Introduction

Every organization desires to possess a compensation scheme that allows its employees to earn pay that is commensurate with the level of their dedication and performance. In recent times, the concept of pay transparency has been lauded as one way of eliminating disbursement discrimination. The rationale is that if workers know what every other person in a company is earning, patterns of pay discrimination will become evident. Hence, the pressure to address them will increase eventually, thus paving the way to pay equity. However, pay transparency causes more harm than benefit in an organizational situation because most employees already feel that they are performing better relative to their peers. This feeling emerges from the need as humans to exaggerate their performance. Sadly, realizing that any employee who workers feel is perhaps less dedicated earns more will be demoralizing. Hence, as the paper argues, while pay transparency encourages pay equity, it often results in the undesired effect of causing employees to feel underpaid and underappreciated to the extent of further leading to unintended negative outcomes in an organization.

Encourages Employee Dissatisfaction

When designing a compensation scheme, most employers do not factor in employees’ perception of their performance. Incidentally, employees perceive their performance to be better relative to that of their peers. Pay intelligibility avails an expansive autonomy for workers to amplify their performance and input to the company (‘The case against pay transparency’, 2016). As such, it is clear that a company’s management and its employees differ regarding their measure of performance. A sizeable number of employees then will feel underpaid based on what they perceive to be their performance level. Hence, publicizing pay will leave the majority of employees (most of whom possess exaggerated views of their performance) unsatisfied with their current pay. Consequently, such employees will develop negative emotions that will affect their productivity.

Human resource officers in charge of compensation in most organizations have not received proper training on compensation. As such, they cannot be trusted to come up with effective strategies to match pay and performance. At the same time, employees who are suddenly made aware of the existence of pay disparity will approach these managers for an explanation regarding the metrics used to arrive at the various pay grades (Jha, 2013). Such employees get less than satisfactory responses, thus causing them to become frustrated. This frustration is understandable since employees realize that people who understand little about them are determining their salaries. It is common knowledge then that employee dissatisfaction immediately follows. For this reason, pay transparency should be the reserve of organizations that have invested in the proper training of their human resources regarding pay and compensation matching.

Encourages Turnover

Pay transparency encourages a high rate of employee turnover because of the workers’ feeling of being underappreciated based on their current pay. Such turnover may also arise because employees use their salary to determine whether a company values their contribution. Employees who earn less compared to their peers will feel undervalued. As such, they are likely to leave the organization. Card, Mas, Moretti, and Saez (2012) conducted an online survey regarding how employees of the University of California perceived the institution’s decision to make all employees’ pay public. The findings showed how workers were “more likely to leave their job than to ask for a raise in response to learning that they are underpaid” (Card et al., 2012, p. 2996). Consequently, after experiencing a high employee turnover, an organization has to recruit other employees to replace those that have quit their positions. This situation causes the operational costs to rise above the normal budget.

Pay transparency may expose an organization to various disadvantages associated with employee turnover. Particularly, employees who leave an organization due to pay dissatisfaction may end up being hired by competitor firms. In their new positions, they may be forced or even willingly disclose the trading secrets of their former employer (Almeling, 2012). Armed with the secrets, the new employer may proceed to gain an edge in the market to the disadvantage of the former employer. Most organizations strive to protect their secrets from being accessed by competitors. Thus, a high employee turnover due to dissatisfaction caused by pay transparency may thwart such efforts. Additionally, if a company discloses its pay schemes while the competitor firms have not done the same, it opens itself to increased competition because the rivals will not experience the negative outcomes of pay transparency, particularly employee turnover.

Reduces Employee Productivity

Pay transparency causes reduced productivity among employees who feel underpaid. Employees’ dedication to the position is directly influenced by how they perceive their compensation. It emerges that employees who discover they are underpaid may become less dedicated to their work. Using a sports tournament, Obloj and Zenger (2015) examined the motivation of participants based on the level of reward involved for each level of the tournament. Unsurprisingly, participants were far more motivated to the extent of posting better results where the level of reward was more valuable (Obloj & Zenger, 2015). Thus, in a business scenario, pay transparency only makes some employees realize they are working for much less compared to their peers. As a result, they will be tempted to take their work less seriously since they feel the pay is not commensurate to their input. Thus, rather than being a source of motivation, pay transparency ends up discouraging employee dedication.

