Introduction

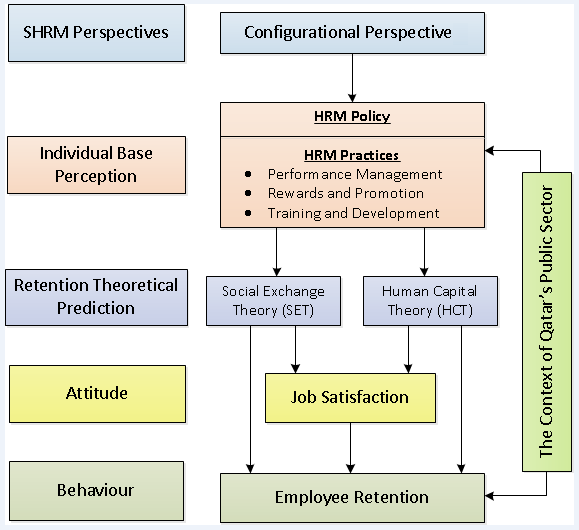

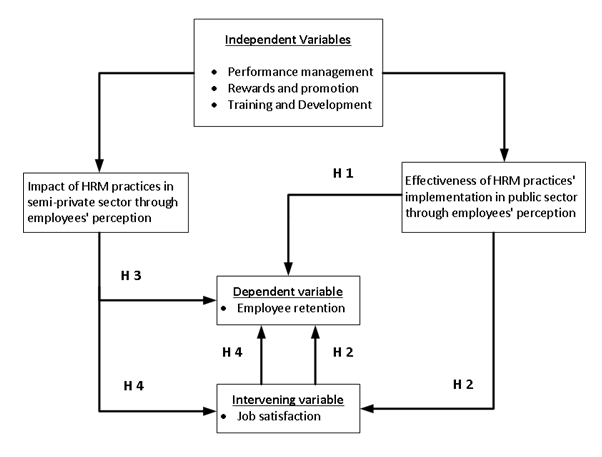

This chapter is structured to reflect the theoretical framework adopted for this research (Figure 1). The chapter provides the review of the previous research on the SHRM perspectives. The critical discussion of universalistic, contingency, configurational, and contextual perspectives provides the background for selecting the specific perspective for implementing HRM practices in organisations. In the context of Qatar, the practices mentioned in the 2009 HRM policy were planned to be implemented according to the principles of the configurational perspective (Arshad, Azhar & Khawaja 2014; Council of Ministers Secretariat General 2009; Raymond et al. 2010; Waiganjo & Awino 2012). The next section discusses HRM practices, such as performance management, rewards and promotion, and training and development, which are usually integrated into the strategy of organisations in order to address the employees’ needs (Abdullah, Ahsan & Alam 2009; Alusa & Kariuki 2015; Choi & Lee 2013; Kehoe & Wright 2013). The discussion of retention theories with the focus on the Human Capital Theory and Social Exchange Theory is important to explain the theoretical background for the study.

The next section provides the review of the studies on employees’ attitudes and behaviours in the organisational context. This section helps in understanding why retention in organisations should be discussed in the context of turnover intentions influenced by HRM practices and employees’ attitudes. Thus, the chapter presents the discussion of the relationship between HRM practices and employees’ perceptions, HRM practices and job satisfaction, as well as HRM practices and turnover intentions of workers that are associated with the retention in the organisation. Much attention is also paid to reviewing the researchers’ opinions regarding the realisation of HRM practices in the specific context of Qatar. The next section presents the gaps in the research that are planned to be covered in this study. One more section emphasises the process of formulating hypotheses for this study while referring to the prior research in the field, as well as assumptions associated with this investigation. The final section summarises the content of the chapter.

Strategic Human Resource Management and Perspectives

Strategic Human Resource Management or SHRM is an approach that addresses the wide range of management tasks. According to Choi and Lee (2013, p. 575), “Strategic HRM emphasises the relationship between HR activities and other organisational functions or strategies and examines the relationship between HR practices and organisational effectiveness at the facility and firm levels.” Therefore, SHRM approaches are closely connected with the organisational strategies and steps made toward achieving the corporate goals. The researchers note that these activities include the management of change, the improvement of performance, as well as the enhancement of the corporate culture (Collins & Clark 2003; Pourkiani, Salajeghe & Ranjbar 2011). In contrast to the traditional Human Resource Management or HRM that addresses only the problems of selection, recruitment, training and development, promotion, rewarding, and performance measurement, SHRM is used to modify and integrate the mentioned HRM practices in order to guarantee that the organisation will achieve the set strategic goals (Den Hartog et al. 2013; Ibrahim & Shah 2012; Martin-Alcazar, Romero-Fernandez & Sanchez-Gardey 2005). Traditionally, four approaches are used in the context of SHRM, and they can be applied by managers in their organisations. These approaches are known as the universalistic perspective, the contingent perspective, the configurational perspective, and the contextual perspective (Delery & Doty 1996; Martin-Alcazar et al. 2005). These models are different in terms of treatment that is used by managers in order to implement HRM practices in the organisation.

Universalistic Perspective

Proponents of applying the universalistic perspective in organisations note that it is effective to use only one, the ‘best practice’, in the company in order to achieve the higher results (Akhtar, Ding & Ge 2008; Loshali & Krishnan 2013). In this context, the ‘best practice’ means the universally taken approach that was proved to have positive outcomes. From this perspective, researchers assume that “some HRM practices are always better than others,” and “all organisations should adopt these practices to improve profitability” (Alusa & Kariuki 2015, p. 72; Delery & Doty 1996, p. 803). In their turn, Innes and Wiesner (2012, p. 33) claim that the universalistic approach is focused on “the notion that HR practices impact linearly on employee knowledge, skills, and abilities.” From this point, it is possible to observe a linear relationship between applied HRM practices and expected positive changes in the organisational performance after the implementation of the universalistic approach (Innes & Wiesner 2012). The supporters of this perspective state that the implementation of certain effective HRM practices can guarantee the increases in the company’s profitability and alterations in the employees’ performance (Hamid 2013; Takeuchi, Wakabayashi & Chen 2003, p. 449). Thus, Pfeffer offered sixteen best practices that could guarantee the positive impact on the performance in the organisation (Pfeffer 1998). Among the most important practices to influence the organisational performance, Pfeffer (1998) named compensation, teamwork, performance appraisal, training, and security of employees.

It is possible to determine several specific principles which are important to explain how the universalistic approach works in the context of the organisational development. According to Allani, Arcand, and Bayad (2003, p. 237), the key working principle is the universality of the best HRM practices that can affect the organisational performance and any changes in the management positively. Beh and Loo (2013, p. 158) agree that “for a firm to have effective human resource practices, it needs to copy and implement these universal best practices.” Managers are expected to implement those HRM practices which proved to be effective, and which can lead to positive outcomes. The other principle is the priority in choosing those HRM practices that can be discussed as strategic in order to achieve the corporate goals. The next principle is the autonomy of specific ‘best’ practices in terms of the approach to their implementation. Thus, the ‘best’ practices are usually implemented in organisations separately (Allani et al. 2003, p. 237). These principles are often followed in companies where the universalistic approach to SHRM is discussed as promising.

Contingency Perspective

Contingency means a kind of consistency that is related to using certain practices in different contexts in order to assist the organisation to achieve high results at different stages of the strategic development. According to Bakshi et al. (2014, p. 89), the contingency approach is known as the ‘best-fit’ one, and it suggests that the organisation’s human resource system and strategy “should be contingent on contextual factors and the effectiveness of HR practices depends on their fit with both external and internal context of the organization as there is no universal prescription that can be applied no matter this context.” In contrast to the universalistic approach, this model is based on understanding what practices can address the particular situation in the most effective manner.

