Introduction

Islamic banking (ISB) is very unique due to the legal concepts it contains, which are based on the Islamic faith. This banking system adheres to Sharia law and is implemented in many Islamic states across the globe. The three pillars of Islamic banking are Aqeedah (faith), Sharia (laws regulating activities and banking platforms) and Akhlaq (defining banking institutions’ behaviour toward customers, such as interest rate regimes) (Schaechter, 2003). The proposed single currency regime should be implemented if the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) hopes to create a competitive economic bloc within the Middle East to challenge the dominance of the European Union (EU) and other Western economic blocs. Although the idea has been circulating for over three decades, several challenges have made it difficult to meet the 2010 adoption deadline (Alesina and Barro, 2002). There is a need to determine the direct impact of adopting a single currency regime on the ISB within the GCC as an economic bloc. Chapter 1 comprises the present study’s research background, problem statement, hypothesis, aims and objectives, questions and significance.

Research Background

The GCC was established in 1981 by six states (Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates [UAE]) when they felt the need to establish a competitive conglomerate of states in the form of an economic bloc (Darratand Al Shamsi, 2005). The initial agreement was signed in Abu Dhabi with the primary intention of formulating common regulations within the fields of finance, administration and legislation. The GCC agreement included a pact on joint ventures, united military arsenals and the establishment of a unitary currency (the Gulf Dinar) to foster cooperation and ties among the citizens of the six states (Nakibullah, 2011). Although the single currency regime is still in the pipeline, two member states, Oman and the UAE, pulled out of the arrangement.

The other four states, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, are on track to adopt the regime (Laabas and Limam, 2002). These four members have agreed to link the proposed currency to the United States Dollar (USD) due to varying inflation rates within the member states. Despite some progress within the GCC, the proposed single currency has met with mixed reactions due to the complexity of its implementation and competing interests among the member states (Dellas and Tavlas, 2009). Some of the challenges include disagreements about the most inclusive common central bank and market and how to give the member states the maximum amount of influence within the international financial system (Nakibullah, 2011). Although the Monetary Council has made progress in addressing this, one current concern has been the potential impact of the Gulf Dinar on the Sharia-based ISB that is currently operating within the member states (Espinoza, Prasad and Williams, 2010).

Economic integration has become a fundamental instrument for creating strategic financial markets, such as the ISB in the GCC. Islamic banking follows Sharia law (Dellas and Tavlas, 2009), and creating a single currency regime is likely to make Islamic banking more attractive and flexible to the needs of each economy operating within the bloc. For instance, a single currency regime may result in reduced capital costs due to low and standardised interest rates across the member states, stimulating the financial sector via an increase indirect investment, as was the case in the EU model (with the exception of Greece) (Darrat and Al Shamsi, 2005). The other benefits of a single currency regime include an expanded financial market, an increased flow of capital and an environment that is ideal for stable and consistent trade, especially if it is properly integrated into the dynamic banking sector (Buiter, 2008).

Adopting a single currency regime within the GCC bloc was meant to integrate the member states into an economic unit– a process that began over three decades ago (Beaver, 2011). There is a need to investigate the correlation between adopting a single currency regime within Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain and the ISB within the GCC in order to determine its potential to foster a competitive economic bloc. Specifically, there is a need to examine the impact of the Gulf Dinar on the ISB within the banking industry for the four member states that have agreed to pursue a unitary currency. Within the conventional banking system in Europe, adopting a single currency (Euro) has resulted in increased capital flow and expanded markets, except in Greece, where capital flow has shown a downward trend (Laabas and Limam, 2002). However, no research has been done on the potential impact of a single currency on the unique ISB, which includes Sharia, faith and morals, especially when more than one state has an agreement about integrating themselves into an economic bloc. Thus, the present study analyses issues surrounding the introduction of the Gulf Dinar into the ISBs currently in use by the GCC member states of Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain and its potential to promote a sustainable financial system in the GCC bloc (Blank, 2011).

Research Problem Statement

The introduction of the Gulf Dinar to the GCC economic bloc is currently facing the challenge of competing interests, as the financial markets within each member state are overshadowing the realisation of a single currency regime (Dellas and Tavlas, 2009). For instance, Oman and the UAE requested more time to prepare their economies and financial markets to operate within the proposed single currency (Espinoza, Prasad and Williams, 2010). The four states that have agreed to adopt the single currency have different regulations within their individual ISBs. Moreover, levels of inflation in the financial markets in Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain are different (Laabas and Limam, 2002). This means that integrating a single currency in the GCC within the banking industry is also a technical issue (Nakibullah, 2011). For example, although all of the member states have banking systems that function within Sharia law, there are institutional challenges in terms of accounting regulations in each state (Darrat and Al Shamsi, 2005). Within Bahrain’s banking sector, accounting institutions focus on market forces and government mechanisms when making financial agreements. In Kuwait, the government plays a more proactive role in regulating the ISB (Callen et al., 2016). It would be very difficult for these two economies to merge due to the differences in their current systems and currencies (Filip and Raffournier, 2010). Therefore, this study explores strategies that the GCC bloc could use to ensure that the proposed single currency regime addresses the above challenges and properly integrate a uniform ISB within the six GCC states.

Research Hypothesis

This study focuses on an economic policy that has not been implemented–that is, the introduction of a single currency within Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain to foster a GCC economic bloc. Thus, it makes the primary assumption that there are both positive and negative impacts within the unitary banking system. Its hypothesis is based on the above assumption and was derived as follows:

- Null hypothesis: The adoption of a single currency has an impact on the Islamic banking industry within the integrated GCC bloc.

- Alternate hypothesis: The adoption of a single currency does not have an impact on the Islamic banking industry within the integrated GCC bloc.

Research Aims and Objectives

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the potential impacts of adopting a single currency regime in Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain on the ISB that has been proposed as part of the GCC integration agreement. The study focuses on the banking industry with the assumption that the financial institutions within Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain will operate under one ISB model. The objectives of the paper revolve around the probable impacts of the Gulf Dinar on the unitary ISB in the GCC. To achieve the above aim, the following objectives were created:

- To determine the impact of a single currency regime on Islamic banking accounting practices within the four member states of the GCC before adopting the Gulf Dinar.

- To determine the impact of a single currency regime on the GCC banking industry’s accounting practices after adopting a single currency regime.

- To determine the impact of a post-single currency Islamic banking accounting policy model on the integration of the GCC member states into a single economic bloc.

Research Questions

The following research questions were based on the research objectives:

- What are the potential impacts of a single currency regime on the ISB?

- What are the potential impacts of a post-single currency ISB on the integration of the GCC member states into a single economic bloc?

Significance of the Study

The banking industry within the GCC was selected because the adoption of a single currency will directly affect its functionality, especially when the GCC member states implement a unitary banking system. Since banks within the GCC use the ISB, there is a need to establish the relationship between the Sharia-based banking model and a single currency regime, especially when the currency is being used by more than two states. The purpose of this study was to review the impact of the proposed single currency regime on the member states’ current ISBs in order to guarantee the proactive integration of the GCC into a viable economic bloc. The focus on the ISB is based on the assumption that the interest rates and financial regulations within each market are not uniform. Therefore, the single currency will balance any market swings and government regulations, as each state will have to adhere to uniform banking regulations based on Sharia, morals and faith. The fluctuating interest rates within the GCC will be reviewed independently to establish the potential impact of the single currency, the Gulf Dinar, within the banking industry.

