Introduction

The corporate world is characterised by disruptive change that requires organisations to produce value. With competition, organisations aim at producing greater value as compared to their competitors by combining innovation, quality, and efficiency to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. Nevertheless, organisations cannot acquire sustainable competitive advantage in the absence of organisational learning. Apart from enhancing the people’s performance by promoting interpersonal communication and encoding an organisation’s routines, organisational learning influences adaptations, thus promoting diversity. The main objective of this paper is to evaluate the contribution of organisational learning to the contemporary understanding of workplace practices.

Definition: Organisational Learning

Organisational learning entails an interdisciplinary field that integrates economics, sociology, and psychological concepts in the study of workplace practices (OLW Week 01-Lacture 2015). Gherardi (2001) adds to this argument by highlighting that organisational learning motivates an organisation’s employees to learn. In the course of learning, employees use new information and knowledge to the advantage of the firm. However, organisational learning cannot be effective if it fails to instil new insights in addition to influencing behavioural and action change. According to Lyles and Schwenk (1992), a strategic manager focuses on changing strategic behaviour to influence performance within an organisation. As the top management teams focus on expanding an organisation’s shared vision, they ensure that they extend organisational knowledge to employees.

At this point, one may question whether learning is a behavioural as well as a cognitive process. According to the theorists who subscribe to the cognitive perspective, learning contributes to the development of new insights. For example, from new knowledge, employees can form informed decisions and interpretations of a situation, thus leading to creativity and innovativeness. However, for organisational learning to occur, new knowledge must be beneficial to the organisation, and be used for the intended purposes. From this explanation, learning entails the acquisition of new knowledge by which learners develop cognitive maps and new beliefs. However, change portrayed in the course of learning may not be behavioural. However, Lyles and Schwenks (1992) posit that for learning to be considered as organisational, it must be aimed at influencing positive change. Organisational change begins at the individual level, as it is the responsibility of employees and the management to change an organisation. At the individual level, learning influences the employees’ cognitions to the extent that they develop new beliefs or change their behaviour to facilitate the formation of informed decisions. With reference to the theory of behavioural learning, organisational learning aims at increasing potential behaviour amongst employees by equipping them with information (Brown & Duguid 1991). After an organisation’s units acquire new knowledge, they use it to the benefit of the company by distributing the knowledge or expanding the organisation’s actions (Brown & Duguid 1991).

Contributions of organisational learning

Enhancing group performance

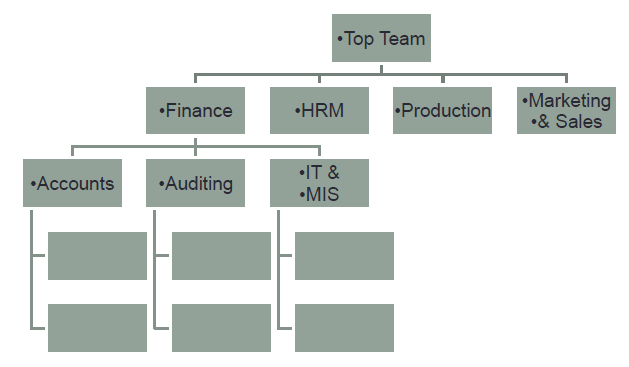

In the modern times, corporate culture advocates the implementation of organisational structures that depict clear definition of power and control. Power and control define hierarchy in organisations as command and communication flow from the top management to the subordinate employees. For example, figure I below illustrates typical power and command flow in an organisation. From the chart, one can deduce that the top team is in charge of the entire organisation. However, the team works with the departmental heads charged with coordinating teams within their departments. For example, in this illustration, the head of the finance department is changed with coordinating accountants and auditors among other teams working in the finance department (OLW Week 02-Lecture 2015)

Although corporate power and authority contribute to bureaucracies, it is the responsibility of the management to empower their subordinates. By equipping employees with the right skills, organisations are assured of being competitive in the market place. For creativity and innovativeness to prevail in a firm, the management must eliminate bureaucratic structures. The elimination of bureaucratic structures enhances performance among employees (OLW Week 02-Lecture 2015). With the elimination of bureaucracies, it is crucial for the management to encourage teamwork for effective completion of projects.

