Literature Review

Since the early beginnings of capitalism, the family has constituted a primary vehicle of economic production. In spite of the many significant technological changes that have taken place since those early times, recent literature shows that the family remains a critical force behind many modem work organizations. In the United States alone, for example, over 90 percent of all corporations (including 35 percent of the Fortune 500) are either owned or controlled by a family. (Zahra, 2004)

Yet despite the prevalence of family businesses, our understanding of this type of organization remains rather limited — particularly with regard to its fundamental structure. In response to this state of affairs, this article examines some basic sociological properties of family firms, focusing on how structural contradictions that are built into their fiber affect the founder’s ability to effectively manage relatives who work in the business. The article also provides some practical guidelines for entrepreneurs who head family firms. Human resource practices play a decisive and pivotal role in the firms’ advancement whether it is family or nonfamily firm.

The literature on family business sometimes gives the impression of being their irrational entity (Hollander and Elman, 1988). This is not the least the case in relation to strategy processes. In many respects, strategy processes are the same in all businesses, family dominated or not (Sharma et al., 1997). The key difference is that, in the family business (Westhead, 1997) all stages of the process are likely to be influenced by family values, goals and relations (Holland and Boulton, 1988). Moreover, the close inter-relationship between family and business often leads to a mix up of issues from the different contexts (Davis and Stern, 1996).

Since relatively little research has been conducted on family business strategy (Harris et al., 1994), the understanding of how these influences affect strategy processes in family business is quite limited (Sharma et al., 1997). Even so, the fact that family relations do impact upon strategy processes in family businesses seems to be enough to label them ‘irrational’. The meaning of rationality is, however, seldom discussed. Instead it seems to be implicitly taken for granted.

What is thought of as ‘rational’ is most often calculative rationality (Sjöstrand, 1997), referring to actions that are the most ‘efficient means for the achievement of given ends’ (Hargreaves Heap, 1989:4). This account of rationality originates from economics and builds on the notion of ‘economic man’. Starting with a well-defined goal the economic man evaluates all possible alternatives from which, the one that maximizes his utility, is chosen.

This mode of rationality has its main focus on the outcome of action and requires an analytical, calculative agent who has consistent preferences, perfect information, is able to cope with extreme complexity, and who is not socialized into any traditions/norms but is totally free to act (Granovetter, 1985; Mäki et al., 1993; Hollis, 1994; Sjöstrand, 1997). ‘With perfect information and correct computing, preference is automatically transmitted into outcome so as to solve the maximizing problem. The agent is simply a throughput’ (Hollis, 1994)

Even though the assumptions of economic man can be accused of unrealism (Sjöstrand, 1997; McCloskey, 1998), the calculative account of rationality still dominates the literature on strategy and management (Whittington, 1993; Sjöstrand, 1997; Mintzberg et al., 1998). Traditionally, strategy has been viewed as the sequential formulation and implementation of an organization’s long-term goal to achieve profit maximization. This is the essence of economic rationality. Strategy has typically been portrayed as a plan, a rational search for the most efficient way of achieving this goal based on objective responses to environmental demands – formulated by top managers.

This perspective on strategy, often referred to as the ‘Classical’ (Whittington, 1993) or ‘Rationalistic’ (Johnson, 1986), does not put much consideration on the implementation phase. Instead, the accomplishment of the intended strategy is implicitly taken for granted (Whittington, 1993; Mintzberg et al., 1998) and the process behind the realized strategy is, by and large, ignored.

Considering the domination of the mono-rational, classical perspective on strategy, the condemnation of family business as ‘irrational’ is perhaps not so surprising. It does, however, limit understanding of strategy processes. Therefore, scholars in the field of strategy have pointed out the importance of understanding strategy processes from other perspectives which are ‘concerned less with prescribing ideal strategic behavior than with describing how strategies do, in fact, get made’ (Mintzberg et al., 1998:6). These perspectives represent a contextual view on strategy. Far from being planned, strategies emerge as a pattern in a stream of actions (ibid.).

This view is close to the one held by economic sociologists who argue that economic action, like any other form of action, is socially situated. It is embedded in ongoing networks of personal relationships and is expressed in interaction with other people (Granovetter, 1985; Mäki et al., 1993). A focus on the outcome of action (calculative rationality) is thereby insufficient and has to be complemented by non-calculative, social accounts of rationality with a focus on process and meaning (Sjöstrand, 1997; McCloskey, 1998).

The questioning of economic rationality has led to an increased interest in the notion of multi-rationality among strategy researchers (Whittington, 1993; Sjöstrand, 1997; Regnér, 2001; Volberda and Elfring, 2001). Doubtful about the empirical relevance of the classical perspective on strategy, Regnér (2001:44) argues that strategic development is better understood as ‘an interwoven process involving diverse rationalities and strategies simultaneously rather than individual rationalities and strategies as distinct lumps in a process of episodic stages’.

Relating rationality to degrees of complexity he further claims that the more complex the strategic process, the more important are rationalities that take context and process into account. Moreover, each strategy process has to be understood in terms of its specific composition, or configuration of rationalities: ‘A strategy process could involve all sorts of complexities and, thus, rationalities and therefore it does not make sense to analyze it according to a single rationality view’ (Regnér 2001)

In line with the criticism of the mono-rational, classical view of strategy, the aim, in most of cases is to contribute to a better understanding of strategy processes in family businesses through a multi-rational perspective. In order to investigate how accounts of rationalities are interrelated and shaping strategy processes in a small, family business, the case of ACTAB is presented and analyzed. A business in the second generation was chosen in order to capture the complexity, role integration and multi-rationality that are likely to be present when members of two generations together own and manage a company.

For many people, work and family roles have become notable sources of conflict, as the demands associated with each domain affect each other (Kanter, 1989). Indeed, balancing work and family demands is a major challenge for many organizations (Ingram and Simons, 1995).

Given that both work and family factors are potent contributors of stress as well as significant sources of emotional well-being, a number of models have been developed to explain the interface between work-to-family conflict and well-being (Frone et al., 1997; Parasuraman et al., 1996). These models depict linking mechanisms or causal connections between specific work and family constructs (Edwards and Rothbard, 2000). Although these models differ in many respects, it appears that none have focused on cross-national phenomena nor examined, quantitatively, owners of family-controlled businesses.

Strategic Human Resource Management define the activities of management, and whatever the organizational processes are, an essential part of the process of management is that proper attention be given to the Human Resource function. The human element provides a major part in the overall success of the organization. Therefore, there must be an effective human resource function. In the past, most organizations viewed Human Resource Management (HRM) as an element function that is an activity that is supportive of the task functions and does not normally have any accountability for the performance of a specific end task.

Because of the emphasis on analysis and precision there is a tendency for strategists to concentrate on economic data and ignore the way in which human elements and values can influence the implementation of a strategy. “Economic analysis of strategy fails to recognize the complex role which people play in the evolution of strategy…strategy is also products of what people want an organization to do or what they feel the organization should be like.” (Schermerhorn, 2001)

Understanding the strategic potential of HRM is a relatively recent phenomenon. Strategic HRM attempts to bring HRM to the boardroom. It requires personnel policies and practices to be integrated so that they make a coherent whole and also that this whole is integrated with the business or organizational strategy. Strategic HRM has evolved through three main stages. (Gan, Marie 2002) Up until the mid 1960’s HRM comprised mainly a file maintenance stage with most emphasis on selection, recruitment, screening and orientation of the new employee. They also looked after employee-related data and organized the Christmas party.