This study focuses only on the banking sectors within Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and Bahrain because they did not request a suspension of the process of adopting a single currency regime. In order to determine the potential impacts of a single currency regime, the study concentrates on the Islamic banking regulations and interest or inflation rates in each state over an 11-year period (2002–2012). A co-integration analysis of the interest rates is used to establish the possible impact of a similar currency regime. This study was inspired by the need to add to the current pool of knowledge on Islamic banking from a monetary perspective in order to influence the potential policies that will be put in place to ensure that the Gulf Dinar promotes competitive banking in the GCC. Very little research has been done on the subject of a single currency regime within the ISB in terms of its sustainability and relevance. The findings of the present study will contribute to the existing knowledge on monetary regimes and financial models within the ISB. By filling the current research gap on the relationship between a single currency and a unitary Islamic banking system within the GCC, the present study will help policy makers to gain the optimal benefits of a single currency and reduce any negative impacts that it may have on the ISB. Lastly, the study provides a practical platform for carrying out research on financial systems within the ISB in the GCC to foster integration through the Gulf Dinar.

Limitations of the Study

No research has been done on the potential impact of the Gulf Dinar currency regime on the ISB as part of the GCC bloc integration. Thus, this paper cannot present comprehensive evidence that can be relied upon as a single source, as it is limited to only a few aspects of Islamic banking. The findings of this study may only provide knowledge on the general impacts of a single currency on Islamic banking toward promoting the integration of the GCC as an economic bloc. The findings can only be useful if they are integrated with other aspects of Islamic banking in order to quantify the exact impacts of the Gulf Dinar on the GCC banking sector. The specific financial institutions that practise Islamic banking included here must review the established impacts and relate them to other trends when making future projections.

Summary

Chapter 1 developed a comprehensive research background, objectives, significance, questions and limitations. These aspects form the basis of the subsequent chapters, which establish the potential impacts of the proposed single currency regime on the ISB in integrating four out of the six member states into an economic bloc.

Literature Review

Introduction

Chapter 2 examines the ISB within the GCC member states and how a unitary banking platform could affect the performance of the industry under a single currency regime. Specifically, it reviews the relevant theoretical and empirical literature and puts it into the perspective of the GCC region and the ISB. A comparative review was also carried out to relate the existing literature on the single currency regime and Islamic banking to the actual circumstances within the GCC in functioning as an economic bloc with a common currency in the four aforementioned states.

Theoretical Literature Review

Islamic Banking Systems

Islamic banking is a financial system that incorporates Islamic legal concepts, such as risk sharing without predetermined returns, into its practices. It is based on principles that comply with Sharia law (Jadresic, 2010). According to Aljifri and Khasharmeh (2006), the three pillars of Islamic banking are Aqeedah (faith), Sharia (regulations based on Islamic principles) and Akhlaq (the ideal underlying behaviour in financial practices). Thus, the main principle of Islamic banking is to create an Islamic-based banking system that respects Sharia law, has a definite value system and is guided by the Islamic faith (Frankel, 2013). The main Sharia law that guides the ISB is the ‘prohibition of receipt and payment of interest (Riba) from financial activities or trading of financial risks’ (Aljifri, 2008, p. 45). Sharia law demands that any Islamic banking model must use the concept of sharing gains or losses as the foundation upon which any financial contracts are executed (Barzegari, 2010).

The ISB has grown in popularity in the last decade, especially in the Persian Gulf. After the global financial meltdown in 2007, global financial focus has been directed toward the ISB because it was the least affected (Jadresic, 2010). The main reason for this can be attributed to its Sharia-compliant services that conform to the Islamic faith. According to Barth (2008), the ISB serves the interests of the Muslim community by offering customer-friendly financial products that do not ask clients to bear all of the market risks. These Sharia-compliant products were created to promote the economic emancipation of Muslims by ensuring that they are not subjected to the market-determined interest rates and other financial fluctuations predominant in the conventional banking systems across the globe (Berk, 2004). The ISB promotes equitable profit sharing between the banks and their clients (Frankel, 2013).

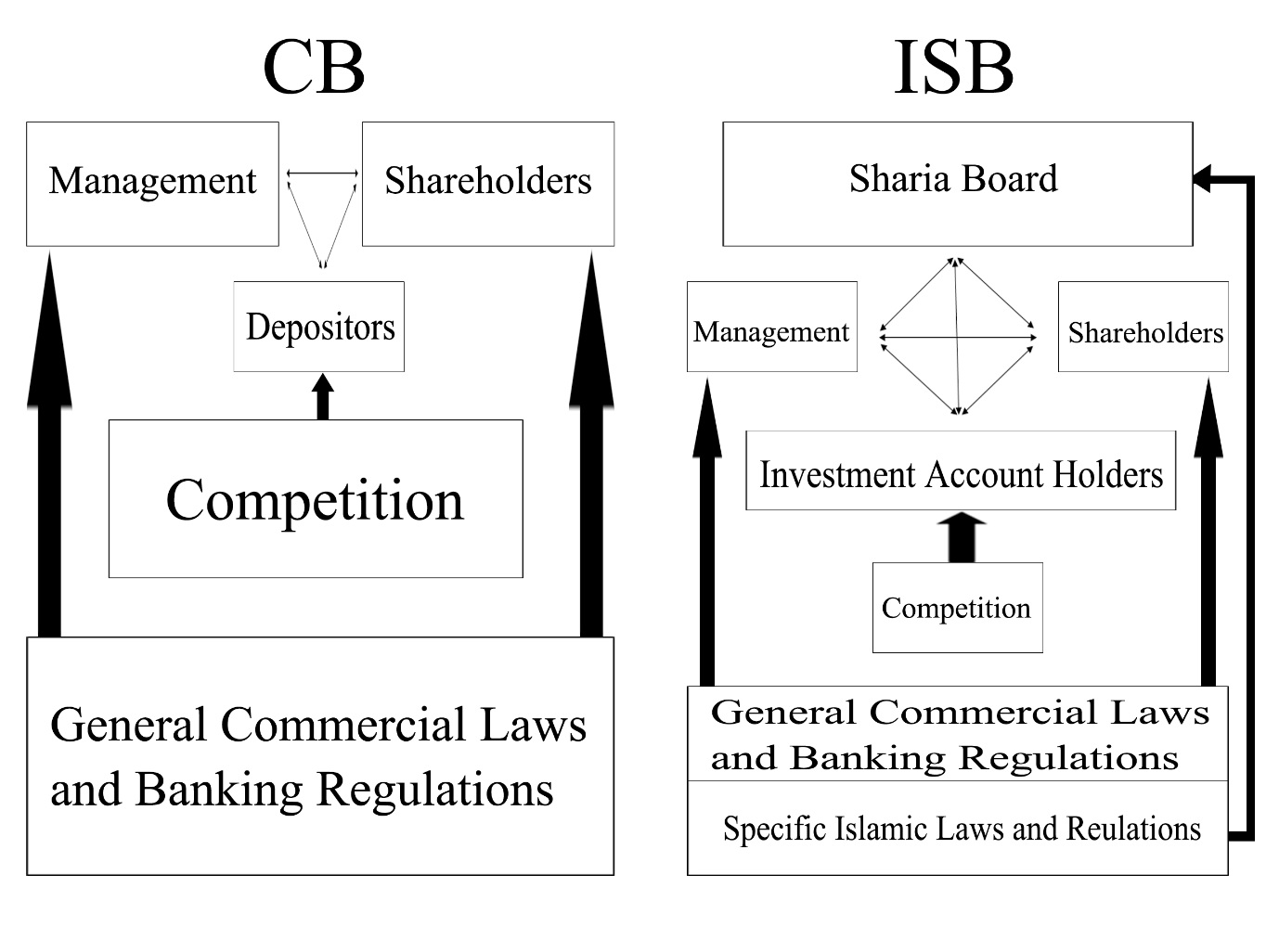

The ISB has metamorphosed from purely religion-based table banking into an independent institutionally based financial system that is especially prevalent in the Middle East and parts of North Africa (Dung, 2010). The ISB underwent a renaissance in the 1960s, becoming incorporated into financial institutions that do not charge any interest on loans to clients (Filip, 2010). In the Persian Gulf, where the GCC member states are located, the establishment of formal Islamic banking occurred after the Second World War following the growing global financial pressure to create a nationalised banking system. As noted by Joshi and Ramadhan (2002), the GCC nations consider the ISB to be very efficient, especially in utilising Sharia-based regulations. The post-millennium ISB within the Persian Gulf was promoted via the creation of different economic blocs such as the GCC, as this banking model is viewed as promoting a lasting partnership between all parties involved (Haber, 2004). The various ISBs are summarised in Figure 1 below.

