products that can sustain direct personal selling. Balzs (2014) argues that getting customers to give up their loyalty to a new brand is one of the most complicated exercises that entrepreneurs have to overcome. Many start-ups might underestimate marketing costs expected to overcome customers’ inertia, especially concerning impulse goods. For instance, launching a new packaged food product in the market today without enough marketing capital would futile endeavour. Building a successful business means persuading many customers to try your product. Without sound marketing research, advertisement and promotion mechanisms marketing impulse goods would be futile. Therefore, innovative entrepreneurs often pick high-value products and services that they are willing to go the extra mile to finance effectively.

Why sources of financing small innovative firms are changing in the UK

Today, most economies have realised the significant contribution made by small to medium size businesses. The UK is not an exception, as small innovative businesses are a source of economic growth and job creation in the region. According to Revest and Sapio (2012), small innovative businesses create about 17 per cent of total jobs available per annum in the UK. Similarly, in Canada, small businesses account for more than 90 per cent of all businesses in the country and employ over half of all Canadian working class in the private sector (Revest & Sapio 2012). The UK government dramatically changed its policies toward small innovative businesses by putting in many resources to boost the SMEs sector. Policymakers are now turning to small innovative businesses since they are critical to the wellbeing of the UK economy. Many governments are supporting small innovative businesses directly or indirectly through financial means. The UK government has introduced initiatives to support SMEs by introducing policies such as reduced business taxes, increasing direct support through mentoring, and resources to encourage small innovative businesses to thrive.

Earlier businesses depended on banks and other external financing channels, which are in most cases unwell to finance risky small business start-ups. However, with the government introducing alternative sources of financing small businesses, banks will lower interest rates to woo SMEs. The UK government appreciates that small businesses are the cornerstone of a growing economy, and thus supporting young entrepreneurs is critical. According to Dahlman and Aubert (2010), this initiative intends to protect small businesses from the substantial increase in the EI premium rates. The government intends to ensure long-term stability and predictability of jobs in the UK. However, critics argue that government subsidies cannot effectively solve market failures of small businesses. In fact, businesses are affected by complex environmental conditions such as negative externalities and information asymmetric.

Barriers of financing innovative small businesses in the UK

In the UK, the government has introduced major initiatives to finance innovative small businesses. However, banks remain the biggest supplier of SMEs finance. Barriers to financing small innovative businesses stem from the fact that financing is influenced by funding preferences such as risk aversion characteristics of banks. According to Shin and Kim (2014), these risk aversion characteristics of most banks may lead to a preference to finance better and less risky businesses. Consequently, risk-averse banks end up excluding women and ethnic minorities in the UK, who are perceived as high-risk clients. Ethnic minority black business owners have the greatest challenge raising external funds. Hence, women and ethnic minority groups end up using bootstrapping as the only strategy to finance their innovative small businesses.

The lack of collateral is another major challenge facing small innovative businesses in the UK. Collaterals act as a shield for lenders against potential losses emerging from default by clients. Mason and Harrison (2004) posit that the most common reason why banks deny small innovative businesses access to finance is the lack of collateral. The greatest number of rejected financial proposals of small businesses is due to the lack of collateral. Consequently, lenders end up lending businesses with the best collateral rather than businesses with high growth potential. Due to the current unavailability of debt finance, small innovative businesses are now seeking equity finance from venture capitalists and business angels. Nevertheless, venture capitalists and business angels do not fill the existing equity gap since they tend to favour businesses with high growth potential because they promise the highest returns. Since most small innovative businesses are perceived as low return ventures, a significant number of small innovative businesses will still struggle to access equity finance.

Changes in financing innovative small businesses in the UK

The existing financing challenges facing small innovative businesses have forced them to shift from the traditional debt financing strategy to crowdsourcing and the use of government subsidies. Innovative small firms are unlikely to qualify for business credit in most cases. In return, entrepreneurs seek an alternative source of financing, which is commensurate with their business ideas. Lenders charge interest rates based on perceived default risk and potential market failure. Since innovative small firms are perceived to have high chances of market failure, the rate of interest charged is higher than that of large companies. There has been a significant change in financing small businesses due to factors such as advancement in technology and government subsidies to empower young entrepreneurs. Advancement in technology has enabled innovative firms to raise start-up capital through crowdsourcing. These changes have enabled small firms to raise start-up capital at low-interest rates. Moreover, small firms can venture into risky businesses without having to undergo strict scrutiny in bank and venture capital lending.

