Abstract

Opportunity recognition process is to be considered as important one among the different aspects in the path to entrepreneurship. This process follows a definitive flow of events starting from generation of ideas, shaping them into workable opportunities and developing them into profitable business ventures. There is the need to distinguish between ideas and opportunities in the whole process. Literature has identified a number of factors influencing the process which include creativity, optimism, information search, alertness, social networking and prior knowledge. Based upon the presence of some of these personal traits and by adapting to the circumstances, entrepreneurs are able to work their ways to recognizing profitable ventures and convert them into operable business ventures. However the question remains as to which are the ones out of these factors contribute most to the opportunity recognition process of the entrepreneurs. The objective of the study was to examine the relative impact of these factors on the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition process. The explanatory investigation is based upon the theory of opportunity identification process advocated by previous researchers. Using the quantitative method of questionnaire survey among 42 entrepreneurs owning high-growth business ventures, this study purported to examine the influence of the factors affecting the opportunity recognition process among the entrepreneurs and to make an analytical review of the influence of respective factors on the opportunity recognition process. The findings from the survey reveal that the quality of alertness and the prior knowledge of the entrepreneurs are the most influencing factors in the process of opportunity recognition. This study has disproved one of the earlier findings that social network is among the most influencing factors of the process. This study was built on previous theoretical and empirical works and a theoretical model which effectively explain the factors influencing opportunity recognition process with a discussion on implications, limitations and recommendations for further research on the realm of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition.

Introduction

There are varying definitions of entrepreneurship (e.g., Kirzner, 1973; Schumpter, 1934; Stevenson et al., 1989; Vesper, 1996) which portray the common feature of entrepreneurship as the act of creating a new venture (Gartner, 1985). This leads to the identification of ‘recognition of opportunity’ as one of the major components of any entrepreneurial activity (Hills, 1994). Thus entrepreneurship can be regarded as the process of creating value by integrating the resources for exploiting an available opportunity. From this it can be derived that an entrepreneur is “someone who perceives an opportunity and creates an organization to pursue it” (Bygrave & Hofer, 1991, p 14). Timmons, (1994) has identified three crucial driving forces of entrepreneurship which include (i) the entrepreneur or founder, (ii) the recognition of opportunity and (iii) the resources needed to found the firm. The process of entrepreneurship is complicated with the existence of various other factors such as risk, chaos, information asymmetries, resource scarcity, uncertainties, paradoxes and confusion. Successful entrepreneurship can be developed only when all the three components are arranged in a proper fit. An entrepreneur has to face the challenge of manipulating and influencing the factors affecting the process of entrepreneurship so that he can improve the chances of success of the venture. Since opportunities seldom wait, right timing of the recognition of the opportunity becomes critically important for any entrepreneur. In this context this research examines the factors that influence the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition process amongst high growth, start-ups companies in the Irish economy.

Entrepreneurial Process and Opportunity Recognition – an Overview

Shane & Venkataraman, (2000) define entrepreneurship as an activity that involves the discovery, evaluation and exploitation of opportunities to introduce new goods and services, ways of organizing markets, processes and raw materials through organizing efforts that previously had not existed.

The entrepreneurial process begins with the perception of the existence of opportunities, or situations in which resources can be recombined for a potential profit. Van de Ven et al., (1984) states that a major topic of entrepreneurship research lies in the way individuals recognise opportunities for creation of business ventures. Christensen et al., (1989) define opportunity recognition as perceiving a possibility for new profit potential through (a) the founding and formation of a new venture, or b) the significant improvement of an existing venture. Shane, (2003) suggest two main reasons why one person might discover an opportunity before others, first because they have better information, and secondly they are able to put a given item of information to better use or to put it differently they are able to construe it more effectively. Vesper, (1993) makes a distinction between two different types of opportunities; (i) a business opportunity and (ii) a new venture opportunity. The difference can be inferred from the fact that a business opportunity is one in which an entrepreneur who owns an established business recognizes an opportunity for enhancing the profit potential whereas, a new venture opportunity is one that which is an attempt to take advantage through the founding of an independent new venture. Although these distinctions are inclusive of different conceptions of entrepreneurial opportunities, this paper will focus on the ‘new venture opportunities’.

For a comprehensive presentation of this analytical review, it is necessary to perceive the magnitude of chances in the industries with differing nature. In a high-growth industry where the entry barriers are comparatively less, it is easier and better to enter the market. There would be no need to undertake an extensive strategic planning process before launching any new venture, since one can find an abundance of opportunities (Teach et al., 1989). Moreover, such an industry is not so densely populated (Hannan & Freeman, 1977), since it has a high carrying capacity with no need to be a specialist to enter the market (Lambkin, 1988; Romanelli, 1989).

On the other hand, in mature industries a process of selective screening and identification of right opportunities might lead to successful venture creation. Even with significant entry barriers, one can find niche opportunities in the mature industries also. Therefore recognition of the opportunities at the right time becomes critical though not an absolute necessity as opportunities always present themselves.

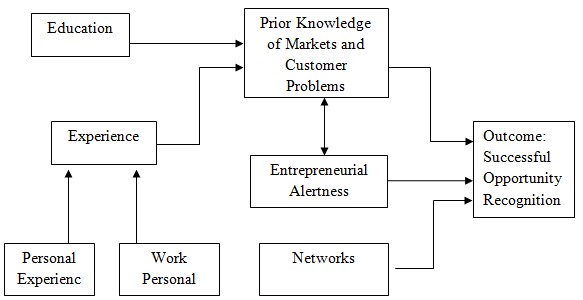

The knowledge and experience of the individual entrepreneur is one of the major forces in recognizing the opportunities for any new venture. Prior knowledge could have been accumulated out of the education and experience in which the experience might be work-related or is the result of a number of personal experiences and events. It is vitally important that the entrepreneur has the ability to recognize that he possesses such knowledge and experience and use this in recognizing the opportunities. The entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial networks are the other important factors which influence the opportunity recognition process. Entrepreneur’s prior knowledge on the customers’ problems and market characteristics and entrepreneurial alertness has a close interaction which tells upon the ability of the entrepreneur to recognize new and profitable opportunities. The ability of the entrepreneurs to identify meaningful business opportunities automatically places them in a strategic position to successfully launch new ventures. Significant research has been carried out on the process of opportunity recognition and as a result of the research several models have been developed. One of the models which clearly identify the different aspects of opportunity recognition process is presented below:

In Ireland, as in countries across the OECD and Europe, the majority of entrepreneurs starting a business do not expect their new business to grow to a large size. The small numbers of businesses that do grow significantly, however, make a disproportionate contribution to employment growth (GEM Report 2007), for the purpose of the dissertation this study shall focus on high growth expectation early stage entrepreneurs defined as those early stage entrepreneurs expecting to employ twenty or more staff within five years (definition form GEM 2007). This will exclude lifestyle firms, i.e. businesses that are setup to undertake an activity that the owner-manager enjoys or get some comfort whilst providing an adequate income, e.g. craft based businesses (Burns, 2001).

Significance of the Study

Gaglio, (1997) remarks that academic interest in opportunity identification and creation has arisen because of its unique position in the context of business ventures, something entrepreneurs do while non-entrepreneurs do rarely, if at all. Fiet (1996) notes that scholars generally study what entrepreneurs do after discovering a venture opportunity and completely neglect the subject of new venture ideas. Taking this approach, the risk of the venture is associated with the uncertain success of implementing a business plan. However, risk also attends the choice of the type and means for acquiring information to make the initial discovery of the opportunity. Similarly Plummer et al., (2007) concludes that there is a notable lack of research focused on the origins of opportunity, and the disparate nature of the propositions suggested in response to the question of where opportunities originate, is not surprising.

The number of entrepreneurs in Ireland was increased by 2,700 individuals setting up new businesses each month, throughout Ireland in 2007. Responding to opportunities, many of these entrepreneurs are motivated by a sense of independence that being their own boss confers. Some would find opportunities to create jobs for themselves; the majority however, will become employers. A small number will go on to create large businesses (Mary Coughlan T.D. Minister for Enterprise, Trade and Employment in Entrepreneurship in Ireland 2007 GEM Report)

The impact of high growth firms is broader than employment creation, however. Because of their strategic focus on maximising a perceived opportunity for commercial growth and wealth generation, high growth enterprises are by nature, innovative in products, services, and/or markets and are a major contributor to the diffusion of technology and the commercialisation of research. Innovative firms of this nature also exert pressure on existing established firms, as the latter are forced to adapt if they are to survive (Forfas, 2007). Several empirical studies confirm the importance of high-growth firms for job creation. The first GEM global report on “high-expectation entrepreneurship” (Autio, 2007) showed that high-aspiration entrepreneurs representing less than 10% of the population of nascent and new entrepreneurs, were responsible for up to 80% of total expected job creation by all entrepreneurs.

