Introduction

Open innovation can be defined as the “use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge do accelerate internal innovation, and expand the markets for external use of innovation, respectively” (Chesbrough, 2006b). The provided definition suggests that open innovation is simpler than it actually is after digging a bit deeper into the subject. After all, open innovation is a paradigm change from closed to open innovation. A paradigm change by definition is a change in the underlying basic assumptions within the ruling theory of science in a specific field (Kuhn, 1970).

After analyzing the current innovation paradigm titled closed paradigm open innovation will be introduced on a conceptual level. Pointing out the differentiation factors between the two paradigms should lead to a better understanding of the consequences of the paradigm change.

The final section analyses the implications on the company and the ecosystem of an industry that arise from the new open innovation paradigm.

Open Innovation Concept

The present study concerns, as it has already been stated, investigating the tendencies of innovation dominant in the contemporary business reality and looking deeper into the tendency of change that may be witnessed in the shift of the innovation paradigm. With the help of thorough research it became possible to find out that the innovation strategies that used to be the sole task of the research and development department of any company undertaking the change became not the only ones applied in the sphere innovation. The changing needs and business environment dictated the necessity of a new approach which was found in the open exchange of achievements that are becoming the common heritage of the world business community and are being utilized nowadays with a different measure of success. The present chapter deals with the main concepts of the change taking place in the sphere of research, development, change and innovation nowadays – in this chapter the author investigates the both models that are currently in use – closed and open innovation, and investigates the leading factors for the emergence of the new model, as well as correlation of these two models.

Describing the new paradigm

Everything in the world is changing, and the way things are done is always affluent and dynamic. Evolution has always been the primary mover of survival – the human beings would still live in caves if they did not evolve and improve their conditions of living, tools of labor and physical status. Business is also a living organism that exists dynamically and fosters a huge amount of human and physical capital, gives work and sources for existence for millions of people all over the world. It is a new venture that is comparatively new – earlier people used to provide for their living with the help of physical labor, hunting and gardening etc. However, they would never succeed and survive if they did not invent some ways to improve their tools or methods of conducting the types of activities they did – in other way other neighbors would defeat them and take the majority of food to their families, consequently making other families starve. This simplistic example shows the necessity of constant improvement and innovation that people realized millions of years ago and that brought them to the present stage of their development.

Innovation is essential in every sphere of human activity, which is obvious for every businessman, be it an owner of a small private company or a huge multinational corporation. With the purpose of constant updating the resources, strategies and technologies of any company the research and development department has been created. Creative and motivated people have received the only task they had to be guided by – to find innovative methods of production, marketing etc. to win the competitive advantage as compared to other companies existing in the same segment of the market and to become financially successful and profit-making. The R&D department has always been considered to be a very prestigious place to work, and the job of an R&D manager has also been thought of as an elite position extremely hard to gain. The employees of this department bore the main responsibility for the success of the strategy of change and became the guiding force, taking all risks of failure or tremendous success on themselves. The research and set of decisions as well as solutions taken by this department was kept secret in order to protect the innovativeness of decision and to allow the company to surprise the customers, competitors and potential clients. This model may be roughly characterized as a controlled, inner process of conducting innovation, and it has been termed as a ‘closed innovation model’.

However, nowadays it is important to note the emerging tendency of open change – the utilization of widely accessible experience of other companies that previously conducted certain changes and succeeded in their undertaking. After the strategy has been implemented it becomes a worldwide heritage to which everyone may turn and the findings of which he or she may use. This way of conducting change has been termed as ‘open innovation model’, which has evolved as an equally efficient alternative to the closed change model.

In order to understand the open innovation phenomena it seems necessary to understand the closed innovation paradigm and the erosion factors: why this innovation paradigm became not the only one used and what benefits, advantages and improvements the open innovation model may bring to a company with a specific profile. Looking at the issue more fundamentally, it is also crucial to discuss the underlying shifts that enabled open innovation to be developed and gave it efficiency in implementation by the research and development managers seeking success for their companies.

The Closed Innovation Paradigm

The innovation paradigm was founded on a set of assumptions that were true for many years and specifically led to many breakthrough innovations after the World War II era (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xxi). Taking into consideration the Cold War influence and the common way of thinking after such a drastic shock to the world population, economy and well-being it goes without saying that the main principle of any activity in the sphere of business was strict control, guidance and surveillance. The natural outcome of such business philosophy was the closed innovation model, the main principle of which was control of all processes in the company, including innovation and improvement.

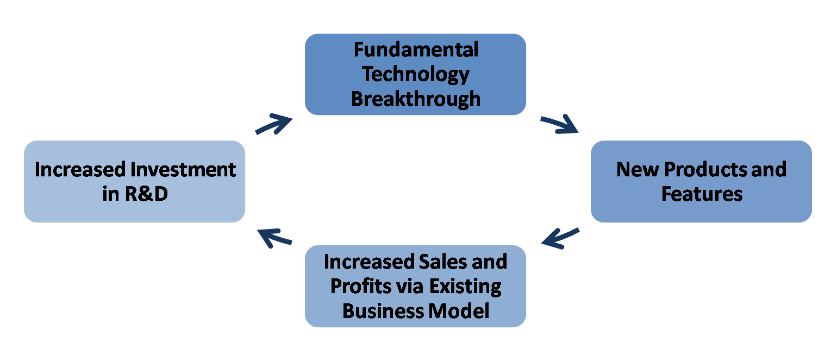

In the dominant paradigm of internal research and development the logic followed the virtuous cycle shown in Figure 1. Given that logic, fundamental technology breakthrough led to the production of new products and this advantage resulted in increased sales and profits with the existing business model. Those increased profits where then used to invest more resources in R&D in order to find the next technology breakthrough. It is obvious in the presently described and illustrated model that the development of innovation was isolated and circular, making the firm invest in itself and closing the circle of exchange on itself, thus making a span up at the spiral of improvement but spending too much more than it should have done if it took a more optimal approach. From this model it becomes evident that the company’s development and innovation are limited by the resources and potential of the company itself, which caused certain inconvenience and involved much more use of human resources (Herzog, 2008).

The model described also presupposes a certain model of construction of the R&D department that was the body responsible for innovation in the company. The understanding of innovation that follows the virtuous cycle of closed innovation (see Figure 1) led to heavily vertically integrated R&D departments within companies which in turn amplified an internally focused logic in understanding R&D(Chesbrough, 2003). This vertical integrated model was based on a set of assumptions. According to Chesbrough (2003, p. xx) the implicit rules of the closed innovation are the following:

- The best and brightest people in an industry have to be hired so that the smartest people work for the company in question (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xx).

- The only way to bring new products and services to market is discover and develop them inside the company (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xx).

- If a company makes a discovery first it will get the resulting product or service to market first and have the full first mover advantage (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xx).

- The company that brings an innovation to market first usually wins (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xx).

- If a company leads the industry in terms of R&D expenditure, this company will discover the most and best ideas and therefore become the market leader (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xx).

- Intellectual property is used to control the competition not to profit from the firm’s ideas and discoveries (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xx).

The enumerated principles of the closed innovation model in work imply that the company bears the overall responsibility for all stages of production, from the very beginning till the introduction of the product to the market, which increases time and expenditures enormously. Thus, following the idea of Philipp Herzog (2008), the process brings about the following consequences: first of all, the product planned for the innovation can enter the innovation process only at the very beginning; secondly, the innovation is put into practice with only the internal ideas, resources and competencies being involved; and, thirdly, can be commercialized only with the help of the firm’s own distribution resources (p. 19).

The result of the described considerations shows a completely another procedure of making innovation decisions as compared to the open innovation model. The products, ideas and projects generated with the help of the R&D department of one firm taking up the innovation go through the funnel process to reduce the number of alternatives that may be utilized by the firm itself, hence putting aside less promising or less successful ideas, or the projects that are beyond the potential of the firm. As a consequence of the funnel process, a huge number of ideas are neglected and stored inside the firm without any possibility for being implemented – with the purpose of securing the intellectual property or with the fear of gaining disadvantage with the competitors every company prefers not to publicize the results of the innovation process even if the company itself decided to drop those ideas for varied reasons. The innovation process yields productive results, but only for the preferred projects, while those left aside remain unused and are lost in the multitude of unsatisfactory opportunities that would be successfully utilized by other companies (Herzog, 2008).

