Introduction

The challenge of managing knowledge in an organizational context lies in effectively harnessing multiple knowledge sources into coherent business intelligence and embedding the intelligence into the organization’s memory. As the notion of Knowledge Management (KM) matures, it is increasingly clear that KM is not just about technology, and cannot be realized simply through information systems. Knowledge and management of it emphasize and expect a collaboration between a wide spectrum of contributors that ranges from people and processes to supportive technologies in an organization.

Historically there has been a perceived disconnection between technologists and business managers as it relates to Information Technology (IT) solutions in business contexts. Technologists typically view IT from the perspective of capabilities, where the focus is on specific functionalities and interfaces afforded by the solution to the users. Business managers tend to evaluate IT solutions from a strategic or business process enablement perspective [12].

In this paper, we suggest frontiers for KM efforts in the business domain. As has been recognized in a variety of disciplines, knowledge in the business context is a somewhat nebulous resource. To build a foundation for KM, efforts need to be directed for addressing issues related to knowledge storage and retrieval, knowledge sharing and knowledge synthesis. Using arguments grounded in existing theory and literature, we identify coordination mechanism for business processes as the knowledge context. This paper takes these issues into account and adds to the discussion by reporting the findings from a field study on the establishment of KM in a Danish high technology company. Our focus is on the process of establishing KM as opposed to the process of conducting KM, on the actions of the employees at the organizational level of the company (referred to as organizational members or members), and on how these actions are influenced by, and influence, the members’ meaning construction and perceptions as the process unfolds. Based on a grounded theory approach to the analysis of empirical data, a model of establishing KM in organizations is developed and used to suggest an explanation of why setting up KM was not successful in the case which was investigated.

Knowledge storage and retrieval provide a unique challenge to researchers as data management systems as a general rule use indices to store data and effectively the same indices are used to retrieve the data. As such orientations to storage and retrieval are closely tied together. For KM systems, storage approaches and retrieval mechanism are not necessarily congruent. Single level storage and retrieval mechanism cannot be applied in KM, necessitating an ontological orientation. The utility of this orientation is illustrated via a failure analysis/failure identification KM system developed in the context of a semiconductor manufacturing organization.

Knowledge sharing addresses the needs related to generation and collaborative aspects of knowledge. Knowledge artefacts–data and information–used in the sharing and generative processes are inherently unstructured. Furthermore, these artefacts come from disparate sources causing the sharing process to be asymmetrical in orientation. We instantiate the complexity associated with knowledge sharing by presenting a real-time knowledge sharing case in the context of bioterrorism surveillance. Success in this setting is inherently predicated on effective and efficient knowledge sharing among sentinel data gathering sites, first responders and epidemiologists. The case illustrates the challenges that emerge from information asymmetries, unstructured data transfer and the opportunistic problem solving necessitated by discontinuous data, information and knowledge sharing.

Before delving into our approach to creating a context for managing knowledge, it is instructed to briefly review the extant literature on KM. While the conceptual foundations of KM were laid out in the work of several management researchers in the early 1960s [18], [35] and [46], a more formal treatise of the concepts related to Knowledge began to emerge in the 1980s, especially as the resource-based view of the firm began to gain currency [59]. The dominant theme in the KM literature in the 1990s reflected the increased emphasis on downsizing and responsiveness to customers and therefore focused on reengineering and process-based view of the firm [27]. More recent literature in this area has explored some knowledge and KM related issues [1], [3], [9] and [16]. Themes in recent literature have explored mechanism design for optimal investments in knowledge [5], knowledge characteristics and organizational structure [8], knowledge creation and process change [13], knowledge reuse [36] and knowledge transformation [11]. A summary of the evolution of KM as a research area is provided in Table 1. Some of the cited sources in the table provide a more detailed overview of issues related to organizational knowledge and KM.

Literature Review

KM literature draws heavily from a related stream of research that has attempted to characterize and classify knowledge itself. This stream of research helps establish the rationale for varied approaches to managing knowledge due to the inherent complexities of knowledge artefacts. Polanyi [47] initiated the discussion of knowledge classification and introduced the notion of tacit and explicit knowledge types. By definition, tacit knowledge is acquired through experience and explicit knowledge can be acquired through articulation and codification [54]. Technology applications aimed at facilitating KM have been more successful in dealing with explicit knowledge. Attempts at facilitating tacit knowledge transfer and acquisition have focused on communication and networking technologies [6]. Research over the past few decades has identified Knowledge storage and retrieval, knowledge sharing (or transfer) and knowledge synthesis (or creations) as the three main facets of KM processes in organizations [11]. In the rest of the paper, we discuss the emerging facets of KM using these three facets as the main drivers of KM efforts in organizations. Our discussion argues for a clear application context for KM efforts and uses the coordination mechanism in business processes as this context.

Knowledge context

It is generally accepted that performance improvements from KM and associated technologies result when knowledge is applied [1]. The application of knowledge is to a large extent driven by its context which defines the intent of usage. KM efforts have been developed and studied in a variety of contexts as detailed in the previous section. For purposes of this paper, we restrict our focus to a business decision and process setting as we describe a knowledge context. Business knowledge is defined in the extant literature as a complex conglomeration of information, workflow, decision and collaborations and all the associated interactions. The inherent complexities and challenges for managing knowledge in a business context have been well documented. The KM literature in the business context, hence reported numerous successes through the extensibility of these successes to a wider context has revealed persistent problems [15]. Problems with KM and knowledge sharing are well documented and often result from a lack of applicability of available knowledge. Often, technological solutions aimed at providing employees with a means to exchange, publish and use knowledge related to their expertise fail for reasons completely unrelated to technology issues [23]. We argue that these problems arise when investments in KM processes and KM technologies are made without a specific knowledge context [58]. For this paper, we define a knowledge context with an operational focus, where the knowledge unit and the KM efforts are intertwined and indistinguishable. Critical to this orientation is a definition of an operational context for knowledge and its application provided by the business process.

Business process as knowledge context

Business processes are a collection of interdependent activities or tasks organized to achieve specific business goals. Business processes often cut across multiple functional organizations and hierarchies within and outside the organization and therefore require that the activities within the process be coordinated to achieve the business goals effectively. Researchers have attempted to gain a better understanding of business processes through the concepts of coordination framework [37], [38] and [51]. Coordination is defined as arranging or organizing to achieve a desired or effective combination [55]. Coordination is achieved through mechanisms that are created to bind or organize the various aspects of a business process to meet the process objectives [50].

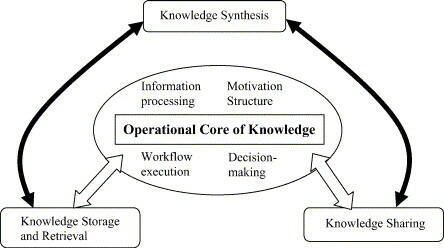

Extending the coordination framework developed by Raghu et al. [50], four key aspects form the knowledge context kernel as shown in Fig. 1: workflow execution, information processing, decision making and motivation structure. We assert that all four of these components interact with each other and with KM processes in complex ways to result in an operational core of knowledge that should be addressed in any KM effort.

