Introduction

Globalisation is “reshaping our modes of thinking, ways of behaving and fostering cultural change in societies” (Aguinis, Joo & Gottfredson 2012, p. 385). Some pundits argue that there exists cultural conflict between the various cultures. Nevertheless, it is imperative to note that different cultures may learn from one another and collaborate for the sake of the nation. Presently, there is an emergence of a global culture, which is posing a danger to the survival of national cultures. In 1980, Hofstede came up with a theory that assisted scholars to look at culture from a different perspective. He initiated the idea of cultural values as the core force in molding managerial behaviour. Globalisation has called for a change in how people perceive and understand cultural values. Nowadays, culture is viewed as “having its life full of paradox and change in a dialectical movement” (Covey 2006, p. 11). Globalisation has led to the emergence of an inconsistent progress of cultures. To begin with, the evolving global cultures surpass state borders and national cultures. Then again, “The harmonising power of wireless and internet technology provides local enterprises and native cultural values with unparalleled global coverage” (Aycan, Kanungo & Mendonca 2014, p. 6).

With the knowledge about the effects of globalisation on cross-cultural management, this report seeks to help Windmill Apps to have a clear picture of what their manager expects to find when she goes to work in the Netherlands (Covey 2006). A person may have managerial skills, but fail to achieve organisational objectives due to him or her overlooking the power that cultural values and practices have over businesses. In spite of the Windmill Apps’ manager having an excellent management track record, she might not be able to demonstrate the same in Netherlands due to cultural differences between Netherlands and Indonesia. Hence, the report aims at helping the manager to have a thorough preparation prior to assuming her new role in the Netherlands.

Macro-level facts about Netherlands

The Netherlands practices a monarchy system of leadership. The nation comprises of alliances of numerous political parties. Unlike in the United States where only two major political parties run the country’s politics, in Netherlands all the political alliances play a role in the nation’s politics (Economist Intelligence Unit 2012). The parties encourage business capitalism. They advocate individual economic and political autonomy and conform to financial matters. The Netherlands’ government does not interfere with the country’s economy. The government does not try to manage economic undertakings, and it does not own a vast number of enterprises. What’s more, the government has been attempting to privatise majority of its companies. In spite of the government not taking full control of the country’s economy, it significantly affects economic activities in the country (Gelfand et al. 2012). For instance, the government requires investors to get permits before establishing some businesses.

According to Gelfand et al. (2012, p. 1135), Netherlands’ economic autonomy stands at 74.2 points. This position makes Netherlands’ economy the 15th freest in the world. The country continues to emphasise on business freedom. Netherlands is 6th in economic growth in the European region. Moreover, it is open to the international market. The country’s judicial system safeguards property rights. Therefore, Netherlands is one of the best countries for business.

Value comparison of Indonesia vs. Netherlands

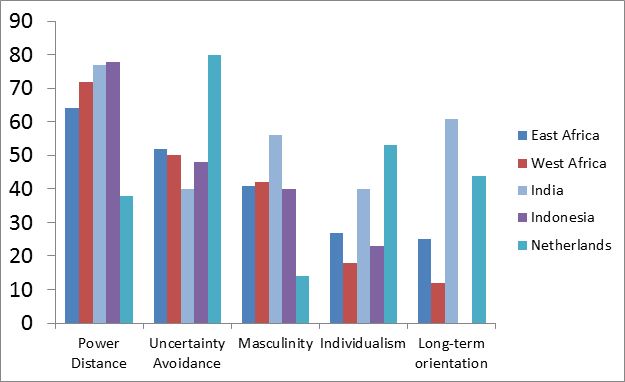

Hofstede analysed national values based on various perspectives. The views included “power distance, individualism, masculinity, pragmatism, indulgence and uncertainty avoidance” (Gelfand et al. 2012, p. 1135). Power distance entails the fact that all people are not equal. It articulates the approach of culture towards these disparities. Netherlands scores poorly in terms of power distance. On the other hand, Indonesia records high. Gelfand et al. allege that the Dutch style is symbolised by “being independent, hierarchy for convenience only, equal rights, superiors accessible, coaching leader, management facilities and empowers” (2012, p. 1134). Leaders encourage their employees to make decisions on matters affecting the organisations. Staff does not like being controlled, and they demand to be consulted at all times. In other words, employees relate to their managers at an informal level. On the other hand, institutions in Indonesia depend on hierarchies where leaders have superior power (Hannay 2008). Additionally, managers have the authority to run and allot duties. Employees expect their leaders to instruct them on what to do in the organisation. The relationship between employees and their leaders is official.

