Abstract

The past two decades have placed much emphasis on sustainability practices within different industries. In 2017, half of the top 100 fashion brands implemented a sustainable approach in their practices. The growth of the fashion industry is dependent on the social, economic, and environmental aspects of sustainability. In this view, the emphasis on sustainability from the perspective of consumers has been a mainstream issue globally. However, a significant concern is that companies provide false information in advertising their products, making customers develop skepticism about their greenness.

Therefore, this study investigated how skepticism towards Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices influences both intentions of consumer purchase and negative Word Of Mouth (WOM) among consumers of Adidas and Nike. By employing one-way ANOVA and multiple regression, this study analyzed data collected from the young consumers (between 18-35 years-old) of Adidas and Nike who reside in The Netherlands. The results indicated that consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices of CSR motives and green products have a negative influence on green purchase intention, but a positive effect on negative WOM intention.

Moreover, results showed that corporate reputation has a negative influence on CSR practices of Adidas and Nike. Therefore, this study concludes that fashion companies need to be trustworthy in their CSR practices to decrease the level of consumers’ skepticism, diminish negative WOM, and augment the green purchase intention. Based on its findings, the study recommends fashion companies to improve their corporate reputation, the credibility of CSR practices, and creating awareness about the importance of sustainable sneakers among consumers.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge everyone who played a role in the process of my master thesis. First, Special thanks should be given to Ms. Kviatek for her kind approach, flexibility and efforts in providing me with the best knowledge and relevant information regarding this topic. Second, I would like also to give a special thanks to my parents, my uncle Mohemmed and my x-wife who have encouraged me to start this program in the first place. Additionally, I would like to acknowledge my friend Shaker for his support which made it possible for me to accomplish this degree. Finally, special thanks should be given also to Ms. Ding and Ms. Xiaoyan for providing valuable information and answers regarding the questionnaire and the data analysis through the Discussion Forum. From friends and family to the supervisor and from other guiders to all participants in this study, thank you all.

Introduction

Study background

In the past two decades, business sustainability has garnered much attention from both academicians and practitioners across different industries all over the world (Turker & Altuntas, 2014). While the topic has gained much controversy, most businesses consider sustainability essential for their practices. Recently, sustainability has had an increasing potential value. Therefore, through focusing on sustainable development, firms can improve their market share, create value, and gain competitive advantage among other firms (Govindan, Khodaverdi, & Jafarian, 2013).

The three dimensions of sustainability, referred to as the Triple-Bottom-Line, focus on addressing social, economic, and environmental issues (Govindan et al., 2013; Choi & Ng, 2011; Benn, Dunphy, & Griffiths, 2014). To improve the sustainability of businesses, firms must formulate CSR strategies by creating policies that integrate environmental, social, and ethical rights into business operations (Tennant, 2015).

The importance of sustainability is rising in several industries, including the fashion industry. This industry accounts for 6% of the world export of manufactured goods (World Trade Organization, 2018), and it has been rapidly growing with a wide range of products that accommodate people’s wants and needs from clothing accessories to footwear. According to the annual research report, the global footwear industry reached $246.07 billion in 2017, where it is expected to reach the global market of US $320.44 billion in 2021 (Marques, Leal, Marques, & Cardoso, 2016).

Companies in the footwear industry face a considerable level of competition. Additionally, there is an increasing demand for sustainability in the supply chain. Hence, the sustainability requirements regarding environmental and social aspects for manufacturers are becoming stricter with time (Chopra & Meindl, 2016).

A company’s relationship with environmental issues determines its reputation (Caplan, 2003). CSR is a significant predictor of affective commitment among employees and causes a positive influence on corporate reputation (Ditlev-Simonsen, 2015). Due to the association, more fashion companies consider the aspect of sustainability in their planning (Choi & Cheng, 2015; Agag & El-Masry, 2016). Adidas and Nike, for example, have stepped up strategies for their sustainability. Adidas has created a greener supply chain and targeted specific activities, such as the elimination of plastic bags and participation in different sustainable projects (Adidas, 2019).

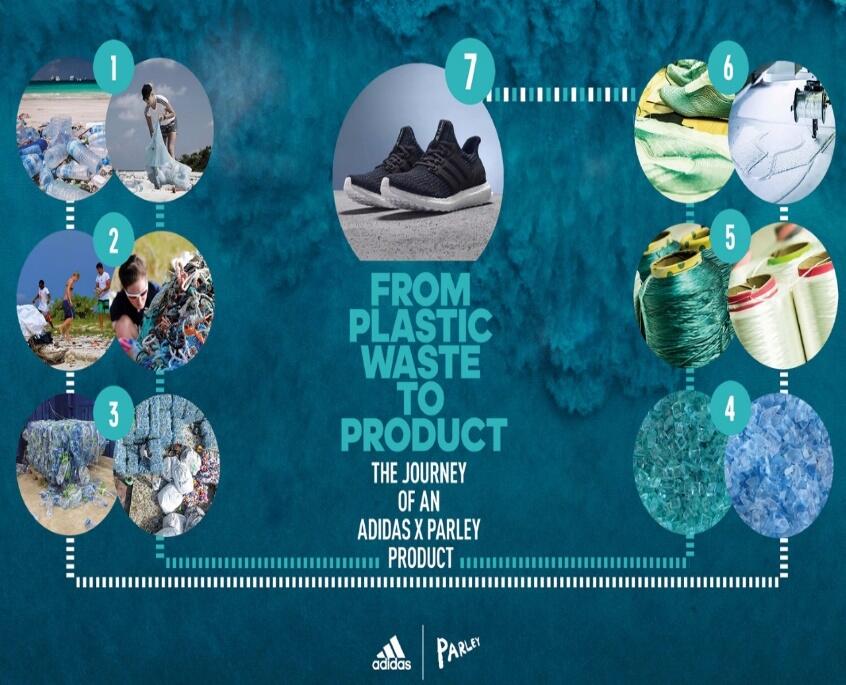

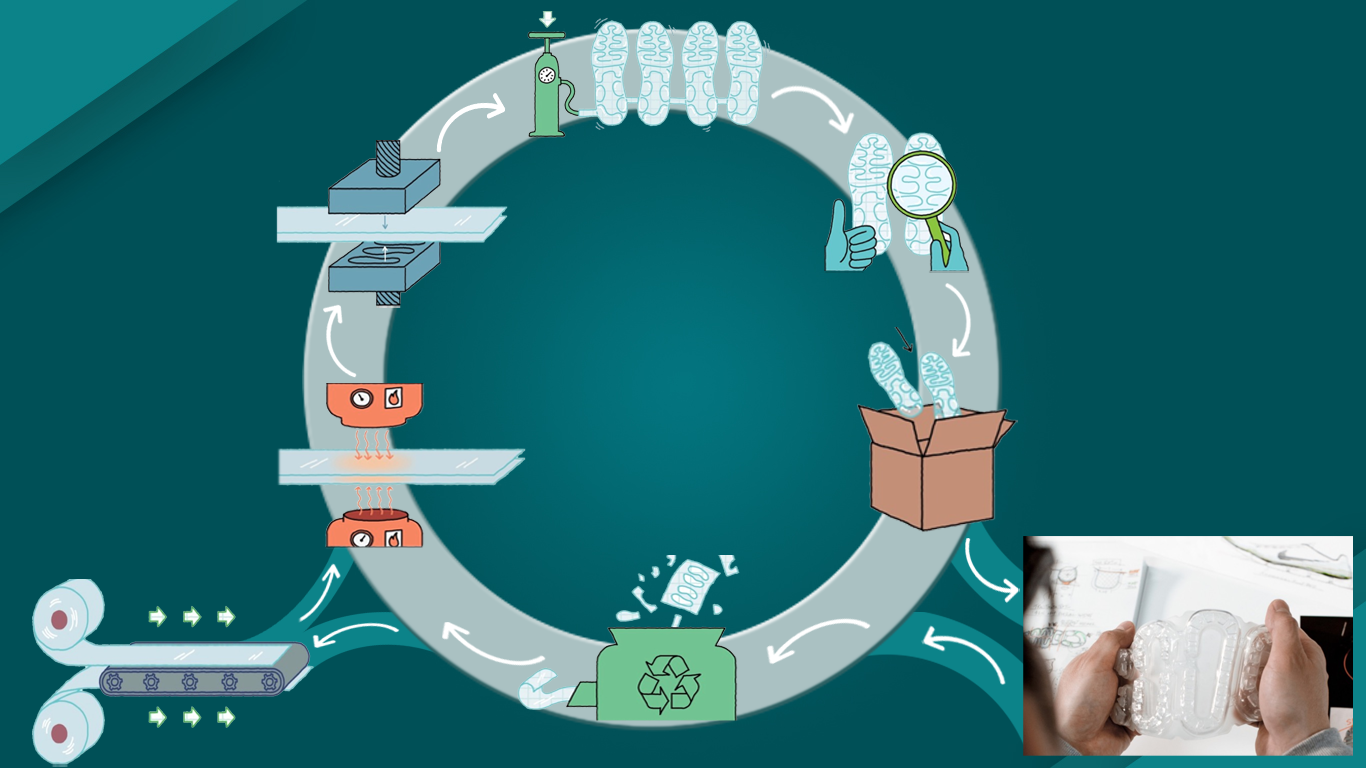

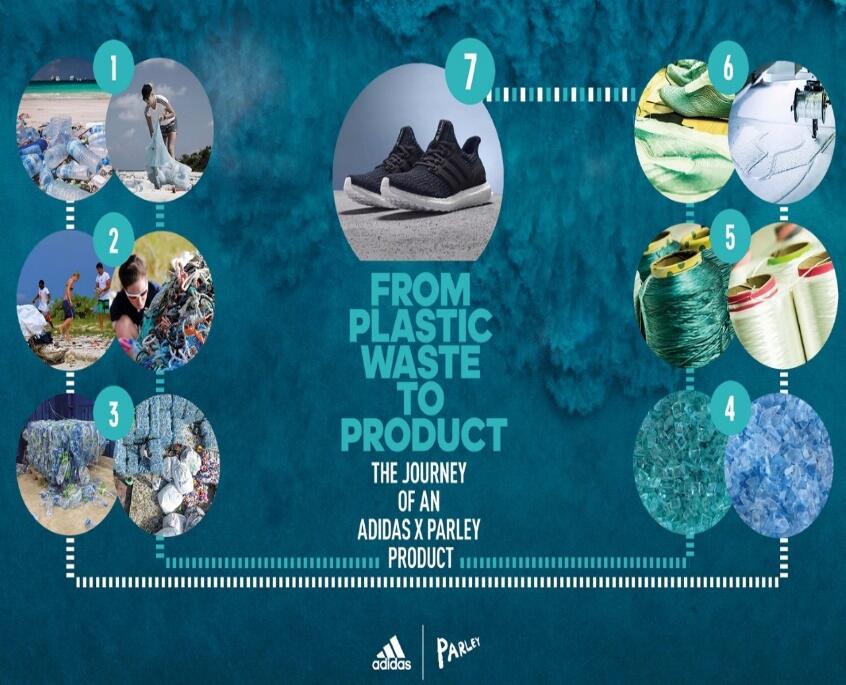

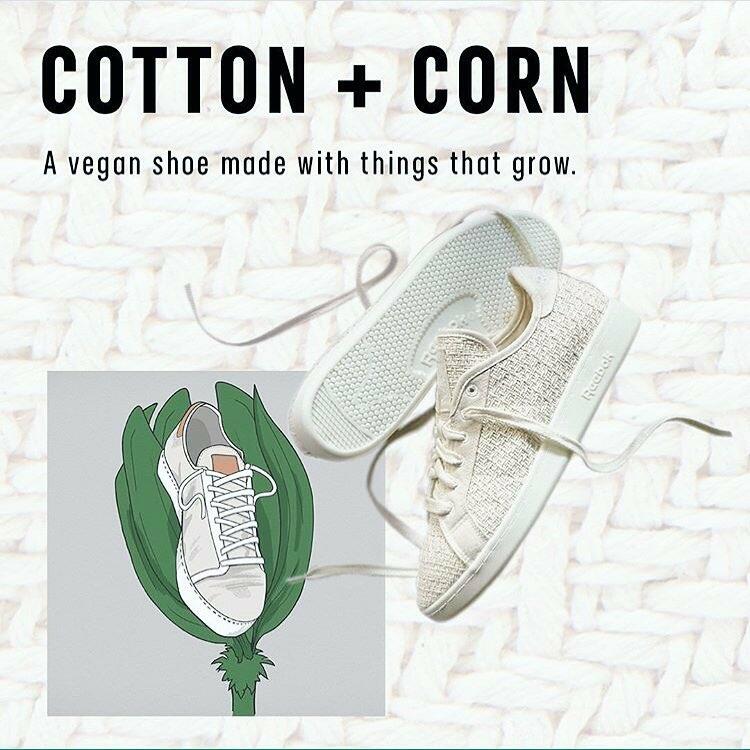

Their cooperation with Parley allows Adidas to use recycled ocean plastic and yarn to produce new products branded as Parley x Footwear (PxF), (Amir, 2018). Adidas also introduced Plant-Based Footwear (P-BF) in its strategy, which increased its CSR perception. This quality mark sets requirements for more environmentally friendly production (Milieu Centraal, 2019). Nike, however, pursues sustainability by reducing the level of toxins released from its production lines.

