Abstract

Supply chain management has traditionally been concerned with companies as theoretical constructs that always take the most rational route of action. However, this view is becoming insufficient as it becomes apparent that the human factor plays a significant role in company decision-making. The sub-discipline of behavioral supply chain management was created to address this aspect of the job. This dissertation is a systematic literature review that aims to determine the primary issues addressed by behavioral supply chain management and the approaches that have been developed to address them. It analyses 107 recent works from various scholarly journals and conferences to identify the foremost current trends in the discipline.

Introduction

In the modern environment, it is easier for companies to cooperate with distant companies than ever before. It is easy to discuss deals and seal contracts with distant companies using modern communication technology. As such, logistically complex supply chains arise much more frequently than they did before, with the difficulties associated with operating them. The need for reliable cooperation methods between different companies emerged. The insufficiency of traditional models, which assume that companies operate perfectly rationally, led to the creation of behavioral supply chain management as a separate discipline (Zsidisin and Henke 2019). People operate the supply chain and often act based on feelings over logic, and it is possible to apply the same or similar methods to improve their efficiency as in internal management (Donohue, Katok, and Leider 2019). The authors further claim that companies cannot ignore the competitive advantage offered by efficient and reliable practices that result from the use of such detailed supply chain management approaches.

Research Rationale

While more and more firms and researchers are recognizing the importance of behavior in supply chain management, the field is still mostly unexplored. Managers adopt various approaches that sometimes succeed, but it is possible to observe a lack of concerted scholarly effort to codify the central aspects of behavioral supply chain management and the appropriate methods for addressing them. As such, publications on the topic are relatively few compared to the overall scope of the SCM field. The lack of organization and resources invested in the development of the field complicates the task of investigating various factors for researchers. It also makes it harder for managers to integrate the latest findings, as they are not widespread. A central framework that lists contemporary issues and various possible solutions for them would be beneficial for both parties.

Research Problem

While supply chain management as a whole has existed for a long time, most researchers focus on its organizational aspect (Schorsch, Wallenburg, and Wieland 2017). They review companies as monolithic entities that operate purely from considerations of profit in both the short and the long term. While such an assumption can make analysis and predictions easier by restricting the courses of action that each entity in the model may take, it can be inaccurate. Depending on the management, companies can take action that prioritizes specific values at the expense of others (Reuter et al. 2017). For example, a supplier may be uncomfortable with sharing its technology, even if doing so would enable better integration and higher efficiency. As such, it is in the best interests of the buyer to ensure the integration, but the traditional supply chain management theory does not provide a solution to the issue. However, behavioral supply chain management may be able to resolve the situation satisfactorily for both parties, and so it warrants an investigation.

Aims and Objectives

This paper aims to create an overview of the current state of the behavioral supply chain management literature. The field is continuously evolving due to its young age, and so its core elements have not been codified yet, leading to slow growth as researchers struggle to find a beginning point. This dissertation will take a step towards rectifying the lack by reviewing current literature in the field and summarizing its findings. It will describe the foremost issues that are currently being researched in the behavioral context and identify their influence on companies’ everyday operations and supply chain management methods. It will also describe the approaches that are being recommended as useful by managers and scholars. The goal of the study is to define prominent future research directions as well as areas supply chain managers may want to address.

Methodology

Behavioral supply chain management is still somewhat new, and the research body for this aspect of the discipline is small compared to its overall size and scattered throughout a variety of publications. As such, this study will be a systematic literature review, which is appropriate for the context and has proven itself useful in supply chain management applications (Durach, Kembro, and Wieland 2017). The question that directed the analysis was:

- What components constitute the behavioral aspect of supply chain management?

- How do they affect the operations of the system?

- What management methods can be employed to address concerns and take advantage of strengths?

Each topic required a significant amount of supporting evidence that would cover a variety of perspectives and introduce the latest concepts in the field.

Articles were selected based on a set of explicit criteria to ensure maximum objectivity and analyzed thoroughly. The databases used for the search included JSTOR, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar, as all three contain a significant amount of scholarly research on supply chain management. From the initial selection of approximately 16,000 recent articles published in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings, 106 passed selection procedures and were used in the review. The first collection included 15 papers that would be used to provide a general overview of the topics that would be investigated in the paper. These papers contained specific keywords that defined their field, which was then used to search for articles that discussed various aspects of the same issue. As the goal of this investigation was to create a comprehensive overview, papers with overly similar topics to ones already selected were discarded. Lastly, a significant portion of the works located in the database was rejected due to time constraints, which did not permit an investigation of all candidates with the existing resources.

Literature Review

The literature review discovered five primary issues that can arise when the behavioral aspect of supply chain management is neglected. Boonjing, Chanvarasuth, and Lertwongsatien (2015) identify them as “management methods, power and leadership structure, risk and reward structure, culture/attitude, and trust/commitment” (p. 556). de Abreu and Alcântara (2015) note that the profile of a supply chain manager is not yet well defined, and the people who occupy the position may struggle with acquiring and using necessary competencies, leading to inefficient management. Furthermore, according to Donato and Shee (2015), many supply chain relationships are short-term and not well established, leading to an imbalanced power structure where one side dominates the contract. While the arrangement benefits one party in the short term, the other suffers damage, creating an unsustainable and volatile model where there are ultimately no winners.

Unstable environments force supply chain members to consider the risks and rewards of partnering with another company to determine whether the action is desirable. Monroe, Teets, and Martin (2014) discuss five categories of potential risks, including ones coming from the sides of supply and demand as well as process, control, and environmental issues. As such, Chinomona and Hove (2015) note that suppliers who are not involved in the firm’s operations can decide to end the relationship to avoid these risks, necessitating a rearrangement of the chain. Situm and Mateos (2017) note that many managers are also concerned about disruptions, which can have severe adverse effects on a company’s performance in the current market. As such, behavioral factors play a significant part in the establishment of a sustainable supply chain, which has to take place before the network is reinforced and enhanced in terms of value.

The adoption of a comprehensive and modern approach to supply chain management is an organizational effort, and employees have to commit to the implementation of the practices. As such, Parmar and Shah (2016) identify weakly or lacking corporate culture as a significant barrier to the establishment of robust and efficient supply chains. Additionally, supply chain optimization requires the close cooperation of two or more companies, with each taking a significant role in the internal operations of its partner to identify deficiencies and suggest improvements. As such, mutual trust is essential to successful partnerships, but, as Daudi, Hauge, and Thoben (2016) state, its nature changes throughout the relationship, and its inconstant nature should be taken into account. As such, all five areas present potential issues or improvement opportunities based on human decisions and attitudes, and behavioral supply chain management emerged in response to the growing importance of this area.

The management methods necessary to address the behavioral aspect of supply chain organizations are mostly similar to those required of traditional managers. Krishnapriya and Baral (2014) discuss the essential competencies necessary to manage human resources for the creation of a successful supply chain. Nimeh, Abdallah, and Sweis (2018) discuss the applicability of established lean principles and the elimination of waste to supply chains. However, a manager cannot coordinate the activities of another company directly, even if that firm is a supply chain partner. As such, he or she should exhibit leadership that would push the supplier to adopt optimal practices, with transformational leadership being the best approach to the task (Birasnav, Mittal, and Loughlin 2015). The firms’ operating efficiency would be enhanced as a result, and the supply chain management would achieve its goals and become able to pursue further targets.