The theorists who support the principles of the contingent perspective note that this perspective “goes beyond the simple, linear, causal relationships explored in universal theories,” and it is possible to discuss different relationships of factors and variables in the context of this approach (Colbert 2004, p. 344). In order to achieve the expected outcomes, managers need to determine the strategies to implement and choose HRM practices that can be applied to support the realisation of these strategies (Farr & Tran 2008). Lengnick-Hall et al. (2009) emphasized that the success depends on the appropriateness of the selected practices to address the concrete strategic goal. While applying the principles of the contingency perspective in the organisation, it is necessary to focus on the match between HRM practices and the specific stages that are typical of the organisation’s development (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2009; Schmidt et al. 2016). Lepak, Bartol, and Erhardt (2005) and Loshali and Krishnan (2013) note that different strategic and developmental stages require the utilisation of various HRM practices, and the manager’s task is to select the relevant practices to address the strategic goals effectively and receive adequate results.

The proponents of this approach claim that the variety of aspects can influence the successfulness of the strategy, and much attention should be paid to the impact of organisational and environmental factors (Wan-Jing & Huang 2005). Furthermore, the company’s life cycle is also an important feature to affect the choice of HRM practices that can be implemented in the organisation (Martin-Alcazar et al. 2005). In order to achieve the high results, it is significant to analyse the factors that can influence the company and its strategy and select the HRM practices that can be effectively integrated into the organisation in order to achieve innovativeness in operations, improve performance and productivity, and influence the employees’ and customers’ satisfaction (Akingbola 2013; Schmidt et al. 2016). From this point, the contingency perspective is selected by managers more often in comparison to the universalistic one because it allows developing the HRM system depending on the organisation’s needs.

Configurational Perspective

In contrast to the universalistic and contingency perspectives, the configurational model is characterised by the focus on the interaction between HRM practices that are implemented in a form of ‘bundles’ in order to achieve the certain strategic goal. According to Choi and Lee (2013, p. 575), the reason for concentrating on the “congruence among HR practices is that some combinations of HR practices, to the extent that they are consistent with one another, are more likely to have positive effects on organisational performance than the application of a single HR practice.” The proponents of this approach note that a combination of practices influences the employees’ perceptions, visions, and performance positively, and the outcomes are more obvious in comparison with the use of other approaches (Maryam & Sina 2013; Trehan & Setia 2014). The advantages of referring to bundles are identified more easily in contrast to practices that are implemented separately. Alusa and Kariuki (2015, p. 73) claim that such ‘bundles’ mean “configurations of HR practices that go hand in hand,” and they can contribute to the organisation’s competitive advantage. These configurations were discussed in detail by Delery and Doty (1996, p. 808), who referred to them as “unique patterns of factors, that are posited to be maximally effective” while improving the strategy and the performance in the organisation.

In their studies, Garcia-Carbonell, Martin-Alcazar, and Sanchez-Gardey (2014) and Uysal (2014) claimed that HRM practices can be viewed as a system with the determined horizontal fit, as well as the vertical fit. They are used to assess the internal effectiveness of HRM practices that should be selected to address both horizontal and vertical strategic directions (Innes & Wiesner 2012). As a result, the implemented bundle of HRM practices should be effective to address the tasks that need to be completed in these directions simultaneously. For this purpose, managers choose to “to develop interconnected and mutually reinforcing HRM policies and practices” (Arshad et al. 2014, p. 94). Waiganjo and Awino (2012, p. 83) support this idea stating that when HRM practices are applied in the organisation as a configuration of effective approaches, they can reinforce each other.

Theorists propose different combinations of practices that can be effective in order to achieve certain results. According to Den Hartog et al. (2013), these combinations are usually coherent and synergetic in their nature in order to expect positive outcomes. Therefore, the configurational approach is associated with the ideas of interaction, synergy, and integration used to achieve the set goals. Arshad et al. (2014, p. 94) note that ‘synergy’ should be discussed as a combination of practices that is “achievable only if HRM policies and practices perform in combination and better than the sum of their individual performances.” One more vision of the configurational model is formulated by Raymond et al. (2010, p. 124), who stated that a configuration is “the true essence of strategy to the extent that it results from the alignment (or “fit”) between the firm’s structure, activities and environment.” Another perspective is proposed by Martin-Alcazar et al. (2005, p. 637), who viewed the configuration as “a multidimensional set of elements that can be combined in different ways to obtain an infinite number of possible configurations.”

The researchers agree that the configurational model is based on the systemic interactions between different practices that are selected to address the same goal or support the certain strategy (Innes & Wiesner 2012; Stavrou & Brewster 2005). Therefore, when managers face a problem of improving the organisation’s performance, they choose to respond to the issue from several perspectives and focus on improving the working conditions for employees, increasing the rewards, improving the quality control system, and enhancing the performance management. This complex approach can guarantee the positive results since all the practices are implemented as a bundle and in a strategic manner (Payne 2006; Pourkiani et al. 2011; Wiklund & Sheperd 2005). From this point, Colbert (2004, p. 344) notes that the configurational perspective “follows a holistic principle of inquiry and is concerned with how patterns of multiple interdependent variables relate to a given dependent variable.” In this context, the configurational model is most advanced in comparison to the contingency perspective because of the application of the holistic approach.

Contextual Perspective

The contextual perspective as one of the SHRM models is referred to more rarely than other three approaches. However, there are researchers who claim that the implementation of HRM practices in organisations can depend on the broad contextual perspective. According to Martin-Alcazar et al. (2005, p. 637), the contextual approach “introduces a descriptive and global explanation through a broader model, applicable to different environments encompassing the particularities of all geographical and industrial contexts.” According to this model, specific contexts in which the organisation develops can influence it significantly because of a range of external factors associated with the business and economic development in the country that should be taken into account while preparing the strategy for the organisation and selecting HRM practices to implement in the firm.

Following the discussion of the model by Martin-Alcazar et al. (2005, p. 638), it is important to note that “while the rest of the perspectives, at best, considered the context as a contingency variable, this approach proposes an explanation that exceeds the organisational level and integrates the function in a macro-social framework with which it interacts.” This macro-social level is significant to influence the implementation of HRM practices in organisations because differences in the social and economic frameworks explain the differences in the effectiveness of this or that practice. As a result, the analysis of the appropriate HRM practices proposed in the context of the certain strategy is shifted to “a wider network of stakeholders” and to “social, institutional and political forces” (Innes & Wiesner 2012, p. 33). The context can influence each aspect of the firm’s progress, and such factors as the culture, economy, society, and politics affect the successfulness of certain HRM practices in different countries.

In their research, Al-Husan, Brennan, and James (2009) also focus on the cultural factors, and they discuss them as influential during the process of implementing practices in the organization. Innes and Wiesner (2012) conducted their study referring to this SHRM model, and they note that the contextual approach is important to explain how external factors can have the significant effect on the organisational development. This impact can be even higher than the effect of internal factors on the organisational performance.

Reasons to Refer to the Configurational Perspective

The recent research on perspectives of SHRM indicates debates regarding the appropriateness of referring to this or that approach. While responding to the debates regarding the appropriateness of universalistic, contingency, and configurational perspectives in different contexts, Arshad et al. (2014, p. 98) state that “no researcher is however, clear about the dominance of any of these three” models used as SHRM approaches. The implementation of Qatar’s 2009 HRM policy demonstrated how it is possible to adopt HRM practices presented as bundles in public sector organisations (Council of Ministers Secretariat General 2009). While referring to the configurational perspective, researchers and policy-makers also predicted the contribution to decreasing turnover intentions of employees working in the public sector (Williams, Bhanugopan & Fish 2011). It is important to note that in Qatar, the HRM policy was implemented according to the configurational perspective of SHRM since proposed alterations in performance management, rewards and promotion, as well as training and development were expected to be adopted simultaneously, as the part of the HRM system (Council of Ministers Secretariat General 2009). From this point, it is necessary to explain the relevance of the selected approach to the context of Qatar.