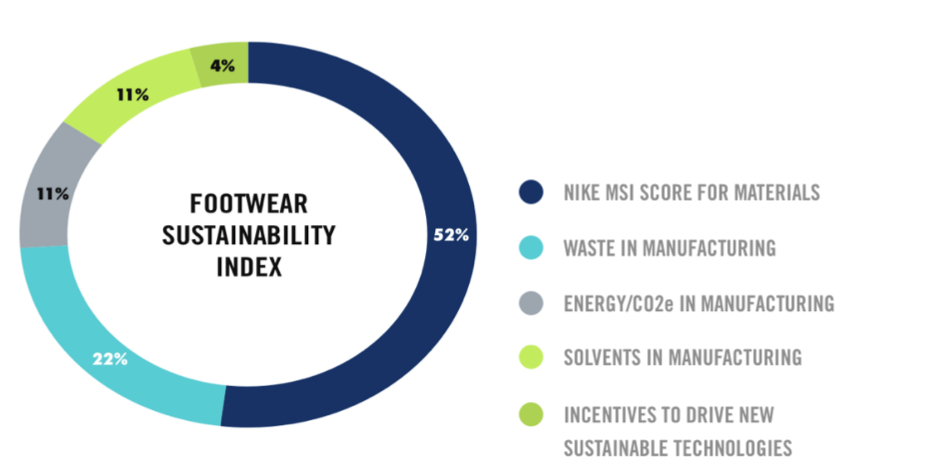

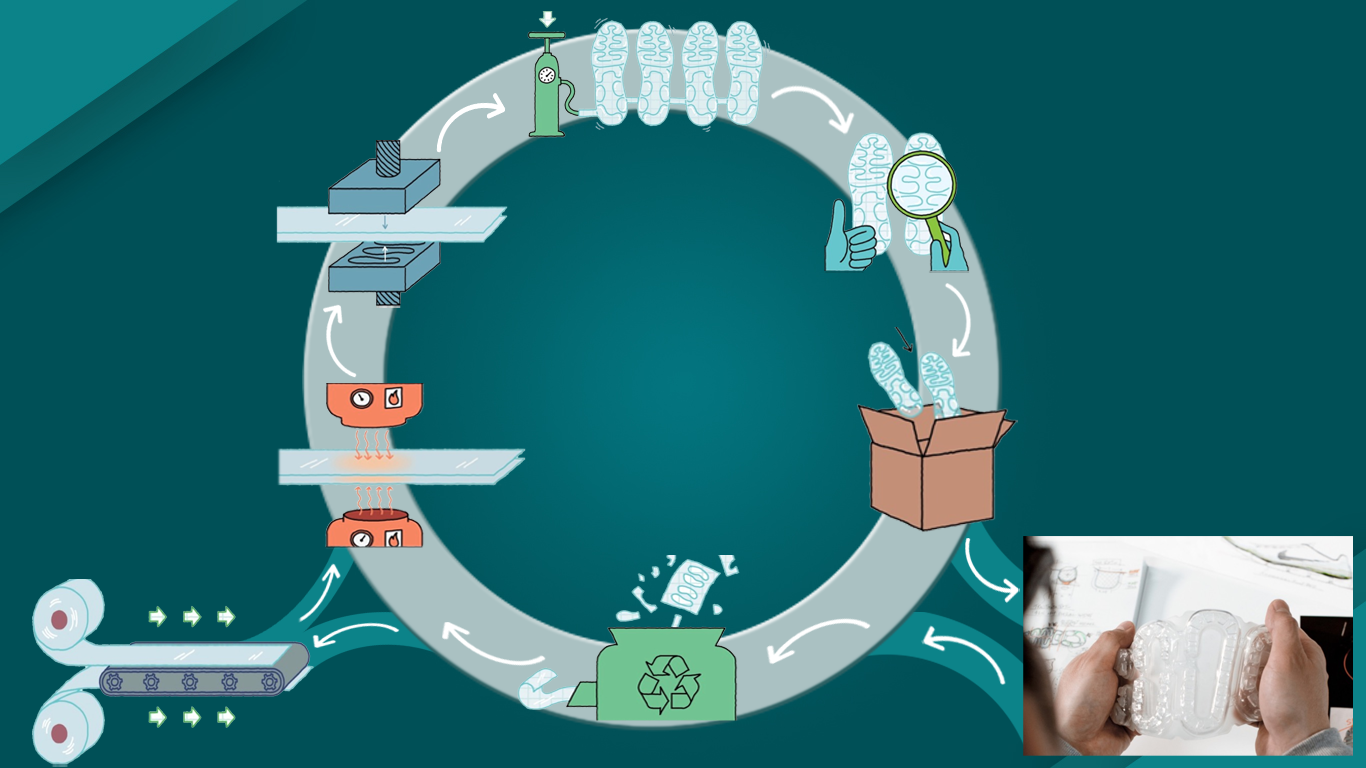

By using the considered index, designers can manage the environmental effects of shoes throughout the design operation. Nike is embracing its strategy with green initiatives. The company introduced the Footwear Sustainability Index (FSI) and the Air-Sole Innovation (ASI), allowing the company to measure the environmental impact of each product (Epstein, Buhovac, & Yuthas, 2010; Nike, 2018).

These companies have earned sizeable loyal customer bases because of their sustainability efforts (Amed et al., 2017). According to Choi and Ng (2011), brand loyalty relates to product quality; however, the existence of sustainable practices is the second-highest reason consumers return to a specific brand. Thus, fashion companies can fiercely compete in their market by implementing sustainability into their strategy.

In addition to the fact that more fashion companies start to embrace the importance of sustainability in their business strategies, sustainable consumption behavior among consumers also increases. In other words, the willingness of socially responsible consumers to purchase green products improves. A green product satisfies consumers’ needs without adverse effects on the environment (Joshi & Rahman, 2015).

Green purchasing behavior plays a significant role in protecting the world from pollution. Therefore, consumers are encouraged to choose green consumption behavior. Several studies have shown that sustainability practices by fashion firms play a dominant role in purchasing decisions in most consumers. However, young consumers separate sustainability from fashion. According to Annamma, Sherry, Venkatesh, Wang, and Chan (2012), although youngsters perceive the essence of sustainability, they do not consider sustainable fashion as the main factor in their purchasing decisions (Aziz & Yani, 2017). Thus, most consumers do not pay much attention to the sustainability aspect of the products they purchase.

Several barriers hinder consumers from considering green products in their purchasing decisions (Wunker, 2017). Fashion companies need to know these barriers first and then understand how to communicate and attract green consumers. One barrier is the consumers’ skepticism (Bonini & Oppenheim, 2008), which is defined as “the consumer’s tendency to question any aspect of a firm’s activities” (Morel & Pruyn, 2003).

Consumers’ skepticism appears when firms spread ambiguous environmental information regarding the sustainability initiative and environmental performance. A study by Joshi, Sheorey, and Gandhi (2019) suggested that consumers’ skepticism on green products appears from mislabeling, misinterpretation, and misrepresentation of green products. Therefore, skepticism prevents customers from purchasing green products despite having favorable intentions.

One essential aspect of CSR is preventing skepticism (Fuentes, 2018). Kwong and Balaji (2016) assert that skepticism harms consumer purchase intentions. Nevertheless, there is a need for a deeper understanding of how skepticism affects the green purchasing decision. Fashion firms need to overcome skepticism as it influences consumers’ purchasing decisions, which can be disadvantageous to the overall company’s performance (Anuar, Khatijah, & Mohamad, 2013).

Significant differences exist between companies that produce two main footwear segments: sports footwear sneakers and dress shoes. The sports footwear industry has dramatically become the most recent casual “uniform,” contributing to the booming trend of “athleisure” (Pasquarelli, 2014). According to Ell (2018), the sales of women sneakers increased in the United States by 37% in 2017. The level of competition is rising among fashion companies, and there is an increasing demand for sustainability in the supply chain. Therefore, the requirements of sustainability regarding environmental and social aspects are becoming stricter for manufacturers (Chopra & Meindl, 2016).

Problem statement

The increasing level of competition among companies has made sustainability a critical aspect of the fashion industry. Consequently, more companies have been compelled to adopt sustainability in their business operations. The compulsion creates a mismatch between the trend of sustainable development and the way fashion firms operate when they do not adopt a sustainable CSR strategy. Therefore, there is a kind of moral pressure on firms to be sustainable.

However, the majority of consumers do not see sustainable fashion as a priority and competitive strategy (Annamma et al., 2012). A study by Joshi and Rahman (2015) identifies an attitude-behavior-gap, which represents a weak link between the positive consumers’ attitudes regarding green consumption and the actual purchase behaviors. In essence, consumers do not have a crucial motivation to purchase green products (Annamma et al., 2012; Kirmani & Khan, 2016).

The apparent problem is that fashion companies adopting sustainability practices might incur losses because consumers would be unwilling to buy these products. In addition to the insufficient intention to purchase green products, consumer skepticism towards sustainability practices of fashion companies is intensifying. According to Bronn and Vrioni (2001), since firms engage in CSR and sustainable development, consumer skepticism is rising. Similarly, consumers might shift to another brand or spread negative WOM when they doubt the greenness of footwear companies, leading to a negative impact on the company’s reputation (Shim & Yang, 2016; Choi & Choi, 2014).

An insight into the consumers’ perception of sustainability practices from fashion companies is necessary to change this ‘negative attitude’ in consumers’ behavior. However, the adoption of sustainability practices creates a challenge for fashion companies, such as Adidas and Nike, as clear communication to consumers is necessary to avert the generation of skepticism. Therefore, Adidas and Nike are two companies that this study focuses on because they experience the problem of adopting sustainable green strategies. Appendix 1 shows further information about their CSR practices and sustainable lines.

Research aim

The purpose of this paper is to study consumers’ perceptions of the sustainability practices of Adidas and Nike. This paper aims to develop insights into how corporate reputation shapes consumers’ skepticism, which in turn influences CSR motivation, green advertising, green products, purchase intentions, and negative WOM intention. Following from this purpose, the research question formulated in this paper is: What is the impact of consumers’ skepticism regarding CSR practices (of Adidas & Nike) on the green purchasing intention, CSR motives, green advertising, green products, and the negative WOM intention in the sneakers industry? As the scope of this study, sustainability practices of Adidas and Nike comprise of (PxF, PBF, FSI, and ASI).

The results of this study provide input to the management of these two companies to profile their CSR strategy effectively. By researching this, Adidas and Nike would gain more knowledge to improve their communication plan to reach the ‘green consumers’ and increase their awareness with the view to make them purchase environmentally friendly products.

Structure of the research

To achieve the research purpose, the study identified different barriers to buying sustainable sneakers. Specifically, the study pinpointed the most critical barriers to get an insight into consumers’ doubts on sustainability practices discussed in the literature review section, with several theories relating to varied topics: dimensions of sustainability, barriers towards sustainable consumption, consumer perception of CSR, consumer purchasing behavior, WOM intention, and firms’ reputation. From the list above, the most important concepts were operationalized into variables that associate with other variables in the conceptual model.

Furthermore, several hypotheses were formulated based on the outcomes of the literature review. Second, in the methodology section, a quantitative research method was used with the questionnaire as a data collection instrument. Third, the results presented the essential statistics and the outcomes from the hypotheses. Subsequently, the study identified the limitations and offered recommendations for further research. Finally, the conclusion provided answers to research questions and recommendations for Adidas and Nike to improve their CSR strategies.

Literature review

Dimensions of sustainability

In the modern world, sustainability is an essential factor that determines the success of organizations (Haanaes, 2016). Several global fashion companies, including Nike and Adidas, have introduced CSR initiatives (Payseno, 2018). According to a study by Dahlsrud (2008), the available definitions of CSR consistently refer to five dimensions. In this study, the definition from Crane, Matten, and Spence (2013) is that CSR “the way organizations combine economic, social, and environmental concerns into their values and operations in a transparent and accountable manner”.

Oberseder, Schlegelmilch, and Murphy (2013) assert that the environmental domain is the core aspect of CSR because it protects and preserves resources that societies rely on their existence. CSR is also integral to long-term business growth and success. CSR enables companies to optimize the utilization of natural resources through the protection of the environment, reduction of wastes, and reuse of materials (Benn et al., 2014). As evident, the definition emphasizes both the social and environmental imperatives, which are relevant to this study.

Williams and Millington (2004) define sustainable development “as the development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” There are three significant dimensions of sustainability (triple P), which represent people, planet, and profits. Triple P dimensions are integral aspects of sustainability because “People link to the dimension social responsibility, planet links to the dimension environmental responsibility, and profit links to the dimension economic growth” (Govindan et al., 2013).

These three dimensions can be referred to as the term CSR. Singal (2014) established that companies that adopt CSR practices that focus on sustainability perform better and are more competitive when compared to other companies. The fashion companies Nike and Adidas have implemented this triple P in their CSR strategy. Both companies introduced green sneakers made in an environmentally responsible way by abating adverse effects on the environment in the production process.

This focus on sustainability is an excellent start to be socially and environmentally responsible; however, it is also vital that this change in attitude would contribute to the development of a company’s economy. Previous studies (Barbarossa & Pastore, 2015; Bonini & Oppenheim, 2008; Young, Hwang, McDonald, & Oates, 2010) have shown that consumers are not yet willing to purchase green goods, which decrease the economic growth of a company. Different barriers regarding the purchase of green goods that exist among consumers, such as distrust or a high price, are discussed in the next chapter.

Barriers to sustainability

Consumer barrier

Different barriers that affect the purchasing decision of green products exist among consumers. Currently, consumers understand the importance of sustainability, but several barriers affect their purchasing intentions (Wunker, 2017). Specifically, consumers do not prioritize to purchase ‘green fashion’ because they consider several other factors in their decisions (Annamma et al., 2012). Additionally, the study by Joshi and Rahman (2015) mentioned that there is a weak link between consumers’ green attitudes and purchasing behavior, which is referred to as the attitude-behavior-gap.

Several studies have investigated barriers that hinder consumers from buying green products (Ertekin & Atik, 2015; Barbarossa & Pastore, 2015; Bonini & Oppenheim, 2008). In this research, the barriers to purchasing ‘green goods’ were identified and determined if they apply to green sneakers. After that, studies from Young et al. (2010) and Lee (2018) compared if these barriers also apply to ‘green fashion,’ which is relevant to this study.

Barriers to purchasing green products

A previous study by Bonini and Oppenheim (2008) shows an exciting conclusion regarding the purchase of green products. The survey in this study was held among more than 7,000 consumers in eight major economies (China, France, Brazil, Canada, India, Germany, the UK, and the US). Eighty-seven percent of these consumers were concerned about the social and environmental influence of the products they buy.

Nevertheless, when it comes to buying green goods, this is a different situation. Only 33% of these consumers admitted that they buy green goods or are willing to do so. Possible reasons behind the low proportion are lack of awareness, distrust, low availability, negative perceptions, and high prices. According to a study by Ertekin and Atik (2015), barriers that hinder the purchase of sustainable products in the fashion industry include deficiency of awareness, the absence of trust, attitude-behavior gap, and high costs of sustainable goods. The deficiency of awareness in sustainability issues often acts as a barrier (Bonini & Oppenheim 2008; Williams & Millington, 2004).

In addition, consumers usually distrust green goods when they harbor doubts about their ‘greenness’ (Ertekin & Atik, 2015; Goh & Balaji, 2016). For instance, ambiguous and contradictory messages can lead to confusion about the social and environmental consequences of purchases, resulting in consumer distrust. Crestanello and Tattara (2011) advise companies to adopt delocalization strategies to enhance the availability of green products in the market.

Barbarossa and Pastore (2015) conducted another study to find the gap between the environmental attitudes of consumers and their purchasing behavior called ‘the green purchasing gap.’ In this study, the primary purpose focused on the barriers to purchasing green goods. The study was conducted among 51 Italian consumers who were admittedly environmentally conscious; however, they did not purchase green goods, so they showed a green purchasing gap.

According to the results of this study, unavailability, buying convenience, interest, high prices, improper communication, and limited mass-media communication are six different barriers to purchasing green goods. When it comes to their study, Barbarossa and Pastore (2015) noted that most common barriers are unavailability, high prices, and improper communication. The results of this study amplify those of Bonini and Oppenheim (2008) because they indicated the unavailability of green products, improper communication, and higher prices as major barriers.

Another study by Barnhoorn (2018) focuses on consumers’ barriers to purchasing green products in the fashion industry. This study was conducted in The Netherlands among 308 Dutch students of different ages, gender, and cities. This study identified four main barriers to purchasing green goods in the fashion industry among the Dutch consumers, consisting of insufficient knowledge and awareness, the negative perception of sustainable clothes, lack of availability, and the high price of sustainable clothes. Lee and Shin (2010) established that awareness of green products has a positive relationship with the intention to purchase.

Moreover, other studies by Young et al. (2010), and Moon and Lee (2018) focused on the barriers to buying green clothing. This quantitative research was conducted in The Netherlands among young consumers between 16 and 35 years old. The study identified several barriers for purchasing green clothing, such as distrust, high price, and unavailability. In addition to prices and green attributes, consumers consider reusability, convenience, and protective ability of the packaging of green products (Hao et al., 2019). The results in these studies show some similarities regarding the barriers of buying green products in the fashion industry.