For a comprehensive presentation, the paper is structured to have different chapters. The introductory chapter gives an insight into the topic under study. Chapter 2 will present a review of the relevant literature to extend the knowledge of the readers on the subject of entrepreneurial opportunity recognition process. Chapter 3 deals with the aims and objectives of the study followed by chapter 4 detailing the research methodology. Chapter 5 includes the findings of the research and a detailed discussion on the findings and some concluding remarks are presented in chapter 6.

Literature Review

Baron, (2006) defines opportunity recognition as the cognitive process (or processes) through which individuals conclude that they have identified an opportunity. Opportunity recognition for new business ventures is an important dimension of the entrepreneurial process (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000; Baron & Ensley, 2006; Casson & Wadeson, 2007; Alvarez & Barney, 2007). The belief of a person that he/she has recognized an opportunity with potential for earning profits would lead to a decision to found a new venture (Gaglio & Katz, 2001; Baron, 2007). There have been wide ranging literature focusing on unravelling the antecedents of opportunity recognition. There are different factors that influence opportunity recognition. These include social networks (Singh et al., 1999; Baron & Ozgen, 2007), prior information (Shane, 2000; McKelvie & Wiklund, 2004), pattern recognition (Baron, 2006; Baron and Ensley, 2006) and entrepreneurial alertness (Kirzner, 1973; Gaglio & Katz, 2001). Based on this theoretical framework and a study of books and articles from academic journals this review has been prepared for enhancing knowledge on the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition. This review focuses on the following general theme of the material on opportunity recognition:

- Entrepreneurial Alertness and Opportunity Identification

- Prior Knowledge and opportunity Identification

- Social Networks and Opportunity Identification

- Accidental vs. purposeful search in the opportunity recognition process

- Model of opportunity recognition

Entrepreneurial Alertness and Opportunity Identification

Alertness, emphasizes the fact that opportunities can sometimes be recognised by individuals who are not actively searching for them, but who possess “a unique preparedness to recognise them…” when they appear. Kirzner, (1973) defined it as “alertness to changed conditions or to overlooked possibilities.” This definition suggests that opportunities can be noticed even by persons who are not actively seeking them; indeed, when alertness is high, entrepreneurs may engage in what has been termed “passive search,” a state in which they are receptive to opportunities, but do not engage in a formal, systematic search for them (Baron 2006)

Casson & Wadeson, (2007) equate Kirzner’s definition of entrepreneurial alertness to suggest that opportunities are like dollar bills blowing around on the sidewalk, waiting for an alert individual to pick them up. This view is supported by Gaglio & Katz, (2001) whom observe that almost all of the initial empirical investigations of alertness have focused on the means by which an individual might literally “notice without search.”

However Busenitz, (1996) disagrees with the theory of alertness, which asserts that entrepreneurs are more alert to new opportunities and use information differently. And states that “his research results indicate that little empirical support exists for this theoretical framework, but the measures of entrepreneurial alertness need further development.

The basic concept in Kirzner’s (1973) theory of entrepreneurship is alertness. Alertness leads individuals to make discoveries that are valuable in the satisfaction of human wants. The role of entrepreneurs lies in their alertness to hitherto unnoticed opportunities. Through their alertness, entrepreneurs can recognize and make use of situations in which they would be able to realize high prices for the articles which they can procure at lower costs.

An opportunity exists only if an entrepreneur perceives it. Even the most obvious opportunity can be ignored by a person who is not motivated to see it. In other words, individuals will not discover any profit opportunity if they “switch off” their alertness system. Given the significance of entrepreneurial alertness it is desirable to have an inquiry into its nature.

Kirzner, (1997) refers to entrepreneurial alertness as “an attitude of receptiveness to available, but hitherto overlooked opportunities”. The entrepreneur has an extraordinary sense of “smelling” opportunities. Alertness is like an “antenna that permits recognition of gaps in the market that give little outward sign” and entrepreneurs always position themselves on the high ground where signals of market opportunities can more easily strike them. It is the self-interest motive that enhances the entrepreneur to be alert. In the cognitive perspective, this is called selective entrepreneurial attention (Gifford, 1992). Entrepreneurs never know that they posses ‘a resource of alertness’ in the sense that they are not conscious of their alertness. Nor do they know this resource is at their disposal (Yu, 1999). Alertness emphasises the fact that opportunities can sometimes be recognised by individuals who are not actively searching for them, but who possess “a unique preparedness to recognise them” when they appear (Gilad et al., 1989). Kirzner, (1985) who first introduced this term into the entrepreneurship literature defined it as “alertness to changed conditions or to overlooked possibilities”. This definition suggests that opportunities can be noticed even by persons who are not actively seeking then; indeed, when alertness is high, entrepreneurs may engage in what has been termed “passive search” a state in which they are receptive to opportunities, but do not engage in a formal, systematic search for them (Baron 2006)

It has been suggested that alertness rests, at least in part, in cognitive capacities possessed by individuals- capacities such as high intelligence and creativity (Shane 2003). These capacities help entrepreneurs to identify new solutions to market and customer needs in existing information and to imagine new products and services that do not currently exist (Barron 2006)

Pattern recognition is the process through which specific persons perceive complex and seemingly unrelated events as constituting identifiable patterns. Pattern recognition, as applied to opportunity recognition, involves instances in which specific individuals “connect the dots” –perceive links between seemingly unrelated events and changes (Baron, 2006). Alertness refers to the capacity to recognise opportunities when they exist- when they have emerged from changes in technology, markets, government policies, competition and so on (Baron, 2006).

Kaish & Gilad, (1991) found that entrepreneurs heightened their alertness to possible business opportunities by using different types of information to project the potential of new business opportunities. Busenitz, (1996) conducted an empirical test of Kaish & Gilad, (1991) proposition that entrepreneurs are more alert to new opportunities and use information differently than managers do. Busenitz, (1996) found little empirical support for Kaish & Gilad, (1991) theoretical framework, and emphasised that the measures of entrepreneurial alertness needed further development.

Ray & Cardozo, (1996) argue that a higher degree of awareness towards soliciting and perceiving information exists in any prospective entrepreneur prior to recognizing the opportunities. Such awareness is a quality to perceive and remain alert to information about different elements in the environment, with enhanced awareness to the consumer needs and preferences, moves by different manufacturers and use of products. Ardichvilli & Cardozo, (2000) suggested that the concept of awareness can be used interchangeably with alertness. (Casson & Wadeson, (2007) equate Kirzner’s, (1973) definition of entrepreneurial alertness to suggests that opportunities are like dollar bills blowing around on the sidewalk, waiting for an alert individual to pick them up. This view is supported by Gaglio & Katz, (2001) whom observe that almost all of the initial empirical investigations of alertness have focused on the means by which an individual might literally “notice without search”.

In some instances, as alert entrepreneurs assess changing circumstances, they feel they cannot ignore or discount what is happening and come to realize that it is no longer a question of optimal resource allocation but really a question of whether the existing way of doing things (i.e., the existing causal chain or the existing means-ends framework) still works. Kirzner, (1979) considers this realization, hereafter referred to as “breaking the existing means-ends framework,” to be the quintessential entrepreneurial behavioural. When appropriate, alert entrepreneurs are willing to abandon the existing means-ends framework and develop new ones that represent their best guesses about the future. These guesses or visions, are realized as innovative products, services, or processes that then compete with existing products, services, and processes (i.e., the existing means-ends framework) as well as with alternatives offered by other entrepreneur (Gaglio, 2004).

A second way in which affect may influence opportunity recognition is by acting as a moderator of factors known to influence opportunity recognition. Two such factors are alertness and active search for opportunities. Alertness refers to “unique preparedness to recognize opportunities” when they appear (Gilad et al., 1989: 48; see also Kirzner, (1979); (Baron, 2008). Shane (2003, p.250) maintains that the “entrepreneurial process begins when an alert individual discovers those opportunities” (emphasis added). There is scarcely any substantive content rendered to the creative entrepreneurial discovery process itself except that it involves a “conjecture” on the part of an entrepreneur that a possible profit opportunity exists in a specific situation (Eckhart & Shane, 2003: pp. 338-339).

A key proposition is that all profit opportunities are not in fact “out there” and external to the entrepreneur waiting to be found by alert individuals possessing given prior knowledge. That entrepreneurs perform unique mental operations in creating opportunities is still an open question calling for greater investigation. The problem has lately been reflected upon by some researchers in the field who have related their findings to a range of disciplines (Minniti, 2003; Woods, 2002; Ward, 2004).

Mises, 1949, p. 92) made the “meanings and actions” of individuals the centrepiece of subjectivist economics. Individuals attach subjective meaning to their actions and express these in terms of purposes, perceptions, plans, valuations and expectations. For von Mises, (1949), the objects of entrepreneurial behaviour are not precisely “definable except in terms of which… [entrepreneurs] perceive them to be”. Alertness can be construed as a defining characteristic of entrepreneurial behaviour. The alert entrepreneur originally described in Kirzner (1973; 1979) has been widely discussed in modern literature (e.g. (Harper, 2003; Minniti, 2003; Shane, 2003; Endres & Woods, 2006). Alert entrepreneurs discover profit opportunities and the resources to exploit them; they are able to absorb details of the market by utilising an innate capacity to recognise opportunities without costly search and spontaneously and costless encounter “knowledge of where to find market data” (Kirzner, 1973, p. 67). Specific market data will signal to entrepreneur’s opportunities to earn a profit. Kirznerian entrepreneurs gain knowledge simply by “opening their eyes and discovering economic facts that had previously been overlooked by all other market participants” (Harper, 2003, p. 24). This conception of knowledge is rudimentary; it is consistent with profit opportunities that are just found in the present rather than being actively created by imaginative, attentive minds.

