Abstract

The Middle East is one of the fastest growing economic regions in the world. Trade commissions from ‘first world’ countries are encouraging their nation’s businesses to seize the opportunities that exist in the Middle East’s low penetration rates and immature, but cash-rich, market. It can be argued, therefore, that the Middle East has ‘green field’ potential for eCommerce. Not all technologists are convinced of the viability of eCommerce within the Middle East. Writing about Dubai, for example, El-Kady (2005), stated that ‘online shopping in Dubai may never match the explosive success it has enjoyed in countries such as the United States’. Nonetheless, it is imperative that the trends of eCommerce are identified so that current and future eCommerce companies can draw on this information to their own commercial advantage.

The main objective of this study is to understand the enabling and inhibiting factors that influence the consumer adoption of eCommerce within Dubai, an Emirate within the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Dubai was chosen for this study due to its rapid expansion and development over the past ten years, making Dubai one of the pivotal commercial centres within the Middle East. In analysing the aforementioned factors, consideration were given to some of the broader theories and models that have been hypothesised about behavioural traits and constraints. These include the Diffusion of Innovation Theory (Rogers 1962), Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen and Fishbein 1975), Technology Acceptance Model, (Davis 1989) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (Venkatesh et al. 2003). It was anticipated that an application of these various theories and models will help provide a clearer and deeper understanding of the individual, societal and cultural influences that are specific to the world of eCommerce in Dubai.

It is important for academia, government and existing and potential eCommerce businesses to understand the effects that a number of factors could have on the successful consumer adoption of their product/solution within Dubai, before they can successfully affect their own relative adoption strategies.

Introduction

Background

The era of the Internet has bequeathed considerably more capabilities and challenges to the way that commercial organisations and governments transact business, both between themselves and with the end consumer. We now live in an age where practically anyone with a home computer and a product or service to sell has the ability to become a player on the international stage of electronic commerce or ‘eCommerce’. eCommerce can be described as the participation of governments, companies and/or individuals in business communication and transactions over the Internet via disparate computers networks.

This thesis focuses on Dubai, which is part of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), a federation of seven Emirates which was formed on December 2 1971. There are seven Emirates which make up the UAE; these are Abu Dhabi (the capital), Dubai, Sharjah, Ajman, Umm Al Qaiwain, Fujairah, and Ras Al Khaimah. Each individual Emirate is ruled by its own ruler who predominantly rules their Emirate with a majority of autonomy, despite there being a federal political system in place. The president of the UAE is chosen by the Federal Supreme Council, which is composed of the rulers of the seven Emirates. The current president of the UAE is His Highness Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan.

Al-Maktoum (2008) states that the UAE’s population reached 5.6 million in 2007, of which, the population of Dubai currently makes up approximately 1.45 million of which more than 85 percent are expatriates. According to the records of the Dubai Statistics Centre (2007), the population of increased to 1.422 million in 2006, an increase of nearly 300,000 people since the same reported period in 2005. Sengupta (2008) estimates that the population of Dubai increases by 24,333 people every month, or approximately 800 people daily. In terms of gender, the UAE Interact Statistics site (2007) states that 75.5 percent of Dubai’s population are male and 24.5 percent are female.

El-Kady (2005) states that ‘online shopping in Dubai may never match the explosive success it has enjoyed in countries such as the United States’. This statement was highlighted to the researcher when he lectured to MSc mature aged students at a university based in Dubai earlier this year. The MSc course major was ‘eCommerce’. After the lecture, the researcher asked how many of the students, who were all full-time workers, had used eCommerce services before. Out of a class of approximately thirty (30) students, only three had used eCommerce previously and only one more than twice. This led the researcher to ask the question, ‘who are the users of eCommerce within Dubai?’ The researcher believes that eCommerce and eBanking are strong within Dubai, but as this report will show, the trends surrounding eCommerce usage are quite distinct.

Statement of the Research Problem

Within North America and Europe it has been widely acknowledged that the growth of eCommerce has been significant and analysts estimate that eCommerce revenue will reach just over US$457 billion in 2008 and doubling to over US$920 billion by 2012 (‘Favier 2007’, ‘Mulpura et al. 2008’).

With certain elements of Dubai’s inhabitants portraying a ‘souq mentality’, where it is typically necessary for the consumer to adhere to a philosophy of “touch before you buy”, these individuals also have a tendency to associate commerce with a need to achieve some level of social stimulation which one received of bargaining down to the best price for the goods or services that one requires. This approach to shopping is possibly one of the inhibitors which is holding back the full potential of eCommerce (El-Kady 2005). According to Rahimi (2008) who stipulates that despite an estimated 20 percent a year growth rate in internet users to a current 33.5 million in the Middle East and that in 2007 eConsumers within the Middle East spent US1.5 billion on eCommerce products and services, but Middle Eastern eCommerce adoption trails that of Europe and North America.

This slow adoption of eCommerce can possibly be attributed to two main derailment factors, these being:

- The stage of social and economic development within the region, encompassing the classification of this developing society;

- The impact of Internet security issues that have plagued the Middle East for the past several years.

When an eCommerce enterprise is looking towards Dubai to enhance their market share, it is important for their business strategy to take into account that communications and thought processes differ from region to region, country to country, and culture to culture. A prime example within Middle Eastern culture is when considerable negotiation takes place leading into the ‘settlement’, signified by shaking hands (Hofstede 1991). Yet, in the Middle East the shaking of hands does not actually signify the end of negotiations but, in reality, identifies that the negotiations have just become more serious in nature and the real negotiation has just been set in motion. Hofstede (1994) further summerises a number of recognisable cultural traits that could quite easily be applied to the current societal attitudes in Dubai. These include:

- ‘Collectivist culture’ – which can be described as a tight social framework where loyalty is given to the clan, relatives and organisations. This is further reflected within the decision making processes; organisational structure and business conduct that is built on a perceived trust basis;

- ‘Power distance’ – where society accepts the fact that power within institutions and organisations is distributed unequally;

- ‘Uncertainty avoidance’ – which is when the society excepts and demonstrates strong characteristics such as aggressive behaviour, the showing of emotions is permissible; a strong belief is placed in the knowledge of recognised experts; and ordinary citizens are perceived as incompetent compared with the authorities.

Many researchers have also argued about the important influences of cultural shifts from one ‘age’ of society to another. These theories also resonate in Dubai. Reigeluth and Garfunkle (1994), for example, classified societal development into three ages – ‘the agrarian age, industrial age, and the information age’. Table 1 provides a simple outline of the differentiation between these three ages.

Table 1 – Major Paradigm Shifts in Society

The business environment in the Middle East is heavily influenced by ‘Sharia’ or Islamic law. Read (2004) stated that Sharia is the building block that governs both the public and private lives of those living within an Islamic community, and governs many aspects of day-to-day life: politics, economics, banking, business law, contract law, and social issues. However, despite being an Islamic country, the culture of Dubai reflects an apparently more liberal lifestyle than other Middle Eastern countries. From an outsider’s point of view Dubai seems to be considerably westernised. Nonetheless, there is still a tendency for nationals to portray traits similar to those found in a fatalistic and masculine dominated society, described by Kluckholn and Strodtbeck (1961) as a ‘subjugation culture’, that is a society whose attitudes are typically accepting and where life is seen primarily as pre-ordained.

Today’s Middle Eastern business temperament and landscape has been shaped and defined by several catalytic events. Oil exploration within the region has obviously been the primary catalyst for fast-tracking society from an agricultural society (agrarian age) to an industrially focused society (industrial age). The discovery of the Dubai oil reserves in 1965 prompted the frantic rush towards modernisation and country wide infrastructure development programs. These programs were prominent between the mid 1960s and early 1970s, stalling in the late 1970s until the mid 1980s. This was mainly due to the collapsing of the commodity and oil prices.