Barriers to purchasing green footwear

Next to all these five studies about barriers to the purchase of green goods, a study by Visser, Gattol, and Helm (2015) looked at how to communicate sustainable footwear to mainstream consumers can have a significant role in the buying intention. Visser et al. (2015) conducted a quantitative study with 200 adults in the Netherlands. The results in this study identified that lack of communication is considered as a barrier to purchasing green footwear, and for consumers to recognize how sustainable initiative provided by different firms makes a specific brand more sustainable than others do.

As shown in the result of this study (Visser et al., 2015), emphasizing environmental benefits has a negative effect on the purchasing intention owing to a lower perception of sustainability by consumers. The low level of perceiving sustainability has strong link to the barriers from the previous studies (Bonini & Oppenheim, 2008; Barbarossa & Pastore, 2015).

Another study by Lois and Deborah (2005) focuses on the effects of CSR and the price of green footwear on consumer responses and purchasing intention. This study was conducted in the United States among 1997 American adults from different ages, gender, education, and cities. This study identified several barriers to purchasing green footwear in the fashion industry among American consumers, for instance, little knowledge, high prices, and negative perception. Comparative analysis of these barriers to purchasing green footwear from these two studies and the previous five studies showed some similarities in the purchase of green goods.

Table 1 below shows an overview of all barriers for purchasing green goods, and all barriers for purchasing green sneakers, obtained from the literature.

Table 1. Overview of barriers for buying green goods and green footwear.

Fashion companies need to know barriers to purchasing green products for them to reach green consumers. Some of these barriers can be solved using several strategies. For instance, the barrier of unavailability can be solved by increasing the number of green sneakers available in the market and promoting consumers’ awareness of availability through the right product placement (Krishna, 2017). Martínez-Mora and Merino (2014) add that offshoring is an effective strategy that has enabled fashion companies in the Spanish markets to access its customers globally and become competitive.

The barrier of high prices can be solved by offering a lower price for such products. Likewise, discounts can be given or trade-in-allowance, which is a special form of discount, whereby consumers receive a discount when they replace old products while buying a new one (Kerin & Hartley, 2017). The barrier of distrust is complex since it is not clear what should be improved. Distrust of green fashion stems from a negative perception based on the lack of awareness and understanding (Ahmad & Sun, 2018). An insight into the perception of consumers towards green footwear in the fashion segment is necessary for firms to overcome this barrier, as discussed in the next chapter.

These barriers relate to the conceptual framework because they cover consumers’ skepticism, CSR motive, green advertising, green products, negative WOM, green purchase intention, and corporate reputation. Barriers related to consumers’ skepticism and CSR motive of companies are distrust, unavailability, lack of awareness, and negative perception of ethical standards (Ertekin & Atik, 2015).

Doubts and deceptions are barriers that affect the effectiveness of green advertising and the purchasing decisions of customers. Barriers to green purchasing associated with negative WOM are unfavorable reviews and unwillingness to recommend products to friends and relatives (Barbarossa and Pastore (2015). Since corporate reputation is a major factor that influences consumer’s purchasing decisions, distrust is one of the associated barriers (Moon & Lee, 2018).

Regarding the purchasing intention, high prices is the common barrier that discourages consumers from buying green products (Ertekin & Atik, 2015; Barnhoorn, 2018; Young et al., 2010; Moon & Lee, 2018). Given that numerous barriers prevent consumers from purchasing green products, depicting them in the conceptual model would create a complex framework.

CSR preception

Negative preception and distrust

Since the second half of the 20th century, long debate on CSR has been taking place because firms always mention social responsibility as a part of their sustainable practice (Rosenbaum & Wong, 2015). In the modern world, companies have adopted CSR practices because they have a marked influence on consumer behaviors (Alvarado-Herrera1, Bigne, Aldas-Manzano, & Curras-Perez, 2017).

However, customers fail to determine whether companies pursue this to gain profit or a genuine desire to be sustainable, a factor that plays a significant role in consumers’ perception. Perception in this study is “the process by which an individual selects, organizes, and interprets information to create a meaningful picture of the world” (Kerin & Hartley, 2017). Another important concept is the consumers’ negative perceptions, which means that consumers process information about green goods but interpret this information mostly in an undesirable way. Thus, the negative perception is one of the barriers to buying green goods based on the previous study by Bonini and Oppenheim (2008).

Consumers’ distrust could be the result of the negative perception when consumers doubt the ‘greenness’ of products. In this study, the concept ‘distrust’ is defined as the absence of confidence in others due to the fear of harm and indifference (Ahmad & Sun, 2018). Research shows that consumers usually tend to doubt social and environmental involvement since consumers’ skepticism regarding CSR practices continues to grow. According to Morel and Pruyn (2003), distrust relates to skepticism because it increases reservations among customers. It can also lead to ‘green skepticism’ in which consumers’ doubt or disbelieve environmental claims made by a company (Kwong & Balaji, 2016).

Types of skepticism

Skepticism refers to a person’s intention to question, doubt, and disbelieve (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013). This study focuses on consumers who have doubts about the CSR practices, among those offered by shoemaker companies, Adidas and Nike. Therefore, this study focused on consumers’ skepticism on CSR practices of these two companies. Kim and Kim (2016) defined consumer skepticism concerning CSR initiatives as “publics’ disbelief toward companies’ CSR practices, messages, and motives.”

There are several studies mentioned by Kim and Kim (2016) regarding consumers’ skepticism on specific CSR aspects and where they use this aspect as a single dimension, such as focusing on environmental claims even though consumers’ skepticism on CSR practices may contain even more aspects. Therefore, this study focuses on more components of consumers’ skepticism from previous studies to get a deeper understanding of consumers’ responses towards CSR practices.

Based on a study by Foreh and Grier (2003), in the area of firms’ CSR motives, consumers’ skepticism can arise. In other words, consumers can attribute self-serving motives, such as high financial performance, to a firm’s CSR motives. Customers might doubt whether companies pursue CSR practices to gain profit or achieve a genuine desire to be sustainable. Further vital component regarding consumers’ skepticism on CSR practices is the skepticism towards green marketing messages. Research by Matthes and Wonneberger (2014) argues that consumers’ skepticism towards these messages can arise through green advertisement claims.

Consumers can perceive these claims as misleading or false. To achieve successful green advertising, claim specificity is a key issue, which should include quality, informativeness, concreteness, objectivity, and strength of a green assertion. Green advertisements should include a particular environmental claim, which means specific environmental benefits and product characteristics supported by factual details. A statement without a clear explanation, such as ‘recyclable’ or ‘better for the environment’, appears as a vague claim in the eyes of consumers. Therefore, it is important to understand consumers’ skepticism towards green advertising because it debilitates green advertising credibility, and consequently lowers marketing efficiency (Bae, 2018).

Selling environmentally friendly products is perceivable as CSR practices through waste management and reduction of raw materials in the production line occur. Research of Skarmeas and Leonidou (2013) concluded that consumers mostly have doubts about the environmental claims of products. This phenomenon can refer to ‘green skepticism’ in which consumers’ doubt or disbelieve environmental claims made by a company (Kwong & Balaji, 2016).

Factually, there are some reasons for these doubts, such as the increasing number of greenwashing incidents and irresponsible environmental behavior (Kwong & Balaji, 2016). According to Parizo (2019), firms’ transparency is important to build consumer trust about the production of merchandise. For instance, showing each step in the supply chain process provides a better image in the consumers’ minds. Consumers’ skepticism towards green products is important for this study because it can be used to measure the consumers’ attitude towards the green sneakers of fashion firms.

To summarize, the results of the several studies mentioned above showed three types of consumers’ skepticism towards CSR that was used further in this research, namely: skepticism towards a company’s CSR motives, skepticism towards green advertising, and skepticism towards green products (in this study ‘green sneakers’). Firms need to overcome levels of consumers’ skepticism because a high level of skepticism can influence consumers’ purchasing decisions, which can be disadvantageous to the overall performance of a company (Anuar et al., 2013). Consumers’ purchasing decision process was discussed further in the next section.

Purchasing decision and behavior

According to Dawson (2006), purchasing behavior comprises of attitudes that determine the way consumers choose products, select brands, and undertake their shopping. A purchase decision is the result of each one of these factors; thus, it is useful for firms to collect information regarding consumers’ choices and utilize them in providing value to customers. As Dewey, (2012) mentioned “the purchase decision process consists of five different stages (Figure 1).

This study focuses on the barrier of distrust, specifically, on the consumers who have skepticism towards CSR practices. According to the reviewed literature, overcoming levels of consumers’ skepticism is an important issue for firms because this can change their purchasing behavior. A previous study by Kwong and Balaji (2016) aimed to investigate the role of skepticism in green purchase behavior. This study provides results from a study in which it has investigated whether skepticism of organic labels influences consumers’ purchasing intentions of organic products. However, the study was limited as it was conducted in Malaysia.

This study found that consumers’ skepticism of organic labels affects purchasing behavior and relates negatively to purchasing intentions (Kwong & Balaji, 2016). In this paper, fashion firms are researched, whereby the moment of buying green sneakers is important. As can be seen in figure 1, the ‘purchase decision’ is the stage of buying a product or service, which is the stage when consumers have the intention to purchase.

Considering the results of Kwong and Balaji (2016), this study examines whether the consumers’ skepticism in the footwear segment negatively affects the green purchasing intention of these consumers. The three types of skepticism mentioned above were measured and assessed to highlight if any of these forms of skepticism have an impact on consumers’ green purchasing intentions. Therefore:

- H1: Consumers’ skepticism towards a firm’s CSR motives has a negative influence on the consumers’ green purchase intention.

- H2: Consumers’ skepticism towards green advertising has a negative influence on the consumers’ green purchase intention.

- H3: Consumers’ skepticism towards green products has a negative influence on the consumers’ green purchase intention.

WOM intention and firm’s reputation

Consumers’ skepticism on CSR practices cannot only have a negative influence on their purchasing intention, but it can also stimulate the consumers’ intention to spread negative WOM (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013). When consumers doubt the greenness of companies’ products, consumers might shift to other brands or spread negative WOM, which negatively affects a company’s reputation (Shim & Yang, 2016; Ertekin & Atik, 2015). Having a good reputation is very important to increase consumers’ purchasing intentions and to decrease the level of consumers’ skepticism (Jung & Seock, 2016). Thus, the two variables “WOM intention and corporate reputation’’ is discussed in this section.

WOM intention

As mentioned above, skepticism leads to the spread of a negative WOM when consumers find marketers not trustworthy. Therefore, overcoming the level of consumers’ skepticism is necessary as it can influence purchasing decisions. Due to the increasing level of using social media platforms, the opinion of others is becoming more accessible. Consumers can share information about specific firms or products, while firms have difficulties to control this available information (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010).

WOM is defined as the willingness of an individual to spread favorable or unfavorable messages about services or products provided by firms to his or her acquaintances (Wang, 2018). Previous studies show that WOM communication can influence the attitudes and purchasing intentions of customers, as well as firms’ brand image (Balaji, Khong, & Chong, 2016). Through WOM, consumers spread their own opinion about specific products; in this way, they share their experiences so that others might use in making informed purchasing decisions. The previous study shows unfavorable product judgments trigger consumers to provide negative information about products and services.

These kinds of consumers are more likely to spread negative WOM (Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013). In the case of this study, consumers have doubts about CSR practices (CSR motives, green advertising, and green products), which fashion firms offer. These consumers might share their concerns and doubts (negatively) when they are skeptical (Hutter, Hautz, Dennhardt, & Füller, 2013). Therefore, this study focuses on negative WOM intention. The study tested if consumers’ skepticism could have a higher intention to spread negative WOM, which led to the following hypothesis:

- H4: Consumers’ skepticism towards a firm’s CSR motives positively influences the negative WOM intention.

- H5: Consumers’ skepticism towards green advertising positively influences the negative WOM intention.

- H6: Consumers’ skepticism towards green products positively influences the negative WOM intention.

Corporate reputation

Reputation plays a central role in organizations because it determines the impact of marketing strategies. The attribution theory postulates that the way customers perceive, believe, and trust CSR practices influence the reputation of organizations (Chen & Chiu, 2018). According to Kim and Kim (2016), corporate reputation has an intricate link with the perception of CSR practices. In addition, according to previous research, CSR can increase firms’ reputation only when CSR is effectively communicated. In this case, consumers might define a company as a socially responsible company (Shim & Yang, 2016).

Creating a good reputation is challenging because companies cannot directly control their reputation. Showing transparency of a firm’s action is very important, so consumers can see if it is heading in the right direction. According to Barnett (2016), the way of providing information is also fundamental to build consumers’ trust and understanding. Consumers’ perceptions towards CSR practices of a specific firm can be affected based on the existing perceptions of that firm (Elving, 2013).

A study by Elving (2013) concluded that the firm with a good reputation was seen as honest and not self-serving, on the other hand, if the firm had a bad reputation, the level of consumers’ skepticism increased. Therefore, this study investigated the ‘corporate reputation’ of the fashion companies Adidas and Nike, which in this study is defined as “an individual’s collective representation of past images of a company established over time” (Elving, 2013).

Having a good reputation is very important because a positive reputation enhances consumers’ purchasing intentions (Jung & Seock, 2016). Consumer’s skepticism might hurt the positive relationship of corporate reputation concerning the purchasing intention (Kwong & Balaji, 2016). Thus, this research studied if consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices “as a moderating variable” can change the relationship between corporate reputation and purchase intention. A moderating variable affects the strength of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable, and thus, leading to the following hypotheses:

- H7: Corporate reputation negatively affects the level of skepticism towards CSR practices.

- H8: Skepticism towards CSR practices moderates the relationship between corporate reputation and purchase intention.

Summary of literature

From the literature review, it appears that two main concepts are leading within this research: barriers for purchasing green sneakers, including distrust barrier and the consumers’ purchasing decisions. Previous studies argue that there are still negative consumers’ perceptions towards CSR practices, and consumers often doubt the greenness of products (Romani, Grappi, & Bagozzi, 2016; Skarmeas & Leonidou, 2013).

These doubts for consumers appear as skepticism, which relates to distrust barriers. An insight into the skeptical of consumers towards CSR practices from fashion firms is necessary to obtain a broader understanding of the doubts of these consumers towards CSR. The stage purchasing decision plays a vital role in this study, as it determines consumer willingness to buy a product. As this study is focusing on the willingness to buy green sneakers, it is an essential aspect of sustainability. Moreover, previous research shows that consumers’ skepticism is linked strongly to the intention of spreading negative WOM. In addition, a higher level of skeptical for consumers towards CSR practices can influence the relationship between the firms’ reputation and consumers’ purchasing intention.