Employees who suddenly discover they receive less relative their colleagues will be tempted to lobby for better pay. Arguably, the less paid employees will not feel obliged to complain if they are unaware of what their peers take home. However, realizing one is underpaid causes the urge to demand improved pay through worker strikes (McGill, 2016). As a result, workflow in the organization will become disrupted, thus resulting in enormous losses. At the same time, companies may avoid such losses by maintaining confidential pay records. Up to the early 2000s, Harvard University had a cadre of highly paid managers whose hard work earned the institutions billions of dollars annually (‘The case against pay transparency’, 2016). Because this scheme remained largely unknown to the rest of the workforce, it never raised much concern. However, upon making its pay scheme public, students, alumni, and other employees opposed this pay, a situation that led the university to scrap it. Consequently, most of these highly valuable managers left the organization to escape low salaries.

Pay transparency diminishes the employer’s flexibility to use pay as a competitive tool. As seen in the case of Harvard’s managers, an employer could use a high salary as an incentive to attract and retain some high-quality employees (Jha, 2013). Because of their specialized skills, such employees may demand more pay than the company offers for their cadre. Naturally, an organization would be willing to honor such demands, but for the transparent pay scheme. In other words, other employees may protest the decision to overpay a peer, regardless that he or she is more qualified compared to them. In this case, the company has no choice but to let go of a highly-skilled potential employee. Similarly, organizations are willing to pay disproportionally high salaries to the top executives based on their contribution to the business. This reimbursement approach can only be suitable if the other employees are unaware of the huge pay gap between the top management professionals and themselves.

It is against Employees’ Right to Privacy

Many employees are not ready to have their pay disclosed to the public because what one earns is regarded as a top-secret. The Fourth Amendment to the US Constitution guarantees people, including workers, the right not to have information about them disclosed without their consent. Employees are not interested in knowing what their co-workers are earning nor do they wish to have their pay disclosed. Numerous reasons have been established as to why employees want their pay to remain a secret between themselves and their employer. Whether these reasons are valid or not is a non-issue because the right to privacy is paramount. Given this awareness, organizations must only disclose salaries where all employees are comfortable with such a decision. Disclosure of pay favors the highly paid employees in an organization. As such, it is unnecessary for the majority of employees.

Most organizations do not possess the right environment to support or reap the benefits of pay transparency. Pay transparency works best in organizations that have proper mechanisms for monitoring individual performance (Lytle, 2014). Conversely, most companies do not have these mechanisms nor do they possess comprehensive performance records of employees. As a result, the metrics used to set employees’ pay are wanting right from the onset. Similarly, employees and employers view performance appraisal differently. As such, it is difficult to agree on the scale that should be used to achieve fairness. Given this situation, pay transparency cannot result in the desired outcomes unless an organization has taken the necessary steps to address the mechanisms for measuring performance in the first place. It follows then that transparency cannot work effectively in organizations that rely on pay for performance approach to compensation because employees are likely to question the metrics that the organization uses to arrive at a certain pay.

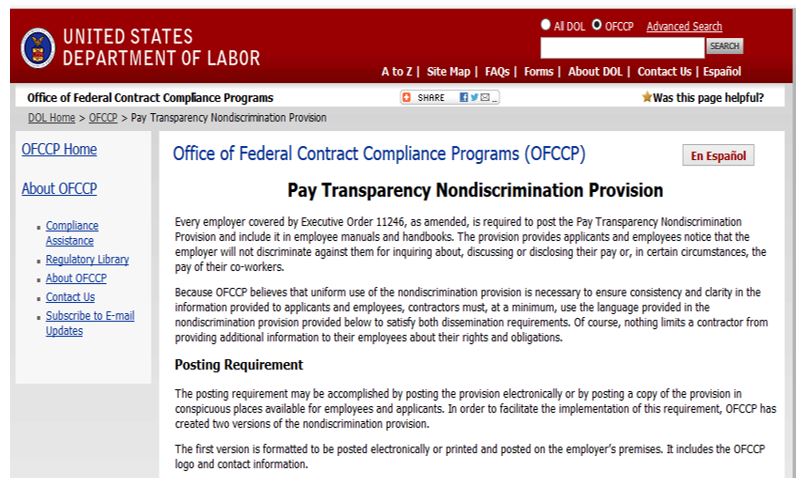

Many organizations are simply not prepared to adjust their performance management systems to handle the pressure accompanying pay disclosure. In the past days, employers were under no pressure to discuss how they arrived at a certain pay for each employee. As shown in Figure 1 in the appendix section, with the recent amendment to Executive Order 11246 by former US President Barack Obama requiring all employers with more than 100 employees to disclose their compensation breakdowns, many organizations realize they are unprepared for the task. This unpreparedness creates disparities between the desired outcomes of the pay disclosure policies and the actual results. For instance, the management departments of most companies find themselves unable to demonstrate why some employees earn more relative to others. This inconvenience affects both the confidence of the management and the morale of employees who suddenly discover they are underpaid. At the same time, being unable to justify their performance metrics does not necessarily imply they are unjustified because some metrics used are simply subjective. As such, they should not be judged using the objective threshold established in laws such as the president’s executive order.