The main two models of decision-making that were considered dominant in the course of the companies’ usage of the closed innovation model are the innovation funnel and the stage gate process – they both possess a certain number of peculiarities and are illustrated further.

Innovation Funnel in a Closed Innovation Paradigm

The innovation funnel has been currently used as a tool of the decision-making process in order to ensure consideration of a wide range of possible solutions and to investigate every possible alternative with the purpose of defining the best variant, integrating the positive features of the alternatives that have not won the tender and eliminating all possible drawbacks in the best variant that has been chosen, thus creating an integrated, improved and collective product or solution that would fit the demands of as many consumers as possible and would ensure the success of the company in the market. However, the closed model of innovation had certain peculiarities that resulted in certain specificity of the described model usage.

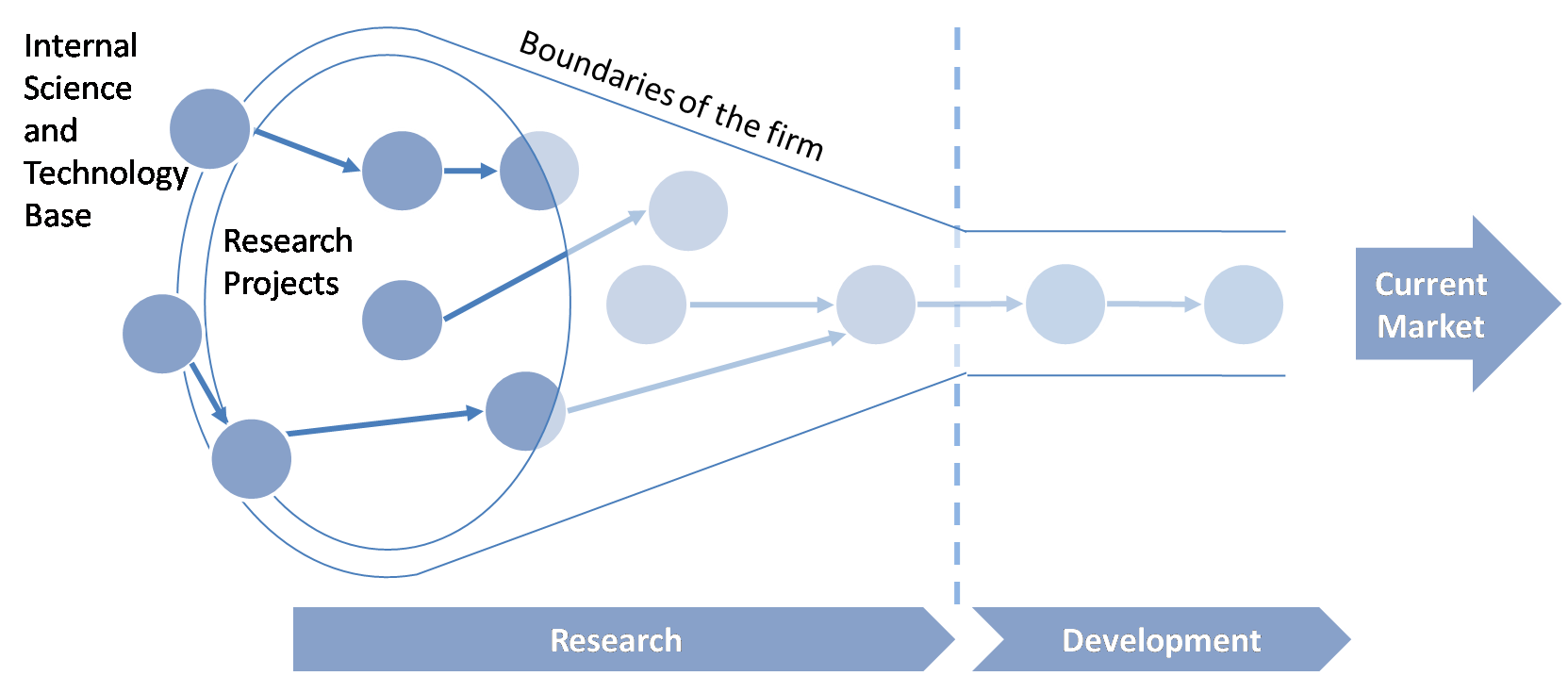

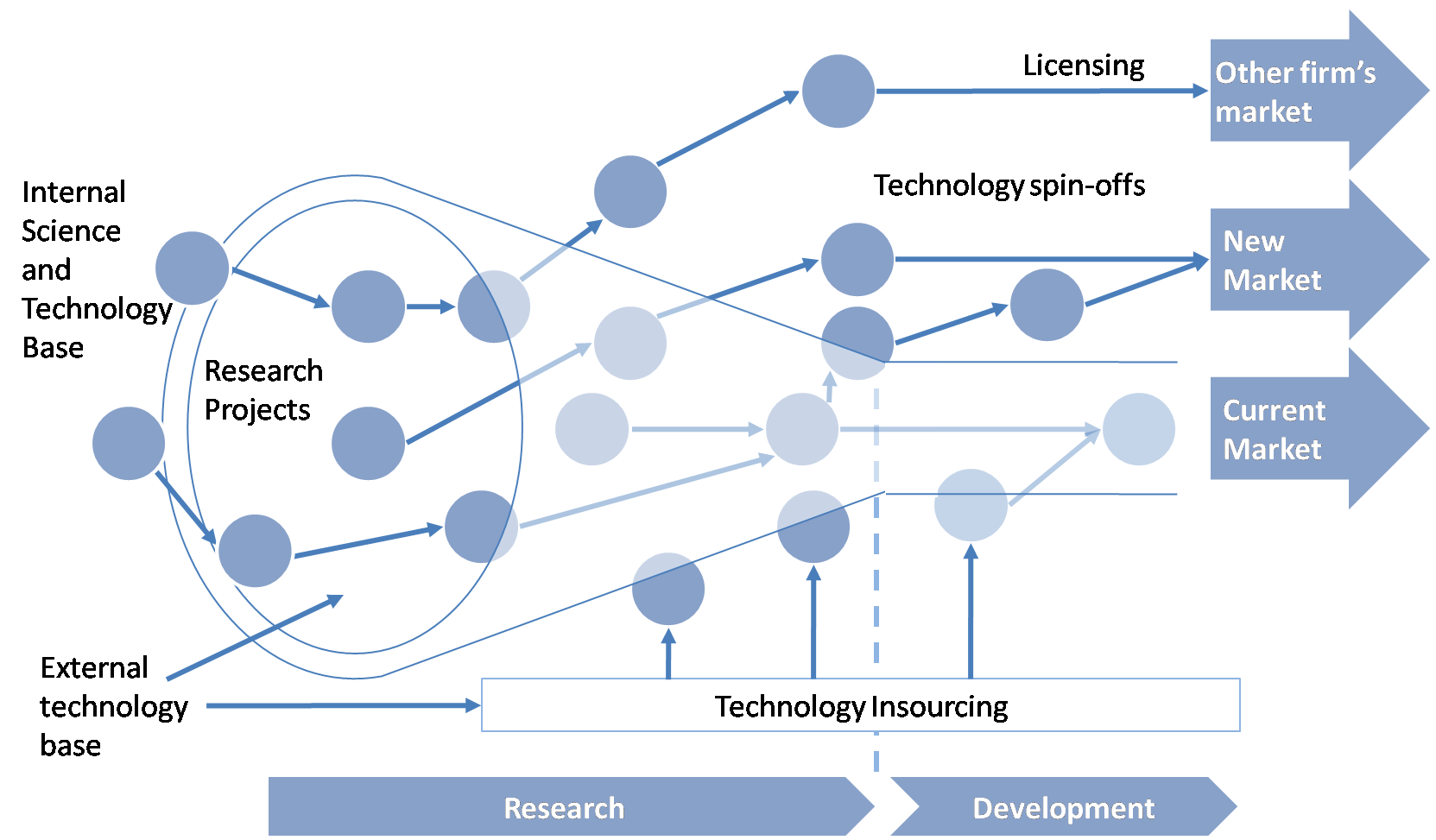

The list of logic underlying the implementation of the closed innovation model led to management of R&D and innovation that is mainly focused on eliminating as many false positives as possible (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xxii). False Positives in this sense are research projects or ideas which the company is working on but which do not result in new products or services the company sees potential to capitalize on in its current market with the current business model. Figure 2 illustrates the innovation funnel that follows the paradigm of closed innovation.