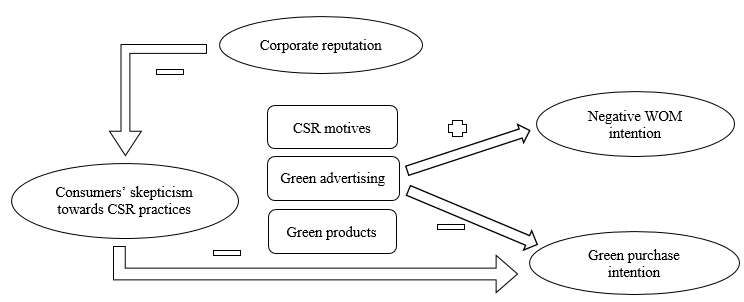

Conceptual model

Figure 2 is the conceptual model that depicts relationships between consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices, negative WOM intention, corporate reputation, and green purchase intention. Barriers that prevent consumers from purchasing green sneakers were not shown in the conceptual framework owing to the multiplicity and complexity of relationships.

The conceptual model indicates that CSR skepticism is the independent variable, which is operationalized into three variables: skepticism towards CSR motives, green advertising, and green products ‘green sneakers’. The dependent variables are the consumers’ green purchase intention, consumers’ negative WOM intention. The variable corporate reputation might have a positive relationship with green purchase intention, which can be moderated negatively by the level of skepticism towards CSR practices.

Research questions

The gap exists between consumers who are conscious of environmental issues but do not exhibit the behavior of purchasing green clothing, a term which can be referred to as “the attitude-behavior” (Joshi & Rahman, 2015). This gap could be challenging for fashion firms, as they might feel pressure to adapt to sustainable development, and if consumers are not willing to buy these green products, firms could face problems. According to the literature review, several studies show that different barriers affect consumers’ purchasing decisions, from which the barrier of distrust is further discussed. As consumer skepticism is rising, more firms ten to engage in CSR to overcome the distrust barrier (Bronn & Vrioni, 2001).

This study aims to get insight into the several types of consumer skepticisms on CSR practices from fashion firms and examines if these types influence the green purchasing intention and consumers’ negative WOM intention. This research will obtain knowledge of the two shoemakers, Adidas and Nike, regarding the reduction of the level of consumer skepticism and optimization of their communication plan to attract green consumers. To achieve this objective, the following main research question and sub-research questions are formulated as follow:

- What is the impact of consumers’ skepticism toward CSR practices on the green consumers’ purchasing intention and the negative WOM intention in the sneakers industry?

- How does consumers’ skepticism towards (CSR motives, green advertising, and green products) have an impact on the green purchasing behavior of sneakers consumers?

- How does consumers’ skepticism towards (CSR motives, green advertising, and green products) have an impact on the negative WOM intention of sneakers consumers?

- How does corporate reputation relate to consumers’ green purchasing intentions and consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices?

- What is the difference in consumer skepticism towards CSR practices between the two fashion companies Adidas and Nike?

The sub-research questions examined whether several types of skepticism influence the green purchasing intention and the negative WOM intention of consumers in the sneakers industry. Those answers aided in answering the main research question. Moreover, it can be examined whether consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices moderates the relationship between corporate reputation and green purchasing intention. Further, the study investigated if there are differences in consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices between the two fashion companies.

Methodology

Quantitative method

The study employed the quantitative approach in its research design to determine the influence of consumers’ perceptions on the sustainability practices of Adidas and Nike. Creswell (2014) holds that the quantitative approach focuses on the measurement of attributes and the use of representative sample sizes. In this case, as the study used a structured questionnaire, which measured corporate reputation, customers’ skepticism towards CSR practices, CSR motive, green advertising, green products, negative WOM, and green purchase intention on a five-point Likert scale, the quantitative approach is relevant to research design.

The quantitative method enables hypothesis testing and the assessment of the validity and reliability of a given research finding (DeFranzo, 2011). Moreover, since the study sought to deduce the influence of consumers’ perceptions on sustainability practices, the quantitative approach is an appropriate design. According to Bilgin (2017), the quantitative approach applies when researchers want to make deductive and objective inferences of research insights regarding a wide scope.

According to Bryman and Bell (2011), the quantitative method gathers numeral information that explains a deductive relationship between hypothesis and search. In essence, the quantitative method allows the generation of valid and reliable findings that are generalizable to the target population. The paradigm of positivism was employed because it considers every thought or conclusion in an objective way (Collis and Hussey, 2003). Thus, the positivist paradigm offers an effective link to the quantitative method in this study.

Data Collection

In line with the quantitative method, structured questionnaire was used in the collection of data from sampled participants who represented the target population of the study. The duration of collecting data from respondents using the structured questionnaire respond was approximately one month from the 15th of September until 14th October 2019. The questionnaire contained eight parts relating to the dependent and independent variables from the conceptual model. Moreover, a part of the questionnaire consisted of the demographic attributes, namely, age, gender, nationality, and sneakers’ expenses, which were necessary for group comparisons.

The two shoemakers (Adidas and Nike) were the focus, with their PxF, PBF, FSI, and ASI sustainability lines of green sneakers. By the use of the questionnaire, these sustainability lines were tested by consumers in the Dutch footwear segment based on their levels of skepticism on CSR practices. In addition, the study tested if these variables have an impact on consumers’ purchasing intention of green sneakers and the negative WOM intention. A cross-sectional survey was chosen to identify these relationships. The survey questions, including multiple-choice questions, were formulated with an online tool ‘Google Form’ and then spread through social media channels and word-of-mouth across Dutch Universities. The questionnaire was spread in the English language for the participants to understand it.

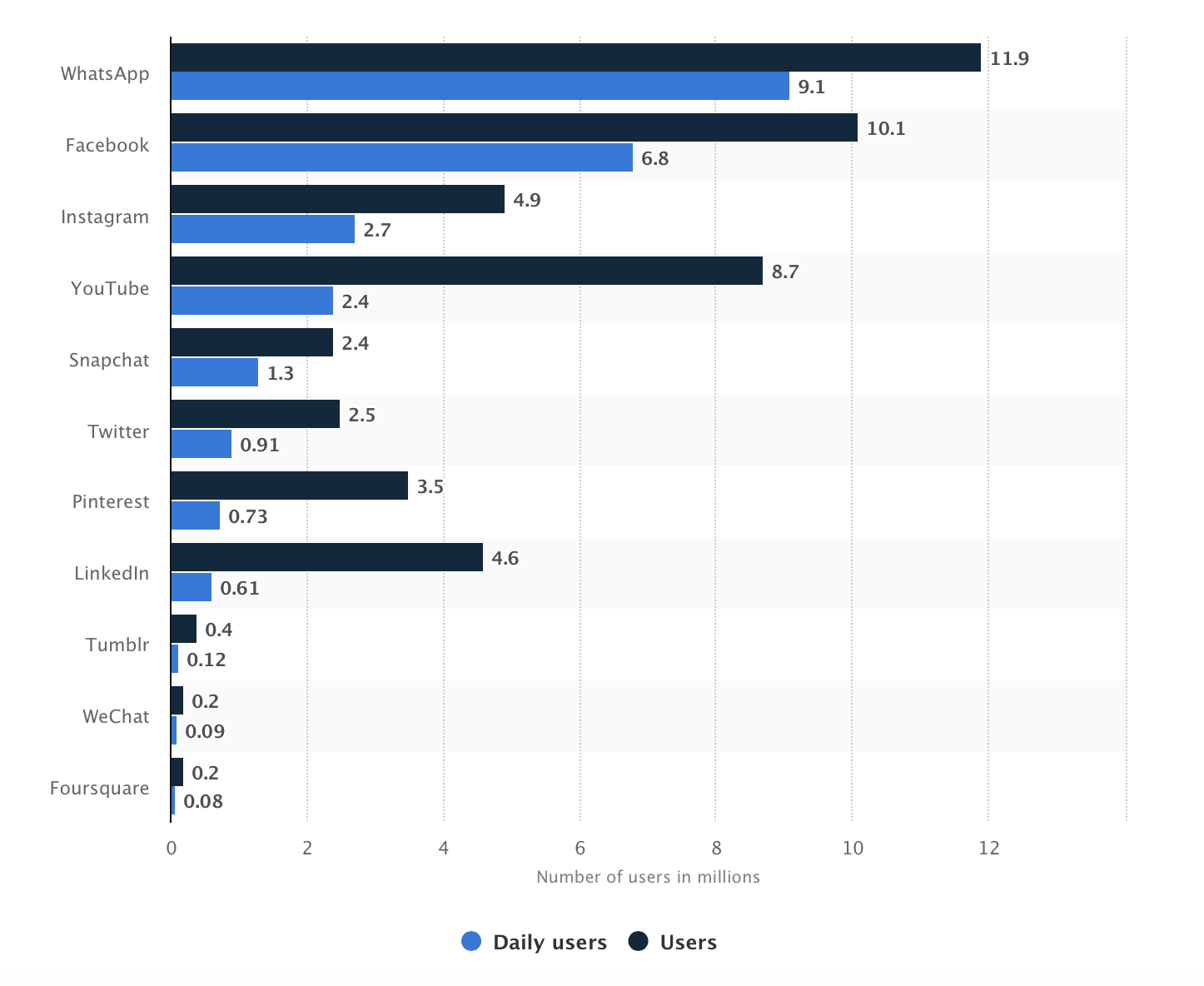

This research used social media platforms, such as Facebook and WhatsApp, as they are the most used platforms in The Netherlands (Statista, 2019) (Appendix 2). To spread the questionnaire, a hyperlink was created and distributed through Facebook and WhatsApp to consumers between 18 and 35 years-old who live in the Netherlands. A message on the researcher’s personal Facebook and WhatsApp account was written to find respondents and spread in different groups in these two platforms. With the help of these tools, the data was collected and coded into the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software for statistical analysis (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Measurement of variables

Established scales were used in this study to measure the variables, including the questionnaire (Appendix 3). Demographic data were collected from all the participants by asking questions regarding their gender, age, nationality, and sneakers’ expenses. The demographic variables were measured in categories. Gender was measured by the two categories

- = male,

- = female.

In terms of the variable age, the following four categories are provided

- = 18-22,

- = 23-29,

- = 30-35 and

- = other.

To determine if participants were significant customers of green products, expenses of a pair of sneakers were measured by four categories namely

- = less than €40,

- = between €40 and €150,

- = between €150 and €200,

- = more than €200.

These categories are based on the average monthly income statistics from the Central Bureau of Statistics (2018). All the respondents lived in the Netherlands; however, they had different nationalities. Thus, nationality was measured with one question by the following categories:

- = Dutch

- = Other.

The second part of the survey was designed to measure the overall consumers’ skepticism towards CSR practices and the three types of skepticism towards CSR, which are skepticism towards CSR motives, green advertising, and green sneakers. A three-item Likert scale was adopted from Skarmeas and Leonidou (2013) and used to measure the respondents’ level of skepticism towards CSR practices. The scale of Matthes and Wonneberger (2014), consisting of four Likert items, was used to measure skepticism towards green advertising on a five-point measure. The scale from Romani et al. (2014), which has four Likert items, was used to measure skepticism towards CSR motives.

Lastly, the scale from Danish and Naved (2016) is used to measure the skepticism towards green products, and consisting of six items, from which three items, namely consumers’ preference, feeling, and perception towards green sneakers are relevant for this study. The third part of the questionnaire related to corporate reputation, negative WOM intention, and green purchasing intention. In measuring consumers’ feelings about the corporate reputation of the fashion firms, a six-item reputation dimensions of the consumer reputation index of Feldman et al. (2014) was used in this study.

The three-item WOM scale adopted from Choi and Choi (2014) was employed to measure the negative WOM intention. In terms of green purchasing decisions, the three-item scale by Agag and El-Masry (2016) was utilized to measure this variable. Overall, the opinions of participants in terms of all these statements were measured on a five-point Likert scale “1 [strongly disagree], 2 [disagree], 3 [neutral], 4 [agree], 5 [strongly agree]”. In this way, the selected number indicated the extent of the respondent’s agreement with Likert items (Dawes, 2008). Table 2 below shows an overview of the measurement of all the variables.

Table 2: Measurement of variables.

Sample and sampling technique

The target group in this study was the young consumers between 18 and 35 years-old who live in The Netherlands and purchase sneakers in the footwear segment, including Adidas and Nike. Consumers in this age group are more open to change compared to other ages and the most enthusiastic about keeping up with the latest fashion trend (Farsang, 2014). Therefore, this target group was suitable for this study to investigate why consumers do not prefer to buy sustainable sneakers.

According to demographics, people in the age group of 18-35 years consist of approximately 4 million of the current population of The Netherlands (Central Bureau of Statistics, 2018), which is too large to investigate. With a population of 4 million, the margin of error of 5%, and the confidence interval of 95%, the appropriate sample size was calculated to be at least 384 respondents (Jani, 2014). Thus, this research considered a confidence level of 95% and a margin error of 5%.

This sample includes participants who live in The Netherlands with different gender and different level of income, who are buying sneakers from Adidas and/or Nike or intend to buy from these two companies in the future. The Netherlands has been a leading country in sustainable development, and the Dutch population has been increasingly directed towards spending on green products. Therefore, this research has chosen the Dutch population as a sample for the study since spending green purchasing has recently become recurring trend in the Dutch market. To ensure that the respondents are accessible, the questionnaire hyperlink was shared with at least 200 possible respondents using social media platforms of Facebook and WhatsApp, in addition to spreading the survey among universities using QR-code.

The writer spread approximately 600 of the QR-codes, which leads to the survey to various people who live in different cities in The Netherlands, such as Groningen, Amsterdam, Leeuwarden, and Utrecht. The participants’ locations have been chosen for the sample to be geographically representative. The questionnaire was distributed in these cities for the following reason, these cities are scattered equally between the North and South of The Netherlands. Obviously, studying one Dutch city would not be sufficient to represent the entire population. Therefore, the researcher has decided to distribute the questionnaire in scattered cities between the north and south of the Netherlands.

Data analysis

The SPSS program was used in this study to perform the analysis with the quantitative data. To eliminate redundancy and ensure validity, the data was cleaned, reviewed, analyzed, and interpreted. The eight hypotheses were formulated based on the literature review. Hypotheses 1 to 3 were tested to determine if several types of skepticism towards CSR practices influence the consumers’ green purchasing intention in the sneakers industry.

Whereas hypotheses 4 to 6 were tested to establish if numerous types of skepticism towards CSR practices influence the consumers’ negative WOM intention. Hypothesis 7 was tested to define if corporate reputation influences the level of skepticism towards CSR practices. Finally, hypothesis 8 was tested to determine if the level of skepticism moderates the relationship between corporate reputation and green purchasing intention.

Multiple regression was used in this study to test the hypotheses 1 through 6 to establish whether the independent variables (types of consumer skepticism towards CSR practices) influence the dependent variables (green purchase intention and negative WOM intention) (Mertler & Reinhart, 2017). Linear regression was used to test hypothesis 7, while moderator analysis was used to test hypothesis 8.

Control variables and controlling questions

The demographic variables are the control variables in this study. These variables were researched because previous research mentioned that they show significant differences in purchasing intention (Joshi & Rahman, 2015) and WOM intention (Wang et al., 2017). Moreover, Wang et al. (2017) add that females and people younger than 40 years old have a higher intention to spread WOM. An independent sample t-test was used to analyze whether these two variables (purchasing intention and negative WOM intention) are different between males and females. When it comes to the age group, one-way ANOVA was used to analyze whether the age of participants’ age affects the two variables (green purchasing intention and negative WOM intention).