Fig. 1: Islamic banking models (Joshi and Al-Basteki, 1999).

The Development of the Sharia-Based Banking within the GCC

The first known privately owned interest-free banking institution within the GCC was the Dubai Islamic Bank, which was founded in the 1975, followed by the establishment of the Kuwait Finance House in 1977 (Marquardt and Wiedman, 2004). Several banks emerged in1980 and after in Oman, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the UAE, Qatar and Bahrain. For instance, the Bahrain Islamic Bank was established in 1979, with Oman, Qatar and the UAE following suit in the same year (Hamdan, 2009). With the need to develop a unitary banking industry as part of the GCC pact, several high-profile conferences were organised in the 1980s and 1990s with the intention of determining an ideal model to adopt to create interest-free banking with a single currency regime (Marat and Shoult, 2005). During these conferences, the monetary council and the GCC integration committees agreed to incorporate the Hadith and Koran into the guidelines as well as to exclude Riba (interest on loans) (Ho, 2001). In addition, the banking regulatory institutions in each state were merged into a unitary Islamic banking model that set rules on Gharar (market uncertainty) and thresholds for products considered Haram (forbidden financial products) (Ohlson, 2009).

These policies were created because ‘the most important feature of ISB is that it promotes risk sharing between the provider of funds (investor) on one hand and both the financial intermediary (the bank) and the user of the funds (the entrepreneur)’ (Marquardt and Wiedman, 2004, p. 28). The financial committees charged with creating a unitary ISB for the GCC drafted policies that banned speculative and hedging financial transactions. In other words, all derivatives considered to go against Sharia law were banned and excluded from the pact (Thinggaarda and Damkierb, 2008). These committees created the Islamic Financial Services Board to investigate potential risks and to design strategies to address these risks. Despite the numerous benefits of the ISB, it has its drawbacks, such as greater operational and credit risks (Marat and Shoult, 2005). In relation to the GCC, creating a unitary banking industry is very easy since all the interested member states have functional ISBs guided by the same laws and regulations (Barzegari, 2010). The challenge lies in minor institutional variations in how these systems are managed (Hellstrom, 2006). Further, each nation currently operates different currency regimes. Each currency has a different value placed on it depending on the level of inflation in the state. A single currency regime would likely address these institutional challenges since the Islamic banks within the GCC would share a currency and banking framework (Filip, 2010).

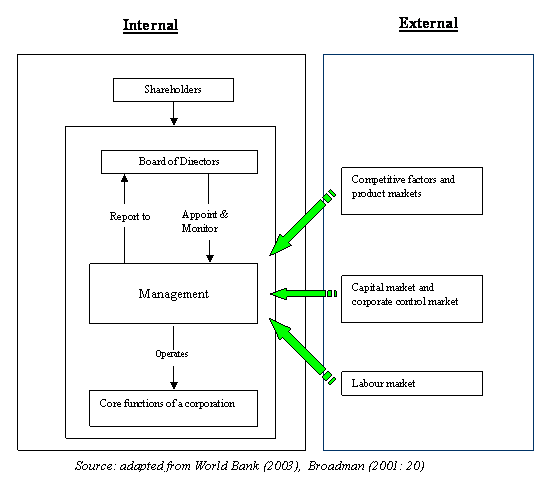

Theory Related to Single Currency: Outsider-Insider Model

Within the Persian Gulf, most Islamic banks are privately owned. There are more private banks within the GCC than banks owned by the member states (Joshi and Al-Basteki, 1999). This situation could make it difficult to integrate the financial markets into a single banking industry. For instance, the GCC integration committees may have to acquire a functional process for separating control and ownership interests in the bid to create a unitary banking sector(Wang, 2010). In addition, despite the fact that most of the banks within the GCC are run in accordance with Islamic beliefs, their corporate governances differ (Verriest, 2007; Haber, 2004); thus, it has become a challenge knowing how to create a uniform corporate governance and control system that is applicable within the banking sectors of the member states (Joshi and Ramadhan, 2002). Another challenge impeding the adoption of a single currency regime within is the diminished independence to create a monetary policy within each market (Ho, 2001). For instance, it would be difficult to create uniform wages, prices and productivity structures within the banking system without interfering with the independence of each state. It would also be difficult to merge the exchange rate policies of each state when the monetary union has been implemented, especially in the dynamic banking sector when implementing the optimum currency area (OCA)(Hung, 2001). The OCA refers to the integration of more than one state through a single currency to form a monetary union. According to Qystein and Frode (2007), ‘economies forming a single currency union would be in a better position to absorb the asymmetric shocks if the integration criteria are logically met’ (p. 51). The outsider–insider model is summarised in Figure 2.

Accounting Theories Related to Islamic Banking

The accounting theories analysed in the current study include agency, trade-off and pecking order premises. In agency theory, Aljifri and Khasharmeh (2006) explain that Islamic-based financial institutions should promote risk sharing among the stakeholders, including the depositors, shareholders, creditors and bond holders, to ensure that profit generation does not override the stakeholders’ interests. In the ISB, the capital is located on the liability side and does not guarantee protection from risks that are associated with risky assets, as all of the stakeholders must share these risks (Hung, 2001). Thus, any available capital cannot be withheld because it is the primary source of funding (Barzegari, 2010). In agency theory, debt and equity as part of the capital structure determine the general performance of Islamic financial institutions (Qystein and Frode, 2007). Therefore, debt in ISB has a significant influence on the general performance of these financial institutions (Joshi and Al-Basteki, 1999). For instance, debt heterogeneity may affect an institution’s performance and leverage ratio irrespective of the risk factors or sensitivity of the financial market. Agency theory is a modification of capital structure theory, which was developed by Modigliani and Miller in 1958 (Marat and Shoult, 2005). In the ISB, equity weight as part of the capital has a minimal effect on the firm’s value (Marquardt and Wiedman, 2004). Agency theory is relevant in this study because it facilitates the understanding of the operational risks that might arise from the monetary union under the unitary ISB in the GCC (Ohlson, 2009). Further, agency theory provides a preview of the trade-offs, operational costs and imperfections of the financial markets.

Trade-off theory, as applied within Sharia-based financial markets, views the optimal debt level as resulting from financial distress costs and tax advantages (Qystein and Frode, 2007). This theory is based on the assumption that financial institutions with higher financial risks are bound to borrow less as compared to their counterparts with lower financial risks. In the general market environment, the level of financial distress differs across institutions and is dependent on their assets (Thinggaarda and Damkierb, 2008). Since assets in the ISB are jointly owned, risks are easily transferred.

Lastly, pecking order theory is an accounting model stating that financial institutions often issue debt because their internal cash flows cannot meet their dividend obligations and real investments (Verbeek, 2008). Thus, the easiest way out of financial distress is to issue the safest security in the form of investment debt (Verriest, 2007). Moreover, when the financial distress is persistent, this theory is instrumental in explaining the relationship between the debt and profitability ratio within the ISB (Vinod, 2008). This theory will facilitate the understanding of the capital structure of the unitary banking industry within the GCC.

