Introduction

Overview

The process of evaluating the performance of an organisation requires the use of a number of parameters. Benchmarking is one of the commonly used performance indicators across the globe today. The main aim of this approach is to help compare the status of a given entity with that of the best firms operating in the same industry. The process focuses on three major aspects of an organisation. The elements include cost of goods and services offered, their quality, and time taken to deliver them to customers. According to Camp (1989), benchmarking outlines specific details touching on a company’s operations.

It also indicates the details that enable the company to realise its objectives. Benchmarking gives rise to a number of key performance indicators, which outline an organisation’s strengths and weaknesses. To this end, the success of benchmarking is based on how well the performance indicators are depicted. In the current paper, the author outlines various contemporary issues with respect to benchmarking at the Intercontinental Hotel Group.

Background

Benchmarking is mostly carried out in cases where organisations need to improve on certain areas. To achieve this, there must be efficient utilisation of the resources available. The resources include labour, land, and capital. The same is realised when a company decides to adopt operational policies from a different entity. Benchmarking takes a specific orientation given that the performance indicators reflect how an organisation is fairing in its operations (Henderson-Smart et al. 2006).

In most cases, financial statements are designed to include such indicators as cash flow statement, balance sheets, and income reports. Detailed financial reports provide additional information that elaborates on the respective performance indicators. There are emergent issues in the area of financial reporting, which strengthen the benchmarking of a given company.

The hospitality industry is regarded as one of the fastest growing sectors in the world of business. The sector thrives on disposable income in the economy. It also relies on the growth of the middle income group. The availability of leisure time has also led to the continuous growth of the industry. According to Alinyo (2013), there is an increase in the volume of travels around the world. Analysts predict increased rate of travel in the future.

The implication is that the hospitality industry is bound to grow more. More organisations are also likely to invest in the sector, leading to competition. To this end, there is a need to ensure that the quality of services offered is maintained. Organisations operating in this sector will need to offer services that are of high quality in order to attract customers. Benchmarking is one of the practices that can be used to achieve this.

In this paper, benchmarking is discussed with respect to the Intercontinental Hotel Group. The company is a global franchise whose growth depends on best practices. It operates over 4,600 hotels in more than 100 countries across the globe. As such, it is considered as one of the best companies operating in the hospitality industry. The entity has a number of world class hotel brands, such as Hotel Indigo. According to Alinyo (2013), the organisations within the hospitality industry depend on quality of services to meet core operations. Benchmarking ensures that companies remain competitive in the market.

Rationale of the Study

The current study focuses on benchmarking, specifically in the hospitality industry. It identifies the leading firms within the industry and compares their operations with those of the benchmarking organisations. The processes carried out by the firm that is being benchmarked are compared with the results achieved.

Benchmarking seeks to improve the performance of firms by helping them adopt policies and practices that are beneficial to others. The process also identifies why a firm is successful. The rationale for this study is informed by its relevance to the industry, as well as its scholarly benefits. According to Elmuti and Kathawala (1997), benchmarking allows for the evaluation of the performance standards within a given organisation. Once the standards are identified, they are shared across other organisations.

Following are the justifications of this study:

- To enhance the comprehension of the concept of benchmarking

- To outline the process of benchmarking.

- To illustrate how organisations can share information on operational growth.

- To illustrate how organisations can best analyse and utilise information gathered during the benchmarking process.

- To establish benchmarking trends within the hospitality industry

- To outline the regulations within the benchmarking process

The findings made in this study can be used by stakeholders within the hospitality industry. According to Milohnic and Cerovic (2007), businesses have a great deal to learn from the benchmarking process. A lot of positive outcomes in terms of performance are expected from the incorporation of the best practices in the industry learnt from the benchmarked firm. The study will increase the information available about the subject. Findings from this research paper will enable stakeholders in the hospitality industry to establish the best benchmarking practices.

Structure of the Paper

The paper has three main parts. The first provides background information, introduction, and the literature review. In this section, the author examines some concepts about benchmarking. The introduction lays the foundation of the study. Previous studies on the subject are outlined in the literature review section.

The author examines key aspects of benchmarking process. The literature review also examines key performance indicators. Part B contains the results and analysis of data pertaining to benchmarking in the hotel industry. The results are compared to the information in the literature review. A comprehensive discussion is provided in Part C, followed by recommendations and a conclusion.

Literature Review

Benchmarking

Benchmarking is a continuous and systematic process of evaluating specific parameters of a company and its performance. The parameters evaluated include products, processes, and outcomes. The evaluation is carried out in comparison to those in other organisations that have recorded success in their operations.

Benchmarked firms in most cases are the best in the industry. The benchmarking organisation targets to structure its operations to reflect those of the target firm with the hope of attaining similar outcomes. According to Edith Cowan University (2011), the process is used in various organisations to improve performance. The outcomes depend on the ability of an organisation to identify and implement the best practices.

Quality Assurance (QA) is another element of business that evaluates the performance of an organisation with respect to specific functions of production. It aims at preventing the production of goods that are substandard. For service provision organisations, such as those in the hospitality industry, it ensures that minimal problems are encountered. The practice is mainly aimed at benefiting the consumers of the final goods and services as opposed to the organisation undergoing quality assurance checks.

The study by Henderson-Smart et al. (2006) points out that QA and Benchmarking are not the same concept. Henderson-Smart et al. (2006) argue that benchmarking focuses on minimum but acceptable standards and compliance. In most cases, such standards are enforced by regulatory agencies or internal management. Quality assurance on the other hand seeks ensure that the highest standards are adhered to during the production of goods and services. Unlike benchmarking, the practice is carried out by an external party and the internal management has no option but to adhere to the laid down quality control procedures.

Factors Affecting Benchmarking

Available literature indicates that benchmarking is applicable to the hotel sector and the larger hospitality industry. A study by Nassar (2012) illustrates that benchmarking is a contributing factor to performance in the hospitality industry. Notwithstanding the influence of this process in the industry, there are several performance elements that enhance its. The factors affecting benchmarking call for an understanding of the various types of this strategy.

Min and Chung (2002) used an empirical study to carry out external (competitive) benchmarking to prove that dynamic benchmarking can be used as a service improvement tool in hotels. The researchers used two key dimensions, guest room values and front office service attributes, to determine “best practice” among Korean luxury hotels in a study carried out in Seoul, South Korea, in 2000.

Findings from this study indicate that the most important attribute in determining quality is cleanliness of a guest room, followed closely by courtesy of employees, serenity, handling of complaints, and comfort.

The study also found that due to increasing competition in the industry, hotels need to continuously improve standards by applying dynamic benchmarking to achieve service excellence. Benchmarking helps hotels to see how their competitors are doing business and borrow some of the best practices in the industry. Following the benchmarking process, a firm can identify some of the hindrances to success.

A hotel company can also be able to implement already tested practices. As such, there will be minimal risks on investment by the company. With benchmarking, a firm can also be able to identify new technologies that can help them upgrade its operations. For example, hotel companies up on determining the effectiveness of software used in the regulation of services, such as booking can implement the same.

In a separate study, Nassar (2012) sought to investigate the current state, understanding and opinions of benchmarking in the Egyptian hotel sector in order to establish perceived benefits, obstacles, and possible improvements. The researcher used the descriptive approach with a structured self-administered questionnaire to conduct the research.