Lastly, to ensure that the respondents live in The Netherlands and belong to the age group (18-35) as required, a control question was asked at the beginning of the questionnaire. If the participant answered this question by “Norequested sensitive information, hence posing no the survey will end. Moreover, controlling questions were asked at the beginning of the questionnaire to test whether participants read the questions correctly to increase internal validity.

Validity and reliability

To increase content validity, the survey questions were precisely formulated and well-designed instruments with appropriate questions and scope to reach the purpose of this study. In addition, a specific order was used in the survey questions so that participants could not deviate. All the survey questions were pre-tested and reviewed by experts, and then adjustments made to ensure their validity. The dependent variables, namely negative WOM intention, the three types of skepticism towards CSR practices, green purchase intention, and corporate reputation, were tested in the survey by a selection of aspects that represented varied questions for each variable. These questions together increased content validity (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

To ensure reliability, the survey was repeated and assessed if it generated the same results. Consistency of survey instruments is important in research because it ensures the reliability of results (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The Google Form used in this study to conduct the survey established that all questions in the survey were answered. Furthermore, for some of the variables used in the survey, two questions with similar focus were asked to evaluate the reliability. In this way, the researcher was able to determine if similar answers were given to reflect internal consistency. Furthermore, the reliability in the surveys was tested using Cronbach’s alpha in the SPSS program and a value that is equal to or higher than 0.7 was considered reliable. A confidence interval of 95% and a significance level of 0.05 are used for all statistical tests. In the next chapter, the results were presented.

Ethical consideration

This study ensured that it complied with relevant ethical requirements in the process of research. According to Coghland and Brannick (2014), ethics requires a researcher not to cause harm, coerce participants, distort data, or breach confidentiality. The research has minimal ethical considerations as the participants were allowed to volunteer in their participation. The questionnaire used in data collection posed no harm to respondents because it did not request sensitive information. The study also guaranteed freedom as participants were given the freedom to answer the questionnaire at their convenient places and times.

Subsequently, all participants were thoroughly explained regarding the purpose of this study and their contributions for them to provide informed consent. For privacy purposes, the study ensured that all questionnaire data were completely anonymous as the names and other personal details were not collected. To further preserve anonymity, no specific information that allows identifying the participants was added to the questionnaire. Finally, no data was published in any other work apart from this study and attributed to the researchers.

Results

Descriptive statistics (explain this part properly)

The results from the questionnaire were generated a representative number of respondents (N = 463) who participated in this study. The questionnaire was distributed in the English language for participants to understand and provide valid answers as the researcher received only one email from a participant regarding the questionnaire (Appendix 4). Out of 463 datasets, 152 were considered as not relevant and deselected in the analysis because these participants did not belong to the sample (the age group 18-35, and the living in The Netherlands, or they answered more than one of the controlling questions wrong).

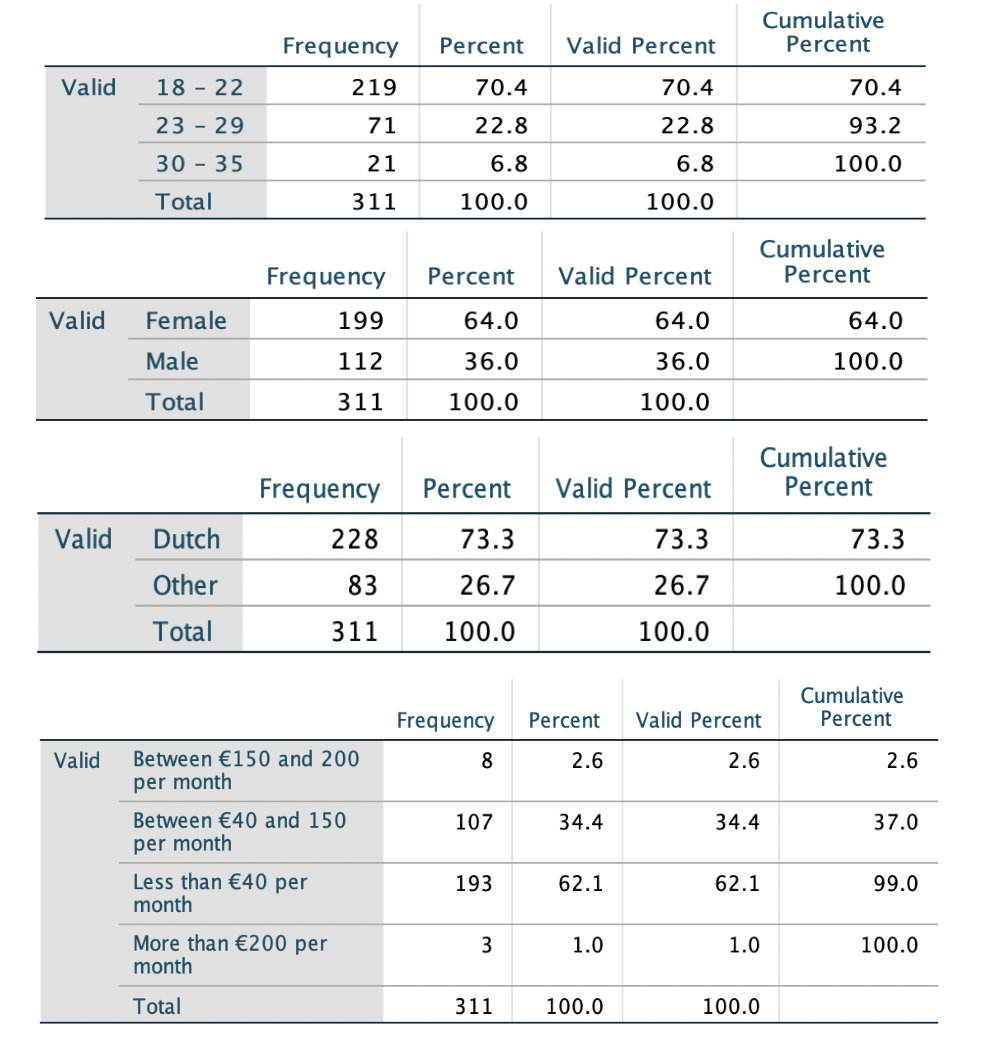

The data was cleaned further by selecting respondents who answered three or more of the controlling questions right. With the SPSS software, it was possible to exclude cases by logic syntax, making it possible to work with open controlling questions, ensuring more validity of the questionnaire. Thus, the remaining 311 respondents were collected and further analyzed. Table 3 shows the frequencies of the demographic attributes of age, gender, nationality, and sneakers’ expenses. (Calculations in details can be found in table A, Appendix 5).

Table 3: Demographics of participants.

Table 3 shows that participants comprised of 36% males and 64% females. From these samples, 73.3% were Dutch and 26.7% belonged to different nationalities. When it comes to the participants’ age, most participants (70.4%) belonged to the age group 18-22 years followed by those in the age group of 23-29 years (22.8%) and the age group of 30-35 years (36.8%). The sneakers’ expenses of the respondents were quite different.

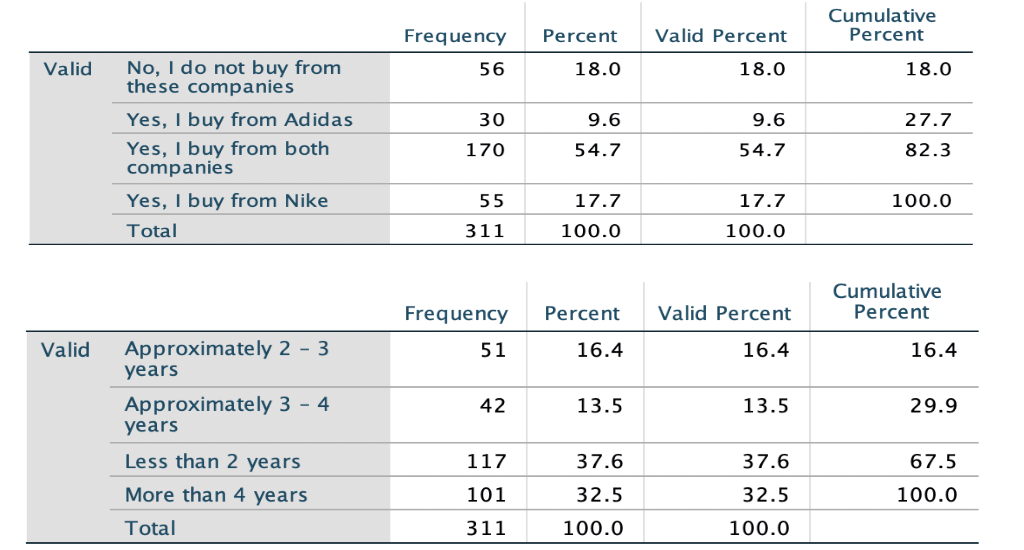

Most participants (62.1%) spend less than €40 on sneakers per month followed by those who spend between €40 and €150 (34.4%). Table 4 shows the statistics of the consumption behavior of participants. The results indicate that most respondents (54.7%) buy sneakers from both companies. Moreover, 32% of the respondents had bought sneakers from these two companies for more than four years, which means they are loyal customers to these companies. (Calculations in details can be found in table B, Appendix 5).

Table 4: Consumers’ behavior.

Construct building and Cronbach’s alpha

To analyze the data, several constructs were created by combining the questions in the survey dealing with the same topic. The reliability was checked by examining the internal consistency of each construct scale using Cronbach’s alpha (α). To test the accuracy of Cronbach’s alpha, the Likert scales were matched to ensure consistency of items negative WOM and green product intentions, which means that the ascending scale of 1 to 5 should result in the same ascending score for the construct of each separate question. The threshold for an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha was set at 0.7, and values close to it were also selected.

According to Allen et al. (2014), measured items with a Cronbach alpha of over 0.70 should be considered valid. After a construct was accepted, the questions were pooled to form a Likert scale for each variable. Moreover, different items were removed to improve the results. After computing Cronbach’s alpha for the different variables, the variables that showed sufficient reliability were selected. Table 18 shows further information about the excluded items (Appendix 6).

The following scales have been compiled by examining Cronbach’s alpha: Skepticism towards CSR practices of Adidas has three items (α = 0.630), skepticism towards CSR practices of Nike has two items (α = 0.840), CSR motives of Adidas have three items, (α = 0.808), and CSR motives of Nike have three items (α = 0.880). Furthermore, green advertising of Adidas has four items (α = 0.823), green advertising of Nike has four items (α = 0.828), green product of Adidas, two items, (α = 0.692), green product of Nike, two items, (α = 0.670), reputation of Adidas has six items (α = 0.847) and reputation of Nike has six items (α = 0.880). The purchase intention of Adidas has three items (α = 0.786), purchase intention Nike has three items (α = 0.846), negative WOM intention of Adidas has three items (α = 0.609) and negative WOM intention of Nike has three items, (α = 0.579).

Control variables (Use Total score)

Gender (mean male female together) do they have to purchase and WOM (from 1- 5 )

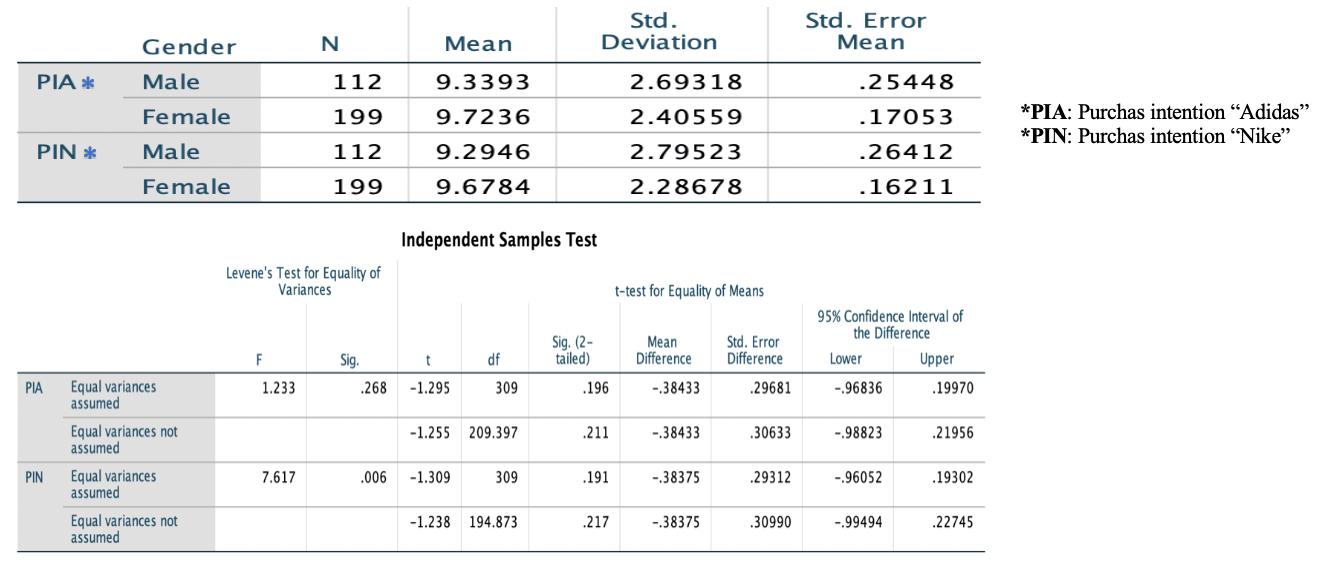

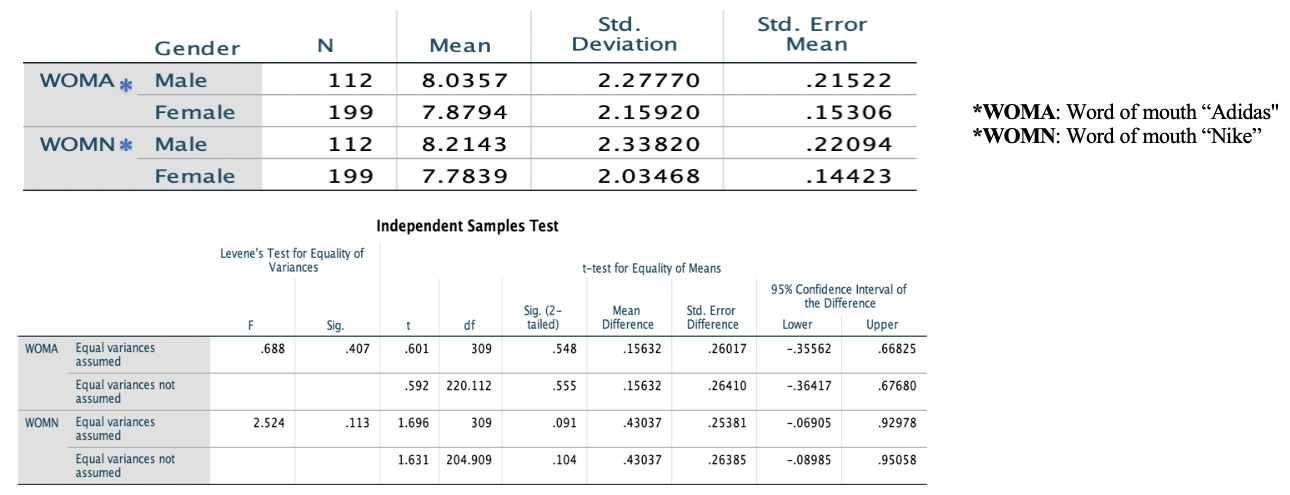

To analyze if the dependent variables of green purchasing intention and negative WOM intention were different between male and female participants, four independent-samples t-test were conducted (Tables 5 and 6) for Adidas and Nike. Descriptive statistics (Table 5) shows that the test is not significant for the company Adidas. This means that the average green purchasing intention of men does not differ from the average green purchase intention of women.