The scholarly literature presents different approaches to comparing and analysing perspectives of SHRM. According to Bakshi et al. (2014), the contingency perspective is more appropriate in organisations than the universalistic one because managers need to choose practices that are fitting certain contexts and stages of development. The reference to only ‘best’ practices means using only single or separate effective practices in order to change the situation in organisations during the concrete period of time (Ibrahim & Shah 2012; Subramony 2009). The universalistic approach often does not provide the long-term effects.

The opponents of following the universalistic perspective state that this approach ignores the impact of a range of factors on human resources that can affect the quality of their work (Onyemah, Rouzies & Panagopoulos 2010). Colbert (2004, p. 344) pays attention to the fact that the work “in the universalistic perspective is largely unconcerned with interaction effects among organisational variables and implicitly assumes that the effects of HR variables are additive.” In addition, Martin-Alcazar et al. (2005, p. 634) state that the followers of the universalistic approach usually do not “study either the synergic interdependence or the integration of practices.” As a result, the strategic approach to choosing HRM practices can be limited in cases when managers choose to refer to the universalistic approach.

On the contrary, the contingency perspective allows achieving the match between certain HRM practices and stages of the organisation’s development (Sanders, Dorenbosch & De Reuver 2008; Wan-Jing & Huang 2005). On the one hand, the contingency perspective could be used in the context of Qatar because fitting practices are applied in many organisations. On the other hand, the practices proposed according to the HRM policy were expected to be implemented in all public sector organisations of Qatar. The support for the use of bundles of practices instead of fitting practices is provided by Takeuchi et al. (2003) who noted that separate fitting practices are not as efficient as bundles of practices.

When managers choose to focus on sets of HRM practices, there are more positive effects on performance, job attitudes, and effectiveness of operations. In this context, the configurational approach is more holistic than the contingency and universalistic approaches (Colbert 2004). Still, it is also important to focus on the contextual approach as a broad perspective that explains different contexts within which organisations can be established (Martin-Alcazar et al. 2005). The contextual perspective seems to be relevant to explain the HRM policy and the implementation of HRM practices in Qatar. Nevertheless, it is important to note that Qatar’s policy-makers chose to maximise the outcomes of adopting the new HRM policy (Council of Ministers Secretariat General 2009). The symmetrical implementation of bundles of HRM practices in all organisations of the public sector could guarantee more positive effects in relation to the problem of retention (Den Hartog et al. 2013; Martin-Alcazar et al. 2005; Williams et al. 2011).

In addition, according to Allani et al. (2003, p. 238), the configurational model allows addressing four specific configurations, such as productivity, development, expansion, and repositioning. These configurations are important to be addressed in organisations in order to develop strategies effectively (Katou 2013; Scully et al. 2013). Thus, the realisation of the strategy in the organisation depends on the implementation of aligned HRM practices that address the horizontal and vertical fits in the company. In their research, Den Hartog et al. (2013) state that the adoption of only one HRM practice cannot contribute to improving the performance or perception of employees. A series of non-connected practices is also less effective than the implementation of a bundle of connected practices. It is typical of managers in the Middle Eastern countries to adopt HRM practices in the context of a certain strategy or a system (Iles, Almhedie & Baruch 2012; Scurry, Rodriguez & Bailouni 2013). From this point, the configurational perspective is more appropriate in comparison to the broad contextual perspective that does not explain particular details typical of not only different contexts but also industries and organisations (Dhiman & Mohanty 2010). Moreover, Martin-Alcazar et al. (2005) note that universalistic, contingency, and configurational perspectives are based on the same theoretical backgrounds, when the contextual perspective is based on theories other than Social Exchange Theory or Human Capital Theory. The analysis of the scholarly literature indicates that the configurational perspective of SHRM is selected by policy-makers of Qatar in order to address strategic goals of public sector organisations directly.

Individual Base Perception: Human Resource Management Policy and Practices

In their practice, managers use a variety of HRM tools and approaches in order to increase the employees’ quality of work, improve performance, contribute to their positive attitudes, and promote retention (Ansari 2011; Bambacas & Kulik 2013). If such HRM practices as recruitment and selection are associated with the issue of attracting talents to the organisation, the other practices, including performance management and appraisal, rewards and promotion, and training and development, work to influence the employees’ perceptions, visions, attitudes, and behaviours (Chew & Chan 2008; Collins & Clark 2003). These practices are also important to affect the employees’ vision of the company’s image, commitment, and dedication that add to their professional successes and the associated retention (Conway & Monks 2008). In this section, it is important to discuss such HRM practices as performance management, rewards and promotion, and training and development in detail and with references to reviewing the existing literature in the field.

Performance Management

The performance management is a HRM practice that is oriented to monitoring the employees’ performance, administering the productivity and progress, and appraising the successes. Shih and Chiang (2005) pay attention to the fact that the practice is based on the understanding and the constant communication between supervisors and employees that can guarantee that the performance is coordinated and evaluated on a regular basis. ALDamoe, Yazam, and Bin Ahmid (2011, p. 78) view the performance management and appraisal as the process of “evaluating directly the subordinate job specific performance priorities and expectations, communication, and assigned responsibilities.” In addition, managers are responsible for providing the “episodic and scheduled feedback that seeks to enhance teamwork and promote greater efficiencies and abilities” (ALDamoe et al. 2011, p. 78). According to Selden and Sowa (2015), the performance management is also oriented to increasing the employees’ potential and commitment to the organisation through the effective communication, support, and feedback. The appropriate performance management that is followed in the organisation as a HRM practice can also lead to increasing the productivity (Dhiman & Mohanty 2010). Therefore, this practice is usually integrated into the strategic management plan proposed by leaders. Tabiu and Nura (2013) found that the performance management is an important factor in order to influence the competitiveness of the firm. Donate, Pena, and Sanchez de Pablo (2016) also note that the effective performance management is perceived by employees as positive to affect their commitment and career development. Employees are inclined to discuss the performance appraisal as the part of performance management and point at the importance of the recognition, as well as provision of comments and feedbacks that are appropriate to stimulate the employees’ development.

Aladwan, Bhanugopan, and Fish (2014) found that there is a direct relationship between the adequate performance appraisal and management as a practice and the overall performance of employees who are inclined to demonstrate higher results when they are supportive by managers. In their turn, Edgar and Geare (2005) and Farr and Tran (2008) claim that managers usually decide regarding the promotion of employees referring to the results of the performance appraisal. Such assessment is important in order to determine the strong sides of an employee and his or her potential to be promoted in order to receive the higher position in the company. Gavino, Wayne, and Erdogan (2012) emphasize that the performance management and provided assessments are important for managers to guarantee that only the high-class specialists work in their organisation, and their talents can contribute to the company’s development. Referring to these data, it is possible to conclude that while utilising such HRM practices as performance management, employers can use the potential and skills of employees to their maximum.

Gheitani and Safari (2013) suggested that the developed performance management in organisations that addresses the organisations’ needs and weaknesses, refers to the expectations of employees and customers and serves for improving the overall effectiveness of management and operations is important in order to make the firm a leader in the market. Therefore, researchers are inclined to associate performance management with the changes in the company’s performance (Aladwan et al. 2014; Selden & Sowa 2015). Still, such authors as Dhiman and Mohanty (2010), Ibrahim and Shah (2012) and Karanja (2013) determine appraisal, assessments, and evaluations as the important elements of this practice and discuss how this approach can contribute to positive changes in employees’ attitudes and behaviours. The effective planning of employees’ work and the constant monitoring of successes and changes, as well as the application of strategies to cope with weaknesses in performance, can contribute to positive outcomes for the organisation. However, the effectiveness of this practice is also assessed with references to the employees’ perceptions that need to be taken into account. From this perspective, the researchers pay much attention to discussing the possible correlation between performance management practices and tools and changes in employees’ perceptions, visions, and behaviours.