Empirical Literature Review

Sharia-Based Banking in the GCC Region

Since the states making up the GCC already have a Sharia-based ISB, there are several benefits that could occur if the monetary union is adopted. In a study on how the monetary union will foster integration within the GCC, Frankel (2013) identified potential financial improvement as a result of the integration of factor, service and financial markets. In a similar study, Thinggaarda and Damkierb (2008) reported that a monetary union within the GCC would facilitate the ‘elimination of the exchange rate risks for trade flows among the monetary union members, especially within the banking sector’ (p. 19). Marquardt and Wiedman (2004) investigated the benefits and potential costs of the GCC monetary union, finding that a single currency regime would reduce the costs associated with transactions in the banking industry and boost the international currency reserves that are held by the unitary central bank; this is because banks within the member states would be excused from holding international reserves that are meant for transaction with the single currency.

Joshi and Ramadhan (2002) noted that through coordination of the fiscal and monetary policies through the monetary union within the GCC, the unitary banking industry would have stable prices, leading to economic growth and a competitive economic bloc. In order to complete the integration of the monetary union, the GCC should develop stronger institutions (Marat and Shoult, 2005). For instance, the GCC should consider developing stronger regional financial institutions in order to control the ISB through standardised monetary control (Hamdan, 2009). Due to the lack of a stable supranational financial institution within the GCC, the proposed central bank should incorporate the fiscal and financial data from the banks of each member state to boost integration and guarantee transparency (Jadresic, 2010). When the above conditions are met, it is likely that the GCC would see well-coordinated currency decisions made by the current Supreme Council in terms of structural, regulatory and fiscal policies, as was observed in the study of the EU conducted by Wang (2010). The differences between Sharia-based banking and conventional banking are summarised in Figure 3.

Optimum Currency Area in the GCC Banking Industry

Several scholars have carried out studies to quantify the benefits of a single currency regime on financial markets. For instance, Joshi and Al-Basteki (1999) succeeded in creating a model for quantifying the impacts of a single currency regime on financial markets. Fortunately, the model can be applied to the GCC’s unitary banking industry under the single currency regime because the member states are homogenous, with a single language and religion that dominate their banking practices. Wang (2010) concluded that integrating the GCC through a unitary banking system would be facilitated by a monetary union since the member states have a lot in common in terms of their financial and banking policies. Qystein and Frode (2007) reported that enhanced fiscal discipline within the banking industry in the GCC might facilitate the reinforcement and integration of the financial markets, increasing the competence of the financial services. After carrying out a co-integration analysis of certain financial markets, inflation rates and monetary policies within the GCC member states, Marquardt and Wiedman (2004) concluded that the above variables had a positive co-integration. This implies that the member states have similar financial performance trends that are linked by their monetary policies and financial markets (Joshi and Al-Basteki, 1999).

Espinoza, Prasad and Williams (2010) proposed that financial integration within the GCC would have a positive correlation with interest rates, capital flow and equity prices. However, the same study also established that a monetary union within the GCC unitary banking industry would distort inflation due to differences in the tax regimes within each banking sector (Ho, 2001). Because there are limited distortionary taxes within the GCC member states, a monetary union would guarantee the negative benefits of such taxes at the governmental level. Each member state has divergent monetary policy instruments, and Frankel (2013) established that ‘the open market operations, using treasury bills and government development bonds, foreign exchange swap operations, central bank certification of deposits, and reserve requirements are only limited to prevailing exchange rate regime and free capital mobility’ (p. 147).

From these empirical studies, it is apparent that interest rate stability and convergence are very possible within the banking industry in the GCC when the single currency regime is finally introduced. Since the primary goal of the integration of the GCC into an economic bloc is driven by price stability, the monetary union would guarantee effective financial market shock synchronisation, as the similar ISBs would result in symmetric shocks (Aljifri and Khasharmeh, 2006). Implementing the EU monetary regime in the midst of a conventional banking system was effective because the single currency regime could synchronise the symmetric and asymmetric shocks affecting the financial markets of more than 95% of the member states (Aljifri, 2008). However, developments in 2016 have tested the Euro’s competitiveness. In the GCC bloc, the main financial shocks would be symmetric, as the banking systems within the member states are Islamic-based. This similarity makes implementing a single currency a viable alternative, as it would be easy to execute price levels and a real effective exchange rate (REER) (Filip, 2010). Further, the potential monetary shocks caused by financial market supply and demand shocks would have very limited effects on the unitary ISB in the long-run.

Application of Single Currency in the Islamic Banking System within the GCC

The banking industry within the GCC is dominated by the ISB; it must adhere to the standards set by the Accounting and Auditing Organisation of Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) (Marat and Shoult, 2005). This organisation controls ethics, auditing, governance and accounting by applying Sharia standards to Islamic banking. Despite the fact that the market structures are slightly different within the GCC member states, the Herfindahl-Hirschman index suggests that the Qatari, Omani and Bahraini banking sectors are more concentrated than their counterparts in the UAE, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia (Joshi and Al-Basteki, 1999). Several studies have suggested that the ISB has been more effective within the Persian Gulf than other conventional banks because it promotes cost effectiveness and stable liquidity ratios.

For instance, studies by Aljifri and Khasharmeh (2006), Joshi and Al-Basteki (1999) and Qystein and Frode (2007) reported that the ISB has become very convenient and effective in the GCC because the member states have similar guidelines for controlling the operation of their Sharia-based accounting policies. Despite the fact that the ISBs that are currently in place within the GCC operate with different currency regimes, the proposed monetary union would likely improve the performance of the banking sector, especially in terms of accounting policies and financial market controls (Ho, 2001). This is because the single currency regime would synchronise the current accounting practices that are already Sharia compliant into the best standardised practices, creating a unitary banking industry (Wang, 2010). A single currency regime within the Sharia-based ISB in the GCC would likely improve the competitiveness of the reserves that are available from a centralised bank, as opposed to the current policy that requires each independent bank to hold a certain amount of reserves (Haber, 2004). Therefore, a single currency regime could make it easy for the banking industry to balance the symmetric and asymmetric financial market shocks, facilitating competitive accounting practices within the ISB.

Findings from the Literature Review

From the above literature review, it is apparent that the current banking industry is dominated by the ISB. The six member states already use Sharia-based banking systems despite having different currency regimes. Since the GCC financial markets are homogeneous, that is, influenced by similar factors such as religion-based accounting, oil prices and similar financial market trends, the literature review indicates that a monetary union would be beneficial to the banking industry. The primary merits of a single currency regime within the ISB in promoting the integration of the GCC as an economic bloc include increased reserves from the central bank, standardised monetary and fiscal policies, improved capital flow and reduced supply and demand market shocks. Further, a monetary union would facilitate standardised interest rates and improved banking sector performance, as inflation pressures would be contained. From a theoretical perspective, an optimal currency area regarding supply and demand within the ISB is practical when the outsider–insider model is integrated, as it would eliminate the differences in inflationary pressures and financial shocks currently in existence in each market.

Research Gap

Despite the series of studies on ISBs and a monetary union within the GCC, to the researcher’s knowledge, no study has examined the potential impacts of a single currency regime on the ISB. This paper attempts to fill this research gap by establishing a link between the monetary union and the ISB in promoting GCC integration.