The risks associated with supply chain partnerships should be minimized on both sides to ensure that the participants choose to prolong their relationship and expand it by engaging in further ventures and integrating closer. Ho, Zheng, Yildiz, and Talluri (2015) provide a comprehensive overview of risk management methods developed throughout the early 21st century that can be used to create a basic framework and expand it as new studies and approaches the surface. Schöttle, Haghsheno, and Gehbauer (2014) suggest that organizational culture should be adjusted to one of cooperation and collaboration to achieve supply chain success. Avota, McFadzean, and Peiseniece (2015) discuss how personal and organizational values can be linked to corporate sustainability, particularly about supply chains. Lastly, Willette, Teng, and Singh (2016) propose the formation of a trusting and collaborative relationship between supply chain members through the use of a shared IT system. By integrating its processes with those of the suppliers, the firm creates a guarantee of loyalty and reliability, building trust and enabling the continuation of the process.

Importance of Behaviour in Supply Chains

As can be seen from the review above, behavior can affect many, if not all, aspects of supply chain relationships. Suppliers may refuse to engage in relationships altogether because of potentially irrational management decisions. Current strategic partners may refuse integration initiatives from the company even though they should be beneficial to both sides. Without understanding the behavioral aspect of decision-making, it can be challenging to discern the reasons behind these refusals. For example, different managers may view the same risk as either worth taking or too high compared to the potential profit (Wuttke, Donohue, and Siemsen 2018). However, if this perception is changed using one of a variety of techniques, they will be ready to cooperate and create value for both companies. The possibility of turning such failures into successes through minimal resource investment is the primary appeal of behavioral supply chain management.

Primary Factors

Management Methods

Supply chain managers are responsible for the operation of the corresponding department as well as negotiations with current and potential suppliers. As such, part of their job is to assign workers to positions where they can achieve the most good and motivate them to work (Boonjing, Chanvarasuth, and Lertwongsatien 2015). As such, the supply chain manager must choose the appropriate management method for the company and the situation. In addition to theoretical knowledge, the approach may require other competencies. This section will discuss management methods in supply chain operations and related aspects.

Any supply chain manager should still have the essential competencies of his or her profession, including the ability to organize employees to achieve excellent outcomes. Bon, Zaid, and Jaaron (2018) point out the importance of human resources to supply chain management practices to create a sustainable framework. Regardless of the degree of planning and strategic sophistication employed at the company, it cannot succeed without a staff that is capable, competent, and well-organized for its purposes. In particular, Gupta and Singh (2015) describe employee relations and training as the primary factors that affect the supply chain, with safety, risk management, and attitude being secondary. A manager should be capable of ensuring that these concerns receive appropriate attention and display general competence in matters such as assigning people positions that suit their skills.

Emotional intelligence, a concept that is gaining popularity in many management environments, is a significant part of good employee relations. According to Suifan, Abdallah, and Sweis (2015), high values in the manager’s various indicators of the trait correlate to excellent employee work outcomes, and the results can likely apply to supply chain management, as well. Training can help employees navigate the unfamiliar environment of asymmetric inter-organization negotiations and collaboration better, improving their performance and that of the company. According to Bust, Finneran, Hartley, and Gibb (2014), safety is a significant part of the training in some industries that rely on supply chains heavily, such as construction and food production. Risk management and attitude will be discussed in a different section, as they have to be part of a global risk management framework and an organizational culture change, respectively.

Managers should be aware of current paradigms and incorporate them into their approaches to organizing the firm’s supply chains. Bortolini, Ferrari, Galizia, and Mora (2016) discuss the application of lean and green principles in supply chain management to reduce the amount of wasted effort and resources while achieving reductions in the pollution generated by the manufacturing process. The outsourcing of environmentally harmful processes to another company does not remove a firm’s responsibility for contributing to existing issues. Furthermore, Suryanto, Haseeb, and Nartani (2018) suggest that the application of green practices may improve a company’s performance. Methods with less pollution tend to be more efficient, and detailed audits into the operations of various members of the supply chain are likely to discover issues and fix them throughout the process of improvement.

Power and Leadership Structure

Most relationships between companies tend to happen on uneven grounds, and the company that is in the weaker position will likely be unhappy with the state of affairs. Boonjing, Chanvarasuth, and Lertwongsatien (2015) claim that both strength and weakness can affect a company’s commitment to the relationship. However, a single company usually cannot change the state of the market, and so supply chain managers have to learn to operate in their current environment. This section will describe the main theoretical findings of the literature on the topic, and the practical implications of potential issues will be described in the next chapter.

The relationship between suppliers and buyers tends to be complicated, with the market dictating the direction of the power and the dependence of members on each other. Huo, Flynn, and Zhao (2017) discuss various factors that can affect interactions, such as dependence asymmetry, mutual dependence, power type differential, and power source asymmetry, and their influence on performance. A dominant firm will benefit strongly from the relationship, but its partners may suffer as a consequence due to their inability to achieve advantageous terms. Khoja et al. (2015) claim that the imbalance cannot be eliminated, and supply chain members have to learn to trust each other and collaborate in an unequal environment without entering conflicts that reduce their performance. A firm has to be able to create a profitable relationship without disincentivizing its partners from future cooperation with unfavorable terms.

Depending on the market type, either suppliers or buyers (or neither) can dominate, and the specific power structure tends to be determined by the nature of the industry. Gallage and Endagamage (2016) discuss how powerful buyers who are small in number can impose a variety of requirements on suppliers, who do not have access to other distribution channels and are therefore forced to comply. Similarly, suppliers who operate in advantageous conditions can make their buyers pay higher prices or accept otherwise unfavorable terms. However, He, Ghobadian, and Gallear (2016) note that regardless of who holds power, relationships, where it is exploited, are unproductive, though relationships, where one side has a stable advantage and uses it, can become lasting and synergetic. Nevertheless, firms should take measures to address power imbalances and ensure that synergy takes place instead of conflicts.

The situation becomes more complicated when multi-layer supply chains are taken into account, as in such a structure, some companies will have to procure resources from suppliers while also satisfying buyers down the supply chain. Wilhelm, Blome, Bhakoo, and Paulraj (2016) discuss how independent monitoring of all of a company’s suppliers is a challenging task, and many firms have to rely on first-tier suppliers to ensure that their supply chain relationships are profitable and sustainable. Power structures in such environments can develop in unique and unpredictable ways, especially if the end buyer decides to become involved in the management process. Reuter, Franke, Kirchoff, and Foerstl (2017) discuss how in triadic situations, firms can cooperate, compete, do both at the same time, or form a two-firm alliance against the third. The complexities of multilayer environments make the task of the supply chain manager complicated and challenging.

Risk and Reward Structure

In a supply chain relationship, the buyer relies on the supplier to produce and deliver sufficient amounts of a good when it is necessary. The supplier requires the buyer to secure sufficient sales to pay for the goods delivered. As such, both sides take risks when committing to a relationship in expectation of a sufficient reward to justify them. If one of the parties is not satisfied with the proportion of risk to reward, they will likely want to end the relationship eventually (Boonjing, Chanvarasuth, and Lertwongsatien 2015). It is possible that behavioral supply chain management can offer an answer for the concern. However, an analysis of the pertinent issues is necessary to determine whether this is the case, and this section will be devoted to it.

