Introduction

Toyota Company is a learning organization. It has created an ideal environment that perfectly tunes all employees’ actions towards the attainment of its goals and objectives. A learning organization offers a place where people actively expand their abilities and capacities to create the most desired outcomes. This process involves nurturing thinking patterns and setting free collective aspirations with the objective of creating an enabling environment where all employees can visualize organizational reality together. In the implementation of these concepts of learning organizations as an important strategy for effective knowledge management, Toyota Company thinks locally but acts globally. In other words, it builds and encourages the sharing of knowledge locally to create products with a global competitive advantage. This paper discusses knowledge management (KM) in the context of DEWA and the Toyota Company.

Distinctive Approaches that Toyota Used to Develop Knowledge Management Practices

Modern organizations face various operational dynamics. Consequently, in a bid to maintain a competitive edge, they must embrace continuous learning as an important strategy for creating a knowledge management system (Rupčić 128). Toyota Company adopted different strategies for developing its knowledge management practices. System thinking was one of such most distinctive approaches. The strategy entailed visualizing the organization as a unit that was comprised of a variety of elements or entities operating separately from each other. The elements were characterized by a hierarchical flow of the voice of command. The main challenge here was how to integrate these entities for them to work harmoniously to enhance organizational success.

Toyota Company recognized the complexity of its small units that formed the entire system in developing its long-term focus on how to amalgamate the components to attain harmony. For instance, at each production level, including the smallest unit being overseen by one employee, the company recognized that the decision made by the worker was imperative for its success around the globe (Toyota Motor Corporation). Consequently, it ensured the development of knowledge that was appropriate for the employee to help in making the ultimate decision of how to run production facilities. For example, by pulling a rope referred to as an Andon, every worker in the production line could bring to a halt the entire production system until the problem is solved. The resolution of a problem involves teamwork to the extent that while GM produces a car in every 34 hours, Toyota takes only 27 hours (Toyota Motor Corporation).

Secondly, Japanese companies, including Toyota, focus on creating knowledge that has enabled them to become innovative. The outcome is the emergence of Toyota Company as a world leader in automobile manufacturing. As opposed to western firms, which focus on explicit knowledge, Ichijo and Kohlbacher (175) observe that Japanese firms such as Toyota emphasize tacit knowledge. Using this approach, Toyota mobilized its employees to learn how to captivate potential customers while at the same time understanding market requirements, which are incorporated into product design up to date. One of the noble knowledge developed by Toyota Company through its tacit knowledge development and management approaches was that the company appreciated customers’ need for flexibility in terms of the choice of products and services in the market. Consequently, a firm should respond by creating products that meet these needs. This situation compelled Toyota Company to deploy the in-house technology and innovation in its practices, which it owes to its knowledgeable employees.

In the deployment of technology and innovation, Toyota Company has designed its production facilities in a manner that they are flexible to accommodate various designs in response to market needs. In other words, Toyota’s production systems can easily switch from one model to another with minimal time and without impairing the quality of its new models. In fact, “By allowing the choice of either people or robots depending upon profitability, the production line offers the flexibility to handle everything from low-volume to mass production” (Toyota Motor Corporation). This extent of innovation permits Toyota Company to use the correct raw materials while ensuring that the products produced are fitted with both accuracy and precision at a minimal cost. People in the production lines are their inspectors. Such delegation is impossible without trust and assurance that employees are highly knowledgeable and can be honesty relied upon in decision-making.

Thirdly, Toyota appreciated the need to tap into its competitors’ knowledge repositories. This distinctive approach to knowledge management led to benefits associated with cross-border strategic alliances, and the formation of foreign partnerships and joint ventures (Ichijo and Kohlbacher 175). The outcome entailed the creation of an inter-organizational learning environment, which fostered knowledge interexchange or transfer. For example, in 2005, Toyota Company established international joint ventures with Peugeot in the Czech Republic (Ichijo and Kohlbacher 173). Under the joint venture, small compact automobiles would be manufactured in an attempt to proactively respond to the changing market dynamics in Europe. In this case, Toyota not only focused on creating knowledge and its transfer to various Japanese-established subsidiaries but also tapped various tacit local staff members’ acquaintances within various foreign markets.