The second stage, government accountability developed with the arrival of the Civil Rights Act and evolved with subsequent laws. To avoid costly legal battles, the HRM function gained in stature and importance. The third stage in HRM development which began in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s was the realization that effective HRM could give an organization competitive advantage. Within this stage HRM is viewed as important for both strategy formulation and implementation. For example 3M’s noted scientists enable the company to pursue a differentiation strategy based on innovative products. At the competitive stage, then, human resources are considered explicitly in conjunction with strategic management, particularly through the mechanism of human resource planning (Thomas, 1986).

Human Resource Strategies currently focus around quality, customer orientation, flexibility, commitment, involvement, leadership, team working and continuous learning (Derek Torrington, 1995). These themes of integration and a central philosophy of people management have been drawn out by a number of writers, for example Handy et al (1989) and Hendry and Pettigrew (1986). As early as 1983 Baird et al went one step beyond this and argued that there can be no organizational strategy without the inclusion of human resources. Firms such as 3M were at the forefront of a trend towards recognizing human resources as a crucial element in the strategic success of organizations (Harold, 1985).

Managers within the HRM function participate directly in strategy formulation. They also help co-ordinate the HR aspects of strategy implementation. The extent to which the human resource function is involved in both organizational and human resource strategy development is dependent on a range of factors. (Gibb, 1996) The Personnel Role in the Organization The degree of involvement in strategy is dependent on the status and level of regard the Human Resource function is given in the organization. One way this can be assessed is by viewing the role of the most senior personnel officer.

Buller (1988) found that the degree of integration between organizational and human resource strategy was influenced by its philosophy towards people. Organizations that operate in a stable predictable environment face little pressure to change whereas a turbulent environment will demand the organization strives to find new ways of doing a range of things. It is when operating in this latter scenario that organizations are more likely to have the Human Resource function involved in strategy and planning. (Katherine, 1991)

Any organization is made up of groups of people. An essential part of management is coordinating the activities of groups and directing the efforts of their members towards the goals and objectives of the organization. This involves the process of leadership and the choice of an appropriate form of behavior. The manager must understand the nature of leadership and the factors which determine the effectiveness of the leadership process (Mullins, 1982).

There is no substitute for leadership. But management cannot create leaders. It can only create the conditions under which potential leadership qualities become effective, or it can stifle potential leaders (Peter, 1995). Strategic HRM ensures that the right conditions are created by enabling the human resource functions the chance to have a say in the development of the business and the objectives its sets. Without an effective Human Relations approach the necessary environment for leaders to develop does not exist. Much research has been performed on the need for a participative approach to leadership. (Irwin, David 2000) The earliest definitive proof came with research carried out at the relay assembly test room at the Hawthorne plant of the Western Electric Company of America (Roethsliger, 1999).

Subsequent to these discoveries was a distinct rise in the attention given to theories of individual motivation and therefore a more psychological approach to the strategies of an organization. This elevated the HRM function in the company and although many years before the term Strategic Human Resource Management came to fruition, it sowed the seeds and is supported by writers such as McGregor, Likert and Blake and Mouton who all realized the need for participative Human Resource functions in improving organizational effectiveness. An effective HRM function should ensure that positive performance is met with positive rewards.

This is brought about with efficient appraisal programs and the opportunity for the employee to, where practical, display signs of initiative. A feature of quality HRM is when each employee is fully aware of their premise for individual thought. This model of leadership is the path-goal theory, the main work on which has been undertaken by House and House and Dessler. The model is based on the belief that the individual’s motivation is dependent upon expectations that increased effort to achieve an improved level of performance will be successful, and expectations that improved performance will be instrumental in obtaining positive rewards and avoiding negative outcomes. (Schermerhorn, 2001)

Dawn also supports the same idea in the following words, “Little is known concerning human resource practices in family-owned firms and their effect on performance (Reid et al. 2002 in Dawn, 2006). Anecdotal evidence suggests that family businesses, rife with nepotism, eschew human resource practices” (Gersick et al. 1997 in Dawn, 2006)

Increased support for the need for effective appraisal was Goldsmith and Clutterbucks study of top British companies. This showed that managers at all levels pinpointed effective leadership at top management level as key to their own motivation and therefore the organizations success. Learning is the new form of labor. Continuous learning is a strategic theme which is increasingly apparent, if not the most critical (Derek, 1998). The same opinion is held by Dawn in these words, “HRM practices such as employment security, selectivity in recruiting, high wages, incentive pay, employee ownership, participation and empowerment, promotion from within, training, and skill development are just a few of the practices acknowledged as having great value to the organization” (Pfeffer 1994 in Dawn, 2006).

Garrat (1990) argues that for an organization to survive, learning in the organization has got to be greater or at least equal to the degree of change. Mintzberg’s proposition of emergent strategy also supports this statement. Strategy formulation can be seen as resulting from ready-fire-aim-fire-aim-fire rather than ready-aim-fire. People and organization s need to act in order to think as well as to think in order to act. To benefit from peoples actions an organization is needed that is open to the potential for learning and development that is available. An untrained workforce is, in the long run an inefficient use of funds and resources. (Samuel, 1992)

A business’s profits are affected as a result of this untrained work-force dilemma, and therefore, the organization must play an involved role in providing a solution. And it is not just the big corporation with deep pockets that needs to get involved, it is also the small and mid-sized family-owned business that needs to recruit and retain trainable, qualified talent.

This is the job of HRM and should form part of the overall organizations strategy. It must be accepted in the workplace that it is alright to make mistakes so long as learning has occurred and the same mistake will not be made in the future. HRM can then establish the employees that make the least mistakes and also those that learn most rapidly. Armed with this information, the HRM function can be involved in strategy by deciding which candidates should be given more authority. Multi-skilling is something of a buzz word in business. It describes highly trained members of staff, competent in a number of aspects of the organization. (Richard, 1983)

A key element to flexibility, it is highly productive for the organization. As part of the organizational strategy the HRM function is crucial to the effective implementation. In order to form successful strategy to respond to rapidly changing environments it is evident that the organization has to become a learning organization. Defined by Garrat this is: “An organization which facilitates the learning of all its members and continuously transforms itself.” People change is central to Organizational development and HRM. Through teaching and developing certain aspects of people in the organization, these changes are based on an overview of structure, strategy and technology.

Tom Peters (1992) says “Knowledge is the source of most value added.” (Tom Peters, 1992) If so then how do organizations accumulate and more importantly disperse this knowledge. The answer is through effective Strategic HRM. Facilities must in place so that the diffusion of knowledge can take place. Encouraging and developing each member at work is essential for individual and organizational health and is a major task of the HRM function. Recognizing and improving an individual’s talent and potential is essential so that the many roles and functions are achieved effectively. (Laurie, 1994)

The formulation and implementation of strategy is in some ways inimical to HRM. Most evidence and professional research seems to show that without the inclusion of the Human Resource function in strategy formulation then it becomes somewhat obsolete by the time it has filtered down through the hierarchy. (Kathryn, 1991) The involvement of this function is essential also to create the environment necessary for the evolution of leaders. Efficient recruitment, selection, appraisal and reward systems must be in place so that the best people for the job are selected and progress through the organization. Continuous learning is critical to Strategic HRM.

