Abstract

Innovation is a critical factor that defines the ability of an organization to manage various internal and external challenges and realize its goals within a given duration. It is important for an organization to foster an innovation culture among its employees to ensure that they can come up with creative ways of addressing various challenges that they face in their workplace environment. Such a culture must be cultivated through various strategies, such as training, employee engagement, and employee empowerment. Regular training of employees empowers them because it offers new skills and strategies that can be used to undertake various tasks in a new approach. The training fosters a learning culture where employees feel committed to embracing creative ways of handling tasks assigned to them. It is important to understand drivers that support training and constraints that limit it in the context of state-owned organizations. Increased budgetary allocations, the presence of experts who can help in the training process, a close relationship between top leaders and junior employees, and improved technology. Poor communication between management and employees, limited resources, and increased reliance on expatriates are some of the major constraints. In this research, the researcher seeks to explore factors affecting learning culture and fostering innovation in the state-owned organization in UAE.

Research Agenda

Problem Statement

In the rapidly developing modern business environment, the organizational sustainability of companies is constantly challenged by both internal and external factors. They had to face competitive pressures, which necessitate innovation in order to stay afloat. Innovation may cover a wide range of business issues, including technologies, management, products, services, procedures, etc. (Drucker 2014). Although leaders realize that innovation is essential for the survival of the company and its potential growth, there is no universal model that would suit all firms. Business researchers agree that a truly innovative organization must have a strong organizational culture fostering advancements; however, they disagree upon the set of factors that shape this culture (Sheehan, Garavan & Carbery 2014).

Learning and Innovation

There is an increasing interest in the relationship between learning and innovation capacity, suggesting that one is impossible without the other. While a lot of attention is given to knowledge needed to be obtained to foster innovation, there is a considerable lack of investigation of values and attitudes that are no less significant (Chiva, Ghauri & Alegre, 2014). Although the concept has often been addressed in the literature, which mainly highlighted its positive effects, there is still no holistic study that would identify which practices lead to the formation of a learning culture (Tseng & McLean 2008).

Organizational learning goes far beyond training. This complex process is aimed to create behaviors and attitudes that would potentially lead to change and development. Information received by employees in the course of training does not equal learning. It must be interpreted and fully understood before being transformed into knowledge (Drucker 2014). Currently, the majority of organizations fail to realize that knowledge cannot lead to successful innovation unless it is coupled with corresponding cognitive and behavioral changes of employees (Senge 2014). Thus, the concept of organizational learning is elusive and is typically viewed from one perspective. This is the major problem that necessitates research that would identify factors determining a learning culture and link them with the capacity for innovation.

Learning Culture and Innovation Among State-Owned Enterprises

It is noteworthy that some state-owned organizations in the UAE pay little attention to human resources training and development. The learning culture in such entities is underdeveloped (Harry 2016). The Emirati business environment is still characterized by the focus on on-job training that implies the transfer of knowledge and skills from employees who work for a while to newcomers or attending training sessions. This approach has proved to be ineffective, which made many private-owned companies focus on learning culture development and innovation. It has been acknowledged that state-owned organizations tend to be less flexible as compared to private ones. However, the effectiveness of state-owned companies and governmental agencies can ensure the success of the entire nation. Emirati people should start seeing state-owned enterprises as the major facilitator of changes, innovation, and progress of the UAE. Hence, the target organization of this study is an Emirati state-owned company.

The shift in the area is already apparent. For instance, Sarker and Al Athmay (2017) state that the modern Emirati business environment is undergoing significant changes that can shape the ways human resources are managed. The government launches various incentives that encourage companies to concentrate on innovation (Harry 2016). This approach is regarded as the major option to enable the country to become one of the leading nations in the region. Some state-owned Middle Eastern organizations have already become innovation-oriented, which has resulted in their success (Tajeddini 2016). These organizations have focused on the development of the learning culture and empowerment of the staff. The experience of these companies can be reviewed, but it is clear that the Emirati context is characterized by certain peculiarities that can affect the implementation of the change.

Therefore, it is pivotal to carry out detailed research to make sure that the changes will be implemented successfully. In order to address the goals of this study, the employees of a state-owned company will participate in the research. It is also noteworthy that many scholars and practitioners focus on management’s views while paying little attention to employees’ attitudes. This study will address this gap as well and will analyze the perspectives of stakeholders at different organizational levels. The analysis of the viewpoints of different employees will provide insight into many possible barriers as well as opportunities for the implementation of change. This study aims at identifying the underlying factors affecting the development of the learning culture in state-owned companies as well as its influence on innovation. A framework for the transfer to the innovative learning culture in a state-owned organization will also be provided.

Conceptual Model

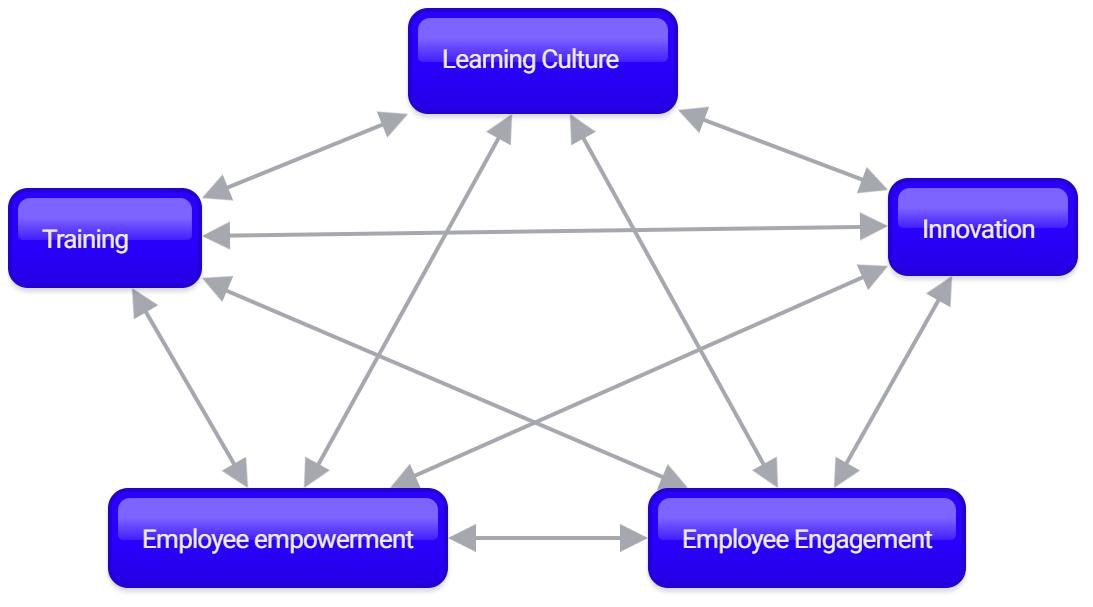

Regarding the issue under analysis as well as the set objectives, the following section suggests and discusses a conceptual model provided above (see fig. 1). The existing literature sheds light on the value of such elements as employee engagement and empowerment that contribute to the development and adoption of the learning and innovation culture. These model components are to be reviewed.

