Introduction

Background to this study

The World Tourism Organization (WTO) predicted that China will become the world’s number one tourist destination by the year 2020 and will generate approximately 130 million tourists per year (1999). Furthermore, The World Tourism &Travel Council (WTTC) predicted that Travel & Tourism Demand of China will keep increasing 9.2 % annually from 2006 to 2015 which represents a growth of 305,554.0 million U.S. dollar per year (2005). The Travel and Tourism contributes is expected to contribute 9.2% (US$499.9bn) to China’s GDP in 2010 and will remain an average 9% for the following 10 years (WTTC, 2010).

The demand for travel and tourism creates a great opportunity for China’s hotel industry. The Ministry of Commerce released that in the first quarter of 2008 369.73 billion Yuan in sales occurred in the hospitality sector (“Hospitality”, 2008). In fact, the hotel industry started to develop rapidly since 1978, owing to the implementation of the open-door policy and economic reforms (Chan & Xu, 2010), which enabled China’s hotel industry to develop to international standards by importing superior management skills and foreign investment (Kong & Cheung, 2009).

In China, although foreign investment is encouraged and supported both politically and financially, it is still under the control of the government (Pine & Qi, 2004). However, since China joined The World Trade Organization (WTO) in2001; it effectively lost some control and encouraged more foreign hotel chains to expand in China (Kong & Cheung, 2009). Now around 10% of the world’s top 300 hotel corporate chains have entered China such as the Hyatt, Shangri-la, Marriott, Accor, Starwood and Hilton. These brands, in China, are mainly present in the upscale category, rated as four- or five-star hotels (Pine &Qi, 2004). As indicated by Chan and Xu (2010) Chinese hotel guests now tend to rely more on brand equity when selecting hotels, it is considered to be a promise of service quality that they can expect. Meanwhile, foreign-invested brand hotels perform better than others, in both occupancy rate and average yearly revenue per room (Pine &Qi, 2004).

Justification of the study

A number of previous researches have examined customer perception and brand equity, but only a fewer of them are linked to the customer’s choice of hotel. None of them apply these concepts specifically to China’s hotel industry. Thus this research study is designed to fill the research gap by investigating the importance of brand equity in China’s hotel industry and identifying the relationship between the Chinese perception of brand equity and its influence on their selection of hotels in China. The author will attempt to provide some constructive suggestions to hotels in China for their future brand strategic management from this research study. Along with the impact on the hotel industry of China entering the WTO, many international hotel management companies changed their expanding strategy from management contracts to franchising which created a hotel franchising trend in China in recent years (Pine, Zhang, & Qi, 2000). Through this research study, some helpful recommendations will be made by the author for potential franchisors in China when making their franchising decisions on certain hotel brands.

Aims and Objectives

The aim of this research study is to analyze the impact of brand equity on Chinese customers when they select hotels in China. The main objectives are:

- To critically review the relevant literature on brand equity, customer’s perception on it, how it influences consumer behavior and the brand effect in China.

- To analysis the Chinese customers’ perceptions of hotel brand equity and how it affects them when selecting hotels in China.

- To investigate the importance of brand equity in China’s hotel industry during recent years, and develop some recommendations for hoteliers in China on future brand management and also for some potential hotel franchisors on future franchising decision-making.

Research Questions

- Does brand equity and customers’ perception influence consumer behavior, and what effect does this have on brand China?

- What is the perceptions of Chinese customers regarding brand equity, and how does this impact on their selection of hotels?

- How important is brand equity in China’s hotel industry?

Hypotheses

Hypothesis 1

- HA: Brand equity and customers’ perception influence consumer behavior in the choice of brand China.

- Ho: Brand equity and customers’ perception do not influence consumer behavior in the choice of brand China.

Hypothesis 2

- HA: The perception of Chinese customers on brand equity has an impact on their choice of hotels

- Ho: The perception of Chinese customers on brand equity does not impact on their choice of hotels

Structure of the Research Study

This research study contains five major chapters. In order to assist readers to better understand the structure of this study, a summary of each chapter is offered below.

Introduction to the Study

This chapter will give a general introduction to this research paper, including the research background and the justification of the study. Moreover, it will also summarize the aims and objectives of the study, and give a short explanation of the structure of the study.

Literature Review

In this chapter, the secondary literature will be examined on various concepts in the field of brand equity, the interrelation of brand equity, customer’s perception of brand equity, and the brand effect in China. Furthermore, the gaps between existing literature and further research will be discussed, to support this research and the primary data collection.

Methodology

In this chapter, the author will indentify the research design that is used in this research study, including the research philosophy, research approach and research strategy. Then the sampling method of this study will be explained. After that, the design of the questionnaires consisting of writing translations and validity and reliability testing will be explained. Moreover, in this chapter the data collect and analysis method and research ethics will be provided at the conclusion.

Result

In this chapter, the primary data collected by the questionnaires will be analyzed and linked to the gaps that one listed in the second chapter. The results from the data collection process will be well presented and somekey findings will be deduced to conclude this chapter.

Conclusion

Lastly, in this chapter conclusions and recommendation that based on the research results and the literature review will be stated. Additionally, self-reflections and some limitations of this research will be indicated at end of this study.

Literature Review

Introduction

This chapter examines the existing literature, giving a clear and brief idea of thetopic of brand equity to the reader. The chapter starts in Section 2.2 with an overview of the relevant literature about brand equity, especially focusing on customer-based brand equity. The available research on the factors affecting customers selecting hotels will be examined as well. The review will synthesize literature on brand influence in China’s hotel industry and how they affect Chinese’s selection of hotels in China, in order to make some constructive suggestions for hotels’management team and future potential franchises. Finally, the review will provide an investigation of the relationship between brand equity and customer choice.

Brand effect in China

A brand

China has implemented the open and reform policies since 1978 for the purpose of changing the economy to be market oriented and attract more foreign investment to China (Kong & Cheung, 2009). Under the influence of that policy, China’s hotel industry has been developing with government assistance. Moreover, according to the hot globalization trend in the hotel industry and China’s encouraging and favourable policy for foreign investment, various international hotel groups were launched in China in the last decade, such as Holiday Inn, Sheraton, Hilton and Shangri-la (Pine, Zhang, & Qi, 2000). These brands present an image of high category (four- and five-star) hotels in the Chinese mind (Pine & Qi, 2004). As foreign branded hotels, they seem to attesta higher expectations and perceived quality from the Chinese market, significantly impacts brand loyalty and the satisfaction of Chinese consumers (Ha, Janda& Park, 2009).

The Chinese perception of brand and value is considered to be highly affected by global trends and western culture (Wang, Vela & Tyler, 2008). As a result, overseas-invested hotels receive higher preferences from Chinese customers than others and they are more able to charge a high room rate (Pine & Qi, 2004). In Pine, Zhang and Qi (2000) it was argued that China’s hotels and as Chinese consumers are still heavily influenced by foreign tourists. Accordingly, those foreign hotel brands are considered more acceptable “home” brands, and are welcomed and appreciated in the Chinese market. Influenced by the rapid economic growth in China, incomeshave varied and a huge gap has been created between rich and poor (Wang, Vela & Tyler, 2008). The newly created rich are more likely to pay for international branded hotels, since these hotels are indicators of upper-class social groups. Wealthy Chinese want to belong to that group, and accordingly, are distinguished though choosing higher category hotels from groups that can’t afford it. In that regard, “brands are used to distinguish oneself from the social group one does not belong to and brands communicate the membership of one’s own group (TANG, 2007, p. 253).

Describing the Chinese consumer today, Tang (2007) argues that Chinese consumers are more focused on the aesthetics and social values of a product/service than on their basic needs.As a result, branding can be seen as a significant element in the new Chinese society. Tang (2007) also suggested that strong brand information has a significant and positive impact on influencing Chinese consumers’ decision making.