Workflow execution

Activities and precedence relationships among the activities together form the workflow structure of a business process [29] and [56]. Workflow concerns usually revolve around issues of efficiency and flexibility. To increase the workflow efficiency of a process, organizations typically focus on reducing handoffs, increasing concurrency or increasing automated tasks within the process [28]. On the other hand, organizations seeking to increase workflow flexibility focus on increasing the number of cross-trained workers and improved resource allocation mechanisms [10] and [34]. In either case, organizations face coordination and management problems when attempting solutions to efficiency and flexibility problems. For example, concurrency in workflow causes coordination problems that need to be solved through improved communication and information flow structures. Allocation of cross-trained workers requires careful consideration of the knowledge capabilities of the individual workers for optimal allocation.

The utility of workflow in a KM context arises from several perspectives. Production oriented workflow processes such as customer support, claims to process, call-centre activities benefit from easy retrieval of past workflow instances of similar contexts. KM efforts directed at improving access and retrieval for such information can therefore improve workflow efficiency and consistency. Definition and dissemination of business rules that define the protocols of workflow instance execution improve the effectiveness of the workflow and perhaps, its efficiency. The definition of business rules requires effective knowledge capture from both within the organization as well as best practices from the industry.

Given the dynamic and competitive nature of today’s business, the capabilities of workflow structure within business processes take on added importance. Adaptation and knowledge synthesis within a workflow context occurs through a complex interaction between KM processes and workflow structure. For example, to be able to learn from the past incidents in a technical support context, personnel should be motivated to document and detail the problem-solving process in each incidence. Better documentation can potentially yield additional rules of interaction or opportunities for increasing concurrency within the workflow. However, documentation of the problem-solving process interferes with workflow efficiency goals. Interestingly while the complementary nature of KM and workflow is undeniable, the contradictory goals of KM effectiveness and workflow efficiency present some interesting challenges to KM efforts.

Issues related to efficiency and flexibility contributes to the operational core of knowledge in the workflow execution context. Workflow optimization efforts focus on achieving excellence in the execution of routine tasks and thereby achieve efficiencies. Inherent in routine activities is the repeated interaction of employees over time with the business environment. Therefore, knowledge synthesis in a workflow context arises from the systematic discovery of repeating patterns and creating an optimal set of activities to optimally address those patterns. Flexibility in the workflow is achieved through a cross-trained workforce. [62, 63] However, differential levels of skills among employees can conflict with the goals of achieving efficiencies. Fortunately, Knowledge synthesis efforts that improve workflow efficiency can also enable flexibility through shared knowledge of patterns in workflow execution. When augmented with other means of systematic training and hiring policies, greater flexibility in workflow execution can be achieved.

KM strategies and efforts in workflow execution contexts often begin with the codification of explicit knowledge. Knowledge capture often occurs through structured database-oriented solutions that capture the explicit aspects of the problem-solving process. Capturing the business rules and integration of the business rules within workflow execution engines provide the learning and adaptation context. The direct association of KM with workflow can result in higher-order learning and adaptation through improved process monitoring and benchmarking practices.

Information processing

The Information Processing (IP) paradigm from information theory [57] views organizations as being composed of units whose main function is to process information by exchanging messages among themselves [51]. A key objective of information processing activities is to respond to environmental uncertainty by processing and exchanging information. Additionally, the information processing paradigm [52] and [53] also takes into account the bounded rationality and bounded recall characteristics of humans. Since members of an organization are constrained by these cognitive limits to behaviour, their goal is to conduct heuristic searches for satisfying decisions which meet a psychologically determined level of aspiration.

Often business problems are based in a specific environment about which there is a lack of complete information. Therefore, specific interactions with the environment have to be defined to explore and acquire additional information. Each of the information-gathering activities, however, has a cost associated with it. Additionally, in these problem-solving situations where there is a computational cost, such cost needs also to be taken into account. The objectives of KM and IP run parallel in process design contexts, i.e., maximize the payoff by the right choice of action without excessive informational and computational costs [41].

Information processing functions in business processes are designed to minimize the computation, acquisition, and communication costs (all the three put together would be termed as the coordination costs of information processing). The design space includes information coordination, i.e., getting the right information to the right person at the right time to produce the right processed information, for example, in the processing of product design-related information, budget planning, etc.

In drawing parallels between IP and KM, information coordination is of utmost importance in processes that execute periodically, e.g., project planning, budgeting, strategic planning, product design, etc. Such processes often lack the rich patterns of learning that could be obtained in a workflow context. As such, knowledge storage and retrieval in information coordination contexts focus on storing documents, reports and computational aids (e.g., spreadsheet models) to reduce the cognitive burden on knowledge workers. The nature of stored artefacts facilitates knowledge reuse rather than knowledge synthesis. Knowledge synthesis in information processing contexts could be facilitated through knowledge sharing and business intelligence systems [2] and [19]. Computer-Supported Collaborative Work (CSCW) systems and group systems are thus aimed at improving knowledge sharing through improved collaboration.

At the outset, process goals and KM goals seem to be less contradictory in information processing contexts when compared to workflow execution. Business intelligence systems entirely built on top of transactional and enterprise-oriented systems, and as well as external information sources are less susceptible to failure due to conflicts emerging from behavioural attitudes. This enables informational coordination through KM efforts to be less problematic. However, enabling and enhancing collaboration through KM systems is a much more challenging task. Lack of motivation among individuals and groups to participate in knowledge and information sharing activities has often been cited as among the primary causes for the failure of CSCW and collaborative systems [17] and [21]. This can be attributed to the fact that in some cases there is a disincentive to participate in sharing activities altogether.

The existence of enterprise systems and databases results in less of a need to invest directly in the codification of knowledge for storage and retrieval purpose. However, it becomes essential to create at least a rudimentary taxonomical knowledge structure when knowledge and data from a variety of sources have to be integrated and reconciled. Facilitating collaboration can benefit a great deal from both codification of knowledge and additional process-related workflows to ensure that shared knowledge persists in organizational memory.

Decision making

The impetus for creating explicit decision-making structures in business processes emanates primarily because it is not possible to centralize all the relevant information for decision making, expertise and control within a business process. The reasons for the distribution of decision-making rights in a business process are due to bounded computational resources, and the limitations of time. The distributed decision-making structure in effect creates a form of organizational memory [60].

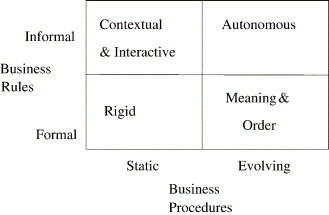

Decision-making components in a business process that aid in the achievement of process objectives and solutions include business procedures and business rules. Procedures govern the sequence of actions or heuristics that interpret and implement business rules. It is these procedures and rules that are intended to govern the actions of the members (or agents) in the day to day execution of the business process. [61] While workflow patterns can often embody business procedures, individual tasks also constitute enactment of business procedures, thus meriting separate consideration under the decision-making structure. As will be discussed later, controls and motivational aspects of the coordination mechanism are necessary to ensure that actions conform to the business rules and procedures. The decision-making structure and associated KM implications can be analyzed based on a dichotomous classification of business rules and procedures as shown in Fig. 2. See appendix.