The Analysis of Major Concepts

Prior to considering the major concepts central to this research, it is important to identify the value of the conceptual framework. When implementing a qualitative study, researchers often have to handle multiple ideas and concepts, which makes it rather difficult to maintain conceptual congruence. The development of a conceptual framework can help in maintaining the focus of the research. This paradigm helps researchers capture the most relevant meanings in the ideas and concepts employed during the study (Merriam & Tisdell 2015). Such models also reveal the links and various relationships among the concepts. The conceptual framework guides the research and is instrumental in the implementation of the in-depth analysis. Further in this section, the primary concepts, as well as the ways they correlate with each other, will be discussed.

One of the primary concepts employed during this study is staff training that can be defined as a set of discussions, programs, and interventions aimed at knowledge and skills formation and staff development in particular areas. Baycan (2016) stresses that on-job training tends to be organization-specific. In simple terms, companies try to help their employees develop knowledge and skills that will ensure reaching the existing organizational goals. Baycan (2016) adds that technology-based training programs are now common as top managers try to ensure the use of the most recent technological advances that appear each year or even month. Eidizadeh, Salehzadeh, and Esfahani (2017) emphasize that technology is one of the primary drivers that facilitate the training process. New technologies that are introduced into the business world make top managers pay more attention to training and staff development. Clearly, formal education can hardly equip people with the necessary skills and knowledge as this area is evolving at a considerable pace.

It has been found that training can be facilitated under certain circumstances, and employee empowerment and engagement are crucial to creating the most favorable atmosphere for the learning process. Employee empowerment can be referred to as a set of practices aimed at encouraging the staff to make decisions independently and address problems developing various solutions (Hanaysha 2016). In simple words, employees receive more freedom and power to accomplish tasks and achieve organizational goals. Researchers have explored various types of employee empowerment classified according to the focus of the practice. For instance, some managers concentrate on communication while others try to introduce practices aimed at problem-solving (Hanaysha & Tahir 2016). Irrespective of the type of empowerment, it contributes to improved employee performance. Researchers agree that empowerment has a positive impact on employees’ self-esteem and creativity through obtaining more autonomy and training.

The concept of empowerment is closely linked to the one of training as people who feel empowered are more likely to embrace changes and focus on self-development. People who feel confident are more likely to seek training options, and they are willing to take an active part in programs and interventions aimed at the development of various skills. These people self-reflect and try to identify gaps in their knowledge and skills, and they are confident enough to admit having gaps and to initiate the development or implementation of a corresponding training program. Ford (2014) notes that such employees have enhanced self-esteem, which has a positive effect on their creativity, decision-making, and overall performance.

Engagement is another essential concept guiding this study. This element can be referred to as the extent to which employees are committed to performing their tasks well, contributing to achieving organizational goals, and developing the organization (Joshi & Sodhi 2011). This phenomenon has been well-studied and analyzed from different perspectives. For instance, Bhuvanaiah and Raya (2014) identified three types of employees according to the level of their engagement. Other researchers focus on factors affecting employee engagement (Joshi and Sodhi 2011). Engaged employees often share the values existing in their company and are willing to foster the organizational culture. Many factors can have an impact on the level of employee engagement. Employees’ position and job satisfaction within the organization have a significant influence on their engagement as people who perform tasks they are capable of fulfilling and are satisfied with their jobs are more committed to organizational goals and culture. For the purpose of this study, only some of these factors are taken into consideration. The focus is on the link between engagement, training, empowerment, and innovation as well as a learning culture.

Engagement often correlates with the level of empowerment and employees’ training (Joshi & Sodhi 2011). The link between engagement and training is strong as people who are committed to organizational goals are willing to self-develop and gain new knowledge and skills that can help them contribute to the development of their organizations. The concepts of engagement and empowerment are also closely connected (Joshi & Sodhi 2011). People who are engaged tend to feel empowered as they believe that their voices will be heard and their creativity will be beneficial for the organization. It is possible to note that these concepts affect each other as engaged people feel empowered while people whose self-esteem is high are more willing and able to contribute to the development of their organizations.

Innovation is another concept utilized for the purpose of this study. Innovation can be defined as a multidimensional ability of companies to develop and implement creative solutions when addressing new trends and phenomena existing in their business environment within the scope of the available resources (Gaul 2016). McGuirk, Lenihan, and Hart (2015) emphasize that innovation is created at two levels: organizational and individual. Innovative processes imply the balance between the organizational culture fostering innovation and each employee’s input. Innovation is associated with the focus on new approaches and methods as well as the use of the most advanced technologies. Researchers agree that human capital is the major driving force for the development of learning culture (Olsen 2017; Van Uden, Knoben & Vermeulen 2017). Innovation is also associated with change and the degree of employees’ readiness to embrace it.

These features make this concept linked to the one of training. Technology is evolving at a significant pace and employees should have the up-to-date knowledge to use the most recent technological advances. Raising employees’ awareness of novel strategies and methods to address certain issues will also foster creativity and innovation (Dawson & Andriopoulos 2014). Additionally, training implies more effective communication and collaboration that are pivotal for innovation (Linke & Zerfass 2011). At the same time, innovation also has an impact on training that is becoming more effective while making employees more empowered. For example, innovative technology is one of the platforms for the development of new effective training programs. Employees’ innovative ideas can be regarded as stimuli and building blocks of training interventions aimed at making a novel approach common within the organization.

In this way, the concept of innovation is associated with employee empowerment. Innovation facilitates knowledge sharing and results in the development of the organizational culture where employees are encouraged to exchange ideas and contribute to the development of new ways to achieve organizational goals (Dawson & Andriopoulos 2014). At the individual level, employees feel empowered when they work on innovative projects as they are a part of a meaningful process. They can see their own input, and when this acknowledgment is accompanied by the appreciation of top management, employees’ self-esteem also improves. The relationship between innovation and engagement is also well-pronounced. The work on innovative projects accompanied by training and empowerment motivates employees to be active contributors to the development of the organization (McGuirk, Lenihan & Hart 2015). Engagement also has an influence on innovation as employees committed to working and achieving organizational goals tend to use their creativity and search for innovative strategies and methods to address their tasks or issues.

Finally, learning culture is one of the central concepts employed in this study. Learning culture can be defined as a practice that implies employees’ and organizations’ willingness to increase their knowledge base and competence in order to improve their performance (Omerzel & Jurdana 2016). Researchers have identified various positive effects a learning culture can have on an organization. For instance, learning cultures are regarded as the major facilitators of employees’ job satisfaction and performance (Egan, Yang & Bartlett 2004). Some scholars concentrate on its impact on the overall performance of companies as well as the development of their competitive advantage.

Learning culture is closely related to innovation as people focus on constant learning and change. They try to develop innovative methods to complete their tasks and improve their (as well as the overall organizational) performance. Likewise, innovation has an influence on the learning culture as it provides the necessary tools to gain knowledge and skills. Again, technology is one of the primary components of this process (Yu et al. 2013). It is possible to claim that innovative ideas and methods are elements of the learning culture.