Cooperation is essential to the success of a supply chain network, as various members will be able to accommodate the needs of each other better with closer interactions. According to Duhamel, Carbone, and Moatti (2016), collaborative relationships can significantly improve a company’s risk management practices. However, in the environment of supply chain management with its volatile and asymmetric power structures, firms may want to maintain a distance in relationships. Khan, Qianli, and Zhang (2017) note that such dictatorial links can damage the entire chain once the supplier and buyer become adversaries and take measures to reduce each other’s power. As such, close relationships present a risk, especially for smaller suppliers, who are unlikely to have significant influence. They are then inclined to avoid cooperating with their partners, a trend that can express itself through several avenues.

A lack of resource sharing is the most prominent issue that is associated with weak cooperation. Gao, Li, and Kang (2018) define the knowledge, information, and revenue as the foremost resources that should be distributed along the chain to improve performance. However, a distrustful firm may want to minimize such interactions and maintain a seller-buyer relationship. Ambilikumar, Bhasi, and Madhu (2016) state that the information-sharing behavior associated with such a practice, one where orders between two neighboring supply chain members are the only information shared, is ineffective compared to a variety of other models. They also describe this inferior model as traditional, implying that many companies still employ the practice depending on the nature of their purchases. As such, companies should encourage resource sharing, but a closely collaborative relationship has to exist before the use of knowledge or revenue sharing.

To promote close collaboration, a company has to provide its supply chain partners with offers of sufficient rewards to offset the risk. On its own, a partnership offers a variety of benefits such as increased responsiveness, competitiveness, and the reduction of waste (Yi, Jamal, and Chin, 2016). However, many of these improvements are likely experienced by the buyer to a higher degree than the suppliers. As such, they may not be sufficient to override concerns about the exploitation of power by the company that holds power in the relationship. Shahzad, Takala, Helo, and Ali (2016) suggest the use of economic governance mechanism to increase the symmetry in the relationship and improve the commitment of all members. Managers should investigate the approach and determine its viability in regards to addressing the concerns of potentially uncertain supply partners.

Culture and Attitude

The manager is not the only person who will interact with the supplier or be responsible for making supply chain decisions. Furthermore, trustworthiness may be an issue with unknown suppliers, and the wrong choice can lead to fraud and failure in meeting expectations. However, Boonjing, Chanvarasuth, and Lertwongsatien (2015) claim that by creating appropriate organizational culture and attitude, companies may be able to understand their understanding of other supply chain members. As such, supply chain managers should understand how to change the culture of their company as well as its suppliers. This section will discuss current issues and the potential benefits of cultural adjustments.

Various members of the supply chain should be aligned towards the same goal for optimal efficiency and performance. According to Porter (2019), flexible organizational cultures help various firms organize in a supply chain framework that improves their performance. When suppliers and buyers have similar goals and methods, they will likely find cooperation more comfortable and more productive (Porter 2019). They will also enhance their capability to attract new supply chain members when a need for a particular resource arises. Hamid, Elhakem, and Ibrahim (2017) highlight compatibility, commitment, and credibility as vital traits that help improve a firm’s operational adaptability. The attribute is critical in the modern environment, where competition is intense, and new products and needs emerge continuously. The company may frequently need to significantly adjust its products or introduce new ones, which will likely require suppliers to do the same.

Many companies are concerned with sustainability as much as with development and improvement, if not more so. According to Tay et al. (2015), organizational culture is a significant contributor to the establishment of a lasting supply chain relationship alongside employee involvement and top management commitment. Conversely, mismanaged cultures can become barriers to integration and reduce the system’s operating capacities. Furthermore, supply chain members cannot be satisfied solely with internal investigations and should ensure that everyone in the structure follows basic proper business guidelines. As Bhatia (2018) states, while an environment of integrity and honesty within the organization is achievable without much difficulty, the situation is different with regards to suppliers, especially those removed several tiers. A supply chain manager needs to understand the methods he or she can use to influence the cultures of the company’s partners and their associates.

Aligned goals and values are also essential to the introduction of practices such as corporate social responsibility. Hyder, Chowdhury, and Sundström (2017) note that collaboration in such practices is only possible when the company can be assured that its suppliers will participate competently. If the organization engages in corporate social responsibility practices, but its suppliers do not, the negative connotations of the latter’s methods may affect the buyer, negating the effects. According to Srivastav and Gaur (2015), organizational culture is a significant barrier in the adoption of green supply chain management practices for small enterprises, as firms feel pressured to ignore the environment and focus on reducing costs and improving the product quality. As such, a redefinition of their goals and values is necessary before the process of creating an environmentally friendly manufacturing process can begin.

Trust and Commitment

Trust is critical to supply chain relationships, though it is not the sole requirement for their success. According to Boonjing, Chanvarasuth, and Lertwongsatien (2015), high trust can increase collaboration and information sharing between partners. Conversely, a company that distrusts its buyers or suppliers may be reluctant to engage in any such initiatives despite the potential for financial gain. As such, supply chain managers should be able to understand how to foster trust with other supply chain members and ensure that they commit to the relationship. This section discusses the nature of trust and potential issues that can arise from its lack of presence.

A company is less likely to engage in close partnerships with another entity if it does not believe the other to have the interests of both parties in mind. Brinkhoff, Özer, and Sargut (2015) conclude that trust is necessary for the success of a supply chain management project, even if it is not sufficient for the purpose without additional factors. It is critical for the partnership to begin, as both organizations have to believe that they will benefit from the relationship. Trust is also vital if one or both members intend to involve themselves in the other’s operations. Shubhansh and Acharyulu (2017) note that trust is more important than power in supply chain integration activities that enhance performance. If one partner tries to force the other into a close relationship, the resulting improvements will not be optimal and will possibly lead to the dissolution of the partnership.

Trust is also critical for the creation of lasting relationships, ones where a partner will not eventually determine that leaving is the best course of action for the company. According to Gupta, Choudhary, and Alam (2014), organizations that trust their suppliers tend to keep their best interests in mind and aim to create lasting relationships. Conversely, suppliers try to be flexible and honor commitments when the buyer changes its requirements on short notice. This consideration is particularly relevant to situations where demand is unstable, and the relationship is potentially damaging to the supplier. Nur Prima Waluyowati and Djumahir (2018) highlight the importance of this trait to small and medium enterprises, which can obtain lower prices from committed relationships and often have to change their order sizes. Without trust, supply chain partners would abandon them as too risky and unprofitable, making growth and continued operation extremely challenging.

It should be noted that the implications of trust are not entirely positive, as there is usually no way to ascertain that it is mutual. Martins et al. (2017) note that buyers tend to trust suppliers more than vice versa, enabling opportunistic behavior and ultimately undermining productivity. This tendency opposes traditional theory, which postulates that trust fosters positive cooperation and an overall improvement in supply chain performance. However, the human factor sometimes overrides such considerations, particularly in countries where managers are not familiar with the latest theory. Anin, Essuman, and Sarpong (2016) note that opportunistic behavior is typical in contexts where asymmetries give advantage to some party, even though they reduce overall organizational performance. Supply chain managers should consider these matters and understand that various philosophies of business exist with some being capable of harming a company’s supply chain partners.