The process of creating opportunities Entrepreneurs are furnished with definite prior knowledge of objective opportunities derived in a process of gathering information from various sources including personal influence, business experiences, events, specific and specialised skills. Only alert individuals will be able to add to their stock of prior knowledge and successfully recognise and pursue opportunities. Nonetheless, all this begs the question: how are opportunities constructed in the minds of entrepreneurs? Furthermore, what internal subjective or general psychological forces are responsible for the construction process?

There is a strong case for more subjectivist research on entrepreneurial creativity – both theoretical and applied. A subjectivist perspective concentrates attention on a neglected question: how do some people create opportunities? This question is missing from the three central questions posed by Baron, (2004, p. 237, Table 2) for organizing research on entrepreneurial behaviour – that is, why some people become entrepreneurs, why some people and not others recognise opportunities, and why some entrepreneurs are more successful than others. We have shown that it may be fruitful for researchers to take a subjectivist perspective in reformulating the alertness concept originally developed by Kirzner who followed the ideas of von Mises, and complementing this with insights from recent developments in psychology. That way researchers will retain an essentially subjectivist proposition – that the principal subject matter in the entrepreneurial process is constituted by subjective, mental phenomena. Taking a subjectivist perspective on entrepreneurial creativity yields some key findings from the literature: entrepreneurs structure their existing knowledge of market environments; entrepreneurial “alertness” is best conceived as a behavioural propensity involving endogenous knowledge generation through a process of problematizing; in creating opportunities entrepreneurs develop new means-ends frameworks by testing conjectures – like scientists they conduct experiments in their environment; and entrepreneurs create opportunities in a flow of effortless activity which is fast, intuitive and quite spontaneous

Prior Knowledge and opportunity Identification

Austrian economics argues that different people will discover different opportunities in a give technological change because they possess different prior knowledge (Venkataraman, 1997). This viewpoint is supported by Shane, (2001) “given that information asymmetry is necessary for entrepreneurial opportunity to exist, everyone in society must not be equally likely to recognise all opportunities” whom goes on to hypothesize that all individuals are not equally likely to recognise a given entrepreneurial opportunity.

Shane (2001) proposes that three major dimensions of prior knowledge are important to the process of entrepreneurial opportunity identification: prior knowledge of markets, prior knowledge of ways to serve markets and prior knowledge of customer problems. Past research has shown that prior knowledge increases the likelihood of opportunity identification for two reasons (1) prior knowledge provides an absorptive capacity that facilitates the acquisition of additional information about markets, production processes and technologies (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) , which triggers an entrepreneurial conjecture (Shane 2000, 2003); and (2) people’s existing stocks of information also influence their abilities to see solutions when encountering problems that need to be solved (Yu, 2001). According to Shane (2000), people have different stocks of prior information through their life experiences that increase the probability of identifying opportunities. Life experiences can be in the form of job function, variation in experience and special interest (Shane 2003). An exposure to diverse life and work experiences broadens individuals’ range of what they perceive as feasible for an opportunity (Krueger & Norris, 2000). However, at any given time, only some people and not others identify certain opportunities. This phenomenon, in particular, exists in accordance with Ronstadt’s, (1998) Corridor Principle- once entrepreneurs found their firm, its sets off a journey down a corridor, through which windows of opportunity will open up around them. In other words, entrepreneurs would not see these opportunities if they had not entered the corridor- in the form of founding a firm in any particular industry.

Shane (2000) identifies three major dimensions of prior knowledge as important to the process of entrepreneurial opportunity identification: (1) prior knowledge of markets, (2) prior knowledge of the ways to serve markets, and (3) prior knowledge of customer problems. Prior knowledge of markets enables people to understand demand conditions, facilitating opportunity identification (Shane, 2003). Prior knowledge of how to serve markets also helps identify opportunities because people know the rules and operations in the markets (Shane, 2003). In particular, it helps determine the production or marketing gains from introducing a new product or service. Prior knowledge of customer problems or needs increases the likelihood of opportunity identification because such knowledge would help trigger a new product or service to solve the customer problems or to satisfy their unmet needs (Von Hippel, 1988).

Several empirical studies have shown support for the argument that prior knowledge increases the likelihood of identifying opportunities. Christensen & Peterson, (1990) examined the sources of new venture ideas using four structured case studies with fifteen ventures and a survey of 76 firms, and found that specific problems and social encounters were often sources of venture ideas while profound market or technological knowledge was a prerequisite for venture ideas. Young & Francis, (1991) conducted an exploratory study of 123 small firms in New York and found that 82 per cent of the founders had worked in a company producing the same or a similar product to the one produced by their own venture; 40 per cent of the founders even reported that their original product was the same as their former company’s product. Having personal experience and knowledge of an industry allows an individual to identify market needs and most importantly, assess the potential benefits and costs of serving those needs. As prior knowledge is idiosyncratic in nature, no two persons share all of the same information at the same time, resulting in information asymmetries, and therefore those who have better access to information are able to identify entrepreneurial opportunities (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). However, prior knowledge, like social networks, would have become useless if an individual had failed to process the information received from these sources cognitively, without which it is impossible to identify entrepreneurial opportunities. This is the role of cognitive properties of an individual that comes into play.

Entrepreneurial opportunities exist because all people do not possess the same information at the same time (Kirzner, 1997). In fact Kirzner, (1997) observed that in case of incomplete information in any market transaction entrepreneurs have to guess each other’s expectations about many things. Since these guesses may be incorrect as they are usually based on hunches, intuition, heuristics, and accurate or inaccurate information, errors are made to misallocation of resources (Schumpeter, 1934).

Hayek, (1945) argued that people tend to identify opportunities related to information they already have. Therefore, the most valuable information is that which relates to the special circumstances of the time and place of a specific transaction. In addition, people possess different stocks of information because specialised information is preferred over general information. This leads people to invest in the acquisition of specialised information that they do not have. Thus, only a few people know about a particular way to create new products or services, changes in the market, or specific customer problems. Fiet, (1996) observed that previous experiences set the context within which entrepreneurs decide to invest in a particular venture. Thus, it serves as a cue that alerts entrepreneurs to act. A great number of ideas came from previous employment followed by learning from other people. Therefore, to identify an opportunity, an entrepreneur needs to have prior knowledge that is complementary with new information and which triggers an entrepreneurial conjecture (Kaish & Gilad, 1991).

Prior knowledge of ways to serve markets can take many forms (Shane 2000). For example, a new system or technology can change production processes, allow for creation of new products, provide a new method to serve markets, permit new materials to be used, generate new sources of supply, or make possible new ways of organising production (Schumpeter, 1934).

Aldrich & Wiedenmayer, (1993), who reported that positive relationships exist between forms of new organisations and the products or service lines which an entrepreneurs establish and organisations in which they previously worked. Many entrepreneurs start new ventures that solve customer problems that they identified when working with users in their previous jobs.

To summarise, prior knowledge whether acquired through work experience, education, or other ways, influences an entrepreneur’s ability to comprehend, extrapolate, interpret, and apply new information in ways that those lacking that prior information cannot replicate (Shane, 2000).

Shepherd & DeTienne, (2001) found that in the presence of prior knowledge, a strong intrinsic motivation is aroused and is the primary incentive that “switches on” alertness, with possible financial reward (extrinsic motivation) less motivating. Further, financial reward was having only a less serious appeal for those who could perceive the customer problems intricately. Perhaps it was the aversion of those people with the stagnation, arising from better knowledge of market situations. In fact such advanced knowledge appears to be the prime motivator in any entrepreneurial recognition process.

Social Networks and Opportunity Identification

Arenius & DeClercq, (2005) argued that social encounters between an individual and her network contacts may be an important source of new ideas. Networks have also been linked with the number of new opportunities perceived by entrepreneurs (Singh et al., 1999). The rationale is that an individual’s network can provide access to knowledge that is not currently possessed, thus leading to the potential for opportunity recognition

An important way that people gain access to information is through interaction with other people. Therefore, one of the ways that people gain access to information about entrepreneurial opportunities is through their social network. The structure of a person’s social network will influence what information they receive, and the quality, quantity and speed of the receipt of that information (Shane 2003). Diverse social ties-or ties to a wide variety of people –should encourage access to information that facilities opportunity discovery. Much of the important information for discovering opportunities – information about locations, potential markets, sources of capital, ways to organise- is likely to be spread across a variety of people (Shane 2003).