According to the statistics, both women and men have the same intention to purchase green sneakers from Adidas. On contrast, table 5 shows that the test is significant for the company Nike. Which means that the average green purchase intention of men does differ from the average green purchase intention of women. According to the statistics, women have a higher intention to purchase green sneakers from Nike than men. (Calculations in details can be found in table C, Appendix 5).

Table 5: Gender and purchase intention.

Descriptive statistics (Table 6) indicates that the test for negative WOM intention and gender for both companies was not significant, which means that the average negative WOM intention of men does not differ from that women of Adidas and Nike. (Calculations in details can be found in table D, Appendix 5).

Table 6: Gender and negative WOM intention.

Age

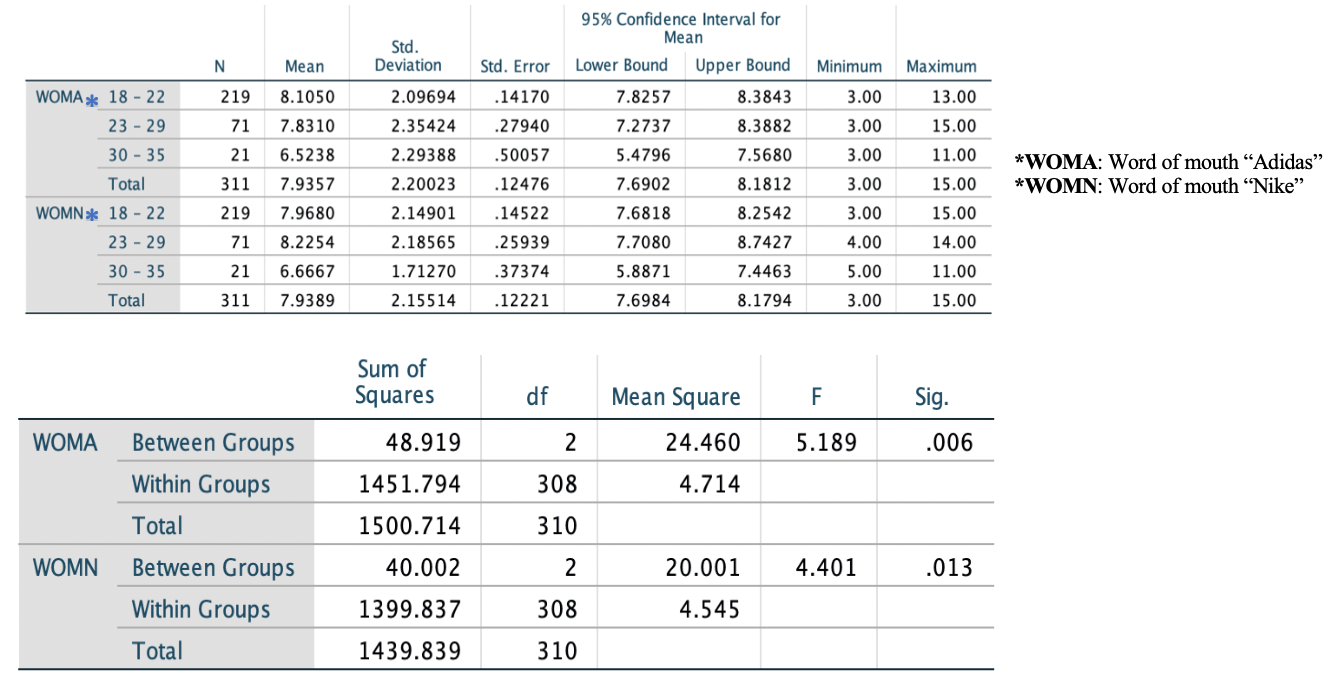

To examine whether the age variable influences the green purchase intention and negative WOM intention, the one-way ANOVA test was conducted for both companies Adidas and Nike. Table 7 shows that there is a significant effect of age on purchase intention of both companies, which means that age does influence consumers’ green purchase intention, which concludes that age does influence the consumers’ green purchase intention at Adidas and Nike. According to the statistics, participants in the age group of 30-35 years had the highest purchase intention to purchase green sneakers at both companies than the other age groups. (Calculations in details can be found in table E, Appendix 5). Include Post hoc

Table 7: Age and purchase intention.

Table 8 shows that there is a significant effect of age on the negative WOM intention for the company Adidas. Therefore, can be concluded that age does influence consumers’ negative WOM intention for Adidas. Whereas, the table shows that there is no significant effect for the company Nike. Which means that age does not influence consumers’ negative WOM intention for Nike. (Calculations in details can be found in table F, Appendix 5). Include Post hoc

Table 8: Age and negative WOM intention.

Controlling questions

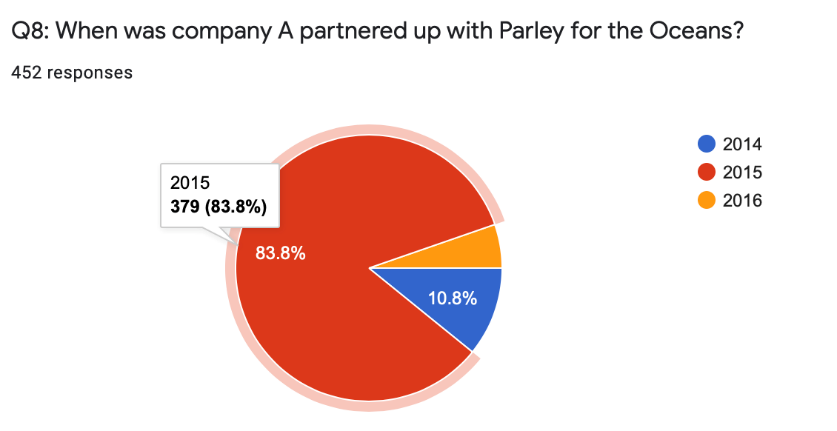

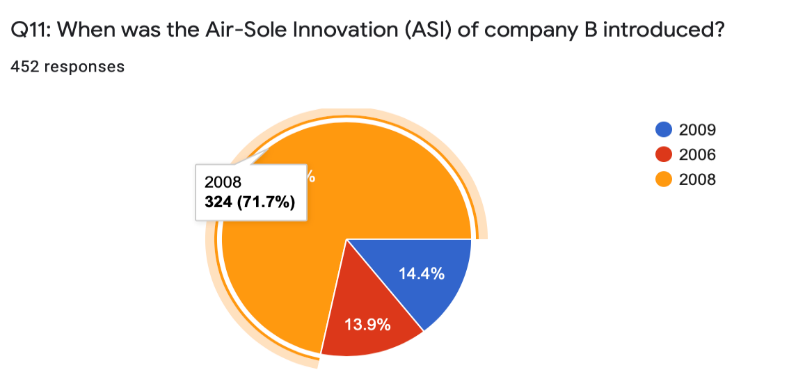

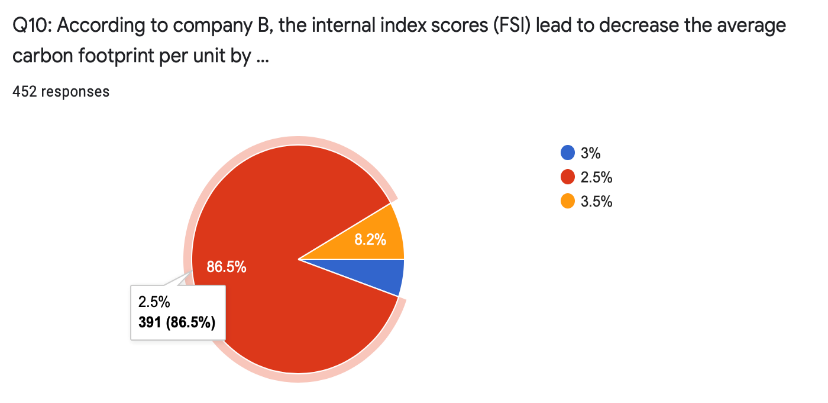

A control survey was performed to evaluate how the participants answered the controlling questions about Adidas and Nike’s sustainable practices. Question 1 asked for a specific year, questions 2 and 4 asked about the introduction of a specific sustainable initiative for both companies, and question 3 inquired about a specific percentage (all 3-point multiple-choice questions). Eventually, 311 participants were analyzed from which every participant answered three or more of the controlling questions correctly. In other words, respondents who had more than one mistake of the controlling questions were excluded from the analysis. Out of all respondents (N=463), 83.8%, 71.5%, 86.5%, and 71.7% answered questions one through four correctly, respectively (See Appendix 7).

Hypothesis testing

Inferential statistics were used to test the significance of the eight hypotheses. Specifically, multiple linear regression analyses and one-way ANOVA were used as an inferential test. Linearity, independence, homoscedasticity, multicollinearity, and normality tests were used to check compliance with key assumptions (Statistics Solutions, 2018).

Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3

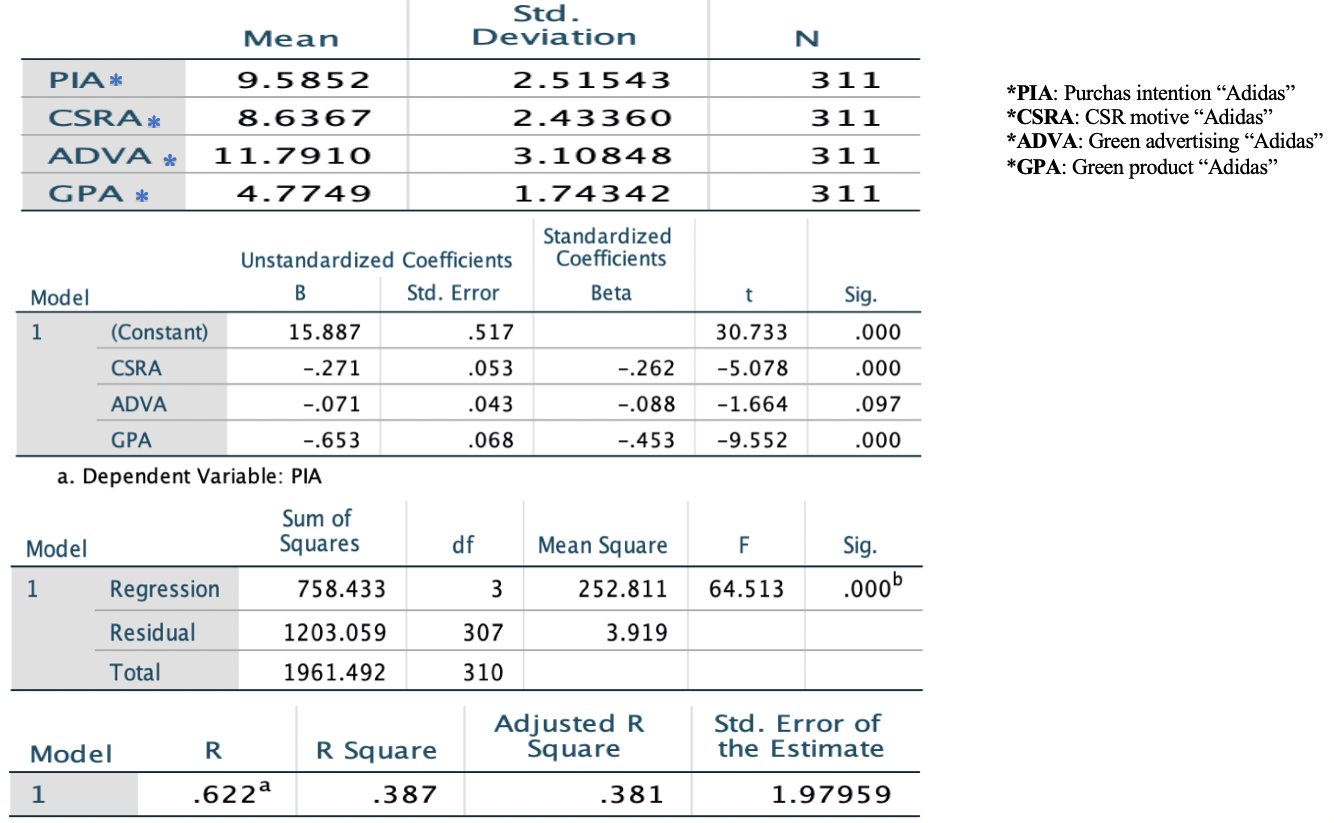

To examine whether the three types of skepticism have a negative influence on the consumers’ green purchase intention in the sneakers industry, a multiple regression analysis was used. This analysis was performed separately for both companies Adidas and Nike. Table 9 shows descriptive statistics and regression output of the influence of CSR motive, green advertising, and green product on the purchase intention of Adidas.

The results for the company Adidas show a significant model with p=0,000, R=0,622 and Adjusted R square= 0,381. Furthermore, table 9 shows that the two type of skepticism on CSR practices (CSR motive and green product) has a negatively significant effect on consumers’ green purchase intention. Based on this evidence, the two hypotheses H1 and H2 is supported that skepticism towards (CSR motives and green products) from Adidas has a negative influence on the consumers’ green purchase intention. On the other hand, table 9 shows that skepticism on green advertising has no significant influence on consumers’ green purchase intention from Adidas. Thus, hypothesis H3 is rejected for the company Adidas. (Calculations in details can be found in table G, Appendix 5).

Table 9: CSR practices and purchasing intention: multiple regression analysis “Adidas”.