Brand Equity

The concept of brand equity emerged in the 1980’s, and became the main topic of interest for researchers in marketing literature (Aaker& Biel, 1993). Brand equity was defined by David Aaker, whose book Managing Brand Equity, popularised the concept, as “a set of brand assets and liabilities linked to a brand, its name and symbol that add or subtract from the value provided by a product or service to a firm and/or to that firm’s customers” (Aaker, 1991, p. 15). Brand equity is the most valuable asset of the firm. Moreover, it shifted the focus from price as the primary competitor, since strong brands can offset the huge pressure on price (Aaker& Biel, 1993). As a result, brand equity can assist a property to be able to charge more for similar categories of products or services than competitors. In China, for example, a bottle of beer costs double in a lounge of an international hotel than a local hotel and people are still happy and willing to pay such high prices. Ogaba and Tan (2009) indicated that a strong brand, with high equity, will attract a large number of committed customers, as it will create a stable and continuous bridge between the brand and its customer, and it can shape customers’ beliefs to fit the brand. The latter indicates that brand equity can heavily influence consumers’ behaviour, and accordingly, the decision making process.This will be discussed later in this paper.

Brand Equity in the Hotel industry

The hotel industry is considered as a representative example of the service industry, and brand equity is vital to itssuccess (Chan &Xu, 2010). Moreover, as one of the core products of the hotel industry is service, Keller (2002) pointed out that the only thing hotel guests have after they leave is the memories of their experience. Thus, to make this intangible experiencetangible is a challenge for the hotel industry, and it can only be done by creating strong brand equity (Arasli&Kayaman, 2007). As Brand equity provides a general idea of hotels for customers so they can evaluate the hotel based on this information. Furthermore, brand equity can assist customers to interpret hotels and generate information on the brand, in order to make customers confident in the purchase decision (Aaker, 1991). In the hotel industry, strong brand equity enables customers to better understand the intangible side of the hotel products and services (Tolba& Hassan, 2009). For example, with information about the perceived quality and brand awareness sides of brand equity, it can make customers to have a general idea of the hotel image and the service standard. Under the influence of strong brand equity, customers are able to obtain more brand information to make their purchase choice. Brand equity can also lead customers to choose specific brands as a strong brand equity can be seen as a promise of service which provides confidence (Chan &Xu, 2010). Finally, according to the research of Kim and Kim (2005) on luxury hotels and chain restaurants, strong brand equity is good for charging a premium price, reducing costs and increasing revenue in the hospitality sector.

Brand Equity from the Perception of Customers

Keller (1993) indicated that it is important to understand brand equity from the customer’s side, since the positive impact of brand equity on customers can assist organization to raise revenue, reduce costs, and increase profits. Keller also stated that brand equity has various effects on customers’ brand knowledge, which affects the brand’s marketing (2000). In that regard, Keller and Lehmann (2003) introduced the concept of customers’ mindset measure, that is, everything in the customers’ mind including their thoughts, images, feelings, perceptions, beliefs, which are linked to a brand. Such a concept covers a wide range of both qualitative and quantitative measures of band equity. Thus, it can be stated that the way brand equity influences customers is significant and it is essential to understand how customer perceive brands.

As supported by a study done by Keller (1993), under the same marketing activities, a branded product/service is more easily appreciated and accordingly generates more positive brand equity from customers’ perception than a similar unbranded one. And the So & King (2010) suggested brand equity canbe used to explain the changes in sales that occur due to customers’ brand knowledge, and which are affected by the marketing activities of a firm. Moreover, as indicated in Biel (1992), customers’ perception of a brand, has a significant impact on customers’ behaviour. The perception affects the value of brand equity in the customers’ mind, and in turn, influences buying preferences and decisions. Wang, Wei, and Yu (2008) thought that customer-based brand equity was founded on the customers’ confidence and belief in certain brands.Such confidence and belief leads to customer loyalty and the willingness to pay a premium price. As stated in Erdem et al. (1999), brand equity is tightly linked to the customers, where customers’ perceptions of brand equity dynamically influence their choices, preferences and decisions.

The above indicates, the importance of brand equity in today’s marketplace, and customer-based brand equity is attractive for researchers and market participants. Numerous definitionsenlist on brand equity in the marketing literature, however, one aspect these definitions have in common, is the notion that the value of a brand is based on the brand’s effect on customers (Erdem et al., 1999). Aaker (1991) and Keller (1993) conceptualized brand equity fromthe consumers’ perspective, where the resulted concept is referred to as customer-based brand equity (CBBE). This concept was defined by Aaker as “the value consumers associate with brand, as reflected in the dimensions of brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality and brand loyalty” (1991, p.15). Referring to Aaker (2002), customer-based brand equity is divided into 4 major dimensions that form the customers’perceptions; they are brand awareness, brand loyalty, perceived quality, and brand image. On the other hand, Keller (1993) held a different opinion, as he enhanced the importance of brand knowledge in terms of brand awareness and brand image, and suggested to there had a significant effect on consumers. In this study, the author holds the same views as Aaker and the four dimensions (Aaker, 2002). In the following sections, these four dimensions will be examined into more detail.

The Four dimensions of Customer Based Brand Equity:

Brand Awareness

Brand awareness was defined by Ross (2006) as the strength of a brand, that existed in the consumer’s mind and it is a vital part of brand equity, conceptualizing the construct for both product and service (Keller, 1993, Kayaman & Arasli, 2007). With brand awareness, the brand enables the potential buyer/customer to recognize or recall a brand in a product/service category (Laverie, Wilcox, Kolyesnikova, Duhan& Dodd, 2008). Customers can be affected in their further buying preferences and decision making processes, by the three advantages brought by awareness. The advantages are learning, consideration and choice advantage (Keller, 2003). As suggested by Lockshin and Spawton (2001), such awareness is a necessary condition for creating a brand preference/disliking, brand loyalty and brand familiarity. Also, brand awareness has a significant impact on building brand equity and serving as an instruction for enhancing customer-based brand equity and formulating the brand’s strategy approach (Wang, Wei & Yu, 2008). Same as above – connect the different topics

Brand Loyalty

The influence of brand loyalty can be seen as broad, where its influence expands beyond customers who continuously buy a service or a product of certain brand (Keller, 1998). Aaker (1991) stated that brand loyalty is an extremely important component of brand equity. Aaker argued that brand loyalty cannot exist without the previous buying experience, and the loyalty of these existing customers will qualify a firm with a competitive advantage to build an entry barrier for competitors. These loyal customers will enable the firm to attract more new customers, creating a positive and effective message to potential customers (Aaker, 1991). According to the aforementioned, the strong brand equity will enable a firm to expand more widely and successfully. Furthermore, brand loyalty also acts as an essential part of brand equity, while brand association is the reason-to-buy a service or product from the customer’s point of view (Aaker, 1991).

Brand Image

Brand image is a set of brand associations which are similar in concept (Laverie, Wilcox, Kolyesnikova, Duhan& Dodd, 2008). Additionally, it can be stated that brand image drives brand equity (Biel, 1993), where it is considered to the customers’ perceptions which are linked to a specific brand (Koubaa, 2008). Thus, the Four Season Hotels could be linked to a particular consumer segment, which is the upscale market, and evoke a particular feeling such as luxury/enjoyable. Brand image is the outcome of psychological configuration and analysis, where both internal and external factors have a remarkable impact. The internal factors can be explained as the personal characteristics of consumers and are considered more important to the brand image of the customer-based brand equity (Koubaa, 2006). Customer perception of brand image can distinctly influence consumer behaviour. Brand image can give customers a specific reason to select a brand, based on the associations delivered by such a brand (Ataman &Ulengin, 2003). Additionally, Ataman and Ulengin (2003) also indicated that customers might be influenced to buy a certain brand, for the purpose of improving their self-image.

