To be successful and efficient, the army should be organized around the strong principles that determine the way how roles are distributed among soldiers. The two most important roles, without which an effective army cannot exist, are followers and leaders. Although these groups have distinctive functions and objectives, these roles are interconnected with each other. Followers and leaders work in symbiosis by defining the main areas of attention and improvement for both sides. Therefore, followers and leaders are not placed in a strict hierarchical order. In contrast, they work and communicate together based on equal rights to improve the quality of army functioning.

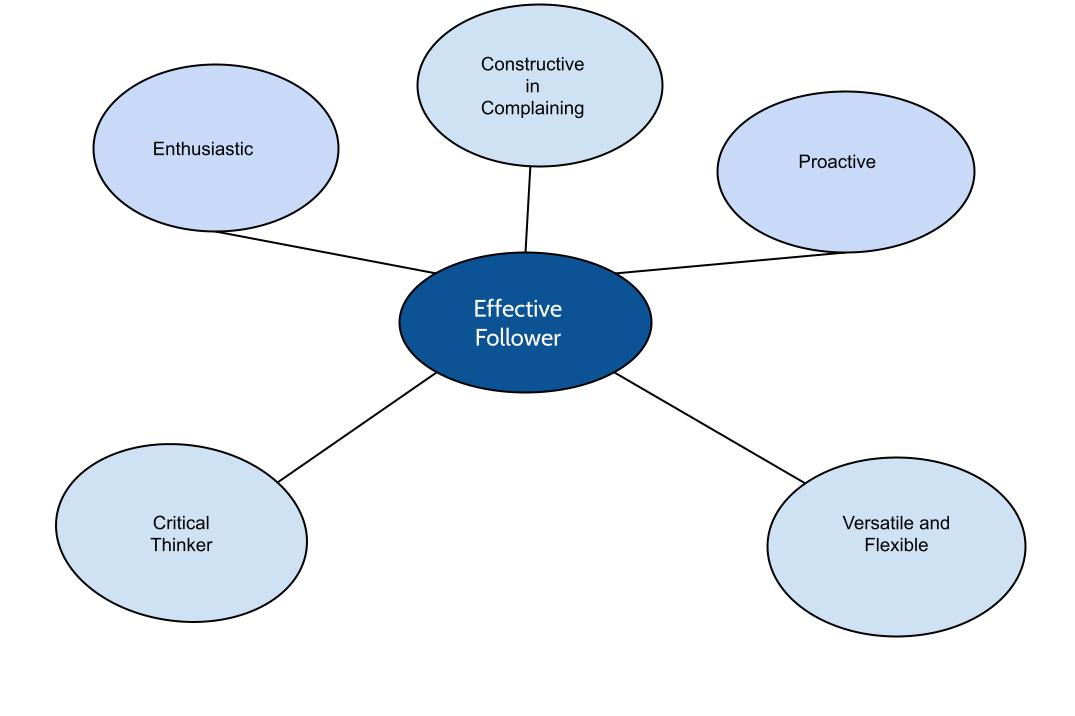

In an effective army, followers are not loyal sheep who follow all the orders of the leaders, but highly qualified participants in a two-way communication process that requires certain skills. Firstly, it should be noted that followership skills are not located in subordination to leadership and are not a subset of leadership. Leadership and followership are ”the two sides of the same coin” (Corrothers, 2009, p. 3). A clear understanding of what qualities true followers should have can be formulated through Kelley’s model of follower behavior (Kalimuddin, 2017). It tells that the best followers must have independent and critical thinking and be active in decision-making. Another implication from that model is that followers should not be sheep or “yes people.” It raises the importance of constructive complaints, which can bring some qualitative change and improvement in army management.