Importance and Influence

Management Methods

Proper management of human resources is essential to the proper operation of any enterprise or business activity, including supply chain transactions. Marwah, Jain, and Thakar (2014) highlight the notion that employee and management involvement contributes heavily to the overall performance of the supply chain. Committed, well-managed employees will perform their duties better, resulting in general improvements in every operation involved in the process. These changes are reflected in several variables that are valuable indicators of supply chain success and the ability to respond to threats, such as agility, flexibility, and performance. In the study conducted by Garcia-Alcaraz et al. (2017), human resource skills and capabilities have a significant positive correlation with all three of the parameters mentioned. As such, supply chain managers cannot neglect their immediate subordinates, even if their job involves high amounts of external interactions.

Emotional intelligence is among the essential competencies for any manager who intends to deal with the behavioral aspects of the profession. Subramanian (2016) claims that the skillset is among the managerial traits that are in the highest demand in the managerial marketplace. A supply chain manager can use it to organize his or her subordinates better while also understanding the motivations and intentions of the company’s suppliers better. Emotional intelligence is particularly relevant with regards to initiatives that affect the entire supply chain and are more beneficial for the buyer than the suppliers. Aziz, Mahadi, and Baskaran (2017) state that the trait is critical in convincing employees to adopt environmentally friendly practices. The same tendency is likely real for supply chain partners, particularly in cases of close integration and cooperation.

Other aspects, such as general business intelligence, are capable of considerably enhancing the performance of the supply chain when applied by a competent manager. Pool et al. (2018) state that business intelligence adoption is capable of improving the system’s agility considerably, leading to improved speed and quality in its decision making. As such, the supply chain will be more sustainable and capable of handling threats and issues due to its improved organization. Besides, the successful implementation of socially and environmentally responsible practices can improve the firm’s performance. Tan et al. (2016) state that green supply chain management approaches can improve a firm’s competitiveness by improving the efficiency of the entire framework. However, corporate social responsibility is still a developing topic, and managers have to observe it to determine the full scope of the potential benefits.

Power and Leadership Structure

Power asymmetries generally lead to adverse outcomes in supply chains, as companies are likely to use them for their benefit at the expense of their partners. As Guillen and Franquesa (2015) show, both the suppliers and the consumers can suffer as a result, with the former receiving low payments and the latter having to deal with high prices regardless. Due to the antecedents of power asymmetries, the suppliers will likely not be able to escape the relationship, entering a period of continued low performance. They would then have to resort to various cost-saving measures to remain profitable and possibly overturn the dynamic. Sundström et al. (2016) note that economic difficulties force suppliers to use irresponsible subcontractors and ignore CSR improvement initiatives that come from the buyer. As a result, the buyer can experience the adverse influence of power asymmetry even while benefiting from it.

A weak position in the relationship can also interfere with the integration between firms, particularly about resource sharing. Dao and Napier (2015) note that the organization that owns knowledge will be primarily responsible for creating the transfer process, forcing it on the other firm if it is dominant. Conversely, it may be reluctant to share its technology if it is the weaker partner, and the buyer will have to employ active measures to ensure that the integration happens. However, such actions are likely to reduce the supplier’s satisfaction and potentially lead to the dissolution of the relationship. Afolayan, White, and Mason-Jones (2016) note that knowledge acquisition is among the most critical roles of the supply manager. As such, the abuse of asymmetric relationships is contrary to the profession’s purpose and goals.

Lastly, power asymmetries can have considerable effects on impending innovation due to the lack of interest in information sharing exhibited by the weaker side. Michalski, Yurov, and Botella (2014) claim that the state has a negative influence on IT innovation in both mature and emerging markets, leading to reduced organizational performance. Fears of opportunistic behavior by a firm’s supply chain partners are often cited as the reason for the resistance to collaboration. With that said, close cooperation may not necessarily be the optimal method of developing innovations in supply chains. Wang and Liu (2016) describe sequential change as the optimal choice of strategy in a non-symmetrical market, though cooperation remains superior in an equal relationship. Asymmetries are often challenging or impossible to eliminate, and supply chain managers should take the fact into account and devise alternate approaches.

Risk and Reward Structure

In many industries, supply chain risks can carry massive consequences, including industry changes on the global scale or loss of human life. Vishnu and Sridharan (2016) describe how natural disasters made Toyota lose its leading position in the automotive industry and disrupted food supply chains, where errors can lead to criminal responsibility and death penalties. Both the buyer and the supplier can take severe damage from a supply chain failure, and so the risks are massive. External factors are not the only reason why industry may be risky to enter and operate in, as many markets are volatile by nature. Martino et al. (2017) provide the example of the fashion industry, where trends change constantly and unpredictably, leading to a variety of risks for a typical producer that sources various materials and supplies clothing to a variety of retailers. As such, companies may not be willing to enter such dangerous environments, with fabric producers choosing to work with furniture producers or other industries that will use their products.

Innovation is a particularly significant risk, as it may remove the need for a particular supplier and leave the company without a buyer or future perspectives. Mohr and Khan (2015) discuss 3D printing as one such phenomenon, as the technology will potentially enable the production of products by any entity with the proper equipment without the need to source components, reducing costs by a large margin. As such, it can eliminate the need for many supply companies, especially distant ones, particularly if the buyer has access to their technology from the close partnership and can replicate it using the printer. However, overall, such a change would present an improvement for the buyer, and so innovation is a mechanism with both advantages and risks. Li and Li (2017) note that Internet of Things changes can present potential risks but also improve security if appropriately managed. As such, the topic is complex and has a discipline dedicated to it that has generated a large body of research.

On the other hand, a high reward for cooperation is likely to spur potential partners to provide excellent terms to secure the firm’s participation and improve general performance. Venkatesh et al. (2015) note that a sustainable supplier has a strong basis for negotiations with other companies and can offer suggestions for process improvements that they would then carry out. Sustainability is highly desirable in supply chain management, and partners would want to maintain the relationship to continue to avoid disruptions. There are also indirect benefits to supply chain sustainability that may not be immediately apparent without prior investigations. Xu and Gursoy (2015) discuss how sustainable hospitality supply chain management improves customer attitude, behaviors, and willingness to pay a premium. As such, high-reward partnerships influence every member of the chain positively, leading to significant benefits overall.

Culture and Attitude

The internal culture of an organization can influence both the creation of new supply chains and the maintenance of existing ones considerably. Vankireddy and Baral (2019) identify information sharing, particularly its cross-functional aspect, participative culture, and a learning orientation is essential for integration. These traits are required of all employees, not just the manager himself or herself, and so can demand considerable change from the firm. However, if these requirements are not met, there is a possibility that issues will surface and interfere with the project’s progress. Akafia, Muntaka, and Boahen (2017) discuss the implementation of a new element of the supply chain that was complicated by factors such as a lack of trust within the organization, a short-term orientation, and a lack of leadership that was compounded by an inappropriate power structure. Employees were not motivated to try and implement the initiative because the management could not provide adequate incentives.

The recognition of sustainability as an essential part of supply chain management methodology is recent, though the concept has existed for a long time. Morais and Silvestre (2017) claim that a unified approach to the topic does not exist yet, and so companies that try to address the concern employ various strategies and achieve a diverse array of outcomes. Some of these results can be interpreted as a partial or complete success, and so the approaches taken by entities that have achieved them warrant investigation. It should also be noted that sustainability is a growing concern for the public, especially in critical sectors such as the food production industry. Topp-Becker and Ellis (2017) claim that the reporting conducted by agricultural companies is insufficient, and more firms should engage in it while covering aspects other than environmental impacts. Overall, businesses should concern themselves with long-term goals and supply chain sustainability to improve their performance.