Perceived Quality

In order to understand perceived quality, two aspects should be clearly distinguished, physical quality and perceived quality. Although physical quality is important, it does not necessarily directly affect brand equity. However the perceived quality does, (Anselmsson, Johansson & Persson, 2007). Perceived quality differs in terms of the satisfaction that customers’ receive through intangible aspects of a product, and the overall feelings about a product/service in the customer’s mind (Aaker, 1991).Perceived quality provides value to customers’ purchasing decision by providing them with a buying reason and distinguishing the brands, one from the other (Arasli&Kayaman, 2007). It can be stated that perceived quality has a direct impact on profitability and return on investment (Aaker, 1996). Moreover, a positive perceived quality can enable a firm to set a premium price, in order to be more competitive and bring more profit (Aaker, 1991).

The relationship between brand equity and its four dimensions

A relationship exists with the brand equity dimensions outlined previously, thus it can be concluded that these dimensions are not independent. Grouping the dimensions into two components, that is association and awareness, characterizes brand knowledge, as stated by Keller (2003). Therefore, it can be stated that the strength of both the association and the awareness leads tostronger brand equity in general. Accordingly, spreading the aforementioned components over the four dimensions identified by Aaker, that is perceived quality, brand awareness, brand loyalty, and brand association, it can be seen that such relation persists. Aaker (1991) suggested that perceived quality influence brand equity through the creation of the brand’s value.

The influence of perceived quality stems from such attributes as perceived value and brand attitude, leading to the formation of brand image (Aaker& Biel, 1993, p. 145). Brand image on the other hand, can be directly related to the dimension of brand association, where the associations arelinked to form the image. Transcending such relationships between perceived quality, brand image and brand associations, it can be stated that quality is an important dimension.The higher the quality perceived, the more positive the association created for the brand’s image and the stronger is the equity of the brand.

Linking quality perception to the hotel industry, the model demonstrated in Cobb-Walgren et al. (1995) can be used to explain the consequences of the formation of brand perception and accordingly its preference through a comparison between Holiday Inn and Howard Johnson. In that regard, the physical and the psychological features forming the brand perception in such a model can be linked to the dimensions of perceived quality and brand associations. The strength of brand equity in the analyzed hotels was positively correlated with consumers’ preferences, and consequently on their intention for purchase (Cobb-Walgren, Ruble, & Donthu, 1995).

The dimension of brand loyalty is also directly related to brand equity, where unlike other dimensions; it implies an existent experience of customers with the brand. Logically, the correlation between brand loyalty and brand equity is apparent, as the more loyal a customer is to brand the more equity the brand has. This relationship can be explained in that loyalty implies regular purchases by consumers, preventing switching to another brand, and thus, “to the extent that consumers are loyal to the brand, brand equity will increase” (Yoo, Donthu, & Lee, 2000, p. 197). A method of measurements developed byYoo and Donthu (2001) took the concept of Aaker’s dimensions of brand equity, leading to a multidimensional consumer-based brand equity scale (MBE). MBE was calculated as the sum of the mean of the dimensions, among which brand loyalty was one of the constructs, adapted from Beatty and Kahle’s (1988) brand loyalty items (Yoo & Donthu, 2001). Accordingly, in terms of hierarchy, it was argued in Levidge and Steiner (1961), cited in Yoo and Donthu (2001), that brand loyalty is the last in such hierarchy, preceded by brand awareness, brand association and perceived quality. In that regard, considering the importance of experience in forming brand loyalty, such hierarchy can be understood. An example can be seen through the statement that “[p]erception of high product quality leads to brand loyalty because it is the basis of consumer satisfaction” (Yoo & Donthu, 2001, p. 12).

In the hospitality industry the aforementioned aspects can be reflected through such financial indicator as RevPAR, where in Kim, Kim, and an (2003) examined the influence of brand equity and its dimensions on the financial performance of 12 luxury hotels. The study found a direct correlation of all brand equity dimensions on the financial performance of the studied businesses (Kim, Kim, & An, 2003, p. 346). An interesting finding was in the absence of the significant correlation between perceived quality and financial performance, which being a component of the brand image might imply a direction for future researches for clarification.

Gap knowledge

It can be summarized form the literature review that brand equity is an important concept, which is utilized to shape the preferences of customers. With changes in the Chinese perception of brand, to match the western culture, it is interesting to see howcustomers prioritize brand equity dimensions. It can be stated that the literature focuses more on the overall score of brand equity, connecting such score with the performance of the business. In that regard, the literature lacks an independent measure for each of extraneous factors of the dimensions and their influence. Accordingly, the review shows a gap in the measurement of the interconnection between the four dimensions, and the differences in each dimension’s contribution to equity. The questions that might be derived from the review can be seen as:

- To measure the importance of brand equity in China’s hotel industry and figure out whether the perception of Chinese customers on brand equity has an impact on their choices of hotels in China

- Examining which dimension of brand equity has more impact on Chinese customer’s decision when selecting a hotel in China

- Evaluating the influence of each dimension of brand equity on hotel selection in China

Methodology

Introduction to Methodology

This chapter, details of the research design implemented in this study including the research philosophy, approach and strategy.The sampling of this study will be used to explain the data collection process. Then a clear explanation of the design of the questionnaire used in this study will be given.The writing translation and validity and pilot testing will be discussed to assist the reader to a better understanding of this part. Moreover, data analyzes and the research ethic will be examined. Finally a short summary and closure will be introduced.

Research Design

The purpose of this research is to investigate the impact of brand equity on selecting hotels in China. Moreover, this research will measure the importance of brand equity to customers, the influence of its four dimensions as well as evaluate which dimension has more impact. For this research paper, the author selected to a quantitative data collection method to obtain the primary data.

Research Philosophy

The research philosophy is how the author perceives the development of knowledge in a research (Saunders et al., 2007). Choosing the right philosophy is an essential key to theresearch, since it influences the direction of further research. The philosophy used in this study was interpretivism. As stated by Saunders et al. (2007) “Interpretivism is an epistemology that advocates that it is necessary for the researcher to understand difference between humans in our role as social actors” (p. 106). They also suggest that this philosophy is suitable for business and management research, and it can assist the researcher to better understand participants’ perceptions.

Research Approach

For this study, the deductive approach was applied, and a hypothesis will be investigated by analyzing the correlation between variables of brand equity and customer hotel selection (Clark, Riley, Wilkie & Wood, 1998). The deductive approach usually emphasizes on the collection of quantitative data (Saunders et al., 2007).Furthermore, by using the deductive approach, the research cangeneralize the common factors in human behaviors that are measured quantitatively (Saunders et al., 2007). In this study, the population size will be all Chinese, who are able to connect the internet since the online survey was used for the data collection. As the population size is 384 million, 384 responses are required for this research in order to keep the margin of error at 5% and the correctness of the data (Tait, 2010 & Saunders et al., 2007).

Research Strategy

As survey strategy was used in this study in the form of a questionnaire. Saunders et al. (2009) stated that a survey strategy is usually associated with the deductive approach. Furthermore, a survey strategy such as questionnaires enables the author to have control over the research process and generates a large amount of data from the population in an effective and low cost manner (Saunders et al., 2007). The quantitative data will be used to propose possible reasons for the relationship between variables (Saunders et al., 2007). However, there are some limitations of this approach, as it prevents the author, from finding further options of the respondents as it does not cover a wide range (Saunders et al., 2009). Thus, after the questionnaire is designed, translated, tested and approved it will be delivered as internet-mediated questionnaires for the purpose of reaching more people.

Sampling

As defined by O’Leary (2005), “Sampling: The process of selecting elements of a population for inclusion in a research study” (p.87). As this study will examine the impact of brand equity on selecting hotels in China within a limited time period, the author chose sampling to be suitable technique. This is supported by Saunders et al. (2007) that “ sampling techniques provide a range of methods that enable you to reduce the amount of data you need to collect by considering only data from a subgroup rather than all possible cases or elements” (P.204). Since the primary data was collected using internet-mediated questionnaires the total population is not known and thus, non-probability samples techniques was be applied. This is the most practical method for thisresearch projects and pilot survey in at the exploratory stage and it will enrich the information in the case (Saunders et al., 2007). Although the population of an online survey is hard to define, it is still considered as a valuable method to collect information (Lohmann&Schmucker, 2009). The questionnaire will be delivered only to Chinese, according to the objective of this study, so as to find out the Chinese perception of brand equity and how it affects their hotel selection choice.