The first Gulf War in 1991 caused oil prices to increase substantially, just as Dubai realised that they had only thirty five to forty years of oil reserves remaining. This revelation lead to His Highness Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, UAE Vice President, Prime Minister and Ruler of Dubai, to embark on the rapid modernisation of Dubai (Al-Maktoum 2008). HH Sheik Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum is determined to establish and build other successful pillars of industry such as tourism, technology, logistics and financial services. Based upon Reigeluth’s model, shown in Table 1, it appears that several countries within the Middle East are moving from the agrarian age, fast tracking through the industrial age, directly to the information age and, like Dubai, strive to become knowledge and technology based economies.

Although important, the cultural aspect surrounding the acceptance of eCommerce within the Middle East and, in particular, Dubai is not the only factor that has the potential to adversely affect the consumer adoption of eCommerce. Another important factor is the user’s perception of the level of security surrounding eCommerce and, more pointedly, the security of personal information. Internet security is an important enabler for the consumer adoption of eCommerce. Bank fraud is growing at an enormous rate. In the context of the United States, as reported recently:

‘Nearly 2 million Americans have had their checking accounts raided by criminals in the past 12 months, according to a soon-to-be released questionnaire by market research group Gartner. Consumers reported an average loss per incident of $1,200, pushing total losses higher than $2 billion for the year (Sullivan 2004 )’.

One of the most recent security phenomena increasing the propensity of eBanking fraud is ‘phishing’. Phishing can be described as a fraudulent act in which the potential hacker sends an email to an consumer with the representation that the email originated from a legitimate establishment, such as a bank. The objective of the hacker, however, is to gather personal information from the consumer with the intention of using it for fraudulent purposes. A phishing attack can only succeed if the user clicks on the supplied URL and updates their personal and banking details as instructed. One of the reasons why phishing has been so successful is that the user will see that the site they have been redirected to ‘looks and feels’ like their normal eBanking site, but in reality this site is a facsimile. This is achieved by the hacker interchanging letters from a different character set for the legitimate character in the site name.

Although phishing is seemingly a recent occurrence in eBanking, it has already reached disquieting proportions. Litan (2005) stated that by June 2004 phishing and identity theft had already exceeded an estimated US$2 billion, with the finance industry becoming anxious that this could be just the tip of the iceberg. This has been proven with new statistics recently published by McCall (2007), an analyist from Gartner Inc, where he states that phishing attacks in North America have escelated exponentially in 2007 being estimated as high as $3.2 billion. McCall (2007) also found that approximately 3.6 million North American adults lost money in phishing schemes in the 12 months ending in 2007, as compared with the 2.3 million who did so during the same period in 2006.

‘Dubai is not immune to cyber crime’, as reported by Kaul (2003:np), ‘in the UAE alone, hacking in the first six months of 2003 grew 300 percent over the last six months of 2002. Just one hacking incident of ATM fraud, caused the UAE to lose between US$2 billion and US$3 billion’. Although the percentage of actual hacking attacks have been considerably lower than the rest of the world, the profile, complexity and sheer fiscal loss within Dubai has been severe. This has given Dubai and the Middle East a reputation of lacking the necessary regulatory controls within its financial services industry to abate such crime, particularly when compared to the financial controls and legislation implemented within the past five years throughout Europe and North America. This is evident when trying to use a credit card issued from a ‘non-approved’ country, such as Dubai. The credit card often fails to qualify under the latest stringent standards imposed from online financial institutes such as PayPal.

Very little is known about the actual amount of computer crime that has been perpetrated to date. Thibodeau (2001:np) stated that, ‘Government officials in North America estimate that only 20 percent of computer crime incidents are being reported because the agencies either don’t have the technical sophistication to discover the crimes or they want to keep bad news quiet’. Thibodeau also states that ‘this attitude is destined to change in the near future, especially with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the Office of the Controller of the Currency, and the Office of Thrift Supervision’s recent interpretation of the Graham-Leach-Bliley Act’. Governments and regulatory boards will start to pressure the banking and finance industry to be more forthright about its ‘cyber and personal data infractions’.

TechWeb News (2005) reported that the aforementioned US government agencies informed the banks that they it was mandatory to implement a response program which would warn eConsumers of potential issues when information has been accessed inappropriately and that this access could result in substantial harm or inconvenience to the customer. The consequences of this landmark interpretation are bound to have a substantial impact on the way the banking and finance sector looks at both its internal and external data policies and IT security.

From an individual perspective, not everyone who uses the Internet is security conscious. The vast majority of Internet users may not even have a firewall implemented within their home or work IT environment. It is therefore understandable why security could be a major hurdle for potential Dubai eConsumers engaging in eCommerce.

The Purpose of this Study

This study was undertaken to obtain a greater understanding of the enablers and inhibitors needed to create a model that would outline eCommerce adoption within Dubai. Although there has been considerable literature published which investigates the adoption of technology within various societies there has been little literature that identifies the adoption of technology within a society rapidly moving from one social order to another, as is currently being experienced by Dubai.

Sampler and Eigner (2003) indicate that Dubai, in the early 1960’s, showed traits of being an Agrarian society, some of these traits are identified within Table 1Table 1; where in 2005 the ruling government to acknowledge that they are now striving to have Dubai become a information age based society. (Al-Maktoum 2005). Although there have been various studies which identify technicality adoption trends within the developing world such as ‘Chong, 2006’, ‘Davis, 1989’, ‘Nguyen and Johanson, 2008’, ‘Smith et al, 2008’, ‘Venkatesh, Morris, Davis, Davis, 2003’ there have been limited studies completed on such a rapidly changing society such as Dubai.

This project strived to create a model which would outline eCommerce adoption within Dubai.

To be able to develop this model various government organisations, business and tertiary educational establishments were targeted in the investigative phase of this study. These organisations were chosen due to their predisposition in allowing researchers to approach their employees, students or membership, through authorised channels for the purpose of research.

The structure of this report

This report has been logically structured to take the reader on a journey of discovery. It has been divided into seven distinct components, as follows:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Theoretical model

- Research methodology

- eCommerce analysis within Dubai

- Evaluation

- Conclusions and observations

It is the intention of the researcher to provide a solid grounding in relation to the history and trends of eCommerce and eBanking worldwide. This will ensure that the trends surrounding eCommerce adoption within Dubai, which are been identified within the section 2 – ‘Literature review’, can be benchmarked correctly.

Literature Review

The new age economy incorporates both traditional ‘bricks and mortar’ firms and ‘e’ firms built on Information and Communication Technology (ICT). ICT also serves as the bridge or the gateway that enables the traditional and the ‘e’ economies to interoperate effectively. Within this new economy, there is a diffusion of norms, cultures and the manner in which business is conducted in the new age. While in some cultures a handshake between business associates still seals a deal, it now needs to be supported and augmented by a massive exchange of information. This can only be enabled by an effective ICT strategy. But, ICT cannot exist on its own; it must serve and be accepted by people and business. The business community of Dubai seems to have realised the enormous potential that ICT offers as a means to build strategic networks across Africa, Asia, the Arab world and India.

An ICT infrastructure cannot grow overnight and it cannot be transplanted and forced into a culture that is unwilling or unable to accept it. In today’s modern society we speak of a clash of concepts rather than a clash of culture. The ever widening digital divide continues to separate the ‘haves’ from the ‘have nots’ of the world. What is required for ICT to grow and flourish, within both developed and developing countries, is awareness. If a nation is to rise up the “needs hierarchy”, as identified by Maslow, it must have sufficient support by the government and most important, a population that is ready to embrace technology. eServices is a manifestation of ICT along with Business to Business – B2B and Internet Banking and so on. It touches housewives, students, professionals as well as businesses and it gets personal with peoples’ lives, touching them in more ways than one. As an example, while B2B would allow a company such as Wal-Mart to source its products from South America through the supply chain and distribute it in Dubai, it would be eCommerce that would help a person sitting at home to browse thousands of items, select the required one, order it and pay for it. One of the most important facts of eCommerce is the ability to level the playing field between multi-national companies and the local corner store. eCommerce provides the opportunity for unprecedented access to markets never before seen in history. For the sake of this study all forms of eCommerce will be referred to as eServices.