Lack of a Positive Attitude toward Competition

The effectiveness of pay transparency is subject to the existence of a positive competitive culture in an organization whereby employees are likely to view high salaries for some peers as a motivation to work harder. However, this situation is hardly ever the case because employees in most organizations do not possess a positive attitude toward competition. Similarly, paying some employees more than others is treated as favoritism. Hence, it is frowned upon. From this observation, it emerges that a positive culture towards competition is more important compared to pay transparency. As such, rather than investing in pay transparency, organizations should strive to develop a culture of competitiveness among their employees.

Pay transparency discourages aggressiveness by employees by promoting flattened pay. Organizations that embrace pay transparency are forced to flatten their reimbursement schemes after realizing that employees are dissatisfied with the metrics of performance appraisal. The practice works best where performance pay is not utilized. Instead, companies adopt more subjective metrics for setting salary, for example, seniority and position. While such a move prevents dissatisfaction by employees, it results in laziness since no incentives are availed to reward hard work. In other words, employees’ motivation to work hard reduces. As a result, the most capable employees will leave the organization for more challenging and rewarding environments. Thus, instead of promoting competitiveness, pay transparency results in the exact opposite outcome.

Pay transparency may force an organization to take drastic measures that inadvertently limit the overall intelligibility in the organization. In diminishing the instances where the less paid employees complain about pay discrimination, an organization may be tempted to physically separate groups of employees (Card et al., 2012). This move would mean reduced contact between the less paid employees and their highly paid counterparts. While such a move causes the complaints about pay inequity to subside, it will cause a breakdown in communication and workflow. Effective communication and workflow are necessary for driving organizational success. In their absence, the overall performance of the organization will decline. This outcome is undesired since pay transparency is performed primarily to boost productivity.

Counter-Argument

Notwithstanding, proponents such as Saari (2013) argue that pay transparency discourages negative corporate practices, including gender discrimination. For a long time, companies have treated women differently compared to men based on their sex rather than their capabilities. Similarly, McGill (2016) asserts, “companies that promoted pay transparency reduced gender wage gaps and various other forms of salary discrimination” (p. 23). Today, feminists recognize the need for organizations to post their salary metrics publicly as a major approach to eliminating gender discrimination. According to Saari (2013), pay transparency forces companies to treat their female employees the same as the male employees. However, effective methods of dealing with gender discrimination in the workplace are available, for instance, an effective strategy for a promotion that relies on merit without undue regard to the employees’ sex. Such an approach would be more effective compared to simply setting a flat salary for every employee with the hope to eliminate gender disparity in pay.

Pay transparency is not an effective approach to addressing gender discrimination in the workplace because worse forms of gender discrimination (than pay inequality), which exist in the workplace, cannot be rectified simply through eliminating pay secrecy. For instance, sexual harassment of female employees is a more serious concern for many women relative to what their male colleagues could be earning. Shockingly, sexual harassment remains prevalent even in organizations that have adopted pay transparency (Saari, 2013). This finding is a clear indication that pay transparency cannot be an effective tool for combating prejudice against women in the workplace. Instead, organizations should adopt a thorough anti-harassment policy coupled with a culture that encourages respect for women first. Hence, pay transparency should not be the primary approach to eliminating gender disparity in the office simply because it will fail if not supported by a strong culture of respecting women.

Racism and gender discrimination often demonstrate themselves in aspects such as employees’ salaries. Proponents believe that pay transparency can eliminate systemic racism in an organization. While it is important for employers to ensure pay equity, regardless its employees’ ethnicities, pay transparency only seeks to address the symptoms rather than the cause of the problem. Federal departments with transparent pay schemes often record instances of racism, an indication that a deeper problem than pay equity exists. In other words, racism cannot disappear from a company because all employees earn equal pay. Instead, every well-meaning organization must devise robust mechanisms for confronting racist tendencies such as unfair targeting of minority employees. If organizations can achieve these mechanisms, equity in pay will be automatic whether pay records are publicized or remain as a private issue.

Pay transparency is believed to increase trust between the management and the employees in an organization. True, some employees may find the information about what their colleagues are earning valuable. As Obloj and Zenger (2015) opine, if employees are aware of what their colleagues earn, they do not spend much time worrying about whether they are receiving justified pay. However, employees who need to see their peers’ paycheck for them to be committed to the organization are simply not worth hiring in the first place. Every organization must seek to work with only dedicated employees whose primary concern is not how much they are earning relative to their colleagues. Indeed, employees who love their work do not usually spend much time worrying about the pay. Thus, organizations should primarily concern themselves with evaluating the dedication of such employees and not the pay culture. Employees who are dissatisfied with their pay are more likely to leave the organization than to demand to know what other workers are earning.