Out of an internal science and technology base research projects are started and pushed through the innovation funnel ending with new products or services for the customer. During this process, projects that do not fit the strategy are eliminated and the scarce internal research resources are allocated to more promising projects (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. xxi-xxii).

The only limitation that was already noted and that reduced the potential of the decision-making process currently described is the refusal to involve any ideas, people or expertise from outside the company, which made the decision isolated and deprived of diversity, freshness of understanding and objectivity of a glance of an outsider. It goes without saying that the considerations of closed innovation were mainly guided by the fear of competitors’ intelligence measures that would threaten the success of the planned innovation by means of utilizing the results of research and implementing them at earlier deadlines thus destroying the innovativeness of the strategy itself. However, engaging a limited number of ideas and a stable number of specialists would lead to the gradual outworking of the creative potential, the perception of researchers and developers becoming accommodated to the needs of the company thus reducing the creative potential and stagnating the generation of breakthrough ideas.

Stage Gate Process in a Closed Innovation Paradigm

Similar to the innovation funnel (Figure 2) the stage gate process is used to manage the innovation processes. This management principle also relies on the basic assumptions of a closed innovation paradigm.

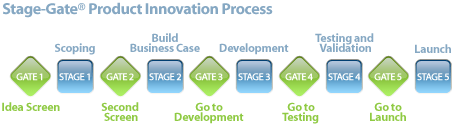

The main idea of the stage gate process is breaking the innovation process down into more manageable steps – into well-defined stages that are a series of activities. Every gate represents a decision point where, according to predefined measures, the project is moved forward or stopped. Secondly, the gates are used for allocating resources within the company to those projects that are the most promising (“Product Innovation Process,” 2008).

The Implications of the Closed Innovation Paradigm

The closed innovation paradigm worked very well throughout the 20th century and many breakthrough innovations are based on that paradigm (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xxi). According to Chesbrough (2003) the Bell Laboratories are a good example of a R&D department that had tremendous success following the closed innovation paradigm and discovered many physical phenomena which they were able to turn into many profitable products.

However, the focus of closed innovation lies on finding new products and services for the current market with the current business model (Chesbrough, 2006b). Moreover, the tools developed to manage R&D departments such as the stage gate process have their main advantages in resulting in an innovation process and in faster time of the product’s way to market, efficient resource allocation and not missing any critical point within the process because, if implemented correctly, those steps should be controlled in the gates (“Product Innovation Process,” 2008).

In the changing environment of the 21st century it is necessary to admit that the technology intensity is steadily increasing – in order to succeed and to be competitive in the growing and evolving world market every company has to keep pace with the development, research, innovation and change. With the help of the closed innovation model it was possible to generate high-quality and well-researched products; however, the period of time of slow business has passed away, and at the present moment businesses and enterprises have been put into conditions of tough competition. They have no time and ability to research and generate their own products following the traditional gating or funnel scheme as this will turn them into loss-making enterprises. High mobility of intellectual workers who are available on a short-term basis and who may bring innovation, fresh ideas and creativity to every single researched project – all this facilitated the use of open innovation model as well. For this reason open innovation may successfully help all firms gain their competitive advantage forces and enable them to survive in the changing and turbulent conditions of the world market.

Open Innovation

As it was stated earlier the closed innovation paradigm worked for many years and led to uncountable technological breakthroughs. However, during past few decades several factors combined and started to undermine the principles of the isolated use of the closed innovation paradigm. The need for a new approach was recognized, so taking into consideration the underlying principles of innovation as a process that should bring benefit and profit to the company through the production of a new concept (entering a new market, adopting a new technology or generating a new product) it was understood that the closed innovation model cannot be the only way to achieve the expected results. Since the change in the perception of change took place, the researchers as well as specialists from different spheres of business began looking for alternative ideas of the innovation process organization that would fit the needs of the business world. Open innovation was a newly found concept that took a deeply different approach to the process of production, thus promising profound changes in the process organization. It was conceptually different from the closed model process arrangement, so the main task at the present moment is to understand the way it approaches the change. The following chapter will be devoted to the reasons underlying the shift from the closed to the open innovation model and factors that brought about this change, making one model more preferable and usable than another one.

Undermining Factors in the logic of closed innovation

The following section addresses the changes that eventually led to the fact that some of the underlying factors of the closed innovation paradigm (see section 2.1) are not valid anymore and the realization of the fact that the application of closed innovation has already become not the only efficient variant of conducting the change in a company.

The first factor to be considered is the increased availability and mobility of skilled people. Whenever people leave a company they take a great deal of the knowledge with them and the new employer normally does not pay for that knowledge to the former company (Chesbrough, 2003, p. 34). In contrast, soccer clubs that have their own junior teams are paid for the effort of education of new and coming players by transfer fees. The fact that knowledge remains in the heads of the people however was true also in times when closed innovation worked well. The change that occurred in the context of the 21st century is the increased mobility of workers; it was traditional for many decades that employees were devoted to their companies and tried to retain their working places from the very beginning of their working age activity till its end, i.e. retirement. This work model is outdated today and it is the norm that people switch back and forth between companies and even industries (Aberdeen et al., 2007, p. 21). Furthermore, the knowledge of workers gets more important in general as society is moving towards a knowledge society leading to the fact that more and more knowledge is only stored in the heads of individuals rather than in procedures and methodologies (Naisbitt, 1984, p. 11) & (Aberdeen et al., 2007, p. 22).

The second factor is the increasing presence of venture capital firms that specialize in creation of new firms and commercialization of research activities. These start-ups, backed by the venture capitals knowledge of building firms, quickly became competitors for the large and established firms that used to be the only source of R&D in a given industry (Chesbrough, 2003, p. 37). However, this tendency does not seem to be that negative because the constant movement of ideas, inflow of creativity and alternative approaches to some traditional issues increases the potential of innovation and its chances for success because of its innovativeness and the intergated work of a number of minds with the purpose of creating a unified and successful product.

An additional, third factor can be found in the decreasing time to market many products and services which made it difficult for vertically integrated companies to leave innovations that do not fit the current market or business model lying on the shelf (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 4).

The forth factor can be seen in the increasing pressure on research departments within the large companies that was further increased by more knowledgeable and informed customers and suppliers. This high pace is only partly compatible with the do-it-all-yourself approach from the closed innovation paradigm (Chesbrough, 2003, p. 39).

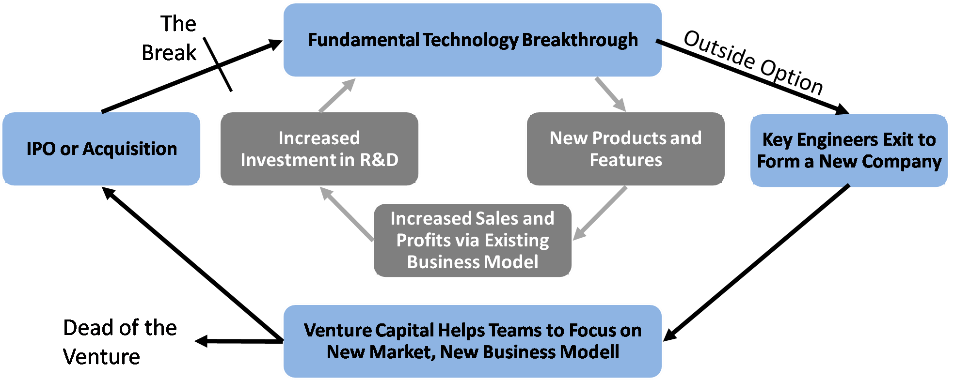

These four factors do not occur in all industries at the same time but it could have been observed that in those industries where the erosion factors are true, the virtuous cycle of the closed innovation paradigm (see Figure 1) does not work anymore (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xxiii). When a fundamental technology breakthrough was found within one of the research silos of a vertically integrated cathedral the researchers were well aware of an outside option to bring that innovation to market. When an innovation did not fit for the current market with the current business model it used to be shut down or put on the shelf. This is a direct result of the management of a stage gate or similar innovation process. For the reason there was no profit expected for the company concerning the innovation, it was put aside and neglected. Today, engineers or researchers have an option outside of the firm – something they lacked before (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. xxiii-xxiv). Unused ideas which the creators nevertheless consider worthy, profitable and potentially successful, can be taken to other firms and companies and be accepted there. Not all of created ventures of such kind have to be a success but if they are, a significant firm can rise out with the help of their start-up assistance and even obtain the potential to become a competitor.