According to Weick and Karlene (1993), organisations can hardly achieve operational reliability in the absence of collective thinking. For example, in organisations dealing with aircraft services and flight operations, individualism contributes to an increment in the rate of organisational errors. Owing to the delicate nature of such operations, high levels of accuracy are encouraged such as strategy calls for the continuous operational reliability for the organisation to improve or maintain its performance. In such organisations, the overall performance depends on the quality of services offered by employees. Such a situation requires teamwork for the organisation to develop and maintain efficiency and reliability. In the course of working as a team, team members abandon individualism and embrace collective thinking. With group cognition, team members can hardly work without consulting one another. Furthermore, members become careful with their actions because an individual’s mistake affects the performance of the team and the entire organisation. Such high level of interdependence among the team members contributes to the creation of reliable and smart systems within an organisation (Weick & Karlene 1993).

However, a group’s performance depends on the level of interrelation amongst activities undertaken by the members. Mutually shared fields ensure that team members extend their ideas to other members, thus strengthening social forces among themselves. From this analysis, it is evident that group phenomenon encompasses the product and conditions of individuals’ actions in the course of production. In the absence of social forces among team members, a team cannot achieve its purpose due to the lack of direction as an organising centre. In some industries such as flight operations, collective mind influences performance crucially. For example, the team working in the air department is responsible for monitoring and dispatching information to both incoming and outgoing aircrafts. However, they have to work with landing signal officers and air operations controllers who monitor and instruct aircrafts. Nevertheless, air operations personnel act on integrated information that influences the current and future behaviour. Although members of air operations team may be working independently, the integration of their information at some point is crucial as it influences the ultimate results.

From this illustration, one can conclude that team members act independently in executing their individual roles. However, the results of their actions must reflect collective thinking by representing the team’s joint actions. Envisaging interdependence among team members highlights the team’s solidity and the members’ ability to bring into existence facts that enhance an organisation’s reliability and efficiency (Weick & Karlene 1993). In addition, this illustration depicts various aspects of behavioural view of power and authority in relation to influence. Power and authority account for the rules, force, procedures, and exchange magnetism among the team members. In the course of working as a group or team, the top management has to set rules and procedures by which members abide in the course of executing the project. Rules and procedures bar members from interfering with other people’s roles, hence restoring sanity in the organisation. Moreover, through power the top management team develops and maintains group cohesion amongst different teams (OLW Week 02-Lecture 2015).

Enhancing employee development

Brown and Duguid (1991) posit that the employees’ mode of organising their work differ from ways and descriptions documented by the organisation. Differences in the workplace practices require training of employees in an attempt to improve work practices. Nevertheless, deviating from the conventional descriptions depicts innovativeness among employees. As part of change, employees follow procedures that they perceive to be effective, as long as they target the organisation’s goals and objectives (Brown & Duguid 1991).

As Weick and Karlene (1993) state, modern organisations prefer teamwork to working as an individual. With the differences in actual practices among employees, it may be difficult to evaluate and manage performance among team members owing to their differences. In a bid to improve team performance, organisations focus on reassessing their work, learning, and innovations to establish connections among the members. Such an attempt pushes an organisation to train employees and equip them with adequate technology to enhance work comprehension while detaching from the formal description (Brown & Duguid 1991). Learning entails a bridge between innovations and working. In the course of learning, an employee acquires new knowledge that influences him or her to change his or her way of perceiving situations and interpreting such perceptions. In the end, changes in perceptions contribute to changes of the communities in which work occurs. Furthermore, such changes pave a way for innovativeness and creativity among employees (Brown & Duguid 1991)

According to Swan, Scarbrough, and Robertson (2002), spontaneous creativity and innovativeness cannot occur in the absence of communities of practice. However, it is the responsibility of the management to build, align, and support these communities for the organisation to grow and expand in terms of generating new ideas and processes. In some circumstance, organisations may expose their employees to knowledge and learn through training, but fail to enhance the learning experience. Under such a circumstance, a community of practice helps employees to acquire the necessary learning experience, despite the organisational constraints that affect innovativeness and creativity. From this analysis, it is easy to conclude that the researchers depict communities of practice as an activity system that motivates employees to understand their contributions to both the community and the organisation. Such communities unite employees by providing them with a platform on which to share different ideas to enhance individual and group growth and development (Swan, Scarbrough & Robertson 2002).

