Introduction

Global commerce leads to agreement among nations; agreement is a byword of peace. In the 1990s when the Cold War ended and emerging economies opened up to world markets, there was economic prosperity in North America and many parts of the world. This is the significance of international marketing to world peace, in which national political borders are reduced leading to fusion of local economies.

Globalisation and technology have affected almost every aspect of human activity, whether this activity refers to individual or organisational endeavour. In the business environment, firms have to compete in multi-cultural markets which results in multiple marketing partnerships across national borders. Firms have to research on the different markets and adapt to changing environments prevalent in cross-border marketing.

Cross-border marketing is a term that refers to international marketing (IM). International marketing is a competitive strategy of global firms to expand their market to different countries and look for emerging markets that can provide more shares and profits for the company. Firms face many challenges in international marketing.

This study will provide an indepth analysis on international marketing, with a focus on the luxury goods industry.

An initial point of research is, ‘What constitutes luxury? Or, what is a luxury brand?’

The term tends to be subjective and the definition varies from person to person – or, from consumer to consumer. This is because what is luxury to one individual may not mean luxury to another. Phau and Prendergast (2000) argue that “… while one group perceives some brands as ‘luxury brands’, another group considers them as ‘major brands’” (p. 123).

In other words, there is no direct definition for luxury brand because it sometimes can be mistaken as major brand. However, a common knowledge is that popular brands are brands that live through time, survive economic crises and downturns, and people, the wealthy ones (the ‘rare’ ones), would like to exude them as status symbol because they are rare and expensive. A person who wears something rare must be ‘rare,’ too. A luxury brand is associated with price, social status, and exclusivity.

Vigneron and Johnson (cited in Phau and Prendergast, 2000) suggest the term prestige to weigh the element of luxury in a brand. The element of prestige that is intrinsic in a brand consists of noticeable and eye-catching pleasurable social value and ‘perceived quality value’. Brands that can be considered prestigious are categorised into ‘upmarket,’ ‘premium,’ and ‘luxury’ brands (Phau and Prendergast 2000). A luxury brand is considered at the extreme end of the three categories.

The elements that compose a brand that provide different uses are brand identity, awareness, noticeable quality and loyalty. Brands’ competition is based on the capacity to suggest elitism, provide a very popular identity or name, add brand awareness and perceived quality, and keep sales levels and consumers’ dedication and decision to purchase the next time (Phau & Prendergast 2000).

A brand is unique and rare so that if rarity is lost, it loses the luxury element at the same time. This is the ‘Rarity Principle’ espoused by Dubois and Paternault and Mason (cited in Phau & Prendergast, 2000). To retain this prestige quality in a brand, firms must sustain high levels of awareness and closely controlled brand ‘diffusion’ to develop exclusiveness.

Holt (2002) sees a branding environment in the near future in which brands will not simply fit and contain the culture of others, but should transform into cultural agents, producing quality important to consumers. Brands should be able to express a people’s culture. In Holt’s terminology, this is known as ‘expressive culture’.

Luxury brands that have survived through the harsh environment of the competitive world of business include Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Chanel, Calvin Klein, and other luxury products that include luxury hotels in Europe. All these will have available space for an indepth analysis in this study, including the reasons for their successes and situations surrounding the failure of some brands.

The research questions are: What constitutes luxury? How are luxury brands marketed? What strategies do they use amidst cultural challenges and other factors like political, economic, and social ones? Why do some brands succeed while others fail?

Aim and objectives

Aim

The aim of this dissertation is to conduct an indepth study of luxury brands, the strategies and campaigns they use to be successful in the industry and how they adapt to the prevailing culture in the host countries.

Objectives

- To conduct indepth analyses on luxury brands aimed at particular markets by geography, religion, or culture

- To conduct a qualitative study through review of the literature on the impact of culture on luxury brands’ marketing strategies

- To examine the relationship of international firms and how they build trust in cross border partnership

- To explore the factors in cross-border marketing, with a focus on cultural and religious adaptation

- To explore how luxury brands standardise or ‘glocalise’ as the prevailing culture demands

Rationale of the study

In order to increase their competitiveness, luxury brands need appropriate research and study on its relation with international marketing and branding in this time of intense globalisation and technology. Luxury firms have to continually adopt innovations and provide changes on their products and services. Firms have to understand the complexities of their trade, especially pertaining to customer information and the cultural milieu, so that the situation will not lead to more challenges and problems in their business and on the product they have introduced in the market. This study will fill the gap on the various environmental changes of international marketing, in particular the challenges of international luxury brands. We will delve on various aspects of globalisation and the popular brands that have stayed on course despite the challenges posed by economic crises and stiff competition along the way.

Literature Review

Introduction

In these times of globalisation, marketers are faced with increasingly multi-cultural marketplaces. Migration patterns and technological innovations require business organisations in international markets to operate in a multi-cultural setting (Luna & Gupta 2001).

Firms in emerging markets are now competing in international markets against larger resource-oriented and capital-intensive global companies. Many of these firms use aggressive marketing strategies, such as enhancing their products in the international scene amidst global competitors (Dawar & Frost, cited in Erdoğmuş, Bodur & Yilmaz, 2010).

Luxury brands are challenged with these new trends and business environment in the international market. The competition is between luxury brands against luxury brands, or luxury brands against major brands. Whichever is the ‘fighting’ environment, luxury brands have to apply new techniques and innovation to stay in the competition. This is the competitive world of business where the mighty and the strong survive.

While competition increases mass consumption of luxury goods also rises. This phenomenon (mass consumption) cannot be taken lightly due to the ‘rarity principle’ present in luxury goods. If mass consumption increases, the rarity principle is lost. Brands may have nowhere to go as they want an increase of sales but they have to deal with mass consumption. We will take the case of Louis Vuitton. The management had to reduce production in order to deal with mass consumption and restore the prestige and exclusivity of the brand Louis Vuitton. After all, Louis Vuitton is the brand of the wealthy class who exude in wearing luxury items, such as clothes, handbags, shoes, perfumes, jewellery, with uniqueness and prestige. Luxury consumers would say this is not for mass consumption. ‘This is for us, the elite!’

Emerging market firms come from different milieus and local business environments. They emerge from different local conditions, such as large and fast-growing markets like China, and other countries with uncertain political and economic environments.

Other firms already experienced in international marketing tend to regard new market growth as a strategic opportunity (Ansoff, cited in Akolaa, 2012), and consider international markets as the quickest way to expand. However, marketers understand that markets are different in terms of characteristics and behavior and that local and foreign markets are also distinct from each other. Marketers are able to distinguish the various cultural norms and factors and adapt their product to ‘cultural differences and similarities’ (Keegan, cited in Akolaa, 2012).

Cultures and brands

Cultural values play a key role in the entry of brands to international markets, so that when brands ignore cultural values, the firm encounters many problems along the way. This is known as ‘cultural bypassing’ (CB), which is primarily caused by the firm’s insufficient cultural research on the foreign market. Akolaa (2012) argues that the relation of culture and international marketing has not been given enough empirical research.

A concept of postmodernism led to the idea of ‘communal approaches to consumption’ where subcultures are formed. With the advent of the internet, the ‘global village’ emerged, with people hooked to the internet and wherein cultures and subcultures are formed. This is applicable to new concepts in marketing management, the ‘brand community concept’ where brand has to go beyond boundaries (Cova, Pace & Park 2007, p. 314).

One component of communal consumption (Kozinets, cited in Cova, Pace & Park) is the presence of several sub-tribes providing distinct meanings to a specific brand, and sometimes having as far as to compete with one another. The existence of several meanings and abundance of hidden conflicts is more made apparent by the presence of global brands that rally different groups with deep roots at a larger scale. Brand communities ignore the presence of borders (Muniz & O’Guinn, cited in Cova, Pace & Park, 2007, p. 314).

In managing brand communities, there are cultural and adaptation factors that have to be dealt with. Brand communities create oppositional brand loyalty or opposition to another brand; marketplace authenticity (which asks the question as to who is a legitimate purchaser of the brand); needed peculiarity (brand community members actually want the community limited or marginal) and the abandoned tribe (a brand community in which the marketer has left the brand for good, but the community still thrives, e.g., Apple’s Newton) (Cova, Pace & Park 2007, p. 315). A global brand is comprised of several local sub-tribes that are present in many parts of the world, telling us that they have different meanings, and communicate through the internet.