Hill et al (1997) states that an entrepreneur’s social network can help expand the boundaries of rationality by offering access to knowledge and information not possessed by the individual entrepreneur and describes entrepreneurs’ personal social networks as the “most significant resource of the firm.”. And concludes that the findings of their survey show support for the importance of self perceived alertness and social network characteristics to the opportunity recognition process.

Eckhart & Shane, (2003) state social network theorists postulate that individuals uncover information through the structure and content of the relationships with other members of society (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1992). The structure of social relationships determine the quantity of information, the quality of information, and how rapidly people can acquire information necessary to discover opportunities for profit. According to Shane (2003, p. 49) an important way that people gain access to information is through interaction with other people. The structure of a person’s social network will influence what information they receive, and the quality, quantity and speed of that information. In particular, diverse social ties- or ties to a wide variety of people – should encourage access to information that facilitates opportunity discovery (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). Much of the information for discovering opportunities- information about locations, potential markets, sources of capital, employees, ways to organise- is likely to be spread across a variety of people. Therefore, ties to a wide variety of people who all have some of this information, enhances opportunity discovery (Johansson, 2000). Moreover, diversity of the people with whom one has ties increases the probability that one will get non-redundant information because people gain little new information in more homogeneous networks (Aldrich, 1999). Personal networks are important and necessary for entrepreneurial process (Dubini & Aldrich, 1991), yet little research exists on the role of social networks in opportunity identification. Most of the researchers on entrepreneurship process focus on what happens after the opportunity have been identified (Larson & Starr, 1993).

Researchers have reported that networking allows entrepreneurs to enlarge their knowledge of opportunities, gain access to critical resources, and to deal with business obstacles (Floyd & Wooldridge, 1999: Hills et al., 1997). Researchers on pre-venture activities are beginning to link entrepreneurial opportunity identification to the entrepreneur’s social network Hills et al., 1997) because social encounters between entrepreneurs and their network contacts have been found to be a source of new venture ideas (Christensen & Petersen, 1990). Reese & Aldrich, (1995) reported that networking allowed entrepreneurs to enlarge their span of action saved them time, and enabled them to gain access to resources and opportunities.

Weak ties represent casual acquaintances. Such weak ties possess the quality of not requiring the people to remain in contact with others for extended periods. For example, a friend of a professional acquaintance would represent a weak tie since there may not exist a continued relationship in that association. As another example, a potential entrepreneur may have a friend or small group of friends he knows very well. He may also have many casual acquaintances, each of whom also has a circle of close friends (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986). Strong ties refer to close friends and family members who can provide information and resources necessary for launching a new venture. Singh, (2000) noted that close proximity to the entrepreneur allows strong ties to provide more personal information that can be trusted and at low cost because the need to carry out follow-up research is minimised.

Networks with diverse resources help entrepreneurs to identify opportunities, find markets, and obtain legal identity and financial resources (Jarillo, 1989). Therefore, entrepreneurs with diverse networks tend to have a wider scope of opportunities open to them (Dubini & Aldrich, 1991). In this regard, researches have concluded that successful entrepreneurs use both weak and strong ties to obtain entrepreneurial ideas (DeKonning, 1999; Singh, 2000). ‘The use of networks as sources of entrepreneurial opportunity was also discussed by Monsted, (1993) who distinguished three types of networks, each serving a different function: a) network for entrepreneurial opportunities, b) network for service or product, that is, to solve a specific problem, and c) network for information and knowledge about whom to contact for a specific purpose. Monsted, (1993) added that the effectiveness of the network was highly dependent on trust. In the absence of trust is less frequent communication and consequently no cooperation.

Singh et al., (2000) reported that certain personal characteristics of entrepreneurs such as educational background, socio-economic status, and ethnic factors may improve opportunity recognition by enhancing one’s ability to build networks that are conducive to opportunity identification. In this regards, De Koning & Muzyka, (1999) concluded that good networks of weak ties are important for information gathering, while strong ties are crucial to resource assembly. Structural holes can be defined as the space between non-redundant contacts (Burt, 1992) within a network. Basing his reasoning on strong and weak ties, Burt (1992) explained that strong ties (close friend and relatives) allow people to know each other well, and expose them to redundant information. On the other hand, weak ties may remain anonymous to close friends, yet they are more likely to provide information which is not otherwise available. This is because of the friends’ circle which may gather information from various sources developed through the close friendship. On the other hand, weak ties would result in associating with only one person and when the connection with that single person is broken that situation would lead to losing the chances of garnering any new information (Singh, 2000). This made Burt (1992) to conclude that it is not the strength of the network ties that predicts access to unique information, but rather the “spaces” between networks.

Hills et al (1997) concluded that entrepreneurs with extended networks identify significantly more opportunities than entrepreneurs without networks (add in data for reference). This conclusion is consistent with Singh’s, (1998) findings that entrepreneurs with a wider network of social contacts identify more entrepreneurial opportunities that entrepreneurs with fewer contacts. Entrepreneurial activity does not occur in a vacuum but instead is embedded in cultural and social contexts (Singh, 1998). Although strong ties, constructed by close friends and associates, can provide trustworthy information for opportunity identification (Shane, 2003), weak ties (casual acquaintances) are equally important as sources of non-redundant information for identifying entrepreneurial opportunity (Granovetter, 1973). Strong ties cluster in particular groups while weak ties link members of different small groups. Diverse social ties can provide better access to information that facilitates opportunity identification (Aldrich & Zimmer, 1986).

Non-redundancy in social ties increases the likelihood that entrepreneurs will gain access to the right complement of information necessary for identifying opportunities (Shane, 2003). As a result, entrepreneurs with more diverse information sources are more likely to be successful Aldrich et al., 1987). In reviewing the existing literature, several studies have provided support for the arguments that social ties increase the likelihood of identifying entrepreneurial opportunities. Koller, (1988)surveyed 82 firm founders, and reported that 48 per cent had their business ideas suggested to them by business associates, relatives, or other social contacts. Hills, Lumpkin and Singh (1997) noted significant differences between solo and network entrepreneurs in that networked entrepreneurs identified significantly more opportunities than solo entrepreneurs. Singh et al., (1999) surveyed 256 founders of information technology consulting firms, and found that entrepreneurs with more diverse social ties tended to identify more opportunities than those with less diverse ties.

As shown by a body of literature, the concept of social networks is an important antecedent to opportunity identification. However, it should be noted that the use of social networks does not preclude other possible factors that have been found theoretically and empirically in relation to opportunity identification. Specifically, prior knowledge and cognitive properties (entrepreneurial alertness and creativity) are discussed in next sections. Singh et al., (1999) noted an entrepreneur’s personal social network has been called the “most significant resource of the firm”. Researchers have noted that social encounters between entrepreneurs and their network contacts are often a source of new venture ideas. Singh et al., (1999) sought to progress this by looking at the importance of entrepreneur’s social network characteristics, such as network size, weak ties and structural holes, to the opportunity recognition process. Their study found, using 256 information technology entrepreneurs, report that the size of network size and the presence of many weak ties in the social network of an entrepreneur showed a positive correlation with the volume of new ideas generated and opportunities recognised. It was correctly reported in the study that successful entrepreneurs used their social contacts to collect and perceive larger information which enabled them to recognize more number of opportunities that are feasible enlarging their “boundaries of rationality”. In support of Hills et al. (1997) they concurred with their findings that that network entrepreneurs identified significantly more opportunities than solo entrepreneurs, and were significantly less likely to go through a formal search for ideas. Further, they agreed that network entrepreneurs learned of more opportunities than solo entrepreneurs and were having better chances of recognizing more successful opportunities in the areas in which they had no prior knowledge or were not familiar with potentially due to their ability to reach more valuable information.

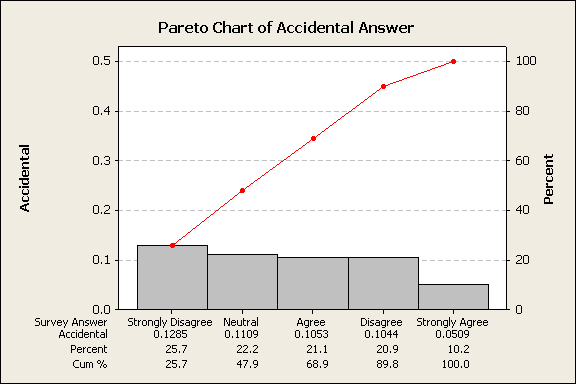

Accidental vs. purposeful search

Active search, in contrast to accidental search refers to active efforts to identify potential opportunities—untapped sources of potential profit (Hills & Shrader, 1998). Both of these factors have been found to be related to opportunity recognition, and affect may serve as a moderator of each (Baron, 2008). Fiet et al., (2004) found in a recent study that entrepreneurs who had started at least three successful ventures focused their searching on known information channels – channels that provided access to maximum possible sub-maximality for discovering a wealth creating venture idea. The proponents of viewing opportunity identification as a flash of insight argue that it is impossible to search systematically for unknown discoveries (Kaish & Gilad, 1991; Kirzner, 1997; Shane 2000; Shane & Venkataraman, 2000). As argued by Kirzner, (1997), an opportunity, by its very nature is not the subject of systematic search- what distinguishes discovery from successful search is that the former involves surprise. In an empirical study, Teach et al., (1989), found that only about half of the software presidents surveyed favoured systematic approaches to searching for opportunities, and firms that were founder on venture ideas (that were accidentally discovered and had not been subject to formal screening) achieved break even sales faster than those firms with more formal search and planning, and therefore concluded that strategic search and planning may not yield a better opportunity. Some empirical evidence however suggests that those who search information deliberately for any entrepreneurial opportunities are more likely to identify opportunities that people who do not. Gilad et al., (1989) surveyed 86 small business owners and 21 managers or small businesses, and found that entrepreneurs were more likely than managers to search for profit in a new deal. In another study Kaish & Gilad, (1991), the researchers compared 51 company founders with 36 executives in a large company and found that entrepreneurs were more likely to spend more time searching for information on their own through different information sources than executives. However Busenitz, (1996) replicated Kaish & Gilad, (1991) study using a random sample of entrepreneurs and managers from many different firms, but found little support for their empirical findings.