Findings reveal the current benchmarking practices in three major areas. According to the research, most hotels in Egypt have benchmarking experience regardless of their location or size. The hotels demonstrate a positive attitude towards benchmarking and perceive it to be a useful tool in assessing best practices in the industry. Leading firms in the industry are not opposed to the practice by other smaller or less successful organisations. As such, the process has become a common practice in the industry.

The two studies (Min & Chung 2002 and Nassar 2012) employed empirical research, which involved observable phenomena. According to Min and Chung (2002), the specific service metrics used are comparable across the hospitality industry and in other service settings, such as hospitals and the banking sector. The findings confirm the views of the people in the industry that benchmarking improves services offered by firms. As such, it makes it easier for them to compete with the market leaders.

Nassar (2012) addresses attitudinal issues with regards to awareness of the benchmarking concept in the hotel industry, which can be influenced by culture. What this implies is that these studies can be replicated in other industries and regions where results may vary due to cultural differences. Nevertheless, these empirical research findings are consistent with those of a conceptual research by Elmuti and Kathawala (1997).

Advantages of Benchmarking

Benchmarking transcends competitive analysis. It is more of how companies can acquire information regarding certain processes. To this end, the concept of benchmarking viewed is an integral aspect in the day to day running of a company. Many studies have also viewed benchmarking as a continuous process. The hospitality service delivery industry is dynamic. Firms operating in the sector are bound to change their mode of doing things constantly in order to remain competitive.

Hotel companies must therefore be vigilant in their quest to gather new information on how to improve their operations. Benchmarking is one of the easiest and most effective way to gather this information. The reason behind this is that the process seeks to identify the best practices within the industry. The practices are already tested in the firm that is to be benchmarked and the results of its application can be quantified.

There are a number of studies which outline the importance of this construct. For instance, Lyonnais (1997) suggests that benchmarking allows organisations to outperform competitors. To achieve this, Omachonu and Ross (1994) state that a firm needs to be vigilant to identify the practices that help competitors perform better. A firm has the option of adopting similar practices or improving on those of others to outperform them. Benchmarking must not always be done in a firm that is operating in the same industry.

However, the farm being benchmarked must share some key processes with that which is benchmarking. Most companies may not be willing to share key information concerning their operations with their competitors. They are of the view that the practice would undermine their success by sharing their business secrets with other firms. In this case, although benchmarking is considered to be most effective when done on the leading firms in an industry, it can also be done in firms operating in a different industry and yet produce favourable results.

In a separate study, Amin and Amin (2003) indicate that benchmarking enables companies to become open to new ideas. Although the introduction of new ideas is in most cases often rejected because of its cost to an organisation, benchmarking helps change the attitude of both the management and employees. Through benchmarking, a firm is able to examine the processes carried out by another player, either in the same industry or from another and assess the results.

With every organisation’s goal being to be successful, every idea that would see an improvement in performance warrants adoption. The benchmarking process is also important in that firms are able to get first hand information from the best performing organisations. As such, all the stakeholders in the organisation, including the employees will be in a position to see why the implementation of the new idea is important to the organisation.

Competitiveness has the central place in economy thinking, both in developed countries and in transition countries. It is well known that small hospitality companies are the basis of development in the industry (Milohnic & Cerovic 2007). The companies are core to economic development of the countries where they are situated.

For example, they are a source of employment for the country’s population. Secondly, they are a source of foreign exchange. Tourists visiting the country are accommodated by these companies. The money spent by these foreign visitors is a source of foreign exchange which helps strengthen a countries economy and currency. Small hotels are especially emphasised in most countries. They are considered to be more flexible while compared to larger firms. As such, they are able to adapt new trends in the industries with relative ease.

The cost of the implementation of such new practices is also considerably low than that which would be incurred by large multinationals. Such firms are encouraged to be extra vigilant in the search of new ideas that would see the improvement of the quality of services being provided in the hospitality industry.

Most efforts to search for new solutions to issues affecting the hospitality industry are therefore mainly carried out in such companies. The companies however are often small and have limited experience in the provision of world class hospitality services. They therefore need to seek new ideas from leading firms in the industry which can only be done through benchmarking. The practice would furthermore increase competitiveness of this sector.

The Croatian hotel industry still has not accepted the usali standard methodology of monitoring, analysis of business and business results leadership which has been accepted worldwide (Milohnic & Cerovic 2007). Only use of the standard benchmarking indicators can ensure the right choice of managerial strategies in small hotels’ business. In this case, the benchmarking company is expected to pay a visit to another whose success in the industry is undisputed.

During the visit, they are to compare the differences that exist between their processes and that of the other company. They are also to assess the results of the other company’s processes to determine their contribution to the difference in performance between the two companies. The best practices that have been identified in the benchmarked company can be used to improve other firms in the industry.

Benchmarking does not offer real support to strategic management. If there is no comparison which takes into account the processes carried out by the organisation being benchmarked and their results on the overall performance of the firm, then the benchmarking process is in vain (Milohnic & Cerovic 2007). Failure to make the comparison would also thereafter have extremely harmful effects on the benchmarking firm as they make their own strategic decisions.

Co-dependency of business strategies and quality lies in the fact that benchmarking is a kind of investment with the purpose of increasing activity quality. Small hotels’ competitive advantage improvement could be ensured by continuous following and adaptation to the modern guest market needs. By raising the quality of the offered services, small hotels directly contribute to the rise in the ranks of a country to that of preferred tourist destination in the world.

The declarative level of quality, which is now present, should be transferred to the highest possible status in reality for the following reasons:

- To stimulate improvement of quality to ensure that guests receive more value for their money. As such, they will be more willing to hire the services of the same hotel in future (Milohnic & Cerovic 2007).

- To increase the present quality of services offered in small hotels. As such, their competitiveness will be improved a situation that increases chances for their survival in this competitive industry will be increased considerably.

- To ensure competition with the best Mediterranean destinations with the aim of creating high quality standards. Other firms will have no option but to upgrade their services in order to remain competitive.

- To integrate accommodation into the quality system. Most of the firms operating in the hospitality industry offer accommodation services to tourists, both local and international. Small companies too will be required to adopt the practice.

With respect to the case study used for this report, innovativeness is relevant to the hotel sector. Some of the advantages of benchmarking include:

- Increasing the productivity of an organisation.

- The attainment of a competitive advantage against rival organisations by adopting the best practices in the industry.

- Continuous learning initiatives are enhanced. Benchmarking is a continuous process. With the hospitality industry being dynamic, firms will need to constantly seek new information o how they can best improve the quality of the services that they offer.

- Promotes growth, in terms of profits, sales and clients by attracting a greater number of customers. Benchmarking increases on a firm’s competitiveness.

Enhanced productivity and individual design

Organisations engage in this practice for varying factors. The same are brought about due to production and individual design-related factors. According to Muschter (1997), companies that benchmark due to productivity often target the sales result of the venture. Such companies are more interested on the returns made following their investments on the changes. On the other hand, benchmarking, due to the individual design ensures organisations cultivate a spirit of quality. In this case, the firms seek to be lead in the industry in terms of the quality of services that are offered.

Benchmarking as a strategic tool

Companies today use benchmarking as a strategic tool to increase their competitive advantage in the various industries that they operate in. Benchmarking allows companies to establish the weaknesses in their competitors. As a strategic tool, benchmarking allows a company to select the best business practices in a particular industry. For instance, if a company is engaged in old practices another company will capitalise on that and adopt new techniques (Davies 2009).

The company which adopts new techniques of business leaps ahead of its competitors. A company can also use benchmarking in order to come up with strategies that outdo leaders in the market. Having benchmarked the best firms in the industry, the management of a company can look for ways to improve on the processes used therefore outcompeting the benchmarked firm.