More importantly, with the possibility of that outside path the company that originally financed the basic research does not profit from the innovation and cannot therefore use the money to reinvest it in its own research and development department. With the loss of the reinvestment possibility the closed innovation model is not sustainable anymore (Chesbrough, 2003, p. xxiv).

Figure 4 illustrates the virtuous cycle including the outside option that leaves to the break in the cycle because through an IPO or Acquisition the next fundamental technological breakthrough is not funded by the company that has profited from the profits the later innovation brought (Chesbrough, 2003). This option became understood by those intellectual workers who used to be employed in some companies and saw their ideas not used or neglected. The option brought about several benefits – the first one concerns the employee who ensures his intellectual and creative potential is realized and his idea is implemented into production, bringing him/her profit and working for the benefit of the company that agreed to accept it and risked to assess its profitability while another company refused to do that.

The second profit lies in the feedback of the company that agrees to utilize the idea that was not used by its competitor – the essence is that the idea is surely innovative, since it was rejected by another company, implying that the competitor took an initially different approach to the production of the present product. Another consideration is that the drawbacks seen in the rejected project and resulting in the refusal to generate it and implement it into production may come not from the evident disadvantage of the product, but from the lack of facilities in the competitor’s company to put the product into production or to market it. This way, it turns out that the project that was dropped by one company may be utilized by another one without any problems and, what is more, with even more success and profit that the competitor would have gained even if he/she implemented the production.

Thus, it is necessary to keep in mind the possible benefits that the open innovation model brings to companies implementing it in their everyday practice. The initial purpose of every innovation is to surprise the consumers, win the beneficial position in the market that will yield benefits for the company and for the customers. In this sphere it is notable that the closed innovation model outlived itself because of the failure to bring profits to the initial investors and to the breakage of the process of feedback to those who invest with the hope to gain profit from the company they rely on:

“The company that originally funded a breakthrough did not profit from the investment, and the firm that did reap the benefits did not reinvest its proceeds to finance the next generation of discoveries” (Chesbrough, 2003, p. 36).

This tendency undermined the principles of self-reliance in the process of innovation and initiated the new research in the sphere of innovation – it became clear that the firms themselves were unable to cope with the innovation process on their own without suffering considerable losses; more than that, the continuing tendency of losing the priority in investment and other firms’ gaining advantage from other companies’ effort made the manufacturing and business progress stagnate and seize developing, evolving in the way everybody wanted. The process of innovation seemed to be required as a dynamic, more or less autonomous and lively process in order to satisfy the changing needs of consumers and the ambitions of business people. This way the concept of open innovation emerged, becoming a productive alternative to the closed innovation model, complementing to it, but not substituting it fully however.

Looking at the two models in a comparative aspect, it is also relevant to recollect the opinion of Han van der Meer (2007) about the essence of some particular difference between open and closed innovation models:

“Inspecting the open innovation model closer, we can see mechanisms for importing and exporting knowledge, ideas and projects. Such mechanisms include methods, structures and systems in every stage of the innovation process that enable in- or outflow” (p. 196).

Van der Meer (2007) offers a set of solutions that become available with the help of the open innovation model, and classifies them according to their place in the business arrangement process. First of all, he indicates what the company may import and what may be beneficial for it, naming creative sessions networking with universities and scientific institutes, knowledge clusters ‘open day’, conferences, fairs and suppliers and end-users, and licensing in concerning the sphere of concepts. He continues with the sphere of development indicating such issues as patent search, partnering and spinning in. As for the business sphere, the author indicates venturing in as a profitable outcome of the open innovation model. Speaking about exporting, the author also gives out a number of spheres from which the enterprise may benefit: the sphere of concepts includes cluster projects, industry groups, and public-private cooperation as well as licensing out; development sector involves patent brokers and spinning out; business involves venturing out (van der Meer, 2007, p. 197).

So, as one can see, the benefits offered by the open innovation structure are enormous – the key issue only lies in the concepts of its correct usage in order to gain benefits and not only suffer losses. Open innovation creates a free space of business experience exchange in all possible spheres of activity in order to utilize unused ideas and enhance the current state of affairs in every particular company. However, the open innovation model is a much deeper concept than only open exchange of experience – it conceals a great set of implications, peculiarities and underwater stones that may infringe the rights and intellectual property of certain enterprises – the issue is that the verge between the open innovation exchange and the intellectual property violation is too vague because of the comparative novelty of the concept. These issues will be considered in the following chapters.

The Mouse case

One example that illustrates the shortcomings of the closed innovation model can be found in the first computer mouse. Originally the mouse was developed with the first graphical user interface for computers at the Palo Alto Research Centre (PARC), the cutting edge internal research lab from XEROX (Soojung-Kim Pang, 2002). But neither the graphical user interface nor the mouse as the input device that was needed in order to interact with the newly developed GUI was of much value to XEROX because they were looking for improvements in the printer and document management business (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. 4-12).

Rather it was an up and coming entrepreneur that saw the potential of the graphical user interface and the mouse to be used in personal computers. So Steve Jobs from Apple took up the idea he saw at the XEROX research facilities and further developed the GUI in order to be implemented in the first Macintosh and Lisa personal computers (Soojung-Kim Pang, 2002). The development of the mouse was outsourced to IDEO, a design company, which significantly reduced the complexity of the mouse and made it possible that the mouse could be produced for under 35$ – the original XEROX pointing device cost over 400$ to produce (Soojung-Kim Pang, 2002).

Even though XEROX has developed both breakthrough innovations in-house they did not profit from its commercialization.

The Open Innovation Paradigm

The open innovation paradigm is very complex and multi-faceted, thus making myriads of scholars and researchers look for the core sense of the concept that has been put into practice only lately. As defined by Joel West (2005), the open innovation paradigm represents the following concept:

“Open innovation reflects the ability of firms to profitably access external sources of innovations, and for the firms creating those external innovations to create a business model to capture the value from such innovations. Contrasted to the vertically integrated model, open innovation includes the use by firms of external sources of innovation and the ability of firms to monetize their innovations without having to build the complete solution themselves” (p. 2).

However, it is highly important to state why this model acquired popularity and became widely used as well as the closed innovation model. With the original virtuous cycle broken, the original model of knowledge monopolies of the established vertically integrated companies has come to an end. This paradigm change has led to rethinking of the underlying paradigm and led to generation of the term Open Innovation (Chesbrough, 2003c). According to the open innovation paradigm the internal R&D department still has value. But the internal forces of research are not seen as the only source of ideas and innovation. Ideas can as well be generated outside of the company’s research and development department and move inside the company’s development process (Chesbrough, 2003c, p. xxiv). Based on the same logic, the current market with the current business model is not the only possible way of profiting from an internally developed innovation. Other options are actively taken into consideration. One of the possibilities of marketing an innovation which does not fit in the development portfolio of the company in question is a start-up that is often staffed with the companies’ own research personnel but in this case is funded (fully or partly) by the company where the idea originates. In contrast to the closed innovation paradigm the leakage mechanism of a start-up is not seen as a cost of the research efforts but rather as a possibility to profit from an innovation that does not seem feasible with the current business model (Chesbrough, 2003c, p. xxiv).

Following the ideas of Chesbrough (2005) it is possible to give out a clear and over-grasping definition and understanding of the concept of the open innovation paradigm:

“Open innovation is a paradigm that assumes that firms can and should use external ideas as well as internal ideas, and internal and external paths to market, as they look to advance their technology. Open innovation processes combine internal and external ideas into architectures and systems. Open innovation processes utilize both external and internal ideas to create value, while defining internal mechanisms to claim some portion of that value. Open innovation assumes that internal ideas can also be taken to market through external channels, outside the current businesses of the firm, to generate additional value” (p. 2).

Additionally to the leakage path of a start-up, the company can also decide to license a discovery to another firm, assuring that the original expenses are covered with future revenues from that innovation. Figure 5 summarizes those different paths of research projects (Chesbrough, 2003c, p. xxv).

Compared to the closed innovation paradigm of managing R&D (see Figure 2), the open model not only acknowledges the in- and outflow of ideas but manages those flows actively.