Crowd financing

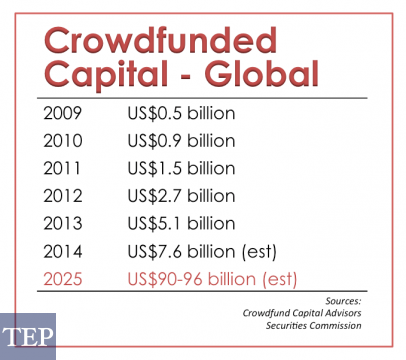

The UK financial system has experienced dramatic changes in the way small innovative businesses can raise start-up capital. Technology advancements have made it even easier to reach more people and businesses at almost zero cost. Crowdsourcing is facilitated by online platforms that allow project financing by small contributions from a large number of people. This financing method has been growing rapidly in the last 5 years. In the UK, crowd fundraising is facilitated through the Crowdsourcing.org website, which focuses on financing small innovative businesses. According to Belleflamme, Lambert, and Schwienbache (2013), in 2011, 453 crowdsourcing financing platforms existed and were responsible for raising more than $1.5 billion to finance small business projects. Crowdsource allows small innovative businesses to borrow start-up loans at an affordable rate. In fact, FundingCircle, which is a London-based crowd fund provider, has offered significant business loans to support innovative small firms. Crowdsourcing platforms have raised more than £35 million to finance small businesses (Vasilescu 2014). This model allows large groups of people to own a stake in young businesses with the ultimate goal of reaping high returns if the project becomes successful. Crowdsourcing plays an intrinsic motivation role to support young businesses, thus enabling entrepreneurs to realise their goals. Crowdsourcing is gaining popularity across the globe as shown below

This motivation to support innovative small businesses will potentially play a significant role in encouraging investors to invest. The equity crowd financing model will potentially allow young innovative business entrepreneurs to invest in risky investments that traditional providers cannot finance. This model will benefit mostly those people intending to invest in the so-called equity gap investment where other financiers consider it as high-risk ventures.

Bank lending

Bank lending is the most common way of financing young innovative businesses. External finance is extremely important in funding start-up innovative businesses. Banks play a critical role in the UK by offering start-up capital for small businesses. Although external finances like debt capital are considered expensive, bank contribution toward the sustainable UK cannot be ignored. The UK government has made significant steps to ensure that many small innovative businesses gain easy access to finance by establishing the British Business Bank. The bank has supported more than 38,000 young entrepreneurs by lending them start-up capital to avoid market failure. However, the banking sector in the UK prefers to finance less risky businesses. In summary, banks are the most common source of external finances for small innovative businesses.

Implication of Government initiative to finance small innovative businesses in the UK

The UK government has played a significant role in financing small businesses. This trend stems from the fundamental contribution of small businesses in creating a sustainable economy through job creation. The UK government invested £400 million in the British innovation scheme. The main purpose was to enable small innovative businesses to gain easy access to cheap start-up capital. The program intends to nurture the British entrepreneurial talent, which is vital to the economy by minimising market failure of small firms. For instance, Growth Accelerator is a government-financed program intended to finance more than 26,000 small businesses (Dai 2011). Easy means of financing start-up businesses are likely to improve the living standards of many British citizens by offering job opportunities. In fact, research work conducted between 2009 and 2013 highlighted that more than half of the new employment growth is generated by small to medium-size businesses (Vasilescu 2014). Around 11,000 businesses were responsible for generating 70,000 new jobs and an estimated £2 billion in economic growth (Vasilescu 2014). In conclusion, government subsidies will improve the UK economic growth and facilitate the creation of new jobs.

Conclusion

This study has explored different strategies that can be used by an innovative small firm such as to finance their business. Although venture capital is the most preferred option for many businesses, sometimes this option might reject financing small businesses. This assertion is based on the view that venture capitalists use strict criteria, which many start-up firms cannot meet. This study establishes that many start-ups thrive in the business niche that changes rapidly and industries that are deterred by changes in uncertainty in the long term. However, investors prefer businesses that have a well-defined market with sound prospects of expanding in future to avoid market failure. In addition, investors have to be convinced by the growth projections of the start-ups before investing their money. The objective of any investor is to make returns from any investment, and thus they will tend to avoid start-ups because such businesses have a long way to go before making substantial returns. Bootstrapping requires a different mind set-up and not just relying on basic principles and practice that will not help entrepreneurs.