Cova, Pace and Park (2007) argue that in a global brand community sub-tribes exist in various territories. These sub-tribes provide common meanings assigned to the global brand and build up their own meanings of the global brand and, consequently, a specific local subculture. Meanings in different areas have a marketplace relevance that global marketers should take into account.

Luxury has natural attributes that are complex to its very being and compose of parts that speak more to obsession than reason (Okonkwo 2009, p. 304). Luxury includes originality and creativity in product and retail conceptualisation, that may include ‘craftsmanship and precision in creation and production; emotional appeal and an enhanced image in brand presentation; exclusivity and limit in access and high quality and premium pricing, all for a specific clientele’ (Okonkwo 2009, p. 304).

Impact of culture on brands

Any marketer, or any manager, knows that a brand has to adapt to the local culture. Culture affects marketing (Levitt 1986). Cultural differences affects the standardisation and adaptation decisions in marketing (Nakata & Sivakumar, cited in Ang & Massingham, 2007).

Culture impacts on ‘consumer ethical decision-making and behavior’ (Singhapakdi et al., cited in Swaidan, 2012), and affects the marketing mix elements. Studying the ethical directions of subcultures is important for marketing decision makers since cultural disparities affect ethical orientations and influence ‘product development, promotion, distribution, and pricing’ (Swaidan et al., cited in Swaidan, 2012, p. 204).

In this study of luxury brands, consumers form their own subculture, as followers and observers of the luxury brand. Subculture and national culture influence their decision making and their loyalty to the brand.

Culture heavily affects the way people see the world and that people’s views ultimately affect behavior (Manstead, cited in Ogden, Ogdean & Schau, 2004). Culture is distinct for all ethnic and non-ethnic groups. As Hofstede once said, it is ‘software of the mind’ (cited in Smith, 2010, p. 83).

Definitions of culture vary according to how scholars react to the culture they have studied. Culture refers to beliefs, morals and customs (Taylor, cited in Smith, 2010) passed down from one generation to another. Culture refers to clear and implied ‘living designs’ that exist at any given time and influence the ways people behave and act (Kluckhohn, cited in Smith, 2010, p. 85).

Another definition comes from Louise Damen (cited in Smith, 2010), which says that culture is ‘… learned and shared human patterns or models for living, day-to-day living patterns.’

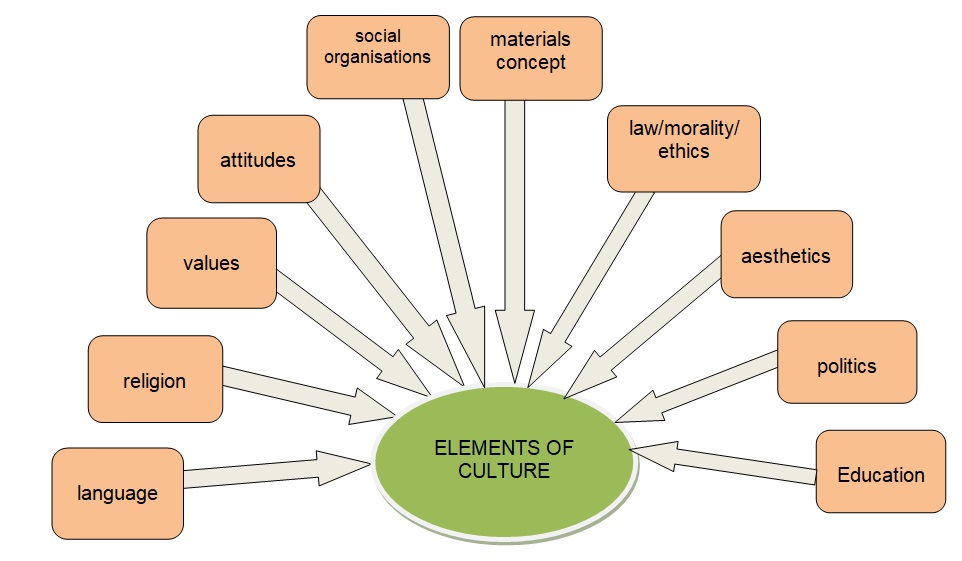

With many definitions of culture, scholars and academic researchers focus their attention on two approaches to understanding culture – Hall (1976) and Hofstede (cited in Smith, 2010). Hofstede’s definition is the most popular and widely cited approach to understanding culture. Lewis’ (cited in Smith, 2010) definition has also been used by international organisations and policy makers. Amidst these many definitions and explanations, it is commonly understood that culture refers to what people learned about ideas, values, and beliefs, which provide specific meanings (D’Andrade, cited in Smith, 2010). The meanings and interpretations are perceived to differentiate various cultures from one another over time (Hofstede, cited in Smith, 2010). Culture has several elements that influence the growth of an individual or the growth of an organisation. We can reflect on this in the demonstration of figure 1.

Through a comprehensive study of IBM employees, culture’s four dimensions (individualism, power distance, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity/femininity), made Hofstede (cited in Smith, 2010) the best source on the subject of culture. The four dimensions have been applied in cultural research across different areas, and used to explain aspects of leadership, management, and international marketing.

A hypothesis by Vitell et al. (cited in Swaidan, 2012) indicates that the four dimensions can affect understanding of consumer ethics across cultures. Related to this is Jackson’s (cited in Swaidan, p. 203) study which found that the cultural structure and content of ethical decisions of managers from countries like Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Poland, Russia, and USA, had cross-cultural distinctions for the managers’ ethical decisions, in terms of construct and content (Swaidan 2012).

Bridges, Florsheim and John (1996) studied how knowledge of a segment’s culture enhances a marketer’s promotional strategies. The authors investigated the impact of cultural characteristics on consumer preferences through service adoption, advertising and promotional activities. They explored the impact of culture as a way of determining customers’ preferences both at country level and individual level. The authors noted that consumers in various cultural orientations differ in their inclination to adopt or purchase products or services.

Cultural characteristics are affected by economic factors (Green et al.; Sethi, cited in Bridges, Florsheim & John, 1996), customers’ lifestyle (Douglas & Urban; Green & Langeard, cited in Bridges, Florsheim & John, p. 267), religion (Lee & Green, cited in Bridges, Florsheim & John), and education (Sethi, cited in Bridges, Florsheim & John).

The presence of simulated borders and of multiculturalism proposes that consumer needs and characteristics are distinct from each other even within national markets (Cavusgil & Nevin; Goldsimith & Vojnic; wind & Douglas; Wind & Perlmutter, cited in Bridges, Florsheim & John, 1996).

Studies tested the level to which response to promotional activities relies upon demographic factors, including their geographic residences whether urban or rural, ethnic preferences, religion and education. The researchers noted differences in how respondents could recall promotional gimmicks by service adopters using demographic symbols of culture. They identified similar relationships between demographic factors and promotional methods found to be effective (Bridges, Florsheim & John 1996).

The authors hypothesised that ‘a diverse national population, which includes a variety of locally accepted ethnicities and religious beliefs, is more likely to adopt a modern health care service (as opposed to traditional or tribal medical services) than either a rural or a homogeneous group, because of greater exposure to cultures outside of a single traditional society’ (Bridges, Florsheim & John 1996, p. 270).

High ethnic diversity can be found in countries like Nepal, Trinidad, and Kenya, whereas Hong Kong, Trinidad, and Kenya show high religious variation. There is not much ethnicity in Hong Kong and Jordan, and also not much religious diversity in Guatemala and Jordan.

The researchers (Bridges et al. 1996) investigated promotional methods and the impact of national cultural characteristics, and measured demographic indicators. There were six promotional methods applied in the focused cultures. These included activities for mass media advertising in radio, television, and newspaper formats. They also distributed short reading materials in clinics and installed flyers in store windows.

Bridges and colleagues’ (1996) study evaluated the use of advertising and promotional activities in multi-cultural environments, in particular by using aided recall, both at the country level and at the individual level or cultural groups within each country. Their findings at the country level showed that advertising and other promotional processes heavily relied on ‘country characteristics including population density, growth rate, literacy rate, and religious and ethnic diversity’ (Bridges, Florsheim & John 1996, p. 283).

Cultural societies having less rapid population growth rates, increased population densities, higher literacy rates, and more religious/ethnic diversities exhibit higher aided recall of promotional strategies of firms.