The link between learning culture and engagement is rather strong as well. Employees committed to organizational goals and taking an active part in the development of their companies tend to be willing to self-develop (Joshi & Sodhi 2011). At the same time, the learning culture also has many effects on employee engagement. It is possible to state that the learning culture is the most favorable environment for fostering employees’ commitment. People who seek self-development are motivated to work for companies having learning cultures as they have an opportunity to continue learning and self-developing.

Finally, learning culture and empowerment are closely connected concepts. On the one hand, learning cultures contribute to employee empowerment as people understand that they are valued and will be heard (Westeren & Westeren 2012). People obtain new skills and knowledge, which makes them more confident and more active. They feel that they have the necessary skills, authority, and autonomy to come up with solutions that can be implemented. On the other hand, empowered employees are eager to embrace changes and facilitate the learning process, which is an important impetus for the development of learning cultures. Empowered employees often become agents of change and contribute to the development of a new or improvement of an existing learning culture.

It is clear that the concepts considered above are mutually dependent as they affect each other (see fig. 1). Training, employee engagement and empowerment, innovation, and learning culture are elements of organizational success. This interdependence will be taken into account when collecting data and analyzing the collected information. The major focus is one of the ways learning culture is affected by employee engagement and empowerment, as well as training and innovation. During this study, the participants will articulate their views on the matter and share their experiences. At the same time, the participants will be encouraged to contemplate the relationships between the concepts. Top managers will be asked about the ways they empowered or engaged employees through training or whether they tried to create or sustain a learning culture (or some of its elements) in their organizations.

Propositions

Numerous researchers have studied the effect of organizational structure, strategy, and leadership on its capacity for innovation. Although its positive effect is evident, there was no attempt to find out how this culture is formed, what its nature is, to what degree its constituents may affect innovation (Tseng & McLean 2008). Innovation is more often regarded to be necessitated by numerous external factors such as market competition. Little attention is paid to the inner capacity of the organization to promote innovation.

Thus, the present study will start from the basic research questions, how a learning culture fosters innovation, and how it can be used to promote innovation culture among employees. The propositions are to be developed accordingly. The first set will be related to the components of a learning culture:

- P1: A learning culture of the organization is based not exclusively on training but also on employee empowerment that creates engagement.

- P2: The degree of influence on the formation of a learning culture is equal for knowledge formation (training aimed at the improvement of the quality of the provided services) and encouragement (empowerment), which together foster knowledge interpretation leading to positive cognitive and behavioral changes (engagement).

Another set of propositions will be related to the impact of learning culture on innovation capacity:

- P1: Employees expect the learning culture to have a positive impact on innovation capacity within a state-owned organization.

- P2: It is expected that a learning culture uniting knowledge with behavioral changes of the employees and supported by the leader initiative (related to employee empowerment) creates favorable conditions for fostering innovation.

The conceptual model provided above (see fig. 1) represents the concept of a learning culture as a combination of training, employee engagement, and employee empowerment. The model reflects a three-fold nature of the organizational learning process: training (which stands for information acquisition by employees), cognitive and behavioral changes (employee engagement in the work process), and encouragement provided by leaders (employee empowerment). In order to contribute to a learning culture, information obtained in the course of training must be understood, interpreted, and transformed into meaning. This newly obtained knowledge creates value that leads to changes in the employee’s perception of his/her role in the organization (Ford 2014). In the event of positive alterations, engagement is created, which inspires employees to translate their knowledge into practice.

However, training is insufficient to achieve involvement, which cannot appear without empowerment on behalf of the leader. Recognizing and rewarding contributions made by employees into the achievement of the common organizational goal is one of the essential factors determining the formation and quality of a learning culture (Olubusayo, Stephen & Maxwell 2014). Even though employees are provided with development opportunities (training), they still need to know that their efforts in self-improvement are appreciated, and their loyalty to the organization is highly valued. It allows not only to increase their self-confidence but also to improve their attitude to work, which has a direct impact on productivity and organizational performance as it encourages workers to aim for quality and new achievements (Hanaysha 2016). Thus, coupled with training, employee empowerment creates engagement, which is an integral component of a learning culture.

Changing cognitive maps of employees leads to their increased understanding of the importance of innovation (Chang et al. 2015). This implies that a strong, high-quality learning culture promotes values, typically attributed to the innovative culture, making the transition smooth and natural both for employees and for company leaders. On the contrary, if innovation becomes a forced process, it is likely to face resistance. This problem necessitates the second research question of the study: How can a learning culture be used to promote innovation among employees?

Research Aim and Objectives

- According to Ali and Park (2016), when conducting research, it is important to define the aim and objectives in very clear terms. They help in determining the path that should be taken in collecting, analyzing, and presenting data. It makes it possible for one to determine if a research project was able to achieve its goals (Spanos 2009). The primary aim of this research project is to explore factors affecting learning culture to foster innovation. The context of the state-owned companies makes it important to take into account the peculiarities of state-owned organizations. These characteristic features are the lack of flexibility and a focus on innovation, reluctance to embrace change, insufficient level of motivation, and commitment to organizational goals (Sarker & Al Athmay 2017). The characteristics mentioned above suggest that it can be ineffective to take into account other companies’ experiences or focus on management perspectives only. It is crucial to examine the views and attitudes of employees at different organizational levels as this will help enhance the motivation and commitment necessary to develop the true learning culture. The specific objectives include the following:

- To identify factors that have an impact on the development of the organizational learning culture in a state-owned company as seen by employees at different organizational levels.

- To explore the ways the learning culture can affect innovation in a state-owned organization as expected by employees at different organizational levels.

- To recommend a framework to help the management insure fostering innovation through organizational learning factor.

Research Questions

The questions defined the nature of data that was collected from both primary and secondary sources. According to Pruzan (2016), if the research questions are not set appropriately, it is possible to have a situation where irrelevant data is collected from various sources. That is why the researcher based the questions on the above objectives. The following are the research questions that guided this project:

- What major factors affect the development of the learning culture in a state-owned company as seen by employees at different levels?

- What major barriers and challenges can arise as seen by the employees of a state-owned enterprise?

- How can the management use learning culture to promote innovation culture among employees?

Research Novelty and Contribution

The major novelty of the research at hand is the approach chosen to address the issue. While the majority of researchers focus on the direct effect of the organizational strategy and HR policies on innovation, this study will address the whole process of creating the capacity for innovation (both direct and indirect agents). Namely, it will first investigate how the learning culture is formed on the basis of employee engagement, which, in its turn, appears as a result of training combined with employee empowerment. The research will dwell upon the nature of each of the enumerated constituents of a learning culture and assess the degree of their influence. It will also investigate how a learning culture can foster innovation as seen by the stakeholders. Thus, the key novelties can be summed up as follows:

- viewing a learning culture as an environment that is based not exclusively on training but also on particular cognitive and behavioral models;

- acknowledging that the influence of different factors on the formation of a learning culture is unequal and estimating its degree in each case;

- addressing the capacity for innovation as a phenomenon that is influenced by employee engagement, empowerment, and training indirectly via the formation of a learning culture.