It is essential to get the most out of your staff and by training, evaluating and developing your employees through the process of HRM. With this, the organization is strategically better equipped to deal with any environmental changes that may affect the normally smooth operation of the organization.

Today’s HR professional have to focus not only on how to strategically position the firm globally to succeed in meeting the local customers desires and needs but to be able to “maintain the critical balance between a strong corporate culture and a local cultural differences”, (DDI, web source.).

To do so successfully, global business managers, which include human resource managers from both cultures, should be involved in the beginning stages of the global development of the company. Global companies rely on the efforts of employees from different countries. Every employee has different backgrounds and integrates to different cultures and these differences without doubt influence productivity and quality of work. In developing globalization organization there needs to be some consistency among the HR practices; creating corporate culture around the globe should be consistent with organization’s goals and visions. (DDI, web source.)

Technology is another factor that can change the functions in HR management. With the rapid changes in new technology there can be some challenges that the HR department faces. For example, implementing online resumes systems. Although, these types of systems can reduce the time and cost in hiring process, these types of systems require constant upgrades and new versions are released often. HR professionals must constantly adjust to these changes and learn new functions and features of the systems. “Companies that make an effort to improve their competitiveness by investing in new technology throughout the organization also invest in state-of-the-art staffing, training, and compensation practices”, (Noe et al., 2004)

The human resources department has to meet many challenges in order for a company to be successful. Among these challenges are maintaining a safe and healthy work environment for its employees. In order to meet this challenge the organization must ensure that all requirements have been abided by and that the proper employee training is given. A company that does not meet these requirements takes a chance of losing employees and therefore the whole company due to lawsuits and safety shutdowns. The HR not only needs to keep the workplace safe but also needs to reduce the stress levels of the employees.

Workplace stress has been proven to drastically reduce employee productivity. When productivity and service are lost, the company loses money, so keeping workers safe and happy is a challenge that needs to be met. Along with maintaining a safe environment, HR is continually changing its method of evaluating employees. By continually managing employees’ productivity and service levels, the company can provide quick and efficient feedback to the employee so that continual improvement can be made. This method replaces an annual evaluation method, which relies on a manager’s memory of an employee’s performance over an entire year.

This is flawed because a manager cannot possibly remember every positive or negative an employee makes over the entire year. This also does not contribute to continual performance improvement because the employee only gets feedback once a year and can make a change only once a year when the feedback is given. Emphasizing HRM practices in family owned SMEs Dawn, stance may be observed as such, “By placing importance on the human resource aspect of the firm, a family-owned SME might be able to effectively use HRM such that it has a positive impact on performance.” (Dawn, 2006)

A large loss in an organization’s profits is due to employee turnover. In order to minimize this loss, HR must improve the recruiting practices and the hiring practices within the organization. When the wrong hiring decision is made within an organization, the company not only has to worry about losses in productivity and decreasing profits but also must think about losses in employee enthusiasm and morale. Without a smiling employee to sell or provide a service, the company can lose valuable customers and take an even larger bite from profits. HR is increasingly finding itself in a global marketplace.

This means that HR professionals must have the necessary skills and knowledge to meet the global need. HR professionals are going to need to be highly educated and will have to take on increasing responsibilities. The future of HR is increasingly becoming an outsourced department within organizations where the HR professional has to take on more to ensure a companies success. To maintain a competitive edge, HR departments must adept to the constant changes and challenges in technology.

Human Resource Practices and Implications

Family firms come in many shapes and forms, ranging from the local “Ma and Pa” store to the huge multinational. In addition, family firms vary widely in their missions and strategies and in the markets in which they operate. Despite this diversity, however, one undeniable fact holds true for all family firms: These organizations exist on the boundaries of two qualitatively different social institutions —the family and the business.

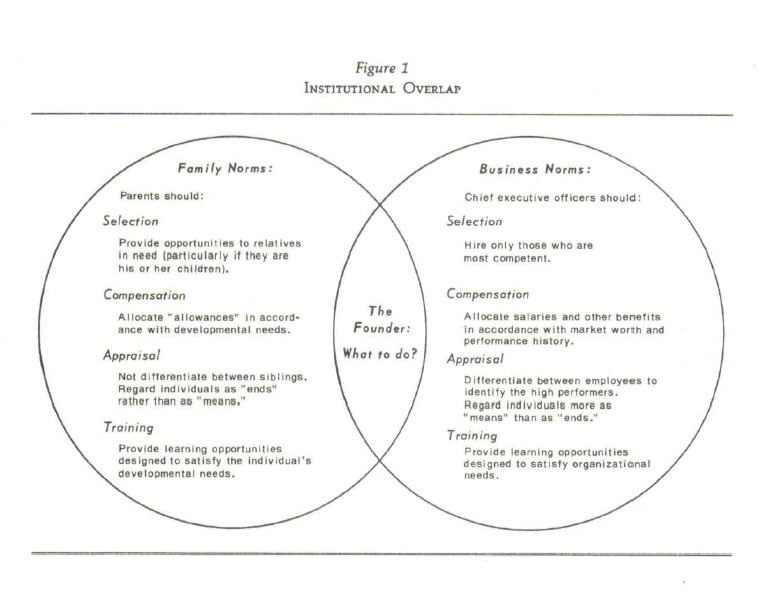

Each institution defines social relations in terms of a unique set of values, norms, and principles; each has its own distinct rules of conduct.

These institutional differences between family and business stem primarily from the fact that each exists in society for fundamentally different reasons. The family’s primary social function, on the one hand, is to assure the care and nurturance of its members. Thus social relations in the family are structured to satisfy family members’ various developmental needs. The fundamental raison d’etre of the business, on the other hand, is the generation of goods and services through organized to ask behavior. As a result, social relations in the firm are, on the whole, guided by norms and principles that facilitate the productive process.

In their formative years family firms often benefit from the overlap between family and business principles. During this stage, the firm’s social dynamics are still highly organic, with all employees reporting directly to the founder/entrepreneur. The informal nature of familial relations is frequently carried over into the firm, serving to foster commitment and a sense of identification with the founder’s dream. In addition, during these early days the family often provides the firm with a steady supply of trustworthy manpower.

As the business matures, however, and more complex organizational forms emerge, institutional overlap between family and firm begins to generate conflicts in the organization. Typically, these conflicts manifest themselves in the form of normative contradictions whereby what is expected from individuals in terms of family principles often violates what is expected from them according to business principles. (Gallo, 2004)

In most family firms, the person who experiences these institutional contradictions most strongly is the founder (usually the founder/ father), who sits at the head of both the family and the task systems. Typically the founder finds him- or herself operating under conditions of high normative ambiguity in which incongruent values, norms, and principles erode the ability to manage effectively.