In Fig. 2, a decision-making structure that has formally defined business rules and where decision procedures follow the rules without room for alternative interpretations is termed rigid. Most bureaucratic processes can be characterized as being static and formal. For instance, the process of filling a prescription for a patient is a formal process, where the prescription has to be written by a practising physician and has to fulfil pre-specified requirements, failing which the pharmacist will not fill the prescription. A decision-making structure that is evolving in procedure and formal in the application of rules is considered as being oriented towards meaning and order. An example from the business domain includes Personnel policies, such as granting vacation time. While the formal rules are intended to ensure equity in the process, the procedures that implement the rules tend to evolve to allow some amount of flexibility in the interpretation of the rules.

A decision-making structure comprising of static procedures, but informal rules are considered contextual and interactive. Tender processing is one example of such a process. The tender process follows a highly formal decisional procedure. However, the rules used for the decision choice are somewhat informal to accommodate better tenders, which may however not meet certain preset requirements. A decision-making structure that is evolving in procedure and informal in business rules is considered autonomous. This is the most flexible among the possible decision-making structure designs. Ideally, business rules and procedures for sales, marketing, purchase, and customer relations should fall under this category. Different business processes of an organization employ different decision-making structures to suit the needs of the objectives of the process being performed.

Rigid decision-making structures tend to benefit the least from KM efforts. Any innovation or knowledge synthesis in the decision-making structure will have to be externally influenced through a change initiative. Decision-making structures emphasizing “meaning and order” would benefit from KM efforts that drive innovations geared towards increasing the efficiency of procedural aspects of decision making. As with rigid decision-making structures, innovations and synthesis in business rules can only come through external influence. In essence, processes that emphasize formal business rules tend to depend on external forces for driving knowledge innovations in the process. We assert that technological solutions would have a limited impact in such scenarios.

Contextual and interactive decision-making structures depend on the effective interpretation of informal business rules. KM efforts designed to better store and retrieve lessons learnt from past decision-making episodes would be beneficial in this regard. However, due to a static procedural orientation, knowledge within the context of the decision-making problem would be useful. There is very limited scope for learning from decisions made in contexts outside of the problem domain at hand. On the other hand, autonomous decision-making structures are the most amenable to knowledge sharing and storage and retrieval solutions. Such decision-making structures benefit from interactivity among decision-makers both within and outside the process domain; they also benefit from retrieving knowledge related to solutions and procedures applied to similar decision problems from within and outside the problem domain.

Motivation structure

A stream of research dealing with Agency relationships [30] recognizes that the decision-makers (or agents) need not necessarily maximize the firm welfare under all conditions. This stream of research on agency theory stresses the importance of setting up appropriate incentive contracts to match the objectives of the individual decision-makers with that of the firm. The contracting relationships serve as a framework in which the conflicting goals of individuals are brought into equilibrium. However, all contractual models of human behaviour have “transactional” and relational” components. The relational component emphasizes social exchange and interdependence; the transactional component emphasizes the content of mutually agreed contracts [25]. To a large extent, organizational culture, trust and relationships are part of the relational aspects. Implicit psychological contracts govern agents’ perceptions of obligations and expectations of the organization [25]. The nature of the transactional and relational contracts that govern the behaviour of the agents in the process leads to complex interactions among the other three aspects of the business process coordination mechanism. While the impact of transactional contracts on business processes is somewhat understood through agency theoretic models [30], the impact of transactional and relational contracts on KM efforts is very poorly understood. Unless the strong theoretical underpinnings of the interrelations are established, failures in KM efforts may continue to result due to a mismatch between the motivation structure and the aims of the KM efforts.

Facets of KM

While the core of knowledge is defined through the business process, the management of knowledge can be defined as a cyclical set of phases. While each of these phases can be a unique and self-contained facet of KM, it is the interactive nature of these orientations that accounts for the continuous evolution of knowledge and KM in organizations. We define the phases as the following: Storage and Retrieval, Knowledge Sharing and Knowledge Synthesis.

Knowledge storage and retrieval

The relationship between the storage and retrieval aspects of KM and the business process is symbiotic. Effective knowledge storage practices enable storing of observations, consequences, and exceptions that occur in workflow execution and decision-making activities. Most effective storage practices tend to be non-intrusive and occur naturally as part of workflow and decision-making activities. However, when knowledge storage activities are external (and artificial) to the business process context, effective control and motivational structures are necessary to ensure that the observations, consequences and exceptions are stored in the KM systems as per expectations. Furthermore, notions and concepts of storage developed from traditional data management practices are sometimes at odds with effective knowledge storage and retrieval practices.

Traditional data management practices focus on redundancy reduction as an enhancement to storage practices. However, from a KM perspective, redundancy in storage often is a facilitator to better usage and synthesis of knowledge. When these perspectives differ and reflect on the different aspects of the problem scenario and the interpretations thereof, it enhances the inquiry and problem-solving process rather than diminishing it. Therefore, while traditional data management practices emphasize accuracy through redundancy reduction, KM practices may benefit from redundant information.

Effective storage does not necessarily ensure knowledge synthesis or reuse during process execution through retrieval activities. To a great extent, this challenge in KM system usage stems from the nature of knowledge itself. In traditional data management systems, indices facilitate data and information retrieval. Storage and retrieval in data management systems mirror one another, i.e., data are stored and retrieved through the same set of indices. However, this is not necessarily the case when retrieval activities are performed in a knowledge context. Often, knowledge is stored using a set of indices (or a directory structure, in the case of documents) considered appropriate at the time of storing; but there is no assurance that these indices would be appropriate for the context within which knowledge may be retrieved. Thus, if the inefficiencies in knowledge retrieval activities are not addressed, the goals of knowledge reuse and synthesis may not be congruent with workflow execution and decision-making objectives. This incongruence would result in inappropriate use of KM systems.

Data management practices typically emphasize accuracy in persistent transactional data. However, the notion of accuracy is difficult to define in a knowledge context. Knowledge accuracy is always a function of user needs. The lack of definition of knowledge accuracy can lead to the storage of inaccurate knowledge. This is especially so when the motivational structure does not address knowledge storage or reward for contributions to knowledge synthesis through knowledge storage activities is minimal. Codified knowledge structures may address the accuracy problem to an extent by imposing rules for consistency within the knowledge structure. However, KM practices have to ensure that such knowledge structures can evolve to accommodate changes in the business process and technology environment.

Knowledge sharing

Knowledge must be shared to be useful and applicable. When codified knowledge is stored, sharing is facilitated through defined access and security mechanisms and shared semantics of the stored knowledge. In cases where knowledge, however, is not systematically stored, it becomes necessary to create communication and collaborative mechanisms to enable knowledge sharing. This necessitates intense involvement of knowledge workers in communities of practice. Codification of the knowledge domain through at least simple taxonomical structures enables the search for expertise within the social network. Knowledge sharing in this context would depend to a great extent on the motivational aspects within the process context and the cultural setting within which the process operates.