Enhance learning

Every business entity requires new knowledge. Benchmarking creates awareness of business practices in rival organisations. Consequently, the adoption of such techniques requires education (Brookhart 1997). Continuous learning initiatives guarantee an abundance of knowledge. Such kind of knowledge is essential in ensuring organisations meet their core obligations to stakeholders who consist of the owners and the customers. The owners of the company will require high profits from its operations. Customers on the other hand expect to get value for their money by getting services that are of high quality.

Growth potential of a company

A change in a company’s culture enhances its growth. Benchmarking is seen as an important tool towards realising this. Through benchmarking, a firm is able to identify areas where it can make improvements in terms of doing things. The implementation of the new ideas that has been gathered through benchmarking is often viewed as an investment into a company. Companies tend to carry out business practices over a long duration of time.

As such, they are bound to reap benefits from the changes that have been made following a successful benchmark exercise. According to Watson (1992), benchmarking allows an organisation to seek for growth techniques from external sources through the adoption of new ideas and processes. Such a move places an organisation at a unique position of taking on future challenges. A growth potential translates into profits for an organisation.

Assessment of performance tool

Every organisation requires some form of criteria to assess its performance. Benchmarking is one of the many techniques that companies can use, to evaluate their performance. Dunn et al. (2007) are of the opinion that benchmarking is “the process that companies use in order to identify and learn the best practices especially those involving the running of operations from best firms in a particular industry” (658).

By identifying the “best” practices, companies can evaluate their processes by comparing themselves with organisations that are performing well. Based on the assessment carried out, companies detect the challenges that they face. Benchmarking provides the solutions to such challenges since it seeks to identify how successful organisations cope with the challenges that exist in the industry.

Continuous improvement tool

The potential for growth for an organisation is based on how well it can improve on its functions. Benchmarking helps companies gather ideas on how they can make improvements on their operations. Pattison (1994) used his study to point out that, benchmarking strategies help in cost reduction by up to 30%. Benchmarking establishes an ideal grading technique for matters to do with inputs and outputs and how they relate to cost. As such, the organisation implementing the ideas does not have to conduct further research.

Lyonnais (1997) is of the opinion that the benchmarking process helps in a number of key business processes. Such processes include budgeting and planning. For instance, following a benchmarking exercise, a firm will have a rough estimate of the cost that it will have to incur in the implementation of a new idea acquired from another firm. The amount of preparation required can also be predetermined based on the amount and time and effort it took the benchmarked company to implement the changes in their processes.

The use of benchmarking as a continuous improvement tool is being assessed in many companies. For instance, during the early 1980s, Ford Motor Company was faced with challenges of their rising costs of production. According to Pattison (1994), the management believed that their accounting procedures required an overhaul.

The reforms at Ford Motor Company were mainly on the company’s accounting techniques. One of the company’s lead rival in the industry at the time was Mazda. Smith points out that Mazda had an impressive accounts payable operations system. According to Pattison (1994), Ford reviewed its accounts payable operations, alongside the Mazda model, resulting in a 5% decrease on cost. Companies in the hospitality industry could also reduce their cost through benchmarking. The process promotes efficiency therefore cutting on the costs.

Disadvantages of Benchmarking

Benchmarking is one of the many business principles used in the hotel industry. A number of studies have found various disadvantages associated with the practice. The study by Ellibee and Mason (1997) evaluated benchmarking from the angle of the operations of the company. Ellibee and Mason (1997) discovered that the process is an expensive affair with respect to an organisation’s resources that include time, labour, and capital.

Employees in the company that is benchmarking another will have to be exempted from their roles during the process. The practice will have a negative effect on the performance of the company during the time. Benchmarking has also been considered to be a time-consuming exercise. It is also involving and requires allocation of a lot of resources. Capital is also required in the implementation of the ideas acquired during the benchmarking process.

In a separate study, benchmarking was evaluated based on its overall effectiveness (Learning and Teaching Unit 2012). The concept allows companies to measure the efficiency of their operational metrics. However, it has been found out that the disadvantage in this case emerges when benchmarking becomes an inadequate tool in measuring the effectiveness of the operational metrics identified (Learning and Teaching Unit 2012).

The reason behind this is that not all operational aspects can be quantified. The case also applies in the hospitality industry. Since it is associated only with the provision of services, it is difficult to determine how effective one was in the provision of one service compared to another.

Benchmarking has been evaluated based on its role in influencing the competitive advantages of organisations. The Association of Commonwealth Universities (2012a) points out that benchmarking helps to reveal the standards employed by the competitors. The shortcoming emerges in the sense that competitors can attain these standards in a way that is considered to be unethical. In the opinion of The Association of Commonwealth Universities (2012a), there is a likelihood of a competitor’s goals and visions to be flawed.

There are other instances when the said goals and visions become severely restricted. Under such circumstances, The Association of Commonwealth Universities (2012b) found that when a company benchmarks based on such standards it risks aping such flawed standards. There is also a likelihood that the company will settle for extremely low standards in an effort to increase competitiveness and to increase profitability. Efforts to cut cost may also have detrimental effects on the standards.

Cases of complacency and arrogance have also been considered to be major challenges facing firms which benchmark. In a study carried out by Yasin and Zimmerer (1995), certain organisations developed a trend where they relax once they excel against their competition, in terms of standards. Complacency emerges in cases where companies develop a mood of relaxation to adhering to certain standards.

McNair and Leibfried (1992) found that six out of the ten companies evaluated became arrogant after beating their competitors in the benchmarking process. The companies were also found to be arrogant and were overconfident in their abilities. Arrogance and complacency puts a company in jeopardy of not realising their core objectives since they overlook the need for improvement. Such companies are also likely to be outdone by other firms that are constantly improving on their operations.

Benchmarking can also be conducted in vain especially for companies that fail to apply the standards they have learnt. According to a study carried out by Bureau of Business Practice (1996), organisations that failed to come up with an action plan for change upon benchmarking fail to realise the benefits of the process.

Upon benchmarking, it is important for companies to make changes on their processes. Failure to implement the changes will translate to wastage of time, human labour, and money used to facilitate the process. Since the management is already aware of the practices that would make their organisation adopt the best practices and gain competitive advantage, failure to adopt the ideas learnt during the benchmarking process would be viewed as a deliberate choice to fail. To this end, it is advantageous to undertake benchmarking as a “stand-alone” activity.

The advantages realised as a result of benchmarking surpass its disadvantages. The Council of Australian Directors of Academic Development (2011) indicates “that organisations mostly rely on benchmarking over performance analysis tools like SWOT” (13). Benchmarking is also finding acceptance in quality assurance concepts like Total Quality Management (TQM). The reason behind these trends is that the benchmarking process helps a company gain a firsthand experience on the application of the best practices in the industry. The application of these practices and standards has already been tested and proved to be effective.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

Based on the available literature, the section looks at the business context for Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) with respect to their importance to a company. In this section, the key definitions of KPIs are provided alongside some of its characteristics

The context of key performance indicators

As already mentioned, Key Performance Indicators enable organisations to define and evaluate their progress towards attaining their goals and objectives. As such, they are in a position to identify what aspects in their firm need changing. According to the Council of Australian University Librarians (2012), evaluating the performance of an organisation is an ideal mechanism of establishing whether goals are being met or not. KPIs help a company assess their performance over a given duration of time.