Although these problems are structural in nature-that is, they result from conflicting social norms existing independently of the founder — he or she often experiences personal psychological difficulties as a result of the conflicting pressures. Founders frequently experience a great deal of stress from “internalizing” the contradictions that are built into their jobs as heads of the family firm.

Moreover, the psychological stress induced by this conflictive situation reduces the entrepreneur’s ability to manage effectively and sets the stage for the firm’s eventual downfall, which typically occurs about the time when the founder leaves the business. It is interesting to note that the average family firm exists for approximately 24 years, a period that happens to coincide with the average tenure of most founders.

Human Resources Problems

Contradictions between the norms and principles that operate in the family and those that operate in the business frequently interfere with the effective management of human resources in family firms. Let’s examine some characteristic ramifications of this institutional overlap.

Problems of Selection

Typically, relatives feel entitled to “claim their share” of the family business; they flock to the firm demanding jobs and opportunities regardless of their competence. The rationale rests on the family principle that unconditional help should always be granted to relatives who are in need. From a business standpoint, however, the founder knows that the firm cannot be allowed to become a welfare agency. The hiring of too many incompetent individuals (whether they are “family” or not) would certainly threaten the effectiveness and possibly even the survival of the business.

Founders often find themselves in the difficult situation of having to choose between either hiring and firing an incompetent relative or breaking up their relationship with some part of the family.

Problems of Compensation and Equity

In the area of compensation, remuneration of the relatives who work in the firm also creates difficult problems for the founder. The conflict here again is structural in nature and exists “independent of the founder’s will.” Let us examine some research findings that shed light on the dynamics underlying the giving and getting of rewards in the family and in the business.

Sociologists tell us that the norms and principles that regulate the process of giving and getting (that is, the exchange of goods and services) in the family are qualitatively different from the norms and principles that regulate the same process in the firm. The exchange of resources in the family is guided by implicit affective principles that focus each person’s attention on the needs, and long-term well-being of the other, rather than on the specific value of the goods and services being exchanged.

By contrast, the process of giving and getting that operates in the firm is regulated by economic principles that oblige individuals to be explicit about both the market value of the goods and services exchanged and the time frame within which the exchange will take place. Therefore, the notion arose of a fair day’s work for a fair day’s pay. Given the problems inherent in mixing the principles of exchange in family and business, it comes as no surprise that many founders have difficulty discussing terms of compensation with their relatives.

This is particularly the case with their children who work in the firm. As a result, compensation for relatives is often based on ambiguous principles deriving from a hybrid of family and business criteria and they generate all sorts of dysfunctional processes in the firm.

For instance, contrary to commonly held beliefs about nepotism, studies have shown that founders tend to under reward their relatives who work in the firm. While this practice is relatively harmless during the formative stages of the firm, it creates considerable problems in the mature family business.

Under rewarding relatives, regardless of their competence, may lead to a situation in which incompetent family employees are retained while competent family employees are driven to seek employment elsewhere. Founders repeatedly justify such under compensation by arguing that family members “have an obligation to help out” in the business. (Zahra, 2004) Moreover, founders frequently feel that rewarding relatives in terms of market rates would be perceived as favoritism by non family employees. Clearly, both of these rationales reflect some confusion about principles of exchange that should operate in the context of the firm.

In compensation, the problems created by the institutional overlap of family and business are not limited to incongruent principles of exchange. Perhaps one of the most difficult problems faced by the founder in this area stems from the fact that family and firm are regulated by different norms of fairness. In the context of the family, two dominant norms of fairness operate. In vertical family relationships—that is, the relationship between parents and their children — the dominant norm of fairness is the concept of need. Parents have a moral obligation to allocate their resources so that the children’s needs are met. In horizontal family relationships, such as the relationships among siblings, equality is the dominant fairness norm. Thus it is assumed that in allocations among siblings, each individual is entitled to an equal share of resources and opportunities.

However, the norm of fairness that operates in the firm is based on the concept of merit. Ideally, the level of rewards an employee receives is determined by his or her competence in accomplishing organizational goals. Given the fundamental task orientation of the business, it is more functional in this context to allocate resources so that those who are most productive receive proportionally larger shares of the resources available in the system.

The mixed nature of family business makes it difficult for founders to resolve allocation problems in a way consistent with both the norms of fairness that operate in the firm and the norms of fairness that operate in the family. The clash between the principles of fairness that operates in the family and in the firm lies at the heart of the problem of nepotism. Seen from the overlapping systems perspective, nepotism occurs when the ground rules that define fairness in the task system are violated – that is, when family are given rewards and privileges in the firm to which they are not entitled on the basis of merit and competence.

Problems in Appraisal

The institutional overlap between family and firm also interferes with the appraisal process. Frequently, founders experience many difficulties when trying to evaluate the performance of a close relative who works in the firm – particularly when it comes to objective evaluation of their own children. First of all, the very concept of appraisal (that is, objective assessment of an individual’s contribution and worth) in the context of a family system seems a preposterous idea. In a family system individuals are, by definition, seen as ends in themselves.

The standing of an individual in a family is determined more by who the individual “is” than by what the individual “does.” Applying a set of objectively derived criteria to evaluate a family member’s performance goes against the very principles that regulate and define social behavior in the family. (Chrisman, 2004) In the firm, on the other hand, the process of appraisal seems fully congruent with the requirements of a system whose primary function is economic productivity. In this context, looking at individuals more as means than as ends enables us to identify those who contribute most to the achievement of organizational goals.

It is not surprising; therefore, that a founder faced with having to assess the managerial competence of his or her own offspring experiences a great deal of stress because it is not possible simultaneously to do justice to the norms and prescriptions that operate in the family and in the business systems. Moreover, the founder’s difficulties in making such appraisals are frequently compounded by informational problems. These problems emerge when non family employees cover up a relative’s incompetence —either to curry favor or to avoid “crossing” the founder.

Problems in HR Training and Development

The clash between family and business principles also impacts the founder’s ability to effectively manage the training and development of family members. In this instance, founders frequently find it difficult to separate individual needs from organizational needs. From a family point of view, the relative’s training should focus on “whatever is best for him or her.” From a business point of view, training should emphasize learning experiences that will increase the individual’s ability to attain organizational goals. Very often, however, individual relatives’ needs do not coincide with the firm’s needs. Moreover, founders are frequently willing to invest organizational resources in ventures that, while being risky or even outright incompatible with the organization’s core mission, are intended to provide their offspring with an opportunity to grow and develop. (Anderson, 2003)

Coping Mechanisms

Caught in the midst of these conflicting institutional prescriptions, founders often have trouble adopting clear and explicit management criteria (Figure 1). According to Anderson, (2003), this is particularly true in those areas of human resources management in which family and business principles come directly into conflict. To cope with the stressful double bind in which they find themselves, many founders adopt one of two strategies.

One is to adopt decisions that compromise between conflicting family and business principles. These compromises, however, often lead to decisions that are suboptimal from a management point of view. For example, one founder who was unable to choose between his son and a professional manager as his successor decided to split the office of chief executive into two distinct offices, giving one to his son and one to the professional manager. In this case the founder’s “solution” led to a power struggle between the two that threatened the firm’s long-term survival.