It is useful once again to draw parallels to traditional data management practices. Sharing or integrating data in traditional data management systems increases complexity (as in distributed database systems) through requirements such as simultaneous updates and locking. In knowledge-sharing systems, increased size usually increases the utility of the knowledge shared through externalities. With the increased size of the repository, structuring of data becomes a necessity for data sharing in data management systems through the relational, network or hierarchical approaches. Knowledge sharing, however, can thrive even in the absence of structure so long as a context for the shared knowledge exists. Structured data and informational focus in data sharing facilitate queries on the relations that exist within data and summarization. Informational focus in knowledge sharing contexts emphasizes inquiry where the search is opportunistic. Querying within a data sharing context has the notion of an accurate end-state (e.g., factual information). Inquiry in a knowledge-sharing context may not necessarily involve an end-state. When an end-state exists, it is usually in the form of a solution to an unstructured problem with no verifiable (and perhaps, single) true end-state.

Knowledge synthesis

The intent of storage and retrieval systems, and knowledge sharing systems is to enable and enhance the knowledge synthesis capabilities of the organization. Yet, complex interactions between the KM facets of storage and retrieval, and sharing with process coordination mechanisms may not always create conducive environments for knowledge synthesis. While workflow and information-processing aspects of business processes may create environments for effective storage and sharing practices, the decision making and motivation structure would have a critical impact on knowledge reuse and knowledge synthesis.

Rigid decision-making structures impede any innovative practices in business processes, thereby effectively nullifying the benefits of well-designed KM systems. Such processes often have to depend on innovations from outside the process boundaries. We, however, contend that KM systems have minimal impact on knowledge synthesis in processes characterized by rigid decision-making structures. Processes that emphasize contextual and interactive decision making are conducive to knowledge reuse. Such processes can use the existing knowledge stores and knowledge sharing facilities to enhance the applicability of codified knowledge and increase decision-making efficiencies. Innovations in such contexts come through novel modifications to the rules of engagement and execution to maximize process objectives. Procedural adherence can however severely limit the innovation capabilities of the process. In a similar vein, decision-making structures emphasizing meaning and order to the process encourage knowledge synthesis through evolutions in decision procedures, however, are hampered by adherence to formally defined business rules. Processes emphasizing autonomous decision-making structures present the most conducive process environment for knowledge synthesis as they are inherently designed to allow innovations in procedures and business rules. KM efforts in such processes would have the most impact in enabling knowledge synthesis through effective sharing, and storage and retrieval practices.

We use two different cases to illustrate the challenges and the attempted solutions towards KM. The cases illustrate that organizations can tailor their approach to KM by increasing the relative importance of any of the three facets of KM, i.e., knowledge storage and retrieval, knowledge sharing, and knowledge synthesis to best address specific needs. The first case details efforts in a large manufacturing organization. KM attention for this case is focused on failure analysis and failure identification (FA/FI). Knowledge storage and retrieval issues are covered as we highlight the KM challenges and approach. In the second case, we detail knowledge sharing challenges in a large public sector organization focused on health care services.

Although the knowledge management (KM) literature is extensive, the discussion on how to manage knowledge in organizations is far from having ended. Suggestions, as well as lessons learned, are continuously being put forward based on empirical studies of both successes and failures.

However, as Swan et al. [1] suggest literature published in the field, with few exceptions (see [2], [3] and [4]), shows a certain preoccupation with information technology and technical solutions while reflecting a limited view of individual and organizational knowledge-related processes. The practice of KM is commonly degraded to the implementation of new IT-based systems, neglecting important organizational aspects particularly human and social issues.

Research setting (Case Study)

To explore how KM is established in organizations, we conducted an 18-month longitudinal field study in Oticon A/S, a Danish hearing aid provider. Oticon was chosen because the company had already worked with knowledge processes during the creation of the renowned spaghetti organization (see [5], [6], [7] and [8]) the result of a major process of change that took place in the early 1990s, causing the company to migrate from a traditional, hierarchical, formal organization to an open-space, innovative, project-based, flat organization.

Oticon was founded in 1904 and based its business on importing hearing instruments from the USA. In the late 1940s, the company started its production and grew rapidly during the next decades to become one of the leading providers of hearing instruments in the world. However, in the late 1980s, the company suffered a dramatic decline in economic performance due to the American competitor Starkey’s introduction of new smaller hearing aid based on digital technology. Oticon’s market share dropped from 14% to 9% and the board consequently chose to employ a new CEO. Based on the vision of “think the unthinkable”, he introduced a new project organization [5] and [9] which turned four aspects of the organization upside down: (a) jobs were designed to fit the person’s capabilities and needs, and all employees were encouraged to engage in at least two functions; (b) the formal hierarchy and titles were abolished; (c) the traditional office disappeared and all employees, including management, were provided with a trolley on wheels for their documents and personal belongings to enable project members to sit together for the duration of a project; and (d) communication was digitized by scanning all incoming letters and making them available to the organizational members.

IT accordingly played a very central role in the organizational change process. The vision, which was subsequently implemented, was to create a paperless office equipped with identical workstations to which employees could log on with their personalized profile, regardless of which workstation they used. In this way, the IT infrastructure supported the aim of creating a flexible workplace where employees were free to move around according to their current assignments. To store all documents, including incoming mail which had been scanned, a document management system was developed which gave all employees access to shared electronic storage [33]. IT was given a central role in the change process, but it was a facilitator rather than a driver of change. It was the general understanding among employees in Oticon that any KM initiative had to be based on the fact that people, and not IT systems, share knowledge. IT was consequently seen as enabling knowledge creation, sharing and use, but it had to be combined with and support organizational initiatives.

Although the spaghetti organization was described as a knowledge-based organization in the vision, management did not initiate a particular KM strategy or project.

The study followed the organizational members’ efforts to establish KM between Oticon’s headquarters and the downstream value chain partners (i.e., the regional sales companies and the local hearing clinics, which are referred to as dispensers of hearing instruments). The primary focus for the fieldwork was to explore the members’ meaning construction and understanding of the process of establishing KM as well as how the members’ meaning construction and action influenced the process over time. As the focus was on the process of establishing KM, the actual product or outcome of the process was of less interest.

The first KM activity which we followed in the field study, KiteNet, was intended to map knowledge flows in the downstream value chain. It was put on hold due to resource problems. In parallel, we found that, although there was no formal KM project, various KM related initiatives sprouted in different parts of the organization. On reflection, we realized that we had focused too much on finding the one formal project to follow. KM in Oticon consisted of a range of autonomous, bottom-up initiatives. Examples of these initiatives were intranet-based knowledge sharing systems for marketing and sales information, an Internet-based shop and information site for the retailers (Professional Corner), an initiative to provide journalists and potential customers with information to promote a new product (Digilife.com), an attempt to create an in-house KM consulting unit to enhance the downstream value chain partners’ knowledge about products and services, and a project to enhance the use of knowledge coming from the value chain partners to facilitate better budgeting, and to offer them more relevant services according to their specific needs. This realization led us to an adjustment of the research focus to take a closer look at the KM-related action that was taking place at Oticon without being part of a formal project.