KPIs enable a company to evaluate whether or not it is ‘on track’ as regards its set objectives. Wadongo et al. (2010) found that, KPIs provide organisations with the necessary strategies that help in attaining a beneficial outcome or improvement. KPIs are mainly used to assess service delivery within a particular organisation.

For example, the use of an Electronic Document and Records Management (EDRM) project is a good indication of how KPIs help organisations realise their objectives (Wadongo et al. 2010). According to Wadongo et al. (2010), the EDRM is used to measure client. Companies that use this system can influence its use in others. KPIs also play a great role in the assessment of timeliness in the delivery of service delivery.

Definitions

KPIs are characterised by a consistent thread when it comes to their definitions. They are anchored on measurable development. They focus on the progress made in the achievement of the mission of the firm. Cooper and Schindler (2011) point out that before one can define KPIs, they should first make efforts to appreciate their purpose. The following are some of the reasons that make KPIs an integral aspect of business enterprises:

- The communication of status. They highlight the position a company at the present and compare it with where it intends to be.

- To enhance overall improvement based on facts. The areas found to be lagging behind as per the evaluation are improved.

- To act as a continual status check for a business entity. Through KPIs, a company is able to constantly monitor its progress.

- To incorporate the consumer in the operations of a business. It is every business’s goal to provide the highest quality of services in the industry for consumers. Attainment of the goals will therefore translate provision of better quality services.

A definition of the term KPI could have been given from the outset. However, Cooper and Schindler (2011) point out that there are a number of variations of the definition of a KPI available in the literature written on this topic. The same makes it difficult to define on a rudimentary level. Cooper and Schindler (2011) argue that an ideal definition of KPIs draws its understanding from the operational approach. With such an approach, more practical tools are required as opposed to discursive ones.

Key performance indicators have a lot to do with the assessment of an organisation. To this end, Abrahamson et al. (1993) defined KPIs as follows:

“A particular value or characteristic used to measure output or outcome. KPIs are also used as measures of service quality, performance efficiency, and customer satisfaction. Quantitative performance indicators may include volume of backlogs, processing time, reference response time, ILL delivery time, FTE to user ration, availability of information needed, etc. Qualitative performance indicators include user perception of service quality, user satisfaction with reference response, types or levels of service available” (4).

Process of Benchmarking

The process of benchmarking is carried out over a series of five main phases. In a study by Bhutta and Huq (1999), a number of companies, both in Europe and the United States of America have employed the process to carry out their benchmarking activities. According to Bhutta and Huq (1999), it is best when the process is conducted in a sequential manner. The practice helps ensure consistency. Adhering to the sequence also ensure no aspects of benchmarking are left unaddressed through the process. The same was found to enhance continual improvements of as organisation’s core objectives with respect to the set out standards. Table 1 is an overview of the benchmarking process

Stage 1

The first stage has to do with planning. According to Bhutta and Huq (1999), the first phase is the preliminary one. Here, companies identify what elements require to be benchmarking. To this end, most of the companies evaluated, have commenced this phase by evaluating the business plans. Planning calls for thorough preparation. To this end, such aspects like the methodology to be used and the necessary participants play an important role in this stage. Preparedness of the organisation for the process will ensure its success.

Data collection

The stage involves deciding on the aspects to be measured. Also, this stage outlines how the measurement will be carried out. Wober (2001) argues that a definition of the benchmarking envelope becomes necessary in this stage. The benchmarking envelope allows an organisation to establish the metrics that will be used for the process. The metrics must be clearly defined. Bureau of Business Practice (1996) argues that the same allows comparability of the datasets to be collected. In this stage, the appropriate data collection technique must be outlined.

Data analysis

Data analysis entails the validation and normalisation of the information collected in stage 2. Bureau of Business Practice (1996) suggests that all data requires validation prior to any analysis. The same helps to establish the accuracy and completeness of the information collected. Data normalisation makes it possible for bench markers to compare the operations of different organisations. Omachonu and Ross (1994) argue that the absence of data normalisation makes direct comparisons of an impossible undertaking. Data analysis is meant to outline the pros and cons of the entire benchmarking initiative. Ultimately, the analysis will help provide recommendations for the focus of performance improvement efforts.

Reporting

The analysis should be reported in a manner that can be easily understood. Omachonu and Ross (1994) add that the reporting must be done through an appropriate medium that can be accessed by the necessary stakeholders. The study by Hacker and Kleiner (2000) found that many benchmarking exercises are terminated at this stage. Hacker and Kleiner (2000) argue that companies can maximise the value of benchmarking by taking the exercise further. In this regard, the benchmarking process can extend to a stage where companies adopt the best policies from other companies.

Types of Benchmarking

The benchmarking process is one that is characterised by a number of features. According to Houston (2008), the need for efficiency in an organisation calls for diversity in the key performance indicators. The resultant effect of this diversity is the existence of several types of benchmarking. Elmuti and Kathawala (1997) are of the opinion that there exist four major types of benchmarking. They include the following:

- Competitive benchmarking.

- Process/generic benchmarking.

- Functional/industry benchmarking.

- Internal benchmarking.

Internal benchmarking

Internal benchmarking is the kind that is done against the operations of a given organisation. The study by Elmuti and Kathawala (1997) observed that most organisations have almost similar functions within their internal operating mechanisms. To this end, the internal benchmarking happens to be the most commonly used type owing to its simplicity. The concept of internal benchmarking evaluates an organisation with respect to the internal performance indicators. Internal benchmarking ensures that a company can share multiple forms of information with its customers.

Benchmarking enhances immediate gain. Edith Cowan University (2007) suggests that the benefit of immediate gain to an organisation is realised through the identification of the most effective internal procedures. However, the study by Oliver (2011) made a strong case that there exists a great relation between the use of internal procedures and realising immediate gain. According to Oliver et al. (2011), immediate gain are realised through the transfer of the internal procedures within an organisation. A similar research was carried out by Matters and Evans (1997). It was found that organisations that use this type of benchmarking retain an introverted perspective of their operations.

Competitive benchmarking

Competition, in business, allows companies to interact as they seek to woo the clients in the market. According to Finch and Luebbe (1995), this type of benchmarking is carried out externally. The objective of competitive benchmarking is to come up with a comparison between the performance of companies in a given market segment. Such companies mostly deal with the same kinds of commodities. With respect to the current report, comparative benchmarking would be carried out between hotel intercontinental and the Marriot hotel.

The benefit of this type of benchmarking is realised when a company can determine their performance in a given market. Usually, a company that perceives itself as poor performing benchmarks one of the leaders in the industry. By adopting the best practices used in a successful company, a firm is assured of better performance which is vital in the outdoing competitors.

The main disadvantage associated with competitive benchmarking however is that competitors have the tendency of withhold information from one another. Elmuti and Kathawala (1997) suggest that when direct competitors need to get information from each other, and the same is not forthcoming, it becomes difficult to evaluate their performance. An example would be when a company withholds certain information from their financial reports.

Such a move makes it difficult for other competing organisations to gauge performance due to the missing variables. Companies are also often afraid that letting competitors in on their secrets will undermine their ability to maintain competitive advantage against them. As such, they may result to giving misleading or incorrect information to competitors.

Functional/industry benchmarking

Industry benchmarking is carried out externally in relation to a given organisation. According to Finch and Luebbe (1995), organisations using this type of benchmarking carry it out against market leaders in a given industry. In this type of benchmarking, companies evaluate the best functional operations in the leading organisations within a particular industry. In cases where benchmarking partners are involved, the two must have similar characteristics in relation to their market (Matters & Evans 1997).