Knowledge Management System at DEWA

Company Overview, Type of KM System, and Its Year of Adoption

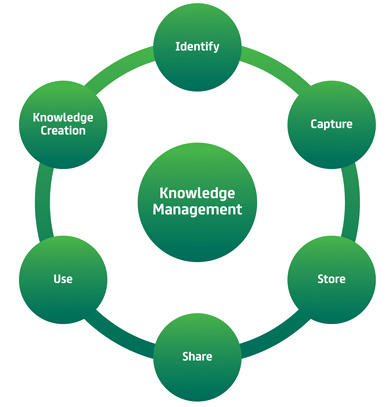

Established in 1992 following late Sheikh Maktoum bin Rashid Al Maktoum’s decree for merging the Water Department of Dubai and the Dubai Electricity Company, DEWA ensures a reliable provision of electricity and water supplies to the people of Dubai. The two institutions had been established in 1959. Before their merging, they had been operating independently. Since the founding of DEWA, it has emerged as one of the leading global companies that provide services to more than seven hundred and sixty thousand customers (Dubai Electricity and Water Authority “DEWA Implements SAP”). By 2015, the company registered a 94% customer satisfaction level. Knowledge management at DEWA requires the possession of capabilities for processing raw data to yield information that can be shared among employees and other stakeholders who include service providers, the government, clients, the public, and partners. The organization began using the knowledge management system, which it calls the KM Cycle from 2009. In 2008, it implemented an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) management information system (MIS). Figure 1 shows DEWA’s KM Cycle.

How the System has Helped to Establish Successful KM Practices

The system selected by the organization has enabled it to establish successful knowledge management practices by providing a framework for identifying, sharing, and capturing knowledge. DEWA has gained substantial industry leadership. It believes that this leadership can only be sustained by building a strong and knowledgeable human resource. DEWA’s ERP system has various tools that have enhanced the capacity to achieve its integrated roles that steer the company’s operations. For instance, it has human resources, financial management, control and monitoring, and customer management functions among others. Indeed, SAP III of its ERP framework focuses on implementing “the institutional asset management and enterprise system in the production, transmission, and water sectors, the fleet asset management and the enterprise system in the business support sector, and the general budget planning system in the finance sector” (Dubai Electricity and Water Authority “DEWA Implements SAP”). The system bears workflow, DMS, business intelligence, and portal modules. Transactional databases have been deployed to help in the storage of logical business transactions.

Just like all organizations that apply integrated information systems, DEWA’s ERP MIS has a transaction database for collecting, updating, processing, and presenting data gathered from business processes (Lecic and Kupusinac 324). The business intelligence platform uses information from DEWA’s databases to create static and/or dynamic reports. IT system technologies such as TREX have helped in indexing various objects to facilitate the display of research results. Workflow entails the different logical processes of executing various business processes in the company without or with minimal human interventions.

Business Objectives that Steered the Implementation of the ERP

The need to establish a knowledgeable team of workers constitutes the main business objective that led to the implementation of a knowledge management system in DEWA. The goal was to boost its performance through quality input from its employees. For instance, in terms of competitive advantage relative to similar companies operating in the United States and Europe, DEWA’s performance has been outstanding. The organization has reduced its power transmission losses by up to 3.3% compared to the U.S. and Europe where the figures stand between 6 and 7 percent (Dubai Electricity and Water Authority “A Continuous Success Story”). While North America records water transmission losses of up to 15 percent, DEWA losses stand at 8.2 percent (Dubai Electricity and Water Authority “A Continuous Success Story”). Indeed, in terms of the minutes lost annually in customer supplies, DEWA emerges as one of the best companies globally. The implementation of an effective information management system and knowledge management systems explains the global leadership of DEWA in its line of business. Hence, the ERP has played a key role in helping the company to achieve its performance and workforce-based objectives.

Challenges in the Implementation of the KM System

In the implementation of knowledge management systems, organizations experience a challenge of attempting to look for new knowledge repositories, which present uncertainties of progressing to an unknown future. However, DEWA had a clear plan for dealing with this challenge. Instead of first focusing on how to build new knowledge, it first considered identifying its existing knowledge through an expert locator and identifying its knowledge assets. This strategy had the benefit of allowing an organization to build experience on how to manage new knowledge effectively in the future (Wheelan 78). For example, through expert locators, DEWA was sure it would prevent knowledge losses by embracing the execution of sequential forecasts and rotation tactics (Dubai Electricity and Water Authority “DEWA Implements SAP”).

Through the strategy, the organization remained sure it would locate experts who could otherwise be lost in the future, thus impairing its capacity to build and share knowledge. The implementation of new KM approaches in an organization interferes with the status quo. Indeed, implementing MIS and KM systems involves change and hence a radical process that alters the operation components of any organization in a bid to achieve some defined objectives and goals (Yukl 56). This situation challenges the status quo. Amid the need for implementing change at DEWA through the KM concept, challenges are inevitable. Indeed, accepting change is not overwhelmingly welcomed by all organizational stakeholders.