One more aspect of the open innovation paradigm is its profitability recognized by a huge number of scholars concerning the assistance it may provide for the companies currently going through a period of radical innovation (RI) which takes a long period of time and can be hardly lived through even by large and stable companies (O’Connor, 2005). The underlying problem is that RI requires a long period of time and brings back profit only in about 10 years, which is highly unsatisfactory for the stakeholders and affects the consumers as well. Thus, the companies that have taken the risk to undertake radical innovation are led to a situation when the stakeholders withdraw their capital from the resources of the company, thus turning it bankrupt and destroying the core sense of the radical innovation, which appears to yield no results. In comparison with the closed innovation model, the open innovation may become helpful for the company going through a period of radical innovation through a set of characteristics that may save the company from bankruptcy and affect the period of radical change which the company has to overcome:

“Large established firms are seeking ways to develop RI competencies that can be sustained over time. The open innovation model offers firms an enormous help. If discoveries can be sourced from external parties as well as internal groups, and the innovation required to nurture those discoveries into business opportunities becomes more interactive with market and technology partners sooner, the lifecycle of RI can be sustainably shortened” (O’Connor, 2005, p. 4).

What makes Open Innovation Different

So far the focus of the paper was made on the factors that led to the paradigm change toward to open innovation one. If implemented in the research process of a company, a set of differentiation factors can be identified in contrast to the prior paradigm. These are the key factors that shape the new paradigm and constitute the major difference between the two discussed models. For this reason they need to be assessed in a particular way.

The role of external knowledge

In closed innovation, external knowledge only played a supplementary role. The firm was the primary source of knowledge and the internal knowledge creation was the focus of interest. The role model of using and creating internal knowledge was the Bell Laboratories (see 2.2) and many industrial R&D departments which were organized similarly. Even when companies started to take external knowledge into account, the balance between outside and inside knowledge was biased towards internal knowledge creation and usage (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 8).

For the open innovation paradigm the external knowledge that was not created from within the firm should have an equal standing as the internal knowledge (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 8).

External knowledge usage is the key characteristics of the novelty of the open innovation strategy, while it is the chief source of income, information, production variants, creativity and change. The internal R&D department is still involved in the process of innovation, but it bears less burden of knowledge generation – it is not responsible for the generation of ideas, which is the most time-consuming and significant stage. For this reason the external knowledge utilization becomes the central stage of the open innovation process. As it has been stated by Vanhaberveke and Cloodt (2005), “insourcing of externally developed technologies is crucial for the innovativeness of the company” (p. 2). These scholars also attribute major attention to the process of absorption of external knowledge, since there is nothing new that can be generated within the company with the help of its internal sources, or these new concepts will be limited and not fresh enough to satisfy the needs of the company for innovation.

Role of the business model

In the era of open innovation the R&D business model is at a central point of interest. In the closed paradigm world little attention was paid to the business model of innovating. The model used was more similar to securing the best and brightest people and if they are funded sufficiently they will come up with the best ideas possible (see 2.1) (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 8).

In open innovation companies actively seek good people in and outside the company to help to improve the business model. Additionally, in the open innovation model, the way to market is not restricted to the current business model of the company but the way through different channels (licensing or start-ups) is open and also desired (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 8).

In this point the remark of Vanhaverbeke and Cloodt (2005) from their article investigating agricultural biotechnology going through a period of open innovation also seems relevant in the context of the present discussion. When speaking about the new technologies interfering with the existing business model and the way of conducting business affairs, thus disrupting the production process, they state that “it is not the technology itself but the business model behind the application of that technology that gives it its disruptive power” (p. 11). This way, it becomes clear that the business model is a very influential element enacted in the process of the open innovation implementation, which plays a significant role in shaping the whole process, thus requiring separate attention.

Measurement Errors for evaluating R&D

Due to the fact that the focus in closed innovation attributed to innovation is laid on the existing business model, it is assumed that the evaluation of innovation projects does not have a systematic measurement error. If a R&D project is canceled it happens because the project does not fit the current business model and there is nothing to be done about it further on. The R&D processes are designed and managed in order to minimize Type I or false positive evaluation errors – meaning that a project goes through the firm’s process but fails in the market (see stage-gate process in section 2.1.2) (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 8). The possibility of Type II errors, where projects are stopped because they do not fit the current business model but still have value, is neglected (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 8). Statistical theory actually suggests that an elimination of Type I errors will increase the chance of Type II errors (“Type I and type II errors,” 2008).

In open innovation, the process of evaluating R&D projects is not only focused on project value within the current business model of the firm. In addition to the evaluation of whether a project fits the current strategy of the firm, an additional test in order to evaluate and identify if the project in question can create value in a potentially new market with a new business model has to be implemented (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 9). The core importance of this testing lies in the fact that the competitors also take risks when taking up the projects that were dropped by initial creators. The risk is in the potential attempt of the competitor to provide the company with a falsely profitable product, to make the company produce this product and then fail at the market. This technique may turn out to be useful if the company absorbing external knowledge relies on the advisor fully and does not continue testing the product. However, this is an extremely rare occasion, provided the competition in the contemporary business world is too tough and fierce to believe rivals. A second variant is more credible in the course of consideration of the issue – the company conducting certain research and deciding to establish additional testing with the purpose of eliminating errors of both types may be successful in leaving more projects inside the company (still bringing it more profit than in case of open innovation project exchange from which the company will then get only certain additional value and not full one) and eliminating a larger number of projects that prove to be potentially unsuccessful, leaving the challenge of implementing them to another company and sharing profits with it in case of its success.

Outbound flow of knowledge and technology

In closed innovation the outflow of knowledge and technology is not considered. In the open innovation paradigm knowledge and technology for which no clear path to market within the company can be identified have to be enabled to seek an outflow path externally (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 9).

The result of the outbound flow of knowledge was not fully positive, because the newly adopted innovation strategy led to such issues as licensing and intellectual property rights arising. Tim Simcoe (2005), basing his judgment on the ideas voiced by Chesbrough, states that the most problematic point in assessing the procedures of conducting open innovation processes lies in the fact that both closed and open standards may enable a wide range of companies to externally generate ideas for business, but the open method proves to generate more value:

“Open standards and open innovation both refer to a process that involves sharing and exchanging technology across firm boundaries. The difference is that the objective of open standard setting is to promote the adoption of a common standard, while the objective of open innovation is to profit from the commercialization of a new technology. In other words, open innovation might take place in a regime of either open or closed standards” (Simcoe, 2005, p. 9).

In open innovation the internal businesses have to take into consideration the external channels to market such as licensing, ventures and spin-offs as well. These channels have to be managed actively and taken into consideration as an alternative way of creating value for the firm (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 9). Nevertheless, it is still a slippery path which every firm is taking in order to increase its competitiveness and profitability, since there is always a threat of misinformation and distribution of false data that may hurt the company’s reputation or even make losses for it (Cooke, 2005, p. 12).

The underlying knowledge landscape

In closed innovation one of the underlying logic is that knowledge is scarce and hard to find. In open innovation it is believed that knowledge is widely distributed and generally useful. Therefore, also the best R&D departments have to be well connected to external sources of knowledge (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 9). Merck, a company that names itself a research-driven company, stated in the annual report 2000 that the internal resources are not enough to remain the leader in its field and that it is crucial for them to connect to the outside world:

“Merck accounts for about 1 percent of the biomedical research in the world. To tap into the remaining 99 percent, we must actively reach out to universities, research institutions and companies worldwide to bring the best of technology and potential products into Merck. The cascade of knowledge flowing from biotechnology and the unravelling of the human genome – to name only two recent developments – is far too complex for any one company to handle alone.” (“Merck Annual Report,” 2000)