In most cases, the similarities are based on technological aspects. The benchmarking company can decide to implement the functional operations in the leading organisation as they are or make improvements. The form of benchmarking is conducted by ambitious firms seeking to be one of the best performing in the industry by outdoing the existing leaders.

Process/generic benchmarking

As already discussed, benchmarking is carried out with respect to the best operational processes in a given organisation. Generic benchmarking places emphasis on the business practices of a company that includes its procedures and functions. Finch and Luebbe (1995) suggest that generic benchmarking is used across dissimilar organisations but is difficult to implement. The reason behind this is that it is difficult to compare processes and their outcomes for two firms that are not operating within the same industry.

The use of generic benchmarking requires that the stakeholders in the organisation have a clear understand on the working of the process being benchmarked. Based on this kind of benchmarking, one is required to pay attention to the procedures used (Finch & Luebbe 1995; Matters & Evans 1997). Respective companies are required to evaluate their performance based on a comparison with the processes of benchmarked firm. The same is followed by a clearly outlined framework on how they wish to use the benchmarking process to improve their practices.

The Legal Aspects of Benchmarking

Benchmarking is a practice with generalised procedures. According to Watson and Weaver (2003), the level of legal exposure among benchmarking firms varies with the industry in which they operate, the type of benchmarking they have engaged in, and the business type that they are in” (Bureau of Business Practice 1996, 152). The legal aspects of benchmarking include six critical areas of expectation. In point form they include the following:

- The proprietary information.

- Can the idea be treated as intellectual property

- can a firm be said to have engaged in unfair trade practices

- Is there evidence of benchmarking process having occurred between the two organisations?

- Disparagement.

- Trade libel.

Legal issues, surrounding benchmarking, are essential in cases where two companies having engaged in the process fail to reach an agreement. An example is witnessed when the recipient, of benchmarking data, leaks the same to a sister company. Carroll and Buchholtz (2003) carried out a study to evaluate the legal framework in benchmarking. According to Carroll and Buchholtz (2003), most violations occur in the public domain. The benchmarking company receives valuable information that when leaked would have serious implications on the competitiveness of the benchmarked firm. Organisations are forced to reconsider the sharing of information out of the fear of the disputes that might result from violations.

Companies can decide to develop certain techniques but fail to publish. Such a company lacks the documentation to show that indeed it own the ideas behind the technique. Such confidential information is considered proprietary. As a regulator the Securities and Exchange Commission came up with a regulatory framework that can be used to deal with such information (Epper 1999). The framework includes guidelines that outline how to request and accept such information.

Epper (1999) argues that when companies share information, they should do so openly unless it is considered to be proprietary. Such information must be shared with consent, otherwise it will be considered as a violation. Even with benchmarking, the ideas are not to be implemented without the consent of their owner.

Intellectual property is a legal aspect that should be given special attention to when benchmarking. According to Omachonu and Ross (1994), intellectual property is the creation of an individual. Intellectual property demands that the developers have a patent or copyright the product to prevent the duplication of their ideas by others Omachonu and Ross (1994). Intellectual property is a concept with several guidelines. For instance, organisations are encouraged to understand the nature of the property in reference. In most cases such a scenario arises due to joint ownerships.

In most cases, this issue arises when the benchmarking company buys patent rights. The terms of the agreement must be clear to avoid ambiguity. The two companies may decide to share the idea as joint owners. In other cases, a company can buy patents fully, therefore prohibiting their use by others. Disputes arising from such matters lead to the role of an intellectual property attorney being questioned.

Benchmarking is often characterised by several instances of unfair trade practices. Fortunately, the enforcement of a legal framework, on this front, lies with the government. Bryman and Bell (2007) use their study to go down the history lane where the law was not seen to support deliberately co-operative engagements.

However, in the past legal frameworks were tailored in such a way that they would examine all transactions between the two companies very carefully to determine if there are any irregularities that can be detected. Legal officers would scrutinise their engagements to find out whether there are any ulterior motives by the violating company.

The risk of companies falling prey to others, in the name of benchmarking, has increased awareness of unfair trade practices in the industry. Companies today have become extra vigilant in the determination of how much information the benchmarking firms can access and to what extent they can utilise the information gathered. As a result, complex contracts are being drafted today to ensure that both parties are aware of their obligations in the practice.

The practice does not imply that benchmarking is against competition (Bryman & Bell 2007). What this means is that, the lines could become blurred when it comes to interacting with competitors and alertness is welcome to avoid unfair practices. The efforts to avoid these violations have lead to increased distrust among companies. As a result, they tend to withhold valuable information especially that related to their financial reports. The move undermines the very reason for conducting the benchmarking process which is information sharing.

Weaver (2001) illustrates three standards to apply under such circumstances. In the first instance, business partners are required to foster a tone of goodwill in their dealings. Weaver (2001) argues in favour of setting a tone since it allows companies to compete with each other without restraining trade. As such, the industry is likely to grow rapidly as firms engage in healthy competition to be the leading companies in that particular industry.

Goodwill also promotes trust between companies which allows free sharing of information. Secondly, the competitors are encouraged to engage with forthrightness on general operational procedures. Being direct and clear during the benchmarking process is essential since it helps avoid the provision of misleading information. Finally, organisations are encouraged to use a less risky means of obtaining information.

The means of data collection used should ensure that the minimal disputes would be likely to arise. Such data sources include other firms that have benchmarked in the past, library facilities, and the Internet. Today, most leading companies in an industry post information on the services and goods that they offer, as well as their best practices in public platforms, such as the internet. It would be less risky to gather the necessary data from such sources without necessarily having to engage in benchmarking.

Evidence is an integral aspect of the legal framework associated with benchmarking, notwithstanding its simplicity. Evidence deals with proof of information exchange among organisations involved in benchmarking. Such kind of information outlines the failures and successes of the organisations involved. Watson and Weaver (2003) suggest that evidence is essential to safeguard against complaints about corporate espionage. However, the same is done without legal ramifications.

Benchmarking Trends in the Hospitality Industry

The hospitality industry has a number of trends with benchmarking. According to Furunes and Mykletun (2005), conference tourism is turning out to be a big hit with hotels. To this end, meetings and accommodation are seen as the two main trends of benchmarking in the hotel industry.

With respect to meeting, Furunes and Mykletun (2005) talk of lightening speeds of internet connectivity. Hospitality is not hospitable when the internet connectivity is slow. Hotels are increasingly benchmarking their connectivity bandwidth with the best in the industry to ensure that they attract as many customers as possible, as well as to remain competitive within the industry.

Content is also one of the many emerging issues in benchmarking across the hospitality industry. Bureau of Business Practice (1996) observed that conference tourism thrives on web content. Hotels are required to generate sufficient content to ensure that they attract more clients to their side. When a hotel is visible, and connected, courtesy of a website, the same translates into good business for the organisation. Most of the businesses in the industry today own websites, blogs, and are active in their social media pages.

Communication and the involvement of the consumers have become vital. As such, the companies are able to sensitise the potential consumers in the market of the services offered and why they are the best in the industry. Organisations that are not able to meet this trend are forced to develop the same elsewhere. The same necessitates benchmarking.

Environmental protection is an emerging point of interest in various organisations. Companies are increasingly developing the awareness of environmental protection and its importance. Organisations that fail to adhere to the standards of environmental protection face the risk of being branded as environmental unfriendly.