Corporate social responsibility plays a similar role to sustainability and achieves many of the same outcomes, particularly with regards to company image and long-term success. Hakim et al. (2017) state that many multinational corporations are under pressure to control the CSR practices of their supply chain members. The entire supply chain is perceived as a single entity, and so the poor performance of one member is seen as the failing of the whole system, with the company that interacts with customers directly being affected the most. Furthermore, the blame may be partially justified, as large companies should have the capability to influence their partners and make them adopt responsible practices. Kempa et al. (2018) identify organizational culture as a significant driver for corporate social responsibility in an enterprise and its supply chain. As such, the adjustment of a company’s practices is essential for the improvement of its supply chain.

Trust and Commitment

Trust is essential to collaboration, as companies should be willing to cooperate and interested in making the relationship succeed to achieve the best results. Ke et al. (2015) claim that both formal, contract-based supply chain relationships and informal, trust-based efforts are critical for improving a project’s performance. Trust without sufficient contractual safeguards can lead to one party exploiting the relationship, and contracts without trust may lead one of the sides to refuse to extend their durations. However, when both aspects are satisfied, and two organizations collaborate entirely, they can produce unexpectedly high results. Simatupang and Sridharan (2018) attribute this effect to the existence of a considerable number of variables that only surface when both sides actively look for improvements. As such, the creation of commitment is essential for the enhancement of a supply chain’s performance.

Knowledge sharing is one particularly crucial trust-related factor that can enhance the performance of all supply chain members. Tian (2018) describes it as one of the reasons why enterprise performance improves as its supply chain begins collaborating more closely. When companies have access to each other’s technology and information, they can adapt to their partners’ needs more easily and quickly and possibly offer improvements over their existing solutions. In general, the sharing of various resources, including information and knowledge, between supply chain members can significantly improve efficiency. According to Gong, Liu, and Lu (2015), the approach significantly reduces the time required to achieve the same results, eliminates a large portion of losses, and is superior in most other aspects to resource exclusivity, as well. However, the practice is not possible if member companies do not trust each other due to a variety of fears.

Lastly, trust can influence the incidence of the bullwhip effect, wherein mismatches between demand forecasts and their actual values have increasingly strong effects as the information moves up the supply chain. de Almeida et al. (2017) claim that both affective trust and trust in the competence of the partner are essential for the mitigation of the phenomenon, though it cannot be avoided entirely. The shared knowledge and information can help companies formulate more accurate forecasts and reduce the overall disparity with reality. Furthermore, an increased trust will reduce the need for companies to request more units than is necessary to cover potential risks, reducing the burden on suppliers. Igwe, Robert, and Chukwu (2016) provide an example of how improved trust reduced the bullwhip effect and improved a company’s on-time delivery. As such, companies should consider enhancing their relationships with suppliers as an avenue for improvement.

Improvement Methods

Management Approaches

Supply chain managers should learn how to manage both their employees and their relationships with other companies to maximize trust and achieve optimal results. Many possible methods and techniques can apply to the situation, such as changing nuances in contract design (Wuttke, Donohue, and Siemsen 2018). Managers should aim to create specific traits in the organization, as well. While the achievement of some of these goals may not strictly be related to behavioral supply chain management, the effects they generate can resolve some of the issues highlighted in the discipline. As such, this section discusses possible solutions and methods that can be used for their implementation.

The emergence of the human factor as a prominent determinant in the supply chain relationship necessitates the creation of a supply chain management branch that is devoted to analyzing and addressing its influence. Shorsch, Wallenburg, and Wieland (2017) claim that while behavioral supply chain management is growing, it is still small compared to its parent discipline and not sufficiently developed to answer every question. Further research and development are necessary to assess the entire scope of human behavior with regards to efficient operation and implementation of initiatives. Nevertheless, many companies and researchers are beginning to consider the topic in their analyses of critical issues. For example, Kole and Sarode (2016) discuss behavioral factors and their influence on green supply chain management, which is vital in the current context of corporate social responsibility. As such, every measure that can influence the process deserves consideration and, possibly, application.

Behavioral approaches should be integrated into supply chain relationships at the primary level to address possible concerns before they can emerge. Wuttke, Donohue, and Siemsen (2018) propose suggestions for the integration of the discipline’s findings into supply chain contracts such as the replacement of penalties with rewards, adjust the demand for innovation value, and consistency. All of these measures would make the supplier more likely to accept the contract because they would perceive it as less risky and more rewarding. Innovation is particularly important, as companies that invent disruptive products may be concerned that their technology will be analyzed and appropriated by industry leaders. Maier, Korbel, and Brem (2015) propose the use of the latest technologies to try to resolve this agency dilemma by reducing information asymmetry before the contract’s inception. By selecting the appropriate agent and incentivizing them to promote the success of the entire network, a company may mitigate risks.

Transparency is essential to the elimination of information asymmetry, and the behavioral supply chain discipline has created a solution to the problem. Kharlamov and Parry (2018) discuss the use of blockchains to improve visibility without overwhelming people with excessive amounts of data. The technology can streamline supply chains to a large extent and introduce massive efficiency improvements, but people may show many biases against it. As such, debiasing approaches are essential to foster acceptance of the framework among consumers and suppliers. Apte and Petrovsky (2016) highlight the strength of the method with regards to excipient products, which have to be delivered quickly and safely before they expire. Automated and optimized technologies can contribute to this goal considerably if people learn to trust them.

Transformational and Transactional Leadership

A supply chain manager is a leader for his or her subordinates and should strive to perform as effectively as possible in the role. The contemporary Western leadership theory focuses on two specific styles, transactional and transformational, and there is some evidence that either one can be applied to supply chain management (Gosling et al. 2015). However, many works concentrate on one style or another without comparing them directly, which determines whether one approach or the other is the more effective challenge. The most likely cause is that both styles are situationally appropriate, but then it is necessary to understand the specific situations when either should be used. This section will discuss current literature on the topic of leadership and supply chain management.

Appropriate leadership is central to changing the particulars of the performance of a supply chain, as such initiatives require strong direction. Gosling et al. (2015) discuss how multinational corporations use transactional and transformational leadership or some combination of the two to create sustainable supply chains. They change the approach based on the situation, and so knowledge of both is crucial to a manager to be able to respond to changes in the environment. The finding is supported by practical examples from other literature that shows the positive influence of both styles on various aspects of supply chain management. Ul-Hameed et al. (2019) associate the two with improved supply chain performance for companies based in the United Kingdom. Many other examples exist that show that both approaches result in benefits for the company and its network of partners.

With two possible approaches existing, the question of when one or the other is more appropriate arises naturally. Jacobs and Mafini (2019) discuss the benefits of the transactional style in fast-moving industries for improving supply chain quality and, therefore, business performance. However, the study does not test the transformational style in the same circumstances, a failing that can be attributed to much of the literature on the topic. Few studies concentrate on the relative influence of both styles in the same situation, possibly due to the difficulty of conducting an experiment and comparing data in real economic circumstances. Chan et al. (2019) claim that transformational leadership can have a positive effect on supply chain innovation, but do not mention the transactional style. As such, future research needs to cover the gap in the literature and discuss the correct blend of management styles for optimal effects.