As for the contribution, the research will make it clear how to develop a learning culture and use it to introduce innovative practices. In particular, the study will:

- contribute to the bulk of knowledge on management commitment and initiative (since a learning culture can be created only with a due level of empowerment);

- give recommendations on how to align a learning culture with organizational needs so that all employees could realize that learning is relevant in their specific position for obtaining particular results within a determined period, which would allow them to feel that they make a difference;

- elaborate a comprehensive approach to the creation of the right environment for learning (a learner-centered environment) that would be favorable for employees and provide them with necessary tools and resources to improve their knowledge and skills and to become self-learners;

Literature Review

In the current competitive and knowledge-driven business environment, organizations are keen on finding ways to edge out their rivals in the market (Tidd 2017). The sustainability of any organization is currently defined by its ability to be unique in its product offering, understand the changing needs of the target population, and meet those needs in the best way possible (Ren & Zhai 2014). According to Park et al. (2013), in such a highly competitive and constantly changing environment, creativity and innovation are critical ingredients for success. In the past, it was believed that change had to be driven by top leaders who were viewed as the most learned and experienced in their respective fields (Brettel & Cleven 2011). However, successful organizations empower their employees to the extent that they can individually play a role in initiating change in their respective work environments. Junior employees understand challenges that they face in their places of work, and therefore, are in the best position to come up with a possible solution that can address the problems (James 2017). They need to be capable of coming up with creative solutions to manage emerging and existing problems. However, that capability is highly dependent on their levels of training and the culture of innovation within an organization (Linke & Zerfass 2011).

Skerlavaj, Song, and Lee (2010) mentioned that learning culture and innovation among employees are virtues, which must be inculcated within an entity. It must be fostered by the top management through continuous training and development, which is based on the changing environmental forces (Mayer 2012). Organizations must understand that as technology brings about new trends and approaches to doing business their employees need to be empowered through training and development (McNabb 2015). The leaders need to understand the new trends and be capable of working in the increasingly challenging business environment. Organizational culture is a fundamental factor in fostering learning culture and innovation (Shavinina 2013). It can be a driver or a constraint of training within an entity depending on the approach that the top leaders have taken. Song and Chermack (2008) say that leadership is also a major force that defines how innovative an organization can be, especially when faced with changes that must be addressed to protect the survival of the organization. The level of education is another factor that many scholars believe defines the ability of employees to deal with challenges they face at the workplace in a creative manner. The manner in which a high school dropout will approach a problem is relatively different from how a graduate will do in the same environment. Numerous other factors may either promote or hinder learning culture and innovation within an organization. Understanding these drivers and constraints is important, especially for the top leaders who are keen on pushing their organizations to higher levels of success (Murad & Kichan 2016). Leaders need to know how to manage the constraints and take advantage of the drivers to create an environment where change, creativity, and innovation become part of the organization culture.

Training

Traditionally, training was considered the responsibility of colleges and other institutions of learning as they prepared employees to enter the labor market (Pantouvakis & Bouranta 2017). These institutions remain the primary training grounds in modern society as they shape the future generation of workers. However, the changing forces in the workplace environment have made it necessary for employees to get further training even after graduating from college. The emerging technologies are bringing about new ways of undertaking various tasks in the workplace environment. Some employees graduated from college over twenty years ago when some of the current technological practices were not in existence. They have to learn the emerging ways of working as changes emerge (Høyrup 2012). The training that they get at college only offers them a basis upon which they can learn new methods of working. Successful organizations have learned the importance of creating systems and structures that either can facilitate the training of employees in their workstations or organize seminars so that their skills can be aligned with the changing demands of the workplace. Change is inevitable, and employees can only embrace it if they are constantly equipped with the relevant skills (Morpeth & Hongliang 2015).

In many organizations around the world, the ability of an employee to understand and embrace new methods of undertaking their duties, especially those that are technology-based, is highly valued. Leaders and supervisors’ constant praises for such flexible employees make their colleagues develop the urge to learn new skills. They develop a positive attitude towards training as a means of learning the new technology-based strategies (Baycan 2016). To them, training offers the skills that will make them as efficient as their techno-savvy colleagues. It eliminates cases where they lack a sense of belonging because of their inadequacies. Dobni (2008) says that when an employee feels that his or her skills are inadequate, they may develop the inferiority complex problem as a major problem that hinders their ability to work properly within an organization. They will despise themselves and view others as being superior to them even when that is not the case (Pandey & Upadhyay 2016). In such circumstances when their problems become psychological, they are susceptible to committing mistakes that compromise their output within the organization. If such a problem is not arrested in time, the fear that they may lose their jobs may emerge (Della, Scott & Hinton 2012). Such employees may develop strong resentment towards their colleagues and leaders, as they feel marginalized and unappreciated. Many top leaders, out of the desire to eliminate such undesirable eventualities, feel obligated to train their employees to empower them. They believe that in so doing, unity and cohesion will be created, other than the improved performance expected out of the newly gained skills. Many multinational companies such as Mercedes Benz of Germany and Toyota Corporation of Japan have invested heavily into projects meant to empower their employees and create unity and teamwork by aligning their skills with job requirements (Jockenhofer 2013).

It is important to appreciate that a number of constraints exist that may make it difficult to promote training in an organizational setting (Gibson 2015). Organizations can come up with training programs because of the global or natural pressure to improve the skills and competencies of their employees. However, that may not be enough if there is no commitment among the employees who are directly involved in such programs. Wang and Ahmed (2016) say that when the employees do not see the relevance of training, then the investment made by the management may not yield the desired outcome. They may attend the training sessions, but it may not amount to much because of a lack of commitment. Another major social constraint faced by many organizations in training their employees is discrimination and racism. The problem is very common in the United States and parts of Europe. According to Yu et al. (2013), the United States has made impressive steps towards eradicating the problem of racial discrimination and other practices of stereotyping. However, the problem is not far from over. It is common to find cases where people of the same race form teams within organizations because they do not feel they belong to people of the other races. That is a major hindrance, especially when these employees have to work as a unit during training (Neskakis 2012). The mistrust among people on racial lines makes it difficult to make them committed to issues meant for the mutual benefit of all employees such as regular training.

The economic environment may also have a significant impact on the training of employees with the view of fostering a learning culture and innovation among employees. The need to achieve economic success is one of the key drivers of training in the modern business environment (Dawson & Andriopoulos 2014). Companies know that their survival depends on their ability to maintain their market share and attract more customers despite the increasing level of market competition. The need to meet the needs of customers in the best way possible has never been more relevant than it is today (Clark 2013). The emergence of local and international competitors means that organizations must find ways of making their products unique in the market. They must also find ways of improving the quality of their products while at the same time lowering their cost of production through improved efficiency. That can only be achieved if they have a team of the highly skilled and innovative workforce (Høyrup 2012). The employees must be capable of understanding the challenges that their organizations go through and be able to come up with creative solutions. The knowledge gained in the institutions of higher learning is important but not enough in the current highly challenging business environment. More is always demanded of employees every time there is a major change within the industry, and that can only be realized through more training (Jockenhofer 2013). Companies such as Google have come up with very effective training programs for their employees to make them more efficient in their workplaces. The desire to achieve greater economic success is driving these companies to invest more in enhancing the skills of their employees.