Indonesians embrace a collectivist culture. Hence, the society favours a sturdily defined social structure, in which people are required to comply with the principles of their social groups. What’s more, Indonesians value their families more than anything else. It underlines the reason they prefer staying with their grandparents rather than placing them under foster care. Netherlands embraces an individualistic culture. The country has a loosely-knit social structure, in which people are required to look after themselves and their immediate family members (Hannay 2008). It means that the relationship between workers and their employers depends on mutual benefit. People are recruited and promoted based on their performance.

Uncertainty avoidance looks at how people cope with the fact that it is hard to predict the future. It is hard for individuals to decide whether to seek for mechanisms to control the future or just let nature to take its course. Such a dilemma results to disquiet, and different societies have come up with varied mechanisms for addressing the problem. Netherlands scores high in terms of uncertainty avoidance. It implies that people try all means to curb risks. Netherlands maintains “rigid codes of belief and behaviour and is intolerant of unorthodox behaviour and ideas” (Hannay 2008, p. 8). In Netherlands, it is hard for people to work without regulations. On the other hand, Indonesia scores low in terms of uncertainty avoidance. People in Indonesia prefer “The Javanese culture of separation of internal self from external self” (Hannay 2008, p. 9). It is hard for one to tell when an Indonesian is annoyed since they do not show their anger. Hence, it is hard for managers to understand when their employees are happy and when they are annoyed. Consequently, it is imperative for the managers to enhance workplace relationship. Employees believe in keeping their employers happy since that is the only way that they can be rewarded. Below is a graph of value comparison between Indonesia and Netherlands.

The graph can help the manager to compare the cultural values of Netherlands and Indonesia. In return, the manager would be able to use the right approach in solving disputes and managing the employees in any of the two countries. For instance, in Netherlands, people resist change and innovation. It would be very hard for a manager, who does not have such information to initiate and sustain organisational changes. Consequently, analysing the graph would leave a manager in a better position to cope with the cultural values in the two countries.

Critique of Hofstede’s work

In 1980, Hofstede tried to explain how culture influences business world. His study paved way for experimental analysis of cultural variations and their effects on markets. Hofstede did not only help people to understand the existence of cultural differences, but he also instituted cultural values as core factors in molding managerial behaviour. However, globalisation has led to some of the scholars questioning the credibility of Hofstede’s work. The scholars allege that globalisation does not allow individuals to focus on national culture when analysing business world. Globalisation has made it possible for different cultural values to co-exist within the same society. According to Imai and Gelfand, “human beings, organisations and cultures intrinsically embrace paradoxes for their sheer existence and healthy development” (2010, p. 85). Globalisation has led to the rise of cultural ecology and cultural learning, which have led to the inconsistent changes of cultures.

Decision making

Decision-making process in a multicultural environment depends on the cultural values and practices of the respective cultures. That is, attitudes, values, behavioural pattern and beliefs influence the decision-making process. For states like the Netherlands, which practice an individualistic culture, the leaders are at liberty to make decisions on matters affecting the entire organisation. However, for countries like Indonesia that embrace a collectivist culture, decisions have to be made by consulting all the stakeholders. Failure to consult the stakeholders may result in resistance (Routamaa & Hautala 2008). Consequently, for the managers to make informed decisions, they need to do thorough investigation, establish a number of viable options and evaluate the cultural values that may affect the final determination.

Communication and negotiation

Cultural differences affect communication and negotiation in the business world. For countries that embrace feminism, it is important for managers to communicate with their subordinates prior to deciding on anything. Netherlands and Indonesia practice feminism (Schwartz & Boehnke 2004). Hence, people try to strike a balance between work and private life. In such a case, managers cannot arrive at a constructive decision without having to negotiate with their subordinates. The feminist culture values harmony, impartiality and quality. Hence, it requires the leaders to engage in an extended discussion until all parties are satisfied. In this case, Windmill Apps’ manager might not encounter challenges in making decision since she is acquainted with the feministic culture practiced in Indonesia.