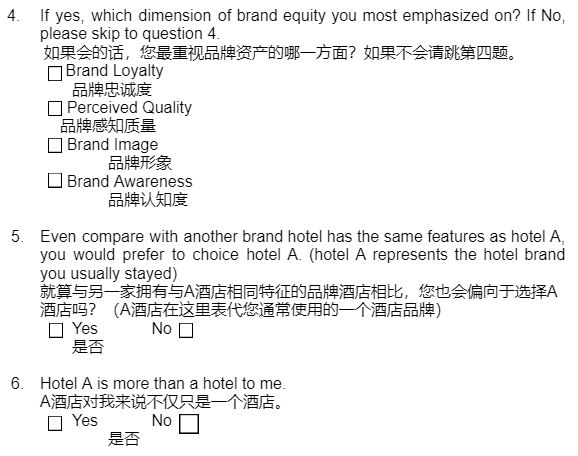

Design of questionnaire

Janes (1999) pointed out that“once you have got the questions written, you need to put together the questionnaire or instrument you are going to use to administer the questions to your subjects” (P.323). It is necessary to design a questionnaireconsistent with the literature review and investigate the hypotheses (Finn et al., 2000). All questions are closed questions, since the questionnaires will be delivered online and if it is too complex will be difficult to analyze the data. In the first section of the questionnaires is a set of questions about the respondent’s personal information. The second section will include some general questions to find out the Chinese’ perception of brand equity and will they choice hotels based on these perceptions. The questions become more detailed in the third section in order to obtain in-depth information about the four dimensions of brand equity and Chinese hotel selection in China. The rating for each respondent to choose their answer from ranges from 1 to 5 and the represented meaning of the number is kept in consistent to avoid respondents’ misunderstanding, which stands for strongly agree (1), agree (2), neutral (3), disagree (4) and strongly disagree (5). To mix ranking and fixed-alternative questions together will assist the author to better understand and analyze the respondents’ options.

Question writing translation

The questionnaires will be in both English and Simplified Chinese. Because Simplified Chinese is the official and widest used language in China. Using both languages avoids participants misunderstanding the meaning of the questions. Initially, the questionnaires is first designed in English then proofed by native speaker to ensure the accuracy. Then, as indicated, the questions will be translated based on experiential meaning, which is “the equivalence of meaning of words and sentences for people in their everyday experiences” (Saunders et al, 2007). Both lexical and idiomatic meanings were also taken into consideration for accuracy. For the Chinese translation, a specialist in both the Chinese and English language will be invited to the double check the questions in order to minimize misunderstandings between the two languages and optimize the final questionnaires (Saunders et al, 2007).

Validity and Reliability testing

A validity test is used to ensure that the questionnaires measure what the author intended to investigate (Saunders et al., 2007). The content, criterion-related, construct validity is normally tested to measure the correctness of the design of the questions and enables the author to secure the expected result based on these questions. Considering the different perceptions of different participants, interpretations could still vary regardless of the correctness of the questions. Saunders et al. suggest that a pilot test should be implemented to improve the questionnaires and minimize misunderstandings of the questions, in order to avoid wrong answers. Moreover, the reliability of the questionnaire is concerned with the consistencyfrom one measurement to the next (Clark et al., 1998). The pilot test was also used to testreliability. Initially the author’s advisor was invited to approve the questionnaires and then five individuals were randomly selected to do the pilot test. The results of the pilot test showed that all the questionsaccurately measured the concept and use reliable.

Data collection and Data analysis:

The questionnaires designed by the author to collect primary data focused on hotel brand equity and Chinese perceptions. This questionnaire will be posted on the website. The author will select some people, and kindly asked them to forward the questionnaires to their friends for the purpose of getting more responses. After gathering the data, the author will use the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) which isavailable in the University Center Cesar Ritz, to analyze and interpreted the data. The data was convertedinto tables and graphs by the SPSS, and it showed the various options and attitudes of participants towards the influence of brand equity in China.

Research ethics

Saunders et al. (2007) suggested that research ethics should be taking into consideration throughout the whole research process and related to each step of the research. According to Clark et al. (1998), “At undergraduate level, the kinds of research undertaken will not usually raise too many ethical issues of the kind where only partial truth-telling is necessary to maintain the integrity of the research program” (p.44). The author was ethical during the process of writing this research paper. Firstly, all secondary data used in this study were selected from academic sources related to the research topic. Plagiarism was avoided when using secondary data and references were clearly made for every sources that used by the author. Secondly, during the primary data collection process, the purpose of this study was clearly explained to all participants in a cover letter attached to the first page of the questionnaire. Furthermoreprivacy and confidentiality of the data were promised by the authorand they will only be used for academic purpose. Lastly in the data analysis process, no fabrication will be added to the original data. During this process, the names of the participants will not be used to ensure confidentiality.

Results

Introduction

In the following chapter, the author will analysis the primary data that collected by the online survey questionnaires. It will start with a short discussion about the reliability of this study. Then, general information of the respondents is going to be investigated which links to the analysis of the demographics of this study. Right after that, the collected primary data will be used to evaluate the general impact of brand equity on Chinese customers’ choices, the specify influence of each dimensions of brand equity on them and in which degrees. The various opinions will be examined and grouped according to the differentiations of the education level and age group. Last of all, some key finding that figured out via this research will be used to conclude this chapter.

Demographics

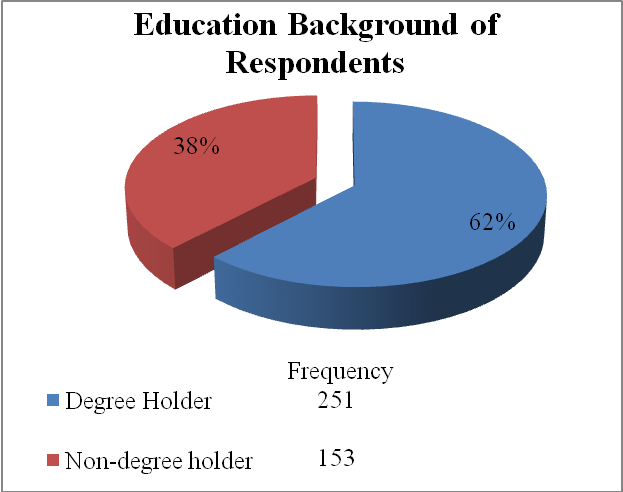

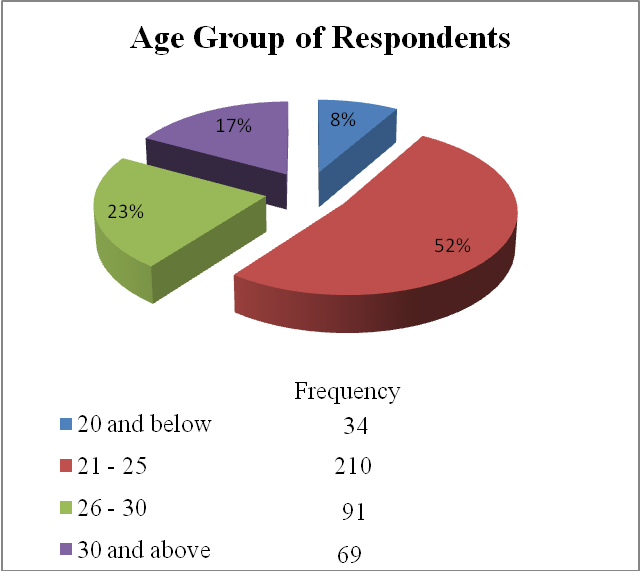

The questionnaires that used for this study were posted on the internet and only target for Chinese at May 17th, 2010 and the author closed the data collection at June 1st, 2010. During that period, 404 people had participated in this online survey. These responses were critically analyzed by the author to fill the gaps that pointed out in the literature review part. The education background of the 404 respondents was displayed in the following Table 4.3.1, that 62% of them are certificated with a degree and the rest 38% are non-degree holders. In addition, the Table 4.3.2 presented the age group of the respondents; the biggest age group is from 21 to 25 years old that 210 respondents are in it and takes 51.98%. Moreover, the second one is from 26 to 30 which including 91 respondents (22.52%) and then 69 respondents (17.08%) were at the age of 30 or above. Lastly, only 34 respondents (8.42%) are 20 years old or below.