Table 2. Types of eServices

For eCommerce to develop, take root and have a large penetration base of adopters, a stable and viable economy is required, plus the right cultural traits and the right cultural norms to allow new and emerging technology to be adopted. This chapter outlines an extensive review of these areas and also reviews the perspective of global eServices and the existing eServices in Dubai. The main goals of the chapter are to assess the economy and culture of Dubai; understand different models of technology adoption in developing countries; and the extent of eServices available in Dubai.

Dubai – History, Demographics and State Profile

Dubai is one of the seven Emirates that form the United Arab Emirates (UAE). It is the largest Emirate of the seven.

Ancient Stone Age nomadic people settled in the mangrove swamps along the coastline where modern day Dubai is situated. The remains of their settlements have been dated to 7000 BC. Civilisations of Byzantine and Sassanian empires controlled the gulf areas and the people worshipped the god Bajir. After the Prophet Mohammed extended the teachings of Islam from Mecca, the people in the surrounding regions embraced Islam and the Caliph of Umayyad drove out the Sassanians and assumed control it. Around 1050 AD, Dubai was known for its pearl industry and this fact is mentioned by Abu Abdullah al-Bakri, the Arabic geographer of the 10th century. For many centuries, the city served as a port and centre of trade for the Arabic region because of its strategic location, sufficient backbays and calm waters. This allowed ships to be outfitted while they berthed. The state came under British control in 1892 and gradually developed to acquire importance in the region (UNISA, 2005).

With the discovery of oil in 1967, the state underwent astronomic changes in its economy and with the influx of petro dollars, the region became the centre of ‘geo-oil’ politics with all the Western nations developing a keen interest in helping the region to develop and exploit the oil resources. Unlike other petroleum economies, such as Nigeria or Venezuela where oil revenues have been squandered and a majority of the people live in poverty, Dubai and other Arab oil producing countries have a remarkable leadership with the great foresight to use oil revenues to develop their nations and invest in the future. The leaders of these regions have now begun to plan for the future, recognising that at some stage oil resources will be depleted. Plans have thus been implemented to generate revenues and employment through trade and financial investments (Dubai eGovernment, 2008).

While the UAE has based its GDP predominately on petroleum economies, Dubai has transformed itself into the commercial hub of the Middle Eastern region. It has moved out of the petroleum driven growth, into a business and investment centre. For the year ending 2005, Dubai had a GDP of 37 billion USD and there are plans to achieve a year on year growth of 11 percent to achieve an expediential growth of their GDP to 108 billion USD by 2015. The main revenue earners are from new pillars of industry. These include tourism, real estate, construction, financial services and re-export; while petroleum and natural gas will have contributed an estimate of less than 6 percent to the GDP (Reuters, 2007).

Demographics

By 2007 end, UAE had an estimated population of 4.48 million. With further economic developments the population is forecast to grow by 6.12 percent in 2008 and by 6.31 percent in 2009, to reach a figure of 5.06 million. Dubai had a population of 1.42 million as per the 2006 census and the number of females was 349,000 and males was 1,073,000 – a skewed ratio of 1:3 for women to men. The population is expected to rise to 1.59 million by 2009. The population is made up of 42.3 percent Indian; 17 percent Emirati; 13.3 percent Pakistani; 7.5 percent Bangladeshi; 9.1 percent Arab and 10.8 percent others. Islam is the official religion and Dubai is an Islamic state with all laws and legislation following the Islamic tenets. The state allows practice of other religious practices and building of places of worship, subject to some restrictions (Kawach, 2008).

Building the ICT sector in Dubai

The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) sector has greatly improved in Dubai and the government has invested heavily in the infrastructure to allow IT and Internet Technology Enabled Services -ITeS companies to evolve. While IT companies develop and market software products, ITeS companies provide help desk and support services using the Internet and software applications. Some of the areas that have been exclusively developed for promoting ICT includes Dubai Internet City – DIC, Dubai Media City – DMC, Knowledge Village – KV and Ras Al Khaimah IT Park. These are special free trade zones that are 100 percent tax free and allow 100 percent foreign ownership. ICT has a number of IT majors, such as Microsoft, Oracle, Cisco, and Siemens, with a total employee strength of 5500 and the plan to provide software development services, back office support to clients from Africa, India and the Arab nations. The infrastructure is very impressive but the city relies on foreign workers rather than Emirate citizens to run the operations. DMC offers media organisations to set up a base and offers facilities for different TV companies, Internet media services, online magazines and other forms of media (DIC, 2007).

Pohjola (2003) has pointed out that ICT is perceived as one of the important drivers of economic growth in developed and developing countries. Access or denial to ICT is often one of the main reasons for differences in revenues between countries. The author speaks of the digital divide or the information poverty that exists between countries and points out that early adopter often have a sustainable advantage over other countries.

When one considers that developing countries such as India have invested in IT at a very early stage and many Indian IT companies are regarded as some of the best IT companies in the world, Dubai would wish to develop similar competence in the IT related field.. The state has built all of the required infrastructure and many IT companies have set up offices in Dubai. ICT is gaining mass use.

The following table provides statistics on increase in use of different technologies in the UAE.

Table 3. Technology Adoption in UAE

As seen in the above table, the number of subscribers for Internet, dial-up Internet and Broadband internet has risen by almost 80 percent in 2006 when compared with 2005.

According to Pohjola (Pohjola, 2003), developing countries typically spend about 7.1 percent of the GDP on ICT infrastructure. The breakup is IT hardware 1.1 percent; Office equipment 0.1 percent; Software 0.5 percent, IT Services 0.9 percent; Internal Spending 0.9 percent; Total IT 3.6 percent, Telecommunication 3.7 percent and total ICT is 7.3 percent of the GDP. The figures do not speak of the expenses in construction, land costs, power and other cost heads. According to reports from World of Information Technology and Services Alliance- WITSA (WITSA, 2008), Dubai spent about 3.58 percent of the GDP on ICT in 2006. It is evident that there is a lot of potential for ICT growth in Dubai and consequently for eCommerce. ICT applications represent a huge market in Dubai. This may be one of the reasons for multinational IT companies to be investing in Dubai.

A more detailed review of ICT spending trends in Dubai is provided in Section 2.4.

Foreign investment

FDI in 2006 has shown an increase of 13.4 percent over 2005 and while in 2005, it was 37.4 billion Dirhams, FDI in 2006 was 42 billion Dirhams. FDI has been made in various sectors such as mining and manufacturing. The following table provides statistics about sectors in which FDI has increased or decreased.

Table 4. Dubai FDI Inflows in million AED

As seen in Table 6, the largest percent rise in FDI was in the Hotels and Restaurant sector, with a FDI of 38 million Dirhams in 2006. However, the Financial Intermediation & Insurance sector had the largest value of 15,025 million Dirhams, while the construction sector had a FDI of 14,652 million Dirhams. The Manufacturing sector has shown an increase of 43.9 percent with a FDI of 1,061 million Dirhams. The table indicates that foreign investors have gained sufficient confidence to increase investment in Dubai.

Table 6. Origin of FDI in million AED

The above table shows that countries from Europe have provided the largest FDI of 19,047 million Dirhams with non-Arab Asia Countries investing 17,569 million Dirhams. North and South America invested 3,034 million Dirhams, representing a decrease of 29 percent over the 2005 values. Arab countries have invested 565 million Dirhams, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries 1,208 and Oceania investing 911 million Dirhams.