Rewards and Promotion

Theorists and practitioners in the sphere of human resource management state that the compensation, rewards, and benefits are effective tools in order to stimulate employees to work better and feel commitment associated with the concrete organisation (Selden & Sowa 2015; Shih, Chiang & Hsu 2006). Thus, the developed HRM compensation practices can be used in order to attract the talents successfully. According to Conway and Monks (2008) and Karanja (2013), the proposition of the attractive rewards and compensation systems is one of the most actively used practices in organisations. The studies support the idea that the effectively developed system of rewards applied in the organisation is one of the key aspects to influence not only the employees’ choice of the position but also their productivity (Conway & Monks 2008; Karanja 2013; Kashyap & Rangnekar 2014). Kehoe and Wright (2013) found that the possibility to receive high salaries that reflects the work outcomes and efforts is attractive to employees who are often inclined to assess their successfulness as a professional with references to the wage they receive. Majumder (2012) also states that the overall organisational performance can be improved if managers propose the compensation and benefits plans that are regarded by employees as attractive, and they should also provide the feeling of the financial safety. Gheitani and Safari (2013, p. 98) continue the discussion of the problem while noting that “organizational pay systems are related to a number of issues such as individual output, retention and voluntary turnover strategy orientation, or organizational performance.” Thus, any efforts made by managers in order to improve the compensation policy can have effects on the employees’ vision of their safety or retention.

While discussing the available rewards, employees focus on the provision of material or financial rewards, as well as such benefits as leaves, assistance, and extra days off among other ones. The planning of different types of rewards is selected by managers as one of the critical HRM practices which aim is to address the employees’ needs, provide the comfortable conditions, motivate to improve the performance, and enhance the productivity (Conway & Monks 2008; Gheitani & Safari 2013; Karanja 2013). Kashyap and Rangnekar (2014) suggested that employees are inclined to perceive financial non-material benefits as important for them. There are cases when possibilities to receive the good pension, to support the work-and-life balance, and to have the insurance are valued by employees higher than financial rewards, and managers need to pay attention to this type of benefits while adopting this HRM practice (Marescaux, De Winne & Sels 2012). While balancing these benefits in compensation plans, managers are able to attract the talents and contribute to their retention. Many studies support the idea that wages and other types of rewards can influence the employees’ productivity and performance directly while affecting the persons’ satisfaction (Kehoe & Wright 2013; Mellahi et al. 2013; Nishii, Lepak, and Schneider 2008; Rahman et al. 2013). The risks for organisations to fail in retaining the employees are associated with the undeveloped compensation and promotion plans.

Dhiman and Mohanty (2010) note that employees also pay attention to the factors that influence the distribution of rewards in the organisation. It is important for employees to understand the criteria that can affect the decisions regarding the distribution of benefits or determination of the wage (Nishii et al. 2008; Rahman et al. 2013). Managers in developed organisations are inclined to connect the performance management and appraisal practices with the procedure of distributing rewards in order to ensure that the competency-based compensation is provided in their organisations (Ibrahim & Shah 2012; Karanja 2013). According to Gheitani and Safari (2013), this approach to determining the size of compensation and rewards is valued by employees who are motivated to improve their performance. Rasouli et al. (2013) established in their research that those employees who discuss the distribution of rewards as unfair in their organisations are more likely to find the job in companies-competitors. Therefore, the task of managers is to develop the effective policy according to which the distribution of rewards and benefits is realised in the organisation (Rahman et al. 2013; Rasouli et al. 2013). In public sector organisations, the principles of HRM practices are often based on guidelines presented in the HRM policy adopted for the concrete sector or industry (Antwi et al. 2016; Giauque, Anderfuhren-Biget & Varone 2013). The criteria regarding the planning of the compensation packages and systems of benefits should be followed directly, and aspects of these guidelines can influence the employees’ visions regarding the effectiveness of the rewards practice applied in the concrete organisation.

Promotion is another HRM practice that is actively used in management in order to accentuate the successes of employees as specialists in the concrete field; to guarantee that the higher positions in the organisation are taken by the high-quality and experienced professionals; and to contribute to realising the workers’ potential and their career development. Moreover, Gkorezis and Petridou (2012) state that employees often perceive the promotion opportunities as a kind of rewards for them. Aladwan et al. (2014) agree that employees are inclined to view the promotion in the organisation as a kind of recognition and support that can result in the increased commitment and improved performance. It is important for employees to understand that their efforts and talents are valued. In addition, the opportunity to be promoted can increase the employees’ initiative and engagement in the projects that can contribute to their career development. Those employees who are promoted in organizations regularly are characterized by the higher level of productivity because they usually plan the next promotion associated with their personal vision of the career development (Antwi et al. 2016; Nishii et al. 2008; Rahman et al. 2013). Therefore, the effectively formulated promotion strategy can affect the climate in the organization and employees’ activities and efforts.

Al-Husan et al. (2009) also claim that the opportunity to be promoted plays the key role for employees because it is an important psychological factor. If an employee knows that his or her efforts will be valued, the performance improves, as well as the motivation to achieve the success. Ibrahim and Shah (2012) state that many employees in public sector organisations use opportunities to be promoted, and they are interested in promotion practices followed in the institution because in the public sector, the benefits associated with higher positions are obvious, and the majority of advantages which are taken into account when employees choose between private and public sectors are base on the level of position or a status (Majumder 2012; Meyers & Woerkom 2014). As a result, HRM practices associated with the promotion in public organisations attract more attention of employees who plan to build careers in this sphere.

Training and Development

The modern competitive environment requires employees with advanced skills, and moreover, employees need to receive the training that addresses the trends in the industry in order to overcome challenges that are associated with the lack of qualification (Bhatti et al. 2013). According to Aladwan et al. (2014, p. 17), training and development “is the most significant indicator or subsystem of human resource development as it potentially enhances, increases and modifies the capabilities, skills and knowledge of employees and managers, enabling them to perform their job in more creative and effective ways.” From this perspective, training and development are HRM practices that are often used by managers in order to improve skills of their employees and contribute to their professional and self-development. In their research, Selden and Sowa (2015) state that the career development and the acquisition of new skills are the important factors to influence the employees’ motivation and the desire to participate in training and development programs.

There are many definitions of these practices applied in organisations. According to Chen (2014, p. 356), “training, if utilised effectively, may increase the job satisfaction and organisational commitment and employees tend to stay longer in the organisation.” Training and development programs are implemented as the part of HRM practices in many modern organisations because, according to ALDamoe, Yazam, and Bin Ahmid (2011, p. 78), “in today’s competitive environment driven by the knowledge economy, certain attributes and competencies of personnel are an integral component of organisations’ competitiveness.” Managers are interested in skilled and experienced workers; therefore, the training programs are significant to improve the employees’ knowledge and enhance their skills. From this perspective, if the programs supported these practices are selected appropriately, it is possible to expect significant improvements in employees’ abilities, skills, capacities, and the desire to enhance their knowledge.