Impact of culture on buying behavior

Hofstede (cited in Smith, 2010) defines organisational culture as a concept that becomes apparent in an organisation because of the organisation’s location within a particular society. Many scholars have focused on the individualism /collectivism dimension (I/C) because this emphasises ‘fundamental differences in consumer behaviour between eastern and western cultures’ (Hoare & Butcher 2008, p. 157).

From Hofstede’s research, an argument reached is that countries differ significantly in their ‘score’ on the four dimensions. Hofstede’s researched has been recognised ‘to have been based on a rigorous research design, systematic data collection and a coherent theory to explain national variations’ (Sondergaard, cited in Garg & Ma, 2005, p. 261).

Cultural frameworks within people’s environments influence consumer buying behavior (Willer, cited in Al-Hyari, Alnsour & Al-Weshah, 2012). Religious beliefs also greatly influence buying behavior. For instance, there are countries and organisations which prohibit ‘the wearing of religious symbols’ (Crumley, cited in the Al-Hyari, Alnsour & Al-Weshah, p. 156).

Muslims around the world were once urged to boycott Danish products due to religious disagreements when a Danish newspaper published some caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed. Another perceived offensive move is the portrayal of the prophet and Muslims as terrorists (Knight et al., cited in Al-Hyari, Alnsour & Al-Weshah, p. 156).

Some scholars argue that there is a relation between cultural values and consumer behaviour, although this relation is regarded as indirect. In the case of Eastern countries, studies found that there is a model of ‘the influence of cultural values directly on attitudes, behavioural intentions’ (Lee; Chung & Pysarchik, cited in Hoare & Butcher, 2008, p. 157) and satisfaction (Leung et al., cited in Hoare & Butcher, p. 157).

Corporate culture, in difference to national culture, has been known to be the organisation’s ‘invisible strategic asset,’ but other authors argue that it is a liability (Flamholtz & Randle 2011, p. 21). Some brand stalwarts, like Howard Schultz of Starbucks, recognise organisational culture as a primary reason for their success, rather than the coffee. Southwest Airlines management also argue that their corporate culture is the primary ingredient for their success and their basic shield in economic crises. Google has been successful because it transformed a pool of talented engineers into an effective team, and has drawn more talents to the organisation due to its corporate culture (Lashinsky, cited in Flamholtz & Randle, 2011). Walmart’s corporate culture provides ‘organizational health and performance’ (Siehl & Martin, cited in Flamholtz & Randle, p. 22).

Standardisation or glocalisation

Standardisation and customisation are used interchangeably by scholars and researchers. Adaptation is the opposite of standardisation. Adaptation refers to localisation of products from the international market to the local market (Medina & Duffy 1998). Current research suggests ‘glocalisation,’ in which products or services are suited to the local markets but the international characteristics of the products or services are retained by the international firm or marketer.

Adaptation is defined as: ‘The mandatory modification of domestic target market-dictated product standards – tangible and/or intangible attributes – as to make the product suitable to foreign environmental conditions’ (Medina & Duffy 1998, p. 6). The marketer has to change its corporate structure model to one which is more consistent with the changes required in the new environment.

Customisation was first introduced by Terpstra (cited in Medina & Duffy, 1998), who argued that product ‘appropriateness’ is essential because many developing economies were beneficiaries of technology and product innovations from developed economies. Common economic disparities between developed and developing countries result in product offering from affluent markets and not appropriate for developing economies. Therefore, pronounced differences in beliefs and traditions, or culture, affect the purchase or acceptance of products (Samli et al., cited in Medina & Duffy, 1998).

Porter (1986) and other authors discussed customisation, but did not clearly define the term. Similar terms for customisation include ‘individualism’ and ‘specificity’. American Management Association (AMA, cited in Medina & Duffy, 1998) defined customisation as, ‘Tailoring the product to the special and unique needs of the customer’ (p. 7).

Luxury goods and brands

The world of luxury is actually for women. Well, this is figurative as we perceive that women love luxury and many of them would argue that they always feel their womanhood when they are luxurious. Advertising and commercials in magazines, journals and everything about luxury goods picture women in the world of luxury. This is not to say that men lag behind when it comes to luxury. There can be more men who love luxury than women.

This section will talk about luxury and the things that make people feel luxurious. Moreover, this will delve on luxury brands, and brands that have survived through the various challenges and barriers in international marketing.

Luxury goods in international market

Luxury can be viewed in terms of its psychological value. A person who wears luxury occupies a status in society, and this is true in any kind of society. Luxury exhorts a distinct type of consumption experience that parallels a person’s self-concept. Luxury brands are not similar with major or popular brands because they are always unique and exceptional, or at least, that is what luxury ‘aficionados’ think.

Some researchers argue that consumers can describe luxury by identifying the names of luxury brands, such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel, and Calvin Klein. However, consumers might find it difficult to identify the essence of luxurious things (Roper et al. 2013).

A luxury brand is distinct because of its tendency to diverse and continually change that it operates ‘as an experiential brand’ (Fionda & Moore 2009, p. 348). A luxury brand’s core characteristics differentiate it from the other major brands, and this includes price, image and exceptional quality.

Luxury cannot be separate from things synonymous with beauty. ‘Like light, luxury is enlightening. They offer more than mere objects: they provide reference of good taste. Luxury items flatter all senses at once. Luxury is the appendage of the ruling classes’ (Kapferer 1997, p. 253). This poetic meaning of luxury exudes the delicate, pluralistic and emotional concept of luxury product, but it also emphasises that luxury is not easy to define.

Dimensions of the luxury brand

Table 1 (Appendix 1) displays the dimensions of the luxury brand. In brief phrases, this table provides key points in successful brands’ strategies in their particular segment. Table 1 is an overview of the key models identifying the luxury fashion brands’ dimensions.

SOURCE: Adapted from Fionda and Moore (2009, p. 350)

Table 1 has the following explanation.

- Nueno and Quelch (cited in Fionda & Moore, 2009) emphasises the significance of product excellence to enhancement of a realistic luxury brand, and gave importance to controlled distribution.

- Bernard Arnault, the CEO of Louis Vuitton (LVMH), focuses on the importance of corporate identity, culture and spirit, but also indicates the significance of creativity in luxury brand development.

- Likewise, the Morgan Stanley Dean Witter brand emphasises the dimensions from a practitioner’s viewpoint.

- Phau and Prendergast emphasises four key luxury features, but indicate that their focused features of ‘recognised brand identity, quality, exclusivity and customer awareness’ are significant components of the luxury brand (Fiona & Moore 2009, p. 349).

Beverland (cited in Fiona & Moore) indicates that the contents described in table 1 are not limited. Several studies show that luxury brands are among the most distinguished and admired of consumer brands globally (Vickers & Renand; Brooke, cited in Fionda & Moore, 2009).

Concepts and theories

Studies about luxury goods merely emphasised material possessions and did not focus on the differences between ‘luxury hospitality services and luxury goods’ (Yang & Mattila 2014, p. 527). The luxury industry needs more empirical studies which should focus on the relationship of luxury hospitality services and luxury goods. However, luxury firms are doing their own part by conducting in-house and out-house corporate social responsibility focusing on such relationship.

Growth and rate of value are characteristics of the luxury goods sector, in which in 2007 it registered a value of US$130 billion and growth which far outpaced other consumer goods (Fionda & Moore 2009). Growth in luxury consumption is primarily due to increased wealthy consumers in largely emerging economies and lower unemployment in those countries (Truong et al., cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014). Different societies have been too keen to luxuries.

The ‘Rarity Principle’

In 2011, worldwide sales of luxury goods increased 10 percent, according to the studies of Bain & Company (Rothery, cited in Cavender & Kincade). Growth of this sector will continue because of ‘emerging markets, a growing number of wealthy individuals around the world, and growing demand among middle market consumers due to luxury’s aspirational nature’ (Truong et al., cited in Cavender & Kincade, p. 233).

The world is witnessing a growing phenomenon called mass luxury, or ‘masstige’ (Yang & Mattila 2014, p. 526), which is an increasing threat to the luxury industry. There is that rarity principle applied to the luxury products, to include customer’s need for ‘uniqueness in luxury consumption’ (Kastanakis & Balabanis; Kim et al; Lertwannawit & Mandhachitara; Tynan et al; Vigneron & Johnson; Wiedmann et al., cited in Yang & Mattila 2014). With masstige, the rarity principle is lost.