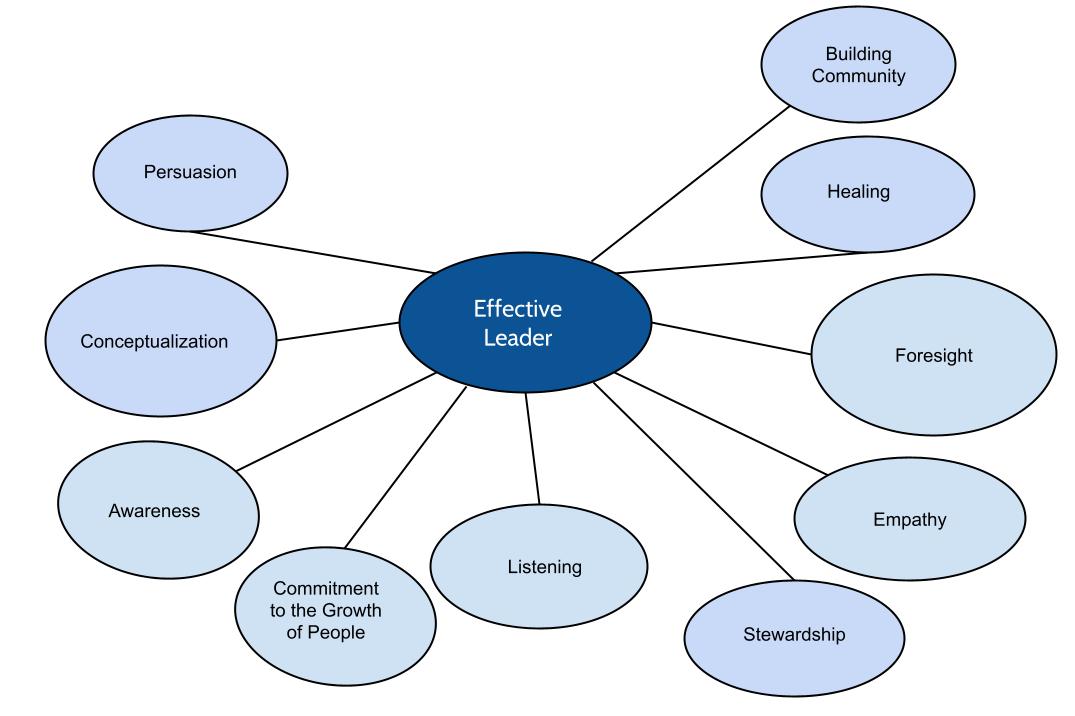

The scholarship on army leadership is highly influenced by the concept of “servant leadership,” coined by Robert K. Greenleaf in 1970. The main meaning is that army leader should not be “tyrants” who put first their high place in the army hierarchy. Instead, they need to set aside their egos and focus on the needs and demands of their followers (Griffing, 2019). According to Griffing, servant leadership prioritizes the value of listening, empathy, healing, awareness, persuasion, conceptualization, foresight, stewardship, commitment to the growth of people, and building community. These characteristics proceed from US democratic values that prioritize greater morals and a fair attitude toward each member of the army. In metaphorical words, leaders have a second set of eyes that are designated for monitoring followers’ moral and health conditions. Thus, the concept of servant leadership underscores the value of reciprocity and interaction between different army groups to achieve a more elaborated system of management.

Comparing and contrasting these two army roles, one can find specific similarities between followership and leadership. The main similarity is that leaders and followers are committed to the same army values. These values are loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage (U.S. Army, n.d.). The proper adherence to such values prevents the possibility of unfair and derogatory attitudes of leaders toward followers. These values emphasize the respectful and equal relationship between groups of different army levels. Thus, followership and leadership are linked concepts, which means that the absence of one role leads to the non-existence of another side. However, the difference is that these two groups are special roles with certain obligations and goals. These roles should be considered functionally, that is, as part of one efficiently working mechanism. Therefore, leadership does not create a certain privilege that puts them in higher social status than followers.

To sum up, the concepts of leadership and followership explain what an effective army structure should look like. Effective leaders should be good followers, and good followers should have effective leadership skills. The main idea is that there should be an understanding of the necessity to possess both roles in the army. Therefore, the US army operates based on democratic values, where army positions are just roles but not markers of privileged social standing.

References

Corrothers, E. M. (2009). Say no to “yes men”: Followership in the modern military. Air command and staff Coll Maxwell AFB AL. Web.

Griffing, M. S. A. L. (2019). Servant leadership. Army University Press.

Kalimuddin, M. (2017). The practical application of followership theory in mission command. Military Review, 1.

U.S. Army. (n.d.). The army values. Web.

![]()

![]()