In some cases, Training programs are often costly ventures that reduce the profitability of an organization. Some of the emerging changes brought about by new technology often force organizations to invest a lot in employee training (Clark 2013). Sometimes they have to be sent to other countries so that they can learn the new concepts in settings where they have been embraced. Organizations can only afford to invest in such programs if they are enjoyed impressive economic growth. When there is an economic crunch, many organizations often scale down on training costs. According to Dobni (2010), the 2008 global economic recession affected so many companies in Europe and North America. Many of these companies were forced to scale down on their expenses as their revenues continued to shrink. It reached a time when many companies considered the training of the employees as a less demanding need at that time. Although the stakeholders appreciated the need to train regularly the employees to make them more efficient and productive, there were other more pressing economic needs (Baycan 2016). Such economic constraints often emerge, and when they do, organizations often consider reducing their expenses on training. When such reductions are made, the quality and frequency with which such exercises are offered are compromised.

Technology is by far one of the most important drivers of regular employee training in modern society (Baycan 2016). It can be dangerous for an organization to ignore the emerging technological changes in the market. According to Pantouvakis and Bouranta (2017), technology has made training simpler and relatively cheaper than it was in the past. Because of the new inventions in the field of communication, it is easy for employees to learn new skills in their workplace or at home without necessarily visiting other countries or institutions of higher learning. Through technologies such as video-conferencing, it is easy for employees and their trainers to interact irrespective of their geographic locations (Wang & Ahmed 2016). The new technologies have also improved engagement among the employees and between employees and the top leaders. It is now easy to share new knowledge through various internal platforms within companies.

According to Eidizadeh, Salehzadeh, and Esfahani (2017), although technology is one of the leading drivers of training, in some cases it can be a major hindrance that makes it difficult to achieve the set training goals. Social media is one of the biggest success stories of technology in modern society. Many employees tend to waste time on social media (Prescott 2016). From a distance, one may think that they are engaged in constructive work in their workplaces (James 2017). However, a close look may reveal that they are spending most of their time talking to friends about entertaining themselves. This problem is always common during training sessions. Companies are often forced to spend a significant amount of their resources to sponsor training programs (Tidd 2017). However, some employees spend their training time on social media instead of engaging in training-related activities. They end up learning very little despite the time and resources invested in such projects.

Employee Engagement

Employee engagement can be defined as a level of employees’ involvement in organization processes as well as their willingness to share organization values and follow its mission. Engagement presupposes that the employee is not only aware of his/her duties and responsibilities to the company, but also strives to contribute to the achievement of its goals in a joint effort with his/her co-workers. As a result of such engagement, a positive emotional connection between the employee and the workplace is established. Highly engaged workers are willing to achieve excellence that would go beyond their scope of responsibilities and the call of duty. The first attempt to conceptualize the idea of employee engagement was made by Kahn (1990, p. 694), who defined it as “harnessing of organizational members’ selves to their work roles”. He believed that people who are involved in the work process, express their engagement not only emotionally but also cognitively and physically even when they perform routine tasks.

There are plenty of different factors identified by scholars that allow defining whether the employee is engaged. They are mostly based on the employee’s behaviors that are beneficial for the organization. All researchers agree that people are the factor that cannot be duplicated by the market rivals and, therefore, can be considered their most powerful success drivers provided that they feel committed to the organization’s goals and mission. Kahn (1990) also specified that there are three major psychological conditions that are required to make workers involved in the process. They are the meaningfulness of work processes, the safety of operations, and the availability of the necessary resources. Buсkingham and Coffman (2014) believe that engagement results from putting the right people in the right places and exercising due control of their activity. This makes a person intellectually and emotionally committed to the company’s values.

Gorgievski, Bakker, and Schaufeli (2010) believe that behavioral investment of individual intellectual and physical energy should be accompanied by a particular psychological state to call an employee engaged. This implies that a worker can be diligent in performing his/her duties but still fail to be involved and emotionally bound with the company. Employees must have an intrinsic passion for excellence and improvement; without this spiritual element, they cannot be called truly engaged.

There are three commonly identified types of employees: those who are actively involved in the work process, those who are not, and those who are actively disengaged (as compared to the second type). Representatives of the first group are willing to excel in their positions and roles and share organizational values in pursuing the same goals. The second group includes workers who diligently perform their tasks but do not feel any obligation in following the same mission. Thus, they simply do what they are told to do without any further considerations. The third group of employees may undermine the success of the firm since they not only lack motivation (as the second type) but also make efforts to demotivate their co-workers (Bhuvanaiah & Raya 2014).

Joshi and Sodhi (2011) identified six key management functions that determine employee engagement in the work process. They include pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits, work content, work-life balance, the scope of advancement and career-building, relations between the employee and top management, and team orientation. The researchers believe that the lack of even one of the determinants might result in the lack of motivation. Although the terminology may differ across studies, the majority of scholars agree on the content.

The work environment is typically recognized to be one of the most important determinants since managers that create favorable working conditions thereby demonstrate concern for their employees. As a result, the latter are motivated to voice their needs, gain new knowledge, develop their skills, and demonstrate creativity in resolving various work-related problems (Joshi & Sodhi 2011). Some scholars consider that this is the primary factor of employee engagement.

Leadership is the second most popular criterion among researchers since it is believed that employee involvement occurs naturally if leaders manage to inspire and motivate them. However, effective leadership must go beyond exercising control and providing incentives. It also includes many other dimensions such as effective information processing, transparency, self-awareness, high moral standards, etc. It is leaders who are responsible for convincing employees that their role in the organization is significant and directly affects the company’s performance and success (Zhang & Zhou 2014).

Team orientation and relationships with colleagues comprise an interpersonal aspect of the engagement. According to Kahn (1990), teamwork and supportive relationships make workers believe that their organization is a safe and reliable unity. This way, they are encouraged to undertake new ventures without any fear of fail since they know that they will be assisted and supported by the team.

Training and career-building is the dimension that determines employees’ future orientation and plans. Those who undergo training usually intend to further develop their career. Therefore, they show high accuracy of service performance and increased involvement. Furthermore, training and opportunities for growth positively impact employees’ self-esteem and job satisfaction since they can fulfill their potential (Ford 2014).

Compensation, which makes employees concentrate on work and show initiative, covers both financial and non-financial incentives. A perfect compensation that would ensure employee engagement should include timely payments, bonuses, vouchers, extra holidays, free services, rewards, etc. It has been revealed that recognition and non-pecuniary rewards are no less important than monetary bonuses as they make employees feel obliged to respond to such honors with improved performance and an increased level of engagement (Olubusayo, Stephen & Maxwell, 2014).

Organizational policies, structures, and procedures are also directly connected with involvement. If the organization has flexible work-life policies, it attracts applicants and retains those employees who already work for it. Such companies are less likely to face a turnover problem (Drucker 2014).

Finally, workplace well-being refers to the way employees perceive their work. In other words, it reflects the effect the company produces on its employees. It is believed that the leader’s interest in employees’ well-being is a prerequisite for their loyalty and engagement (Kahn 1990).

Employee Empowerment

Employee empowerment can be defined as means of encouraging workers to act independently, make decisions, and solve problems without any interference from top managers. Thus, it implies giving power and freedom to employees to use their creativity to achieve customer satisfaction. Empowerment also includes sharing information necessary for independent operations as well as providing necessary support. Hanaysha (2016) believes that empowerment is fundamental to success in business since empowered employees demonstrate the highest level of involvement.

