Introduction

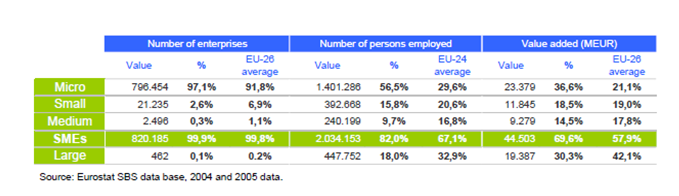

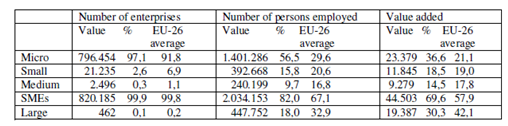

According to official figures, there were 742, 600 SMEs in Greece. They had a combined 2,512,493 employees, representing 85% of total employment, which was well above the EU average (OECD, 2002). This means that there are 73 SMEs per 1000 inhabitants in Greece (OECD, 2002). It is also worth noting that more than 97% of all the business enterprises in Greece are micro-companies (OECD, 2002). The SMEs make a very significant contribution to the Greek economy, representing a very large share of total employment and value-added. The SME sector is crucial to any country’s competitive development.

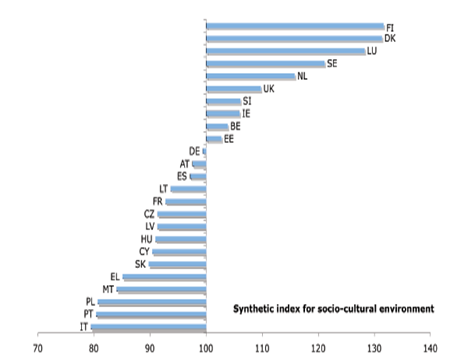

This paper is a general study of the Greek SME environment. It looks at the factors that influence the organization, performance, success, and failure of the Greek SMEs. The factors studied here are socio-cultural, technological, and economic. The paper also looks at how the Greek SMEs are adopting the use of ICT to drive growth in the modern business environment. The paper concludes by looking at how the Greek SMEs can foster growth in the future, especially in the wake of European Integration. The table below shows the characteristics of the SME sector in Greece (Eurostat, 2012)

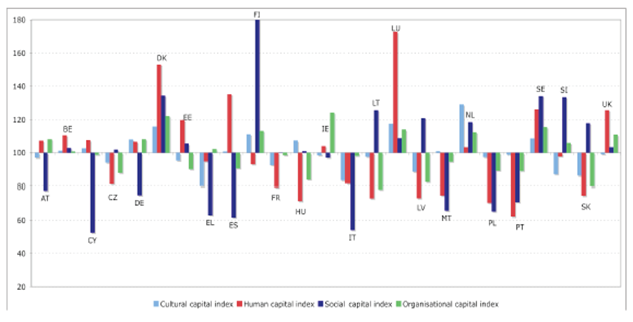

Socio-Cultural Factors

Socio-cultural factors are usually used to characterize a geographically defined community rather than a business sector or enterprise. Nevertheless, the environment in which the Greek SMEs operate exposes them to influence from many of these factors. With Greece being part of an integrated European market, there are bound to be several external influences on the operations and performance of its SMEs. For example, there are large multinational corporations that usually ‘impose’ their management ‘culture’ on their operating divisions in foreign countries (Roger, 1999). They also impose their standards and practices on suppliers, causing the SMEs to sometimes diverge from their ‘home’ cultural practices as far as business is concerned.

When one considers the demand aspect, it is clear that not all products share similar inherent characteristics, and they also happen to be sensitive to consumer demand (Levy & Powell, 2005). A well-organized marketing campaign can change the perceptions of a product in any society. In the same way, interest groups, lobbies, and changing social values can also promote or undermine a certain product. These societal factors, together with changes in the balance of market power, can heavily influence the performance of certain types of businesses more than others can. There are various dimensions that can be used to study the socio-cultural characteristics of any business entity. For this paper, we will look at four dimensions that are used to describe the socio-cultural characteristics of Greek SMEs. These are:

- Organizational capital and entrepreneurship

- Human capital

- Social capital

- Cultural capital and consumer behavior

Under each of these dimensions are specific elements that are very influential to the overall performance of the SME.