With increases awareness among consumers about the negative effects that are associated with environmental pollution, the negative popularity is likely to reduce on the competitiveness of a firm. Carroll (1979) points out the need for hotels to adopt practices that are conscious of the environment. Min and Chung (2002) carried out an empirical study on benchmarking. The study sought to suggest that dynamic benchmarking is the best improvement tool within the hospitality industry. The study made use of the following dimensions:

- guest room values

- front office service attributes

The dimensions mentioned above are essential in discovering the “best practice” within the South Korean Hospitality industry. Based on the study, some of the trends of benchmarking within the industry include the following:

- Cleanliness of a guest room.

- Courtesy from the staff in a hotel.

- Tranquillity in the accommodation quarters.

- Efficient response to complaints.

- The overall comfort of the bed.

The never ending competitive nature of the hotel industry, calls for hotels to continuously improve service standards. To this end, dynamic benchmarking becomes necessary since it guarantees service excellence. Nassar (2012) carried out a study to evaluate benchmarking in Egypt. The study revealed an important aspect of benchmarking that is getting increased attention. The cost of benchmarking is gradually eating into the operational costs. To this end, emergent trends regarding the same are to share the costs. Hotels that find mutual points of interests can share the costs of benchmarking, thereby reducing on the overall cost.

Benchmarking Guidelines

One major aspect of benchmarking involves the preparation of an annual report. According to Oliver et al. (2011), an annual report provides necessary information pertaining to the performance of a company. Such information includes the necessary benchmarking practices. Benchmarking should also contain information pertaining to costs. The procedure of benchmarking is a financially engaging endeavour. To this end, an illustration of the cost makes the accounting process easier.

Benchmarking should protect the privacy of the second company. According to Magd (2008), the process of benchmarking exposes an organisation to classified information about another. Disclosure of such information will be considered a violation of trust. The same results into a conflict. As a result, benchmarking is considered to be a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ where the two parties build trust by honouring their origin commitments to the bench marking process

The following schedule is a sample of some of the guidelines required of a benchmarking process:

The schedule illustrates the benchmarking guidelines for organisations practicing the same in Colorado. The main areas of interest include the assessment and reporting. Cost is one of the considerations that great attention should be paid to when benchmarking. To this end, budgeting and the maintenance of the financial information are recommended. The Ergonomics program, as outlined in the schedule, is one such regulation that calls for a budget.

Results

Overview of the Intercontinental Hotel Group

The International Hotel Group (IHG) is a multinational chain of hotels incorporated in Britain. The company has its headquarters in Denham, UK. The company traces its history as early as 1777, where one William Bass set up a brewery at a place called Burton-on-Trent. Over the years, the brewery thrived, giving rise to other breweries.

The brewing company ultimately led to the growth of the industry. Over a century later, William Bass ventured into the hotel industry by acquiring the Holiday Inns International. In the early nineties William Bass launched the Crowne Plaza hotel. To this date, IHG is a key player in the global hotel industry boasting of 9 preferred brands. Today, IHG has a total of over 4600 hotels under it. The hotels are in over 100 countries.

The Intercontinental Hotel Group has, over the past decade, maintained a record of sterling performance. The same is accredited to the company’s strategy. In 2012, IHG made a promise to refund a total of USD1 billion to its shareholders. According to Magd (2008), the payments would be made as dividends and stock each at $ 500 million.

The Intercontinental Hotels Group consists of three main parts namely the midscale, upscale, and luxury. The organisation’s main business model is the franchising of their brand. According to Bureau of Business Practice (1996), franchising allows a company to expand at a rapid rate with limited operating capital. The franchising of their brand is considered an asset-light approach to business. The benefits of such a strategy include a reduced cost on income volatility. The business model, adopted by IHG has proved to have a high return on investment. Consequently, the company has witnessed tremendous growth in the sector.

The operating strategy, at IHG, is based on its portfolio of a talented workforce, brand preference, and its exquisite class delivery system. The franchise has a total of 3555 hotels spread out across the world. Recently, the company has increased its interest in America given 670 developments lined up. To this end, benchmarking has become a necessary tool for sustaining it plans to grow. The Intercontinental Hotel Group is a brand that is identified easily across the globe. Consequently, a humanitarian approach would see its performance rise. Benchmarking was carried out with respect to corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Corporate Social Responsibility

Each and every organisation or company is required to act in a responsible manner in the society where it is situated. According to Birch and Moon (2004), CSR initiatives help boost a particular brand. Corporate social responsibility is a diverse field, ranging from the environment to individual causes in the society. The objective of CSR is to give an organisation a human nature. CSR initiatives give the impression that a company is not all about making profits.

As such, CSR can be used as an effective marketing tool for the organisation brands (Campbell 2006). The Intercontinental Hotel Group has participated in a number of CSR initiatives in the past. However, to ensure they are the best, the same was benchmarked against other players in the industry. Specifically, the benchmarking was carried out based on CSR at Hotel Rezidor. The two main benchmarking practices included the environmental performance and labour management.

Environmental performance

Waste production is a serious concern among all the member hotels in the IHG chain. As part of their CSR strategy, they must cut on the amount of waste produced. According to Carroll (1991), satisfactory waste production must be set at between 40 grams and 1000 grams per guest for every night they are accommodated, based on this benchmark level the IHG appears to be falling short of expectation on their European outlets. Some IHG establishments in Europe recorded wastes levels as high as 1200 grams per guest.

Considering the expansive nature of the Intercontinental Hotel Group, the specific figures on waste production were not easy to obtain. The difficulties are an illustration of the complex nature of having a uniform waste disposal and measurement practice (Joyner & Payne 2002). The highest figures of waste disposal were obtained in the United Kingdom.

Waste disposal is directly associated with water consumption. According to a survey carried out by Bloxham (2009), there is a varying rate of water consumption in Europe and America. The figures placed Europe at a higher consumption rate compared to America. Bloxham (2009) argues that the high consumption rates are not necessarily a reflection of human water consumption. Most of the water is used in some hotels for geothermal power.

In the polar region, hotels do not use fossil fuels for energy to avoid interfering with the climatic conditions of the area. Most of these areas are tourist attraction sites as a result of their snow cover. They also host different sports, such as ice skating. The same acts as a corporate social responsibility to the environment since the company’s decision to avoid using fossil fuels helps avoid global warming which would lead to a change in the polar climates. Water consumption is also high in drier regions and the justification is provided by the demand (Kuran 2004).

The IHG decided to benchmark its CSR, on environmental policy, based on the best practices in the industry (Kimber & Lipton 2005). Consequently, the five step procedure discussed in the literature review was applied in this case. According to Burton, Farh, and Hegarty (2000), benchmarking practices are required to get the approval of all the stakeholders associated with the organisation (Orlitzky, Schmidt & Rynes 2003). To this end, most of the IHG franchises in Europe carried out surveys to determine the appropriate waste management techniques for the organisation.

Waste from hotels is mostly biodegradable. To this end, most of the participants suggested that IHG should adopt a waste management policy. According to Carlisle and Faulkner (2004), organisations that take initiative on environmental protection appeal to the market in a positive way (Muller 2006). As such, IHG began their benchmarking process using the survey to ensure that the responses are an accurate representation of its market base.

The survey also sought for opinions as to the best waste management technique currently being used in the hospitality industry (Maignan & Ferrell 2000). According to Maignan and Ralston (2002), the installation of recycling units in hotels is an emerging trend (Waddock & Graves 1997). The practice guarantees that about 95% of the waste generated and recycled can be re-used in the establishment.