Cultural intelligence

In the contemporary global economy, leadership cannot be perceived only in terms of behavioural and convention standards of the existing culture (Sendjaya & Sarros 2002). Instead, it is crucial to consider novel types of leadership that allow leaders to evaluate individual values and convictions within the background of diverse cultures. Leaders ought to exhibit cultural intelligence. Cultural intelligence is the ability to work in a multicultural environment (Stone, Russell & Patterson 2004). It is the capacity to engender the right behaviour in a novel cultural environment. Globalisation has made country-specific training on cultural value irrelevant. Hence, for a leader to be productive in a multicultural environment, he or she needs to nurture a universal ability to acquire knowledge and change his behaviour based on the prevailing cultural setting. Cultural intelligence is an intrinsic trait that is hard to develop (Walker 2003). Therefore, a leader who demonstrates cultural knowledge is one that can adopt cultural practices based on moral grounds. Such a leader adjusts to varied cultures without compromising his or her convictions and private values.

Conclusion

Globalisation is changing our ways of behaving and promoting cultural changes. Some people believe that globalisation is to blame for the existing culture clash. However, it is important to acknowledge that globalisation has paved way for cross-cultural relations. For leaders to survive in the current global economy, they need to cope with the conflicting cultural practices and to come up with measures to harmonise different cultures. Netherlands and Indonesia differ significantly in terms of cultural values. According to Hofstede’s analysis, Netherlands embraces an individualistic culture, while Indonesia embraces a collectivist culture. On the other hand, the two countries promote feminism. Understanding the disparity in cultural values between Indonesia and Netherlands would help a manager to avert crisis, which might arise due to differences in cultural values between the countries.

Hofstede’s explanation of cultural values overlooks the fact that cultures are not delimited by borders. Consequently, one cannot use states as the core units of cultural analysis. Some scholars have come out to criticise Hofstede’s argument claiming that it does not hold in the contemporary global environment. According to the scholars, a leader ought to have cultural intelligence to cope with the present day business environment. The following are some of the recommendations for dealing with a multicultural business environment.

- Never adopt a cultural value unless it is of significant benefit to the organisation. One needs to be aware of the cultural value, but stick to his or her values.

- Always conduct a thorough research on the social principles of a country or market that you intend to venture. The research is invaluable to business.

- Consult the stakeholders before making critical decisions to avoid resistance.

Reference

Aguinis, H, Joo, H & Gottfredson, R 2012, ‘Performance management universals: Thinking globally and act locally’, Business Horizon, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 385-392.

Aycan, Z, Kanungo, R & Mendonca, M 2014, Organizations and Management in Cross-Cultural Context, Sage Publications Ltd, London.

Covey, S 2006, ‘Servant leadership: Use your voice to serve others’, Leadership Excellence, vol. 23, no. 12, pp. 5-16.

Economist Intelligence Unit 2012, competing across borders how cultural and communication barriers affect business, Web.

Gelfand, M, Leslie, L, Keller, K & Dreu, C 2012, ‘Conflict cultures in organizations: How leaders shape conflict cultures and their organizational-level consequences’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 97, no. 6, pp. 1131-1147.

Hannay, M 2008, ‘The cross-cultural leader: the application of servant leadership theory in the international context’, Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1-12.

Imai, L & Gelfand, M 2010, ‘The culturally intelligent negotiator: the impact of cultural intelligence (CQ) on negotiation sequences and outcomes’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 112, no. 1, pp. 83-98.

Routamaa, V & Hautala, T 2008, ‘Understanding cultural differences the values in a cross-cultural context’, International Review of Business Research Papers, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 129-137.

Schwartz, S & Boehnke, K 2004, ‘Evaluating the structure of human values with confirmatory factor analysis’, Journal of Research in Personality, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 230-255.

Sendjaya, S & Sarros, J 2002, ‘Servant leadership: Its origin, development, and application in organizations’, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 57-64.

Stone, A, Russell, R & Patterson, K 2004, ‘Transformational versus servant leadership: A difference in leader focus’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 349-361.

Walker, J 2003, ‘A new call to stewardship and servant leadership’, Nonprofit World, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 25-33.