Summary

The above literature review indicated that a monetary union would make the ISB within the GCC more competitive and promote integration into an economic bloc. Specifically, a single currency regime would be instrumental in promoting financial market stability, especially with the homogenous application of the Sharia-based banking and accounting controls already in use in the GCC member states. The need for a monetary union is inspired by the desire to balance market shocks, create a dynamic centralised reserve and modify the current fiscal policies to integrate accounting standards that are applicable within the ISB.

Methodology

Introduction

Chapter 3outlines the method used for data collection and analysis. Since the study focuses on the ISB within the GCC, the researcher applied snowball sampling to collect data to complete the quantitative study. The rationale for choosing quantitative analysis was informed by the need to develop a deeper understanding of the different attributes of Islamic banking that might be affected by the proposed single currency regime (Verbeek, 2008). The research targeted banking and financial institutions that practise Islamic banking within the GCC region. The researcher examined the collected data for patterns in the interaction between the variables of Islamic banking that are impacted by a single currency regime in the context of the GCC’s integration into an economic bloc (Frankel, 2013). The quantitative approach is ideal for identifying emerging statistical patterns from the data collected in close association with the study variables (Verbeek, 2008). This chapter reviews the research approach, data analysis, ethical aspects of the research, research techniques and the quantitative data analysis tools used.

Research Approach

Since the scope of the research was dynamic, narrow and subjective, quantitative analysis was sensible because it accommodates a series of data analysis tools and a small error margin (Verbeek, 2008). The researcher used the appropriate statistical tools when carrying out the quantitative analysis on the collected data. The collected data were then transcribed in order to identify emerging trends in the form of divergent and convergent results (Verriest, 2007). In the process of collecting the secondary data, the researcher was careful to observe the scientific data collection steps to ensure that the final results were within the acceptable degree of accuracy (Vinod, 2008). The data were used to test the independent variables of CPI and GDP as impacting the shocks within the ISB in the GCC; the single currency served as the dependent variable.

Research Samples

Sampling

The researcher applied snowball sampling when choosing which financial institutions to analyse. Snowball sampling was ideal since the researcher intended to identify trends that could be generalised to represent the entire banking industry within the GCC economic bloc (Wang, 2010). For instance, the researcher was careful to review private and public financial institutions to ensure that the results could be related to the entire industry irrespective of the dynamics in each financial market (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 2008).

Data Analysis

After collecting secondary data and carrying out data transcription, the data were analysed. The researcher used the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), were used for trend tabulation to examine the actual impact of the proposed single currency regime on the ISB. As noted by Creswell (2009), it is important to quantify the independent and dependent variables through correlation analysis in order to generate charts, tables and figures that can support the analysis. The application of the data analysis in the present paper will be discussed in Chapter 4. Data decoding was carried out to encompass ANOVA by deriving the mean differences in the data sets (Wang, 2010). ANOVA was used to find the existing variances in the mean for each of the data sets.

Generalisation and Vigour

The sample was representative of the financial markets that practise Islamic banking within the GCC and of the general financial market within the targeted industry. It left room for comparative research, especially in testing the accuracy and degree of freedom at different intervals (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 2008). Considering the above factors, the data collected can be predicted to be scientific, accurate and representational of the present research aims and objectives (Verbeek, 2008).

Validity and Reliability

According to Blank (2011), reliability and validity determine the scope of accuracy of the collected data in the course of the research. In this case, validity was achieved by pre-testing all of the research questions against the primary objectives of the project. Reliability was ensured through different research instruments such as regression model which are consistent with the aim of creating a standard outcome (Hamdan, 2009). Since this paper observed the aspects of validity and reliability, it is predicted that the results will‘reflect the unique understanding that personal experiences bring to the development of case study’ (Creswell 2009, p. 23). The integration of the secondary data collected was balanced in order to incorporate relevance and competencies of the study (Frankel, 2013). Before including a set of secondary data in the analysis, the researcher conducted eligibility tests to meet the scientific guidelines for carrying out data analysis.

Ethical Concerns and How They Were Addressed

The researcher had experience carrying out scientific research, making it easy to practise credibility since data gathering and reporting were well managed. The concept of transferability was observed through reviewing the collected data in a concurrent manner (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 2008). In order to achieve research dependability, the researcher carried out detailed, sequential data cleaning techniques within the confines of the study design. Thus, each variable of the research was strategically positioned to be congruent with the study’s aims, objectives and questions (Blank, 2011). This laid the foundation for applying theoretical constructs to different analytical frameworks of the study. The research was accurate in transcribing the data sets in conformity with scientific study standards (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 2008).Being a scientific study, the researcher ensured that the usage and scope of the data were within general research ethical guidelines. In addition, the processes used for secondary data collection, testing and analysis were scientifically reviewed to guarantee a balance between the samples and market dynamics (Creswell, 2009).

Research Techniques

Degree of Confidence Estimation

The study’s confidence interval was set at 99%. This is further explained below.

Sample statistic + Z value * standard error / √n:

b1 = 7.1175 ± 2.57 * 0.9631 / √133 = 7.1175 ± 2.57 * 0.9631 / 11.5326 = 7.1175 ±0.2146 = 6.9029 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.3321

At 95%:

b1 = 7.1175 ± 1.96 * 0.9631 / √133 = 7.1175 ± 1.96 * 0.9631 / 11.5326 = 7.1175 ± 0.1635 = 6.954 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.281

At 90%:

b1 = 7.1175 ± 1.64 * 0.9631 / √133 = 7.1175 ± 1.64 * 0.9631 / 11.5326 = 7.1175 ± 0.1368 = 6.981 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.254

As indicated in the calculations, the confidence intervals were estimated at 6.981 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.254 of 90%, 6.954 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.281 of 95% and 6.9029 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.3321 of 99%. The above values indicate that the estimated confidence interval increased as the interval decreased.

Multivariate Threshold Autoregression (MVTAR) Model

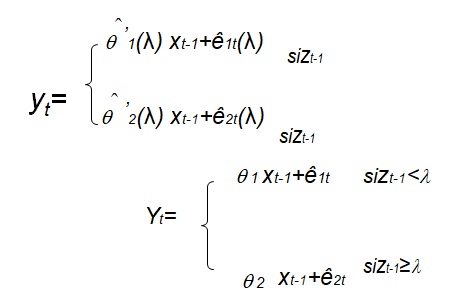

The MVTAR model served as the primary empirical tool for testing the null hypothesis. Here, the researcher identified the following threshold model:

where t=1(T;xt-1= (yt-1r’tyt… yt-k)’;e1t ); e1t , zt, and e2t are the switching variables;

rt is the deterministic component vector and λ denotes the threshold (λ = [λ1, λ2] with p(zt≤ λ1) =0.15).

In order to estimate the above model equation, the researcher adopted the methodology proposed by Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias (2008); it computes the variance of the thresholds via an ordinary least square test.

Thus the proposed equation can be summarised as

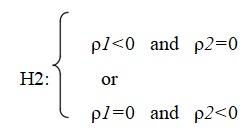

In the above model, the researcher assumed a confidence interval of 99% to test the hypothesis (H0: λ = λ0 ), with the likelihood being commutated as LR (λ0). Using the above estimations, the researcher carried out linearity tests using the threshold effect and stationarity tests. With the threshold effect test, the researcher attempted to pinpoint a possible threshold effect, which must disappear in order for the null hypothesis (H0: θ1=θ2) to hold. This was achieved by using the Wald statistic (Wt)because it is a simple decreasing function. It is important to note that the Wald statistic is predetermined with a residual variance that can be integrated into the MVTAR model. Creswell (2009) suggested that approximation of the threshold should be within the 99% degree of confidence in order for the null hypothesis to hold. In performing the stationarity test, Blank (2011)argued that the existence of non-stationarity within a data set has an effect on asymptotic distribution when performing the threshold test: ‘the asymptotic distribution is non-pivotal and depends on the nuisance parameter function’ (Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias, 2008, p. 45). Wang (2010) presented critical values that can be used to perform the stationarity test as part of the MVTAR model adjustment as a primary accounting principle. In line with this, the hypotheses tested in the present study are the null and alternate hypotheses presented below.