Creativity and Opportunity Recognition

Research supports the hypothesis that creativity, cognition and opportunity recognition are correlated. The first study by Wallas (1926) had a creativity model consisting of preparation, incubation, insight and evaluation. Elaboration was the fifth dimension added to this model. Hills Sharader and Lumpkin (1999) proved that recognition of business opportunities is more a context-specific form of creativity in entrepreneurship. Opportunity recognition is to be considered as a form of creativity.

Aims and Objectives

The entrepreneurial opportunity forms the base level of analysis for this study. An opportunity can be defined as a perceived situation where a good and/or a service can be introduced which the entrepreneur anticipates to result in a profit. Early methodological approaches have focused on improving the general understanding of the entrepreneurial process based upon anecdotal evidence of the psychological profile of the entrepreneur. Some of the traits examined by the literature include high ambition, drive, tolerance for uncertainty and risk orientation (Ardrich, 1990; Carsrud & Johnson, 1989; Hirish & Brush, 1986; Johnson, 1990). However methodological problems associated with these approaches have made them ineffective. Yet the need to better understand the factors influencing the entrepreneurship process continued to exist. Following the lead provided by the earlier researchers, other studies established a behavioral component, a belief component and an emotional component in the “entrepreneurial-attitude orientation” (Robinson et al., 1991). This study extends Robinson approach in identifying the different factors – behavioral, belief and emotional – that influence the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition amongst Irish start-up credit card companies. The results are expected to provide a better and more comprehensive understanding of the factors that have an impact on the opportunity recognition process. By restricting the study to entrepreneurs who focused on high-growth start-up companies, this study eliminates the observed differences experienced by other researchers who undertook the comparison of the attitudes and other factors influencing entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs belonging to different industries.

The research also extends to the role of personal contacts within the social networks of the opportunity recognition process. The study is expected to develop a conceptual discussion of entrepreneurial opportunities and provide empirical results based on mail survey responses from 42 entrepreneurs which detail the factors affecting their opportunity recognition decisions. The study provides a detailed discussion on the different elements of opportunity recognition which surround new venture idea identification with an emphasis on the implication of the findings for academic research, entrepreneurship education and business practice.

Identifying and presenting an analytical review on the factors influencing the entrepreneurship recognition process in the context of high growth start-up industries in Ireland is the central aim of this study.

Diverse objectives can be identified to be accomplished by the current study due to the exploratory nature of the study. Some of the objectives include (i) to test often proposed fundamental causes of entrepreneurial opportunities, (ii) to explore the concept of opportunity recognition as a deliberate process with many other related issues, (iii) to examine the relative importance of information sources for identification of major new opportunities, (iv) to examine the perceptions of the entrepreneurs about the role of market research in evaluating ideas and the criteria being used by them for such evaluation, (v) to assess the time factor in idea generation and opportunity recognition from the generated ideas.

For enabling a comprehensive presentation of the analysis this paper included theoretical review of the entrepreneur opportunity recognition process in general and the factors affecting the process which will enhance the theoretical knowledge and understanding of the reader on the concept of opportunity recognition. Therefore the theoretical study of the opportunity recognition process and the factors which have an impact on the process is one of the major objectives of the study. In the process of conducting the research the study also extends to a review of the available literature on the topic of opportunity recognition process. A review of the literature has enabled the formulation of the following research questions.

- Is opportunity identification related to the existence and use of social networks?

- Does prior knowledge of markets, products and customers problems increase the likelihood of opportunity identification?

- Does a high level of creativity and alertness lead to better opportunity identification?

- What are the other factors that have a significant influence on entrepreneurial opportunity identification?

- What is the time lag between the initial idea and the perception that it was an opportunity to start a new venture?

Research Methodology

The operational meaning of ‘entrepreneurship’ is to be construed as ‘starting a new business’ in its most generic approach. By definition any theory capable of integrating the many diverse elements of entrepreneurial research will have to be relatively abstract and general. Following this fundamental conceptualization this survey has been designed to be more abstract in nature. This is all the more reasonable in view of the fact that the entrepreneurship theory is the social science that views social processes from the perspectives of the element of change and improvisation in all human action. This study firmly believes in this conceptualization and the survey questionnaire has been formulated in accordance with this basic premise.

Sample

This research has used a quantitative survey method for collecting primary data. The initial sample included a selected group which fits into the group of having started business over the last 5 years and have grown the business to achieve sales of over €1million. The samples included in the group employ over 10 people. This grouping fit in under Enterprise Irelands category of High Potential Start-up (HPSU’s) criteria of manufacturing and export orientated product, or, offering a service that is internationally traded off a product or service that is innovative or technologically advanced; aiming to realise sales of €1million and employment of 10 or more within 3 years; and located and controlled in Ireland.

A list of 150 companies with company names, founder names, year of start up, email and phone numbers who have received funding form either Enterprise Ireland or the Irish Development Authority was complied as the prospective respondents of the survey. Through the personal contacts in both of these agencies based on his current assignment, the researcher obtained permission to use the contacts as a reference to help gain access to these companies to increase the likelihood of getting a completed survey response. Additionally to improve the response rate each of the contacts was followed by telephone calls in advance to provide prior notification of the survey, establishing their preference of e-mail or postal survey with a SAE if they prefer. Saunders et al indicate that this move by the researcher typically can result in expanding the response rate by 19%. However because of convenience the survey used ‘Survey Monkey’ available on Internet and no questionnaire was sent by post.

Analysis of the quantitative results has been conducted using the most appropriate techniques, in line with the recommendations made by Saunders et al. (2003) in Chapters 12 and 13 and Hair et al (2003) Chapters 11 to 15.

Data Collection Methods

The questionnaire was first pilot tested on a random subsample of 25 participants selected from the initial sample of150 respondents. The objective of the pilot testing was to refine the survey instruments for ensuring question accuracy and relevance of the questions. The pilot testing and revision of the survey instrument was considered essential in view of lack of a strong research stream for entrepreneurship in the industry context chosen for the study. The pretest evoked 6 responses which were used to better frame the questions in the survey and improve the quality of the instrument.

The low response rate from the pretest acted as an early indication of the potential difficulty in obtaining the primary data from the chosen sample. Other researchers have experienced similar difficulties in obtaining a large response rate in the entrepreneurial environment (Sapienza et al., 1988). In order to mitigate this issue of low response rate this study used the Dillman Total Design Approach (Dillman, 1991). Dillman’s technique involved a series of follow ups at regular intervals, in combination with specific formatting of the survey instrument and accompanying covering letters to potential respondents.

Once the format and content of the survey instrument was concluded, using ‘survey monkey’ the survey instrument in the form of questionnaire was sent by email. In the case of survey instruments sent by email, the respondents were sent the cover letter and the questionnaire with the request to send the responses to the email id of the researcher. The cover letter contained an explanation of the nature and purpose of the study, promise of anonymity of the respondent and offered a summary of the results for the return of the completed questionnaire. Confidentiality was ensured and a two-week return date was requested. Consent to participate was inferred from the completion of the survey. As recommended by Dillman (1991) a reminder was sent one week after the initial mailing of the questionnaire who has not responded as of the reminder date. Although recommended by Dillman another reminder was not sent due to time and resource constraints.

Survey Instrument

A questionnaire containing 22 open and close ended questions was prepared for use in the survey. It was considered important that the sample entrepreneurs were made to understand the difference between ideas and opportunities and for this purpose a simple opportunity recognition model developed for the understanding of the respondents with a brief explanation formed the initial part of the questionnaire. The respondents were requested to answer the questions based on the model and the brief discussion followed. Immediately following the model a validity check question on the understanding of the participants was inserted. Some of the questions in the survey questionnaire have resemblance to the survey questionnaire used by Singh, Hills and Lumpkin in their journal article New Venture Ideas and Entrepreneurial Opportunities: Understanding the Process of Opportunity Recognition.