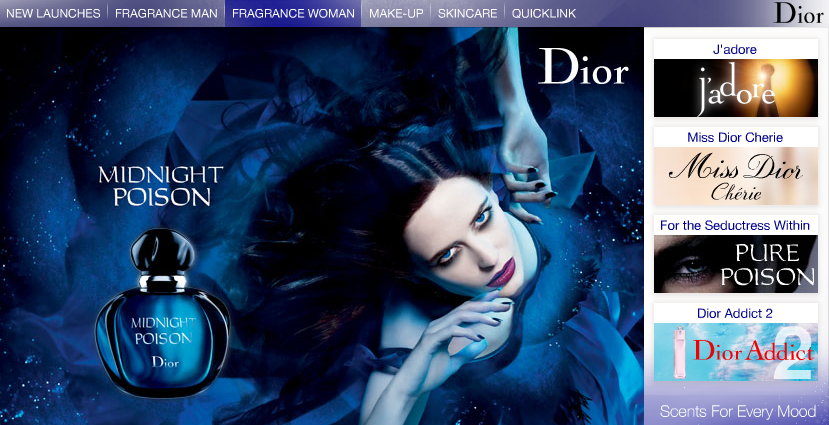

Several factors affected the growth in the industry, particularly economic crises, terrorism, and natural catastrophes, among others. The luxury industry is a non-cyclical sector and star brands have prevailed, such as Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Parfums Christian Dior, which have showed flexibility and leadership in improvement activities from the latest economic downturns (Galloni, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014).

The role of suppliers is not to be ignored as they are one of the keys to a successful luxury sale and increased profit. Suppliers of luxury fashion goods have formulated business strategies by means of extending their geographic coverage and products’ accessibility through opening what they called ‘dedicated points of sale’ (Euromonitor; Twitchell; Vickers & Renand, cited in Fionda & Moore 2009, p. 347). Increased media attention in luxury goods consumption and the growing luxury brand awareness as a significant component of consumer culture triggered the development of the luxury market.

Categories of luxury goods

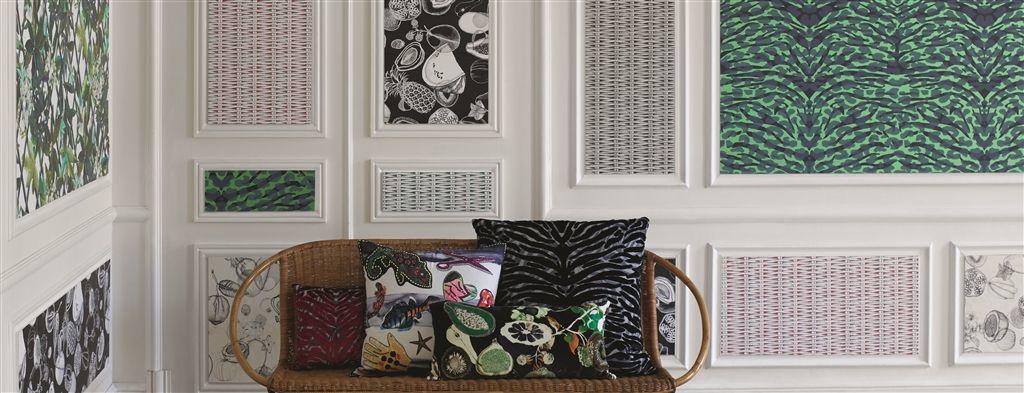

Luxury goods are categorised into ‘fashion (couture, ready-to-wear and accessories); perfumes and cosmetics; wines and spirits; and watches and jewellery’ (Jackson, cited in Fionda & Moore, 2009, p. 348). New categories have been added, such as: luxury cars, hotels, tourism, private banking, home furnishing and airlines, among others (Chevalier & Mazzalovo, cited in Fionda & Moore, 2009, p. 348).

Fashion is closely bound to the flow of time; but luxury goes for timelessness. Luxury and fashion are about two different worlds moulded into one, both economically significant, but different from each other (Kapferer & Bastien 2009).

The luxury fashion goods sector has been considered the largest proportion of luxury goods sales, accounting for about 42 percent share of the entire sales in 2003 (Mintel Report; The Economist, cited in Fionda & Moore, 2009), and with the strongest growth in 2007 (Bain, cited in Fionda & Moore, p.348).

Moreover, studies have shown that the branding process of luxury fashion goods is more complicated than other sectors due primarily to the fast changes in this sector. The fashion season appears, but when the season ends other sectors are dormant (Okonkwo; Jackson; Moore & Birtwistle; Bruce & Kratz, cited in Fionda & Moore, 2009), whereas the fashion luxury goods sector prevails and continues to grow. Additionally, marketing of fashion goods has always been multifaceted, with a lot of capital to consider, complex in terms of operating scale and the activities of several fashion companies to control distribution. These costs and corresponding activities make the fashion luxury goods exceed over the others.

In the luxury fashion, value of products is added due to craftsmanship, innovation, impeccable style, superiority, and top pricing, i.e. higher prices than the mere fashion brands (Chevalier & Mazzalovo, cited in So, Parsons & Yap, 2013). Customers may see these characteristics of the luxury brands as something that can give them benefits in terms of social status, affirmation and sense of being part of an organisation that values them (So, Parsons & Yap 2013, p. 404).

Most luxury companies, such as LVMH, Gucci Group, Prada, and Richemont Group, exhausted their capital in developing their brands, and this is all part of their plans and strategies as international luxury marketers. Authors So, Parsons and Yap (2013) suggest that ‘a strong brand identity is fundamentally linked to a relevant, clear, and defined branding strategy’ (p. 404). Luxury firms have to create discernible brands in reciprocating customers’ loyalty and brand preferences (Chevalier & Mazzalovo; Okonkwo, cited in So, Parsons & Yap).

The traditional way of luxury firms is to use ‘high-status brand names’ (Choo et al., cited in So, Parsons & Yap, 2013), but current luxury customers show attachments to the brand, or closeness and association with brands, in their decision making purchases (Bain & Co; Choo et al., cited in So, Parsons & Yap). Luxury firms are now focused on building ‘customer emotional attachment,’ rather than on ‘building social status,’ because this is what customers want. Emotional attachment not only adds value but also demands a higher, sustainable type of loyalty (Part et al., cited in So, Parsons & Yap).

Fashion luxury retail buying

Fashion has always been linked with creativity. In the United States alone, the fashion industry has an annual output of $200 billion, which far surpasses other sectors. Clothing is one of basic necessities and one of the most fundamental motivational needs in Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

To some degree, all of us participate in the world of fashion. Fashion is an economic source for most of the nations of the earth, and the multiple cultures anywhere in the world. It is regarded as ‘a window’ for society’s progress and change. All the other aspects of social life (e.g. politics, the sciences, entertainment, and so on) are hard to discern without an application of fashion of some sort (Hemphill & Suk 2009).

Fashion buyers are ‘cultural agents’ that act as go-between in the relation of production and consumption. They figuratively create products with high cultural significance, which help to shape and forge tastes in the process.

Kincade et al. (cited in Perry & Kyriakaki, 2014) define retail buying as ‘the decision-making process by which individuals in an organisation establish end consumer requirements for products and subsequently identify, evaluate and select among alternative brands and suppliers’ (p. 88). For a fashion retail brand, customers select own-label product from different garment suppliers, while for independent fashion retailers, buyers choose branded product from different fashion brands.

Within the luxury fashion sector, independent retail buyers buy garments and accessories from their brand’s collection, and do not go to garment makers but their own brand’s representatives (Entwistle, cited in Perry & Kyriakaki, 2014). At the luxury segment, the manufacturer controls the industry in that ‘brands exert considerable influence over the supply of their products to independent retailers by limiting distribution as well as setting demands as to how the products should be sold, displayed and marked down in retail outlets’ (Entwistle, cited in Perry & Kyriakaki, 2014, p. 88).

Approaches to brands

Examples of luxury brands include Louis Vuitton, Porsche, Kenzo, Cartier, Ferrari, Chanel, Christian Dior, Mercedes Benz, Gucci, Rolex, Mont-Blanc, Ferragamo, and much more. Research has shown that in the UK, people wanted to look luxurious and materialistic, thus, the demand for eye-catching and status products (Phau & Prendergast 2000).

Traditional approaches to brands provided concepts of the crossing point between consumers and marketers from the marketer’s viewpoint, which makes the consumer an object of research.