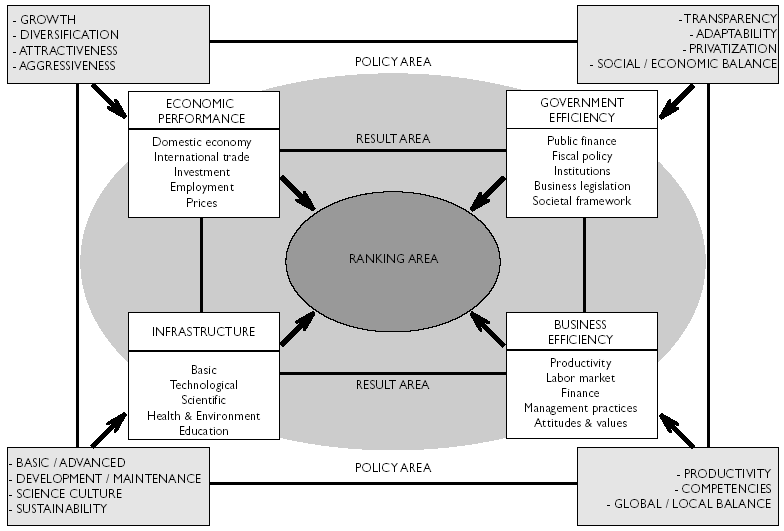

The Competitiveness Policy Framework is illustrated in Figure 1. Competitiveness Policy Framework. The framework is used to asses the competitiveness of a country by comparing key indicators with other countries. Specifically it would indicate where a country stands with reference to other countries in the areas of investor friendly government policies, infrastructure, economic performance and business efficiency.

“According to the Internatonal Media Dubai IMDreport of 2005 ‘”The central ‘Ranking Area’ depicts the consolidated rankings of Dubai in World Competitiveness while the ‘Result Area’ indicates the four “chapters of competitiveness” that explain these rankings and they are Economic Performance, Government Efficiency, Business Efficiency and Infrastructure. Each chapter has a number of individual criteria, which are ranked and consolidated into 5 sub-factors”. Dubai ranks 17 in the competiveness among other countries while USA has the first rank, Hong Kong 2nd, India 40th and Venezuela 60th rank. With a rank at 17th, Dubai is certainly successful at attracting FDIs and this trend is expected to continue (IMD, 2005).

Broadening the economic base

The government of Dubai is planning for the future by expanding the economic base and entering into other areas of trade and commerce. It is prepared for the fact that hydrocarbon reserves will be depleted in a few decades. UAE and Dubai governments have entered into eight bilateral trade agreements with the GCC and the European Union (EU) to expand trade in products other than hydrocarbons. There are plans to remove trade barriers. While in the earlier era trade agreements covered goods and products, the current agreements would also include investment and services and investment by GCC. There are efforts to increase the economic base by expanding into areas such as trading, investment, financial services, telecommunication and tourism. Though Dubai and UAE have industries such as Aluminium smelting, they are manned mainly by high wage foreign workers and it remains to be seen to what extent Dubai can be cost competitive with low wage countries such as China. One of the main advantages that Dubai can obtain is that it can invest in other countries and this is one way to ensure that the oil revenues appreciate (Franco, 2007).

Dubai actually represents a very huge market for items such as food, seafood, automobiles and automobile parts, cement, apparel, toys, dairy products, meat and poultry. The state imported about 89 billion USD of goods in 2006 while exporting non oil goods worth 137 billion USD. While these figure may appear very attractive, the fact is that most of the exports are termed as ‘Re-Exports’ where Dubai imports products and then re-exports them to other countries, mostly other states of UAE. The profit margin is much less in such ventures. It would be very probable that in the future, other Arab states may decide to import items directly from the countries of origins, at lesser costs and this would place Dubai in a huge trade deficit (HKTDC, 2007). So the very nature of trade is under scrutiny and this needs to be examined very closely as to how long it can be sustained.

UAE and Dubai has immense oil revenues but as of March 2008, the foreign exchange reserves are about 296.20 billion USD and in terms of Forex reserves, UAE is ranked 40 in the world. China, ranked 1st in the world, has 7.52 billion USD and India has 3.13 billion USD and is ranked 4th (SWF, 2008). Given this, the government of Dubai is not well placed to squander Forex reserves.

Perhaps, in foresight, money managers in the government have decided to invite foreign participation by providing lavish world class infrastructure and facilities in the form of construction, housing, public infrastructure and in ICT. Dubai has also developed infrastructure such as the Dubai Industrial City – DIC where foreign companies would be setting up industrial units. The government should encourage companies to use these facilities to either manufacture the items or import them as complete knock down kits (CKD) and assemble them for domestic consumption and also re-exports.

While it is expected that foreign companies would be investing in these free economic zones, the government should rethink its strategy of offering 100 percent tax exemption as the present economic model would become unviable in the future. Dubai uses a model in which the government spends huge sums of money to develop infrastructure, charges a nominal rent for lease of these properties or places rent control acts to prevent rents from rising, then extends 100 percent tax rebate to investing companies besides providing them with subsidised power and other utility. These companies hire foreign, low cost workers and then manufacture goods for export that are again free of customs duty.

Dubai Trade

Dubai as a trading hub takes up import, export and re-export of a wide variety of products. In 2006, Dubai imported products worth 59,910,428 USD, exports were valued at 4,975,057 USD and re-exports were valued at 21,337,583 USD. Please refer to ‘Table 2.1.5. Non Oil Dubai External Trade Statistics 2006’ that gives values in USD of import, export and re-export of different product categories for 2006.

Table 2.1.5. Non Oil Dubai External Trade Statistics 2006 in USD ‘000

As seen in Table 2.1.5., items such as maximum value of imports were machinery and mechanical appliances and natural or cultured pearls along with precious and semi precious metals and stones. There is a trade deficit between imports, exports and re-exports of the value of 33,597,788 thousand USD USD.

The table below provides details about the top twenty import country origins for 2006. These are the countries from which Dubai imports the most goods.

Table 2.1.6. Dubai top twenty Import Origins 2006

As seen in Table 2.1.6., Dubai imported the most items from China, India and USA.

The following table provides details of countries to which Dubai exported the most non-oil goods.

Table 2.1.7. Dubai top twenty Export Destinations 2006

New pillars of industry

In developing the new program for increasing the economic base, the government of Dubai has constructed many world class facilities and provided infrastructure regarded as ‘pillars of the industry’. These are designed to reinforce the image and message that UAE and Dubai are looking beyond crude oil and want to attract foreign investors. The next sections briefly discuss some key projects that have been developed. These pillars of the industry include ports, transportation, airports, Internet City, Free Trade Zones and others.

Ports

Dubai’s ports, such as Jebel Ali and Port Rashid, are designed to handle the large amount of cargo that is exported or imported. Dubai ports are affiliated to Dubai Ports World – DP World, a very large group that operates 45 terminals in the world and is a part of Dubai Holding. By interlinking the entire sister terminals, information access and sharing becomes very easy and delays in clearance and customs are avoided.

The Jebel Ali port is the largest man-made harbour in the world and it is the largest port in the Middle East. The port area is about 52 square miles and 67 large container ships can berth at the same time. With excellent loading and unloading facilities, the time spent at the docks for the ships to load or unload is very much reduced. What makes the port more important than just the massive harbour or the berthing facilities is the service it provides. This includes handling of container cargo, general and bulk cargo; a Roll On – Roll Off (Ro/Ro) facility with large parking lots for cars imported for local use or for re-export; livestock vessel berthing; reefer facilities; commercial trucking for on-road delivery of containers and other cargo; ferry and cruise terminals; a tanker facility for two multi-user berths for tankers and storage tanks for bunkering and storage of crude for transport; container repair; sea to air cargo facility; cold storage facility; long-term vessel lay-by facility for repair of ships or those waiting for cargo. In addition, the port is adequately supported by eServices. This offers a computerised system covering all aspects of shipping, such as booking, accessing the required forms, understanding the documentation required, knowing the status of the cargo and so on. This computerised facility reduces delays, brings efficiency and makes the whole process transparent. It removes the problems that importers and exporters face while sending their consignments.