Reflecting on this changed view on the process of establishing KM, several puzzling questions emerged from the fieldwork. Why were there so many activities characterized as KM-related that were related, but not formally part of, any KM project? Why did the members keep coming up with new ideas, proposals and experiments with information systems solutions when previous ideas and solutions were not supported by management? And finally, what caused this mismatch between the level of activity by the members and management’s reluctance to support the activities?

In brief, we discovered that the process of establishing KM at Oticon was indeed very interesting, and it raised some pertinent questions that could provide important insight into how KM unfolds over time if it is not a top-down and planned process. Based on this altered conception, we pursued a grounded theory study of establishing KM as a bottom-up process.

The ontological and epistemological assumptions of the study are informed by the interpretive paradigm, and accordingly, the role of the members is understood as active constructors of meaning as well as active interpreters of reality. The members’ meaning construction process is central and forms the basis for understanding the members’ actions. Drawing from symbolic interactionism [10], the meaning construction process is seen as occurring in social interaction between the members. Moreover, the study adopts a social constructivist view of reality, implying that reality is socially constructed by the observer [32].

The research approach of the study is inductive and based on a strong empirical foundation on which new theoretical insight into KM as an autonomous action is created. Specifically, the study uses an adapted version of grounded theory [11], also referred to as constructivist grounded theory [12]. Its two processes, discovering and emerging, are understood as covering a meticulous interpretative process in which the resulting concepts, and eventually theory, are constructed. In other words, we do not seek the truth as universal and lasting, but we see the research product as a rendering or one interpretation among multiple interpretations of a shared or individual reality [12].

Data collection

The data collection was based on multiple sources and focused on the process elements of context, actors and actions [13]. In general, questions about KM actions (including activities and events) were pursued first, and they usually led to information about the context for the KM actions and the organizational members involved. General topics such as company strategy, social structure, management, history, and environment were covered to serve as background information. Cognitive issues regarding the members’ perception of the organization as the context for their behaviour and that of management were also pursued. Three sources provided the majority of the data for the study of KM in Oticon: participant observation, interviews and archival documents.

Participant observation was mainly carried out throughout the first year of the field study, with one researcher spending approximately 3 days a week at the company, where she was provided with a desk and participated in relevant meetings and discussions. This time spent at the company enabled them to gain a familiarity with the company’s culture and its informal structure. The participation also encouraged trust-building between the researcher and the organizational members, which again helped to gain information about the members’ perception of the company and management. The interviews were unstructured as well as semi-structured, each lasting from approximately 1.5 to 2 h. In addition, data were collected through many ongoing conversations, the duration of which cannot be specified precisely. Some of the favourite topics of the key informants were discussed repeatedly during the field study. A total of 18 people were interviewed, some of whom were interviewed 10 or more times. As Oticon’s corporate culture did not encourage the members to spend time on creating memos or notes, the archival documents were of less importance than the other two means of data collection. Finally, academic as well as more popular literature about the Oticon case has been a valuable source of information.

The members at the operational level, who created the KM-related actions, have been the primary informants in the field study, and the insights about the process of establishing KM provided by the study are based primarily on their experiences, understandings, and feelings of and about the process. Their mutual interactions as well as their interactions with management were observed. However, some members of management were also interviewed.

Data analysis

The data analysis was conducted using a grounded theory approach. As grounded theory is used within different research traditions based on different epistemological assumptions, we find it important to emphasize how it is used in this study. Acknowledging the positivist leanings of the original authors [11], we have used a later adoption of the theory by interpretive researchers which stress that theory does not emerge from data, but data are constructed from the many events observed, read about or heard about [12], [14] and [15]. The interpretation and recasting of the data in analytical and new terms involve the actors’ as well as the researcher’s interpretations [15]. From an interpretive perspective, the term emergence, therefore, covers a meticulous interpretative process including the construction of concepts.

The analysis was conducted in a four-stage process that spanned the entire study. Firstly, we named and compared incidents, identified concepts and discovered their properties, similarly to what Strauss and Corbin [15] refer to as open coding. Then we integrated the concepts and categories to build the first skeleton of a theory. Thirdly, we reduced the number of categories, delimiting the theory, to identify the most relevant and robust categories to form a story. Finally, we presented the data and the results in the form of a narrative and a model for understanding the interrelationship between the members’ meaning construction and behaviour in the process of establishing KM.

In line with the view of reality as socially constructed, we do not claim objectivity, but instead, we argue that the emergent theory is one of several possible explanations of reality constructed with the researchers as active instruments. The theory or explanation reflects the viewers as well as the viewed. This does not mean that all explanations are equally relevant, credible and acceptable, but that it is up to us as researchers to argue the case for the explanation which we want to present.

Empirical findings

The findings from the analysis are presented in the following subsections. Firstly, the unfolding of the process of establishing KM is explored in more detail to explain the different foci and actions, and what the key characteristics of the KM initiatives were in the different periods of the process. Secondly, the concepts and categories from the grounded theory analysis are presented and discussed in more detail to present the skeleton of our process model of establishing KM. Thirdly; the theoretical frameworks which contributed to the refinement of the analysis are presented. Fourthly, a stepwise movement through the model will provide detailed insights from the analysis as well as clarification for the relations between the members’ behaviour and their meaning construction that led to the failure of formally establishing KM at Oticon.

Periodization: three dominant expressions in the process of establishing KM

Throughout the fieldwork, the course of action constantly changed, and it is thus an approximation when we refer to “the process of establishing KM” as if it was a single coherent process. Here, the complex nature of the process is emphasized by dividing it into three different periods, each with its focus. Even this is an approximation, as the periods are not specified or separated. However, this rough division helps to show the continuously changing nature of the process. The periods are closely related to the key members at a specific time in the process, but the general discourse on KM and the experience gained from previous KM actions also contribute to the creation of a specific focus at a given time. The three periods and their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. It is important to note that the labels for the periods refer to the dominant focus in each period, but that all three periods contain the different foci in part. Instead of thinking in terms of separate periods, it is more appropriate to conceptualize the three labels as coexisting manifestations of the KM understanding and practice in the organization, more or less dominating in the different periods.

Knowledge management as information systems

In the first period of the field study, the IT function spearheaded the process intending to create a knowledge infrastructure based on an expansion of the existing intranet, KiteNet. This new knowledge infrastructure was seen as a natural development of the knowledge-based organization. The dispenser-targeted service Professional Corner, which was developed in collaboration between IT and Marketing, was central for the focus of KM in this period. It was developed as an initiative aimed at creating value-added services to hearing aid retailers via the Internet. Several components were to be included, for example, an event planner to help dispensers plan their campaigns, a news system, an order tracking system, and a marketing material download service as well as a product catalogue from which dispensers could order new supplies. During the design and development of the system, it was decided to use a technological solution based on the ERP system, which Oticon had chosen as the company standard. This decision contributed to shaping the functionality of the system and emphasized the ordering facility through which the sales companies could place their orders.