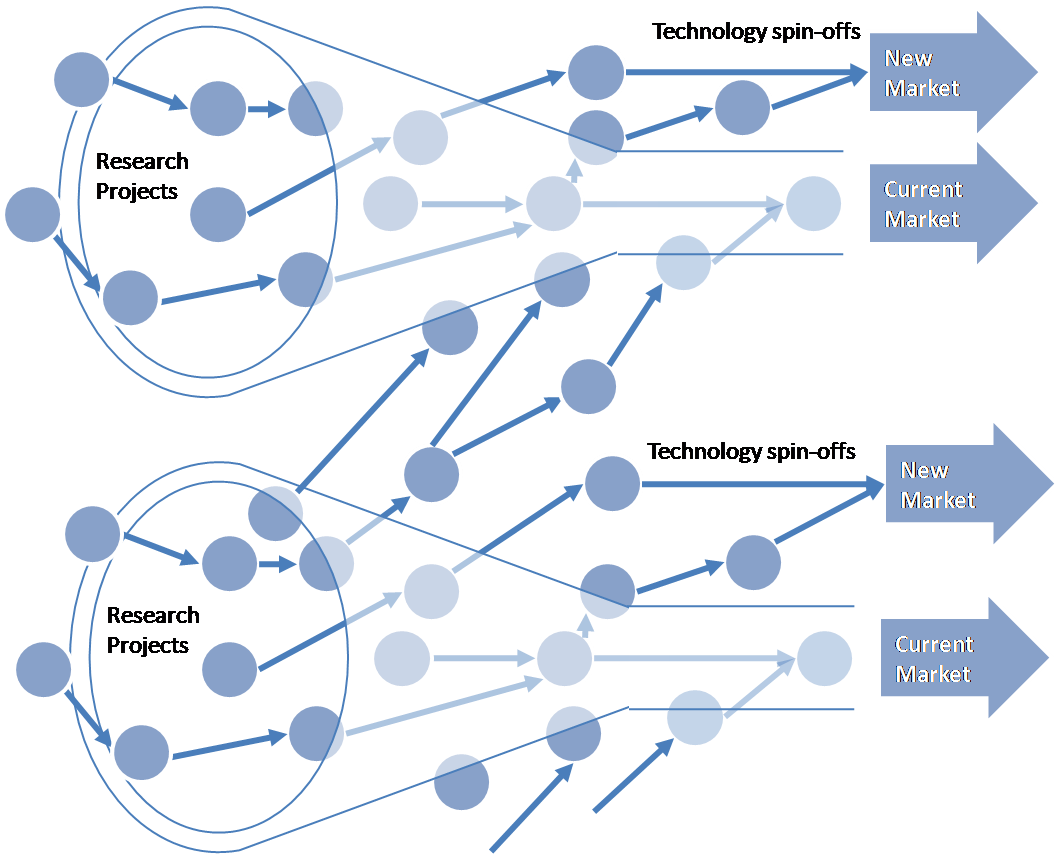

This openness of knowledge flow goes well beyond incorporating external sources in order to develop an innovation within the internal innovation process. In the knowledge landscape illustrated in Figure 6 knowledge flows almost freely in and out of companies (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. 43-44).

The in- and outflow of knowledge is restricted to not only two companies but within the complete ecosystem of an industry.

Role of IP management

Intellectual property management had the primary role of defending competition to free-ride on ideas created within a firm. The open innovation paradigm calls for a proactive use of IP management. In open innovation IP becomes a critical element of innovation, because according to the knowledge landscape (see Figure 6) knowledge and therefore also IP has to flow in and out of the company on a regular basis (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 10). This is how the situation should look like ideally; however, it often happens another way and the cases of unauthorized use of some other firms’ findings have become more and more frequent.

O’Mahony (2003) in his study of community based projects and the set of ways they use to protect their intellectual property rights has found out seven core methods of retaining proprietary appropriation:

- adopt software licenses with distribution terms that restrict proprietary appropriation;

- encourage compliance with licensing terms through normative and legal sanctions;

- incorporate to hold assets and protect individual contributors from liability;

- transfer individual property rights to collectively managed non-profit corporations;

- trademark the brands and logos designed to represent their work;

- assign trademarks to a foundation;

- actively protect the project’s brand (p. 1183).

Looking at the set of proposed solutions it becomes clear that nowadays there are a huge number of opportunities for firms to protect their private property rights and to save them from unauthorized use and application. Nonetheless, the set of licensing and protective rules does not provide full-scale protection; for this reason every company has to pay particular attention to the issues of security and non-violation of its rights.

Innovation Intermediaries

In open innovation, intermediaries start to play an important role. As the innovation process becomes more open, intermediate markets can arise in which parties can transact at stages that previously have been done completely inside the closed innovation process. When companies want or even need to exchange knowledge at an early phase of an innovation initiative, intermediaries can provide information, access or even financing to enable transactions to occur (Chesbrough, 2006b, p. 10).

The emergence of such organizations made the process of open information interchange much easier and securer, thus giving a chance for a new segment of the market to emerge, first of all, and further providing diverse assistance for the companies in assessment of their needs and allocating a set of resources to meet those needs. In general, involvement of intermediaries has become beneficial for the exporting and the importing companies because of their provision of systematized, professional help and protecting both participants of the open exchange process of the excessive participation of labor forces, excessive expenditures and time spent on the choice and arrangement of the open innovation process.

Metrics used to assess innovation capabilities

While R&D departments have been assessed based on principles that were true in the closed innovation, these measurements have to be adapted in order to assess the effectiveness of R&D departments that opened their innovation process. Chesbrough (2006b, p. 10) argues that questions like how much R&D is conducted within the firm’s value chain or what percentages of innovation activities originated outside of the firm, become more important. Another measure can aim at assessing the effectiveness of the different sources of innovation or profitability of the channels used to bring the innovation to market (start-up, licensing or own development). These measures will eventually substitute classical measures such as the percentage of sales spent on R&D, the percentage of sales that come from new products or how many patents were filed in the last year.

Summarization of the differentiation factors for Open Innovation

The following Table 1 summarizes the factors that differentiate open innovation from the closed innovation paradigm:

Table 1: Points of differentiation for Open Innovation7.

Thus, it is possible to sum up the facts that have been collected about the issues connected with both paradigms and to produce a set of relevant conclusions on the topic: first of all, it is necessary to remember about the importance of inflow and outflow of knowledge in the open innovation system, compared to the isolated knowledge circulation in the closed innovation model. Then, it is vital to estimate the importance of the business model in the context of which the open innovation process takes place. It is as well important to remember about the hidden challenges that have appeared with the emergency of open standards including violation of intellectual property rights, and to adopt a set of recommended policies to protect the intellectual knowledge of a particular firm. Intermediaries are the newly created segment of business activity that may help in the process of setting up an open innovation procedure. And, after all, the approach to assessing innovation process that is currently enacted also requires a change that was already illustrated in the works of Chesbrough.

Implications of Open Innovation

The preceding section described the closed innovation paradigm as the origin of the open innovation paradigm. Using the description of open innovation, the following sections will analyze the impact the open innovation will most likely have on business. The impact and implications for companies and management thereof can be structured on different levels. Starting with the most specific level, the implications on the R&D department will be derived from the above stated findings and differentiating factors. The second level is the company and its innovation strategy, followed by the implications on the ecosystem of an industry.

Impact on the R&D department

The role of the internal R&D department is not just canceled because of open innovation, but the role of the R&D department will change significantly. Rather than having the internal monopoly of research and creating new ideas, the research and development departments of companies that are managed according to the findings of the open innovation paradigm will have altered responsibilities. As the results of the study conducted by Michael Fritsch and Rolf Lukas (1999) show, it has been found out that the R&D department is highly important in every company and brings about only positive tendencies of its development:

“Firms that are engaged in R&D cooperation tend to be relatively large, have a comparatively high share of R&D employees, spend resources for monitoring external developments relevant to their innovation activities (‘Gatekeeper’) and are characterized by a relatively high aspiration level of their product innovation activities. Enterprises that maintain cooperative relationships with their suppliers tend to have a relatively low share of value added to turnover, indicating that this type of cooperation tends to be a substitute for internal R&D” (p. 14).

The new role will be to identify and connect the right ideas and research projects from outside and inside the company in order to identify the right projects that can create value. It will still be in the responsibility of the R&D department to scan and select the available technology and knowledge in order to create new products and services. However, the possible sources where ideas and knowledge can originate from have opened dramatically and more resources will be needed to fulfill the task that now appears crucial (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. 45-55).

Value creation will be less dependent on the deep understanding of one single technology that directly leads to a product or service. More likely, the most valuable innovations for the company will be created out of complex combinations of internal and external knowledge and different technologies. The underlying role of the R&D department is better described with the term knowledge brokering than the classical understanding of an R&D department (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. 45-55). Jens Christensen (2005) also indicates the changing role of the R&D department in the context of the open innovation and emphasizes its internationalization and decentralization (p.21).

Additionally, R&D’s responsibility will also be to identify the right and most profitable channels to bring an innovation to a market – the existing market, a new market within the current business model, a new market with a new business model (a venture) or licensing to other firms (Chesbrough, 2003, pp. 45-55).