Port Rashid is somewhat smaller and is linked to Port Jebel Ali and together they form the Dubai Ports Authority (Jebel Ali, 2008).

These two ports form the main pillars of Dubai trade and economy. Transport by sea is still the most cost efficient form for long distance logistics. By investing in these ports, the government has provided the means for exporters and importers and industries to send or bring in consignments. In many developing countries, ports are a big bottleneck and delays in the congested ports run into weeks. The two Dubai ports allow industries to build on the economies of scale so that the market prices can be maintained at the required level and costly delays are avoided.

Jebel Ali Free zone

The Jebel Ali Free Economic Zone (FEZ) is an area where foreign companies can operate with 100 percent equity holdings. Outside the free zone and in other areas of Dubai and UAE, companies have to enter into a 51:49 percent partnership with a local company that would hold the majority stake in the venture. But in the free zone areas, foreign companies can have 100 percent ownership and undertake any or all activities such as import of raw materials and goods, processing, re-export, re-manufacture or re-process, without having to pay any import or excise duty. Only standard criminal and civil laws of Dubai are applied to these companies and they are free to operate to the best of their means. Investments in the zone rose to 12 billion USD in 2007. (Jafza, 2008).

The main advantage of the free zone is that bureaucracy is reduced, as is the number of statutory rules and regulations to be followed. In addition, workers can be employed at very low cost. Manufacturing companies gain cost competitiveness when they import CKDs, assemble them in these zones and export the completed products to other markets. In addition, the companies are allowed to repatriate 100 percent of the profits or capital, with no minimum amount of investment and no restrictions on currency. Corporate and personal income tax is also not levied and goods can be directly exported from this region to other destinations. If the goods are sold into the local UAE market, then the standard import duties are levied. These free zones are provided with excellent support services, IT networks, infrastructure, utility and other features. Many US and Asian companies such as Sony, GM, Hyundai, Grundig, IBM, Samsung and other companies have set up huge plants and distribution warehouses. These companies use the free zones to assemble electronic devices and engineering goods and export them to Africa and parts of Asia (Jafza, 2008).

Advent of Free Zones

The free zones that have become a vital part of Dubai’s strategic plans seem to be based on the cluster theory, as suggested by Porter (1998). He defined clusters as “groups of interconnected firms, suppliers, related industries and specialized institutions in particular fields that are present in particular locations”. According to Porter, competitive advantage for a company is produced by the value that a firm is able to create for its buyer and this can be diagnosed through the supply value chain. He has further argued that innovation, improvement and change are critical in forming a competitive advantage by applying better methods to compete in an industry. Firms that operate in a cluster will manage to gain advantage over the national and international competitors if they can find new and better methods of production, building an economical supply chain, design, linking elements of the value chain and permit knowledge spill over. For industries in a cluster to thrive, they need to manage and administer the whole supply value chain made of vendors, buyers, suppliers, distribution and sales channels and the employees.

Kuah (2002), while prescribing to the cluster theory, points out that this theory is not new. Since biblical times, certain regions have carved a name for themselves. Citing examples of the ship building industry of Glasgow to the IT sector of Silicon Valley of US, steel instruments from Sheffield UK, the Indian IT industry and others, the author argues that certain regions became famous clusters because of the availability of natural resources or because the climate favoured growth of items such as tea, precious metals, crops and so on. But the fact remains that clusters enjoy a tremendous advantage in the form of a pool of skilled personnel, higher influx of technology, scale of economies and when managed properly, clusters do help a particular industry, community or group of people to grow.

With the present concept of global economy, Garelli (1997) suggests that that the ‘economy of globality and proximity would tend to be a major force in a market’. By being global, the production mechanisms can be situated in one continent and the end users in another and with improvements in communications and transportation, the world has become a global village and physical distance is no longer a barrier to international business relations. Multi-national corporations thrive on tapping international resources such as cheaper labour, raw material and location advantage for added competitive advantage.

It can be deducted from the above discussions that the key factors for a cluster to be successful are: enhanced supply chain, disbursing benefits to members in the community and a willingness to adopt new technology and ideas and to firmly believe in innovation. The most important element for a cluster to be successful is a sustainable supply chain. When these observations are considered, it is evident that free zones such as the Jebel Ali are promoting clusters and there is a rising concentration of industries such as textiles and apparel manufacturing, engineering goods, electronic items and other such products. By developing the free zones, Dubai is developing the strategic cluster theory and it is expected that in due course of time, sufficient mass would be developed in the area so that certain specialised set of services and product offerings would emerge

Dubai World Central

Dubai World Central (DWC) is the umbrella organisation that has planned a number of mega construction projects in Dubai. These projects are part of the new economic development plans that the government has initiated. They are forward-looking and visionary and are being planned in phases. There are currently six projects that are managed by DWC: Dubai World Central Residential City, Dubai World Central Logistics City, Dubai World Central Enterprise Park, Dubai World Central Commercial City, Dubai World Central International Airport and Dubai World Central Golf Resort. It is estimated that a total of about 125 billion USD is invested in these projects. In a region known for the lavish and grand construction, the six projects are designed to place Dubai as the preferred location for residents, professionals, trading businesses and various industries and service organisations (DWC, 2008).

Dubai World Central Residential City is a high profile and exclusive residential city that would will provide housing for the thousands of professionals who would be working in the different business areas. With 7.16 million square metre of real estate, more than 50,000 professionals could be housed in this area. In addition to modern amenities, the area will have extensive utilities, power, water supplies, schools, recreation, hospitals, shopping malls and other facilities (DWC, 2008).

Dubai World Central Logistics City is designed to provide supply chain logistics for the immense trade and business activities that evolve in Dubai and the free economic zones. The City will have modern office buildings and free hold plots for trading companies, industrial businesses, logistics service providers, distributors, and forwarders. It will also provide shared facilities, such as air-side cargo handling facilities, air to air or air to sea support along with warehouses for storing in transit goods. Air freight of 12 million tons per annum could be handled through the 22 air cargo terminals. There are plans to have a dedicated aviation area that would provide direct apron access. There are also plans to provide accommodation for 40,000 employees who would be working in the area (DWC, 2008).

Dubai World Central Enterprise Park is designed to provide a special environment for companies that would be using alternative products, advanced materials and special technologies. A modern university is also being planned for 4,000 students, who would be taught to link research and industrial applications (DWC, 2008).

Dubai World Central Commercial City is designed to be the financial hub for Dubai and about 130,000 people would be working in more than 850 skyscrapers and towers. There would also be luxury villas, very expensive homes, hotels, shopping malls and avenues for entertainment (DWC, 2008).

The Dubai World Central International Airport is planned to be the heart of the Dubai World Central projects and when completed, it would be the largest airport in the world in terms of cargo handling and passengers. The complex would serve as a transit point for Pan America and Asia travellers and also serve as the hub for the large amount of cargo that is expected in the future. When fully completed, it will be able to handle about 12 million tons of cargo. It will also have 6 parallel runways and will be able to handle the largest commercial aircrafts (DWC, 2008).

Something of an anomaly in a desert region, the Dubai World Central Golf Resort will have two 18-hole golf courses, complete with fully landscaped lawns and garden, high income residential buildings along the periphery, hotels and boutiques. The golf course will cater to the local demand and is also expected to be a part of the PGS tour in the future (DWC, 2008).