Primary Data Analysis

The general impact of hotel brand equity on Chinese

The section 2 (Question 2.1 – 2.6) was designed to investigate the overall impact of brand equity on Chinese customers.As listed in the Appendix II, among the 404 respondents, 81% (327) of them had stayed in branded hotel before. Moreover, 64% of respondents said they are willing to pay more for international brand hotel in China comparing with local one. According to that, the author found that the international brand hotel is considered to provide higher value of the money on Chinese customers’ perception.

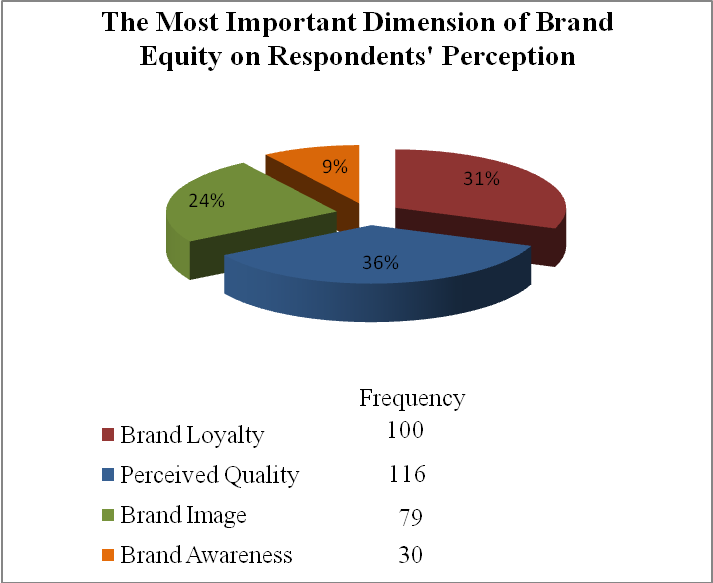

Perceived quality was found to the greatest influencer of the choice of a hotel among Chinese. Additionally, 80 % (325) of respondents said they think the brand equity is important and they will take it into consideration when they select hotels in China. It shows brand equity is essential to Chinese customers and becomes a dominated factor on their hotel selection. As showed in the following Table 4.4.1, among the 325 respondents who thought the brand equity is important, most of them (36%) considered the perceived quality as the most important dimension of brand equity to them. In addition, 31% of respondents selected brand loyalty while 24% selected Brand image. But only 30 respondents (9%) thought brand awareness is the most important. Besides, the brand equity also has a significant impact on Chinese customers’ decision of revisiting certain hotel, due to 327 respondents (81%) stated that they prefer to choice their familiar hotel brand even when other hotels have some features as it. Based on the above information, it is clear for the author that the brand equity is an important reference for Chinese customers’ hotel selection and so have a strong impact on it.

This research reveals that quality is vital in any form of business. In this regard, perceived quality in hotel industry therefore becomes the main element of all the loyalty and equity components. Quality is however not as most people would look at it, like in one-dimensional construct. The main areas that quality usually forces on are important for the Chinese hotels for their competence. This can enable them to find out what makes clients consider certain hotels as service quality and from these they will know the type of adjustments to make and enhance their brand loyalty.

Overall, things like noise level from cooling fun, computer, traffic, power and other machinery around can amount to discomfort at some point.

Chinese perception of the four dimensions of brand equity

Section 3 (Question 3.1-3.4) of the questionnaire are divided into four part by the author for the purpose of evaluating the four dimensions of the brand equity, brand loyalty (Question 3.1a – 3.1d), perceived quality (Question 3.2a – 3.2f), brand image (Question 3.3a – 3.3f), and brand awareness (Question 3.4a – 3.4 c).

Key Findings and Conclusions

The study revealed that brand loyalty, brand awareness, the perception of the clients regarding the quality of the hotel and the impression of image in the same context greatly influenced the choice of these hotels. Brand loyalty and awareness were the greatest forces according to these results.

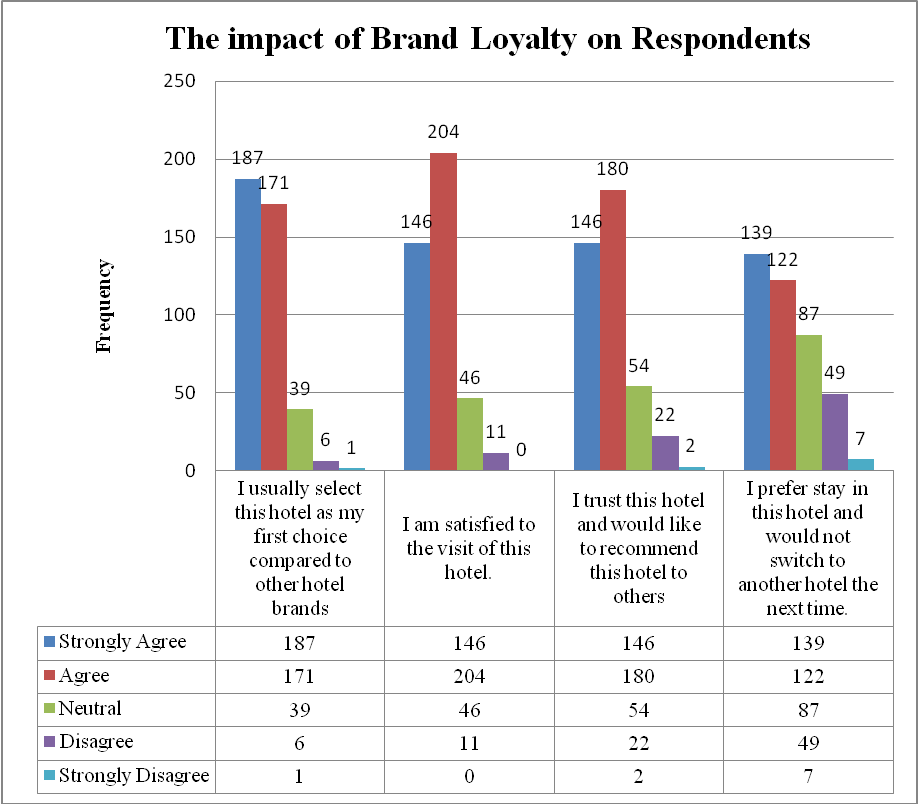

As listed the above Table 4.5.1, 187 (46.3%) respondents strongly agreed and 171 (42.3%) respondents agreed on the first statement that they choice the hotel since they used to consider it as the first choice while only 7 (1.7%) respondents hold the opposite opinion. And 350 (86.6%) respondents said they choice the hotel because they were satisfied with visiting this hotel and no one strongly disagreed on this point. Moreover, around 326 (80.7%) respondent select hotels in China based on their personal trust of certain hotel and they even want to recommend it to others. However, 261 (64.6%) respondents stated they choice the hotel since they prefer it and would not consider switching to other hotels.

It shows brand loyalty in the Chinese hotels is instigated by the presence of familiar brands some which are all over the country and even abroad. People hence tend to stick to the hotel they like most and tend to think that it could be risky to visit the hotel brands that are not familiar. Therefore mean that people reaction to what is being offered on the market as brands is usually very personal. This is why many Hotels are now adopting the personalized branding to meet customer needs.

The changes have included construction and renovation of presidential suites like the famous Hilton Shanghai has done. The decision of the customers are based on what they feel is good for them on long term basis. This then builds up the loyalty. This is where individuals make very critical personal economic sacrifices just to end up in the specific hotel based on their previous encounters. They also fear risking to go to other new hotels because they comfortable with what they have and going to a new one rather a change could amount to a risk that bears personal consequences as such, they tend to avoid the social risk and stick to the brands that they are familiar with.