Another coping strategy for dealing with the institutional contradictions that confront them is to indiscriminately oscillate between family and business principles. Founders often arbitrarily behave strictly in accordance with business principles in some instances and strictly in accordance with family principles in others, without laying down a set of criteria or guidelines that specify when family or business principles are appropriate. This constant oscillation between business and family principles often leads to discontent both among employees and among relatives, all of whom perceive the founder as being inconsistent and unpredictable in his or her managerial approach.

Solutions to These Problems

It is evident from the foregoing analysis that the institutional contradictions facing the founder are built into the very nature of these organizations, so the problems entailed can never be fully resolved as long as the firm remains a family business. From our perspective, the best that founders can hope for is to develop procedures for managing more constructively the contradictions inherent in their role as founders.

As an important first step toward the development of constructive coping strategies, founders need to gain the awareness that a fundamental part of the stress they experience is environmentally induced. Research evidence on what is typically referred to as “role conflict” suggests that understanding the problem’s structural roots would significantly reduce their stress and enhance their ability to manage these institutional contradictions more effectively.

Similarly, founders need to make significant others (both in the family and in the firm) aware of the contradictions that are built into the family firm’s structure. Shifting the problem’s source from the founder to the system would stimulate the formulation of procedures for separating family and business issues and would set the stage for collaborative problem solving among all the parties concerned.

The key to developing effective procedures for managing these contradictions is the separation of management and ownership. Basically, this entails examining the relatives who work in the firm from two distinct perspectives: an “ownership” perspective and a “management” perspective. From an ownership perspective, relatives would be subject to all the norms and principles that regulate family relations; from a management perspective, relatives would be affected by the firm’s principles. Let us briefly examine how this separation would work in terms of the various human resources problems discussed earlier.

First of all, the separation of ownership and management issues in terms of personnel selection would call for accepting into the firm only those relatives who, on business grounds, were thought to possess the skills needed to perform effectively on the job. Hence from a management perspective relatives would be treated just as others are treated when they apply for a position.

From an ownership point of view, on the other hand, relatives interested in working in the firm would be given the opportunity to acquire the necessary skills to meet the firm’s standards. These opportunities could take many forms, including sponsored apprenticeships in other firms, formal educational training, and so forth. The funds to cover the necessary training expenses would come from the family’s assets rather than from the business. In this way relatives could be taken care of in a manner consistent with family principles without necessarily compromising the firm’s sound management standards.

Second, in terms of the compensation process, a similar distinction between management and ownership needs to be made if we want to develop more constructive ways of managing the institutional overlap. In this case the separation of management and ownership would entail rewarding relatives working in the firm strictly on the basis of business principles. Any additional rewards, advantages, or opportunities for relatives would be allocated under the ownership umbrella quite independently from the relative’s standing in the firm. For instance, under these conditions a founder wishing to provide a son or daughter with an expensive life style would make the necessary income available to him or her by way of stock dividends, not by inflating the offspring’s salary beyond his or her professional worth in the market. Such an arrangement would ensure honoring the offspring’s privileges as an owner while maintaining an effective merit-based reward system.

Conflict Resolution in HR Practices

A unique feature of family business is its inherent multiple and interdependent roles, and examining a stress-based model of work conflict among owners across two nations in this context provides important insights into the interface between work and family. For example, members of family businesses are affected by an overlap of family, business, and ownership subsystems, with owners playing simultaneous roles among these three subsystems. These roles can be complementary, but they can also lead to confusion and create role conflict owing to differences in values between the family and business subsystems (Hollander and Bukowitz, 1990). Moreover, overlap between family and business can impede effective role performance and decision-making because of difficulties separating business decisions from family objectives.

Non- Family Owned Business and Hr Practices

Human resource management is somewhat different in the global environment that in the domestic environment. Several factors contribute to this. One factor is the differences in worldwide labor markets. Each country has a different min of workers, labor costs, and Non-family owned business firms. These business firms can choose the mix of human resources that is best for them. Another factor is differences in worker mobility. Various obstacles make it difficult or impossible to move workers form one country to another. These include physical, economic, legal, and cultural barriers.

Still another factor is managerial practices. Different business subcultures choose to manage their resources, including people, in different ways. The more the countries are in which a Non-family owned business firm operates, the greater the problem of conflicting managerial practices. Yet another factor is the difference between national and global orientations. Non-family owned business firms aspire toward global approaches. However, getting workers to set aside their national approaches is challenging. A final factor is control. Managing diverse people in faraway places is more difficult than managing employees at home.

Most Non-family owned business firms obtain unskilled and semiskilled workers in local markets unless the supply is inadequate. Locals or host- country nationals are natives of the country in which they work. For skilled, technical, and managerial workers, Non-family owned business firms have several options. They can sometimes hire these workers locally. In other cases, the Non-family owned business firms must choose expatriates. Expatriates are people who live and work outside their native courtiers. Expatriates from the country where the Non-family owned business firm for whom they work is headquartered are called parent- country national or home- county nationals. Expatriates form other countries are called third- country nationals.

Each Non-family owned business firm must balance the advantages and disadvantages of hiring each type of worker. Locals are usually culturally sensitive and easy to find, but they may not have the knowledge and skills needed by the foreign Non-family owned business firm./ Parent-country national often have the needed knowledge and skills and sometimes have the desired Non-family owned business firm orientation, but they often lack appropriate local language and cultural skills. Non-family owned business firms usually find parent- country nationals more costly to hire than other types of workers. Local laws could restrict employment of these nationals, too.

Third- country nationals could be more adaptable to local conditions than parent- country nationals. They may speak the local language and be able to make needed changes in culturally sensitive ways. In some cases, they could be more acceptable to locals than parent- country nationals. On the other hand, they may lack the desired Non-family owned business firm orientation. Regulations may make it difficult to hire them unless locals are unqualified. Selecting the best mix of employees from a variety of nationalities is challenging. Carrying out that mix in the global environment is even more challenging.

Human Resource Management Approaches in Global Business Scenario

A Non-family owned business firm’s approach to human resource to human resource management in the global environment is guided by its general Non-family owned business firm approach to human resource management. Most businesses in human resource management: ethnocentric, polycentric, regiocentric, or geocentric. The decision depends on several factors- such as governmental regulations and the Non-family owned business firm’s size, structure, strategy, attitudes, and staffing.

Ethnocentric Approach

The ethnocentric approach uses natives of the parent country of a business to fill key positions at home and abroad. This approach can by useful when new technology is being introduced into another country. It is also useful when prior experience is important. Sometimes less- developed countries ask that Non-family owned business firms transfer expertise and technology by using employees form the parent country to train and develop employees in the host country. The goal is to prepare the host country employees to manage the business.

The ethnocentric approach has drawbacks. For example, it deprives local workers of the opportunity to fill key managerial positions. This may lower the morale and lessen the productivity of local work3ers. Also, natives of the parent county might not be culturally sensitive enough to manage local workers well. These managers could make decisions that hurt the ability of the Non-family owned business firm to operate abroad.