The second phase of the benchmarking process involves the collection of data. Parnell and Hatem (1999) argue that the information relating to the recycling of waste is obtained from universities and databases associated with environmental protection. To this end, the data collected touched on practices that include recycling hotel waste to energy. Also, the recycled water can be used for other purposes like irrigation and showering (Smith 2000). In the long run, the waste recycling procedures are an attempt at IHG to create an environmental policy of CSR.

Energy consumption in hotels is also an area of concern, considering the high dependence of electricity in the provision of services (Schlegelmilch & Robertson 1995). To this end, IHG can increase their water consumption on the basis of geothermal energy. A comparison among some of the IHG establishments in Europe points to a similarity in the amount of energy required compared to water usage (Smith 2000).

Twenty-one of the thirty participating hotels from Rezidor Hotel Group provided figures on energy use. The pattern of energy use at Rezidor hotels is similar to that of water consumption. Hotels in Scandinavia and the UK are within, below the benchmark range for satisfactory performance with the exception of one hotel in the UK, one in Norway and one in Sweden (Szilagyi & Batten 2004).

As with water consumption, one of the two hotels in the United Arab Emirate presents the highest level of energy use, more than double the benchmark level. The hotel in Saudi Arabia reported the lowest level of energy use after Iceland, while Bahrain exceeds benchmark levels for satisfactory performance (Vitell & Paolillo 2004). Energy use at the hotel in China is below the benchmark level.

Labour management

Labour is an integral resource with respect to the operational affairs of an organisation. According to Ibrahim and Parsa (2005), corporate social responsibility has overlooked the role played by a company’s workforce. The practice makes it difficult to associate labour management with corporate social responsibility.

In a study to examine CSR across cultures, Langlois and Schlegelmilch (1990) argue that in many societies, including the marginalised, are gradually accepting the notion of promoting gender equality (Hofstede 1980). In the IHG, the workforce is mostly skewed in favour of the men. However, based on several studies, the company has started engaging the services of women in areas that are considered hostile (Hofstede 1981). The figures for gender equality in the company are as follows:

- Europe: Male (50%) Female (50%).

- Asia: Male (43%) Female (57%).

- Middle East and Africa: Male (65%) Female (35%).

The figures are a reflection of the management employment criteria, at IHG, with respect to gender. The company has a responsibility to ensure that every group in the society is considered Gender considerations are of most importance (Warner 1991). With respect to other hotels in Europe, Langlois and Schlegelmilch (1990) state as follows:

“Every hotel in Scandinavia has at least 50% women in white-collar positions. The figure of 100% reported by a hotel in Iceland was explained by the fact that there are only two white-collar positions at the hotel, and both were filled by females. The hotel in China reported that 74% of its white-collar positions were filled by women. Hotels in Sweden were as a group closest to the benchmark figure of 65%” (Langlois & Schlegelmilch 1990, 35).

The figures are representative of how the Rezidor Hotel group, employs personnel on the basis of gender (Story & Price 2006). IHG, in a bid to improve its appeal towards both genders, started a similar campaign to employ mid and top level management on an equal gender basis. However, Magd (2008) cautions against overstretching the gender issue.

Failure to carefully consider such decisions will lead to the employment of unqualified individuals for the purpose of fulfilling the benchmarks that have already been established by the Rezidor Hotel Group that advocate for equality in the employment of both genders especially in the ‘white collar’ job positions. The argument stems from the fact that the hospitality industry has a stereotype for the female workforce. To this end, rationalisation measures should take into account a people’s cultures. Langlois and Schlegelmilch (1990) suggest that IHG can apply the gender card at the top management level. Such a move sends a stronger message to the market.

Another area of interest in labour management includes the aspect of training. Magd (2008) argues that hotels can assess their performance in this area based on the percentage of the total cost on labour. Unfortunately, the sensitivity of the information resulted in nondisclosure from IHG. However, the Rezidor Hotel Group compares to IHG and their information helped provide an estimate. According to Langlois and Schlegelmilch (1990),

“The difficulties in providing such figures appear to stem out of differences in measurement units. Some hotels reported number of training hours per employee and some reported the total cost of training per year, while others simply indicated that they do not have accurate figures available” (527).

In the study, the information by the managers, on the training budget, was not consistent. Whereas one group suggested that 1% was for training, another group insisted that the same figure was used as wages for the workforce. As already mentioned, the Reziton Hotel Group does not have a huge disparity with IHG. Their operations are almost similar. To this end, most hotels are found not to honor the training requirements.

Separately, Langlois and Schlegelmilch (1990) carried out a study to examine labor management issues in China, Bahrain and Sweden. Hotels in these regions provide the information without batting an eyelid. Langlois and Schlegelmilch (1990) make the following observation:

“Hotels in China, Bahrain and Sweden provided the most detailed information regarding expenditure on training with figures for several years, whereas hotels in the UK at best provided a rough estimate. The hotel in Egypt presented the highest expenditure on training as a percentage of total labour costs, which might be explained by the fact that the hotel has only been open a year, and that the first year of operation requires a greater amount of training” (536).

Based on the figures presented above, it is possible for IHG to base their labour expenses against peers in the industry. Benchmarking on the labour management is an avenue through which an organisation caters for the interests of their workforce. With a satisfied workforce, IHG is likely to record considerable growth in the coming years. The reason behind this is that the processes within the organisation are to be guided by these employees. Their satisfaction is therefore vital in ensuring the smooth running of the organisation. Watson and Weaver (2003) suggest that organisations which benchmark along similar lines are guaranteed to improve their brand visibility.

Key Performance Indicators

In the hotel industry, the determinant for performance is based on a number of indicators. With respect to the benchmarking at IHG, there are two KPIs which were evaluated. The KPIs that were used were accommodation and the cost of labour.

Accommodation

Room rates in hotels are not static. According to Ross (1995) the market and location play an integral part in determining the price of accommodation in a hotel. Hotels brands that are located within commercial cities with a high population density are likely to charge higher since their products and services are in high demand. Brands located near to tourist attractions sites, major transportation facilities, such as air ports, railway stations and bus terminals are also likely to charge higher than those that are located in remote areas.

With a high number of rooms being sold within a specific amount of time, it is evident that there is a high demand for the services. As such, room rates are likely to go up. Low numbers of rooms sold have inverse effects on the room rates. However, rooms are only sold if the brand of the hotel appeals to the market segment that the organisation seeks to target. Ross (1995) argues that that CSR helps to build a brand. At IHG, the CSR initiatives catered for have resulted in an increase in clients notwithstanding the high rates.

Labour costs

Labour costs have a direct implication on the morale of the employees. Based on the CSR initiatives, IHG incorporated training costs on their labour budget. According to Bureau of Business Practice (1996), the training of employees his part of the CSR initiatives advanced. However, the move increases the cost of labour provided by the employees to the firm.

At IHG the labour costs went up. Since the remuneration rates of the employees are likely to go up after training, they feel more valued by the organisation. Although the cost of operations is likely to go up, the productivity of the employees is also bound to increase drastically. As a result, the return on investment is realised with increased numbers of visitors to the hotel chain.

Overview of the Marriott Hotel

The Marriott Hotel is a chain of hotels that traces its history to the 1950s. According to Veleva and Ellenbecker (2000), the Marriott chain of hotels started out as a motel in Washington D.C. Upon growth, the company increased the number of motels to two before the company ventured into the resort hotel business in 1967. The Camelback Inn was opened in the state of Arizona. International expansion saw the company venture into the South American Market in 1969 with the opening of Marriott in the city of Acapulco in Mexico. The Marriott Hotel in Amsterdam opened in 1975, signalling entry into the European market.