The manager may ask: ‘How do my techniques improve selling such as brand advertising, brand awareness and ultimately customer loyalty?’

Kapferer and Bastien (2009) argued that many luxury brands failed because the rules of classical marketing were ignored, in which the customer has to play a part in the creation of value for the product. Without the co-creation aspect, the brand loses value. The authors tend to identify this change as some kind of ‘bad marketing,’ rather than of the relationship between consumer and marketer.

Schembri (2006) argues that co-creation follows the ‘managerialist track,’ with a focus on brand value and allows the customer to co-produce that value with marketers: ‘The point is that the customer is required to co-produce value. However, a nondualistic ontology suggests the customer is required to co-construct the meaning of services’ (p. 389). Customers possess and give meaning to value by means of social construction using their language for the brand.

Brand positioning

Kapferer and Bastien (2009) describe the luxury brand: ‘This image is born of itself – not of surveys showing where there might be a niche or a business opportunity, but in the very spontaneous identity of this man, his background and his idiosyncracies. One should use all that helps to forge authenticity, psychological and social depth, and that creates close bonds with the psyche of clients who will be seduced by this identity’ (p. 316).

The luxury brand should be able to tell a story, a story about the owner or designer. The brands Coco Chanel and René tell their own stories; Ralph Lauren or Tod also provide a story of something invented from scratch. Stories appeal to the emotion and build an attractive identity, and travel rapidly as in rumours (Kapferer & Bastien 2009).

The luxury brand should be difficult to earn, and the more it is inaccessible the more it is desired. The time factor is equally important because it taps the psychological aspect of the consumer, meaning ‘the time spent searching, waiting, longing’ can lead to quick access to the product through mass distribution, through the different marketing methods (Kapferer & Bastien 2009). The internet is the fastest and most economical way of accessing luxury items, and they are displayed like delicate glass products in state-of-art medium, the websites.

Corporate branding

Corporate branding is a comprehensive management technique adopted by marketers to expertly form a distinct corporate identity. Corporate branding has become a trend in the marketing literature as corporate brands can ‘add value to the products and services’ of the firm (Harris & de Chernatony, cited in So, Parsons & Yap, 2013, p. 405).

Strong brands (e.g. Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Gucci, etc.) provide elusive values hard to copy or imitate. Because of this, a strongly cultivated corporate brand delivers a sustainable competitive advantage that triggers loyalty (Harris & de Chernatory; Hatch & Schultz, cited in So, Parsons & Yap, 2013).

The main idea of corporate branding is to accept a monumental brand name that can represent all products of the company when interacting with major stakeholders that include customers, employees, and shareholders. Can we not see this image in Louis Vuitton, as pictured in their larger than life icon, shown in figure 3?

Internet as global medium: does it have a role in marketing of luxury brands?

The traditional ways of marketing and brand position are often questioned. The traditional methods include television, print and radio and are considered lacking in necessary appeal to the increasingly sophisticated consumers, especially youth who are more hooked in computers and the internet. The growth of internet is growing because of the wider range it can reach.

Organisations and businesses use websites to interact with customers, confer with and acquire product information. Use of websites is a new form of marketing as it offers opportunities to develop effective relationship marketing in traditional and emerging markets (Roberts & Ko, cited in Okazaki, 2005), and it is the cheapest way to access to the global market, particularly for exporters (Dou et al., cited in Okazaki, p. 88).

Internet traffic is a term applied to the volume of internet usage with the United States having the largest share, a record of 42.65 percent, seconded by China, 6.63 percent, and then Japan with 5.24 percent (Europemedia, cited in Okazaki 2005). Europe cannot be far behind as its internet traffic is also fast increasing. Multinational corporations (MNCs) in Europe are pressured to create marketing strategies via the internet (Laroche et al., cited in Okazaki, p. 88).

The internet is a virtual environment wherein luxury firms can acquire mass exposure, but there are challenges. Several brands are still slow in establishing web presence, and some like Chanel and Hermès continue to resist what they called integrated e-Commerce, which makes consumers wanting for more and resort to buying fake luxury goods from traders proliferating all over cyberspace (Okonkwo 2009).

A major existing absurdity is present in creating and maintaining the craving and exclusiveness characteristics of luxury brands on the mass and egalitarian cyber world and at the same time retaining and developing the equity of the brand. Another challenge that confronts luxury brands in conducting websites is the job of increasing sales and the risk of over-exposure while having a delicate perception of limited supply. These are internet characteristics which tend to be opposite luxury’s main components.

We know that the internet and e-retail can go to the far reaches of the world, wherein situations that occur are detrimental rather than beneficial to luxury goods. Okonkwo (2009) enumerates the advantages or disadvantages of luxury brands’ reaching to their consumers through their websites:

‘… a pull marketing approach where customers are drawn to information and purchases, rather than a push medium where customers are driven by advertising; a lack of physical contact with the goods and human contact with the sellers; a low switching cost as it takes only one click to switch between websites; fast and convenient; more product variety and access to viewing them; availability and accessibility irrespective of time and location; less powerful sales as it is easy to say no to a computer; a universal appeal and uniform information’ (Chaffey et al.; Dennis, Fenech & Merrilees; Harris & Dennis, cited in Okonkwo, 2009, p. 304).

These features tell us that the internet is there available to a great mass of people from different geographic areas around the globe, which is not in conformity with the niche consumer base that luxury brands have been targeting. There is also the lack of physical contact with the goods and the sellers. Luxury products are considered products that appeal to the senses, which tell us that the senses of visuals, smell, touch and feel are needed in selling luxury goods. In Okonkwo’s (2009) analysis, selling luxury goods over the internet is not beneficial – to a certain extent – for the companies or sellers of luxury products. However, websites are effective for communication between seller and buyer.

America’s popular brands use several approaches for their markets in Europe. These markets have distinct cultural and linguistic attributes, but are almost similar in terms of socioeconomic conditions and technological infrastructure. They also use online marketing for low and top brands.

These conditions and technological environments are presented in table 2.

Table 2. is consolidation of 2001 data.

Legend: amillions, per report from national statistical offices (World Advertising Research Center, cited in Okazaki, 2005); bUS$, constant 1995 prices (world Advertising Research Center, cited in Okazaki, p. 88); dpercentage of population having been online in last 14 days (World Advertising Research Center, cited in Okazaki); epercentage of population ever purchased online (World Advertising Center; fUS$ billions, B2C (www>emarketer.com; www.baquia.com; www.aece.org, cited in Okazaki, 2005).

Top brands have placed great significance to online communications as these attract customers from the different parts of the world. There are various areas in which firms compete (e.g. price, selection, and delivery of the product), and websites can help in the firms’ quest to be on top. Through websites, customers can shop and come back for more if they perceive the attractiveness and quality of the product. With this, firms need to study and research their customers, e.g. a cross-cultural research, that should focus on what functions can be standardised or customised.

Okazaki’s (2005) study aimed to identify the extent of global brands in adopting standardisation using online tools created in European markets. Websites for premier American brands for the UK, France, Germany, and Spain were investigated and their strategies recorded. Okazaki’s (2005) methodology used content analyses to clarify the relation between the website content and the standardisation strategy. The study had this hypothesis: ‘American brands utilise a diverse range of brand web site features to effectively determine the degree of web site standardisation in multiple markets’ (Okazaki 2005, p. 288).

Okazaki’s study could contribute to the literature in two possible ways. First, internet’s success to impact marketing has instinctively favoured proponents of international advertising standardisation, due to the fact that consumers with a computer and internet connection can access websites anytime and anywhere around the world. This phenomenon can be considered as ‘cross-cultural marketing communications’ at its best.

Roberts and Ko (cited in Okazaki, 2005) suggested that websites can enhance ‘corporate and brand consistency and strong equity, while simultaneously allowing flexibility in being culturally sensitive’ (p. 288). Localisation and standardisation are two situations that can be applied at the same time to websites. This means we can consider customised processes and standardised or the same methods for different cultures for these websites, and it can be effective for top brands for the different cultures around the world.

Standardisation of international advertising has been a subject of research by many researchers due to the increasing rise of global media like the internet, and the ‘increasing homogenisation’ of customers’ preferences around the world (Duncan & Ramaprasad; Harris; Samiee et al., cited in Okazaki, 2005, p. 90).