The members saw this focus on information systems as drivers of KM as a natural extension of the IT infrastructure to include the downstream value chain in the knowledge-based organization. In retrospect, IT’s central role in this period might also have been a result of the general perception of KM, which in the late 1990s was dominated by the conviction that knowledge could be stored and reused by the use of IT.

In this period of the process of establishing KM, the focus was very much on the use of the intranet to facilitate knowledge sharing in the value chain, where people in physically distant locations would be able to communicate and share information. The use of the intranet was also based on the expectation that it could work as the great unifier, integrating existing IT systems. Finally, people in different parts of the organization had planned or worked with intranet functionality and content. The understanding of the intranet was accordingly widespread in the organization and not concentrated in the IT function, as was the case with other more specialized systems.

From an IT perspective, the process of establishing KM can be seen as a step in the development of more advanced uses of the intranet [16]. The intranet, as well as the Internet, were indeed seen as enabling technologies for the development of collaboration and a crucial element in Oticon’s KM initiative, although the general understanding among the members was that technology needed to be combined with organizational initiatives to work.

Although there was a general agreement about the relevance and need of a KM system to strengthen the collaboration between the value chain partners, IT and Marketing—who were the key stakeholders in the process—did not agree on the functionality of the system. The IT function worked on an integrated holistic solution based on the concept of a central repository containing all information needed by the target groups. Marketing argued that this was too complex and time-consuming to establish. Instead, they suggested that emphasis be put on creating smaller-scale solutions which could be launched immediately. This disagreement shifted the focus and the effort of the involved parties from development to discussions about the architecture and functionality of the system. Management did not actively support or reject the KM initiatives, and eventually an increasing resignation among the members who had previously invested significant time, energy, and enthusiasm in the process set in.

Knowledge management as an organizational practice

The period of promoting IT to enable the storing of knowledge was followed by a period of refocusing on the organizational practices of knowledge sharing. This process encouraged activities with representatives from the sales companies, intending to get people from the value chain together to form relationships and to exchange knowledge, thereby enabling new ways of communicating and sharing knowledge. These activities, which one of the members referred to as “[put] people together in a room and then close the door and hope that something comes out of it,” were not a very structured approach, but rather a way of facilitating knowledge sharing “without making a big fuss about it”.

A sales and distribution project also emphasized routines for knowledge sharing and proposed a set of more structured routines to gather knowledge from the downstream value chain in the form of more elaborate and structured budget forecast feedback from the sales companies, as well as more stable facilities for offering support and promoting new ideas to the parties in the value chain. It was suggested that a business team that could provide the necessary sales support to the sales companies on non-product related issues be established.

Although IT played a less important role in this period, both marketing and the IT function were still highly engaged in creating and implementing information systems for managing knowledge in the downstream value chain. In contrast to the previous period, implementation issues and the organizational practices supporting the use of the information systems had become a key concern. A member talked about “creating a contract where the sales company has to commit itself to spend a certain number of hours on implementing the system and educating the users. We thereby ensure that they don’t just call us and say that the system doesn’t work”.

Knowledge management as process integration

The third period in the process was characterized by a downscaling of KM activities. Although some of the activities were still in action, attitudes about KM had changed. Previously, KM activities had been promoted as separate activities happening alongside and in connection with the organization are other activities. Now the main emphasis changed to focusing on and promoting KM as integrated into the core processes of the organization. An employee expressed this when she commented that “Knowledge management is not an issue in itself. It’s just a natural and integrated thing—something we do all the time”.

This downscaling of KM as a topic on its own can be seen as a consequence of the lack of support for the previous KM ideas and activities. It can thus be interpreted as an attempt to adapt the idea to what was perceived by the members as the corporate strategy to better “sell” the idea to management. This is supported by a comment from one of the members who said that “by making it [KM] an integrated part of what we do anyhow, it has become easier for management to understand the value of it, and thus easier to get support for it”.

The three different expressions of KM presented above clearly show that the process did not have a consistent, stable focus, but changed over time according to who participated, what activities or events took place and the context in which the process unfolded. Started as a bottom-up initiative, the process of establishing KM never really managed to gain support from management, and it eventually changed into a set of less new or radical ideas for organizational change.

Conceptualization: creating the basic building blocks for the process model

The main concepts that emerged from the analysis are presented as a first step to categorize the empirical findings, and thus to construct the basic building blocks for building the grounded theoretical model. We identified three main categories: KM venturing, action attitude and perceived managerial inaction which are described below.

KM venturing

The first main category, KM venturing, refers to the process of establishing KM as a member-driven start-up process, which emerges and develops outside the scope of the current corporate strategy in Oticon. The process consists of three sub-processes, each referring to a period in the process of establishing KM: creating, negotiating, and formalizing.

In the creating process, different activities, events or ideas were created through innovation processes or adaptation or adoption of ideas existing outside the organization. The creations were primarily spurred by personal interest and done in parallel with other work tasks. Management’s involvement with the activities was limited, and human or monetary resources only sporadically fuelled the activities. The organizational members themselves described their efforts as “skunk work”. The creating process was unstructured, and members from various functions were involved. The mood was one of enthusiasm, and the activities were driven by the urge to “try this out” or “make this happen”. When asked about the appropriateness of spending time on activities that were not supported by management, the members generally stated that being at the forefront and trying out new ideas was a part of their job, and what had attracted them to Oticon in the first place.

Following the process of creating was a process of negotiating the new ideas and activities. This unstructured process, similar to the creating process, was initiated by the members. The ideas and activities were shaped into more coherent ideas or proposals by the members, who then subjected them to what they imagined to be a decision-making process in which they supposed management would decide which ideas should gain support in the form of resources or attention. The members “argued” for their case and “insisted” on the value of their ideas for the organization, but at the same time “uncertainty ruled”, and the members referred to management as being “indifferent” and “not treating new ideas seriously”. The uncertainty also showed in the negotiation process, which exposed the “lack of consensus” about what should be prioritized in the process of establishing KM. The members referred to this process as “highly political” and a source of internal “conflict”.

The formalizing process differed from the other two sub-processes by being a future process, or stage, which was important for the members as a presumption or idea of how the process would develop. In this presumed process, the activities and ideas for which the members had managed to gain support were to be made into formal projects either by being given a formal status or by receiving financial support from management.

The new activities or ideas that management decided to support were to be integrated into other relevant projects or processes in the formalizing process, and would thereby become part of the organizational routine. Throughout the fieldwork, very few ideas and activities were supported by management, and the majority of the activities that were studied as part of the KM initiative were either renegotiated, recreated or dropped, and never became formalized.

The name venturing for these processes connotes not only innovation, creativity, new ideas, and opportunities, but also the act of choosing among the various creations, and finally building or learning something new. By referring to the process of establishing KM as a venturing process, we emphasize that it is not a top management driven process, but an initiative driven by organizational members based on their beliefs in its potential to benefit the organization and not by the overall strategy of the company.