Researchers also recognise that although organisational learning integrates qualitative research, it addresses how organisations can innovate and gain competitive advantage over the competitors. Successful product innovation is crucial to an organisation’s success. However, the level of innovativeness depends on how appropriate employees can combine manufacturing coupled with technical and marketing strategies to facilitate a new product’s success (OLW Week 09-Lecture 2015). With reference to the OLW Week 02-Lecture (2015), corporate power and authority contribute to bureaucracy. Bureaucracy constrains learning and innovativeness among employees. Such an argument reveals some of the organisational constraints that impede creativity and innovativeness among employees. The elimination of formal boundaries within corporate structures promotes the sharing of responsibilities amongst an organisation’s groups, hence promoting delegation of duties and authority (OLW Week 09-Lecture 2015). Apart from implementing cultural strategies, adopting the model of community of practice entails an effective way of improving innovation practices within an organisation (OLW Week 09-Lecture 2015).

In contrast to the network approach, the community of practice approach promotes tight ties among members by providing a central node from which they obtain guidance. Furthermore, the community exposes employees to formal and tacit knowledge on which members base their ideas (OLW Week 09-Lecture 2015). With reference to figure 2, it is evident that a community of practice is solid, as opposed to the networks in which the level of interdependence is quite low. In a community, few innovators and experts occupy the top level, but they ensure that information flows to members in the lower levels.

According to Swan, Scarbrough and Robertson (2002), a community of practice not only eliminates bureaucratic barriers, but also promotes positive learning and knowledge flow among the members. However, knowledge flow is limited within the community and it can hardly flow across other communities. Such a move bars radical innovations across groups and the wider organisation. Nevertheless, the communities can be exploited to the advantage of the organisation.