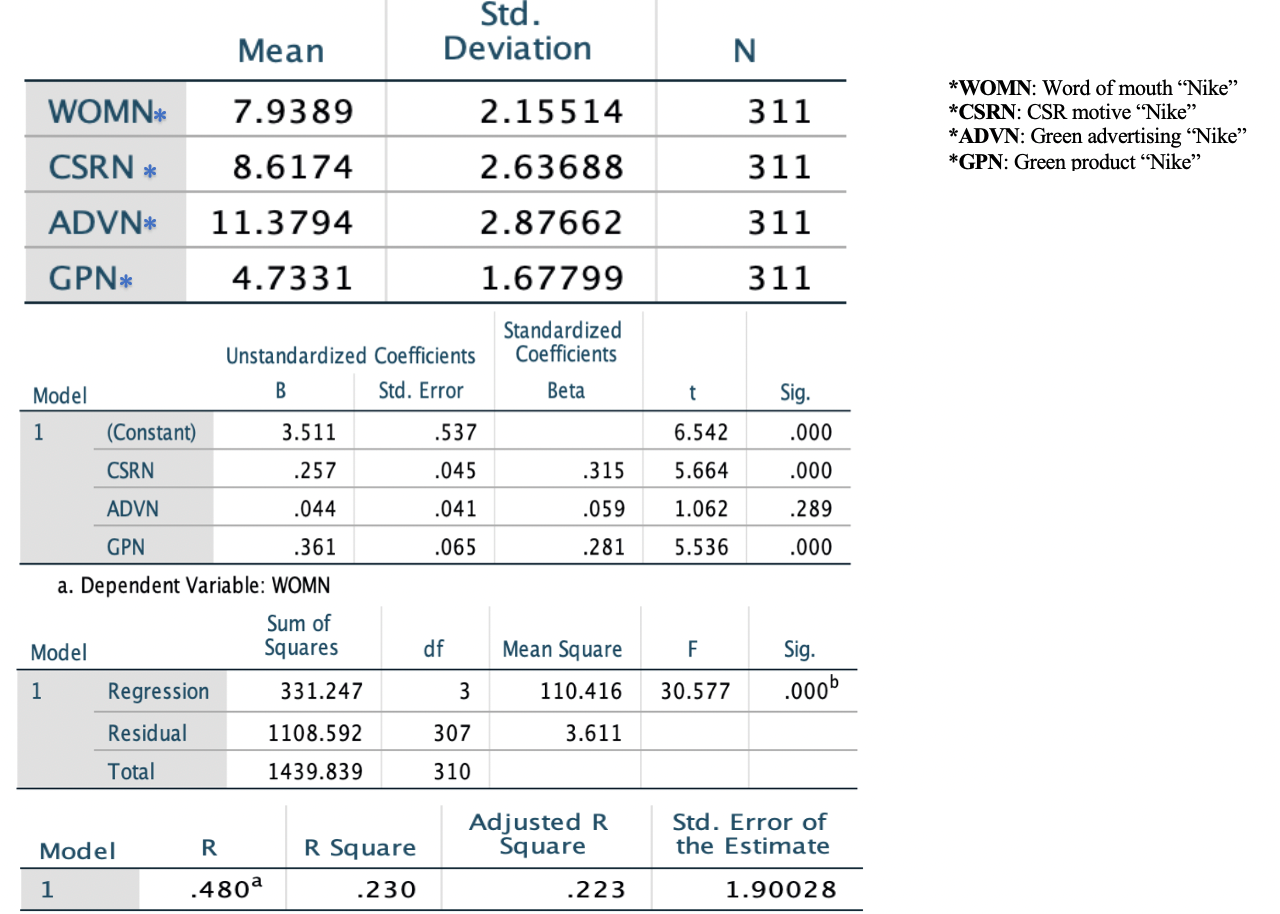

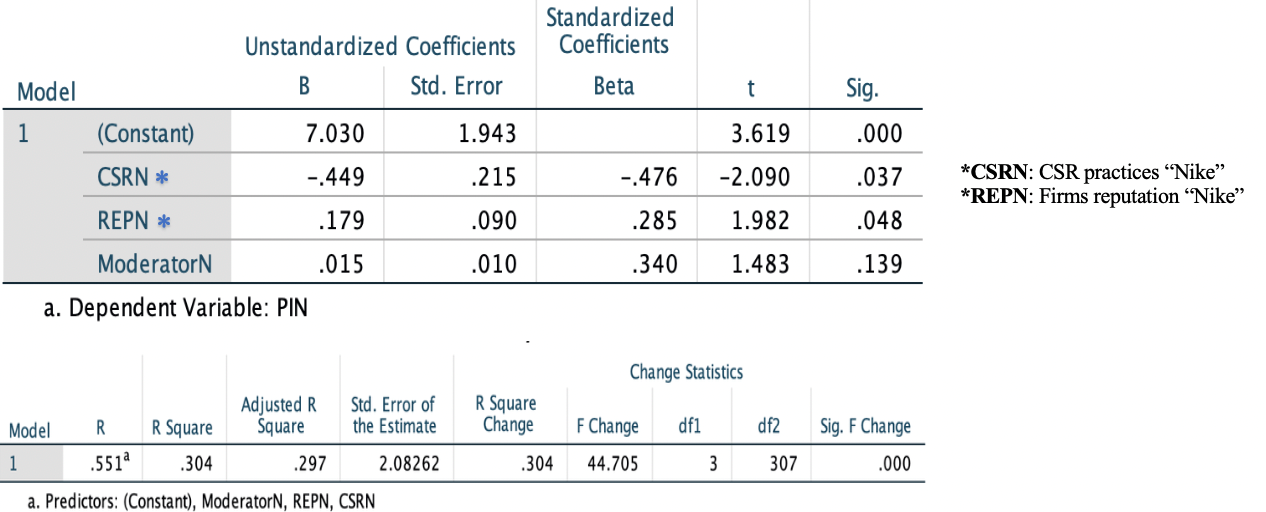

Table 10 depicts descriptive statistics and regression analysis of the influence of CSR motive, green advertising, and green product on the purchase intention of Nike. The results for the company Nike also show a significant model with p=0,000, R=0,533 and Adjusted R square= 0,277. Table 10 shows that the two type of skepticism on CSR practices (CSR motive and green product) has a negatively significant effect on consumers’ green purchase intention.

Based on this evidence, the two hypotheses H1 and H2 are also supported that skepticism towards (CSR motives and green products) from Nike has a negative influence on the consumers’ green purchase intention. On the other hand, Table 10 shows that skepticism on green advertising has no significant influence on consumers’ green purchase intention from Nike. Thus, hypothesis H3 is also rejected for the company Nike. Overall, the results indicate that the consumers are skeptical about the CSR practices from both two companies. Additionally, the results indicate that the consumers are overall a bit more skeptical about CSR practices from Adidas than from Nike. Looking at the mean of green purchase intention of both companies, consumers have a higher intention to purchase green sneakers at Adidas than at Nike. (Calculations in details can be found in table H, Appendix 5).

Table 10: CSR practices and purchasing intention: multiple regression analysis “Nike”.

Hypotheses H4, H5, and H6

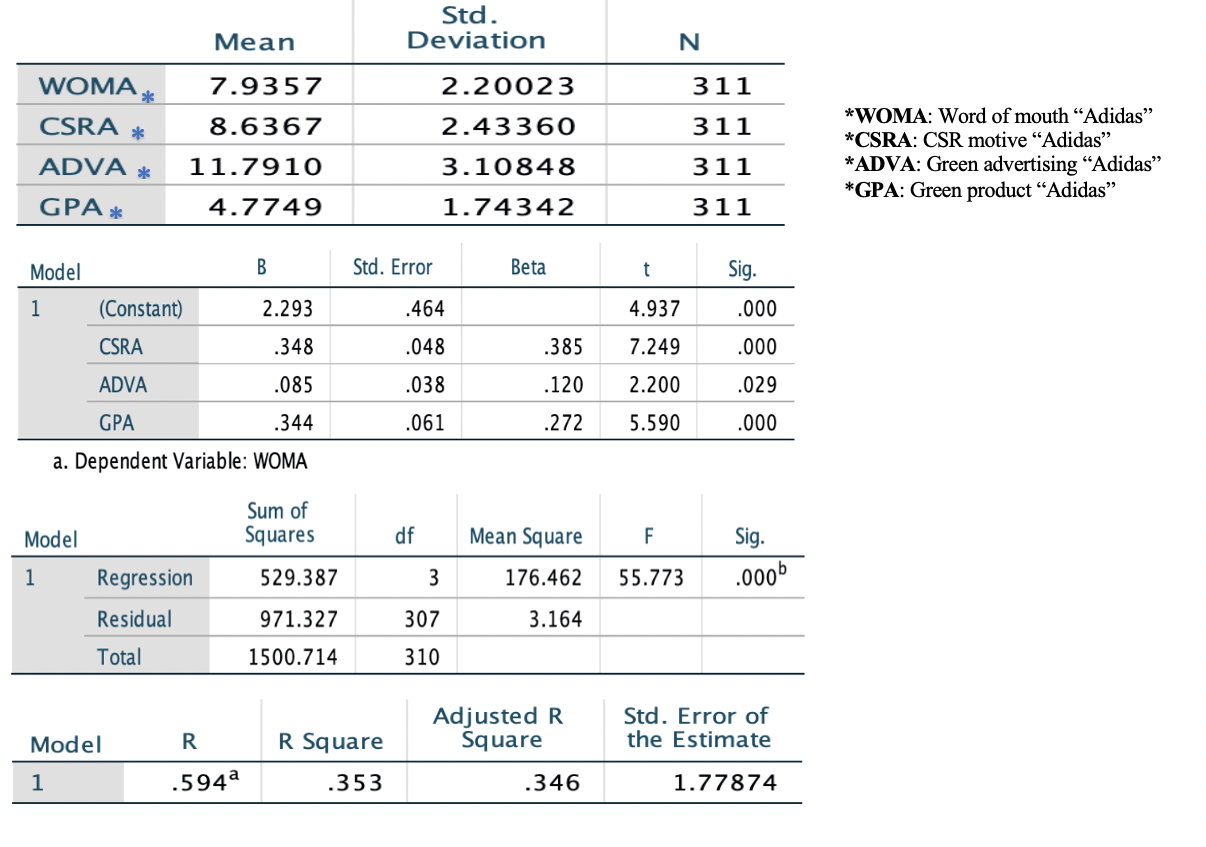

For examining whether the three types of skepticism towards CSR practices, namely CSR motive, green advertising, and green product, have positive influence consumers’ negative WOM intention (WOM) for both Adidas and Nike, a multiple regression analysis was performed. The results from the analysis about the company Adidas show a significant model with p=0,000, R=0,594 and Adjusted R square= 0,346.

Table 11 reveals that green CSR motives and green products show a positive significant effect on negative WOM intention. Therefore, H4 and H6 are supported, that skepticism towards CSR motives and green product of Adidas have a positive influence on the negative WOM intention of consumers. On the other hand, the variable green advertising does not show a significant effect, therefore H5 is rejected, that skepticism towards green advertising has a positive influence on the green purchase intention. (Calculations in details can be found in table I, Appendix 5).

Table 11: CSR practices and negative WOM intention: multiple regression analysis “Adidas”.

The results for the company Nike also show a significant model with p=0,000, R=0,480 and Adjusted R square=0,223. Looking to table 12, the variable green advertising is not significant, which means that skepticism towards green advertising of Nike does not positively influence the negative WOM intention. On the other hand, the variables CSR motives and green product show a positive significant effect on negative WOM intention.

Which means that skepticism towards CSR motives and green products of Nike do have a positive influence on the negative WOM intention of consumers. With this evidence, H4, H6 are supported, and H5 is rejected. Furthermore, table 11 and 12 reveal the mean of negative WOM intention for Adidas and Nike. This indicates that consumers have a higher intention to spread negative WOM about Nike than about Adidas. (Calculations in details can be found in table J, Appendix 5).

Table 12: CSR practices and negative WOM intention: multiple regression analysis “Nike”.

Hypothesis H7

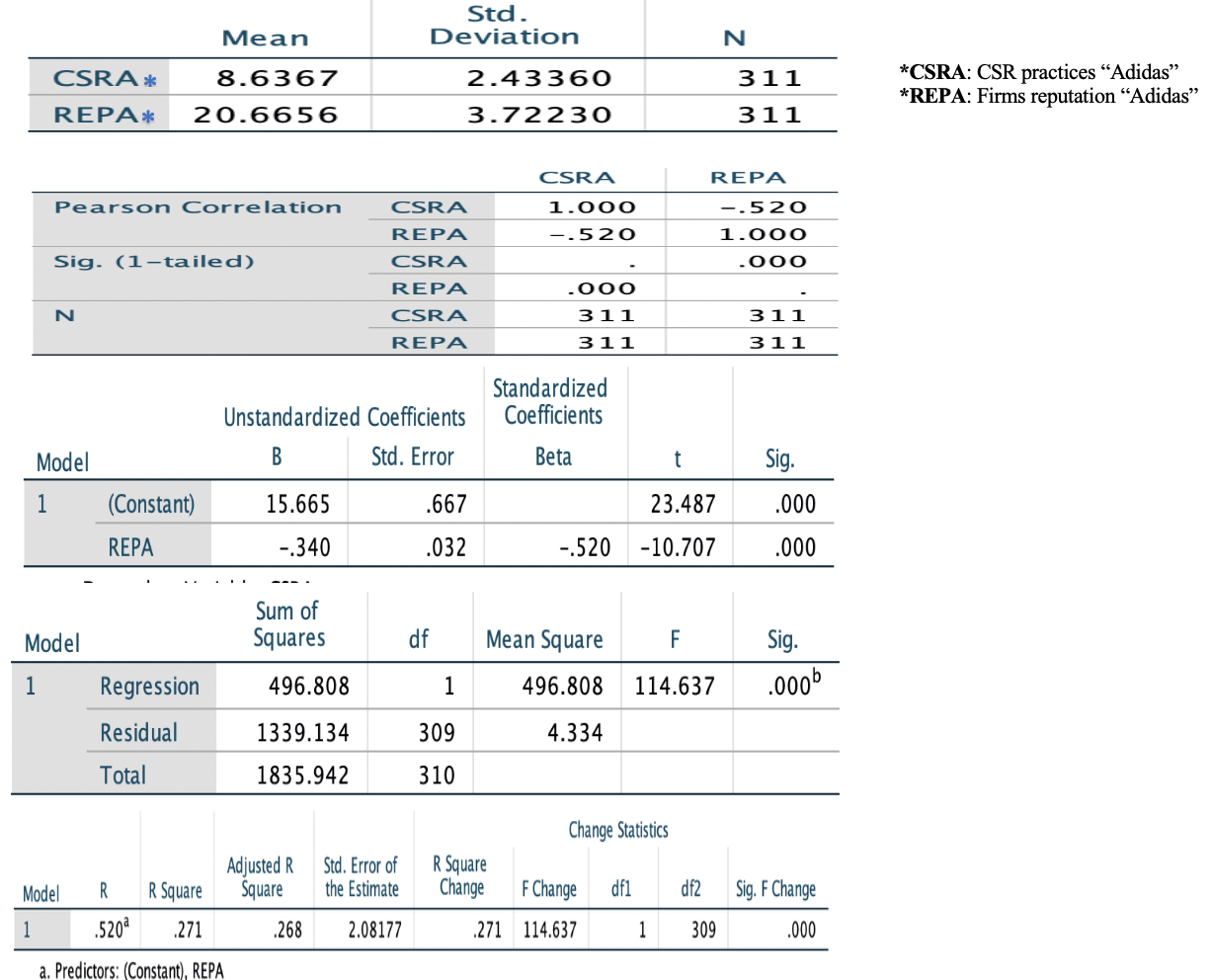

Hypothesis 7 examines whether corporate reputation has an impact on the level of skepticism towards CSR practices. The results for the company Adidas show a significant model with p=0.000, R=0,520 and Adjusted R square= 0,271. Looking at the results in table 13, it can be concluded that the corporate reputation of the company Adidas has a negative impact on the level of consumers’ skepticism, which means when the reputation of Adidas becomes higher, the level of consumer’ skepticism towards the CSR practices of the company decreases.

The correlation analysis shows that the corporate reputation and CSR practices have a moderate negative relationship, which is statistically significant. The regression coefficient shows that the corporate reputation of Adidas has a negative influence on the level of consumers’ skepticism. The coefficient means that when the reputation of Adidas increases by a unit, the level of consumer’ skepticism towards the CSR practices decreases by 0.34 units. (Calculations in details can be found in table K, Appendix 5).