H0: ρ1= ρ2=0 (null hypothesis)

H1: ρ1<0 etρ2<0 (alternate hypothesis)

In order to effectively test the above hypotheses, the researcher used the third hypothesis formulae proposed by Creswell (2009).

When the H0 is accepted, the MVTAR (yt) is integrated as representational of order 1. When H2 holds, the yt will assume the position of a unit root process in a single scenario and will be stationary in another scenario. However, Frankfort-Nachmias and Nachmias (2008) stressed that testing the H2 cannot differentiate the null and alternate hypotheses because it examines the hypotheses concurrently.

ANOVA

The researcher used ANOVA to substantiate the variance in the means of the different data sets (Frankel, 2013). The first element that was calculated was the variance between the mean of each country in terms of CPI and GDP, which is denoted by ![]() . The second element

. The second element ![]()

calculates the variance between the GDP and CPI of the GCC member states (Vinod, 2008).

Findings and Analysis

Introduction

Chapter 4 explores the study’s statistical findings. It reviews and tests the data gathered in order to derive scientific meaning. Specifically, Chapter 4 examines the secondary data in detail and carries out correlations, ANOVA and hypothesis testing to establish the emerging trends in examining the proposed single currency regime on the ISB within the GCC. The entire chapter is based on accounting principles in order to examine the potential impacts of a monetary union within the banking industry in the proposed unitary GCC financial market.

Quantitative Analysis

The researcher used data from the six GCC countries, the UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman and Bahrain, from 2002–2012. The main sources of the secondary data were the World Development Indicator, International Financial Statistics and the statistical database for the United Nations. Vector autoregression was used to code the collected data because it enabled the researcher to carry out variance decomposition and review the financial shocks in terms of how the member states responded. The researcher used the MVTAR model to test the non-linearity in the monetary union model within Islamic banking.

The Data

In applying the MVTAR model, the researcher tested the variables’ stationarity and co-integration relationships. The data were used to test the independent variables of CPI and GDP as impacting the shocks within the Islamic banking industry in the GCC, with the single currency as the dependent variable; the researcher used the price parity (PP) est proposed by Creswell (2009). This was ideal for testing the unit root hypothesis in order to pinpoint the stationary series. The results are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2: Stationary test results (Wang, 2010).

As can be seen in Table 2, the co-integration test indicates that there is no co-integration correlation between any of the GCC countries, except for in Bahrain. This test was necessary in order to examine the MVTAR model used for calculating the impulse functional responses and decomposition of the variance. Thus, the MVTAR model was used to observe the effect of the unexpected shocks in the financial markets on the research variables (Wang, 2010). Table 1 also reveals that the GCC countries using the ISB have a positive symmetrical response to financial market shocks. This is illustrated in Appendix 1 (summarised in Figures 1 and 2).

Interestingly, the findings indicate that all six countries that use ISB initially had a symmetrical response to financial shocks. The shocks stabilised in 2006 in Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Oman; however, it took longer for the financial shocks to stabilise in Kuwait. In the UAE, the financial shocks increased in 2003 before falling again and stabilising in 2009. In general, these shocks are symmetrical, especially when related to GDP. In relation to the CPI shocks, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Saudi Arabia had negative symmetrical shocks during the first and second periods of analysis. The countries stabilised their shocks in 2005, except Bahrain, which experienced continuous shocks. This result indicates two asymmetrical shocks: Qatar and the UAE. However, the shocks later stabilised in 2008. The asymmetrical shocks in Qatar and the UAE may be associated with their greater dependency on the service industry to support the financial sector.

In Table 3, the variance decomposition for the GDP and CPI within the GCC banking industry is presented for the 11-year period. Specifically, the results suggest that Saudi Arabia is the only GCC member state that is not actively influenced by the actions of the other states within the banking industry. However, Kuwait and the UAE are actively influenced by the policies and actions within the banking sector in Saudi Arabia. In the case of the banking sector in Bahrain, influence emanates from Oman, Kuwait, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. In Qatar and Oman, the greatest level of influence emanates from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. Thus, the results suggest that Kuwait and Saudi Arabia’s financial markets have the most influence on the other GCC member states practising Islamic banking in terms of GDP shocks. In relation to the CPI decomposition variance, Table 2 indicates that Oman and Kuwait are free from any influence from the other GCC member states, especially within their financial markets. Bahrain is the only GCC member state that is heavily influenced by other member states. Actions within the financial markets in Saudi Arabia are only influenced by Oman. Moreover, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia influence the financial market performance in Qatar, as summarised in Figures 3 and 4.

In order to carry out further analysis of the monetary union and the ISB in the GCC, the researcher considered potential non-linear links between the macroeconomic variables using the MVTAR model. The primary intention in using this model was to examine the non-linear traits of time series vectors and estimate impulse functions (Blank, 2011). These aspects were critical for identifying and analysing the symmetrical shocks within the ISB in the GCC. When applying the MVTAR model, the researcher assumed that the existence of a non-linear threshold link in the MVTAR model would necessitate differentiation of the switching variable threshold. In this case, the researcher anticipated that the switching variable would be oil prices, as the member states are dependent on oil as the primary source of earning foreign exchange (Ho, 2001). The researcher then performed variance decomposition within the MVTAR model to examine the potential impacts of oil prices on the macroeconomic variables in the ISB in the GCC. The results are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3: The linearity test results.

The results shown in Table 3 indicate that a non-linearity hypothesis is acceptable within all of the member states, justifying the use of the MVTAR model. The results also indicate that the threshold value is more or less similar in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Bahrain at 0.7052, 0.8071 and 0.8490, respectively. Qatar and the UAE have a similar threshold value of 0.0000. Lastly, Oman has a threshold value of 0.1636. These threshold values indicate that the GCC member states can be segmented into two groups. The first group consists of member states with high thresholds (Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia). The second group consists of member states with low thresholds (Oman, the UAE and Qatar).

Discussion and Recommendations

Introduction

Chapter 5 summarises the findings from the data analysis and relates these results to accounting aspects, such as the IFRS, and its implications for regulations within the ISB in the GCC. It also explores auditing and the existing controls within the banking sector in the GCC from the controller institution perspective. In addition, it relates the findings to the literature review in order to substantiate the Islamic banking perspective of accounting. Finally, it suggests areas for further research inspired by the limitations that restricted the scope of this study.

Discussion

All of the GCC member states seem to be experiencing similar responses to the financial shocks within the ISB. Despite the different amounts of time it takes for each member state’s banking sector to stabilise following the shocks, eventually, they all recover in a similar manner. Oman, Qatar and Saudi Arabia recovered more quickly than the remaining member states due to their more stable financial sectors. The financial instability in Kuwait is responsible for the longer period of recovery within its banking sector. The same instability prolonged the recovery period from the financial shocks in the UAE due to strict implementation of the IFRS in 2007 (Dellas and Tavlas, 2009). The transition to the IFRS controls had a ripple effect in the financial markets of the GCC member states because it introduced global control trends in accounting within the ISB. These controls standardised accounting principles on disclosure, ethical financial reporting and litigation. In general, the shocks in 2006 within the GCC member states can be attributed to the adoption of the IFRS as the primary accounting standards used in the ISB (Wang, 2010).