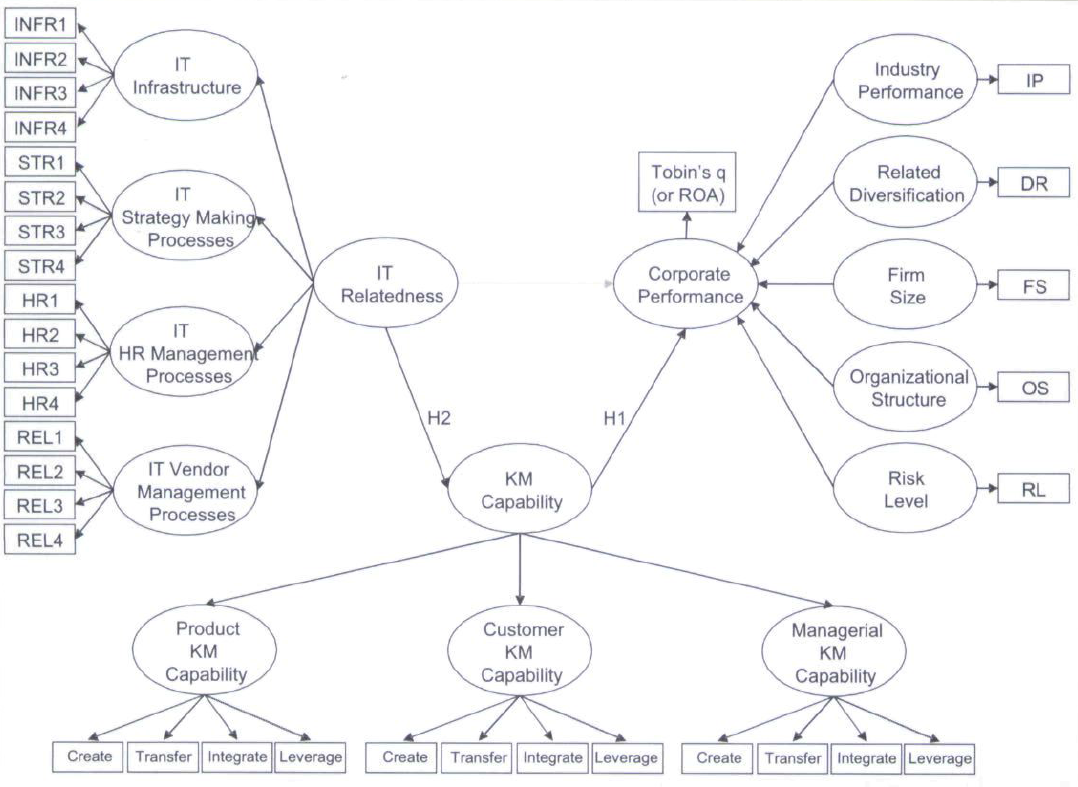

In the course of learning in a community of practice, members acquire knowledge and information that is beneficial to the organisation. However, the inability to allow information flow across different communities within an organisation entails a constraining factor that limits innovativeness at the organisational level. However, the management can overcome this challenge by implementing adequate strategies to enhance knowledge management at the individual level. According to Tanriverdi (2005), an organisation’s performance comprises the integration of a variety of factors that influence performance in one way or another. Tanriverdi (2005) further reveals knowledge management as a critical factor aimed at linking information technology and an organisation’s performance. In the course of enhancing knowledge management, organisations should ensure the implementation of measures to enhance an efficient exchange of information among employees, irrespective of the community of practice in which they belong (Tanriverdi 2005). For example, firms can encourage departmental rotation expose employees to different communities of practice. Interactions among employees from different communities enhance the exchange of ideas and information, thus stimulating creativity and innovativeness at the organisational level. Such rotations are possible as it is the responsibility of the top management in consultation with the departmental heads to initiate permanent or temporary reshuffles within a firm (Swan, Scarbrough & Robertson 2002).

Tanriverdi (2005) posits that with the help of information technology, multi-business firms can create across-unit synergy for efficient management of knowledge. Given that firms possess large pools of knowledge resources, failure to manage that knowledge effectively contributes to poor performance across an organisation’s units. Proper utilisation of information technology facilitates adequate management of an organisation’s knowledge in addition to facilitating adequate utilisation of cross-unit knowledge synergies.

Cross-unit knowledge synergies can be equated to sharing knowledge across different communities of practice in an organisation. Although such information hardly flows from one unit to the other, it is possible to facilitate the flow across interrelated processes with the help of technology (Tanriverdi 2005). Through technology, an organisation can create, transfer, integrate, and leverage information across different units as highlighted in figure 3.

Cross-unit coordination of information can be hectic, especially when using human-intensive mechanisms. Furthermore, human mechanisms are costly to maintain and limited in their processing and coordination capabilities (Tanriverdi 2005). However, IT-based mechanisms are not subject to such limitations, thus ensuring continuous processing and coordination of information across an organisation’s units. Such a move contributes to IT mechanisms having greatest influence on an organisation’s productivity. However, it is the management’s role to ensure that the organisation has adequate and appropriate information technology infrastructures for the IT-based mechanisms to succeed (Tanriverdi 2005).

Conclusion

Organisational learning contributes to the contemporary understanding of workplace practices significantly. In organisational learning, employees gain knowledge and use it to the advantage of the organisation. Novel knowledge expands an organisation’s actions and performance by fostering innovativeness and creativity. In the course of enhancing innovativeness, organisations eliminate barriers such as bureaucratic procedures and promote group cognition to promote teamwork within the organisation. Furthermore, organisational learning contributes to the employees’ development in the long term. As the organisation aims at benefiting from new knowledge acquired by the workforce, employees also experience career growth and development due to the exposure to training and workshops. The majority of the large organisations are exposed to large sources of information. The lack of proper information processing and coordination leads to poor performance. At this point, researchers recommend the use of IT-based mechanisms to ensure effective flow of information across an organisation’s units.

Reference

Brown, J & Duguid, B 1991, ‘Organisational learning and communities-of-practice: toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation’, Organisational Science, vo. 2, no. 1, pp. 40-57

Gherardi, S 2001, ‘From organisational learning to practice-based knowing’, Human Relations vol. 54, no. 131, pp.131-139.

Lyles, M & Schwenk, R 1992, ‘Top management, strategy and organisational knowledge structures’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 29, no. 2, pp.55-174.

OLW Week 01-Lecture, 2015, Organisational Learning in the Workplace.

OLW Week 02-Lecture, 2015, Traditional learning theory.

OLW Week 09-Lecture, 2015, Innovation-as-practice: understanding the nature practice.

Swan, J, Scarbrough, H & Robertson, M 2002, ‘The construction of communities of practice in the management of innovation’, Management Learning, vol. 33, no. 4, pp. 477-496.

Tanriverdi, H 2005, ‘Information technology relatedness, knowledge management capability, and performance of multi-business firms’, MIS Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 311-334.

Weick, K & Karlene, R 1993, ‘Collective mind in organisations: heedful interrelating on’, Administrative Science Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 3, pp.357-381.