The United States is recognised as the world leader in providing global luxury brands, many of which are seen as symbolising high status and quality craftsmanship (Anholt, cited in Lee, Knight & Kim, 2008). Luxury brands based in the United States possess the necessary prestige and quality.

International firms have been attracted to developing brands because of studies that by 2010, approximately 90 percent of the world population would be residents of developing countries, and the rest will be living in what are now developed countries in North America and Europe. An emerging global middle class will reside in developing countries (Lee, Knight & Kim 2008).

Branding strategies

Branding is a basic idea in marketing. Consumers make their decisions after they have scrutinised the brand name, which has specific image, price, worth and quality. Brands maybe classified into three types of identities: national brands, or products manufactured domestically; local private brands; and international brands (Ghose & Lowengart 2001).

Brands must have proper management from the time they are introduced into the market. Brand owners aim to provide consumers with a unique touch of their brands through improved quality of life along with their product. Through living with the brand, consumers are guided with their decision-making process and purchasing behaviours (Kapferer, cited in Veg-Sala & Roux, 2014).

Even if brands acquire changes due to societal and technological factors, a brand must be able to retain its basic and ‘stable narrative to manage various strategies’ (Floch, cited in Veg-Sala & Roux, p. 104). A brand narrative refers to the ‘nature of figurative discourse (with characters that perform actions)’ (Greimas & Courtés, cited in Veg-Sala & Roux, p. 104), or a temporal series of functions.

Marketers introduce brand extension strategies with the hope of acquiring success for their particular brands. However, attaining extension success in brand strategies is not simple. Researchers emphasise the ‘fit’ factor between the original brand and the extension. The brand will be more successful if fit is emphasised (Veg-Sala & Roux 2014).

According to their roles in contracts, brands are regarded as types of legends and myths wherein they have made their names enshrined that made them legitimate work (Holt, cited in Veg-Sala & Roux, 2014). One example of a brand legend is Levi’s advertising, which says ‘Enter into the legend,’ and portrays a man wearing jeans and boots, with a saddle in hand, showing the conquest of the West. The signs symbolise masculinity and men of action (Hold & Cameron, cited in Veg-Sala & Roux). Legitimacy emphasises adherence and permission by law, and is coherent with equity, justice and reason.

Marketing strategies of specific luxury brands

Not all markets in the world are open markets and some international firms have to form partnerships and alliances in order to penetrate domestic markets. Firms have to use licensing partnerships with international firms to access knowledge on marketing skills, quickly penetrate into international or emerging markets, minimise risks and reduce costs of conducting business in such markets, and avoid tariff and non-tariff obligations from other countries (Contractor & Lorange; Kotabe & Swan, cited in Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996).

Partnerships may be in the form of joint ventures, or partnership where the organisation of the host country acquires more than fifty percent of the shares. Other countries require foreign firm to acquire only about forty percent of the shares of stock. However, when China opened up to world market and other authoritarian regimes liberalised their economy, other governments eliminated the policy in which the organisation of the host country controlled majority of the shares (Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996).

Many studies have focused on the rationale for international partnerships, including joint ventures. The studies found that choosing the appropriate partners, aligning strategic and economic incentives of the partner firms, and making use of ownership control, determine the success of the partnership and reduce the risk of opportunistic behavior, which is common in inter-organisational relationships (Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996).

Partnerships and alliances in organisations became increasingly important when organisations started to downsize and focus their resources on core functions because of economic factors, globalisation and technological innovations (Doz & Hamel, cited in Fuller & Vassie, 2002). This trend first led organisations to rely greatly on contractors which had the efforts of providing and maintaining the level and quality of the support services needed in their operations. This dependency on contracted organisations placed doubt on the organisations’ trustworthiness and capability, and whether they had business philosophies that could provide the quality service they were supposed to deliver.

To remedy this situation, organisations focused on moves that would enable each partner to achieve harmonising but distinct objectives (Bresnen & Marshall, cited in Fuller & Vassie, 2002, p. 451). In line with this, the UK Department of Trade and Industry (DTI, cited in Fuller & Vassie, 2002) formulated the ‘Partnerships with People’ program and proposed that, while everyone can play a role in the organisation’s success, effective partnering methods within organisations should improve the competitiveness of UK industry’ (Fuller & Vassie 2002).

Cultural alignment and adaptation between partners is significant in success of partnerships and alliances (Bresnen & Marshall, cited in Fuller & Vassie, 2002). Cultural alignment creates mutual understanding and co-operation between organisations on a partnership and reduces conflicts as cultures create discords and hindrances to cooperative ways of working.

Potential partners should be able to assess their organisational cultures before going into joint ventures (Doz & Hamel; Child & Falkner, cited in Fuller & Vassie, 2002). Advantages of enhancing cultural alignment of partner organisations include creation of ‘common reference points, understanding, practices and behaviours and a reduction in the levels of uncertainty’ (Fuller & Vassie 2002, p. 541).

Building trust in partnerships

Trust is important in international marketing. The concept of trust between international firms has been examined to find out how this is established and how firms reach partnership agreements. Trust in interpersonal relationships is defined as ‘the willingness of one person to increase his/her vulnerability to the actions of another person’ (Lewis & Weiger, cited in Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996, p. 2008). It is important in economic exchanges as parties expect each one will behave in accordance with any commitment, be honest in negotiations, and not to take advantage of the other, even when the opportunity is available (Hosmer 1995, cited in Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996, p. 2008). Most importantly, trust is significant in society as ‘a collective attribute based upon the relationships in a social system’ (Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996, p. 2008).

Trust enhances ‘the efficiency and effectiveness of communication’ (Blomqvist, cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008, p. 161). It is an effective tool in organisational partnerships as relationships are under supervision of individuals. International firms in partnerships can develop trust as each partner expects obligations are fulfilled. The ‘expectations of behavior’ between members of the partnership has two elements, namely structural and behavioral (Hosmer; Madhok, cited in Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996).

The structural component is about building trust enhanced by the exchange of resources between partners, and is important for the creation of the relationship. This is significant if one partner may become more at risk in the relationship due to an imbalanced dependence (Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay 1996, p. 1008). The behavioural aspect of trust refers to the confidence aspect in exchange relationships and the eagerness ‘to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence about’ (Moorman, Deshpande & Zaltman, cited in Aulakh, Kotabe & Sahay, 1996, p. 1008).

When members of organisations are well informed of the role of trust and the effects of the different types of organisational trust, theoretical and managerial consequences are expected, particularly in a knowledge-intensive organisation. However, a detailed discernment of the various types of trust on innovativeness would be important.

Ellonen, Blomqvist and Puumalainen (2008) argue: ‘Managers could consider more carefully how different dimensions of interpersonal trust, i.e. based on competence, benevolence and reliability, affect different dimensions of organisational innovativeness’ (p. 161). An example is that when a firm wishes to enhance ‘behavioural innovations,’ and the kindness element of vertical interpersonal trust is of utmost importance, there should be particular emphasis placed on manager’s behavior that affect the particular benevolent act. Organisational trust can also be developed by institutionalising some HRD functions in organisations (Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen 2008).

Organisational trust has great significance and is discussed in different areas of discipline, to include economics (Sako, cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008), sociology (Luhmann, cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen) and psychology (Blau, cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008).

Interpersonal trust has two elements: lateral and vertical. Lateral is about trust between employees, and vertical trust points to trust between leaders and employees (Costigan, cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008). Organisational trust refers to positive expectations of people over the capability, trustworthiness and benevolence of organisational members, and this includes ‘institutional trust within the organisation’ (Mayer et al.; McKnight et al., cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008, p. 162).

Institutional trust is different as it does not refer to personal trust. Related to this is ‘procedural justice,’ which is about fairness in HR processes and is positively linked with employee attitudes, like loyalty to the organisation (Pearce et al., cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008).

We can define impersonal trust by looking at the roles, systems and statuses from which suppositions are drawn in reference to the reliability of an individual. The interpersonal aspect is about interaction in a particular relationship. Institutional trust can be determined by the efficiency and the equality of the systems within the organisation. Institutional trust refers to one’s belief that the needed impersonal structures are present to motivate one to act ‘in anticipation of a successful future endeavour’ (McKnight et al., cited in Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen, 2008).