Although the questionnaire was not segregated into different sections, questions were fitted in to form different sections dealing with different aspects of opportunity recognition process. The first set of questions was about the participants’ initial encounters in finding the new ideas about the setting up of their respective businesses. Second section is the most important one which seek to obtain information on the ways the respondents learned about the ideas. Next set of questions were set to get some information on the personal background of the participants such as the number of years experience the sample have in the industry, year of starting the firm, number of employees in the firm and the sector to which the respondent firm belongs. The penultimate question was on the personal traits of the individual respondents with respect to the identification of the idea as the opportunity for new venture. The final question in the questionnaire requested the respondents to provide suggestions as to how an entrepreneur should go about discovering/recognizing new business opportunities. The participants were requested to make suggestions in this respect based on their personal experience. The cover letter was made as brief as possible and it explained the purpose of the survey. In order to motivate the participants to send back the questionnaire and thereby improve the response rate, a lucky draw to win some books on management subject was offered and the cover letter contained the announcement of the draw. In respect of questions which required the personal view points of the respondents the questionnaire consisted choices of answers ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ exhibiting different intensities of the perceptions of the respondents.

Out of the initial selection of 150 sample entrepreneurs, questionnaires were sent to 137 companies which group formed the ‘entrepreneurs’ for the purpose of this survey. From the 137 questionnaires sent 42 of the respondents chose to return the filled out questionnaires. These replies formed the primary data collected under the survey. This provided a response rate of 30.6% which can be considered as a good response rate for any entrepreneurial survey undertaken. Study by Singh, Hill and Lumpkin evoked a response rate of 22% and the response rate for Chaganti & Parasuraman, (1996) was 12.3% and for Karagozoglu & Lindell, (1998) was 23%. As compared to the response rates in these previous surveys, the current study with a response rate of 30.6% is to be considered as favorable. Since the entire group of samples represented the high-growth industries no significant difference could be observed between the respondents and non-respondents in respect of the fundamental characteristics of the groups.

Findings

The respondents were introduced to the survey with a simple entrepreneurship opportunity recognition model based on the study by Singh, Hill and Lumpkin which was followed by two validity check questions on the understanding of the respondent entrepreneurs. On the first question 100 percent of the participants responded as to when someone first thinks of a possible new venture, but has not evaluated it much at all this survey would call it a “new venture idea”. Alternatively 92.85 percent (n=39) of the participants replied when someone has given a possible new venture some additional thought and/or evaluation, this survey would say it may lead to a “venture opportunity”. Two of the respondents were not clear on the question and could not answer the question. On the question of whether the respondents agree with the model presented as the basis of the questionnaire, 92.8 percent of the respondents have confirmed that they agree with the model. 4.7 percent of the participants were unable to decide on the utility of the model. Table 5.1 below shows the response received for this question.

Table 5.1 Agreement with the Opportunity Recognition Model

With 100 percent of the respondents answered the first question on “ideal” correctly and more than 90 percent of the respondents answered the second question on “opportunity” correctly it can be inferred that the entrepreneurs have clearly understood and agreed with the model. Further 92.8 percent of the participants have supported the model by agreeing to the model, with only 2.4 percent actually disagreed with the model. Only a small number of the participants have dissented with the model and therefore the validity of the model can be assumed to be strong.

Sources of Ideas

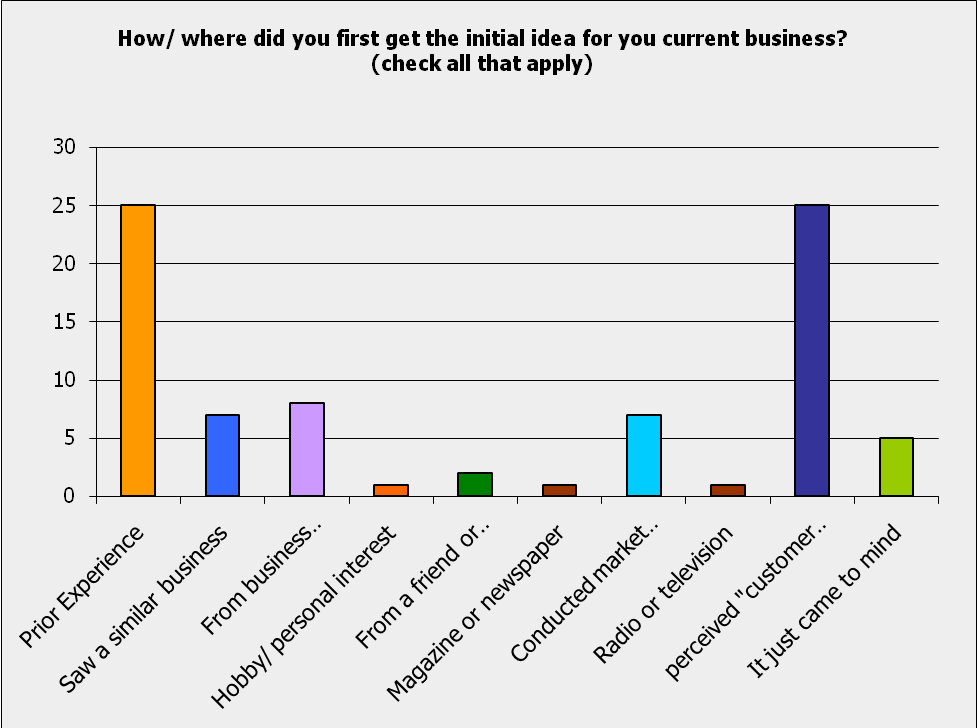

The next question on the questionnaire focuses on the source from which the entrepreneurs could get the initial ideas on the new ventures undertaken by them. Table 5.2 presents the results obtained for this question.

Table 5.2 Sources of Ideas

Survey results indicate prior experience and perceived customer needs are the highest used sources by the entrepreneurs for getting their ideas about the new ventures. This is consistent with the information on the number of years of experience of the entrepreneurs participated in the survey. There were more than 59 percent of the entrepreneurs who were having more than 10 years of experience in the industry before starring their new ventures as shown by the results of the survey. However social networks in the form of business associates have also contributed more new ideas to the entrepreneurs which could later be converted into opportunities. Seeing similar businesses and market researches conducted have also inspired the participants to get new ideas. This indicates that many of the entrepreneurs have based their new ventures based on models of the companies for which they worked. This may be so in the case of information technology firms in which the respondent entrepreneurs could have realized that they would be able to provide the same service to the client organizations as their employers provide. Four of the respondent entrepreneurs got their ideas from the universities and also based on the suggestions by the potential customers that it would be a good idea to venture into the present business. The results for this question are more or less consistent with the study by Singh et al., (2000) and Koller, (1988) where survey results indicated that more than 72 percent of the people survey reported that they got the ideas from prior experience and next to that from social networks and business associates.

Follow-up Activities of Entrepreneurs

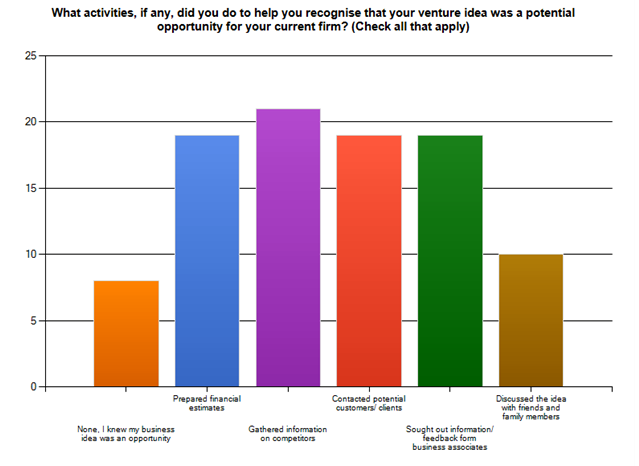

The entrepreneurs were requested to choose an answer on the type of activities if any undertaken by them that helped them recognizing the idea identified would turn into a potential opportunity for their current enterprise. The results are presented in the following table 5.3. In tune with the research model and the model of entrepreneurial opportunity, entrepreneurs usually undertake some follow up action to evaluate the chances of turning the ideas generated into opportunities for new ventures. Most of the entrepreneurs took part in the survey resorted to preparing the financial estimates (57.1 percent) as the next activity to further the idea into an opportunity. 54.8 percent of the respondents reported that they started gathering information on competitors. 40.5 percent of the respondents indicated that they sought information from their business associates. This result does not correspond with the previous study by Singh, Hill and Lumpkin where 52 percent of the participants reported that they consulted their business associates for further information/feedback on the ideas generated by them. 19.0 percent of the respondents answered differently in that they reported that they already knew that the idea was an opportunity. Perhaps these individuals did not possess enough prior experience than the other entrepreneurs nor did they run their firms successfully.

Table 5.3 Follow-up Activities of Entrepreneurs on Ideas Identified

Although these entrepreneurs may be perceived as more alert to opportunities and trusting their gut feelings, a definite view about their presumption of making their ventures successful could not be formed, unless further research is carried out in respect of this group of respondents on the running of their ventures. It may also be the case with the number of years of prior experience; certain entrepreneurs need not go through an evaluation process to convert their ideas into opportunities. There were other actions like preparing business and technical feasibility reports, undertaking market research, participating in online forums and entering into formal agreement with major clients indicated by the participants who were not included as choices options in the questionnaire for answering this question.