Action attitude

The main category of action attitude, the members’ attitude to KM action, emerged from the data as a puzzling question of why the members persisted in creating new ideas and activities regarding KM in the value chain when the activities were continuously neglected and ignored by management. This persistent action in the process of establishing KM showed in the members’ continuous attempts to propose new action in the form of ideas, activities or systems, to rethink already existing action, to adapt previously rejected ideas, or to engage in long and tough battles for the proposed KM action. When asked why they continued to pursue the KM action, several of the members acknowledged that it might be difficult to understand for outsiders that they pursued what seemed to have already proved to be a dead-end, but they explained it by referring to Oticon as a special organization “where you have to fight for what you want. If you show signs of weakness, you will never get anything through.” There was a general belief among both employees and managers that possession of certain personal attributes was important to fit into the organization. Among these were “self-promoting”, “determined and courageous”, “not too shy or quiet”, or even the need to be “‘stand on the table and shout’ types”.

Many references were made to the characteristics of the spaghetti organization as “front running”, “daring”, “inspiring” and “interesting”. The image of the organization as creative, innovative, open and flexible proved to be important for the members’ persistence, and it thus became clear that the interplay between meaning construction and action was important in explaining the unfolding of the process aimed at the establishment of KM.

References to the structure of the organization also helped to build this category. The high degree of informality with “no departments or titles”, “no hierarchy”, “a network of experts”, and the opportunity to “form one’s job” contributed to the organizational members’ attitude to action, as did the ambiguity referred to as “chaos” and “confusion”.

The physical structure of the buildings supported the characteristics of the organization as open and non-hierarchical by providing open space offices, one lunchroom for all employees, and glass walls in meeting rooms. The importance of being visionary was underscored by a set of Greek pillars with the inscription “cogitate incognita” (Latin for “think the unthinkable”).

The main category of action attitude is not an unequivocal concept but expresses the members’ attitude to the KM action, which changed during the field study from persistence to renouncement. The category of action attitude is thus used to cover both the persistence and the renouncement of the action.

Perceived managerial inaction

The third main category, perceived managerial inaction, emerged as a characterization of the members’ interpretation of management’s role, which changed during the process of establishing KM. The category constitutes a perceived reality to which the members interpret and respond, and which influences their actions as well as being influenced by their actions. Managerial inaction is therefore not a category meant to explain the actual action of management. Instead, it contributes to explaining why the members’ attitude to action changed over time from persistence in the creating process to renouncement in the negotiating process.

According to the members, management was only briefly involved in the process of establishing KM and spent very little time discussing the issues with the members who proposed them. The members’ interpretation of this inaction changed quite radically during the process. In the creating process, the interpretation of the managerial inaction was that of facilitating the process by “enabling the employees to use any talent” and make “as few regulations as possible”, whereas in the negotiation process it was that of inhibiting the process by “letting the KM initiatives linger.”

The organizational members’ perception of a “lack of support and attention” for their KM initiatives from management contributed to building the main category of managerial inaction. They described management as showing “disbelief” and being “aloof”. Moreover, the misalignment between their expectations and their experiences of how management should receive their proposals for new KM initiatives created a growing feeling of “uncertainty” about management’s interests and priorities, which again resulted in the questioning of the meaning behind management’s inaction.

The members explained their reinterpretation of the concept as based on changes which they had experienced in the values originally promoted by management as a foundation for the spaghetti organization. Now they mentioned that “action rather than talk” was a priority, and “results—not highflying ideas” were encouraged. They also mentioned management’s focus on products as opposed to visions and organizational development which were supported by management’s decision to focus on “only product marketing—no concept marketing.”

Like the concept of action attitude, the concept of managerial inaction is equivocal, as it covers both the organizational members’ perception of managerial inaction as facilitating and inhibiting the KM initiatives. In the period where the organizational members interpreted the non-intervention as organizational slack, the managerial inaction was perceived as facilitating, and in the period where it was interpreted as indifference, it was perceived as inhibiting.

Theorization: presentation of theoretical input to further explore and develop the model

Once the findings had been explored in-depth and the theory was taking shape, we returned to the literature to compare the findings and to look for relevant theoretical contributions to the analysis and discussion of the data. Before introducing the grounded theoretical model, we therefore briefly present the two theories from which we have drawn in the construction of the model.

Burgelman’s framework of the strategy-making process

Burgelman’s framework of the strategy-making process [17] and [18] served as an analytical tool for exploring and explaining the unfolding attempt to establish KM in Oticon as an autonomous strategic action initiated by operational-level members outside the current concept of strategy—in other words, a venture process. By drawing from the framework, we were able to reflect upon our findings from the field study and challenge our grounded concepts and categories [14].

Burgelman’s framework presents an evolutionary understanding of the strategy process as unfolding in the three phases of variation, selection and retention, where the last phase is the company’s current corporate strategy. The variation phase consists of two types of action, induced and autonomous action. Induced strategic action resembles the traditional top-down view of strategic management and is oriented toward gaining and maintaining leadership in the company’s core processes. Autonomous strategic action, on the other hand, is driven by impetus from the bottom of the organization rather than plans. In this framework, the process of establishing KM in Oticon can be seen as part of the organizational members’ autonomous strategic action, as the majority of the KM activities fell outside the company’s current corporate strategy. There was no induced action in the process, as management did not actively initiate or support the KM initiatives.

The framework presents two selection processes for linking the strategic action to the corporate strategy: strategic context and structural context processes. The strategic context processes determine what autonomous action should become part of an organization’s corporate strategy. They involve reflective learning and the cognitive ability to put the outcomes of internal and external selection in context [18, p. 112]. They are not driven by rules but are cognitive and political processes aimed at making sense of highly equivocal inputs to establish the potential of new ideas and actions to become part of the corporate strategy.

The structural context processes comprise mechanisms that top management can use to ensure a link between the induced strategic action initiated in different parts of the organization and the corporate strategy. These mechanisms include rules, values, work processes, structures and company history in general, mechanisms that entail a stabilizing force on the strategic actions as they facilitate the creation of new action as a continuation of current activities as well as influencing the strategic context determination for the autonomous action. In our case study, the structural context process was changing from being highly influenced by the spaghetti way of thinking and organizing to becoming a more traditional, less innovative organization. This change in focus or priorities influenced management’s will to support the autonomous KM actions, as will be discussed below.

In addition to the framework, we also drew from Burgelman’s process model of internal corporate venturing [19], which provides insights into the strategic leadership activities involved in managing the autonomous strategic action of a company. The process model complements the framework of strategic action by focusing on the roles and more detailed activities of project management, senior management and top management. The activities of the three levels of management are described in two sets of processes: (1) definition and impetus processes, in which the idea is created and takes shape, and (2) the strategic and structural context determination processes, where the idea is challenged and its usefulness as part of the company’s future strategy must be proved.

In strategy research terms, Burgelman’s process model provides a micro-level view of management’s strategic activities (induced as well as autonomous) in the venturing process. Although the model does not document the activities of the operational-level members in the venturing process, in the study of the process of establishing KM it is helpful to understand the various activities in which the members took part. The activities documented in Burgelman’s process model also contributed to the understanding of the empirical data from a management perspective, which was not the focus of this research study.