Organizational capital has a direct impact on the performance of a company. An organization’s resources do not just refer to cash flow or specialized personnel, but also the company’s management structure and style, company culture, routines, and morality. There are several aspects that are indicative of the organizational capital and the entrepreneurship dimensions. These include the relationship between employers and employees, employees’ attitudes towards work, the company attitude towards risk, and the organizational rigidities in place (Ladi, 2005). In Greek SMEs, the empowerment of employees by management is very low, and there appears to be a confrontational relationship between the two parties. However, many people are particularly open to the idea of starting a new business regardless of a high risk of failure.

Human capital refers to the skills, knowledge, and attributes that a company’s employees have acquired through education, training, and work experience (Gregersen & Johnson, 1997, p. 485). Businesses usually accumulate knowledge by harnessing it from formal institutions through research, education, and training. They also promote learning through interactions within the employees, and with suppliers, consumers, and other business partners.

In Greece, the proportion of a higher educated workforce is average as compared to other EU countries. The workforce is also a bit rigid due to the little diversity of nationalities providing skilled labor. When it comes to human capital, Greece can be grouped as being n the middle road when compared to other EU states. These characteristics are reflected across SMEs in all sectors.

Social capital is defined as “networks together with shared norms, values, and understanding that facilitate cooperation within or among groups” (OECD, 1997). The inference here is that social contacts and networks influence the productivity of individual employees and the company in general. Social capital varies from one sector to another and is heavily dependent on cooperative behavior. The Greek SME environment can be classified as a closed network. There is a low level of trust between the SMEs and their customers, competitors, and suppliers. There is also a high level of corruption and little cooperation with other sectors.

Cultural capital refers to the inherent and acquired properties of a person’s behavior over time. These properties are acquired through interactions with the family and society, and they shape that person’s character and way of thinking. In essence, the cultural background shared by a group of people will influence their attitudes and habits, including consumer behavior. The cultural capital and consumer behavior will influence the performance of SMEs mainly in terms of markets (Roger, 1999).

When it comes to cultural capital and consumer behavior in driving the performance of SMEs, Greece performs poorly in comparison to other EU countries. In this regard, Greeks are considered conscious conservatives. They are not open towards other cultures, or the introduction of new risky technologies into the business arena. They are also less committed to environmental concerns, yet these have become very important in the current business environment.

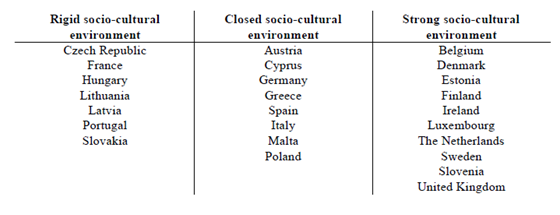

The overall interaction of all the above factors gives an indication of the general socio-cultural environment that Greek SMEs are operating in and how it can impact n their operations and performances. When compared with other EU countries, it is clear that the socio-cultural environment in Greece is relatively poor for SMEs to thrive in. Greece would be classified as having a closed socio-cultural environment.

Technological Factors

SMEs in the manufacturing sector needs technological innovation if they are to have industrial competitiveness and contribute to national development (Cohen & Levinthal, 1989, p. 580). The technological factors that influence innovation in business organizations can be classified into two broad categories:

- Tactical influences – These include drawing knowledge from external networks, making use of in-house technological and market competencies, and having appropriate mechanisms for the implementation of the organizational structure.

- Strategic influences – Refer to conditions that are necessary for there to be sustainable innovation. They include a corporate strategy that values innovation, top management commitment, a positive attitude towards risk and innovation, and environmental factors that favor innovation.