Institutional trust has two forms: situational normality and structural assurance. In situational normality, the belief comes from the appearance of normal and customary situation, or that things seem normal and in proper order. In other words, it is the belief that an endeavour will be successful as the situation is normal. The other form, which is structural assurance, refers to the belief that there will be success because of the presence of contextual conditions, such as ‘promises, contracts, regulations and guarantees (structural safeguards)’ (Ellonen, Blomqvist & Puumalainen 2008, p. 162).

The concept of institutional trust is illustrated in figure 4.

Methodology

Introduction

This dissertation used literature review and case studies as research methods. We conducted extensive case studies on luxury firms that have been successful and even those who failed in international marketing.

Case studies provide powerful concepts in the study of contemporary phenomena in their real-life setting because of the qualitative complexities (Yin 2013). A case study is a democratic way of focusing on certain issues as it ‘does not follow any stereotypic form’ (Yin 2013, p. 211).

In a case study, the researcher likes to compose or write what he/she has researched. Writing is an important activity in case study research. Even those without experience in composing like to conduct case studies because it allows them to enhance their writing skill. Being good at composing can lead the researcher to write good case studies. A motivated researcher sees composing activity as an opportunity rather than a burden in writing the report or research.

On the other hand, literature review has no definite methodology and is a narrative of past writings about a topic or subject of dissertation. It is composed of ideas and researches of other authors who conducted studies on the subject. In doing this, we are required to cite the names and works of the authors or researchers who have done those studies (Jesson, Matheson & Lacey 2011).

A literature review is a document of academic significance, has a rational methodology by itself, and clearly states the aims, objectives and rationale of the dissertation, to include an analysis and interpretation of the works cited therein by the student doing the literature review (Blumberg et al., cited in Jesson, Matheson & Lacey, 2011).

In searching for articles or sources for this dissertation, we used key words, such as luxury products, international marketing, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Calvin Klein, culture, multi-cultural differences, luxury brands, globalisation, Middle East luxury firms, U.S. luxury brands, European luxury brands, standardisation, customisation, glocalisation, international brands, marketing strategies, and much more.

Case studies

Louis Vuitton

Since the 1850s, the luxury goods industry has thrived, particularly in apparel. Louis Vuitton and Möet-Hennessy merged and conglomerations became a leading ownership structure in the industry.

The conglomerate LVMH, with the star brand Louis Vuitton, was the subject of a study. Two major brand valuation reports in 2012 awarded Louis Vuitton the Interbrand Best Global Brands and Brands Top 100. This top ranking reflected the company’s financial and marketing leadership in the luxury segment of the retail industry.

During the time the two companies merged, Möet-Hennessy was a manufacturer and retailer of wines, spirits, and perfumes. Upon its merging, it is now known as Möet-Hennessy-Louis-Vuitton (LVMH), with Bernard Arnault as chairman and CEO in 1989. Arnault’s strategies became a model for leadership and his style was envied by competitors Gucci and Prada. In terms of position and profit, LVMH has become a leader in the luxury goods industry (Mintel, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014).

In the aforementioned study, the findings indicate that four goals were themes in the company’s brand strategy which helped enhance brand identity and marketing vision: ‘competitive and financial strength, strong brand performance, consistency important in communication of the brand concept, and social and cultural responsiveness’ (Heding et al., cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014, p. 235).

The brand concept is fundamental to the brand and ‘a solid building block’ for improvement of the ‘brand identity’ (Okonkwo, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014, p. 237). Brand identity emerges from the brand concept and has become part of the brand strategy. LVMH develops a collection of successful brands with apparently defined brand concepts, such as Bulgari, Pucci, Fendi, and TAGHeuer. However, there were brands that had to be divested (of the shares) from the company, such as Lacroix, Hard Candy, Urban Decay, among others, for reasons that they failed the company’s objectives (Cavender & Kincade 2014, p. 237).

Louis Vuitton’s brand identity was measured through ‘brand image and brand personality’ (Cavender & Kincade 2014). Accordingly, brand image is the understanding of a brand formed in the consumers’ thinking based on the way the brand is presented. Brand personality is the true appearance, or ‘true self,’ of the brand (Okonkwo 2009). Data analysis was conducted which produced the brand protection, and was used as the third measurement.

CEO Arnault showed his management skill by restructuring with Dior Couture brand, once France’s prestigious brand but became diluted later on in the 1970s. Dior Couture’s management experienced overhaul, in which Arnault applied strategic goals purposely to regain tight control in operations, production and distribution, including global expansion, and providing ‘modernity into the heritage brand’ (Socha, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014, p. 239).

Then, in the 1990s, Yves Carcelle led the new management and overhauled Louis Vuitton’s brand identity anew by tapping the brand’s untarnished reputation for craftsmanship. Management created an artificial shortage by limiting production and release and distribution of products, and diversifying product innovations through new design style and materials. This was to counter the phenomenon ‘masstige,’ which has been a threat to luxury goods industry because it diminishes the concept of rarity in the luxury industry. Arnault’s aim of brand protection was successful in their acquired brands.

Louis Vuitton’s marketing vision aimed for brand positioning, both inside and out. Brand positioning is a construct of brand identity and helps firms to produce ‘the optimal location in the minds of existing and potential consumers’ (Keller, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014, p. 240).

Luxury brands tend to be symbolic in nature and acquire high brand awareness that goes beyond their customers. This provides opportunities for firms in the enhancement of their marketing vision. Louis Vuitton is easily recognisable as the ‘LV’ in brown canvas handbags as can be seen in television and print advertisements. They convey the brand personality, even without the brand name (Socha, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014).

Louis Vuitton introduced abstract advertisements, in which they do not show the name of the product but provide ‘Core Values’ campaign, displaying the brand’s essence and exposing the symbolic nature of the company. By capitalising on consumers’ senses and bringing them to a somewhat imaginary world, however briefly, Louis Vuitton is able to exude a stronger, deeper association in the subconscious of current and potential customers, than the product-related associations produced by the brands in less targeted goods categories (Cavender & Kincade, 2014).

Arnault was interviewed by Harvard Business Review, and he said: ‘The last thing you should do is assign advertising to (a brand’s) marketing department. If you do that, you lose the proximity between the designers and the message to the marketplace. LVMH keeps the advertising right inside the design team’ (Wetlaufer, cited in Cavender & Kincade, 2014, p. 240).

Louis Vuitton has more than fifty brands for its valued customers. These are luxury brands, according to this study’s definition of luxury, as they are different from ordinary consumer products. The brand boom in Japan is dominated by Louis Vuitton, which hit the top leadership for luxury brands, above other luxury brands Hermès, Tiffany and Coach. In store sales in Japan, Louis Vuitton garnered more than 3.0 billion yen.

Louis Vuitton’s 4 Ps

Product quality is of utmost importance for Louis Vuitton. The company conducts extensive quality control, but not to exceed the needed or precise quality as has been the company’s requirements, although researchers opined that Louis Vuitton has ‘absolute quality’. The quality of a handbag, for instance, requires that the consumer’s things and valuables can be contained ‘with comfort’. A Louis Vuitton luxury handbag means it has a respectable quality, pays attention to even small things, and it has a story to tell as in any other luxury item (Nagasawa 2008).

A Louis Vuitton product exudes the principles and creativities of the House of Vuitton. The products have 18 principles which propose elimination of counterfeit products, prohibition of ‘appraisal of authenticity,’ banning of ‘second-line operations,’ banning of licensing, preventing adverse assessment favouring other luxury brands, preventing ‘entry-level branding,’ and promoting other ethical standards for luxury marketing (Nagasawa 2008, p. 43).

Louis Vuitton luxury products have higher prices compared to other luxury items. The company stresses that what they promote is value and not price of the product. As in other luxury brands, price has to be distinct. Louis Vuitton managers in different countries assign different prices for their luxury products, but they are also higher compared to other luxury items. Louis Vuitton prices are always high in Japan and this was followed by other branches in many countries.

In terms of pricing, Louis Vuitton exalts the principles of prohibiting very high prices, promotion of appropriate pricing, banning bargain sales, banning marketing in value sets, banning unexpected price changes, banning the principle that the company is only up for money, and promoting ‘prestige pricing,’ among others (Nagasawa 2008, p. 44).

Place or distribution as one of the 4 Ps for Louis Vuitton promotes ‘limited distribution,’ and not wide distribution methods or channels suggested by other brands. The principle is that information about and source of the Louis Vuitton products should only come from a limited source, so that it can provide accurate information about quality products.