Weick’s concept of sensemaking

Since the empirical data showed that the process of establishing KM unfolded in the interplay between meaning construction and action, Weick’s [20] concept of sensemaking was applied to explain how members made sense of the action and behaviour of management. In Burgelman’s framework, the influence of meaning construction on the selection of autonomous action is briefly mentioned but is not explored in detail. Weick’s concept of sensemaking is used to provide insights into the interplay between the organizational members’ meaning construction and action, and thereby complements Burgelman’s model of the venturing process, which is primarily aimed at explaining the role of management.

Like the framework of strategy making [17], sensemaking is informed by evolutionary theory and is closely connected to the process of natural selection. This does not make sensemaking a strategic process, and Weick [20] explicitly mentions the rational view of strategy as being in direct opposition to sensemaking. But as the understanding of strategy in the Burgelman framework is that of strategy as emerging and not rationally planned, the two frameworks are based on similar assumptions and they are thus not opposites, but supplement each other.

Sensemaking is an ongoing process of meaning construction, and meaning is understood as a product of the sensemaking process. The creation of meaning is a cognitive process that links an experience to a context, and it thus corresponds to the process view that guides the study of the process of establishing KM. Although sensemaking is a cognitive process, it is also closely linked to action, which precedes the construction of meaning and makes sensemaking a retrospective activity [21].

To analyze the members’ meaning construction in the process of establishing KM, we use four of the basic concepts in sensemaking: enactment, constructed or construed realities, bracketing, and self-fulfilling prophecies.

The process of enactment explains how people create the environment which impinges on them, which is a basic assumption of the sensemaking process [21, p. 5]. In the process of enactment, people draw from collective maps [22] or construed realities [23] and [24]. A construed reality is an assemblage of more or less connected pieces of information and beliefs which together form a picture that confirms or constructs a reality [23]. When people enact a construed reality, their noticing and interpretation of information and experiences are done by the construed reality. Weick refers to this process of “pulling out” portions of these experiences in the continuous flow of information as bracketing. The purpose of bracketing is to reduce ambiguity and to cope with the vast amount of information and experience which we encounter or notice every day.

In the process of establishing KM, the members created two different realities (see Section 4.4.) which they enacted in the different periods of the process, and which led to different understandings and actions. We interpret the members’ attitude to action in the first part of the process of establishing KM as a self-fulfilling prophecy, which is described by Weick as thinking in circles [21, p. 159]. A self-fulfilling prophecy is created when people act on their interpretations (self-created reality), and others take notice of them and interpret them equivalently to those of the original actors, and then act on these interpretations in ways that verify the original interpretation, thus amplifying the original interpretation [20, p. 79]. In the analysis of the process of establishing KM, we interpret the change in the members’ understanding of management’s responses to their actions as caused by a “shock” [20, p. 84] based on the members’ uncertainty of how they should understand management’s actions. While sensemaking is a continuous process, it can intensify on occasions where an unexpected experience creates a gap between the way things are and the way they should have been. According to Weick [20, p. 91], there are two types of occasions that can cause a shock and thereby initiate an instance of sensemaking in organizations: ambiguity and uncertainty. Ambiguity is the situation where “the assumptions necessary for rational decision making are not met” [20, p. 92]. The problem here is not that information is insufficient, but that more information may not resolve misunderstandings, but instead create confusion. Uncertainty, on the other hand, governs when there is a lack of knowledge, i.e., ignorance. In our study, we analyze the collision between the members’ expectations and experiences as such a shock created by ambiguity which can explain the reconstruction of meaning which happened in the course of establishing KM.

By drawing on the concept of sensemaking and the framework of strategy making in the analysis, we can analyze the interrelationship between action and meaning construction in the process of establishing KM. Where the framework of strategy making is used in the analysis to explore the KM action, the sensemaking perspective helps address the cognitive issues in the process of establishing KM and provides some important insights into how the members construct meaning as well as how this meaning construction shapes the process of establishing KM, which will be described in the next section.

A grounded theoretical model of the process of establishing KM

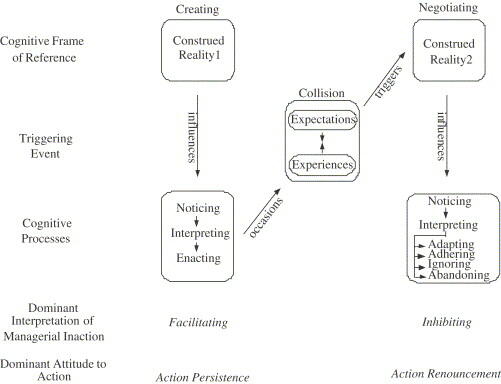

As a result of the initial analysis and conceptualization based on the two theoretical frameworks, we developed the grounded theoretical process model of establishing KM. The model in Fig. 4 shows the KM establishing process as unfolding in the two sub-processes of creating and negotiating. As mentioned before, the process of establishing KM never came as far as being formalized. The process model consequently only comprises the two periods of creating and negotiating. The model shows how the members’ meaning construction and action interact and develop in these two periods, and how this affects the unfolding of the process.

Creating the knowledge management action

In the first period of creating, the members’ general understanding of the organization—the construed reality of “thinking spaghetti”—dominated and influenced the KM action. Thinking spaghetti was a strong organizational identity and structure, which was created during the major change process in the early 1990s, but which was still very strong during our study.

The members referred to the organization as being special, different, and unique. This is illustrated by the following quotation from our data: “It’s a great place to work. You don’t have a boss constantly looking over your shoulder and you have lots of really competent and inspiring colleagues.” The members praised the openness and trust which they encountered and which they attributed to the creative, daring and front-running organization.

The action in this first period of creating was characterized by a high level of activities and ideas related to KM, proposed by different members from different parts of the organization. Concurrently, they referred to the organization as Darwinian and jungle-like as mentioned by one of the members: “This is a true Darwinian organization. There is a finite amount of resources and only the ones who … can substantiate and justify the need for more resources … get the resources in this organization.”

Based on the members’ perception of the organization as a creative environment that encouraged new ideas but also demanded that you had to fight for the ideas, various KM activities were initiated. The members saw the KM initiatives as a natural extension of the knowledge-based organization and did not doubt the support of management. Although they noticed the inaction of management, they interpreted it according to their perception of the organization as innovative and management as non-interfering to facilitate the initiative of the employees. Instead, they worked even harder to convince management to pursue the KM initiatives, and when they failed they blamed their inadequacy to create proposals that were good enough. In this way, their action was framed by their perception of the organization and they continued to propose new KM initiatives based on thinking spaghetti. In time, however, the members experienced a growing dissonance between how they expected management to act and what they experienced, which caused the collision between expectations and experiences which are shown as the intermediate phase in the process model.

Collision

The transition from the process of creating to the process of negotiating was triggered by a collision between the organizational members’ expectations and experiences which made them reconsider their assumptions about the organization and how they should interpret the inaction of management.