Air hub

Dubai has a high volume of trade and while the ports provide shipping for bulk products and engineering goods, the air ports provide a very vital link between the different business districts, consumers, organisations, shopping malls and other entities. (Dubai Airports, 2008).

The existing Dubai International Airport is the 6th largest aviation hub in the world and handles more cargo and passengers than the Changi International Airport of Singapore. In the first quarter of 2008, the airport saw 9.34 million passengers and more than 124 airlines from 207 destinations across the world use the airport. There are plans to achieve 40 million passengers by the end of 2008. Freight handled in the first quarter of 2008 was around 399,718 tons, a 10 percent increase over the same period in the previous year. In the future, this airport will serve as a feeder to the Dubai World Central International Airport, which is expected to be about 3 times the size of the current airport. (UAE Interact, 2008).

With the advent of low cost carriers that operate for relatively shorter distances, Dubai offers a central hub for transit passengers. To meet the requirements of such passengers, Dubai has been committed to providing them with the best in shopping and eating experiences. There are a number of duty free shops that offer branded products, available in the best boutiques around the world. The airport also serves as a cargo hub for transhipments to other Middle East countries and Africa, in which western aircraft do not have many routes.

Dubai Gold and Commodities Exchange

The Dubai Gold and Commodities Exchange (DGCX) was set up on November 22, 2005 and is a fully automated exchange that offers a market for online currency exchange and commodities. The exchange offers forward contracts on British Pounds, oil futures, gold, Euro, silver and Japanese Yen. Within a short span of four years, the exchange has made an impact on the financial centres of the world. With hectic trading in commodities, the centre recorded 930,000 futures contracts in the first quarter of 2008, worth about 48 billion USD. With stock markets crashing around the world, gold seems to be a safe haven for investors and Dubai, which has traditionally been an exporter of gold, has seen very high trading volumes (DGCX, 2008).

Dubai International Financial Exchange

The Dubai International Financial Exchange was set up on September 26, 2005 and lists Sukuk, equities, structured products, conventional bonds, derivatives and funds. The exchange is located in Dubai’s International Financial Centre and while the volume of trading is still low, the exchange will soon mature and serve as one of the major bourses of the world (DIFX, 2008).

Tourism

The hospitality industry and tourism in Dubai has experienced a growth of 22.78 percent in revenues and the 6.5 million guests contributed 10.83 billion Dirhams. With 40,862 hotel rooms and suites in 2006, Dubai was running out of hotels and there was a steady period of high occupancy rates of 75 percent. By 2012, the tourism industry is expected to increase to 11.2 million visitors and there is expected to be a 40 percent rise in the number of tourists who would be visiting various states of Dubai (DDTCM, 2008). As seen in the table below, hotel revenues have shown a rise in revenues of between 20 to 22 percent.

Table 2.1.7. Dubai Hotel Revenues Dirhams ‘000

Tourists in Dubai can sample the traditional as well as the modern delights that the city offers. Some of the buildings worth seeing include Al Fahidi Fort, H.E. Sheikh Saeed Al-Maktoum’s house , the Burj-al-Arab Hotel, Jumeirah Beach Hotel, Emirates Towers, World Trade Centre and many more exquisite buildings. Dubai waterfront areas include the beautiful beaches where facilities for jet skiing, snorkelling, swimming, scuba diving and surfing are available. There are also artificial islands such as the Map of the World and the Palms. Many visitors visit Dubai for the shopping experience and virtually all types of electronic goods, apparel, household and domestic appliances, luxury and life style items, carpets, textiles, gold and jewellery, traditional Arab handicrafts and other items are available. Dubai also offers the best cuisine and a very wide variety of dishes such as Western, continental, Chinese, Italian, Mexican and other types are available in the hundreds of hotels and restaurants. People come to Dubai to unwind, relax and usually have a good time (DDTCM, 2008).

Construction

Construction activity has picked up very well in Dubai. In 2004, construction contributed 13,977 million AED. Some world famous structures include the Burj Dubai tower that will cost about 4.1 billion USD and be the tallest man-made structure ever made with a height of 3000 feet. The construction is expected to be completed by 2009 and the lower level of floors is already fetching prices of about 43,000 USD per square metre. Construction sectors employ more than 50,000 people and the sector currently has projects worth more than 125 billion USD. Some other famous buildings are the Rotating Tower, The World Islands, Palm Islands, Dubai light rail transport and many other towers, buildings, housing societies, commercial and residential complexes (DDTCM, 2008).

Dubai wishes to show to the world that it has enough revenues and funds to take up such huge investments. These measures are taken to encourage foreign investors and workers who are expected to come in ever larger numbers.

Water, Power and Energy

Fresh drinking water has been a problem in UAE and Dubai and the government spends increasing amounts on desalination and water harvesting. Interestingly, Dubai has a good agricultural base and has achieved self-sufficiency by growing fruits and vegetables. But the government is asking itself if the vast quantity of water used for agriculture is really worth the expense. Sector-wise consumption of water in 2006 was Agriculture 58 percent, amenities 7 percent, industry 1.5 percent, domestic 15.5 percent and forestry 18 percent. The agriculture sector is heavily subsidised by the government and the number of private farms that have been established has increased by 26 percent. But the government insists that valuable fresh water can be used for other sources since the ground water level has reduced to an alarming extent. Drinking water will remain a constant challenge for Dubai.

Dubai consumed 24,756 gigawatts of power in 2007 and the yearly increase is 15 percent. Most of the energy is obtained by thermal power stations. The state is exploring alternate energy forms such as solar and wind turbines. With the massive growth planned for the future, Dubai will need to provide a large amount of power for the industrial zones and other areas that are planned for the future. This will present certain issues since thermal power stations would increase pollution and consuming diesel for power generation would prove expensive. UAE is exploring harnessing nuclear power to provide power for future needs but considering the dangerous nature of nuclear power and the geographical proximity of the zone to terrorist areas, the proposal would require intense lobbying (Zawya, 2008).

Business incubators

In addition to creating infrastructure for foreign investors, Dubai also has many programs to finance and develop small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Funds such as the Khalifa Fund are designed to help small entrepreneurs with zero interest finance up to 1 million AED and low interest loans for projects more than 1 million AED, subject to a maximum of 3 million AED. In addition to providing loans, the fund also provides training, business consultancy to the applicant. The funds are meant for nationals of the Emirates who may be fresh graduates or those who have worked for some time and wish to venture out on their own. These measures would also help to lessen the workforce in public sector units that are largely overstaffed.

About 115 SMEs have been financed by these schemes and the strategy is to develop a set of entrepreneurs who would one day be able to utilise the large infrastructure projects that are planned (UAE Interact (b), 2008).

Sports City

The Dubai Sports City is estimated to cost 4 billion USD and offers facilities for indoor and outdoor stadiums that would seat about 100,000 spectators. The complex is to help the Dubai government in its bid for the 2016 Olympics. The complex will offer a place for sports academies that would provide training, sports rehabilitation and accommodation for a variety of athletic and other sports such as cricket, football, basketball, golf, rugby, and hockey. The centre is built to conform to Olympic standards and has swimming pools, gymnasiums, tracks of different types and would also serve as a centre for large events. In addition, the area would also be provided with residential spaces, hotels, shopping malls and other venues for entertainment and shopping (DSC, 25 September 2008).

Leveraging key assets

The previous sections have extensively dealt with the infrastructure that Dubai has planned and is in the process of implementing. The activities would have to be analysed with reference to SWOT analysis and Porter’s National Diamond Model of the Competitive Advantage of Nations (Porter, 1990). Use of these tools provides a better analysis of the economic and business conditions and helps to bring the existing conditions to the fore.