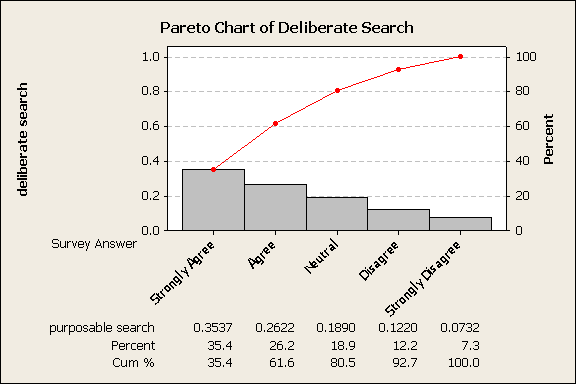

On the question of the way in which the entrepreneurs participated in the survey founded the firm 54.8 percent of the samples replied that they recognized an opportunity for their businesses and then started working towards bringing them into existence. On the other hand, 45.2 percent of the people first decided to start a business venture and then resorted to conducting a search for opportunities which ultimately led to the formation of the new business firms.

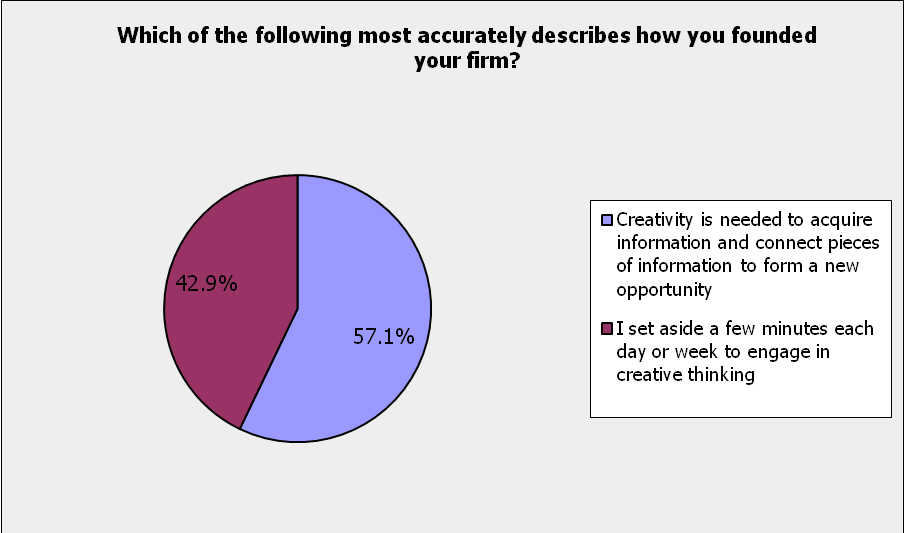

In 42.9 percent of the cases some amount of creativity is needed to acquire information and connect different pieces of information to form a new opportunity. Whereas, 57.1 percent of the people did a routine of setting aside a fixed amount of time each day or week to think further on the ideas and convert them into business opportunities.

Time Lag between Initial idea and Opportunity Recognition

Respondents were asked to indicate the approximate time that elapsed between the point at which they first identified the idea for their business venture and the actual time when they recognized the opportunity for their businesses.

Table 5.4 Time Lag between Initial idea and Opportunity Recognition

There was clarity among the respondents in identifying the time lag and there appears to be a wide distribution of time in this respect as shown in table 5.4. A majority of 71 percent of the participants have indicated that they have taken time in months and years before they could turn the ideas generated into real business opportunities. Only 19 percent of the respondents could convert the ideas into opportunities within weeks. None of them could easily turn the ideas into opportunities.

Time Lag between Opportunity Recognition and Founding the Business Firm

As theory indicates after an opportunity is recognized, entrepreneurs need some time before which they can actually form the business organization. Table 5.5 presents the results.

Almost 81 percent of the entrepreneurs took months or years for founding the firms from the opportunities recognized by them. Only 19 percent of the participants had the chance of converting the opportunities into real business ventures within shorter times of weeks.

Table 5.5 Time Lag between Opportunity Recognition and Founding the Business Firm

This result when combined with the time lag between the initial identification of the idea and opportunity recognition goes to prove that most of the entrepreneurs took time running between months and weeks between they initially identified the ideas and finally they converted such ideas into working firms.

Alterations in the Initial Venture Ideas

In the time between the idea is generated and converted into business opportunity, it might become necessary that initial idea or conceptualization of such idea is altered many times based on the market situation and other inputs from various sources. In order to evaluate the extent to which entrepreneurs had to alter their original ideas, the respondents were asked to report the changes made by them in their original ideas before it could be converted in to a business venture. Table 5.6 provides the results.

Table 5.6 Alterations in the Initial Venture Ideas

As a further extension to the question on the alterations in the initial venture ideas, the participants were asked to report on the number of people with whom they discussed the ideas to shape them into opportunities and later on into real business ventures. The results are reported in table 5.7.

Table 5.7 Number of People Discussed with

A majority of 45.2 percent of the people has discussed with 3 to 4 people before they could really shape the idea into opportunity and then on into business venture. The participants were also asked to indicate how much they changed their ideas to turn them into potential venture. The results are tabulated as below:

Table 5.8 Alterations made based on Discussions with Other People

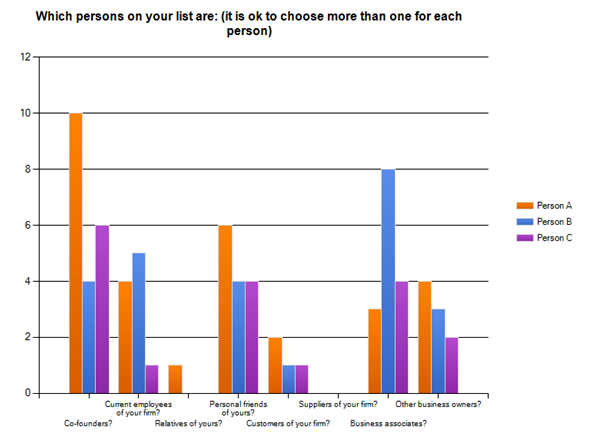

The respondents were also asked to indicate the person(s) whom had originally given them the idea which was later converted into a business opportunity. From the results it is observed that 100 percent of the respondents in the case of 11 respondents could get the idea or information on the idea from the first person they met or know. In respect of 9 respondents they had to discuss with second and third person before they could completely get the idea. Out of these people the knowledge of each person involved is reported as shown in the following table (Table 5.9).

Table 5.9 Interrelationship of Persons Discussed with by Entrepreneurs about the Idea

The participants were also asked to report the extent to which they personally know these individuals with whom they discussed the idea before the idea could be changed to opportunity.

The answers of the sample are presented in Table 5.10

Table 5.10 Personal Knowledge of the People with whom Ideas were discussed

Relationship with Entrepreneur of the People who Provided the Idea

In order to evaluate the relationship of the person who originally provided the idea to the entrepreneur, the respondents were asked to report on the relationship the entrepreneur holds with such person after the business venture came into existence.

Table 5.11 Current Relationship with Entrepreneur

The relationship was expected to fall in the categories of co-founder, relative, current employee, customer or supplier of the firm, or other business associates. The responses of the sample are shown in table 5.11 and in he the figure for easy comparison.