In relation to the ISB model applied within the GCC and the monetary union proposal, the shocks that occurred after 2006 are symmetrical and uniform in all of the member states’ financial markets. With reference to the GDP and CPI, there were negative symmetrical shocks in Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kuwait and Bahrain at the end of 2008, with stability beginning in 2010. The results of the analysis also indicated negligible asymmetrical shocks within the UAE and Qatar in the same period (Dellas and Tavlas, 2009). However, these shocks were ignored before they self-corrected over a period of less than one year. The asymmetrical shocks within the UAE and Qatar could be related to their over-dependency on the service industry as the main pillar supporting the financial markets, which was greatly affected by the global financial meltdown of 2008. The CPI and GDP variance decomposition in the ISB within the GCC suggests that the dynamics in each financial market affect each member state, with the exception of Saudi Arabia. Due to the excessive divergence of the Saudi economy, the actions of other member states have little or no effect on its financial market (Verriest, 2007). The UAE and Kuwait are most affected due to their over dependence on the service industry, which is very unstable and often influenced by external forces.

From 2006–2016, the implementation and acceptance of the IFRS within the GCC financial markets has brought several benefits to the ISB. First, it has streamlined the ISB into an efficient and stable financial market that can support the integration of the GCC member states into a single currency regime (Dellas and Tavlas, 2009). As already discussed, the integration of the IFRS has created an ideal financial market and synchronised the dynamics in each banking sector of the GCC member states into a symmetric banking industry that experiences similar GDP and CPI shocks (Blank, 2011). Thus, the six member states all have the desire to share financial opportunities that come from a synchronised financial market through the integration of the IFRS in the ISB. Through internalising the underlying regulatory regime and controls associated with the IFRS, the six member states have created a dynamic, self-regulating and competitive ISB that will foster integration (Verriest, 2007).

The integration of the IFRS as an accounting principle within the ISB in the GCC market has created an environment of value relevance, especially in publicly owned financial institutions. Before the introduction of the IFRS, CPI and GDP shocks within the banking sectors of each member state were erratic, unpredictable and asymmetric (Wang, 2010); however, this trend changed in 2006 when all of the member states adopted the IFRS. This is visible in the symmetric trends in the CPI and GDP shocks after 2006, which stabilised in 2008 despite the global economic meltdown (Verries, 2007). The stability of the financial markets within the GCC at the height of the global financial meltdown can be associated with the self-regulating nature of the ISB, which is based on strict adherence to Sharia law. The comparative results analysis from the above data indicates that there is a distinct difference in the performance of the banking sector before and after the adoption of the IFRS within the ISB (Blank, 2011). These results can be interpreted to mean that IFRS adoption improved the accounting principles and guidelines already in place, producing positive results within the banking sectors of all six member states (Verriest, 2007).

In relation to the literature review, the findings confirm that adopting the IFRS in the Middle East, especially within the GCC, brought about accounting reforms that have liberalised the current ISB. Specifically, it motivated the development and maturation of synchronised financial markets. For instance, in the six member states, the IFRS is responsible for improved accounting practices, which are characterised by better performance (Ho, 2001). The quality and value attached to the IFRS is responsible for the improved level of satisfaction with the current ISB. The factors that make the IFRS beneficial include quality, ethics and fair practices, creating a competitive banking and accounting model. The high-quality IFRS regulations have created an environment of reliability, relevance, consistency and comparability in financial reporting in line with Sharia law (Wang, 2010).

When combined, the above factors resulted in improved performance of Islamic banking and the synchronisation of each financial market toward a single currency regime. The acceptance of the quality dimensions controlled by the Special Monetary Committee within the GCC has created a standardised Islamic accounting regulatory authority that is accepted by all of the member states (Buiter, 2008). For instance, in reinforcing the value relevance, the auditing role is allocated to the regulatory authority on behalf of each financial market in order to ensure that fair and acceptable Islamic accounting practices are upheld. The controls are further streamlined by the Special Financial Integration Agency that is charged with developing an auditing framework and tracking its implementation. This is necessary to ensure that all stakeholders’ interests are considered, conforming with Beaver’s (2011) observation that the ‘theoretical groundwork of value relevance studies is a combination of valuation theory plus contextual accounting and financial reporting arguments that allows the researcher to predict how accounting variables influence performance of financial systems’ (p. 35).

The above findings support the literature review on Islamic banking, the IFRS and controls that are in place to ensure that synchronisation of the financial markets results in integration of the GCC member states into a single currency regime. Integration of the IFRS into Islamic accounting in the GCC financial industry has several benefits: efficiency, effectiveness and competitiveness of the current Sharia-based banking approach (Creswell, 2009). Specifically, the six member states that have adopted the IFRS have more stable and better-performing financial markets that conform to Islamic banking regulations. Further, the stability in the GCC financial industry after the IFRS adoption has become the focus of the Special Joint Committee on Monetary Union. It has enabled the committee to reinvent the ISB’s strategic auditing framework to facilitate financial reporting and streamline its operations (Verriest, 2007). The post-IFRS Islamic accounting model within the GCC is characterised by neutrality, competitiveness and completeness. The performance of each financial market under the ISB has become predictable, understandable and comparable when all other factors are held constant.

Due to the existence and operation of similar Islamic accounting models within all of the member states, the integration of the IFRS and a single currency regime into the ISB would lower transaction costs and improve the currency reserves held by each financial market (Hamdan, 2009). In other words, the central unitary bank could hold more reserves while complying with Sharia law to improve the competitiveness of the GCC banking industry (Verbeek, 2008; Zaidi, 2010). The controls applicable to the ISB under the IFRS would be well coordinated, well structured and policy-oriented for a stable single currency ISB (Vinod, 2008). However, it would be prudent to monitor the variations caused by the different economy sizes and levels of influence of each member state.

Case Study of Saudi Arabia’s Financial Market

Saudi Arabia’s banking industry has excelled in the post-IFRS implementation period, as shown in Table 1. Following the full implementation of the IFRS in Saudi Arabia in 2006, the banking sector, which employed the ISB, became more stable and predictable, as indicated in the coefficient in the financial market (increasing from-0.890795 to -0.890209) (see Appendices 2 and 3). The integration of the IFRS into the ISB in Saudi Arabia has synchronised its financial market. For instance, accounting information has been streamlined and balanced to serve the interests of the stakeholders operating in the dynamic Sharia-based banking industry (see Appendix 3). Thus, the application of the controls in Islamic accounting practice have made it easy to integrate the different dynamics in each financial market with the aim of creating a competitive, sustainable and reliable single currency regime in Saudi Arabia in the pre- and post-IFRS adoption periods (Frankel, 2013).

Since the banking industry in Saudi Arabia already practised Islamic banking before it adopted the IFRS, synchronising the financial market into a single currency regime in the post-IFRS period was relatively easy because it is easy to foster integration from an accounting perspective due to the common interests and similar variables in play regarding monetary union (Wang, 2010). For instance, it is not difficult to integrate the service, regulatory factors and market environment in the Saudi banking sector. In addition, this step saw the complete’ elimination of the exchange rate risks for trade flows among the monetary union members, especially within the banking sector’ (Jadresic, 2010, p. 19). The IFRS adoption unified a series of accounting systems, strengthening the accounting profession in the entire GCC region. Adopting the IFRS integrated Saudi accounting standards with regard to employee benefits and property investment despite variations across companies. Also, the application of legal regulation under the stewardship of the Saudi Organization for Certified Public Accountants (SOCPA) made the accounting environment more competitive. The organisation spearheaded inclusiveness, rehabilitation and training to ensure that the accounting standards within the banking sector adhere to international expectations (SOCPA, 2016).