Innovation involves new products or manufacturing processes that the company can come up with on its own or acquire from external sources (Cohen & Levinthal, 1989, p. 589). The most common forms of innovation amongst Greek SMEs involve incremental improvements on what they already have. The top management has a crucial role in driving innovation in the company. According to the neoclassical economic theory, some of these factors that spur innovation include specific local demands, a highly competitive business environment, availability of skilled labor, and good communication networks.

There are also ‘national innovation systems, for example, investment in technology-based learning systems in educational institutions. The neo-institutional theorists emphasize the importance of the country’s institutional framework as playing a big role in contributing to technological advancement.

The development of the Greek economy since the Second World War has been largely dependent on technologies imported from other countries. The Greek productive system has relied on foreign direct investment, licensing, and capital goods imports. Research and development in local industries are limited, and the research institutions that are there are not sufficient to create meaningful research that would attract the interest of industries. The administrative factors hindering technological innovation include poor legislation, outdated educational and training systems, and lack of intellectual property rights (Kogut & Zander, 1996, p. 194).

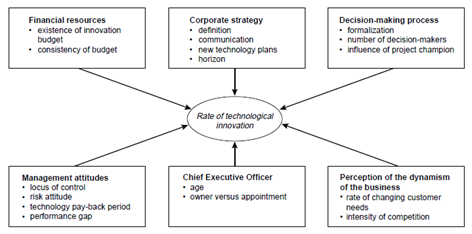

High-income taxes have also been shown to discourage wealth accumulation and the growth of a big business. Greece is a newly industrialized economy with an industrial structure dominated by SMEs. Most of these SMEs are run by the owners and a few top managers. It is these owners and the small management team that come up with most of the new innovative products, with the R&D and marketing departments playing a less significant role. The table below shows a portfolio model of strategic influences of innovation (Eurostat, 2012).

The above model does not exhaust all the factors that influence innovation in Greek SMEs but highlights some of the most important ones. First, financial resources are very important in driving innovation, and most SMEs cannot undertake major innovations because they are too costly. Nevertheless, SMEs need to budget for innovation, and it is important that this funding is consistent and stable (David & Foray, 1995).

Corporate planning that includes innovation as part of the business strategy is also essential. This strategy should be communicated to all the employees of the firm. Studies have shown that companies that directly include technological projects into their business strategy are usually the most innovative and subsequently more competitive (Cruz-Cunha, 2010). The plans for innovation projects should be long-term if they are to yield better outcomes. The decision-making process in regards to innovation ought to be formal, and every employee should have a clearly defined role. In the Greek business environment, firms that had younger CEOs and those that were owned by their CEOs have the highest rates of innovation.

Studies have shown that in the Greek SMEs environment, the most important influences of innovation are the ones that are not country-specific or institution-based (Cruz-Cunha, 2010). The most innovative SMEs are those that have overcome the traditional obstacles associated with national institutions and have incorporated novel attitudes and practices into their business. Owners and managers who have noticed there is a stiff competition or changing customer needs are usually most likely to take innovation seriously. If the SMEs want to thrive, the top management has to incorporate technology into their business strategy and have a positive attitude towards risk.

Economic Factors

Greek SMEs need to have financial resources and establish cooperative relationships with each other if they are to remain viable and competitive. Since SMEs form the backbone of the Greek economy, their financial performance is crucial to the country and investors as well. Integration into the EU and globalization have opened up the Greek market and brought in strong external competition especially in the manufacturing sector. In order for the Greek SMEs to survive and be competitive, they need to be financially stable. Based on the economic theory, SMEs usually face problems of high production costs and low productivity due to small-scale production (Becker, 2004, p. 650).

Other problems include high costs of supply and shorter supply terms. In the wake of all these problems, they are forced to give their customers longer credit terms in order to promote their sales. The end result is that most Greek SMEs need a lot of working capital financing yet have low profitability. Most SMEs avoid long-term debts and instead go for short-term financing. Most of the Greek SMEs are small in size due to their reliance on the domestic market and the tendency to self-employment amongst other factors.