Employee empowerment is gaining popularity in the business literature due to the fact that increasing global competition and technological advancement urge organizations to transfer to innovative leadership practices that presuppose the adoption of more innovative HR strategies (Hanaysha & Tahir 2016). Organizations that managed to establish a proper degree of empowerment have higher chances to survive in the international market.

The key idea that underlies empowerment is that giving authority, resources, opportunities, and encouragement to employees (while making them liable for outcomes of their decisions) not only increases their job satisfaction but also leads to higher competence as they will be able to address issues that were previously beyond the scope of their duties. According to Gill et al. (2010), empowerment is intended to give workers an opportunity to make their choices and hold responsibility for their consequences.

There are numerous classifications of types of empowerment found in different studies. However, all of them can be reduced to five categories:

- Sharing information. This empowerment practice presupposes communicating important facts to the entire team and encouraging feedback. According to Mushipe (2011), the necessity to align with the changes in the business environment makes it crucial for companies to adapt their strategic programs in accordance with the feedback obtained from workers.

- Upward problem-solving. This implies that all organization’s problems must be solved collectively with employees. In the majority of organizations, this process starts from the top and moves down the hierarchy. Yet, empowerment presupposes that employees can solve a number of work-related issues, improve work processes, and propose innovative solutions without having to receive special permission. Self-managed groups of workers are liable for their decisions and can appoint their own leader within the team to govern the process (Hanaysha & Tahir 2016).

- Autonomy of tasks. It is a common practice to divide tasks among employees, who specialize in a particular sphere. However, when their competence and knowledge are boosted, they feel more confident in task autonomy and can perform more than one piece of a big assignment, gradually becoming capable of completing the entire task (Zhang & Zhou 2014).

- Attitude shaping. Empowerment is seen not only as physical but also as a psychological process. Owing to the rapidly changing environment, there are plenty of modifications of organizational structures and strategies, which can face resistance on behalf of employees. In order to avoid this, they must be empowered to express their opinions and attitudes. This type of empowerment also includes the ability to interact freely with colleagues and customers (Kim & Fernandez 2017).

- Self-management. The last type presupposes that employees should be given enough space to perform their duties and choose whatever methods they find necessary to maximize their productive potential (Mushipe 2011).

Whatever types of empowerment are named by scholars, they all agree on their extraordinary importance. The standard HR practices include recruitment, orientation, and training of employees for them to be able to achieve customer satisfaction. However, every organization must be sufficiently flexible to be able to release rather than limit, underuse, or totally neglect its workers’ prior knowledge and experience that had been obtained before they were hired. Employees’ activities must involve all their capabilities to achieve high-quality performance. Giving them the power to fulfill their potential is one of the key prerequisites for engagement. The success of the empowerment policy can be judged by its ability to create a win-win situation, in which employees are satisfied with their authority, and the company is made more productive. Ultimately, this should lead to increased customer satisfaction.

Thus, the information provided above can be summed up as four key points why empowerment is crucial for organizations:

- It fosters creativity. When employees feel valued, they are motivated to use creative approaches to complex situations, applying their unique skills, knowledge, experience, and way of thinking. Creative thinking frees top managers of the necessity to impose innovation as empowered employees do not need to be forced to introduce new practices and methods (Zhang & Zhou 2014).

- It increases job satisfaction. A relative autonomy increases employee satisfaction since they develop a strong sense of worth. Moreover, their inner sense of duty also becomes more profound as they feel that they must repay for the company’s trust and meet its expectations. Such workers provide better services thereby pleasing customers (Mushipe 2011). They also feel a personal responsibility for other members of the team and tend to support and guide them, which also contributes to job satisfaction.

- It gives workers decision-making power. Employees who are used to excessive reliance on the leader’s decisions cannot handle unexpected or unusual situations where no guidelines are in place to help them, or the leader is inaccessible and cannot provide clear instructions (Zhang & Zhou 2014). That is the reason such workers need to be empowered to develop their decision-making skills. Being equipped with the knowledge and encouraged to make decisions, they become more flexible and can address any customer needs regardless of the complexity of the situation (Ford 2014). The company will benefit from employees that are able to keep track of changes in the customer’s attitudes and preferences and find solutions to problems in accordance with the changing conditions.

- It ensures loyalty. Loyalty to the company appears when employees are listened to, supported, provided with training and career-building opportunities, valued, and trusted in their decisions (Hanaysha & Tahir 2016). When employees are empowered, they become better aware of organizations’ needs, values, problems, strategies, etc. They feel more closely connected to it, which makes them work harder to pursue its interests. This leads to higher service productivity and lower turnover rates (Ford 2014).

Organizational Learning Culture

Currently, many organizational studies are available that are dedicated to learning in the context of innovation. First of all, Egan, Yang, and Bartlett (2004) link organizational learning to the process of transferring knowledge in the workplace and argue that, if the process is well-established, and the employees are willing to engage in it because they recognize the benefits, it shows that the organizational learning culture is developing properly. The authors explored several other aspects of organizational performance and operation that can be affected by learning; particularly, it is claimed that ‘job satisfaction is associated with organizational learning culture’ (Egan, Yang & Bartlett 2004). Another aspect of the operation in which an organization can do better by developing its learning culture is a competitive advantage. In the context of entrepreneurship, (Barney, Wright, and Ketchen 2001) write that an ‘expanding knowledge base and absorptive capacity through experience and learning is key to achieving a [sustainable competitive advantage].’ Both the expansion of the knowledge base and what the authors refer to as the absorptive capacity are elements of the organizational learning culture.

Concerning competitive advantage, other authors suggested that innovations in the way organizations manage their operation and create opportunities for themselves can be much more effective in terms of gaining competitive advantages than what can be referred to as ‘strategizing’ (Teece, Pisano & Shuen 1997), which includes being engaged in active and possibly aggressive competitiveness. Learning plays a significant role in this process, which is why an indirect connection can be established between better learning practices and gaining remarkable competitive advantages. Also, one of the areas of research in terms of learning and innovation was the area of emerging economies. Yu et al. (2013) argue that, in such economies, certain strategies should be adopted by companies in order to achieve innovativeness and succeed ‘in a dynamic and turbulent environment.’ These strategies should be oriented toward entrepreneurship and technology; however, an important part of such strategies is the process of knowledge integration, and the authors list two major mechanisms of knowledge integration: organizational learning and a knowledge management system.

Further, many researchers analyzed the ways in which organizational learning cultures can foster innovation, i.e. particular mechanisms and processes. First of all, Huber (1991) explains that the crucial factor in improving organizational adaptation and innovation is gaining insight into how organizations learn and how they can learn better. In this context, organizations are seen as integral entities, and it is not employee training that the author refers to but the ability of an entire organization to improve through learning new things. A crucial process in this regard is ‘exposure to facts and findings from other research groups’ (Huber 1991); therefore, the more organizations are willing to constantly process research information and learn from it, the more likely they are to succeed. In terms of research, Chiva, Alegre, and Lapiedra (2007) suggest using research findings in the processes of innovation and learning, which they do not regard as separate but as intertwined components of ‘experimentation.’ Once methods of trying something new are designed, organizations are enabled to develop innovations and learn at the same time.