Benchmarking practices at the Marriott Hotel

The Marriott Hotel Surfers Paradise Resort carried out benchmarking on its accommodation. The Hotel comprises of a 35–storey hotel with a total of 403 rooms. The Marriott Hotel Surfers Paradise Resort has a floor area of 46 920 square meters. The Hotel’s main area of interest is the energy management. Consumption was also a key area of concern. To this end, benchmarking was carried out in this regard.

According to Peter Knuth, who is the Chief Engineer,

“An incremental and strategic approach has paid off. Over the past 10 years, we have significantly reduced energy costs by routinely incorporating energy efficiency and energy management into our maintenance budgets and reporting systems. We have deliberately fostered a culture of efficiency. Recently we identified a leak in the hotel’s potable hot water pipe work through our daily monitoring of hot water, gas and electricity demand. The water reading indicated higher (…) prompted me to investigate. I organised for repairs to be completed within a few hours. Previously, this sort of issue could have gone unnoticed for months” (Wartick & Cochran 1985, 759).

Energy and water concerns are the main areas of interest when it comes to issues relating to the hotel industry the information outlined by the engineer illustrates the company’s policy on matters relating on energy. To this end, there organisation adopted an approach aimed at tapping into renewable energy sources. As such, the cost of energy in the organisation is likely to go down. The development allowed the company to also reduce on its total operational cost. With the use of renewable energy sources, the company will also reduce on the amount of waste generated. Renewal of energy in most cases depends on the utilisation of waste. Some of these practices are carried out in various jurisdictions, particularly in Europe. Incorporating the same at Marriott would greatly improve the performance of the organisation, overall

Key performance indicators

The benchmarking aimed at promoting the performance of an organisation. In the case of Marriott Hotel, the benchmarking was targeted at placing the company on the same level as companies that are energy friendly. According to Welford (2005), energy efficiency is an emerging concern in all industries in the world economy. The same has an impact on the cost of doing business and the return on investment. To this end, the performance indicators include:

- Rise in the number of clients: as already mentioned, the use of alternative energy triggers an upsurge in the number of clients. According to Welford (2005), the same is brought about by the presence of unlimited energy. In the hotel industry such a move translates into unlimited fun by the guests. Separately, the hotels will attract considerable numbers of environmental activist. The same add onto the increased revenue.

- Reduction in the costs incurred in the normal running of operations. The costs incurred in terms of energy are often high. However, the use of other energy sources like solar helps to mitigate the recurrent expenditure. To this end, Welford (2005) points out that a hotel chain that makes use of renewable energy sources will begin to see a decline in its operating costs. The same is true for the Marriott Hotel

Comparison between Marriott and IHG

The benchmarking at IHG was carried out based on the performance of another company. However, the Marriott Hotel carried out benchmarking based on the industry demands. According to Preston and O’Bannon (1997), benchmarking can be based on the industry or against a competitor. Such a disparity is all about the different types of benchmarking that exist. In both cases, benchmarking involved the aspect of the environment.

Wood (1991) insists that the hotel industry requires coming up with clean energy solutions. The practice helps in the promotion of CSR especially in matters of caring for the environment. The key performance indicators in both cases were different. However, it is important to appreciate that in both cases, the KPIs illustrated growth.

As illustrated in the literature review, the hotel industry is bound by certain rules and regulations when it comes to benchmarking. In this regard, the IHG and Marriott carried out their benchmarking without paying attention to the laid down procedures. Notwithstanding the success of the practices, companies are advised to adhere to the laid down rules and regulations.

Discussion, Recommendations, and Conclusion

Discussion

Most of the data used in this study was from secondary sources. The primary objective of the study was to identify benchmarking practices in the Hospitality Industry. Quazi (2003) argues that before the implementation of benchmarking practices in the hospitality industry, stakeholders are called upon to make sure they understand the concept. To this end, Benchmarking was found to be a continuous and systematic process of evaluating specific parameters of a company and its performance.

With the constantly changing trends in the hospitality industry, the players need to constantly benchmark in order to adopt the best practices in the industry. From the literature review benchmarking parameters include the products and services. The two are often coupled with the processes and outcomes in a given company. Benchmarking is all about how the evaluation of the said parameter is carried out in comparison to those in other organisations.

The process of benchmarking has been used to realise certain outcomes depending on the company in reference. To this end, the process of benchmarking depends on the industry where a company is domiciled (Carr 1968).

Trends that highlight the state of KPIs in Lithuania’s hotel industry

The Occupancy rate of the industry’s hotel businesses

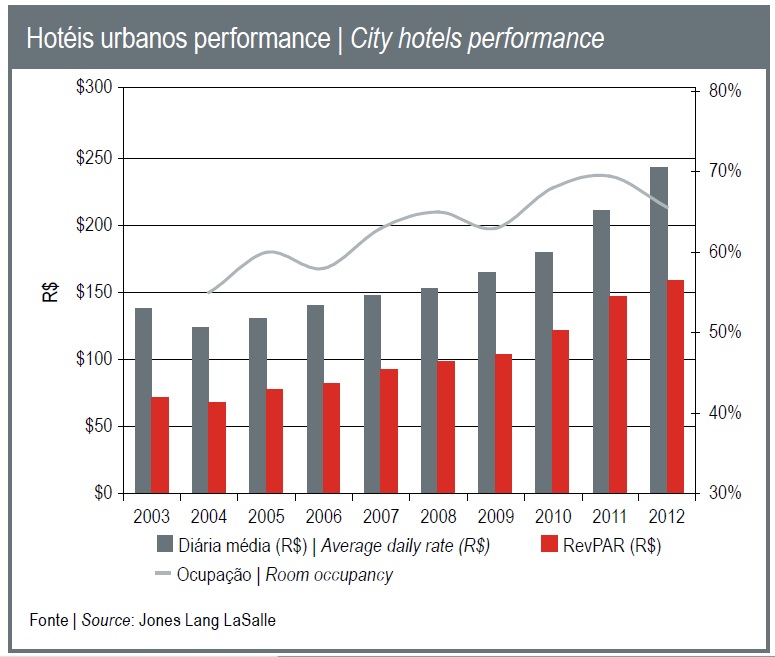

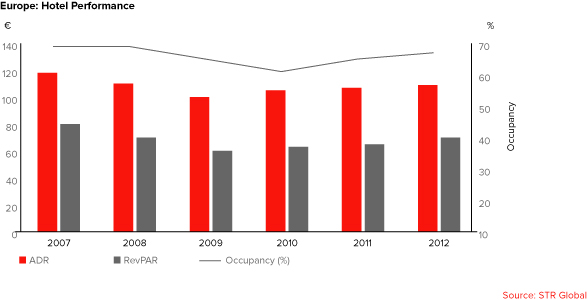

Graph 1 clearly shows the state of instability in the industry. Occupancy rate in the hotels operating in the economy often gets to highs of up to an average of 70% during summer season, which spans between the months of June and September. Based on the interpretation of the graph, hotels operating in the industry in 2011 recorded an increase in occupancy rate of about 6 points on average in every month while compared to the preceding year. However, the was a similarity noted between the 2011 and 2012 with slight increases in terms of occupancy rate being realise d between January and July 2012.