Louis Vuitton’s ads centre on the product. The company emphasises publicity, or as a firm ‘taken in the media’ because of its value to the public. Louis Vuitton does not advertise in television and is principled on charm with legend; it wants its customers form a line to buy their products in stores; promotes excessive parties; and promotes allegiance to their products, among others (Nagasawa 2008, p. 47).

Louis Vuitton’s branding fosters the Toyota Production System which is about continual improvement. Production is aimed at continuous improvement so that customers will not get bored and continue to be loyal to their product and repeat purchase. The company emphasises artisanship or craftsmanship because that is how the company started, through sheer determination of providing artful designs to loyal customers. However, Louis Vuitton is not confined to artisans alone but also to creative designers. By pairing designers and artisans, real workmanship and creativity are produced to provide quality luxury goods for their customers.

Louis Vuitton also promotes selective marketing, which is a particular type of marketing that focuses on their products. This type of marketing targets the particular segment of luxury products. International marketers have to conduct cross-border segmentation, wherein the firm identifies identical target customers in the international market. The marketer finds for potential customers with the same needs across borders. This is a challenge for marketers because different consumers from different nationalities and cultures have distinct needs afforded by their cultural and social orientations (Ghauri & Cateora, cited in Guhr, 2008). Cross-border segmentation relies on several factors, such as geographic, economic, ethnic, demographic, and lifestyle factors.

This study focuses on a particular sector, the luxury goods industry, which has a distinct type of segmentation. Marketing segmentation focuses on the marketer’s skill to collect, study, and act on data about customers and the marketing environment. Customer orientation becomes effective when customers provide information that can be transformed into good design and quality products. However, individual attitudes toward information and governmental regulation of that information are a key consideration for all marketers. There is likely to be great difference in these attitudes and policy across different cultures and markets (Guhr 2008).

Gucci

Gucci is a favourite of brand aficionados throughout the world. This was the result of an online survey in which 25,000 respondents were asked about their brand preference. The respondents chose Gucci on top of the list, and included Chanel, Calvin Klein and Louis Vuitton, along with Christian Dior.

Gucci management had reason for this and they attributed the success to Mark Lee, their company president since 2004. Sales jumped in 2007. Fashion director Michael Macko (cited in Ruiz, 2008) indicated that Gucci is an iconic luxury brand, its signature handbags with a logo exhibits what they call the best of branding (Ruiz 2008).

Guccio Gucci originally made leader handbags in the 1920s. The small shop grew into a large luxury luggage company, with the double-G logo. Other luxury products bearing the Gucci logo are belts, scarves for women, cocktail dresses, but the best money maker for the company are luxury designer handbags (Ruiz 2008).

Gucci’s marketing strategy includes the ‘Bag Borrow or Steal,’ which is popular over the internet and patronised by those who cannot afford full price for Gucci handbags. Gucci handbags become affordable and luxury ambitious aficionados can carry them even if they do not have the hundreds of thousands of dollars for such luxurious items of Gucci. ‘Bag Borrow or Steal’ can also provide for sunglasses and jewellery (Boone & Kurtz 2015, p. 455). Gucci handbags are sold in exclusive stores and do not allow discounts.

Gucci’s corporate social responsibility activities include donating proceeds of a project, like the ‘Gucci loves New York,’ a promotion the company started when they opened up a new store in Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue (Ruiz 2008). The company promotes CSR as a way of improving relationship with the community and the shareholders.

Calvin Klein

Calvin Klein specialises in jeanswear and underwear, but also men and women’s coats. This fashion luxury company was founded in 1968 by Calvin Klein. The company became a leader in fashion coats designs and had won awards for its modest but fashionable styles. Calvin Klein also sells designer jeans and one of its popular endorser was Hollywood actress, Brook Shields (Ruiz 2008).

Calvin Klein is one of the three groups of the firm PVH, the other two being Tommy Hilfiger and Heritage Brands. PVH acquired Warnaco in 2013 and has continuously expanded their businesses of luxury brands to many parts of the world (PVH: our company, our strategy 2015). The company was rated number 8 in 2013 study by ‘Media Radar,’ along with Louis Vuitton, Chanel and Christian Dior. The ranking was made by the ‘Most talked about Fashion brands of 2013’ (cited in Feloni, 2014).

Unlike Louis Vuitton, Calvin Klein offers competitive prices for its products by means of constant promotions through multi-media and stronger loyalty marketing. This is a luxury brand that capitalises on designer brand positioning with affordable prices.

In the literature, we noted higher prices for luxury brands and explained that this is needed for luxury items as companies wanted to emphasise value, and not pricing. In the case of Calvin Klein, they offer competitive prices and couple this with ‘premium designer positioning’. Then, why is Calvin Klein on top?

There is that element in luxury brands marketing, which is uniqueness, and uniqueness in everything not just in the product but in marketing as well. One of its unique products is brief for women (as shown in figure 7). The company emphasises maximisation of ‘brand potential and consumer reach’ but remains focused on the true elements and functions of their products (PVH: our company, our strategy 2015 para. 2). Calvin Klein products include shoes and different kinds of international footwear, men and women’s clothes, especially suits for businesses.

Part of strategic positioning is acquisition and joint ventures of legitimate business enterprises from the different areas of the world where they see their core competencies are met.

Calvin Klein is subdivided into two segments, one for North America and the other one for international operations. North America operations have central offices in New York, which supervise control of businesses in the United States and other North American countries. The jurisdiction of Calvin Klein International includes those in Europe, stationed at Amsterdam; Asia, which is primarily based in Hong Kong, and includes operations for Shanghai, parts of China, and Seoul in South Korea; and Latin America, with its base in Sao Paolo, Brazil (PVH: our company, our strategy 2015 para. 2). Organisation and structure of PVH is in Appendix 2.

It is clear that Calvin Klein will continue to adapt strategies of mergers and acquisitions. This strategy of international marketing has become a major part of American business.

While there are successes in mergers and acquisitions (M&A), there have also been disadvantages in this phenomenon. In the twenty-first century, the latest M&A wave quadrupled the 1980s wave, which surpassed all other records for the number and dollar value of corporate M&As. This strategy may create value at the macroeconomic level, but benefits for the shareholders sometimes do not meet expectations (Copeland et al.; Jensen; Ravenscraft & Scherer; Shower; Varaiya & Ferris, cited in Auster & Sirower, 2002).

Merger waves should be understood because ‘they reconfigure industries, fundamentally reshape corporate strategies, transform organizational cultures, and affect the livelihoods of employees’ (Auster & Sirower 2002, p. 216).

Studies found the purposes for M&As: economic reasons, managerial self-interest, and market corporate control (Auster & Sirower 2002). Managers argue that their motives are purely rational and in the best long-term interests of the firm and shareholders. M&As have been seen as a tool for many things, from increasing market share to diversifying products and services; attaining operational elasticity, new knowledge, and personnel; improving innovation and learning; dealing with risks; improving managerial experiences; and streamlining the national economy and ‘increasing global competitiveness’ (Auster & Sirower 2002, p. 218).

There have been a number of empirical research analysing the benefits of M&As, whether this in fact deliver the expected results. Research focusing on the combined gains to the shareholders found positive excess returns, but it is the target firm shareholders who attained this gain (Bradley et al., cited in Auster & Sirower, 2002, p. 218).

In the case of PVH (who owns Calvin Klein), the managers claimed that they acquired positive gains from their M&A activities. However, this is quite contrary to the empirical research found in the literature. Jensen and Ruback (cited in Auster & Sirower, 2002) found positive gains for the acquirer shareholders, but other research that focused on acquirer returns found a reliable flow of negative results focusing on several case studies. The study also found that many M&As destroyed value and provided ‘significant negative performance’ (Agarwal, Jaffe & Mandelkar; Magenheim & Mueller, cited in Auster & Sirower, 2002, p. 219).

The PVH management stands firm in their statement that the company gained from their series of acquisitions and they will continue to conduct acquisitions in the future to improve strategies. This is their strategy and we have to respect it because, as they say, their company was successful with it.

Chanel

Chanel’s success is attributed to its popular little black dress, top-of-the-line clothing and handbags. Chanel has been a reliable source of typical but fashionable luxury goods. Its favourite buys by the brand-craze consumers are the ‘quilted leader envelope clutch’ and the unique ‘cashmere dress,’ a fibre dress whose raw material comes from cashmere goats (Ruiz 2008).