Nevertheless, there is strong support in the literature for the use of one or both of the styles discussed in this dissertation. Mzembe et al. (2016) discuss the benefits of the transformational style as one of the primary drivers of corporate social responsibility in the tea industry. The finding has been known for some time, as such initiatives typically require top management involvement to succeed. However, firms that attempt to implement socially responsible practices may encounter unexpected difficulties, mainly if they do so to achieve positive publicity. Blome, Foerstl, and Schlepper (2017) claim that the two styles conflict with regards to reducing greenwashing and implementing green practices, but neither is sufficient to achieve the goal alone. As such, further research is necessary to address and resolve the concerns.

Risk Management

Risk management is a discipline that pervades every aspect of entrepreneurship. As such, it should be possible to apply its tenets to supply chain management to minimize the danger that a company has to consider. As implied by the name of behavioral supply chain management, the behavior of other supply chain members is the primary concern in it. It is possible to take measures such as increased information sharing that affect their decisions and actions in a manner that benefits the company (Hoque, Sinkovics, and Sincovics 2016). This section will discuss methods for reducing risks, both for the company and its suppliers, to increase the willingness of both to engage in partnerships.

Companies should provide sufficient rewards to their suppliers to mitigate the issues that tend to appear with contract acceptance and the associated risks. Zhang and Li (2014) propose an integrated project delivery model for construction projects, in which all participants share the risks and the rewards. It may be expanded into other industries, as well, though it will likely have to shift away from the project-focused nature of the construction sector. Managers should also reconsider their approaches to control, as it tends to affect risks and general productivity. Liu et al. (2017) discuss the factors that contribute to private control as opposed to collective control such as goal incongruence and power asymmetry and advise managers on measures to alleviate them. By selecting a compatible partner, suppliers will find it easier to engage in closer relationships and reduce risks.

Existing partnerships can also benefit from the removal of inequality, particularly about knowledge. Hoque, Sinkovics, and Sincovics (2016) claim that suppliers typically lack access to the tacit knowledge of their buyers, a fact that limits their ability to upgrade their offerings and introduces risks into the relationship. An established knowledge transfer procedure would enable the supply chain members to request pertinent information and receive it, while the informal system that existed resulted in them relying solely on information from repeated purchases. As such, it is best if companies establish and promote a knowledge-sharing mechanism within their supply chain. Liu, Shang, and Lai (2015) propose an incentive mechanism that can achieve considerable success but notes that it is incomplete as it does not take end customers into account. As such, further research is required to complete the model and ensure that it is applicable in every situation.

Lastly, the supply chain manager should take the existence of dishonesty and fraud into account and be ready to recognize and stop such practices if the necessity arises. Patterson, Goodwin, and McGarry (2018) claim that due to a lack of fraud research outside of accounting, the activity can be challenging to identify and propose a comprehensive auditing plan and identification problem as a partial solution. Global supply chains are particularly subject to fraud due to the difficulty in controlling each member across vast distances. The practice is particularly important in environments where the product is critical, and failures are life-threatening, such as the food industry. Esteki, Regueiro, and Simal-Gándara (2019) discuss the prevalence of fraud in the sector and propose a variety of methods that try to address the issue. Failures to identify and prevent supply chain fraud can lead to the collapse of the company as a whole, making them a vital topic.

Culture Adjustment

As discussed above, organizational culture can be a significant determinant in the success of supply chain relationships, and managers should work to adjust it in a manner that maximizes benefits. However, first, they have to understand the specific traits they should strive towards as well as the best methods to achieve them. It should be noted that these optimal characteristics may vary between companies and industries, and so the manager should be competent at analyzing the situation (Dike and Kapogiannis 2014). As such, this section will discuss examples of desirable organizational cultures and methods one may use to determine and implement them based on the situation.

An organization should have the appropriate internal culture before it can begin directing adjustments among its supply chain partners to provide them with an example and a guarantee of honesty and goodwill. Makhdoom et al. (2016) claim that while supply chain integration improves performance, it is moderated by the company’s organizational culture. A particular approach, which the authors define as a “group culture”, was preferable to the rest in terms of outcomes, though the finding contradicts some prior research. Furthermore, sometimes the attitudes of the broader industry require addressing before the performance of the participants can be improved. Dike and Kapogiannis (2014) note that the British construction industry is highly adversarial, a trait that prevents members from collaborating or integrating. As such, its general culture would have to change to a more cooperative one before companies could improve their supply chain performance.

A particular set of qualities may be particularly beneficial to supply chain performance and should be fostered wherever it is appropriate. Pantouvakis and Bouranta (2017) promote the idea that there is no universal culture for a company organization and that each should be organized in a manner that changes with its needs, with port industries adopting learning cultures to improve their agility. Sectors that are less in need of quality may choose to select a different set of values to suit their needs and those of the consumers. Nevertheless, the adoption of a specific set of guidelines requires considerable amounts of work, such as the formulation of rules and values and the education of employees. Agus and Ismail (2016) discuss the importance of personnel training in supply chain management and its impact on differentiation and performance. In doing so, companies will improve the performance of their workers while preparing for an increased supply chain orientation.

Socially responsible practices have to be incorporated into the organizational culture to be successful, as well. Michalski, Botella, and Figiel (2018) state that a corporate social responsibility framework should be integrated into the core of a company’s activities, including its supply chain. As such, its values should be known and understood by every employee for optimal operation in current and future enterprises. Similarly, sustainability should be tightly integrated into supply chain management as an essential component, as relationship longevity is vital to successful integration. Rezaee (2018) proposes a model that can be integrated into organizational culture and spread into general business practices and supply chain management. The approach protects the interests of all stakeholders while creating value and optimizing operations, leading to global benefits.

Trust Creation

It can be challenging to create trust in supply chain relationships, especially if there are no contracts yet and one of the parties is trying to convince the other to agree to become a supplier. Dabhilkar, Bengtsson, and Lakemond (2016) claim that there is a specific commitment configuration that ensures a stable long-term relationship, and deviations from it lead to harm. Furthermore, the methods for achieving the goal may be unclear due to a lack of specific information on the topics. As such, this section is devoted to the analysis of contemporary behavioral supply chain management research on the creation of trust and commitment among suppliers.

Trust is essential to successful collaboration, as companies would be reluctant to commit to a close relationship with a company whose intentions were in question. Soosay and Hyland (2015) identify a variety of collaboration types, associate them all with trust, and propose a variety of different modes of sharing. Knowledge sharing has been discussed above, and partners may be more willing to trust a company that is forthcoming with its information and technology. However, there are also other forms of resource sharing that help integrate the supply chain in a closer manner and create trust between the partners. Gong et al. (2018) discuss the practices of revenue and profit sharing that are present in online enterprises and conclude that the latter is more beneficial for suppliers. As such, companies that sell products via the Internet should consider the notion when planning their supply chain management.

Distrust is often caused by the inability of a company to know the partner’s situation and intentions, as people are generally moved to assume the worst outcome. According to Salam (2015), information technology can mitigate the issue by fostering cooperation alongside trust and building the latter as the relationship progresses successfully. Integration via a technological platform enables the partners to view a considerable amount of information about each other and makes data falsification considerably more difficult. The approach also has a variety of other benefits that contribute to the improvement of a company’s general supply chain management capabilities and performance. Jadhav (2015) describes the benefits of using a comprehensive IT strategy as vast, encompassing a higher organization quality, improved information exchange, mistake prevention, and other aspects. As such, companies should look into establishing and expanding their use of information technologies to improve their supply chain performance.