Sources of capital for Greek SMEs- The ability of a Greek SME to have access to capital is largely determined by its development phases, which will be used by the lending institutions to evaluate its creditworthiness. In the early phases of development, the SMEs rely mainly on the financial resources of the owners and their families. They may sometimes get assistance funds or venture capital. As the SME grows through the development phases, it is financed from accumulated financial surpluses and external capital. At the maturity stage, the firms have easier access to external capital especially in the form of bank loans.

As the internally accumulated finances of the SME become insufficient, external capital becomes the main source of funding for the firm’s investment projects (Ladi, 2005). Therefore, if the external capital is unavailable or insufficient, it will hinder the growth of the SME. SMEs mostly get their external capital from the so-called non-banking sources of finance. These include franchising, factoring, leases, trade credit, and loans from the non-banking sector (citation).

For the Greek SMEs, there is also funding from the government and EU assistance programs. Nevertheless, commercial banks remain the best source of finance for SMEs, and if the SME sector is to flourish, it must have access to bank credit. Getting credit from banks also comes with other secondary advantages. The bank will perform a detailed evaluation of the project to determine its feasibility, and provide professional guidance on the same.

Studies have shown there is little cooperation between the Greek SMEs and the banks. There are gaps in the financing of the SMEs right from the start-up phase up to the later phases (Geels, 2004, p. 911). This is highly unusual since the SMEs, by their nature, should be very attractive clients for the banks. There are several reasons for this unusual scenario. A good number of managers (over 40%) feel that the banks do not offer them products and services that suit them (Geels, 2004, p. 918). As a result, there is a low demand for banking services by SMEs. Only about a quarter of the SMEs turn to the banks first in case they need financial assistance or advice.

Other reasons for the poor relationship include high interests charged on bank loans, a requirement of collateral by the banks, and lengthy and complicated processes involved in obtaining the bank loans. These prohibitions are mainly felt by the smallest firms and start-ups. There are also some valid reasons on the banks’ side as to why they would be unwilling to lend freely to the SMEs. First, the inability of the SMEs to accumulate significant financial surpluses means that there is little guarantee that they will return the invested capital.

The high costs of operation, low profitability, and low level of managerial skills in the SMEs are also reasons for the banks to be extra cautious. Some banks feel that the SMEs are not well prepared to gain from the banking services. Another emerging reason as to why SMEs do not like banking services is that they feel the banks are not flexible enough whenever the SMEs are facing liquidity problems. The banks are very rigid when it comes to debt restructuring.

Most of the Greek SMEs do not like seeking external sources of capital. They mostly rely on the financial resources of the owners and retained profits to finance business activities. They only take loans to help maintain liquidity and not for investment projects. Studies have shown that young SMEs are more likely to seek external capital than the well-established ones that have been operating for many years. The SMEs that have had bad experiences with banks are highly unlikely to seek banking services again. In general, the Greek SMEs do not regard cooperation with banks as an integral aspect of their business strategy, and only seek the banks’ assistance in critical situations.

The financial problems of the Greek SMEs, especially in the manufacturing sector, have been compounded by a liberalized financial system, which makes borrowing more competitive. The fiscal constraints associated with the Greek economic environment also contribute to limited expansion opportunities for SMEs. It has also been discovered that banks also avoid providing loans to particular types of SMEs, including the highly innovative ones and the start-ups that do not happen to have sufficient collateral, or whose business activities are associated with high risks.

Use of ICT

The current business environment is characterized by the globalization of markets and intense competition. SMEs have to find ways of modernizing their operations in order to survive and prosper. Many SMEs now use computers for various functions like budgeting, inventory, and payroll among other uses. However, the use of ICT goes beyond these common functions, and ICT is now the main force driving change in the business environment. Firms are now able to use information systems to link various internal departments and to link to their customers, suppliers, and business partners (Al-Qirim, 2004).