Dubai SWOT Analysis

A top view analysis of the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) to Dubai in relation to the economy and business potential is given below. The objective of using the SWOT tool is to assess the competitive advantage of Dubai and to assist in understanding the potential for eCommerce. The observations are derived from the “Dubai in World Competitiveness 2005” repository and chapters used include ‘competitiveness policy framework for Dubai’ and ‘Dubai in world competitiveness’ (IMD, 2005).

The main points that have emerged from the SWOT analysis are that Dubai has excellent infrastructure for trade and investment and the GDP is expected to grow at 12 percent. However, there is a high import level that consumes earnings and there is a danger that, with a very high level of foreign workers who send their money home, the economy could slide deeper into the negative.

More detail relating to the SWOT analysis is provided below:

Strength

- Dubai has moved away from dependence on oil. Contributions to the GDP from other sectors are: services sector 65 percent, Industry 34 percent and agriculture 1 percent. Services sector include areas such as trading, transport, financial and non-financial services, real estate and business services, government services, construction, restaurants and hotels. The non-financial sector contributes 83.1 percent, financial 9.7 percent, the government and households’ sector 7.2 percent and construction 13 percent.

- There is a consistent GDP growth of 12 percent over the previous five years and GDP per capita is 28,125 USD. This indicates a stable and growing economy.

- Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) are increasing and, with 2 billion USD or 7.7 percent of the GDP, this indicate that foreign countries find Dubai attractive. Investor-friendly policies and lower corporate taxes have encouraged multinationals to set up offices.

- Tourism has increased and contributed 4.8 billion USD in 2004. A number of free trade zones and ports are available.

- Low unemployment rate of less than 1.7 percent.

Weakness

- Current Account Balance as a percentage of GDP has a deficit of 9.9 billion USD and the current account deficit is about 33 percent of the GDP. This is mainly because of the huge influx of foreign workers who send money back to their native countries.

- Balance of Trade deficit is 6.3 billion USD and this is 114 percent of the GDP. This is a very unhealthy situation as the country relies very heavily on imports and is subjected to global inflation with rising prices in local markets.

- Dubai still subscribes to the Islamic laws and in some areas, alcohol consumption is prohibited and women face restrictions in how they dress. This deters Western tourists.

- The government sector has a high number of local employees and is considered as inefficient. Steps to privatise these enterprises have been discussed

- Native Arabs have not earned a reputation for efficiency and innovation. The state depends mainly on foreign workers to manage business.

- There are no companies that manufacture cars or textile industries and only trading is done. There are no plants such as steel, cement and other infrastructure plants.

- Dubai is investing very heavily for the future. The large scale of construction and the Dubai World projects would cause a massive drain on the GDP. Its present growth model is based on future expectancies that may not be realised. If the future economy moves to another zone, such as China or even Africa, then Dubai would have thousands of square meters of deserted cities.

Opportunities

- Dubai is making use of its strategic location to serve as a hub for the Arab world. It can act as a gateway to the Arab world when the supply of oil is exhausted.

- Local population can be educated and trained to assume technical skills

Threats

- Dubai would face competition from other states such as Kuwait, Abu Dhabi and Sharjah.

- Other cities such as Tripoli are developing very fast and their countries have oil resources that are controlled by Western countries.

- The construction activity is funded by debt and trade and re exports of goods manufactured in other regions. Once these other regions and countries start exporting, re-export would hit barriers.

- With a high level of imports, the GDP would be increasingly used to feed the population and with earnings being sent outside by foreign workers, the cash reserves would one day go into the negative.

Porters Diamond Framework

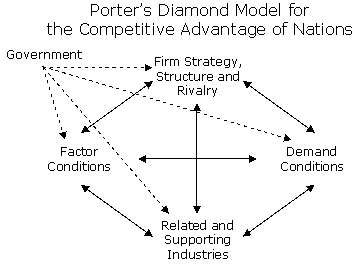

The framework attempts to analyse the competitive advantage of nations based on four factors, shown below, and would project the extent of competition that a nation can withstand when it enters the international market as a seller and producer of goods. The figure below illustrates the framework. According to Porter, understanding these factors would help Dubai to know where it stands in the world, who the competitors are and thee strategy that can be used to leverage its assets (Porter, 1990). The four factors are factor conditions, firm structure and rivalry, demand conditions and related and supporting industries. Please refer to Figure 2.1.2. Porter’s National Diamond Framework that illustrates the framework.

The framework is built on four main components and these are in turn driven by government policies. The four components are analysed as below.

Government: The Dubai government has adopted very pro-development policies with reference to promoting growth in the non oil sector. It has constructed many FEZ and introduced many schemes that reduce the tax burden and fixed costs for industries by providing them with incentives and tax concessions. So the score is positive in this factor.

Factor Conditions: Porter has pointed out that there are two factors, home grown resources and highly specialised resources. Home grown resources are items such as natural resources, raw materials and semi skilled resources and these can be acquired with the right amount of effort. Natural resources are globally acquired from developing or underdeveloped countries and some examples are minerals, crude oil, and timber. Availability of these resources in regions does not lead to competitive advantage as this factor can be replicated. As an example Japan is at the forefront of technology, yet it imports almost all its raw materials. The factor of highly specialised resources is important and this refers to the skilled labour, capital and infrastructure and intellectual property. While Dubai has ample capital, it lacks home grown or native talent. The skilled labour and intellectual property can be acquired by allowing an influx of foreign workers who would be willing to make Dubai their second home, provided the right kind of inducements were given. UAE has a long history of using foreign workers to run its infrastructure and industries but an issue remains in that much of those workers’ earnings do not remain in Dubai. This is an issue that Dubai has to accept in the short term. So the score is positive in this factor.

Related and Supporting industries: This factor refers to the setting up of clusters of supporting industry that act as feeder mechanisms for a mother industry. For example, an automobile manufacturing company such as Ford would require the support of hundreds of vendors and ancillaries. But with globalisation, this factor becomes diluted since components manufactured in one continent are assembled in a car plant in another country. But with the development of FEZs and structuring them according to the needs of the core industries, this factor can be accommodated. So the score is positive in this factor.

Firm Strategy, Structure and Rivalry: This is a very important factor when it comes to analysing Dubai. While the other factors analyse the strength of a nation with the market demands, this factor analyses the strength of the business rivals. Considering Dubai as a firm, its main rivals are China, Taiwan, Korea, India and other countries that use low cost labour to mass produce products such as textiles, apparel, small and big electronic items and other low cost-high volume products. If Dubai were allowed to be successful, the market share would essentially be derived from what these countries are producing. Given this, countries such as China and India would have to essentially remain stagnant and allow Dubai to eat into their business and market share. This does not seem likely. Moreover with imported and expensive labour, absence of natural resources, the cost factor would eventually become high for operators in the FEZ. Dubai presents a big market so the score is negative in this factor.

However, considering that the Dubai Government has set a mission to become the trading hub for the Middle East, the state has to leverage its key assets and prepare for the time when it would run out of oil revenues. The key assets of Dubai are its strategic geographic location that allows it access to the vast middle east and African markets, an experience in using skilled and unskilled foreign workers, a capacity to invest massive funds, backing of the powerful Arab community and the good will and positive image it has nurtured through the years.

The next section focuses on cultural traits of Dubai that encourage the growth of trade. It also analyses technology adoption theories and methodologies that explain the patterns of adoption in the developing world and the use of eServices across the globe. Finally, it analyses how eServices can be used in Dubai.