Polycentric Approach

The polycentric approach uses natives of the host country of a business to manage operations within that country and natives of the parent country to manage at headquarters. In this situation, host country managers rarely advance to corporate headquarters since natives of the parent country are preferred by the Non-family owned business firm as managers at that level. This approach is advantageous since locals manage in the countries for which they are best prepared. It is also cheaper since locals, who require few, if any, incentives are readily available and generally less expensive to hire than others. The polycentric approach is helpful in politically sensitive situations because the managers are culturally sensitive locals, not foreigners. Further, the polycentric approach allows for continuity of management.

The polycentric approach has several disadvantages. One disadvantage is the cultural gap between the subsidiary managers and headquarters managers. If the gap is not bridged, then the subsidiaries any function too independently. Another disadvantage is limited opportunities for advancement. Natives of the host countries of the host countries can only advance within their subsidiaries and parent country natives can only advance within Non-family owned business firm headquarters. The result is that Non-family owned business firm decision makers at headquarters have little or no international experience. Nevertheless, their decisions have major effects on the subsidiaries.

Regiocentric Approach

The regiocentric approach uses manager’s form various countries within the geographic regions of a business. Although the mangers operate relatively independently in the region, they are not normally moved to the Non-family owned business firm headquarters. The regiocentric approach is adaptable to fit the Non-family owned business firm and product strategies. When regional expertise is needed, natives of the region are hired.

IF product knowledge is crucial, then parent- country nationals who heave ready access to corporate sources of information can be hired. One shortcoming of the regiocentric approach is that managers form the region may not understand the headquarters view. Also, corporate headquarters may not employ enough managers with international experience. This could result in poor decisions.

Geocentric Approach

The geocentric approach uses the best available a mangers for a business without regard for their country of origin. The geocentric Non-family owned business firm should have a worldwide strategy of business integration. The geocentric approach allows the development of international managers and reduces national biases. On the other hand, the geocentric approach has to deal with the fact that most governments want businesses to hire employees from the host countries. Getting approval for non-natives to work in some countries is difficult or impossible. Implementing the geocentric approach is expensive. It requires substantial training and employee development and more r5elocation costs. It also requires more centralization of human resource management and longer lead times before employees can be transferred because of the complexities of worldwide operation.

Determining Staffing Needs

A Non-family owned business firm must assess its staffing needs to compete successfully in the international market. Employment forecasting is estimating in advance the types and numbers of employees needed. Supply analysis is determining if there are sufficient types and numbers of employees available. Through selection or hiring and reduction or terminating processes, Non-family owned business firms balance the demand foe and supply of employees.

Once a Non-family owned business firm assesses its overall staffing needs, managers begin to fill individual jobs. A number of factors must be considered. When these types of questions are answered, specific job data are gathered. This includes information about such things as assigned tasks; performance standards; responsibilities; and knowledge, skill, and experience requirements. From this information a job description is prepared. A job description is a document that includes the job identification, job statement, job duties and responsibilities, and job specifications and requirements.

Recruiting Potential Employees

A Non-family owned business firm officially announces a job by circulating the job announcement and job description through appropriate channels. If the job will be filled by someone already working for the Non-family owned business firm, then internal channels will be used. The job information will be sent to all human resource offices within the Non-family owned business firm. Theses offices will post the information or notify Non-family owned business firm employees of the job availability in some other manner.

If the job will be filled by someone who currently does not work for the Non-family owned business firm, then different channels will be used. If a decision has been made to hire a parent- country national, then channels within the parent’s country will be selected. If a third- country national will be hired, then channels in other countries that could provide suitable employees will be used. Whereas, on the other hand, “It has been asserted that the concentration of shares in family management hands leads to a strong sense of mission, well-defined long-term goals, a capacity for self-analysis, and the ability to adapt to major changes without losing momentum (Moscetello, 1990 in Timothy, 1999).

The specific types of outlets selected could be influenced by the type of employee needed. If an unskilled or semiskilled worker is needed, then local public outlets such as Job Service orbits overseas equivalent might be used. If a skilled, technical, or managerial worker is needed, then public and private outlets might be used. For unusual or high- ranking managerial positions, the Non-family owned business firm might employ a specialized recruitment firm known as a headhunter. Such a firm, sometimes for a substantial fee, locates one or more qualifies applicants for the position.

Selecting Qualified Employees

Non-family owned business firms that operate in the global environment use a variety of methods to select the best applicant. The best applicant is the person with the highest potential to meet the job expectations. Most Non-family owned business firms use a combination of several selection methods, including careful examination of the applicant’s past accomplishments, relevant tests, and interviews. In the process of screening applicants, Non-family owned business firms are usually concerned about three broad factors. These are competence, adaptability, and personal characteristics.

The factor of competence relates to the ability to perform. Competence has a number for dimensions. One important dimension is technical knowledge. Is the applicant competent in the desired specialty areas? Another dimension is experience. Has the applicant performed similar or related tasks well in the past? For managerial positions, leadership and managerial ability are important. Can the applicant work with others to accomplish goals? For positions I other countries, cultural awareness and language skills are critical. Does the applicant understand the region or market for which he or she would be responsible? Is the applicant able to communicate fluently in the local language?

The factor of adaptability relates to the ability to adjust to different conditions. Possessing a serious interest in international business is necessary. Does the applicant really want to work abroad? The ability to relate to a wide variety of people is important, too. Does the applicant work effectively with diverse groups of people? The ability to empathize with others is needed. Can the applicant relate to the feelings, thoughts, and attitudes of those from other cultures? The appreciation of other managerial styles is also highly desirable. Can the applicant accept alternate managerial styles that are preferred by local?

The appreciation of various environmental constraints is needed, too. Does the applicant understand the dynamics of the complex environment in which international business is conducted? The ability of the applicant’s family to adjust to another location is particularly important for international assignments. Can the family members cope with the challenges of living abroad?

The factor for personal characteristics has many dimensions. The maturity of the employee is one dimension. Is the applicant mature enough, given the assignment and the culture in which the assignment will be undertaken? Another dimension is education. Does the applicant have a suitable educational level given the assignment and the location? In special circumstances gender is a concern. Will the applicant’s gender contribute toward or interfere with the ability to be successful in the working environment? In Saudi Arabia, for example, women are not business associates. The social acceptability of the applicant should also be considered.

Diplomacy is another trait to include. Is the applicant tactful in communication, especially when unpleasant information is involved? General health is another consideration. Is the applicant healthy enough to withstand the rigors of the work assignment? Mental stability and maturity should not be overlooked. Does the applicant function on an even keel and in a responsible manner? The stability of the relationships within the family is important, too. Will the family be able to withstand the additional challenges of a new job- perhaps abroad?

As various applicants are screened, one fact usually stands out: no single applicant possesses the perfect combination of competence, adaptability, and personal characteristics. When this happens, the Non-family owned business firm will have to balance the strengths of the various applicants against their weaknesses. Overall, which applicant best matches the needs of the position? Which applicant has the greatest likelihood of being successful o the job? THE answers to such question result in the selection of the best- qualified individual to fill the job.