Table 13: Corporate reputation and level of skepticism: linear regression analysis “Adidas”.

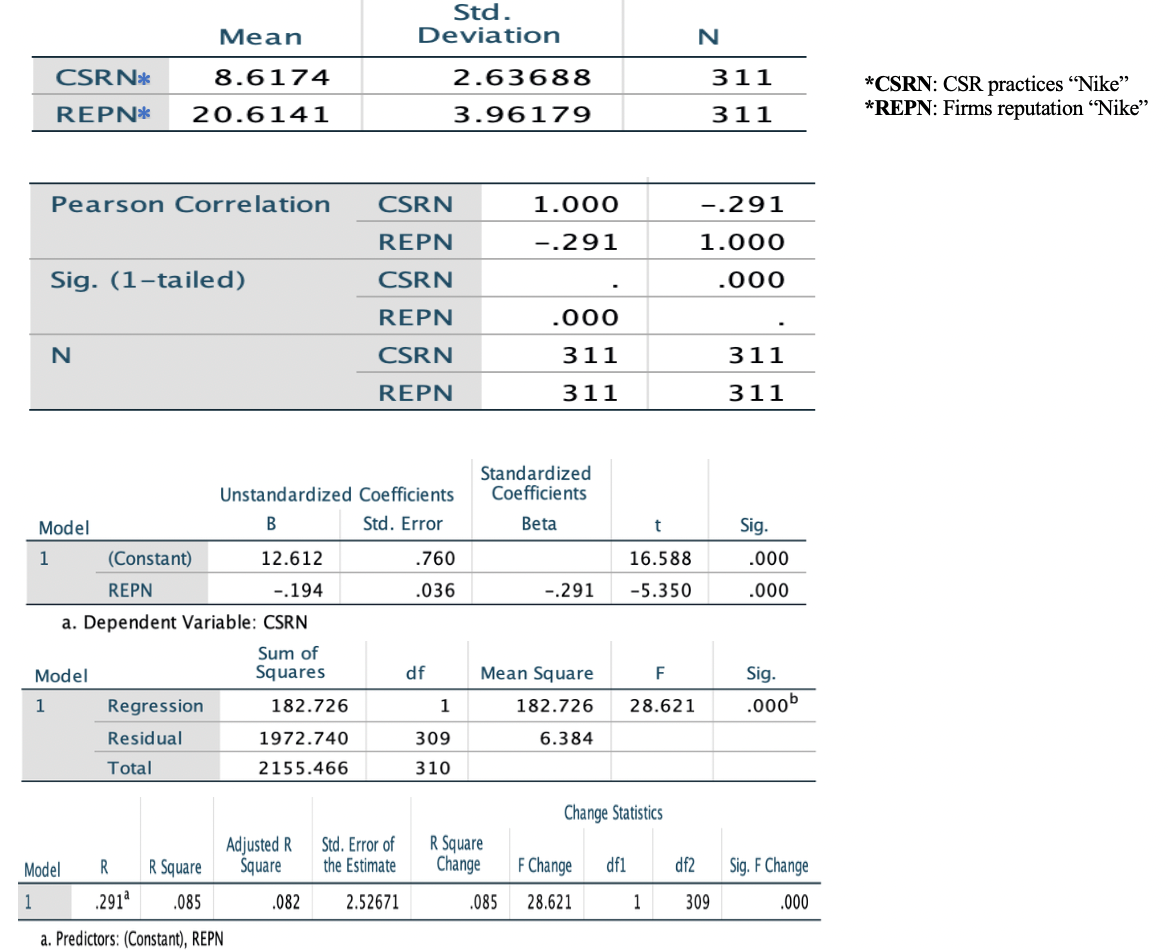

Also, the results for the company Nike show a significant model with p=0,000, R=0,291 and Adjusted R square=0,085. Looking at the results in table 14, it can be concluded that the corporate reputation of the company Nike has a negative impact on the level of consumers’ skepticism, which means when the reputation of Nike becomes higher, the level of consumer’ skepticism towards the CSR practices of the company decreases.

Therefore, it can be concluded that the corporate reputation of Nike has a negative influence on the level of consumers’ skepticism. The coefficient means that when the reputation of Nike increase by a unit, the level of consumer’ skepticism towards the CSR practices decreases by 0.194 units. Thus, the evidence supports hypothesis 7 that the corporate reputation has a negative effect on the consumer skepticism towards CSR practices of both companies. Furthermore, Tables 13 and 14 show the means of the corporate reputation and CSR practices of both companies are comparable. (Calculations in details can be found in table L, Appendix 5).

Table 14: Corporate reputation and level of skepticism: linear regression analysis “Nike”.

Hypothesis H8

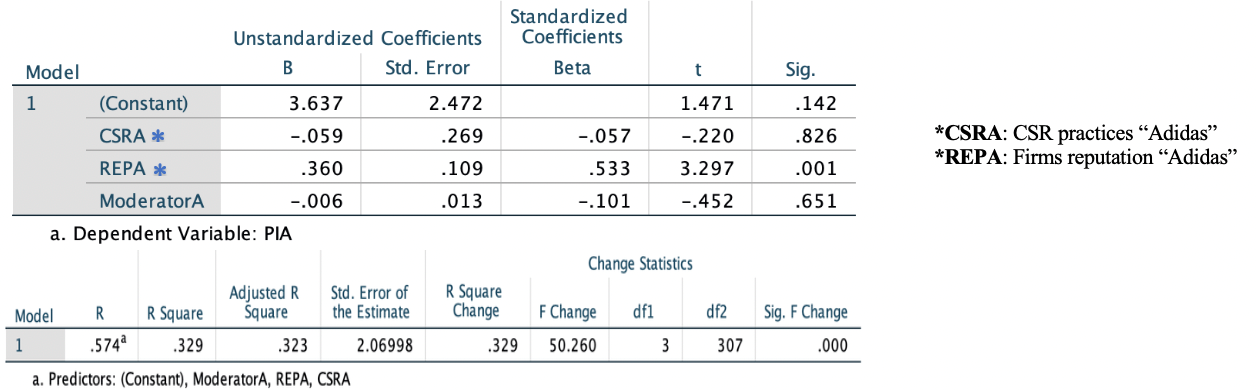

Lastly, hypothesis 8 examines whether skepticism towards CSR practices moderates the effect of corporate reputation on green purchase intention. To examine this, a moderator analysis with multiple regression is performed for both two companies. In Table 15, the results for Adidas show a significant model with p=0.000, R=0,574 and R-square=0,329.

Table 15 displays that the coefficient for the interaction term is not significant (β = -0.006, p = 0.651), which means that the effect of corporate reputation predicting green purchase intention does not significantly change at different levels of skepticism. These results show that a unit increase in the level of skepticism decreases the relationship between firms’ reputation and consumers’ green purchase intention of Adidas by 0.006. (Calculations in details can be found in table M, Appendix 5).

Table 15: Slopes of moderating effect of skepticism “Adidas”.

Comparatively, the results for Nike (Table 16) indicate that the regression model significant in predicting the moderating effect with p=0,000, R=0,551 and R-square=0,304. Table 16 shows CSR practices do not have a significant effect on the relationship between reputation and green purchase intention. Based on results from both companies, consumer skepticism towards CSR practices does not moderate the relationship between corporate reputation and green purchase intention, and thereby hypothesis 8 was rejected for both companies. (Calculations in details can be found in table N, Appendix 5).

Table 16: Slopes of moderating effect of skepticism “Nike”.

Remaining important results from the questionnaire

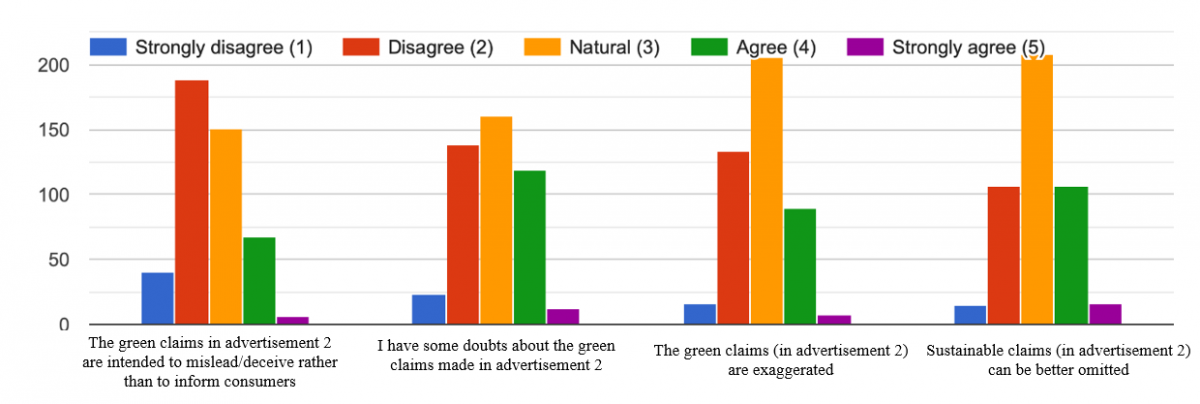

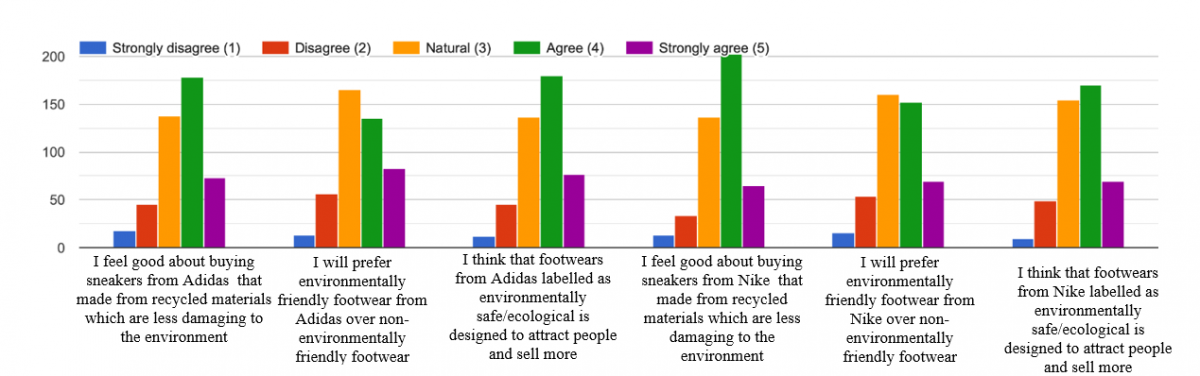

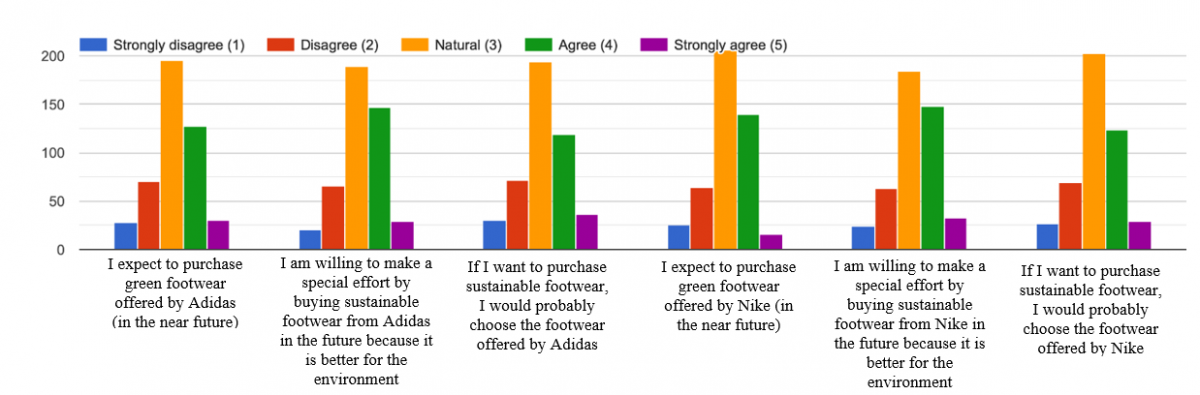

As can be seen in Appendix 8, outcomes of the questionnaire give an insight into the respondents’ opinions regarding the variables that were measured in this research. These variables are corporate reputation, CSR practices, consumers’ skepticism towards green advertising, CSR motives, green product, and green purchasing intention. A few remaining results from the questionnaire were discussed.

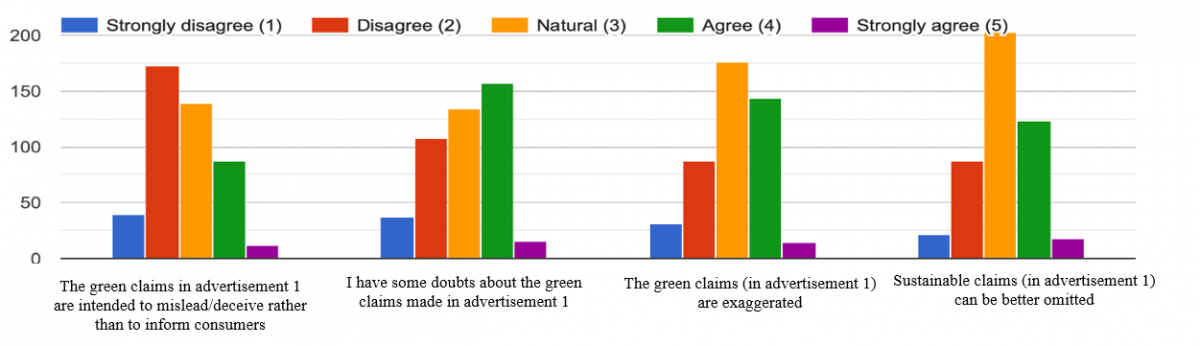

First, the outcomes of consumers’ skepticism towards green advertising show that most consumers think that green advertisements in Adidas need to be omitted or exaggerated. When it comes to the company Nike, most consumers think that green advertisements do not need to be omitted or exaggerated. Moreover, the majority of consumers have some doubts about the green claims made by Adidas. However, most of them are less doubtful when it comes to the green claims made by Nike because they do not think that both companies misled by these claims. Second, the outcomes of consumers’ skepticism towards green products show that consumers are not skeptical about green sneakers offered by both companies. Consumers have a favorable feeling about buying green sneakers.

However, most consumers perceive that both companies label their footwear as environmentally safe to attract people and increase sales. Third, the outcomes of skepticism towards CSR motives indicate that most consumers have neutral views by holding that both companies invest in CSR practices to get publicity. Finally, the outcomes of green purchase intention reveal that the majority of consumers would like to buy sustainable sneakers.

Discussion and further research

Reflection on results

After the analysis process, it appears that five of the eight hypotheses are supported for both Adidas and Nike. Table 17 provides a clear overview of all hypotheses in this study and whether they were supported or rejected

Table 17: Results of hypothesis testing.

First, to emphasize which variables do not show a relationship in this study, the rejected hypotheses were discussed. Hypothesis 2, for instance, there is no significant evidence that skepticism towards green advertising in both two companies has a negative effect on consumers’ green purchase intention. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was rejected in both Adidas and Nike. Hypothesis 5 was also rejected for both companies that skepticism towards green advertising has no significant positive effect on consumers’ negative WOM intention.