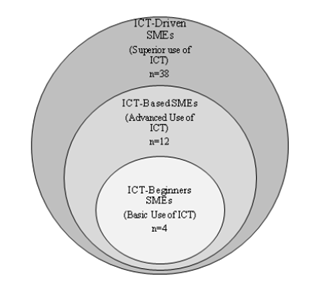

Many Greek SMEs have realized the important role that ICT can play in their growth and overall performance. There are different types of business software that help in the management of information within the business so that processes become more efficient and the business performs better. Even within the firm, the use of ICT makes the management of resources more efficient. The use of ICT not only improves the delivery of services but also helps in cutting costs in the process. A study conducted on the use of ICT by Greek SMEs categorized them into three distinct levels (citation):

- Level 1: ICT beginners/basic use of ICT by SMEs- These SMEs use ICT for basic processes like transactions and communications. They still manage their main business processes using the ‘traditional methods, and they regard ICT as a separate independent part of a business organization. Usage revolves around the internet, email, basic website, and local area networks.

- Level 2: ICT-based SMEs/Advanced use of ICT- These SMEs use ICT for specialized business activities like monitoring transactions, programming operations, auditing, and decision-making. They use advanced analytical models on their data to come up with functional frameworks that guide the operations of the business. They conduct business transactions electronically and transmit information across geographical borders easily. For these SMEs, ICT is a necessary part of the business, and their main business processes are based on it. The applications include management information systems, decision-support systems, e-commerce activities, and wide area networks.

- Level 3: ICT-driven SMEs/ Superior use of ICT: These SMEs have fully integrated ICT into their business set-ups. They use ICT for various advanced functions like long-term planning, commercial transactions, the digital exchange of information, and the integration of information and business processes. The use of ICT is at the core of all their business processes. Some of the ICT applications that they use include enterprise systems (ERP II, XRP, EAI), executive support systems (ESS), e-business activities, and virtual private networks. The graph below shows the levels of adoption of ICT.

From the above-mentioned study, it emerged that micro-firms were lagging behind in the adoption of ICT. This is because, in general, micro-firms are less flexible and lack the funds and experience to adopt the use of ICT. The various levels of ICT usage by SMEs have led to the emergence of new organizational forms of SMEs, and ICT is becoming the driving force behind their operations, both internally and externally. The numerous potential applications of ICT are now the basis of the organizational architecture of many SMEs (Al-Qirim, 2004). The use of ICT requires significant investment on the part of SMEs but once operational, the improved efficiency will bring in more returns for the business.

Future Growth

European Integration has brought in great opportunities and new challenges for Greek SMEs, and they have to find ways of adapting to survive the increased competition from outside and to take advantage of the new opportunities to grow and prosper. European Integration presents the Greek SMEs with an opportunity for rapid sales growth, which is a standard measure of competitiveness and dynamism in businesses.

The success of SMEs can be measured through the increases in turnover, revenue, or the number of employees (Cowan, David & Foray, 2000, p. 244). There are five general stages of SME growth; start-up, survival, growth, take-off, and maturity. The third and fourth stages are the most critical for businesses with big ambitions. In the third stage, the business has grown into a good size and is profitable as it enjoys good product penetration (Schröter, 2008).

The fourth stage determines whether it will develop into a big business or not. For the Greek SMEs, the most important determinant of successful growth is the attitude of the owner-manager. Many SME owner-managers opt not to grow the business because of several fears like going into debt or losing control of the business. They are also reluctant to hand over the management of the business to professionals who would oversee the growth (Ampelas & Hick-Clark, 2001).

Other factors that hinder growth are lack of finances and the technical know-how to facilitate the process of growth (Ampelas & Hick-Clark, 2001). Greek SMEs can partly solve the issue of lack of finances for growth by forming strategic partnerships with each other or with larger firms. They need to develop networks that will boost market penetration and economies of scale (Fontana, Geuna & Matt, 2006, p. 317).

This is one area that the Greek SMEs have been reluctant in exploring yet it has many potential benefits. The growth of a business also comes with low liquidity and high gearing, and this can lead to financial problems. This can be avoided through effective financial control so that the SME’s economic resources are used efficiently. Studies have revealed that the positive contributors to the growth of Greek SMEs include the profitability of total assets, long-term debt reliance, and employee productivity, while the negative contributors were liquidity, credit policy, and fixed asset turnover. Most of these growth-determining factors are largely under the command of the owner-manager of the SME so he stands to play the biggest role in the growth of his firm (Laursen & Foss, 2003, p. 258).