Training and Development Are Critical

Employees make or break an international business, just as they do a domestic one. Their daily actions put the life of the Non-family owned business firm on the line. Consequently, Non-family owned business firms need to be sure all of their employees are well prepared for their work. This includes both lower- level and higher- level employees. Training and developing employees to work at their maximum potential are in the best interest of a Non-family owned business firm in the long run. Training and development are an investment in the future of the Non-family owned business firm. The better trained and developed the employees are, the greater the likelihood that the Non-family owned business firm will be successful.

Training and developing employees are major expenses for a Non-family owned business firm. Managers must decide what types of employees in which locations should receive specific types of training and development. These decisions are not easy. Because of limited resources, Non-family owned business firms have to balance needs and potential benefits. Comparing this, it can be said that “Family firms are also said to have a strategic advantage because their competitors do not have access to information about their operations or financial condition” (Johnson, 1990 in Timothy, 1999)

Historically speaking, many U.S. – based international Non-family owned business firms have skimped on training and development. This has contributed to their difficulties abroad. Many of their employees have not been well prepared to compete in the global marketplace. Non-family owned business firms headquartered in other countries often invest extensively in training and development. In fact, some countries have laws that require Non-family owned business firms to train and develop their employees. Such employees are often well prepared for work in the highly competitive global marketplace. U.S. based international Non-family owned business firms are now realizing the value of providing more extensive training and development.

Types of Training and Development

Managers working within international Non-family owned business firms need a variety of training and development. Managers need training in job- related issues. For example, they need to be aware of the current economic, legal, and political environments. They need to be current o relevant governmental policies and reputations. Managers also need to be aware of managerial practices within their areas of responsibility. Current information about the Non-family owned business firm, its subsidiaries, and their operations is needed, too. In addition, parent- country national and their families need training and development relating to relationships. At a minimum, they need to develop survival- skill knowledge in the local language upon arrival or shortly thereafter.

Special counseling may be needed if the manager has a working spouse. Increasingly, both husbands and wives work, and career moves that are beneficial to one may not be beneficial to the other. If only one of the two benefits, is eth job change worthwhile? Determining if the spouse can work into eh host country is important in many employment decisions. Some governments prohibit the spouses of foreign workers from being employed. What realistic employment options, if any, exist for the spouse in the host country if the spouse cannot work, can he or she adjust to that fact?

Providing training and development is costly. Nevertheless, Non-family owned business firms cannot fail to provide it especially for parent- country nationals. If parent- country nationals are unsuccessful abroad or if their families cannot adjust to like abroad, the Non-family owned business firm loses. In effect, a Non-family owned business firm that provides training and development is like a person who buys insurance: it helps to protect against the risks. Research suggests that relevant training and development does increase the likelihood of success abroad.

Training and Development Help to Prevent Failure

In spite of the efforts of many Non-family owned business firms to provide parent- county nationals with relevant training and development, a number of them are unsuccessful abroad. Theses employees may return home early, angry and frustrated. They may muddle through the assignment abroad with little or no success. They many even leave the Non-family owned business firm during or at the end of the overseas assignment. The associated monetary and psychological costs of failure are high. Failure hurts both the Non-family owned business firm and the employee.

One commonly cited reason is the inability of the employee to adjust to different physical and cultural environment. Another is the spouse’s inability to adjust to a different physical and cultural environment. Adjustment problems for other family members can also contribute toward failure. Characteristics of the employee’s personality can cause parent- country nationals to fail. For example, the person’s emotional maturity can be seriously strained by an overseas assignment. The person’s inability to work productively can contribute to failure. The parent- country national may not accept the new responsibilities.

He or she may lack the motivation to cope with the challenges of working abroad. She or he might even lack sufficient technical competence. To reduce the chances of failure abroad, Non-family owned business firms should select only successful and satisfied workers for overseas assignments. Non-family owned business firms should also provide extensive relevant training and development before departure, throughout the assignment abroad, and after returning home. Non-family owned business firms should make the international assignment part of the long- term employee development process. While, on the other side if compared, “Family firms have been said to make greater commitments to their missions, have more of a capacity for self-analysis, and less managerial politics” (Moscetello, 1990 in Timothy, 1999)

The international assignment should be accompanied with adequate communication between the non-family owned business firm and its employee. The Non-family owned business firm should know about the employee’s overseas experiences. The employee should know about changes at Non-family owned business firm headquarters, too. When the employee returns home, the Non-family owned business firm should provide a job that uses the employee’s international experience.

The knowledge and skills acquired abroad should not be ignored. Non-family owned business firm managers, especially those without international experience, should be trained to value international experience. The Non-family owned business firm should expect returning employees to experience reverse culture shock. (Reid, et. al. 1999)However, a supportive training and development program should minimize the readjustment time.

Motivating Employees Is Culturally Based

Managers around the world try to motivate their employees to perform to their fullest potential. While this ideal is commendable, the specific things that contribute to peak performance vary. What motivates a U.S. worker to perform well may have little or no effect elsewhere. Employee motivation is not universal. Instead, it is culturally based; that is, it varies from culture to culture. For example, the U.S. culture value individualism. It also values material possessions. It values taking personal risks to gain personal rewards. Consequently, for most U.S. workers motivation relates to the personal desire to assume risk in order to gain material rewards. Consequently, for most U.S. workers motivation relates to the personal desire to assume risk in order to gain material rewards.

For many in the U.S. money is a major motivator. It is a reward for accepting individual risks and performing well. The more personal responsibility a U.S. worker accepts and handles well, the more money he or she receives. The more money a U.S. worker ahs, the more material possessions she or he can acquire. Money motivates many in the U.S. to perform well. Of course, money is not the only motivator. As money allows U.S. workers to fulfill their needs and wants, money becomes less and less a motivator. The possibility of earning $3,000 more motivates a U.S. worker who earns the minimum wage. It will allow him or her to have more creature comforts. However, it does not motivate a U.S. millionaire very much. The millionaire has already used money to fulfill basic needs and wants.

Money cannot buy everything. Some desires must be fulfilled in other ways. Other factors, such as personal recognition and the sense of reaching full potential, motivate many.S. workers when money can no longer do so. Experiences worldwide suggest that U.S. models of motivation work best with U.S. workers in their native country. When U.S. – based international Non-family owned business firms try to apply their domestic models fail to explain motivation elsewhere because what motivates people differs from culture to culture.

For example, publicly praising the individual achievements of a U.S. worker may motivate him or her toward higher achievement. Treating a Japanese employee in the same manner may not motivate her or him. Since the Japanese employee in the same manner may not motivate her or him. Since the Japanese culture emphasizes group harmony, praising an individual may disrupt the group harmony. It can cause the person singled out to lose face or to suffer personal embarrassment. It can cause that person to behave in the future in a way that will not draw attention too himself or herself. In effect, praising a Japanese employee publicly can backfire. Consequently, international managers must use motivation strategies that are culturally acceptable to her employee. (Reid, et. al. 2002)

Compensating Employees

Employee compensation packages are influenced by the local culturally accepted standards. North American and European international Non-family owned business firms generally reward employees based on the type of work performed and the skills required. In places like Singapore and Hong Kong, individual performance and skill influence compensation. In Japan such factors as age, seniority, and group or Non-family owned business firm performance determine compensation. In Latin America penalties for forcing older employees into early retirement are so high that most Non-family owned business firms continue to pay these workers as much as younger workers. Since compensation standards vary around the world, Non-family owned business firms should be guided by local laws, employment practices, and employer obligations as they design compensation packages.