Trust becomes particularly challenging to achieve in environments that manifest a power asymmetry, enabling one side to exploit the other to obtain an advantage. According to Dabhilkar, Bengtsson, and Lakemond (2016), the ideal collaborative supply chain relationship is characterized by high interdependence, which creates high exit barriers for both parties and promotes a productive, long-term relationship. However, such an environment will be challenging to achieve in an asymmetric situation, as the more dominant side can likely quickly leave the agreement while the weaker one cannot. As such, action is necessary to reduce asymmetry or its adverse effects on the parties, with the second goal usually being more comfortable to achieve. Hingley, Lindgreen, and Grant (2015) propose the use of logistics services as intermediaries as an effective measure to improve relationships between buyers and consumers. The approach involves a horizontal system, which has not received as much attention as its dyadic and vertical counterparts, and so further investigation is required to determine its viability and effects.

Analysis

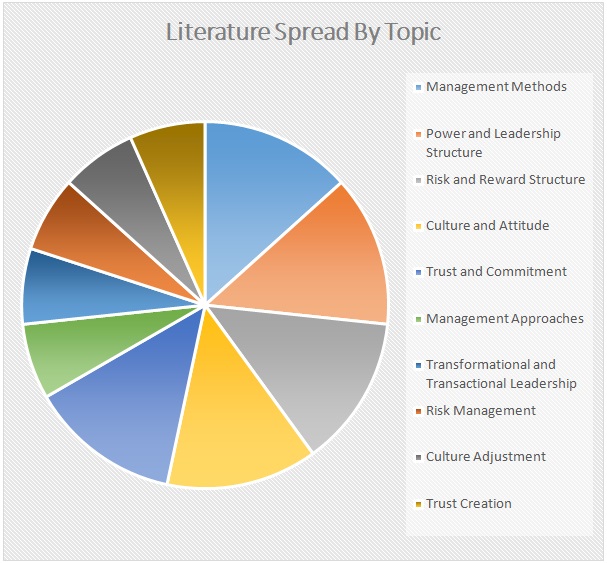

Overall, the search yielded a considerable amount of literature on every topic, as can be seen in Figure 1. Personal attitudes and behaviours can exhibit considerable influence on the relationship between a company and the members of its supply chain. They may respond poorly to attempts to manage their operations in a specific manner, especially when there is a power imbalance. They may refuse to cooperate outright if they view the risks of the partnership as more significant than the reward. Even when the relationship is secure, attempts to improve it may encounter difficulties due to misaligned organisational cultures and priorities or a lack of trust on the part of the partners. These issues are beyond the scope of traditional supply chain management, which presents companies as impartial mechanical actors. As such, it is not capable of addressing them in their entirety, and an approach that considers human behaviour becomes necessary.

Supply chain managers should possess a set of fundamental competencies that enables them to direct teams and negotiate with people. Their role is to ensure that the relationships with its partner companies are friendly and cooperative and that the supply chain department of their company operates smoothly. As such, interpersonal competencies are critical for the position, both to motivate subordinates and to negotiate with partners as equals. As can be see in Table 1, the suggested response is to develop a robust set of managerial skills. Emotional intelligence is highlighted as a particularly important aspect of the necessary skills, as it enables the manager to understand others’ mental processes better. Lastly, technical competencies are critical for the manager to be able to incorporate the latest innovations in supply chain management and improve the operation of the company. They will likely not be introducing any technological advancements personally, but an understanding is necessary to estimate the scope of the project and the time required to complete it.

Many supply chain environments are characterised by a power imbalance, which is often inherent and cannot be eliminated by the efforts of a single organisation. Such situations frequently occur when buyer or supplier power is excessively high in the industry through an abundance of options on one side and the presence of a small group of dominant organisations on the other. The latter can then force unfavourable conditions on the former, which have no choice other than to agree, to maximise profits. In different situations, a group of supply chain members can unite against another member to obtain better conditions for themselves at its expense. While they generally benefit from the arrangement in the short term, it is ultimately not healthy for the market. Instead, the environment evolves to a degree where no one benefits, and often, external intervention is necessary to address the issues that caused the situation.

Companies that abuse the market’s power structure to profit at the expense of their partners tend not to be competitive, preferring the status quo. As such, if buyers receive lower prices from suppliers, they will generally not transfer these cost reductions to the consumer. Then, the industry may stagnate as a result and become similar to an oligopoly, with the weaker side being driven out of business through low profits. They can also adopt cost-saving measures that create pollution and result in social irresponsibility out of necessity. Lastly, companies that are exploited by their partners are unlikely to be interested in entering a closer partnership due to a variety of concerns. It is possible to force them to do so regardless, but overall, the situation should be avoided if possible.

Companies may refuse to engage in partnerships if they see them as overly risky. Many different issues may arise in supply chain relationships, such as disruptions and mismatched order sizes. Uneven circumstances present the concerns that the partner may demand unacceptable conditions in the future and force them on the company. All of these issues intensify when companies in a relationship decide to integrate closer. The process usually involves knowledge sharing, and concerns exist that the buyer will appropriate the supplier’s technology or vice versa and use it to develop competing products, then abandon the relationship and become a competitor. As such, companies need a valid reason for cooperating that outweighs their worry over the potential danger. Alternatively, they can be convinced to do so if they trust the partner, but any such feelings are unlikely to exist between companies entering a partnership for the first time.

The promise of a high reward is a direct answer to the fears, as it compensates for the potential damage from risks that turned into failures. Table 2 recommends the use of benefit-based contracts instead of the traditional penalty-oriented ones. The incentive does not necessarily have to be monetary, but it has to have value to the other party. Innovation is a prominent example, as access to knowledge and technology can allow suppliers to develop offerings that are superior to their prior versions. As the value of the risk is difficult to estimate, the perception of the balance between risk and reward is vital in influencing the other party’s decision. As such, the manager should understand the factors that affect people’s perceptions and motivate them to accept offers and use them to secure partnerships with supply chain members.

Many companies, particularly large multinational corporations, are seen as responsible for the behaviour of their suppliers nowadays, a finding reflected in Table 3. As such, their efforts to incorporate corporate social responsibility practices such as better working conditions or green improvements have to extend up through the supply chain. Doing so is highly challenging if the company and its suppliers are not aligned in their culture and objectives, as direct control may be highly problematic. The company’s partners may be located overseas and adhere to different regulations or report the results of their efforts differently. As such, they may present information that satisfies the company but creates a public outcry when the media uncovers the real conditions. As such, similar attitudes to improvement and reporting are essential to success in the deployment of CSR initiatives.

Lastly, trust is critical to the success of a supply chain relationship, particularly concerning integration. When companies trust each other, they can share information and knowledge to improve their cooperation. They are not concerned about the danger of the other party exploiting that information for gain at the expense of the provider, an issue that surfaced during the review and is described in Table 5. However, it should be noted that the threat does not disappear, and when trust between companies is disproportional, one may abuse the imbalance. As such, companies should be more concerned about increasing their partners’ confidence than their own and let the actions of the supply chain members inform the manager’s opinion of their reliability.