The government can also play a significant role in helping Greek SMEs achieve faster growth through various policy measures like providing low-cost financing and incentives for new investments, more so in new technologies. The government can also help the Greek SMEs form partnerships with foreign firms so that the SMEs can get to export their products by acting as suppliers to these big partners in other countries (Becker, 2004, p. 650).

Conclusion

It is widely acknowledged that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) play a leading role in the economic growth and development of any country. In Greece, the importance of SMEs is even more pronounced, as they constitute 99.8% of total firms and provide 91% of total employment. The Greek SMEs have not fully embraced technological innovation as a driver of growth and further development. The SMEs also lack adequate resources to invest in research and development to drive innovation. The Greek SME sector is also heavily influenced by socio-cultural factors. The Greek people have a higher tendency towards self-employment, which explains the presence of so many SMEs.

However, they are averse to risk-taking, and this has hindered the growth of the SMEs once they are established. Furthermore, there is little cooperation between the SMEs, and most owner-managers do not want to enter into strategic partnerships since they fear losing control of their enterprises. The Greek SMEs generally recognize the role of ICT in the current business environment, and most of them have incorporated ICT in their operations to various degrees. The future challenge is now how to survive and prosper in the highly competitive but highly lucrative European Common Market.

References

Al-Qirim, N. A. Y. (2004). Electronic commerce in small to medium-sized enterprises. Hershey, Pa: Idea.

Appeals, A., Hick-Clark, D., & the University of Manchester. (2001). Human resource management in Greek SMEs. Manchester: University of Manchester.

Becker, M. (2004). Organizational Routines: A Review of the Literature. Industrial and Corporate Change, 13(4), 643-678.

Cohen, W.M. and Levinthal D.A. (1989). Innovation and Learning: The two Faces of R&D. Economic Journal, 99(1), 569-596.

Cowan, R., David P.A., Foray D. (2000). The Explicit Economics of Knowledge: Codification and Tacitness. Industrial and Corporate Change, 9 (2), 211-253.

Cruz-Cunha, M. M. (2010). Enterprise information systems for business integration in SMEs: Technological, organizational, and social dimensions. Hershey, PA: Business Science Reference.

David, P.A. and Foray D. (1995). Accessing and Expanding the Science and Technology Knowledge Base. STI Review,16(2), 14-31.

Eurostat (2012). Structural Business Statistics: Database. Web.

Fontana, R., Geuna A. and Matt M. (2006). Factors Affecting University-Industry R&D Collaboration- The Importance of Screening and Signaling. Research Policy, 35 (1), 309-323.

Geels, F.W. (2004). From Sectoral Systems of Innovation to Socio-Technical Systems. Insights about Dynamics and Change from Sociology and Institutional Theory. Research Policy, 33 (1), 897–920.

Gregersen, B. and Johnson, B. (1997). Learning Economies, Innovation Systems, and European Integration. Regional Studies, 31(5), 479-490.

Kogut, B. and Zander, U. (1996). What Firms Do? Coordination, Identity, and Learning. Organization Science, 7(5) 190-196.

Ladi, S. (2005). Globalization, Policy Transfer and Policy Research Institutes. Northampton, Mass. [u.a.: Elgar.

Laursen, K. and Foss, N.J. (2003). New Human Resource Management Practices, Complementarities and the Impact on Innovation Performance. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 27(1), 243-263.

Levy, M., and Powell, P. (2005). Strategies for Growth in SMEs: The Role of Information and Information Systems. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (1997). Globalization and Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2002). OECD Small and Medium Enterprise Outlook. Paris: OECD Publications.

Roger, J. Y. (1999). Business and Work in the Information Society: New Technologies and Applications. Amsterdam [u.a.: IOS Press.

Schröter, H. G. (2008). The European Enterprise: Historical Investigation into a Future Species. Berlin [u.a.: Springer.