Employees of international Non-family owned business firms are motivated are motivated toward peak achievement by culturally sensitive compensation package. These benefit packages include both cash and non cash items. The mix of employee benefits varies from country to country; however, the cash component is typically the largest. Some Non-family owned business firms provide free or price- discounted products or services to their employees as non cash compensation.

As a contrast to this, “Personalized family-member involvement has led some to claim that family businesses are more creative (Pervin, 1997 in Timothy, 1999) and pay more attention to research and development” (Ward, 1997 in Timothy, 1999) In European countries such items as lunches and transportation are often part of non cash executive compensation. In less developed and developing countries, such basic foodstuffs as rice and flour are sometimes part of non cash benefits.

Anticipating Repatriation

Repatriation is the process a person goes through when returning home and getting settled after having worked abroad. The repatriation period often is a difficult one, filled with many adjustments. It is the challenging time when expatriates experience reverse culture shock. They have difficulty becoming reacquainted with their native culture. These major adjustments involve such things as work, finances, and social relationships.

Returning expatriates often experience a sense of isolation. They have grown in different detractions while abroad. Because their extended families and friends have not had similar experiences, they seem like strangers. To minimize the problems when returning home, expatriates need to plan ahead. It is not too early to start before ever leaving on an international assignment. With careful advanced planning, many of the problems of returning employees can be lessened. One should learn all about the host country and its way of life before going there. Once abroad, one must keep in frequent communication with former colleagues and friends. The expatriate should share new experiences with them and find out what is new in their lives.

In addition, one can learn to enjoy the benefits of the host culture and its way of life whenever possible. One should also begin exploring new career options at least one year before the end of the international assignment. The soon- to- be repatriate should encourage the current employer to find a suitable job that makes use of international experience. Also, one can explore options abroad and at home with other Non-family owned business firms. When returning home, the repatriate should be grateful for the adventures abroad. One can view one’s native culture in another light: appreciate it more than ever before, having experienced firsthand another way of life.

The goal of HRM is to assist organizations to meet their strategic goals by attracting and retaining qualified employees, and managing them effectively while ensuring that the organization complies with all appropriate labor laws. The field of human resources, formerly known as personnel, is currently in transition. In the past, HR was viewed as primarily an administrative function. That view is changing. The HR professional of today must understand the entire business, not just human resources. Today’s HR practitioners are becoming strategic business partners who act as consultants to senior management on the most effective use of an organizations’ #1 resource: its employees.

Models of personnel management have always been changing, and the title given to the management of people has been modified considerably over the years in response to changes in organizational structure. The metamorphosis of personnel to human resource management is a reflection of the contemporary view of employees as the company’s most valuable asset (Dobbins, Craig and Ehmke, Cole (2004). However, there are those who believe that HRM really isn’t any different to personnel management. HRM has been described as nothing more than “old wine in new bottles” (Gubman, E. (2004).

But even if the contents are the same, the ‘new label’ may help to give the personnel function a more contemporary image. Though unless there is also a new approach beyond the rhetoric that is concomitant with this updated title, the change of name will have little real effect (Jones, 1995)

Another view is that HRM is simply good personnel management (Litz, 1995) which succeeds by building upon its main shortcomings (McCollom, M.E. (1998). There are many basic similarities, but also obvious differences, between the two models (McCounaughy, D.L. and Phillips, G.M.1999). Human resource practice theories and models are philosophies, and maybe even discipline in their own right, where as personnel is a function.

The philosophy of personnel management is to take a “localized, problem-solving approach, directed principally at ‘workers'” (Gubman, E. (2004). In contrast to this HRM promotes a “more holistic orientation that embraces the management of all ’employees'” (Malone, S.C. (2002). HRM emphasizes the need to treat people as a key resource, and although this is not a new idea, there has been insufficient attention paid to it (Melin, L. and Nordqvist, 2000).

HRM is often distinguished from personnel management because of its strategic intent. HRM can be located at the strategic level because it involves the integration of HR and corporate strategies (Harvey, M. and Evans, R. (1995). As personnel management has become HRM, a change towards the integration of personnel functions has occurred. Whereas strategy was once the sole responsibility of line management, HR is becoming increasingly involved in developing and implementing the company’s strategic plan (Harvey, M. and Evans, R. (1994). With HRM adopting such an internally coherent approach to management, it has become recognized as a central business concern (Dobbins, Craig and Ehmke, Cole (2004).

Human resource planning (H.R.P.) plays an eminent role in any organization as a medium to achieve organizational goals through strategic human resource management. It is characterized by a systematic process, undertaken through forecasting human resource needs under changing conditions so that strategic planning is implemented to attain the right human resources needed in the future in accordance with their long term goals and objectives of the organization (Gubman, E. (2004).

The process of H.R.P. is intended to match projected human resources demand with its anticipated supply, with explicit consideration of the skills mix that will be necessary throughout the firm (Dunkley, J. (1997). Rather than a reactive and ad-hoc approach, H.R.P. apprehends a proactive slant whereby forecasts are made on labor surpluses or shortages using statistical or judgmental methods. Forecasting techniques are applied to certain areas within the organization so that further goals and strategic planning can be advocated (James, H.S. 1999).

Such goals and planning involve changes to HR activities hence human resource planning is not undertaken in isolation. Consequently it will generate issues attributed with various HR activities particularly employee learning (development), recruitment, performance management and retention, which will be further examined with specific reference to succession planning.

The importance of HR planning has generally been overlooked by organizations. Its proactive approach allows it to be more strategic in its decisions rather than face obstacles when unprepared. It can enhance the success of an organization through anticipation of labor shortages or surpluses and thus make decisions about the overall qualitative and quantitative balance of employees (Dobbins, Craig and Ehmke, Cole (2004). For instance, without a plan, a shortage in labor may instigate desperate measures to hire only good candidates and not the best. This will have cost and productivity implications not only in terms on money but also reputation, motivation etc. By implementing such plan, an organization can enhance its success and reduce various administrative costs by a third.

Few organizations implement this important process due to its time and cost implications, complexity, and inadequate support. More so, organizations often fall back on the notion that that H.R.P. is an isolated process but instead it requires integrated support with its strategic business plan along with its HR activities. Therefore HR personnel do not understand the H.R.P. process. Smith et al., (2004) alludes to the notion that there are inconsistencies with support between management along with hurdles resulting in strategies to be last priority and instead focus on short term goals. Instead, the adopted short term focus of daily resource tracking is more cost effective and simple requiring less management support as opposed to H.R.P.

H.R.P. is not a process in itself alone. Succession planning is one key planning area that is taken into account to identify and track high potential employees which are suitably qualified within the organization to compete for key managerial positions in the future (James, H.S. 2001) Succession planning is therefore a subset procedure of H.R.P. which aids an organization in attaining its HR goals because it constitutes one key area of strategic planning within H.R.P., which is training and development. The other three key areas of strategic H.R.P. include industrial relations, performance evaluation and reward systems, and staffing (Dunkley, J. (1997)