Kesen (2016) found that managers usually choose effective training programs as a kind of the investment in the human capital in order to contribute to the talents’ development. Those organisations that pay more attention to training their employees are inclined to implement innovative technologies and strategies easily, and employees can regard these organisations as more attractive in comparison to the other firms (Chuang 2013). While implementing the training sessions and proposing development programs, managers expect the increases in the employees’ productivity, positive changes in the quality of the performed work, changes in the communication and cooperation between employees, and increases in the customers’ satisfaction associated with the high quality of the provided services. It is significant for workers to understand the training sessions and development programs as investments in their future of professionals in the concrete sphere (Rahman et al. 2013). In their turn, employees are inclined to assess the opportunities that are proposed by employers regarding their further training and development. Snape and Redman (2010) pay attention to the fact that employees are interested in participating in training sessions in order to develop competencies that can be utilised for the further career development. In many cases, employees choose the promotion in the organisation that provides many opportunities for the professional development and growth with the help of internal and external training programs (Saddam & Abu Mansor 2015; Sarker & Afroze 2014).

Sarker and Afroze (2014) state that the implementation of effective and rather expensive training programs can results not only in acquisition of specific skills by employees and their professional growth but also in the increased turnover rate because employees are constantly seeking organisations that can provide opportunities for their professional growth. Smeenk et al. (2006) are inclined to support the opposite opinion according to which, the training and development programs demonstrate that the company values its employees and contributes to their progress. Snape and Redman (2010) support the idea that if the training is relevant and planned effectively, employees can improve their knowledge and skills, as well as change their attitude to the organisation.

In their research, Tabiu and Nura (2013) found that employees’ motivation regarding the work and improvement of performance increases if they understand that managers are ready to spend resources for their development. In this context, much attention is paid to analysing how employers finance the training programs, whether they refer to internal or external resources, and how the completion of the program can influence the further promotion and salary. The appropriate reference to training and development as HRM practices should mean focusing not only on outcomes for the collective needs in the organisation but also on the benefits for individuals (Paille et al. 2010; Rahman et al. 2013). Employees assess the effectiveness of the training through the lenses of its relevance to address their individual needs. These needs can include the lack of knowledge, education, skills, and experience. Therefore, effective training programs are designed and integrated into the working process after the needs assessment and analysis.

Retention Theoretical Prediction

Many theoretical frameworks and models are used by scholars and practitioners in order to explain and support the phenomenon of employee retention in organisations. The specific theories that can be discussed as appropriate to describe the practices which can influence the employee perceptions, attitudes, and behaviours are the Human Capital Theory, the Social Exchange Theory, the Resource-Based View, the Price-Mueller Causal Model of Turnover, and the Rational Theory (Chen 2014; Holtom et al. 2008; Karanges et al. 2014). These theories are focused on employers’ motivation to apply certain strategies in order to retain employees, as well as on employees’ perceptions of associated HRM practices. The discussion of the appropriate theories is important to understand the connection between the employers’ efforts and expected retention.

Human Capital Theory

Researchers usually refer to the Human Capital Theory when they intend to explain employee retention with the focus on employers’ valuing the workers’ developed skills, abilities, experience, and knowledge. From this perspective, the Human Capital Theory “refers to the intangible resource of ability, effort, and time that workers bring to invest in their work” (Chen 2014, p. 356). When managers consider their employees as the valuable sources or the capital, they are inclined to create the necessary environments and appropriate conditions in order to guarantee that the employee stays in the organisation (Kyndt et al. 2009). In this context, retaining employees, managers focus on preserving not only the intellectual capital but also the social and emotional capital in order to increase the company’s competitiveness (Chen 2014). According to Larsson et al. (2007), the Human Capital Theory explains why employers try to prevent the increasing turnover rates and absenteeism among employees. The reason can be found in proportionally increased costs associated with retaining the human capital in the organisation.

According to the theory, the workforce is discussed as the beneficial capital, and employees tend to work better and demonstrate the higher level of commitment when employers invest more in the resources’ development and interests (Donate, Pena & Sanchez de Pablo 2016). Such vision of the employer-employee relations associated with the aspect of the retention “may cause both parties to make appropriate human capital investments, thereby reducing employees’ turnover and increasing attachment” (Huang, Lin & Chuang 2006, pp. 495-494). Much attention is paid to regulating the relations between leaders and employees according to this theory. On the one hand, the “human capital provides organisation with an important source of sustainable competitive advantage” (Beh & Loo 2013, p. 158). On the other hand, the treatment of employees as a capital requires the certain responsive actions. Therefore, according to Rahman and Nas (2013), it is possible to state that the Human Capital Theory allows focusing on the behaviours of both employers and employees in their attempts to address the needs and interests of each other.

An employee is also an important agent in the relations explained with references to the Human Capital Theory because he or she usually evaluates those benefits and rewards that can be proposed by the management. The evaluation is an important stage of the recruitment and retention process according to this theory, as it is noted by Beh and Loo (2013) and Chen (2014). The focus is usually on the compensation, rewards, training and development, fair performance appraisal, and possible promotion opportunities that are evaluated by both employers and employees in order to make final decisions (Huang et al. 2006). From this perspective, it is important to pay attention to the fact that employees view their career opportunities referring to monetary and psychological factors, and the Human Capital Theory is important to explain how the employers’ efforts to promote the human capital in the firm can influence the employees’ job satisfaction and their desire to work in the concrete organisation during a long period of time.

Social Exchange Theory

The main premises and aspects of the Social Exchange Theory were formulated by Blau (1964) in his writings on the social life; still, these principles were adapted to the business world and economics in order to explain the nature of relationships between employers and workers that are based on the exchange of social and intellectual goods (Karanges et al. 2014; Tzafrir et al. 2004). The theory is based on the idea that employees’ productivity and performance can improve if they perceive the feedback from employers as positive, and this feedback can be presented in the form of HRM practices that are oriented to increasing the employees’ potential (Chew & Chan 2008). Haley, Flint, and McNally (2013, p. 75) state that “drawing on social exchange theory, we contend that employees’ perceptions of the monitoring systems employed by their organisations affect their exchanges with their organisations.” In their study, they continue examining the issue and state that the “social exchange involves a continuous exchange of benefits over time in which both parties feel obligated to reciprocate” (Haley et al. 2013, p. 76). Thus, the positive behaviour of one person can stimulate the positive behaviour of the other person, and it is possible to expect the further social exchange.

In this study, the focus is on employers and employees as the main actors of this type of social relationships. Therefore, the Social Exchange Theory provided the background to such HRM techniques and approaches as recognition, reinforcement, empowerment, investment, and rewards for the purpose of increasing performance and productivity of employees. In his research, Tzafrir et al. (2004, p. 630) note that the “social exchange is based on the form of reciprocity namely we help those who help us.” While referring to the principles of the Social Exchange Theory, a manager can successfully improve the retention practices with the focus on changing the HRM practices to provide employees with more benefits. The result will be the positive changes in the performance of employees. Chew and Chan (2008, p. 513) explain this phenomenon while stating that “employees interpret HR practices as indicative of the personified organisation’s commitment to them.” However, investing in others, managers cannot guarantee that the positive feedback can be received. It is important to pay attention to the fact that the “social exchange emphasises the development of relations over time and indicates that a successful social exchange circle involves both rust and uncertainty” (Tzafrir et al. 2004, p. 630). As a result, there is an area for uncertainty in debates because of different assumptions regarding employers’ and employees’ behaviours.

Karanges et al. (2014, p. 331) state that it is possible to expect positive reactions of employees on changes in HRM approaches because “social exchanges involve a sequence of interactions between two parties that produce personal obligations, appreciation, and trust.” As a result, “positive and fair exchanges between two parties (individuals or groups) result in favourable behaviours and attitudes,” and it is possible to predict certain behaviours in all actors participating in the process (Karanges et al. 2014, p. 331). In addition, managers can discuss the employees’ positive actions and behaviours as reinforcers for the further improvement of conditions and retention practices. Thus, the employer’s decision can change depending on the employees’ behaviours, as well as workers’ performance depends on employers’ actions.