Pay transparency is believed to enforce equality in organizations. However, the notion of equality may be hard to enforce since employees are gifted differently. In other words, some employees demonstrate exceptional skills in certain areas, which simply warrants them to earn more. Given this situation, equal pay is simply impossible to realize for an organization that values the individual input of every employee. Instead, organizations should strive to achieve pay equity where employees earn according to their performance. Equity in pay can be enforced by involving all employees in creating an effective formula for evaluating performance. This approach would ensure they are comfortable with the pay they receive. Most employees are dissatisfied with pay because they are not involved in the establishment of their performance appraisals. Hence, they feel cheated. Pay transparency is suitable for organizations with a small number of employees. However, they do not work properly in large organizations where the employees do not even know each other. As such, the benefits ascribed to the practice cannot be realized in large organizations.

Some proponents such as Lytle (2014) believe the exact opposite. According to them, pay transparency helps to reduce employee turnover in an organization. This notion originates from the assertion that employees who are aware of what their colleagues earn are less likely to feel cheated in their pay. Sadly, while this belief could hold some truth, it fails to appreciate that most organizations do not have proper metrics for determining salaries. For this reason, publishing employees’ salaries will only cause dissatisfaction with the existing methods used in setting the pay. Unfortunately, rather than reducing employee turnover, it drives them away due to the frustrations. Thus, the notion that pay transparency assists in employee retention are simply untrue.

Other supporters of pay transparency such as the United States Department of Labor (2016) argue that the practice rewards high-earning workers while motivating their low-earning counterparts to work harder for better pay in the future. While this argument may bear some truth, for most employees, pay transparency only sparks discontent and feelings of little self-worth. High-earning employees such as top executives welcome pay transparency because it presents them as being able and dedicated. Thus, while it favors the top-notch employees, it is of little use for the lower-ranking workers who are otherwise comfortable without such knowledge. Therefore, pay transparency is an unnecessary practice with little or no benefit to the majority of an organization’s workforce.

Obloj and Zenger (2015) argue that pay transparency encourages promotion due to increased employee productivity. However, while this practice has become a norm in the private sector, little can be shown in terms of employee promotion based on productivity. As such, pay transparency has had an insignificant positive impact on the public sector. Many federal/state departments and institutions already have a pay transparency policy in place. At the same time, these institutions do not register any better results relative to the private organizations, most of which do not publish the salaries of their employees. Public institutions post worse promotion patterns relative to their private counterparts. For these reasons, one cannot help but question the viability of transparent salaries as a policy.

Conclusion

Recently, former US President Barack Obama issued a directive for all medium to large organizations to release their salary records to the public. The move was lauded as a major step toward combating gender discrimination and racism in offices. Before then, organizations such as Whole Foods Market Inc. and the University of California already had similar measures in place. Despite a strong belief existing to the effect that pays transparency boosted employee satisfaction, the paper argues against it because it does considerable harm to organizations. One of the major harms is that of causing dissatisfaction after employees discover the existence of pay inequality. Overall, the disadvantages of pay transparency far outweigh its advantages. As such, no organization should feel obliged to adopt it. Unlike popular belief, there is little evidence to show that it motivates human resources to work harder to earn better salaries. Conversely, overwhelming evidence indicates that employees only become jealous and discontented upon realizing that they are underpaid compared to their peers.

References

Almeling, D. S. (2012). Seven reasons why trade secrets are increasingly important. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 27(1), 1091-1117.

Card, D., Mas, A., Moretti, E., & Saez, E. (2012). Inequality at work: The effect of peer salaries on job satisfaction. The American Economic Review, 102(6), 2981-3003.

Jha, A. K. (2013). Time to get serious about pay for performance. JAMA, 309(4), 347-348.

Lytle, T. (2014). Making pay public. HR Magazine, 59(9), 24-30.

McGill, J. (2016). Is pay transparency good for business? NZ Business, 30(10), 23-24.

Obloj, T., & Zenger, T. (2015). Incentives, social comparison costs, and the proximity of envy’s object. Web.

Saari, M. (2013). Promoting gender equality without a gender perspective: Problem representations of equal pay in Finland. Gender, Work & Organization, 20(1), 36-55.

‘The case against pay transparency’ (2016). Harvard Business Review. Web.

United States Department of Labor. (2016). Office of federal contract compliance programs (OFCCP) – pay transparency nondiscrimination provision. Web.

Appendix

Source: (United States Department of Labor, 2016)