Among other mechanisms, Bates and Khasawneh (2005) suggest that the organizational learning culture can foster innovation through human resources practices; particularly, these include the creation of a proper psychological climate for transfer. What the authors mean by the concept of psychological climate is related to a set of specific characteristics of an organization in terms of how it treats its employees and customers and communicates with internal and external audiences. These characteristics may or may not be favorable for the employees’ willingness to interact meaningfully and transfer knowledge. It is suggested that the psychological climate for transfer should be positive and supportive, and an especially important role in it is played by the learners’ perception of the purpose of learning: they should recognize the potential benefits. Similarly, Song and Chermack (2008) argue that organizations’ interest in knowledge management, which is closely associated with the learning culture, has been growing due to the acknowledgment that innovation and better performance can be achieved through the use of it.

It is noteworthy that, in reviewing relevant literature, not only studies dedicated to the connection between organizational learning culture and innovation were examined, but also studies on innovation and studies on organizational learning separately in which the connection was revealed, too. For example, Dobni (2008) explains how innovation orientation can be managed and suggests 86 scale items; one of them is organizational learning that encompasses such considerations as ensuring that everyone in an organization is involved in training, the training is specific and related to strategic goals, and evaluation confirms that training helps deliver customer value. Similarly, Dombrowski et al. (2007) identified several categories of innovative cultures, and under one of the—collaboration—the organizational tactics should be to create cross-functional teams, develop the learning environment, and emphasize information and communication technologies.

The organizational learning perspective suggests that having creative employees who are eager to learn may not be enough for an organization to succeed in innovation. What is needed is a systematic approach that allows translating knowledge into practices on the basis of human, social, and organizational capital (Wright, Dunford & Snell 2001). Daft (1978) argues that innovations are initiated and promoted by experts in particular domains, and the intention in such cases is to make those experts’ work more effective or efficient. Therefore, learning should be not only specific but also advanced. Also, Knight and Cavusgil (2004) refer to the idea that learning ‘occurs best under conditions in which there are little or no existing organizational routines to unlearn.’ Therefore, the organizational learning culture should incorporate the flexibility of operation that will ensure that new knowledge can be applied, and the application of new knowledge should be encouraged.

Innovation

Innovation is one of the instruments that have been increasingly seen as an enabler for the organization to be unique and different. The economic booming and the high competition between organizations on the market these days will force them to come up with unique products and exceptional ways of providing services and faster processes to get the chance and compete in the market.

According to Alexander, Cleland, and Nicholson (2017), the highly competitive environment in nature needs creativity and that is the only tool that will let any organization compete in today’s market.

Increasing the effectiveness and outcomes of the business operation through the implementation of the latest technology is believed to be highly associated with innovation. Although enhancing the growth of the organization through technological development is greatly beneficial for their economic development, innovation and creativity can go broader than just the use of the latest technologies. Innovation is a phenomenon that has multidimensions which are based on the ability of the organization to solve problems preventively and predictively in addition to planning and implementing unique strategies to deal with the competitive environment taking into consideration the costs and resources efficiencies (Gaul 2016).

Although the concept is simple yet, innovative linked maximally with the need to deploy to the beneficial multiple critical factors. Firstly, the organization’s ability to take advantage of the opportunities in the niche market to expand and develop (Sahay & Gupta 2016). Hence it means that organizations are required to invest in tangible recourses which is human capital side by side along with the intangible recourses which is the financial capital to deploy innovativeness. Furthermore, it is important to frame the process of innovation. moreover, personal efforts may be playing a significant role in the personal innovative performance for the employee himself, instead of the company overall performance. In this manner, focusing on developing strategies for innovation as the hole will assure the cultivated overall employees’ performance to drive the organization toward accomplishing organizational objectives and direction (Sahay & Gupta 2016).

Moreover, it is critically important to put into consideration other types of innovation, such as services, products, and process innovation. So innovation is not just based on technological development but also focuses on other areas such as services, products, and process innovation (Tan & Nasurdin 2011).

Furthermore, the organization must set criteria and strategies in order to develop and improve the skills, knowledge, and abilities of their human capital which will reflect on the acquisition of new behaviors which will create the culture of the learning culture and foster innovation (Tan & Nasurdin 2011).

Human capital is the driving factor and the basis for establishing the culture of innovation in any organization (Michaelis & Markham 2017; Olsen 2017; van Uden, Knoben & Vermeulen 2017). Since it’s linked to the fact that any changes in any organization are created by people themselves if they were employees or leaders or even customers orientations and needs, so it is not possible to improve or develop or change any operations in the organization without their effort. Essentially, employees are the collective of the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that shape the company with their fulfillment of the organization’s operations and the achievements of the objectives and goals that have been set by the organization to reach their targets (Aguinis & Kraiger 2009). Innovative employees can be developed by putting into consideration multiple factors.

Firstly, their educational level which sometimes associated closely which the personal benefits of the training programs that are given to the employee (Tsai 2011; van Uden, Knoben & Vermeulen 2017). These Elements have been broken down into two components from several researchers, which linked to each other which is the educational level of the employee himself as an individual and the training that he gets from the organization so it’s a combination of both the individual and the organizational effort (McGuirk, Lenihan & Hart 2015).

Willingness is another element that affects innovation it can be a major element. Employee willingness is the keenness of the employee to cope with the changes in the organization and how he embraces these changes, also if the employee is willing to work hard to be one of the drivers of the company competitiveness since the organization is investing and spending on developing this employee (McGuirk, Lenihan & Hart 2015).

Finally, job satisfaction is also considered as one of the key elements in having innovative employees, the fact of having unsatisfied employees with their nature of work, organizational environment, or organizational culture that will reflect obviously on their performance (McGuirk, Lenihan & Hart 2015).

Elements presented above can be used to measure the innovativeness level of the employees in the organization which will help in the development fostering innovation.

Learning Culture and Innovation

According to Omerzel and Jurdana (2016), learning as culture refers to the sustained practice that encourages individuals and organizations to increase their knowledge and competence with the aim of improving their performance. The workplace environment is changing due to the changes in technology and socio-economic sectors. The knowledge and skills relevant today may not be relevant in the future (Ren & Zhai 2014). Emerging technologies are bringing about new ways of undertaking various tasks efficiently and effectively than before. Successful organizations understand the need to embrace continuous learning as one of the ways of remaining sustainable. As Murad and Kichan (2016) admit, change is often an undesirable force. People prefer doing things in a given pattern that they are used to irrespective of changes in the environment. Unfortunately, change is one of the external environmental forces that an organization cannot ignore. When a time for change beckons, organizations and individual employees often have to embrace it at all costs. However, change can only be embraced if an organization embraces a learning culture (Pruzan 2016). It makes it possible for the employees to acquire the new skills and expertise needed to work under the new system.