The outcomes of implementing such HRM approaches are explained with references to the theory because according to Paille (2013, p. 769), “employees exchange desirable outcomes in return for fair treatment, support or care.” If an employee recognises the reward for the contribution to the organisation as relevant and desired, there are more opportunities for retaining this employee. According to Harris, Wheeler, and Kacmar (2009, p. 372), the risks that the employee will leave the employer who empowers and supports him or her are minimal because employees can feel demonstrate their commitment and feel obligation to stay with the firm that supports their interests. Thus, the Social Exchange Theory was actively used by many researchers to support their conclusions regarding the relationships between employers’ activities and workers’ turnover intentions.

Resource-Based View

The Resource-Based View is referred to in the management literature in order to explain how employers regard the internal resources of the organisation. Thus, internal processes and practices can influence the successfulness of managing such resources as the workforce (Chen 2014; Tzafrir et al. 2004). While concentrating on the Resource-Based View in the organisational environment, Tzafrir et al. (2004, p. 630) note that “the resource-based perspective encourages a shift in emphasis toward the inherent characteristics of employee skills and their relative contribution to value creation.” In addition, according to Chen (2014, p. 356), the Resource-Based View followed in the company, “competitive advantage depends on the valuable, rare and hard-to-imitate resources”. From this perspective, managers tend to adopt strategies and approaches that are effective in order to address their valuable human resources and increase the competitiveness. For this purpose, much attention is paid to developing HRM practices that can be used in order to develop the employees’ skills (Presbitero, Roxas & Chadee 2016, p. 636). The researchers agree that positive changes in the employees’ skills lead to increasing the organisation’s potential and the overall competitiveness (Presbitero et al. 2016; Tzafrir et al. 2004).

According to this theory, organisations choose to invest in the development of internal resources, and they focus more on their retention because these resources are difficult to imitate, and they directly service to increase the competitive advantage of the firm (Presbitero et al. 2016, p. 636). Colbert (2004, p. 343) adds to the discussion of the theory in the context of HRM while noting that the Resource-Based View states “a firm develops competitive advantage by not only acquiring but also developing, combining, and effectively deploying its physical, human, and organisational resources in ways that add unique value and are difficult for competitors to imitate.” From this point, it is necessary to state that the variety of approaches and techniques to value resources and address their needs can be different as employers can focus on developing the work-life programs and specific HRM practices. According to Lengnick-Hall et al. (2009, p. 68), these specific strategies can be successful to retain employees. However, the Resource-Based View limits managers in proposing the programs for employees because the main focus is on the development of valuable resources in terms of their development in order to guarantee that each step in the HRM practice leads to making the resource even more valuable and competitive (Colbert 2004; Lengnick-Hall et al. 2009). Therefore, such practices as the reinforcement, empowerment initiatives, and promotion opportunities are often not applied, and this fact can influence the overall retention negatively.

Price-Mueller Causal Model of Turnover

In the 1980s, Price and Mueller proposed a comprehensive model of turnover. The model “identified the antecedents of job satisfaction and intent to leave” (Holtom et al. 2008, p. 239). Thus, the researchers determined how job satisfaction can be associated with the employees’ intentions to leave the organisation. In their model, Price and Mueller focused on the factors that could influence the workers’ decisions regarding their job. Among these factors, kinship responsibility, positive and negative affectivity, the opportunity, the availability of training, the adequate promotion, and job involvement were determined as the main causes to affect the employees’ decisions (Holtom et al. 2008, p. 239). Managers chose this theory in order to explain for concrete factors could influence the turnover rates in companies while preparing the appropriate measurements and assessments (Holtom et al. 2008; Hom et al. 2012).

It is important to note that the theory tends to explain the turnover intention through the lenses of not addressed expectations and the low level of the job satisfaction because employees do not experience the enough opportunity, autonomy, justice, and involvement in the organisation’s team (Hom et al. 2012). In addition, strict family ties and the increased level of routinisation at the workplace can cause employees to make the decision regarding the further work in the organisation (Hom et al. 2012; Hom et al. 2012). In spite of the fact that this model explains that high level of turnover is associated with the lack of participation, opportunity, promotion, and involvement causing the job dissatisfaction, the model does not address HRM practices that can be used in order to improve the situation and make the experience of employees more positive. This model is used only in the limited number of studies as the framework to explain the problem of turnover with the focus on the retention strategies applied in the organization.

Rational Theory

The principles of the Rational Theory or rational decision-making theory were formulated by Simon (1945) and then used by researchers in order to discuss how employers make decisions regarding recruiting and retaining their employees (Gberevbie 2010, p. 66). The theory is based on the problem of making decisions. According to Tohidi and Jabbari (2012, p. 826), decisions represent “how we get things done and move forward.” In addition, the researchers note that “management is upon rationality and rational actions” (Tohidi & Jabbari 2012, p. 826). The focus is on the rational actions of employers and managers that are performed in order to guarantee that the organisation follows the set strategy. According to the theory, all decisions made in organisations are rational in their nature; therefore, the ideas to retain employees and to adopt the practices that can promote the commitment and retention are supported by the rational grounds (Gberevbie 2010). From this theoretical perspective, managers make decisions regarding employees and their retention while selecting the actions that can lead to achieving the certain strategy. Therefore, such approach to management is regarded as rational (Gberevbie 2010).

The Rational Theory is used by theorists and managers in order to explain their policies regarding employees when these policies are formulated as a result of the decision-making process. Abdullah, Ahsan, and Alam (2009, p. 65) note in their study that “companies are now trying to add value with their human resources and human resource (HR) department has been set up in order to manage their human capital.” Thus, the theory allows explaining why HRM departments extend and what principles and tools are used by managers in order to achieve the expected results and set goals.

Reasons to Refer to Human Capital Theory and Social Exchange Theory

The Human Capital Theory is used by researchers in order to explain how certain monetary and psychological rewards can affect the employees’ motivation. These rewards are usually associated with the implementation of the HRM practices that can cause changes in employees’ perceptions and behaviours, as well as intentions to remain with organisations (Beh & Loo 2013; Huang et al. 2006). While focusing on the necessity to explain how HRM practices and perceptions of employees can influence their turnover intentions and the overall retention, it is important to refer to the Human Capital Theory. The theory provides the background to understand how employees’ visions of practices can further lead to increased retention in the organisation where these practices are integrated into the strategy (Chen 2014). It is typical of public organisations in Qatar to include financial components in employer-employee relations in order to demonstrate that employees are valued (Al-Horr & Salih 2011). This approach is used in the work with nationals. Thus, managers choose to create the appropriate conditions for talents among the Qataris in order to guarantee their retention. This specific approach is directly explained with references to the principles of the Human Capital Theory.

Another theory that should be selected as the background for this study is the Social Exchange Theory that is inclined to explain the nature of relations between employers and employees as an exchange of efforts, outcomes, and rewards (Tzafrir et al. 2004). In Qatar, the implementation of this theoretical framework can be viewed through the lenses of HRM practices that are usually launched in the public sector in order to reinforce employees’ productivity, increase their job satisfaction, and influence the attitude to the institution (Al-Khatib & Al-Abdulla 2001; Karanges et al. 2014). In rapidly developing countries, the dependence of employers and employees on each other is significant, especially in public sector organisations (Afiouni, Ruel & Schuler 2014). This issue is explained with references to the Social Exchange Theory (Chew & Chan 2008). Thus, while reviewing the situation in Qatar with the help of this theory, it is possible to state that public organisations are the main sources of employment for nationals in Qatar, and employees respond to the possibility of being employed while using their competences and creativity (Afiouni et al. 2014; Forstenlechner 2010). In their turn, managers in these organisations receive the opportunity to attract the high-skilled workers or talents, and they adopt certain strategies in order to address the employees’ needs. According to the theory, employee retention strategies can be viewed as social exchange concepts (Karanges et al. 2014). Thus, employees choose to stay with those organisations where managers value their efforts and contribution.