A supply chain manager should try to foster a trusting and committed relationship because of the multitude of benefits that accompany it. There is potential for improvement in all aspects of the process, which are usually complicated by the distance between the different members. In particular, the companies can save time with efficient logistics and the redirection of waste into recycling and further production. The changes can simultaneously improve the chain’s adherence to environmentally friendly practices and reduce costs while improving productivity. As such, a successful relationship will result in significant improvements at little to no cost to the supply chain members. A manager should work to achieve this goal, and an understanding of behavioural factors is critical for such an effort.

The behavioural branch of supply chain management has emerged in response to these concerns, but it currently still relatively new and insufficiently explored. With that said, researchers have achieved significant results already, and the findings should be of interest to every supply chain manager. Many of the propositions should be integrated at the basic level, such as the incorporation of the promises of benefits and incentives into contracts instead of risks and penalties for failure. Behavioural supply chain management also makes excellent use of the latest advances in technology, promoting the blockchain as an innovative approach to the discipline that addresses many of its issues. Technology is also prominently featured in its promotion of transparency, enabling partners to see accurate information about the company and improving their trust in its honesty and integrity as a result.

To implement an initiative, the company has to lead its partners in the effort. The supply chain manager is the central person in such a situation, as he or she interacts with the other supply chain member directly. Research shows that the transactional and transformational leadership styles are appropriate for the task, though both have some disadvantages. As such, companies that succeed at implementing changes employ both methods when and where necessary or combine the two in specific situations. However, the literature on the situational uses of various leadership styles still lacks depth, as it mostly focuses on the exclusive use of one or the other. Managers will have to rely on experience and other competencies in determining how to approach a given situation until the situation changes in the future.

In addition to emphasising rewards when moving companies to enter partnerships and commit to integration, supply chain managers should conduct comprehensive risk management. Knowledge sharing among members can help mitigate the bullwhip effect through the generation of accurate forecasts. It can also help analysts predict potential weaknesses or failures in the system and address them before a critical issue surfaces and damages the company’s operations. Lastly, managers should be aware of intentional supply chain fraud, which is currently prominent in many locations due to the lack of attention to it from companies and researchers. Estimates show that a significant portion of the overall supply chain turnover worldwide is fraudulent, indicating a long history of neglect. However, contemporary research suggests a multitude of methods companies can use to ensure that their suppliers are honest and have the relationship’s best interests in mind.

When trying to shift a supply chain’s organisational culture, a manager should understand the specific characteristics that he or she should aim to achieve. The situation is complicated by the prevalence of specific harmful attitudes in the industry as a whole as well as by the different needs of particular sectors that emphasise specific aspects, as can be seen in Table 4. A manager should learn the needs of their company and the traits that suit it best, then work to incorporate them into the workings of the enterprise. Worker training is highlighted in the literature as an essential part of any such change, as they may remain unaware of the change, ignore it, or resist the effort otherwise. Research also discusses the importance of alignment in corporate social responsibility initiatives with regards to implementation as well as reporting.

Lastly, trust creation is a separate category due to its importance to the overall operation of the supply chain relationship. The literature suggests that a company should be forthcoming with its trust and resources to create a trusting relationship, though a degree of caution is still necessary. Resource sharing, in particular, is an effective method of ensuring the continued cooperation of the supply chain members. Information technology may also be a driver of trust by enabling partners to view each other’s information without worrying over the accuracy of its presentation. The optimal configuration is one where both partners receive considerable benefits and have high exit barriers that prevent them from ending the relationship. However, in industries where such a situation is not possible due to a power imbalance, the use of intermediaries may help mitigate the issue and create trusting relationships regardless.

Conclusion

Behavioural supply chain management is still a relatively young discipline, and many of its areas remain unexplored. However, it has achieved considerable success, and every supply chain manager should look into it. Researchers have been able to describe the primary concerns that currently present themselves in everyday operations and describe their influences as well as the impacts of their elimination on the company’s performance. They have found that human attitudes and behaviours are highly influential and can enhance supply chain performance with little to no cost when taken into account or result in devastating failures when ignored. The literature has also been able to identify a multitude of avenues for improvement as well as specific methods that can be used by managers to improve performance. However, this literature review has discovered several weaknesses in the theory and practical suggestions that should be investigated by future researchers.

Appendix A

Appendix B

Table 1: Management Methods Issues and Answers.

Appendix C

Table 2: Power and Leadership Issues and Answers.

Appendix D

Table 3: Risk and Reward Issues and Answers.

Appendix E

Table 4: Culture and Attitude Issues and Answers.

Appendix F

Table 5: Trust and Commitment Issues and Answers.

Bibiliography

AFOLAYAN, A., WHITE, G.R. and MASON-JONES, R., 2016. Why knowledge acquisition is important to effective supply chain management: the role of supply chain managers as knowledge acquisitors. 30th Annual Conference of the British Academy of Management. 2016. Web.

AGUS, A. and ISMAIL, R., 2016. The importance of training in supply chain management on personnel differentiation and business performance. World Journal of Management, 7(1), pp. 44-61.

AKAFIA, E.K., MUNTAKA, A.S. and BOAHEN, S., 2017. Impact of service operation strategies on the supply chain performance of private automobile companies in Ghana. Journal of Logistics Management, 6(1), pp. 11-25.

AMBILIKUMAR, C.K., BHASI, M. and MADHU, G., 2016. Effect of information sharing on the performance of a four stage serial supply chain under back order and lost sale situations. International Journal of Supply Chain and Inventory Management, 1(2), pp. 91-117.

ANIN, E.K., ESSUMAN, D. and SARPONG, K.O., 2016. The influence of governance mechanism on supply chain performance in developing economies: insights from Ghana. International Journal of Business and Management, 11(4), pp. 252-264.

APTE, S. and PETROVSKY, N., 2016. Will blockchain technology revolutionize excipient supply chain management? Journal of Excipients and Food Chemicals, 7(3), pp. 76-78.

AVOTA, S., MCFADZEAN, E. and PEISENIECE, L., 2015. Linking personal and organisational values and behaviour to corporate sustainability: a conceptual model. Journal of Business Management, 10, pp. 124-138.

AZIZ, F., MAHADI, N. and BASKARAN, S., 2017. Fostering employee pro-environmental behaviour: does emotional intelligence matters? International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 7(10), pp. 567-575.

BHATIA, S., 2018. Creating a culture of honesty and integrity in supply chains. Asian Journal of Management Sciences & Education, 7(1), pp. 55-61.

BIRASNAV, M., MITTAL, R. and LOUGHLIN, S., 2015. Linking leadership behaviors and information exchange to improve supply chain performance: a conceptual model. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 16(2), pp. 205-217.

BLOME, C., FOERSTL, K. and SCHLEPER, M.C., 2017. Antecedents of green supplier championing and greenwashing: an empirical study on leadership and ethical incentives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 152(C), pp. 339-350.

BÖLÜK, G. and KARAMAN, S., 2017. Market power and price asymmetry in farm-retail transmission in the Turkish meat market. New Medit, 16(4), pp. 2-11.

BON, A. T., ZAID, A. A. and JAARON, A., 2018. Green human resource management, green supply chain management practices and sustainable performance. The 8th International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management. 6-8 March 2018. Bandung: Institut Teknologi Bandung. pp. 167-176.