This next section provides an extensive review of cultural traits in Dubai and the UAE, and examines how that culture accepts change, new technology and the inhibitors and accelerators that exist for accepting change agents. The concept of systemic change along with a discussion on the movement and behaviour of social groups from the agrarian age to the industrial age and then to the information age has also been presented. Some case studies of how developing countries have fared with ICT adoption are discussed and the lessons learned from each case have been presented. Finally, a mapping of the lessons learned against Dubai’s development strategy is presented in order to assess Dubai’s readiness for adoption of ICT and other changes

Dubai Cultural Traits

Hofstede (2002) defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from others”. The psychologist argues that culture cannot be termed as the personal baggage of an individual but belongs to groups. In many countries, cultural boundaries often are the same as the geographical boundaries and people from a nation would be stereotyped by their culture. Walsham (2002) speaks of culture as a “dynamic entity that is all inclusive and it is impossible to freeze in order to analyse it”. Ho Chi Minh, the father of Vietnam had defined culture as “for survival and for the purpose of life, mankind created and invented languages, script, ethics, laws, science, religion, literature, art, daily tools for clothing, dwelling and made use of the. All of those creations and inventions constitute culture” (Pham, 2003). Culture is seen as something that a person is born with and carries until the end. It is culture that plays a very significant role in determining how a nation or a social group behaves. A forward-looking culture means one that the culture is ready to accept new challenges and opportunities along with the risk factors. A traditional culture means one that is more risk averse and not ready to accept changes.

Hosftead (1991, 1994), Jan Trompenaars (2002), Kluckhohn (1962) have published considerable works on culture and how traditional commerce has been instigated and engaged by culture. Kluckholn (1962) points out that there are three typical ages: Agrarian, Industrial and Knowledge. It could be argued that HH Sheik Mohammed wishes to take his country straight through to the information age in a far shorter time frame than was enjoyed by Europe or the USA.

Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions of UAE

Hofstede (2003) has created a framework to assess different natural cultures and the framework can be used to understand and predict the behaviour of cultures over a time period. The cultural framework has been used by industries and organisations over the world to understand how people from different cultures are expected to behave. Hofstede conducted research among a large number of IBM employees and the study covered about 70 countries. He identified five primary dimensions Power Distance – PDI, Masculinity – MAS, Individualism – IDV, Uncertainty Avoidance – UAI and Long-Term Orientation – LTO and each dimension was given an index value on a 1 to 100 scale. The indices can be used to assess and predict the national culture and behaviour, but not to assess an individual. A brief analysis of the dimensions and Hofstede’s scores are explained below.

Dubai has become a cosmopolitan city with about 80% of the population from other countries who form the workforce. Including these groups in the analysis would create disparity since people from India or UK would have different culture and a different rating for the indices., Only natural Arab citizens of UAE were considered for Hofstede’s analysis. This analysis is very important when creating a framework for the cultural aspects of Dubai and it would have an impact on the thesis objectives (Hofstede, 1991).

Power Distance Index – PDI

This index gives importance to the degree of inequality or equality among different strata of a nation. The index for UAE is 80 and the high value indicates that there is a high prevalence of inequality of wealth and power in the Emirates. The USA has a score of 40 (Hofstede, 2003). When the index is high then it means that there are various groupings in the country based on the caste system and wealth and power is distributed among a few elite. Upward mobility of the lower classes is hindered and strict laws, rules and a strict authority that specifies what is allowed and what is not, govern the society. Such societies have a leader who is prone to be isolated and distant. He would not be mixing with people, fearing that his image would be diluted. Dubai has a monarch that is the supreme leader of the state and his word is law. Consequently, the population obeys any declarations and edicts issued explicitly (Hofstede, 1994).

Individualism Index – IDV

This index gives importance to the relationship that is reinforced by society collectively or by individuals. The UAE has a low score of 38 while the USA has an index of 92. The UAE can be regarded as a collective society (Hofstede, 2003). In a collective society, the culture creates strong bonds among different classes of society and for people with IDV at 38, it means the word ‘us’, ‘we’ ‘our’ acquires more importance than ‘I’ and ‘mine’. Such cultures typically have joint and extended families that live together and unquestioning loyalty to the group is expected and given. The groups formed are very cohesive with strong bonds. There would be senior members in the household, such as grandparents, who would be regarded as honoured members and command a lot of discipline and obedience from the younger generation.

Collective society was the accepted way of life in all societies of the world from the ancient civilisations to the pre-modern world. Given the uncertainties of life in ancient times, people felt more comfortable with people of their own group who they could trust and with whom they could hunt, trade and live peacefully. This also gave rise to clans. Elderly members of a family with the knowledge gained from their long life were always around to offer worldly advice to their children and grand children (Hofstede, 1991).

But with industrial revolution, the societal norms were changed and in Britain and other countries, the young and the fit that could work in factories, left their villages and settled in the industrial towns. Theirs was a life of hardship with meagre food and un healthy living conditions. The old and the elderly were left in the villages and the settlements in cities were filled with nuclear families with single or two parents and their children (O’Brien, 1993). This is an important aspect when analysing the culture of Dubai where the UAE nationals did not have to go to other cities and countries in search of work. So, in effect, the nuclear family’s concept cannot be applied to Dubai as most citizens have lived their whole life in one of the Emirates with their parents and grandparents. As such, these people have very strong and traditional values and cultures and bindings to their social group, hence the low score of 38 for IDV (Hofstede, 1994).

Masculinity Index – MAS

This index focuses on the role and power of women in a society and how they are treated. UAE has a score of 52 while the average scores for all countries covered in the Hofstede ratings are 50 and the USA has a sore of 72 (Hofstede, 2003). This score can be interpreted as indicating that women in UAE share equal power with men. As such, the culture of Dubai is neither feminine (caring), or masculine (harsh) as traditionally, women have been regarded as more compassionate and caring than men. The analysis refers to the perception of women in society and while women may not be represented in positions of power in the government, the score indicates that there is not much gender differentiation. The conventional image, as depicted in the media, is that the Arab nations and the UAE dominate and subjugate women. The score of 52 indicates otherwise. As a corollary, the score indicates that women are not aggressive or eager to emulate men. The USA, where discrimination on grounds of gender, race or religion is not allowed, surprisingly has a score of 72. This indicates that gender differentiators are very strong and women increasingly aspire for positions of power in that society (Hofstede, 1991).

Uncertainty Avoidance Index – UAI

This index gives importance to the amount of tolerance that a society shows for ambiguity and uncertainty. The UAE had a score of 68 while the USA has a score of 46 (Hofstede, 2003). The index indicates that UAE culture does not like uncertainty in their life and there is a strong dislike for ambiguity. People from such cultures would feel more comfortable if they are subjected to rules, regulations and laws that specify what is acceptable and what is not. The score also shows that the culture and society has strong governance that ensures that the people have a steady and stable life. Such societies are not willing to change, avoids risks and there are inherent barriers to any new concepts of life and technology. Changes are regarded with trepidation. The low score of 46 for the USA indicates that their society is ready to accept changes and would undertake risks (Hofstede, 1994).

But there is a positive side when UAI is compared with PDI. The combination indicates that while UAE people are risk averse and not ready to accept changes and new technology, they are ready to accept rules and changes in technology if the government and the monarchy shows its support. This is exactly what is happening in Dubai as presented in Section 2.2, where the government has invested in the future by setting up FEZs, ICT infrastructure and other development projects (Hofstede, 1991). There is the question of foreign workers that have come to Dubai and these people have come with the main intention of earning high wages and making use of the opportunities that the government would provide/ They have come of their free will and it is expected that they will certainly adopt the new technology.

Joint analysis of the indices

When all the indices are considered together, it can be seen that UAE and Dubai has a collectivist culture that is separated by discrete social classes, is risk averse, avoids change and new technology, the people like to obey authority and rules and accept what the government says. There is a great dependence on the monarchy, which remains isolated and does not mix with the people and that has formed a controlled society. Barriers to adopting changes and technology exist but they would disappear if the government endorsed these changes.

Understanding Systemic Change