If the Human Capital Theory and Social Exchange Theory can explain the relationship between perceptions of HRM practices, employees’ attitudes, and turnover intentions directly, such theories as the Resource-Based View, Price-Mueller Causal Model, and the Rational Theory should be discussed as supportive because their aspects cannot be used in order to explain the relationships in the specific context of Qatar (Colbert 2004; Gberevbie 2010). Thus, the Resource-Based View is effective to explain the application of certain HRM practices in organisations in order to promote internal resources, but it does not demonstrate the specific correlation between employers’ investments in HRM practices and further employees’ behaviours. The problem is in the fact that the Resource-Based View refers to the idea of investing in employees’ skills, and it does not provide the answer to the problem of promoting the retention in the company (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2009). The other mentioned theories are also non-appropriate to explain the relationship between HRM practices and the phenomenon of retention in the public sector organizations of Qatar.

Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviours

The implementation of HRM practices can provoke different emotions and visions in employees. Researchers and practitioners are interested in such reactions as positive or negative perceptions; individuals’ attitudes, including job satisfaction; behaviours, including turnover intentions (Hasin & Omar 2007; Katou 2013). The reason is that each HRM practice provokes a certain reaction and influences the following behaviours. Managers are interested in stimulating employees’ motivation and helping them work effectively and improve their performance. Therefore, much attention is paid to monitoring changes in employees’ attitudes and using strategies that can be appropriate in order to contribute to workers’ commitment and improved performance (Choi & Lee 2013; Gberevbie 2010). The existing literature in the field of HRM provides different perspectives to discuss such phenomena as job satisfaction, turnover intention, and retention in the organisational context.

Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction is a complex attitude that employees have in relation to their job positions. According to Choi and Lee (2013, p. 576), job satisfaction is “the feelings and the appraisal employees have toward the jobs which are assigned to them.” The researchers continue that this attitude can be stimulated by certain HRM practices used by managers. These practices include the compensation programs and empowerment initiatives (Choi and Lee 2013). In their study, Bockerman and Ilmakunnas (2012, p. 246) emphasise that job satisfaction is “a narrower measure of well-being than happiness because it covers only well-being that is related to the job.” Harris et al. (2009) state that satisfied employees may demonstrate the interest in the organisational culture, cooperation, and teamwork. The levels of their productivity and performance can increase, and they can have the lower turnover intentions. In their research, Katou (2013) and Marescaux, De Winne, and Sels (2012) also note that if employees are not satisfied with their job, tasks, position, or team, the levels of absenteeism can increase proportionally to the decreased quality of work. Such conditions stimulate workers to develop turnover intentions. According to Bockerman and Ilmakunnas (2012, p. 246), “job dissatisfaction leads to quit intentions and actual separations.” Thus, managers try to address job satisfaction because this factor reflects the employees’ attitudes to their positions and duties. Moreover, strategies associated with increasing job satisfaction of employees are often more cost-effective than strategies oriented to resolving the issue of turnover and problems associated with recruitment and attraction of new talents (Bockerman & Ilmakunnas 2012; Katou 2013).

In their study, Hasin and Omar (2007, p. 23) remarked that job satisfaction is “essentially any combination of psychological and environmental circumstances that cause a person to produce a statement, “I am satisfied with my job”. It is important for employees to appraise their jobs and feel the emotional satisfaction associated with daily professional duties and experiences. In this context, satisfaction can be reflected in the employees’ feelings of pride and enthusiasm, as well as their dedication (Hasin & Omar 2007). Majumder (2012) concluded in the study that employees focus on both emotions and logical conclusions regarding their jobs while thinking about their job satisfaction. These two factors are important in order to state whether a person is satisfied with duties performed daily.

Satisfied employees can concentrate on their tasks and responsibilities fully and their performance is higher (Den Hartog et al. 2013; Paille, Bourdeau & Galois 2010). There are also cases when job satisfaction causes persons to exceed their duties and become more initiative. In organisations, managers value such behaviours of employees, and it is possible to promote the further satisfaction and commitment while adopting effective HRM practices. Job satisfaction can also be viewed as a specific feeling of pleasure that can be caused by extrinsic motivators like salary and other material rewards and intrinsic motivators like challenging tasks, promotion, recognition, development, and collaboration among others (Edgar & Geare 2005; Paille et al. 2010). In their study, Daniel & Sonnentag (2016) also focus on job satisfaction that is associated with the work-and-life balance practices followed in organisations. Thus, researchers concluded that job satisfaction can be caused by the nature of job and assigned tasks, but in most cases, job satisfaction is a result of HRM practices that allow the increases in compensation, the promotion, and the development that stimulate individuals’ self-esteem (Gilmore & Turner 2010; Hausknecht et al. 2009; Huang et al. 2006).

Retention

The term ‘retention’ is used by managers and researchers in order to identify the process of retaining employees in the organisation. In the sphere of HRM, retention is also viewed as a set of strategies and approaches that can be used by HR managers in order to retain talents and decrease the turnover rate (Glen 2006). ALDamoe et al. (2011, p. 79) focused on the idea that “employee retention is a voluntary effort by any organisation to provide an environment which tends to keep or retain employees for a long period.” However, researchers’ ideas regarding the managers’ use of retention practices differ. In their study, Bambacas and Kulik (2013) note that the retention is a practice that is used as the turnover prevention in organisations. Juhdi, Pawan, and Hansaram (2013) support this idea and pay attention to the fact that managers often start implementing changes in HRM practices only when the turnover rate tends to increase while causing the growth in costs associated with retaining employees. On the contrary, Gberevbie (2010) notes that retention is a practice that is followed in the company continuously, for the purpose of improving the climate in the organisation and creating the appropriate conditions for employees.

In their work, Huang et al. (2006, p. 492) mention that “the decision to stay or go involves evaluating cost and benefits” by employees, and the effectiveness of retention depends on the quality of HRM practices and proposed benefits. Thus, “if the present value of the returns associated with turnover exceeds both monetary and psychological costs of leaving, workers will be motivated to change jobs” (Huang et al. 2006, p. 49). In this case, it is possible to speak about the ineffective retention policy followed in the organisation. In their turn, Holtom et al. (2008) are inclined to associate the retention tendencies with more global factors. The researchers state, “a number of trends (e.g., globalisation, increase in knowledge work, accelerating rate of technological advancement) make it vital that firms acquire and retain human capital” (Holtom et al. 2008, p. 232). The mentioned factors influence the HR managers’ approach to attracting employees and maintaining their interest in the position.

While discussing the role of retention practices for organisations, Chen (2014, p. 357) concludes that “the organisation will be faced with a significant loss such as reduction in organisational performance if the turnover of talented employees is high.” Therefore, retention practices are important to influence the relations of managers and employees, as well as to affect the workers’ performance and productivity (Snape & Redman 2010). Chen (2014, p. 357) pays attention to the fact that the “successful employee retention helps preserve the knowledge within an organisation. If the employee leaves the organisation, a knowledge gap is generated.” When employees’ needs are not addressed, and retention practices do not work, employers face a challenge of losing talented or skilled workers. As a result, managers continue to look for HRM practices that can be discussed as most effective in order to not only attract but also retain employees and save costs of the company.