The above stated has an important impact not only on the role of the R&D department in general but also on the individual roles of the personnel working in the department. The researchers and engineers will still be needed in order to conduct the research parts done internally. A number of new roles that are equally important have to be filled. Know-how on how to create a venture, and assessing the potential of a new innovation which is brought to the market on its own through a new created venture is now also needed internally. Additionally, the identification of new potential technologies and innovation needs a different set of skills than traditionally needed in the research field. Finding the right people to manage a more complex knowledge landscape will be crucial. Network abilities and broad understanding of many different fields of applications and technology in order to identify the missing pieces that will lead to market success of an innovation are important roles in the new R&D landscape.

Under such changing and challenging conditions there has appeared an alternative method of R&D management in the context of open innovation – it has been termed ‘corporate incubators’ and has been explicitly described by Becker and Gassman (2006). They authors distinguish four types thereof: fast-profit, market, leveraging and in-sourcing incubators. These specialized corporate units are meant for hatching new businesses by means of providing physical resources and support, and are mainly facilitated by the application of four basic types of knowledge: entrepreneurial, organizational, technological and complementary market knowledge. (Becker and Gassman, 2006). The incubator procedure has proved to be highly efficient in the process of decision-making in the R&D department due to its optimal segmentation encompassing all stages that are necessary to achieve the necessary result. The process includes four stages: selection, structuring, involvement and exit.

In order to proceed to the selection stage it is necessary to consider selection criteria – innovative projects, the proposed business plan and high growth potentials. Tenant origin is also one of the characteristics to be taken into account, including start-up and branches of existing companies. Industry focus is made on information and communication technology, services and financials as well as manufacturing. One more criterion is the ratio of enquiries to screening and admission – here such characteristics as high number of enquiries and high number of initial screening are required.

The next stage is structuring – here the relevant characteristics are equity ownership (should be about 20% but still is considered low) and service charges (the main attention is paid to internal charges, though a certain number of external charges is also taken into consideration). The involvement stage encompasses more characteristics that are relevant in the overall process. First of all, it is the involvement process (including no particular arrangements and little management time for advice), feedback to tenants (here the relevant points are information, periodical meetings and periodical surveys) and feedback to stakeholders (informal, periodical meetings).

The final stage is exit – it includes exit criteria (unachieved objectives, achieved objectives and limited space), reasons for which certain tenants leave (whether it is more room or end of the fixed period); and the assessment of the incubator performance (graduates, occupancy rate and financial performance) (Becker and Gassman, 2006). This method has repeatedly proved its efficiency and helps the R&D department accommodate to the changing environment of conducting its regular responsibilities under the conditions of the open innovation paradigm.

In order to be successful in open innovation the management principles of the R&D department will also have to change and adopt in order to manage the increased complexity the open innovation paradigm brings with it. The increased openness of the innovation process also creates an increased transparency of the innovation process and benchmarking possibilities with other companies. Additionally that leads to more competition between the internal R&D department and outside providers (Chesbrough, 2003).

Impact on the company and its innovation strategy

With the elimination of the simple understanding of R&D as a bunch of very smart people who, if funded sufficiently, will produce valuable outcome, the overall innovation strategy is more complicated to formulate. It will possibly need completely new tools to allocate budget to an R&D department in the open innovation. The first thing to be paid adequate attention to is the arrangement of innovation in a proper way, so that it would succeed and yield awaited results. With this purpose it is important, according to the opinion of Jan Bujis (2007), to create a proper pattern of leadership in order to satisfy the needs of the changing environment. The author considers such aspects of innovation as the content of innovation (whether it is the new product, the new technology or the new market), group dynamics of the innovation team, consideration of the innovation process as the creative process and the adequate construction of leadership, which is the key element in the point (Bujis, 2007, p. 1).

It is still important to attribute much attention to the human factor in the course of studying the change in the company’s strategic change – as it is witnessed from the case study of the company Endesa that successfully overcame the open innovation phase adopting the described model efficiently, “innovation cannot be created without the support of the organization’s employees. The aim is to take advantage of the organization’s internal knowledge as an essential resource” (Sanchez, 2007).

Moreover, companies within an open innovation are not forced to build up all their research abilities in-house. They also have a possibility to build their innovation strategy on an acquiring technique. With this approach the needed technology innovations are not built within the company and the internal R&D resources are minimal. The innovations are identified within technology ventures that do the research. This approach needs different skill sets within the organization. As an example of the innovative approach to the company’s structure in the process of open innovation one may consider the case described by Jacobides and Billiger (2006) in which the authors have been investigating change in the company Fashion Inc. for three years and assessed the changes that took place with their vertical integrated structure:

“By identifying the specific advantages resulting from a vertical architecture, we emphasize dynamic benefits. Appropriately designed boundaries allow firms to change and improve their own operations, strategic and productive capabilities, innovation potential, and resource allocation processes” (p. 258).

Identification and integration of ventures into a particular organization becomes dramatically more important than internal management of research and development projects. As noted by Chesbrough (2003a) in his work A Better Way to Innovate the 21st century dictates a really dramatic necessity for all companies to adopt the open innovation strategy, which is “accessing and exploiting outside knowledge while liberating their own internal expertise for others’ use” (p. 12).

Impact on the network of an ecosystem of an industry

Open Innovation is strongly linked to the concept of tying companies closer together with other companies. Companies are working more and more together in networks in order to create the greatest customer value (Vanhaverbeke, 2006, p. 205). Therefore innovation always has an important impact not only on the individual firm but also on the ecosystem or network the company operates in (Vanhaverbeke, 2006, p. 218). It has been identified as a general trend in management that companies specialize more on their core competency and break the value chain apart focusing only on those parts where a real competitive advantage can be gained (Aberdeen et al., 2007, p. 22). Due to the collapse of transaction costs, caused by the developments of information technology, the networking premises are more widely available today (Vanhaverbeke, 2006, p. 217) – not only for innovation but for doing business in general.

Continuing the point of discussion, it is necessary to mention the newly established concept of systemic innovation – it is the approach to open innovation that helps involve other participants and create an efficient network to reduce costs for different aspects of production processes:

“While integrating systemic innovation economizes on the cost of coordination and provides control benefits, it is frequently infeasible since even the largest firms lack the financial resources let alone technological and market capabilities to create the simultaneous complementary innovations necessary for the successful systemic innovation” (Maula et al., 2005, p. 7).

The network economy is another driver that can push the diffusion of open innovation even further. The reason for this is that in case companies are already connected to their suppliers, customers and sometimes competitors, the same network can also be partly used to foster the collaborative innovation processes.

The innovation network allows a different set of players to play an important part of a new product or service. The mixture of the involved partners depends on the goal the driving force behind an innovation wants to achieve. For example, a company can partner with universities or research facilities in order to explore the potential of a new technology (Vanhaverbeke, 2006). A company can also establish alliances with start-ups to learn from their technology or it can set up networks with suppliers and customers to launch new products or services together with the suppliers for the selected customers (Vanhaverbeke, 2006). In this respect it is relevant to recollect the results of the study of Christensen et al. (2005) in which the researchers made an attempt to look into the scheme of arranging the production networks and to investigate the ways in which they function successfully. The study was arranged on the sample of the transformation of consumer electronics in the context of the open innovation paradigm. The authors admit that from at the first glance the world market of electronics seems to be overfilled by products of a limited number of suppliers such as Sony, Panasonic, JVC etc. However, not everyone knows about the whole scope of companies involved in the overall supply chain of these companies, which is the innovation in itself –

“several other categories of firms that are mostly not associated with consumer electronics: small specialized suppliers of components and modules, broad-scoped electronic component providers, small providers of end-user products in the high-end markets, and the dedicated manufacturers and assemblers of components and systems” (Christensen et al., 2005, p. 1536).

This way it is seen that the practice of arranging large and extended conglomerates is widely spread – evidence for this may be found in practically every industry of the world business market nowadays. However, the impact open innovation has on the network and ecosystem in a given industry can only be guessed today, because collaborative learning and innovating is still a rather underexplored area in the field of network theories (Vanhaverbeke, 2006).

Cultural Change

Based on the impact that open innovation will have on companies and networks, probably the most important impact for management is the different culture needed. This is true not only for the company in question but also for all the participating companies or institutions – the 21st century has been marked by a changing paradigm of cultural implications in business as well as in the overall cross-cultural communication involved in the process of conducting business affairs (Chesbrough, 2003).