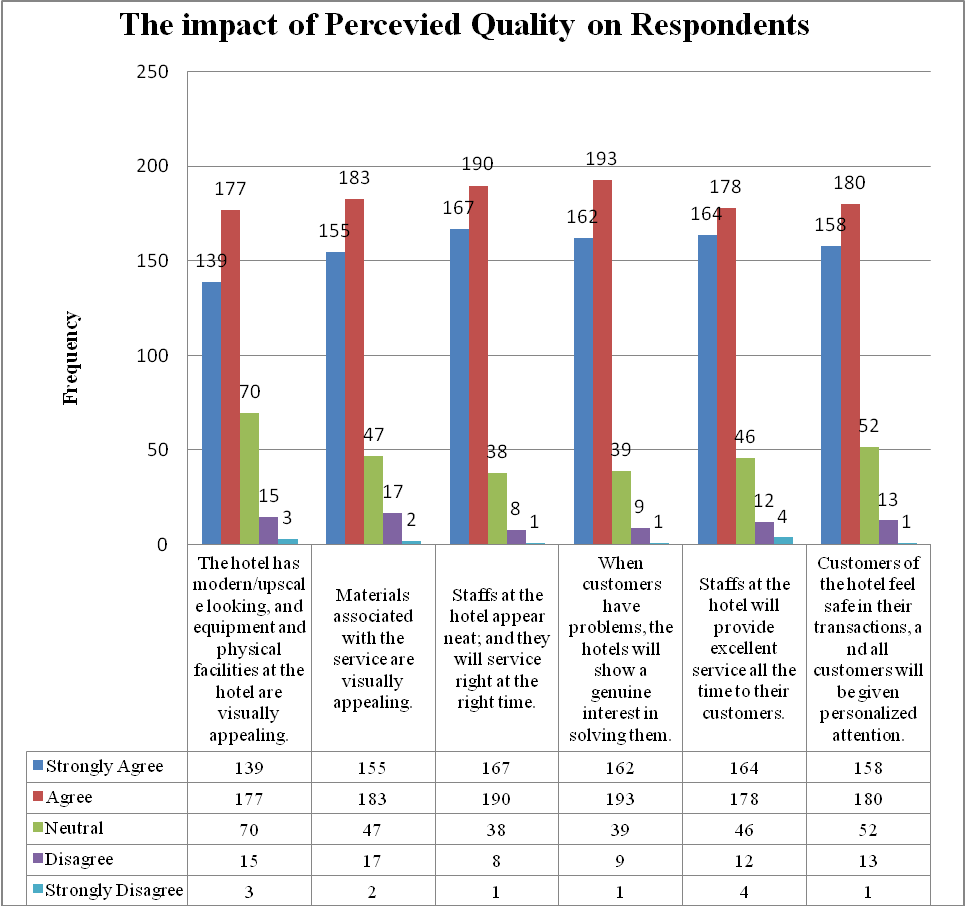

Perceived brand quality was the most significant element that determined the choice of a particular hotel among the Chinese population. Perceived quality as a factor in marketing and branding is very important in hotel management. Customers usually tend to like products that are of superior quality or superior services in accordance to the use and also the available alternatives.This is why the question sought to find out thing things that attracted or influence the choice of clients among them including modern facilities. The response for modern facility was overwhelmingly higher in agreement as 177 (43.8%) agreed while 139 (34.4%) strongly agreed as opposed to only 15 (3.7%) people who disagreed. Quality also became evident as a large number of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that they prefer to visit a hotel if it had excellent services, neat attendants and the services is timely (see Table 4.5.2).

The notion of perceived quality is indescribable overall impression of a brand. This is based on the underlying characteristic that the brand has to ensure that it is reliable and efficient in performance. To emphasize on this presumption, the outcomes of the research indicates that most of the participants as indicated in the above Table 4.5.2, factors that influenced their choice were, excellent service, factor attendance and problem solving, a feeling of security and overall personalized service. The perceived quality also signifies the strength of a brand and this is what drive the increase in market share and translates to lower unit cost via scale economies.

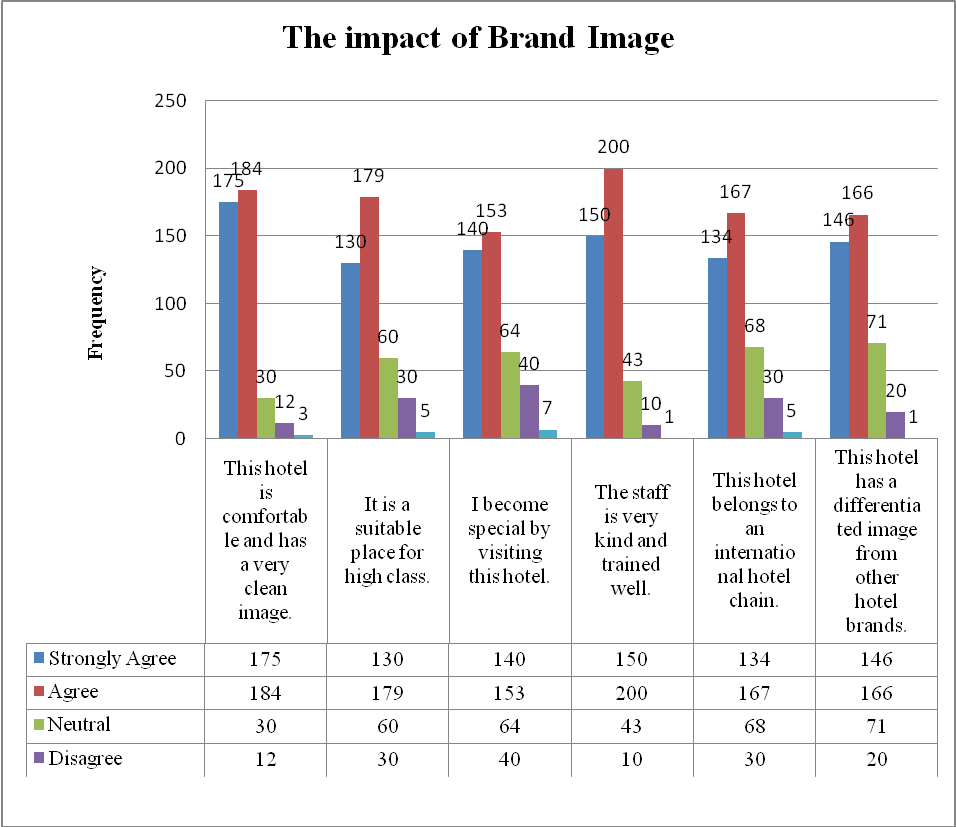

Brand image is critical in determining the consumer preference since it plays on the self-expression and the symbolic worth of the product to the consumer. In this regard, the consumer’s level of self-monitoring is greatly influential on the brand preferences shown by the users. This is what creates the intention of acquiring the product in the consumers and results in actual buying. Positive Brand image perceptions and beliefs translate to more purchase of the product. This is evident from the table above in that the participant would purchase services of a hotel that is of international standards, provides better comfort, where they will be appreciated and will feel special and generally in hotels that are perceived to be of high-class people.