Turnover Intention

The term ‘turnover’ is used by managers in order to describe the phenomenon associated with intended changes in the number of hired and fired employees. In addition, this term is also used in order to demonstrate how many employees leaved jobs voluntarily (Cho & Lewis 2012). Yousaf, Sanders, and Abbas (2015) mention in their work that it is important to distinguish between the term ‘turnover’ that is used to determine an act and the term ‘turnover intentions’ that is used to describe the employees’ decision. In this context, the term ‘turnover intention’ is used to speak about the situation when employees decide to change their jobs. This term also covers such actions as the job search and the actual quit. According to Gberevbie (2010, p. 65), “causes of labour turnover could be explained based on number of factors” that include “job dissatisfaction, lack of organisational commitment, comparison of alternatives, and intention to quit.” Lai and Kapstad (2009) and Newman, Thanacoody, and Hui (2011) note that in spite of the causes of turnover, managers are inclined to implement the variety of practices to predict turnover intentions in employees because of high costs associated with turnover. Gilmore and Turner (2010) conducted the study and found that employers lose millions of dollars annually because of employees’ absenteeism, the low quality of performance, and the lack of commitment. Therefore, HRM practices are regarded as cost-efficient approaches to decreasing the turnover rates. According to Gavino, Wayne, and Erdogan (2012, p. 678), “one of the purposes of this investment in HR practices is to align employee behaviors with corporate objectives by motivating employees to display behaviors that benefit the organization.” In most cases, such investment is reasonable.

Turnover intentions and decisions are usually based on certain backgrounds associated with the policies followed in the organisation, its culture, or HRM practices (Glen 2006). The predictable causes of turnover intentions are the low salary; inappropriate working conditions; the unfair performance management; the lack of training; bureaucratic systems associated with the training, development, and promotion (Kashyap & Rangnekar 2014; Presbitero et al. 2016). Therefore, managers can affect the turnover rate while working to improve the conditions for employees and proposing certain benefits to them. It is possible to change the employees’ perceptions, experiences, and attitudes with the help of practices that can guarantee positive feelings (Dysvik & Kuvaas 2010). Such approaches can lead to decreased turnover intentions among employees (Hom et al. 2012, p. 832; Slatten, Svensson & Sværi 2011). According to Paille, Bourdeau, and Galois (2010, p. 43), “employees who feel supported by their employer are less likely to examine outside job possibilities and lack diligence in the workplace.” From this point, the employees’ turnover intention can be affected with the help of certain actions made by managers because they can influence the employees’ personal assessment of their job.

According to Lai and Kapstad (2009), when managers need to evaluate how employees react to their HRM practices used to decrease the turnover, they should refer to job-related perceptions, visions, and emotions. The reason is that negative emotions can directly lead to the development of turnover intentions (Flint, Haley & McNally 2013; Rehman 2012). Brunetto et al. (2012) pay attention to the fact that turnover intentions can be viewed as psychological or emotional indicators of the employees; attitudes to the job, and these reactions need to be addressed with the help of implemented retention practices and strategies. In their studies, Rose and Gordon (2010) and Tangthong (2014) propose the regular monitoring of turnover intentions in order to understand what HRM practices can have the most positive effect on employees and their retention. These actions are important in order to decrease the number of employees who plan to withdraw from organisations causing the increases in the labour costs for employers.

Problem of Retention

In the HRM literature, the term ‘retention’ is usually used in along with the term ‘turnover intention’. In spite of the fact that retention is the strategy used by managers in order to address the employees’ turnover intentions, the problem is in assessing the effectiveness of this strategy. According to Tangthong (2014), in order to speak about the retention in the concrete organisation, it is relevant to assess or measure the turnover rate or focus on the turnover intentions of employees. Employees’ turnover intentions are viewed as influenced by their perceptions of HRM practices and their effectiveness. These reactions can be tested in contrast to the phenomenon of retention. In order to conclude about the retention in the firm, it is important to refer to the employees’ intentions to stay or quit that are based on their emotions, feelings, and attitudes (Rathi & Lee 2015; Tremblay, Dahan & Gianecchini 2014). From this point, researchers cannot measure retention and its level directly, and they refer to employees’ turnover intentions as indicators of possible problems in the HRM of the organisation (Govaerts et al. 2011; Lai & Kapstad 2009).

In order to support this idea, Yamamoto (2013) states that it is almost impossible to measure the retention without direct references to the psychological aspects of employees’ attitudes, opinions, and behaviours. In his study, Yamamoto (2013) refers to the term ‘turnover intention’ as an indicator to resemble the ‘retention’ in relation to the certain organisation. In order to discuss how HRM practices or strategies can influence the employee retention in measurable terms, it is important to assess employees’ feeling, visions, and emotions (Gilmore & Turner 2010; Hausknecht et al. 2009). Therefore, in the majority of studies where the problem of retention is discussed, turnover intentions are measured as main indicators of the turnover rate and effectiveness of the retention strategy in the company (Taplin & Winterton 2007). From this perspective, the term ‘turnover intention’ can also be used in order to explain the employees’ motivation associated with staying with the organization or quitting (Dewettinck & Van Ameijde 2011). Employees’ perceptions regarding the HRM practices are important to be measured in order to state whether workers are willing to leave or remain with the company under certain circumstances and with references to the outcomes of different HRM practices (Cho & Lewis 2012). In the recent literature, the problem of retention in private and public organisations is discussed with references to the turnover intentions, and this tendency is followed by many researchers who aim at measuring the effects of certain HRM practices on employees, their performance, retention, interest in the organisation, commitment, and dedication (Rasouli et al. 2013; Tsai, Edwards & Sengupta 2010; Yamamoto 2011). These aspects are associated with the sphere of employees’ emotions and attitudes that lead to certain decisions and behaviours that can influence retention in their turn.

Relationship between HRM Practices and Employees’ Perceptions, Attitudes, and Behaviours

In previous studies on the problem of retention and high turnover rates in organisations, researchers aimed to find the relationships between HRM practices implemented according to HRM policies and guidelines and the employees’ behaviours. In their works, researchers concentrate on finding the relationships between these phenomena of concepts while following three directions (Den Hartog et al. 2013; Osman, Ho & Galang 2011). According to the first direction, it is possible to find the relationship between HRM practices and the employees’ perceptions of these practices that often differ from the managers’ expectations (Rasouli et al. 2013; Tsai et al. 2010). The second direction is the focus on finding the relationship between HRM practices and the employees’ attitudes, including job satisfaction (Edgar & Geare 2005; Singh et al. 2012). The other group of researchers concentrated on finding the direct relationship between HRM practices and the employees’ turnover intentions or other types of behaviours associated with the problem of retention (Bartel 2004; Gilmore & Turner 2010; Yamamoto 2011).

Relationship between HRM Practices and Employees’ Perceptions

Researchers distinguish between positive and negative employees’ perceptions of their organisations that can influence the overall performance and productivity, as well as the climate in the company (Rasouli et al. 2013; Tsai et al. 2010). Theorists and practitioners name effective and ineffective HRM practices as the main factors that can influence the employees’ perceptions and attitudes (Zheng, O’Neill & Morrison 2009; Yamamoto 2013). However, Rasouli et al. (2013) note that employees are often influenced not only by external but also internal factors, and they need to be taken into account by managers who plan to implement certain HRM practices. According to Chew and Chan (2008), employees are inclined to demonstrate the positive attitude to the organisation when their individual or personal values are correlated with the values promoted in the firm.

While studying perceptions of employees related to their jobs, HRM, and everyday activities, Jiang et al. (2015) found that effective HRM practices that are implemented to demonstrate how the organisation can value and pay attention to the interests of employees serve to improve the workers’ perceptions. Such practices as recognition, empowerment, promotion, rewarding, development, training, as well as performance appraisal and management are effective to ensure employees that their efforts are valued, and Zheng et al. (2009) and Antwi et al. (2016) also pointed to the positive relationship between the implementation of these HRM practices and positive changes in the employees’ perceptions of their work conditions and organisations in terms of status and commitment.