Referencing List

Alperovych, Y & Hübner, G 2013, ‘Incremental impact of venture capital financing’, Small Business Economics, vol.41, no.3, pp. 651-666.

Angilella, S & Mazzù, S 2015, ‘The financing of innovative SMEs: A multicriteria credit rating model’, European Journal Of Operational Research, vol.244, no.2, pp. 540-554.

Balázs, F 2014, ‘Government interventions in the venture capital market – how Jeremie affects the Hungarian venture capital market’, Annals of the University of Oradea, vol.23, no.1, pp. 883-892.

Belleflamme, P, Lambert, T & Schwienbacher, A 2013, ‘Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd’, Journal of Business Venturing, vol. 6, pp. 1-25.

Bhide, A 1992, ‘Bootstrap Finance: The Art of Start-ups’, Harvard Business Review, Web.

Chemmanur, T & Fulghieri, P 2014, ‘Entrepreneurial Finance and Innovation: An Introduction and Agenda for Future Research’, Review of Financial Studies, vol.27, no.1, pp. 1-19.

Cressy, R 2009, ‘Venture Capital’ in M Casson, B Yeung, A Basu & N Wadeson (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurship, Oxford University Press, pp. 353-386.

Crowdfund Capital Advisors: Crowdfund investing resources 2015, Web.

Dahlman, C & Aubert, J 2010, UK and the Knowledge Economy Seizing the 21st Century, World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Dai, M 2011, Innovative computing and information international conference, ICCIC 2011, Wuhan, China, September 17-18, 2011, proceedings, Springer, Berlin.

Golić, Z 2014, ‘Advantages of crowdfunding as an alternative source of financing of small and medium-sized enterprises’, Proceedings of the Faculty of Economics in East Sarajevo, vol.8, pp. 39-48.

Mason, C & Harrison, T 2004, Does investing in technology-based firms involve higher risk? An exploratory study of the performance of technology and non-technology investments by business angels’, Venture Capital, vol.6, no.4, pp. 312-331.

Nienhuis, J, Cortet, M & Lycklama, D 2013, ‘Real-time financing: Extending e-invoicing to real-time SME financing’, Journal Of Payments Strategy & Systems, vol.7, no.3, pp. 232-245.

Ozioma-Eleodinmuo, P 2015, ‘Analysis of Entrepreneurship Policy for Small and Medium Scale Enterprise in Aba, Abia State Nigeria’, Journal of Economic Development, Management, IT, Finance and Marketing, vol.7, no.1, pp.47-60.

Politis, D 2008, ‘Business Angels and value added: what do we know and where do we go?’ Venture Capital, vol.10, no.2, pp.127-147.

Ramadani, V 2009, ‘Business angel: who they really are’, Strategic Change, vol.18, no. 7/8, pp. 249- 258.

Revest, V & Sapio, A 2012, ‘Financing technology-based small firms in Europe: what do we know’, Small Business Economics, vol.39, no.1, pp. 179-205.

Rossiello, A & Parris, S 2009, ‘The patterns of venture capital investment in the UK bio-healthcare sector: the role of proximity, cumulative learning and specialisation’, Venture Capital, vol.11, no.3, pp.185-211.

Shin, M & Kim, S 2014, ‘The Effects of Private Investments in Public Equity on R&D Investment in Small and Medium-Size Enterprises’, Emerging Markets Finance & Trade, vol. 50, no.6, pp. 43-59.

Wray, F 2012,’ Rethinking the venture capital industry: relational geographies and impacts of venture capitalists in two UK regions’, Journal of Economic Geography, vol. 12, no.1, pp. 297-320.

Vasilescu, L 2014,’Accessing finance for innovative EU SMEs – key drivers and challenges’, Economic Review: Journal Of Economics & Business, vol.12, no.2, pp. 35-47.

Zinecker, M & Bolf, D 2015, ‘Venture capitalists’ investment selection criteria in CEE countries and Russia’, Business: Theory & Practice, vol.16, no.1, pp. 94-103.