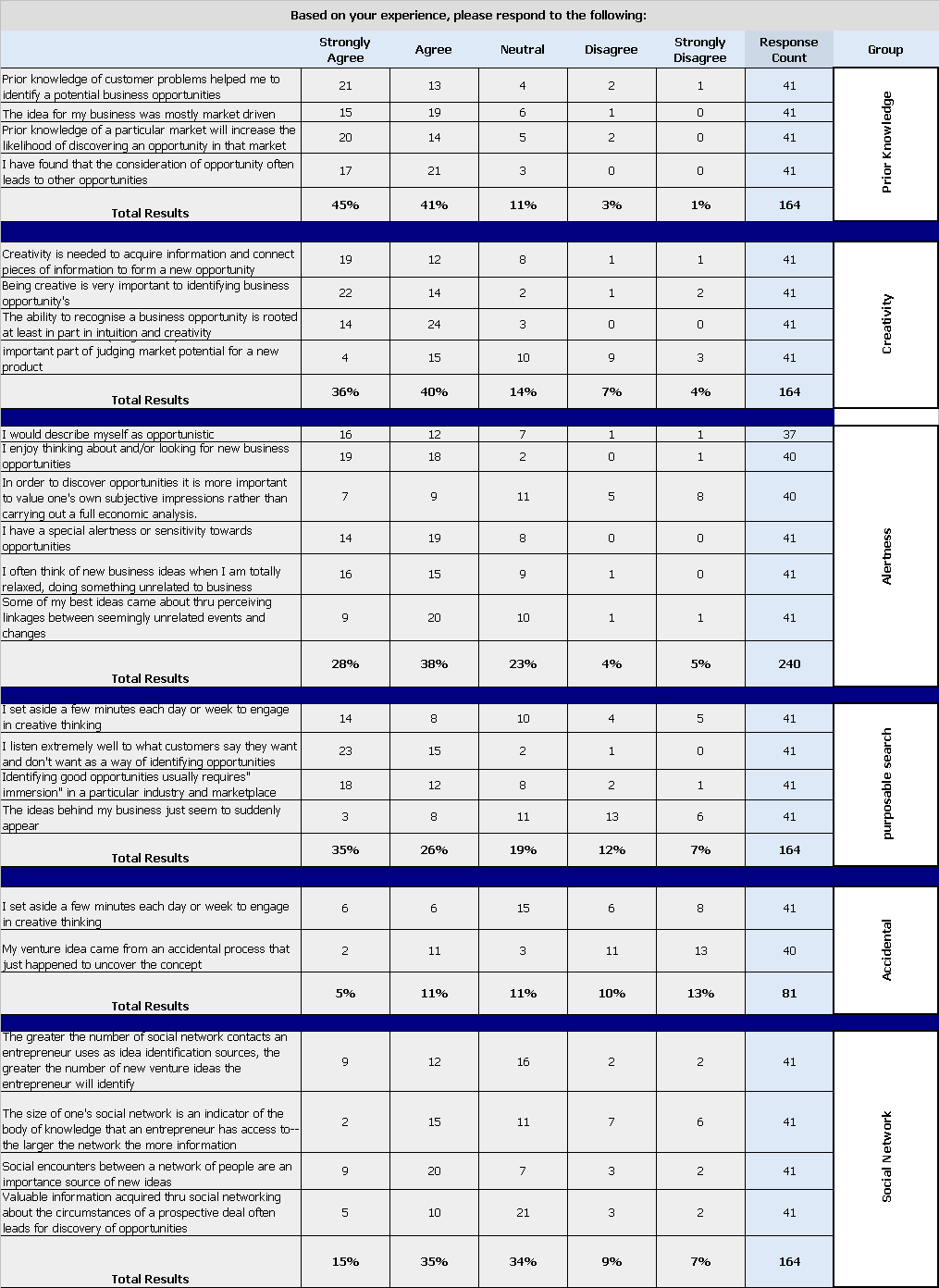

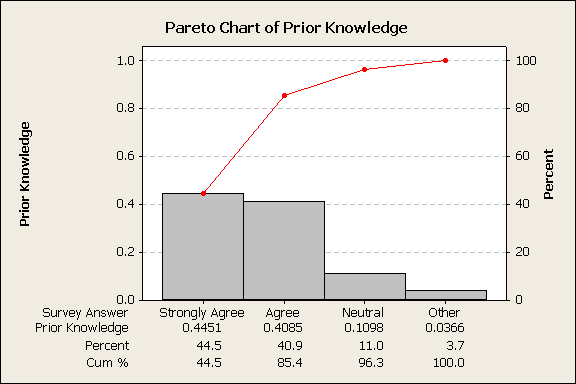

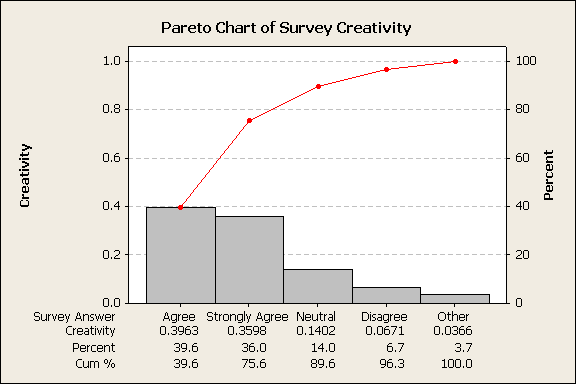

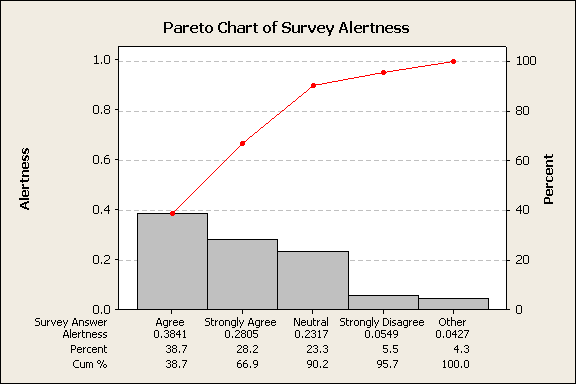

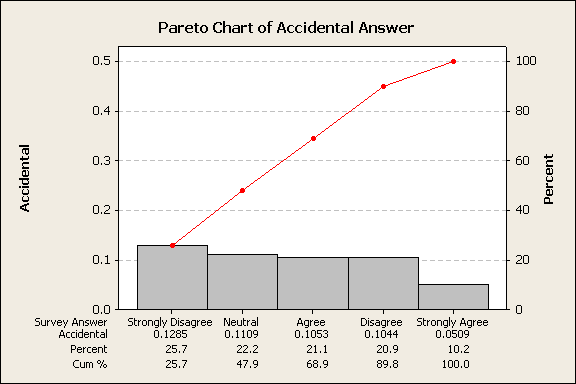

Attitudes and Factors Contributing to Identifying Ideas and Recognizing Opportunities

Based on the individual perceptions and experiences, the respondents were asked to choose the attitude/factor that contributes most to identifying the ideas and later on changing them into opportunities. The answers given by the respondents are tabulated as below (Table 5.12)

Table 5.12 Attitudes and Factors Contributing to Identifying Ideas and Recognizing Opportunities

The answers were choices from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. By assigning the values from 5 to 1 respectively for the choices, the number of respondents for each choice is weighted and the mean value arrived at for a better understanding of the responses received from the participants.

Demographic Information

Question number 16 to Question number 20 required the participants to convey some basic demographic information about the respondents and their organizations such as number of years of experience the entrepreneur has, the year the entrepreneur started the firm, educational level of the entrepreneurs, number of current employees of the firm, sector/industry to which the respondent’s firm belongs. The answers given by the respondents are presented in the following tables which are self explanatory about the contents they represent.

Table 5.13 Number of Years of Experience of the Participants

Table 5.14 Educational Level of the Participants

Table 5.15 Years in which the Participant Started the Firm

Table 5.16 Number of Current Employees in the Participants’ Firms

Table 5.17 Sector/Industry to which Participants’ Firms Belong

Personal Opinion of Respondents on the Factor Contributing to Opportunity Recognition

Through another question the respondents were asked to identify the most important factor that might contribute best for the idea generation and opportunity recognition. The mean values for the answers given by the respondents are tabulated and presented (Table 5.18)

Table 5.18 Personal Opinion of Respondents on the Factor Contributing to Opportunity Recognition

Combined responses for strongly agree & agree, show 85% of respondents either strongly agree or agree with the importance of prior knowledge in relation to the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities, i.e. very strong support for this variable, on the other hand only 16% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the importance of social networks in relation to the discovery of entrepreneurial opportunities, therefore very weak support for this, this contrast sharply from Singh studies.

The last question of the questionnaire requested the respondents to comment based on their personal experience on the ways an entrepreneur should go about discovering/recognizing new business opportunities. The responses received are varied in nature. For instance, one of the respondents remarked

In my experience there are so many business ideas, the key question is how you effectively dismiss 99% of them before you spend real time trying to evaluate. In orders word being able to very effectively and efficient judge if an idea merits further investigation is a critical skill. It is also critical to be able to recognize that an idea may have merit but just not have merit for you or your organization. If done well, this allows you to focus on the ideas that may have legs. Also it is vital not to initially discuss ideas with negative people. The last thing a new idea need is a person who says ‘Just to be devil’s advocate’. New ideas need pure enthusiasm to tease out potential. It is only in when determining if the idea is fleshed out should it be challenged.

The opinions and suggestions in this respect are analyzed in the next chapter dealing with the discussion on the findings of the survey.

Discussion and Conclusions

The objective of this study was to examine the factors that influence the entrepreneurial opportunity identification process. More specifically the factors that have been found in the literature such as social networks, prior knowledge, alertness, and creativity were examined for their respective influence and contribution to the entrepreneurial opportunity recognition process. The contributions of this study based upon the findings of the survey will be discussed in this chapter followed by some concluding remarks.

Characteristics of the Participants

From the demographic information provided by the respondents, it can be observed that about 85 percent of the participants are graduates and post graduates which enhances the reliability of the study. The fact that about 60 percent of the respondents have more than 10 years of experience in their respective industries also contributes to the reliability of the findings. However, a majority of the firms have been started in the year 2007 and a majority of the firms employ only less than 10 employees currently. The entrepreneurs of these small firms can be considered as more suitable as sample to represent the population of high-growth firm as most of these firms belong to software industry (54.8 percent).

Key Findings of the Study