If one has a look at the organizational and individual changes needed in the R&D department, it seems obvious that there is a major shift needed to become a successful player in the open innovation. Management principles, skill sets of individuals and work incentives will have to undergo a radical change to accept innovations that originate outside the company or let innovations flow outside the own R&D. Thus, it is of crucial importance to estimate the key objectives of the change necessary to be undergone on the way to change and to implement open innovation successfully.

One of the biggest challenges after having understood the main driving forces of open innovation will be its successful adoption in companies and the cultural change will probably be one of the major hurdles in order to adapt to open innovation and profit from its advantages (Robbins and Judge, 2008).

In the context of discussing the cultural change it is important to turn to the work of Edgar Schein (1988) in which he defines the main concepts of culture relevant for the period of business change. First of all, he attracts the reader’s attention to the importance of perceiving the innovation in two major aspects – ‘content innovation’, i.e. the emergency of new products, new services, structures and strategies, and the ‘role innovation’, i.e. the way things are done and the new approaches to the distribution of roles in the production and management process. The primary attention in the preceding chapters was paid to the first aspect of the innovation, so this chapter is devoted to the second part of the issue – the deeply routed concepts that underlie the psychology of performing business tasks, the culture and tradition of conducting business affairs and the roles of leaders, managers and performers that are engaged in the overall process of production to make it innovative. The essence of the process is to make not only the outer change – in order for the change to work out it is essential that the inner change and perception of the personnel involved in the process would also evolve together with the enterprise. In order to define the ways to arrange this, it is necessary to consider the cultural implications relevant for the process.

First of all, one needs to define culture in order to facilitate further understanding of implications bound to this concept:

“Culture can be defined as the pattern of learned basic assumptions that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to the problems of survival and integration“ (Schein, 1988, p. 8).

Judging from this point, it is clear that culture is a set of moral and ethical principles that guide every person in his or her decision-making process while conducting business affairs. The way this set or code of rules and principles is arranged shapes the profile of the company and creates the company’s reputation, which is a trademark in itself. Thus, in order to create a correct set of rules that will help the personnel successfully adjust to the innovation process one has to understand the principles underlying the human perception of morale, virtue, correctness and propriety of certain activities etc. The organizational culture should be strong in order to become a firm basis for the company’s innovation. Edgar Schein (1988) outlines the following characteristics a culture should possess in order to follow the initial goal:

- the strengths of the initial convictions of the organizational founders;

- the stability of the group organization;

- the intensity of the learning experience in terms of number of crises survived and the emotional intensity of those shared crises;

- the degree to which the learning process has been one of anxiety avoidance rather than positive reinforcement (the more the culture serves to reduce anxiety, the more it will resist change (p. 9).

Judging from that point, it is possible to make certain implications about the inner structure of a particular organizational culture in order to assess the possibility of change within this organization. It has been long ago proved that the basic principles guiding the establishment of cultural values in a certain group are the underlying factor of success of innovation planned in this particular group. For this reason, to adequately assess the possibility of innovation change, it is first of all essential to take up the cultural change – the way people within the organization perceive innovation and the way they accept and promote it.

One more moment in defining the cultural change in an organization is defining what exactly is needed from an organizational profile in a company under the conditions of the open innovation paradigm. Menzel et al. (2006) have a firm opinion on this point:

“An appreciation of the importance of culture and cultural differences has high relevance for entrepreneurship and innovation. From an organization’s point of view, innovation activities are basically built around interaction processes between individuals and the surrounding organization, including the interaction and transfer of people across national, professional and corporate cultural boundaries” (p. 5).

According to the materials provided by Edgar Schein (1988) it is possible to estimate the level of fatalism in the personnel of the company – fatalistic companies are typically satisfied with the niche they occupy in the market and do not strive for success at all. They do not have any competitive spirit and are not used to innovation, thus being resistant to any introduced change. If the cultural situation in the company looks like that, the innovation measures are certain to fail and the personnel of the company itself will suppress any attempts for innovation (p. 17).

The second factor worth paying attention to is the level of cultural organization of the group constituting the personnel of the company – there are three types of group organization concerning innovation: proactive, reactive and harmonizing people (Schein, 1988, p. 18). The change is possible to be conducted only in a group of proactive people, because two other groups are likely to be highly resistant towards the change and will possibly create mechanisms for suppression of innovation inside the company.

The aspect of decision-making and the system of finding solutions is also relevant for the cultural change, as the change should concern all spheres of group activity. In this case Schein (1988) makes a hypothesis that the group work of which is strictly based on dogmas, traditions, rules and strict regulations are also not likely to be susceptible to innovation since they are too normalized in their activity in order to want anything else (p. 20). Change also requires time, and in order to produce the cultural change efficiently and achieve visible results one has to determine the period of time to implement the innovation plan. It is a common practice to divide the business time into certain periods, and an interesting peculiarity that has been revealed in the course of long-lasting studies is that the personnel of different levels of authority perceive time in different terms. Thus, it is important that the innovator should estimate the target audience to which he or she is going to address suggestions. The innovation plan may not be successful if the stipulated periods are handled in the wrong way – either wrong portions of time are used, or the wrong people are addressed.

Another important implication drawn by Schein (1988) lies within the scope of the group construction – he states that the innovative cultural change also depends on whether there are innovative people in the senior management of the company. If there are some people who may implement the change, then the innovation is more likely to succeed. However, if there are no people in the administration who would assist the change then even the prevalence of people in the staff seeking innovation may fail to promote the change within the company (p. 26-27).

Schein (1988) sees the main key to success in the innovation process in the promotion of cultural diversity and involvement of active participation in the process of representatives of different cultures which, nevertheless, have to be authoritative enough for their opinion to be respected and taken into consideration seriously within the organization. The author sees the way out in the multinational organizations that have subsidiaries in several countries – by promoting cultural exchange between the subsidiaries and the parent organization the change is likely to be more successful and prompt, yielding much better results.

From everything that has been said one can make an inference that the cultural change is possible only under the condition of systematic, well-organized change of the implications for the managerial staff and for the regular personnel taking into consideration all aspects of group characteristics and group dynamics in a particular company. One specific trait of every individual comprising a group should be paid even more attention to, distinguishing itself in the whole set of characteristics mentioned in the list – it is creativity that pushes the progress of innovation ahead, so it has to be encouraged in all possible ways in order to achieve the change in cultural standards and guidance of a particular company. As noted by Teresa M. Amabile (1997),

“Creativity is the first step in innovation, which is the successful implementation of those novele, appropriate ideas. And innovation is absolutely vital for long-term corporate success. Because the business world is seldom static, and because the pace of change appears to be rapidly accelerating, no firm that continues to deliver the same products and services in the same way can long survive” (p. 40).

The Case of DSM

In the context of discussing the cultural change implications it is relevant to have a precise look at the experience of the DSM company, the organization that proved to be successful in expanding their business, creating additional opportunities and sustaining its competitive advantage in the world market in its segment of life sciences and performance materials with the help of adapting to the conditions of open innovation. The case is explicitly described in the work of Kirschbaum (2005).

First of all, the company claimed to adopt the strategy of ‘culture of change’ with the purpose of creating value – what is significant, the choice of culture as the underlying principle of gaining profit was rather innovative for that time. They also realized that venturing is important in the process of achieving growth, so they adopted an innovative policy of gating – the way they established new subsidiaries that had to pass a certain number of gates, being closed in case they did not prove to be competitive at any of the gating stages, or continuing their existence in case they remained profitable and promising for the paternal business (Kirschbaum, 2005, p. 26).

In addition to the newly established method of expansion, the DSM Company worked out a set of inner incentives for the employees involved in the process of production. They called this new type of mindset ‘intrapreneurship’, thus implying that the person engaged in the working process of DSM has to be fully dedicated and committed to the company and to the job he or she does. The concept of intrapreneurship comprised a set of rules and characteristics that had to be observed in order to correspond to the stipulated image of the worker, e.g. the person had to be ready to do any job necessary for his or her project to work out; he or she should be true to the stipulated goals, but realistic on how to achieve them; recruiting a strong working team has become an essential factor of success; the person had to forget the pride and to be able to work in a team, sharing credits and benefits wherever it was necessary; the initiative was highly encouraged as intrapreneurs were welcome to ask for forgiveness rather than for permission (Kirschbaum, 2005, p. 27).