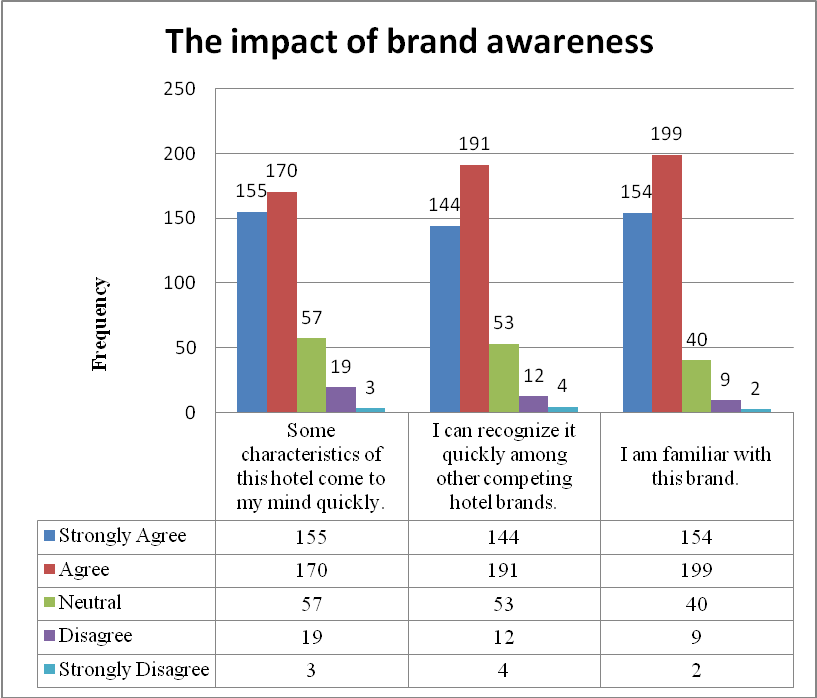

Brand awareness contributes to clients’ decision making even more than image or association. When individuals are aware of a certain hotel because of its reputation, they are likely to use its services because of the familiarity rather than seek a new hotel whose services are not clear. For this reason, most responds agreed that they chose a hotel to stay because they were familiar with it (see Table 4.5.4). The respondents again agreed that they chose a hotel they clearly understood their characteristics.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Introduction

Brand equity is a unique strategy used in marketing and this usually comes with a promise of gaining consumer loyalty. This strategy designs a brand that has specific attributes and qualities exclusively designed – in most cases they are customized (consumer – based) for attracting customers. When brand equity is gained, the brand is able to gain a sustainable competitive capacity. Therefore proper managing of these brand equity is paramount for attaining success of the brand. Here are summaries of concepts to enhance brand equity.

Conclusion

Brand loyalty can be used to enhance relationships involving firm’s most precious consumers in competitive industry of hotel and hospitality. Many hotels run a number of brands under very big umbrella so as to ensure their survival by benefiting from the brand loyalty. The clients can actually respond that the brand is trustworthy and that they always live up to their promises. Furthermore being treated nicely and deals with the problem when they arise. Loyal customers, would state that they are proud to be customers to that hotel since the customers are treated with respects.

Perceived quality is basically the reason that customers make purchases and in this sense, it also forms the end result measure of the brand identity. Interestingly though, the supposed worth reflects integrity that is indicated by all aspects of the brand like quietness, entertainment, time efficiency, neatness and timeliness. Functional benefits in most cases define brand identity and this is what described quality since the life of the customer is improved. Attempts of establishing quality are usually very hard to achieve unless that claim is substantial. Perceived quality differs greatly from the real quality in a number or reasons. Basically consumers could be excessively pressured by previous image of lesser quality. This way, they may not believe the claim. A firm on the other hand can be seen to be achieving better quality on a dimension that clients do not actually regard as significant.

The image that surrounds the firm’s brand is the basic principle basis of the aggressive advantage and consequently a valuable strategic asset. Sadly, many firms and not proficient at disseminating a strong, clearly message that not only distinguish the brand from competition, but also distinguish it in unforgettable and optimistic manner. Chinese hotels should view the brand that is and not just a product or service, but generally a brand image that indicates philosophies of the firm.

Recommendations

Brand loyalty can be result is long-term sustainability of a brand therefore the management should always ensure that the specific quality that make the brand stand out from the rest are never compromised. This therefore means that a culture of quality management should be established. Business Brands should be able to establish the capacity to connect clients of various properties with a common loyalty program- this is the one that rewards regency.

Regarding quality perceived, it is very important for hotel managers to work across brands. A hotel brand is usually very different from what is called luxury brand and not similar with family brand. Building brand loyalty based on the needs and requirements of customers, rather than on the services or products. Clients are the ones who determine value. When they see an opportunity to save some money or get to some information buying the product, they will ensure that they actually purchase this product so that they get double benefit. Brand loyalty can be achieved effectively across the world by ensuring that clients are able to access common services in hotels as well as other related products even when their needs are different. When company is big, it can benefit from the scale economies, this is why it is important to seek expansion when trying to work brand equity.

Managers should bear in mind that Brand loyalty plays a big role when the decision of clients are an indication of personal image and that they could have long-term outcomes. Clients usually understand that by making a decision, and then they are making major sacrifices either personally of socially. A wrong decision on the other hand implies that the consumer will have to suffer the risk that is portended. Managers should be aware that the success of a brand can be achieved when a hotel in this context engages in a program to build loyalty. This is the effort of the company to build identity with a certain brand based on the clients feeling of pride, trust, self-image and quality. When loyalty is tracked, the worthiness of the product is assessed. The workers should be encouraged to be dedicated towards offering excellent service.

General information to consider includes how much clients are satisfied, their likelihood to purchase services and product of that hotel and the likelihood that they could recommend that hotel to another person. In order to improve on brand loyalty and ensure that the brand is consider the first choice for them; Loyalty programs are so far very efficient in making that hotel a brand selection and this way it can secure repeat purchases. To assist in securing a business future via a hard economic environment, business management should consider the behavior of best customers and try to understand the way the can attain the repeat purchase culture from this concern.

The Chinese hotels should be able to achieve Total Quality Management so that the outcome is positive. Perceived quality is in most cases the major item that assists to position dimension corporate brands and other brands that cover other products.

In addressing the perceived quality, the hotels in China have to understand that quality is a strategy thrust. The way clients perceive quality in different ways and it’s the main strategy used in business. Perceived quality in real sense measures the goodness of a brand. The main influence to perceived quality is to comprehend and manage these cues correctly. Hence, it is vital to understand the modest things that clients utilize as the grounds for making a judgment.

Brand loyalty with regards to client’s conscious or insensible choice, expressed via intent or character, and to repurchase a brand persistently. Client’s characteristic is habitual as they could be safe and familiar. In order to enhance brand loyalty with regards to image and choice, advertisers have to break consumer habits and enhance these behaviors by reminding them the worth of their product and support them to continually purchase these products even in future.

From the way a new brand is designed by a hotel, to the final presentation of a product that is mature, efficient marketing tactics relying on serious understanding of what motivation is. The marketing strategy includes management, segmentation, launching new services and items, managing the brand, and consequently that matter of brand loyalty is to be assessed greatly for success. Branding is definitely the main factor that influences the success of a business especially hotel management. With the turbulent economic times being experienced al over the world, Hotel industry in China will have to be typified by even more branding and development of better products and services as the marketing expenses go up and also observed increase in international competition. Whereas successful leveraging of strong brand equities seem to guarantee cheaper introduction of new products, the overall success will rely greatly on basic brand awareness and image among the clients. When designing their marketing mixes, Hotels will have to concentrate on constructing and safeguarding their brand equity. For instance when a certain brand is a premium item, then its quality should be superior (excellent) and consistent in meeting eh expectation s of the consumers. The low sales prices should not be a competing strategy here and the advertisement process should be consistent with premium product standards. Brand extension can be efficient in marketing, however possible dilutive extensions ones that compromising the perception of the clients should not be entertained. When the core brand is not strong in the market, brand extension may not be successful hence need to be avoided as well.

References

Aaker, D. A., & Biel, A. L. (1993). Brand equity & advertising : advertising’s role in building strong brands. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing Brand Equity: capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc.

Aaker, D.A. (1996), “Measuring brand equity across products and markets”, California Management Review, Vol. 38 No.3, pp.102-20.

Aaker, D. A. (2002).Building Strong Brands. New York, The Free Press.

Anselmsson, J., Johansson U. &Persson, N. (2007), Understanding price premium for grocery product: a conceptual model of customer-based brand equity.Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol: 16 (6), pp. 401-414.