Areas of Future Research

Since this study was based on empirical data determining the impacts of a single currency regime on the ISB in integrating GCC member states into an economic bloc, the findings are limited to the period under study and the dynamics in play at the time. Thus, the findings might not be completely representational of the current situation, especially in terms of any progress toward a single currency regime within the unique ISB. Each member state’s interests might change, altering the integration process. The findings of this study may only indicate the CPI and GDP trends within the ISB in relation to IFRS adoption and potential monetary union. Thus, there is a need to identify other factors in addition to the IFRS and the ISB that might be responsible for the improved performance trend observed here. Also, variations in the economy size and level of influence of each member state should be considered in any future research.

Conclusion

The IFRS adoption would result in alignment of the financial market shocks under the Islamic banking system when the single currency regime is adopted within the GCC. However, institutional elements might become obstacles in the integration of the GCC as an economic bloc due to differences in economy size, financial systems and level of political influence. These challenges could create obstacles impeding the integration of the GCC, especially with the unique ISB already in place; this is despite the uniformity of the IFRS standards within each member state. The findings indicated that all of the GCC member states experienced similar responses to the financial shocks within the ISB both before and after the IFRS introduction. Specifically, the GDP and CPI shocks were asymmetric before the IFRS adoption and symmetric after its adoption. The findings also suggested that the IFRS standards have improved the performance of the Sharia-based Islamic accounting system in place within the GCC financial industry. The results from the regression approach indicated a general synchronisation within the ISB after the IFRS adoption by all of the member states. The results can be interpreted to mean that the IFRS adoption and integration within the ISB in the GCC was responsible for the improvement of the accounting principles and guidelines already in place, creating positive results for the banking sector in all six member states. However, the findings have some limitations, as the researcher relied on secondary data from 2002–2012, when the financial sector experienced a major crisis in the year 2008. The concentration on Saudi Arabia’s financial market as a benchmark for other GCC member states means that the results might differ if the focus is shifted to another state.

Reference List

Alesina, A.andBarro, R. (2002). ‘Currency unions’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(2), pp. 409-36.

Aljifri, K. (2008). ‘Annual report disclosure in a developing country: the case of the UAE’, Advances in International Accounting,7(6), pp. 45-65.

Aljifri, K. and Khasharmeh, H. (2006). ‘An investigation into the suitability of the international accounting standards to the United Arab Emirates environment’, International Business Review, 15(3), pp. 505-526.

Barth, M. (2008). ‘Fair value accounting: Evidence from investment securities and the market valuation of banks’, Accounting Review,69(5), pp. 1-25.

Barzegari, K. (2010).Value relevance of accounting information in selected Middle East countries. Selangor, Malaysia: University Putra Malaysia.

Beaver, L.(2011). ‘Perspectives on recent capital market research’, Accounting Review, 77(5), pp. 453-474.

Berk, R.(2004). Regressionanalysis: A constructive critique. New York: SAGE.

Blank, K.(2011).Business statistics: For contemporary decision making. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Broadman, J.(2001).Finance and development. New York:SAGE.

Buiter, W.(2008).Economic, political, and institutional prerequisites for monetary union among the members of the Gulf Corporation Council. Washington, DC: CEPR Discussion Paper, 6639.

Callen, T.,Cherif, R., Hasanov, F. and Hegazy, A.(2016).Economic diversification in the GCC: Past, present, and future. Web.

Creswell, J.W. (2009).Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Darrat, A. and Al Shamsi, F.(2005). ‘On the path of integration in the Gulf region’, AppliedEconomics, 37(9), pp. 1005-62.

Dellas, H. and Tavlas, G.(2009). ‘An optimum-currency-area odyssey’,Journal of International Money and Finance, 28(7), pp. 1117-1137.

Dung, N.(2010).Value-relevance of financial statement information: A flexible application of modern theories to the Vietnamese stock market. Vietnam: Saisko Publishers.

Espinoza, R., Prasad, A. and Williams, O.(2010).Regional financial integration in the GCC. Washington, DC: IMF Working Paper No.WP/10/90.

Filip, A.(2010). ‘IFRS and the value relevance of earnings: Evidence from the emerging market of Romania’, International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, 6(6), pp. 191-223.

Filip, A. andRaffournier, B.(2010). ‘The value relevance of earnings in a transition economy: The case of Romania’,The International Journal of Accounting, 45(6), pp. 77-103.

Frankel, J.(2013).The future of the currency union. Washington DC: M-RCBG Faculty Working Paper Series 2010-15.

Frankfort-Nachmias, C. and Nachmias, D.(2008).Research methods in the social sciences. New York: Worth.

Haber, J.(2004).Accounting demystified. New York: American Management Association.

Hamdan, C. (2009).Banking on Islam: A technology perspective. New York: Wiley & Sons.

Hellstrom, K. (2006). ‘The value relevance of financial accounting information in a transitional economy: The case of the Czech Republic’, European Accounting Review, 15(3), pp. 325-349.

Ho, P. (2001).The value relevance of accounting information around the 1997 Asian financial crisis – The case of South Korea. New York: University of Texas at Arlington.

Hung, M.(2001). ‘Accounting standards and value relevance of financial statements: An international analysis’, Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30(3), pp. 401-420.

Jadresic, E.(2010).On a currency for the GCC countries. Washington, DC:IMF Policy Discussion PaperNo. PDP/02/12.

Joshi, K.and Al-Basteki, H.(1999). ‘Development of accounting standards and adoption of IASs: Perceptions of accountants from a developing country’, Asian Review of Accounting,7(2), pp. 23-45.

Joshi, P. and Ramadhan, S.(2002). ‘The adoption of international accounting standards by small and closely held companies: Evidence from Bahrain’, The International Journal of Accounting, 37(3), pp. 429-440.

Laabas, B. andLimam, I.(2002). Are GCC countries ready for currency union? UAE: Arab Planning Institute Working Paper Series No. 0203.

Marat, T. andShoult, A.(2005).‘Doing business with Bahrain: A guide to investment accounting standards to the United Arab Emirates environment’,International Business,37(3), pp. 429-440.

Marquardt, K. andWiedman, M.(2004). ‘The effect of earnings management on the value relevance of accounting information’,Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 31(5), pp. 297-332.

Nakibullah, A. (2011). ‘Monetary policy and performance of the oil-exporting Gulf Cooperation Council countries’,International Journal of Business and Economics, 10(2), pp. 139-157.

Ohlson, J.(2009). ‘Earnings, book values, and dividends in equity valuation’, Contemporary Accounting Research, 11(2), pp. 661-669.

Qystein, K. andFrode, S.(2007).‘The value-relevance of financial reporting’, Financial Review, 15(7), pp. 505-526.

Schaechter, A.(2003). Potential benefits and costs of a common currency for GCC countries, in Fasano, U. (ed.)Monetaryunion among member countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Washington DC: IMF Occasional Paper No.223.

SOCPA (2016).Saudi Arabia accounting standards. Web.

Thinggaarda, F. andDamkierb, J. (2008). ‘Has financial statement information become less relevant? Longitudinal evidence from Denmark’,Scandinavian Journal of Management,3(6), pp. 59-78.

Verbeek, M.(2008).A guide to modern econometrics. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Verriest, A. (2007). ‘The evolution of accounting quality: An international comparison’, The International Journal of Accounting,37(3), pp. 429-440.

Vinod, H.(2008).Hands on intermediate econometrics using R: Templates for extending dozens of practical examples. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishers.

Wang, J. (2010).Business intelligence in economic forecasting: Technologies and techniques. London: IGI Global.

World Bank (2003).The Islamic banking practice in the Middle East. New York: World Bank Publishers.

Zaidi, I.(2010).Monetary coordination among the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. London: IGI Global.