Measures to Enhance the Success of the KM System

Resistance to change requires DEWA to adopt different measures for increasing the possibility of success of the knowledge management system. Afonina and Chalupsky support this assertion by observing that change encounters resistance, which requires effective management to enable an organization to flourish within a sophisticated environment (1535). Therefore, to increase the success of the new system, DEWA needs to manage change resistance by benchmarking from its competitors, especially market leaders, including the U.S. and most importantly, the case of Toyota Company. Secondly, it is necessary to evaluate continuously a new system to track all possible bugs that may undermine DEWA’s future success. Considering that DEWA’s operational environment is not static, it needs to update its KM system continuously to ensure that it responds to any emerging changes.

Role of Social Media in Forcing Enterprises to Reconsider Previous KM Approaches

The social media technology enables organizations to improve their efficiency and speed of communicating and executing their objectives, including knowledge sharing. Indeed, Internet connectivity has enabled DEWA to send instant bulk messages to employees and other stakeholders in real-time. Social media also provides room for the direct selling of services online (Cromity 24). Hence, such Internet-enabled platforms constitute important organizational resources that determine the effectiveness of DEWA’s information dissemination. However, its use in the workplace implies making people misuse the resource to realize individual interests such as communicating with friends and relatives, rather than sharing knowledge. Hence, DEWA had to reconsider its approaches to knowledge management to ensure that social media is only utilized to realize corporate benefits.

Employees are not allowed to collect and use corporate information inappropriately through social media. For example, they are under instructions to refrain from collecting information meant for knowledge development and distributing it to competitors against the company’s information disclosure rights. This restriction helps in preventing company-employees conflict. Indeed, the strategy of encouraging the use of social media to achieve the company’s interest increases professional education linkages (Lewis 88). Such networks have the effect of increasing knowledge exchange among people working in different organizations. The exchange fosters innovation, creativity, and the provision of reliable organizational benchmarks (Cromity 28). Where the sharing of information is between customers and employees, social media facilitates the learning of consumers’ needs, which form the basis of developing new product lines.

Conclusion

DEWA, a UAE-based organization responsible for managing electricity and water resources in Dubai, has registered success since its inception in 1992. The organization has become a global industry leader. Part of this success emerged from its focus on building and instilling knowledge in its employees through a KM system that has been in use since 2009. However, such knowledge is impossible to attain without a timely availability of information that forms the company’s knowledge repositories. Benchmarking from other global leaders such as the Toyota Company, DEWA also implemented an ERP MIS system. Building knowledge repositories within an organization require the sharing of organizational information among employees. Nevertheless, employees should exercise due caution not to interfere with the laid down ethical practices, especially with the integration of social media as a channel for sharing knowledge at DEWA. Using social media ethically ensures that DEWA’s resources are only utilized to achieve organizational objectives.

Works Cited

Afonina, Anna, and Vladimír Chalupsky. “The Current Strategic Management Tools and Techniques: The Evidence from Czech Republic.” Economics and Management, vol. 17, no. 4, 2012, pp. 1535-1544.

Cromity, Jamal. “The Impact of Social Media in Review.” New Review of Information Networking, vol. 17, no. 1, 2012, pp. 22-33.

Dubai Electricity and Water Authority. “DEWA Implements SAP – Wave III for Enterprise Resource Planning.” DEWA, Web.

“Dubai Electricity and Water Authority–A Continuous Success Story.” Our History, Web.

Ichijo, Kazuo, and Florian Kohlbacher. “Tapping Tacit Local Knowledge in Emerging Markets- The Toyota Way.” Knowledge Management Research and Practice, vol. 6, no. 3, 2008, pp. 173-186.

Lecic, Dusanka, and Aleksandar Kupusinac. “The Impacts of MIS on Business Decision Making.” TEM Journal, vol. 2, no. 4, 2013, pp. 323-326.

Lewis, Tanya. “Tweeting @ Work: The Use of Social Media in Professional Communication.” Information Services & Use, vol. 34, no. 2, 2014, pp. 88-90.

Rupčić, Nataša. “How to Unlearn and Change–That is the Question!” The Learning Organization, vol. 24, no. 2, 2017, pp. 127-313.

Toyota Motor Corporation. Annual Report 2012, 2012. Web.

Wheelan, Susan. Creating Effective Teams: A Guide for Member and Leaders. Sage Publications, 2013.

Yukl, Gary. Leadership in Organizations. 8th ed., Pearson International, 2012.