Arasli, H. &Kayaman, R. (2007), Customer based brand equity: evidence from the hotel industry, Managing Service Quality, Vol. 17 (1), pp. 92-109.

Ataman B. &Ulengin, B. (2003).A note on the effect of brand image on sales, Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 12 (4), pp. 237-250.

Biel, A. (1992), “How brand image drives brand equity”, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 6 No. November/December.

Chan, A. &Xu, J. B. (2010). A Conceptual framework of hotel experience and customer-based brand equity: some research question and implications. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 22 (2), pp. 174-193

Clark M., Riley M., Wilkie, E. & Wood R. (1998).Researching and Writing Dissertation in Hospitality and Tourism. The Alden Press. Oxford.

Cobb-Walgren, C. J., Ruble, C. A., & Donthu, N. (1995). Brand Equity, Brand Preference, and Purchase Intent. Journal of Advertising, 24(3), 25-40.

Gunter B., Nicholas D., Huntington P. & Williams P., (2002). Online versus offline research: implications for evaluating digital media. Aslib Proceedings, Vol. 54(4), pp. 229-239.

Ha, H.-Y., Janda, S., & Park, S.-K. (2009). Role of satisfaction in an integrative model of brand loyalty: Evidence from China and South Korea. Internatianl Marketing Review , pp. 198-220.

Hospitality Industry Boasts Record Growth in China. (2008). China International Exhibition Ltd. Web.

Lohmann, M. & Schmucker J. D. (2009).Internet Research differs from research on internet users: some methodological insight into online travel research. Tourism Review, Vol. 64(1), pp. 32-47.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity.Journal of Marketing. Vol. 57 (1), pp. 1-22.

Keller, K. L. (1998), Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Keller, K. L. (2000), The brand report card, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 1, pp. 147-57, January-February.

Keller, K. L. (2003), Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring and Managing Brand Equity, 2nd ed., Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2003). How Do Brands Create Value? MARKETING MANAGEMENT, 12(3), 26-31.

Kim, H.-B., Kim, W. G., & An, J. A. (2003). The Effect of Consumer-Based Brand Equity on Firms’ Financial Performance.Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(4), 335-351.

Kong H. & Cheung C. (2009). RESEARCH IN BRIEF Hotel development in China: a review of the English language literature.International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality.Vol. 22 (3), pp. 341-355.

Koubaa, Y. (2006), “COO: who uses it, when and how it is used”, Taiwan, paper presented at the 9th Conference on Global Business and Technologies Association.

Koubaa Y. (2008), Country of origin, brand image perception, and brand image structure, Asia Pacific of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 20 (2), pp.139-155.

Kim, H. and Kim, W.G. (2005), The relationship between brand equity and firms’ performance in luxury hotels and restaurants, Tourism Management, Vol. 26, pp. 549-60.

Laverie, D. A., Wilcox J. B., Kolyesnikova, N., Duhan, D. F. & Dodd T. H. (2008), Facts of brand equity and brand survival: a longitudinal examination,International Journal of Wine Business Research, Vol. 22 (3), pp. 202-214.

Lockshin, L. & Spawton, A.L. (2001),Using involvement and brand equity to develop a wine tourism strategy,International Journal of Wine Marketing, Vol. 13 (1), pp.72-81.

Lohmann M. &Schmucker J. D. (2009).Internet Research differs from research on internet users: some methodological insight into online travel research. Tourism Review. Vol. 64(1), pp. 32-47

Ogba, I.-E., & Tan, Z. (2009). Exploring the impact of brand image on customer loyalty and commitment in China. Journal of Technology Management in China , Vol. 14(2), pp. 132-144.

PROGRESS AND PRIORITIES 2005/06, (2005).World Travel & Tourism Council. Web.

Pine, R., & Qi, P. (2004). Barriers to hotel chain development in China. International Journal of Contempopary Hospitality Management , Vol. 16(1), pp. 37-44.

Pine, R., Zhang, H. Q., & Qi, P. (2000). The challenges and opportunities of franchising in China’s hotel industry. International Journal of Contempopary Hospitality , Vol. 12(5) pp. 300-307.

Ross, S. (2006), A conceptual framework for understanding spectator-based brand equity, Journal of Sport Management, Vol. 20(1), pp. 22-38.

Saunders, M., Philip, L., & Thornhill, A. (2007).Research methods for business student (4th Ed.).Essex, England: Person Education Limited.

Saunders, M., Philip, L., &Thornhill, A. (2009).Research methods for business student (5th Ed.).Essex, England: Person Education Limited.

So, K. K.F. & K, C. (2010), “When Experience Matters” Building and Measuring Hotel Brand Equity – The Customer’ Perspective.International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. Vol. 22 (5), pp

TANG, L. (2007). Chinese Culture and Chinese Consumer Behaviour. In C. Ammi (Ed.), Global consumer behaviour.UK: Wiley-ISTE.

Tait (2010).Chinese Internet Usage Report – Jan 2010 – Summary and Insights. East – West – Connect. Web.

Tolba, H. A. & Hassan, S. S. (2009).Linking customer-based brand equity with brand market performance: a managerial approach.Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 18 (5), pp. 36-366.

TRAVEL & TOURISM ECONOMIC IMPACT – CHINA 2010. (2010). World Travel & Tourism Council. Web.

Wang Y., Vela M. R. & Tyler K. (2008). Cultural perspectives: Chinese perceptions of UK hotel service quality. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, Vol. 2 (2), pp. 312-329.

Wang, H., Wei, Y. &Yu, C. (2008). Global brand equity model: combining customer-based with product-market outcome approaches.Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 17 (5), pp. 305-316.

Yoo, B., &Donthu, N. (2001). An Examination of Selected Marketing Mix Elements and Brand Equity.Journal of Business Research, 52, 1-14.

Yoo, B., Donthu, N., & Lee, S. (2000). An Examination of Selected Marketing Mix Elements and Brand Equity.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(2), 195-211.

Appendix I

Dear Participants,

I am Kasen Xia and a current student of Bachelor Degree in International Hotel and Tourism Management in University centre César Ritz in Switzerland. In order to complete my final module in the school, I have chosen the topic of my industry research project on the impact of Brand Equity on Selecting Hotel in China. This project has already been approval and is in the research process.

To aid my collection of data, I would kindly request you to spare 5 -10 minutes and complete this questionnaire. All the data collected will only be used for academic purposes and kept confidential.

I am looking forward to your valuable opinions and your participation strengthens the creditability of this research.

Thank you for your valuable time and participation!

Yours sincerely,

Kasen Xia

University Center <<César Ritz>>

Englisch-Gruss-Strasse 43

3900 Brig, Switzerland

亲爱的参与者,

本人夏晨,是瑞士凯撒丽斯酒店管理大学,攻读于国际酒店暨旅游业管理系学士学位课程的中国留学生。我的毕业论文的题目是《品牌资产对于在中国选择酒店的影响》。校方已批准了论文的开题报告并正式进入研究阶段。

为了完成今次研究,本人需要搜集相关的数据,现诚希阁下在2010年5月20日之前,能花5 – 10 分钟的时间完成这份问卷。问卷所有资料将会保密,只作为这次学术研究用途。

我期待着您的宝贵意见,您的参与必将令本次研究更有价值。

夏晨敬上

2010 年 5月 16日于瑞士

Section 1: General Information

第一部分:基本信息:

Section 2: The impact of Brand equity:

第二部分:品牌资产的影响力:

Section 3: The four dimensions of brand equity

第三部分:品牌资产的四个方面

The following questions please tick option (1-5) that best corresponds to your most agreement level of each statement.

下面的问题,请您在下面问题中勾出最满意的选项(1 – 5)

I choice this hotel since:

Please list some hotel brands that you frequently visited in China.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Thank you for your valuable time and participation!

感谢你的宝贵时间与参与!

Appendix II

Appendix III

1-5 scale: 1 “Strongly Agree”, 2 “Agree”, 3 “Neutral”, 4 “Disagree”, 5 “Strongly Disagree”