Learning culture and innovation are often intertwined. As Castro et al. (2013) state, innovation involves coming up with new better ways of undertaking the current or future responsibilities. It involves understanding the current or emerging needs and finding the best ways of meeting them using the available resources. Sayigh (2014) says that innovation requires constant learning. Through learning programs, individual employees get to challenge their current capabilities as they aim to put to practice the new concepts acquired. They get to view the problems faced in their organization from a different perspective that enables them to come up with a better solution. Sayigh (2015) says that employees that do not acquire new knowledge consistently sometimes even fail to understand the existence of problems within their organizations until it is too late. Such rudderless employees tend to be more of liabilities than assets to an organization. They can easily make serious mistakes with devastating consequences to an organization without understanding what they did (Parris 2016). Companies such as Google and Microsoft, having understood the importance of learning culture in promoting innovation, have set up learning centers within their campuses to help in empowering their employees (Westeren & Westeren 2012). These companies are making heavy investments in the training programs with the view of ensuring that the skills of their employees are always aligned with the job requirement (Mallakh 2015).

The Peculiarities of the State-Owned Enterprise

Scholars examined the peculiarities of the development of learning cultures in the setting of state-owned organizations. Researchers stress that Emirati state-owned companies often face numerous challenges when implementing changes due to their lack of flexibility (Harry 2016). However, it is also acknowledged that the companies that change and innovate become more successful as they achieve their organizational objectives in a more efficient way (Harry 2016). Researchers attempt to analyze the views of all the stakeholders involved but the major focus is on the perspectives of leaders and managers. There is also a lack of attention to specific experiences of companies, and the way employees saw the changes that were taking place.

Research Gaps and Justification

As it has already been mentioned in the previous section, although the concepts of innovation and a learning culture evoke much interest, scholars tend to focus on separate aspects rather than on the holistic picture. This narrow approach creates considerable gaps in understanding what a learning culture is and what factors predetermine its formation (Senge 2014). There are several clusters of issues that do not receive sufficient attention. All these gaps are associated with the exploration of specific approaches and methods in different types of companies.

The first one is connected with the path a company must follow to make the transition to creating a favorable learning environment. It is still hard to say if there is a trigger that can turn an ordinary organization into a learning one. Neither is it clear whether this process is natural and unintentional (resulting from the company’s success in other areas) or organizations must deliberately develop strategies to create a learning culture and appoint a person to carry them through (Tuggle 2016). The second cluster of research gaps relates to the nature of learning organizations since the majority of studies give only general descriptions of them (Tuggle 2016). The third group concerns the effect of favorable learning culture on innovation and the overall performance of the organization (Sessa & London 2015). The fourth cluster of gaps refers to various contextual factors that contribute to the formation of a learning culture (Sessa & London 2015). The final cluster of research gaps concerns sociological factors (Tuggle 2016). In other words, it concerns the influence of the company’s employees and leaders on the formation of the learning culture.

Making inferences from the above-enumerated gaps, it can be said that the present research is justified by the absence of clear goals of creating a favorable learning culture, vague understanding of reasons to do it, and encouragement required for making a successful transition. Most leaders and senior managers cannot set particular learning goals and metrics to assess their employees’ progress. Furthermore, a more thorough investigation is needed to understand what motivates workers to learn and implement new knowledge in practice. To put it differently, it is necessary to find out what empowerment tools are required to ensure engagement and to increase the effectiveness of training, transforming general goals into personal priorities.

As far as the empirical goals of the present study are concerned, the major objectives will concentrate on the needs and characteristic features of the state-owned enterprise. In order to narrow down the scope of this study, only the most urgent issues and concepts will be addressed. These concepts are closely related to the major factors affecting the development of the learning culture in a state-owned company. For instance, Harry (2016) states that peoples’ reluctance to innovate or even adopt new methods that have been seen as successful in other regions is one of the most considerable barriers to change. Employees of state-owned organizations tend to trust their peers’ experiences and views rather than learn and use new ways and approaches. At that, it is often unclear what is regarded as innovation and learning. Therefore, it is essential to explore people’s views on the matter.

One of the central areas to address is employees’ views on innovation, learning, and empowerment. It is important to identify specific attitudes and viewpoints. Employees of state-owned companies (especially management) tend to see learning as a straightforward transfer of certain knowledge (Tajeddini 2016). Learning often occurs in the form of lectures, seminars, and the like. This traditional approach also shapes people’s views on the learning culture and innovation (Harry 2016). The effective implementation of change may imply the development of new views and attitudes concerning learning, innovation, motivation, and commitment.

The analysis of these concepts will help in crafting an efficient change plan that can be applied to state-owned companies. The plan will aim to develop the learning culture that will foster innovation in the organization. The program’s effectiveness can be ensured by the fact that all employees’ needs and concerns will be taken into account. The present research will attempt to voice the needs and expectations of employees at different levels of a state-owned organization. Therefore, it is possible to develop a program that will be positively seen by the stakeholders, and the change will be embraced in a more effective way.

Tajeddini (2016) examines the most pronounced effects of the implementation of the learning culture and the focus on innovation in the context of state-owned enterprises. The researcher emphasizes that this framework translates into considerable improvements associated with employees’ performance and the quality of the services that are provided. It is noted that organizations that aim at innovation and learning often face some challenges including employees’ resistance. Hence, it can be important to identify primary barriers to the adoption of this approach in a state-owned organization as viewed by employees at different levels. The areas to pay attention to can be motivation, tools, and methods used to develop the learning culture, expected outcomes, and so forth.

Finally, the present research will also identify specific expectations of the stakeholders mentioned above. It is important to understand what outcomes people expect to see after the development of the learning culture. Moreover, it can be beneficial to elicit employees’ views on the process of change and their gains or losses at different stages. This information can be instrumental in the development of achievable goals and objectives when working on the change plan. It will be possible to predict the areas of major concern or resistance as well as develop effective strategies to address them.

Methodology

Research Problem

The present study aims at examining the attitudes of employees working at different levels towards the factors that affect the creation of the learning culture as well as its impact on the promotion of innovation culture within the context of an Emirati state-owned organization. The employees will share their perspectives on the nature of learning and innovation culture as well as any barriers or challenges that can arise. They will also provide their perspectives concerning motivation, engagement, empowerment, and training. The participants will try to identify the associations between the concepts mentioned above. The views of seniors and their subordinates will be analyzed and compared. The participants will be encouraged to contemplate the practices existing in their organization as well as some areas for improvement.

It is pivotal to ensure the free sharing of views and concerns, which can be achieved through the use of interviews. The employees of a state-owned organization will try to reflect on certain issues and contemplate their attitudes and behaviors. It is assumed that some challenges to the development of learning and innovation cultures will be identified. The employees’ accounts will be analyzed in detail to evaluate the difference between the perspectives of seniors and their subordinates as it can eventually help in the development of the interventions aimed at the creation of innovation culture.

Research Philosophy

Before discussing the research design, it is necessary to identify the research philosophy used as a framework for this study. It is pivotal to make sure that the research is guided by a specific research philosophy, which can help the researcher to develop an effective research design and instruments (Antwi & Hamza 2015). The suggested research is qualitative in nature as it concentrates on people’s attitudes towards certain concepts and phenomena. The guiding research philosophy of this study is interpretivism as the primary focus is on meanings and interpretations rather than trends and quantitative analysis.